Ayutthaya Kingdom

The Ayutthaya Kingdom (/ɑːˈjuːtəjə/; Thai: อยุธยา, RTGS: Ayutthaya, IAST: Ayudhyā or Ayodhyā, pronounced [ʔā.jút.tʰā.jāː] (![]() listen)) was a Siamese kingdom that existed in Southeast Asia from 1351[1] to 1767, centered around the city of Ayutthaya, in Siam, or present-day Thailand. The Ayutthaya Kingdom is considered to be the precursor of modern Thailand and its developments are an important part of the History of Thailand.

listen)) was a Siamese kingdom that existed in Southeast Asia from 1351[1] to 1767, centered around the city of Ayutthaya, in Siam, or present-day Thailand. The Ayutthaya Kingdom is considered to be the precursor of modern Thailand and its developments are an important part of the History of Thailand.

Ayutthaya Kingdom อาณาจักรอยุธยา Anachak Ayutthaya | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1351[1]–1767 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Trade flag (1680–1767)

_goldStamp_bgred.png.webp) Seal (1657–1688)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Ayutthaya Kingdom and Mainland Southeast Asia in c. 1540. Note: Southeast Asian political borders remained relatively undefined until the modern period. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

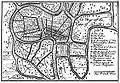

c. 1686–89 French map of the Ayutthaya Kingdom (Siam) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Majority: Theravada Buddhism Minority: Hinduism, Roman Catholic, Islam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy with Chatusadom as executive body; mercantile absolutism[14][15] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notable rulers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1351–1369 | Ramathibodi I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1448–c. 1488[2] | Borommatrailokkanat | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1590–1605 | Naresuan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prasat Thong | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1657–1688 | Narai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1733–1758 | Borommakot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1758 | Uthumphon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1758–1767 | Ekkathat | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | None | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Founding of Ayutthaya | 4 March 1351[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Personal union with Sukhothai Kingdom | 1438 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Vassal of Taungoo Dynasty | 1564–1569 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Merge with Sukhothai, and independence from Taungoo | 1583–1584 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Naresuan and Mingyi Swa's Elephant War | 1593 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• End of Sukhothai Dynasty | 1629[16][17] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• End of Prasat Thong Dynasty | 11 July 1688 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Dissolution | 7 April 1767 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 1600[18] | ~2,500,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Pod Duang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Thailand |

|---|

|

|

|

The Ayutthaya Kingdom emerged from the mandala of city-states on the Lower Chao Phraya Valley in the late fourteenth century during the decline of the Khmer Empire. After a century of territorial expansions, Ayutthaya became centralized and rose as a major power in Southeast Asia. Ayutthaya faced invasions from the Toungoo dynasty of Burma, starting a centuries' old rivalry between the two regional powers, resulting in the First Fall of Ayutthaya in 1569. However, Naresuan (r. 1590–1605) freed Ayutthaya from brief Burmese rule and expanded Ayutthaya militarily. By 1600, the kingdom's vassals included some city-states in the Malay Peninsula, Sukhothai, Lan Na and parts of Burma and Cambodia,[19] although the extent of Ayutthaya's control over its neighbors varied over time. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Ayutthaya emerged as an entrepôt of international trade and its cultures flourished. The reign of Narai (r. 1657–1688) was known for historic contact between the Siamese court and Europeans, most notably the 1686 Siamese diplomatic mission to the court of King Louis XIV of France. The Late Ayutthaya Period was described as a "golden age" of Siamese culture and saw the rise in predominance of trade and political and cultural influence from the Chinese trade,[20] a development that would continue to expand for the next century following the fall of Ayutthaya.[21][22]

In the eighteenth century, a series of socio-economic and political pressures within the kingdom, prominent among them sequential succession conflicts due to the nature of the Ayutthaya succession system, left Ayutthaya militarily weakened and thus unable to effectively deal with a renewed series of Burmese invasions, in 1759–60 and 1765–67, from the new and vigorous and expansionistic Konbaung dynasty of Burma, determined to acquire its growing wealth and eliminate their long-time regional rivals.[21] In April 1767, after a 14-month siege, the city of Ayutthaya fell to besieging Burmese forces and was completely destroyed, thereby ending the 417-year-old Ayutthaya Kingdom. Siam, however, quickly recovered from the collapse and the seat of Siamese authority was moved to Thonburi, and later Bangkok, within the next 15 years.

In foreign accounts, Ayutthaya was called "Siam", but many sources say the people of Ayutthaya called themselves Tai, and their kingdom Krung Tai (Thai: กรุงไท) meaning 'Tai country' (กรุงไท). It was also referred to as Iudea in a painting requested by the Dutch East India Company.[note 1]

History

Origins

The origin of Ayutthaya had been subjected to scholarly debates. Traditional accounts hold that King Uthong, the ruler of a city called "Uthong", moved his court due to the threat of an epidemic.[23] The city of "Uthong" was not the modern U Thong District, Suphan Buri Province, which was a major Dvaravati site but had already been abandoned before the foundation of Ayutthaya. Van Vliet's chronicles, a seventeenth-century work, stated that King Uthong was a Chinese merchant who established himself at Phetchaburi before moving to Ayutthaya. Tamnan Mulla Satsana, a sixteenth-century Lanna literature, stated that King Uthong was from Lavo Kingdom. Regardless of his origin, King Uthong, who had been a post-Angkorian ruler of one of the cities in Lower Chao Phraya Valley, moved his court to an island on intersection of three rivers; Chao Phraya River, Lopburi River and Pa Sak River, and founded Ayutthaya there in 1351, naming it after Ayodhya, one of the holiest Hindu cities of India of the same name.

The city of Ayutthaya itself, however, might have existed before the supposed "foundation" in 1351. Some temples in Ayutthaya have been known to exist before 1351. Recent archaeological works reveal pre-existing barays superimposed on by subsequent structures and support the Lavo theory. The barays later became Bueng Phra Ram (Thai: บึงพระราม) in the place called Nong Sano (Thai: หนองโสน), in which King Uthong had laid his foundation. Excavation map shows the traces from a baray close to the southwestern tip of Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon which could have been built on a former important Angkorian temple complex.[24] Lavo (modern Lopburi) had been the center of Angkorian political and cultural influence in Central Thailand. The Lavo kingdom had established[25] the port on the site of Ayutthaya called Ayodhaya Sri Rama Thepnakorn (Thai: อโยธยาศรีรามเทพนคร).[26] King Uthong established his base on the pre-existing Angkorian site.[27][28]

Many polities had existed in the Lower Chao Phraya Valley before the foundation of Ayutthaya including the Khmer Empire, Lopburi, Suphan Buri and Phetchaburi. Suphanburi had sent a tribute mission to Song dynasty in 1180 and Petchaburi to the Yuan dynasty in 1294. Some argue that Suphanburi was, in fact, Xiān[29] mentioned in Chinese sources.

Early expansion and wars

_of_Wat_Phra_Si_Sanphet.jpg.webp)

The integrity of the patchwork of cities of early Ayutthaya Kingdom was maintained largely through familial connections under the mandala system.[30] King Uthong had his son, Prince Ramesuan, the ruler of Lopburi (Lavo), his brother, the ruler of Praek Sriracha[31](in modern Chainat Province) and his brother-in-law, Khun Luang Pa-ngua, the ruler of Suphanburi. The ruler of Phetchaburi was his distant relative.[32] The king would appoint a prince or a relative to be the ruler of a city, and a city that was ruled by a prince was called Muang Look Luang (Thai: เมืองลูกหลวง). Each city ruler swore allegiance and loyalty to the King of Ayutthaya but also retained certain privileges.

Politics of Early Ayutthaya was characterized by rivalries between the two dynasties; the Uthong dynasty based on Lopburi and the Suphannabhum dynasty based on Suphanburi. When King Uthong died in 1369, he was succeeded by his son Ramesuan. However, Khun Luang Pa-Ngua, the ruler of Suphanburi, marched and usurped the throne from Ramesuan in 1370, prompting Ramesuan to return to Lopburi. Khun Luang Pa-Ngua crowned himself as King Borommaracha I and with his death in 1388 was succeeded by his son Thong Lan. However, Ramesuan then marched from Lopburi to seize Ayutthaya and had Thong Lan executed. Ramesuan was crowned king once more and was eventually succeeded by his son Ramracha at his death in 1395. Prince Intharacha, who was King Borommaracha's nephew, usurped the throne from Ramracha in 1408. Uthong dynasty was then purged and became a mere noble family of Ayutthaya until the 16th century.

Ayutthaya sent military campaigns into Sukhothai,[33]: 222 Angkor, and Lan Na. Victory of King Borommaracha I over Sukhothai, whose capital was now at Phitsanulok, in 1378 put Sukhothai under the dominance of Ayutthaya. Borommaracha II led armies to attack Angkor in 1431 (forcing the Cambodians to move their capital from Angkor to Phnom Penh),[34] and also expanded into the Korat Plateau. Borommaracha II made his son Prince Ramesuan the ruler of Sukhothai at Phitsanulok. Upon his death in 1448, Prince Ramesuan took the throne of Ayutthaya as King Borommatrailokkanat, also known as "Trailokkanat", thus Ayutthaya and Sukhothai was united. The Ligor Chronicles composed in the seventeenth century said that the ruler of Petchaburi had sent his son to rule Ligor in Southern Thailand. Ligor Kingdom was then incorporated into Ayutthaya.

An alternate viewpoint of this period of Ayutthaya, promoted by Baker and Phongpaichit, challenged the traditional narrative of Ayutthaya's glorious conquests over Sukhothai and Angkor, arguing that this period, while still involved Ayutthaya military expeditions into other countries, did so alongside peaceful policies, as evident with the intermarrying of royal dynasties between the Suphannabhum (Ayutthaya) and Sukhothai dynasties over generations that ensured Sukhothai's gradual political merger into Ayutthaya and the back and forth cultural influences shared between Ayutthaya and Angkor.[35]

Centralization and institutionalization

Ayutthaya had acquired two mandalas; Sukhothai and Ligor. The Muang Look Luang system was inadequate to govern relatively vast territories. The government of Ayutthaya was centralized and institutionalized under King Trailokkanat in his reforms promulgating in Palatine Law of 1455, which became the constitution of Ayutthaya for the rest of its existence and continued to be the constitution of Siam until 1892, albeit in altered forms. The central government was dominated by the Chatusadom system (Thai: จตุสดมภ์ lit. "Four Pillars), in which the court was led by two Prime Ministers; the Samuha Nayok the Civil Prime Minister and the Samuha Kalahom the Grand Commander of Forces overseeing Civil and Military affairs, respectively. Under the Samuha Nayok were the Four Ministries. In the regions, the king sent not "rulers" but "governors" to govern cities. The cities were under governors who were from nobility not rulers with privileges as it had previously been. The "Hierarchy of Cities" was established and cities were organized into four levels. Large, top level cities held authorities over secondary or low-level cities.

The emerging Kingdom of Ayutthaya was also growing powerful. Relations between Ayutthaya and Lan Na had worsened since the Ayutthayan support of Thau Choi's rebellion in 1451, Yuttitthira, a noble of the Kingdom of Sukhothai who had conflicts with Trailokkanat of Ayutthaya, gave himself to Tilokaraj. Yuttitthira urged Trailokkanat to invade Phitsanulok, igniting the Ayutthaya-Lan Na War over the Upper Chao Phraya valley (the Kingdom of Sukhothai). In 1460, the governor of Chaliang surrendered to Tilokaraj. Trailokkanat then used a new strategy and concentrated on the wars with Lan Na by moving the capital to Phitsanulok. Lan Na suffered setbacks and Tilokaraj eventually sued for peace in 1475.

Due to the lack of succession law and a strong concept of meritocracy, whenever the succession was in dispute, princely governors or powerful dignitaries claiming their merit gathered their forces and moved on the capital to press their claims, culminating in several bloody coups.[36]

At the start of the 15th century, Ayutthaya showed an interest in the Malay Peninsula, but the great trading ports of the Malacca Sultanate contested its claims to sovereignty. Ayutthaya launched several abortive conquests against Malacca which was diplomatically and economically fortified by the military support of Ming China. In the early-15th century the Ming admiral Zheng He established a base of operation in the port city, making it a strategic position the Chinese could not afford to lose to the Siamese. Under this protection, Malacca flourished, becoming one of Ayutthaya's great foes until the capture of Malacca by the Portuguese.[37]

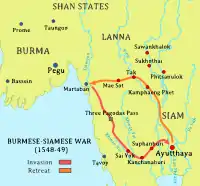

First Burmese wars

Starting in the middle of the 16th century, the kingdom came under repeated attacks by the Taungoo Dynasty of Burma. The Burmese–Siamese War (1547–49) resulted in a failed Burmese siege of Ayutthaya. A second siege (1563–64) led by King Bayinnaung forced King Maha Chakkraphat to surrender in 1564. The royal family was taken to Pegu (Bago), with the king's second son Mahinthrathirat installed as the vassal king.[38]: 111 [39]: 167–170 In 1568, Mahinthrathirat revolted when his father managed to return from Pegu as a Buddhist monk. The ensuing third siege captured Ayutthaya in 1569 and Bayinnaung made Mahathammarachathirat (also known as Sanphet I) his vassal king, instating the Sukhothai dynasty.[39]: 167

In May 1584, less than three years after Bayinnaung's death, Uparaja Naresuan (or Sanphet II), the son of Sanphet I, proclaimed Ayutthaya's independence. This proclamation resulted in repeated invasions of Ayutthaya by Burma which the Siamese fought off ultimately finishing in an elephant duel between King Naresuan and Burmese heir-apparent Mingyi Swa in 1593 during the fourth siege of Ayutthaya in which Naresuan famously slew Mingyi Swa.[40]: 443 Today, this Siamese victory is observed annually on 18 January as Royal Thai Armed Forces day. Later that same year warfare erupted again (the Burmese–Siamese War (1593–1600)) when the Siamese invaded Burma, first occupying the Tanintharyi province in southeast Burma in 1593 and later the cities of Moulmein and Martaban in 1594. In 1599, the Siamese attacked the city of Pegu but were ultimately driven out by Burmese rebels who had assassinated Burmese King Nanda Bayin and taken power.[40]: 443

In 1613, after King Anaukpetlun reunited Burma and took control, the Burmese invaded the Siamese-held territories in Tanintharyi province, and took Tavoy. In 1614, the Burmese invaded Lan Na which at that time was a vassal of Ayutthaya. Fighting between the Burmese and Siamese continued until 1618 when a treaty ended the conflict. At that time, Burma had gained control of Lan Na and while Ayutthaya retained control of southern Tanintharyi (south of Tavoy).[38]: 127–130 [40]: 443

Foreign influence and dynastic struggles

In 1605, Naresuan died of illness while on campaign against a Burmese spillover conflict in the Shan region, leaving a greatly expanded Siamese kingdom to be ruled by his younger brother, Ekathotsarot (Sanphet III).[41]: 173–180 Ekathotsarot's reign was marked with stability for Siam and its sphere of influence, as well as increased foreign interactions, especially with the Dutch Republic, Portuguese Empire, and Tokugawa Shogunate (by way of the Red Seal Ships), among others. Indeed, representatives from many foreign lands began to fill Siam's civil and military administration - Japanese traders and mercenaries led by Yamada Nagamasa, for example, had considerable influence with the king.[42]: 51

Ekathotsarot's era ended with his death in 1610/11.[43] The question of his succession was complicated by the alleged suicide of his eldest legitimate son, Suthat, while his second legitimate son, Si Saowaphak, was never legally designated as an heir by Enkathotsarot himself. Nonetheless, Si Saowphak succeeded to the throne against his late father's wishes, and led a short and ineffective reign in which he was kidnapped and held hostage by Japanese merchants, and later murdered.[41]: 203–206 After this episode, the kingdom was handed to Songtham, a lesser son born of Enkatotsarot and a first-class concubine.

Songtham temporarily restored stability to Ayutthaya and focused inward on religious construction projects, notably a great temple at Wat Phra Phutthabat. In the sphere of foreign policy, Songtham lost suzerainty of Lan Na, Cambodia and Tavoy[41]: 207–208 , expelled the Portuguese,[44] and expanded Siam's foreign trade ties to include both the English East India Company and French East India Company, along with new merchant colonies in Siam representing communities from all across Asia.[42]: 53–54, 56 Additionally, Songtham maintained the service of Yamada Nagamasa, whose Japanese mercenaries were at this point serving as the king's own royal guard.[41]

As Songtham's life began to fade, the issue of succession generated conflict once again when both King Songtham's brother, Prince Sisin, and his son, Prince Chetthathirat, found support for their claims among the Siamese court. Although Thai tradition typically favored brothers over sons in matters of inheritance, Songtham enlisted the help of his influential cousin, Prasat Thong to ensure his son would inherit the kingdom instead. When Songtham died in 1628, Prasat Thong used his alliance with Yamada Nagamasa's mercenaries to purge everyone who had supported Prince Sisin's claim, eventually capturing and executing Sisin as well.[41]: 213 Soon Prasat Thong became more powerful in Siam than the newly-crowned King Chetthathriat, and through further intrigue staged a coup in which Chetthathirat was deposed and executed in favor of his even younger brother Athittayawong, whom Prasat Thong intended to use as a puppet ruler.[41]: 215–216

This form of government was quickly met with resistance by elements within the Thai court who were dissatisfied with the idea of having two acting heads of state. Since Prasat Thong already ruled Siam in all but name as Kalahom, he opted to resolve the issue by orchestrating the final dethronement and execution of the child king in 1629. Thus, Prasat Thong had completely usurped the kingdom by double (perhaps triple) regicide, extinguishing the Sukhothai dynasty 60 years after its installation by the Burmese.[41]: 216 Many of King Prasat Thong's former allies abandoned his cause following his ascension to the throne. In the course of quelling such resistance, Prasat Thong assassinated his former ally Yamada Nagamasa in 1630 (who now opposed Prasat Thong's coup), and promptly banished all the remaining Japanese from Siam.[42] While a community of Japanese exiles were eventually welcomed back into the country, this event marks the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate's long-standing formal relationship with the Ayutthaya Kingdom.[42]

Narai the Great and revolution

Upon his death in 1656, King Prasat Thong was succeeded first by his eldest son, Chai, who was almost immediately deposed and executed by the late King's brother, Si Suthammaracha, who in turn was defeated in single combat by his own nephew, Narai.[41]: 216–217 Narai finally assumed a stable position as King of Ayutthaya with the support of a mainly foreign court faction consisting of groups that had been marginalized during the reign of his father, Prasat Thong. Among his benefactors were, notably, Persian, Dutch, and Japanese mercenaries.[41] It should therefore come as no surprise that the era of King Narai was one of an extroverted Siam. Foreign trade brought Ayutthaya not only luxury items but also new arms and weapons. In the mid-17th century, during King Narai's reign, Ayutthaya became very prosperous.[45]

In 1662 war between Burma and Ayutthaya (the Burmese-Siamese War (1662-64)) erupted again when King Narai attempted to take advantage of unrest in Burma to seize control of Lan Na.[46]: 220–227 Fighting along the border between the two adversaries continued for two years and at one time Narai seized Tavoy and Martaban. Ultimately, Narai and the Siamese ran out of supplies and returned home back within their border.[38]: 139 [40]: 443–444

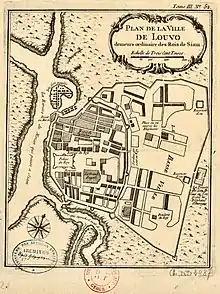

While commercially thriving, Narai's reign was also socially tumultuous. Much of this can be attributed to three-way conflict between the Dutch, French, and English trading companies now operating in Siam at an unprecedented intensity due to Siam's role as a center of trade, fostered by Narai. Of these competing foreign influences, Narai tended to favor relations with the French, wary of the growing Dutch and English colonial possessions in the South China Sea.[42]: 58 Soon, Narai began to welcome communities of French Jesuits into his court, and pursue closer relations with both France and the Vatican.[41]: 243–244 Indeed, the many diplomatic missions conducted by Narai to such far-flung lands are some of the most celebrated accomplishments of his reign. Narai as well leased the ports of Bangkok and Mergui to the French, and had many French generals incorporated into his army to train it in Western strategy and supervise the construction of European-style forts.[47] During this time, Narai abandoned the traditional capital of Ayutthaya for a new Jesuit-designed palace in Lopburi.[41]: 250–251

As a growing Catholic presence cemented itself in Siam, and an unprecedented number of French forts were erected and garrisoned on land leased by Narai, a faction of native Siamese courtiers, Buddhist clergy, and other non-Catholic and/or non-French elements of Narai's court began to resent the favorable treatment French interests received under his reign.[42]: 63 This hostile attitude was especially directed at Constantine Phaulkon, a Catholic Greek adventurer and proponent of French influence who had climbed to the rank of Narai's Prime Minister and chief advisor of foreign affairs.[48] Much of this turmoil was primarily religious, as the French Jesuits were openly attempting to convert Narai and the royal family to Catholicism.[42]: 62

Narai was courted not just by Catholic conversion, but as well by proselytizing Muslim Persians, Chams and Makassars in his court, the later of which communities launched an unsuccessful revolt in 1686 to replace Narai with a Muslim puppet king.[49] While members of the anti-foreign court faction were primarily concerned with Catholic influence, there is evidence to suggest that Narai was equally interested in Islam, and had no desire to fully convert to either religion.[50]

Nonetheless, a dissatisfied faction now led by Narai's celebrated Elephantry commander, Phetracha, had long planned a coup to remove Narai. When the king became seriously ill in May of 1688, Phetracha and his accomplices had him arrested along with Phaulkon and many members of the royal family, all of whom were put to death besides Narai, who died in captivity in July of that year.[41] : 271–273 [51]: 46, 184 . With the king and his heirs out of the way, Phetrachathen usurped the throne and officially crowned himself King of Ayutthaya on August 1.[51] : 184

King Phetracha took Mergui back from French control almost immediately, and began the pivotal Siege of Bangkok, which culminated in an official French retreat from Siam. Pretacha's reign, however, was not stable. Many of Phetracha's provincial governors refused to recognize his rule as legitimate, and rebellions by the late Narai's supporters persisted for many years.[41]: 276–277 The most important change to Siam in the aftermath of the revolution was Phetracha's refusal to continue Narai's foreign embassies. King Phetracha opted instead to reverse much of Narai's decisions and closed Thailand to almost all forms of european interaction except with the Dutch.[41]: 273–276

Golden age of culture

.png.webp)

After a bloody period of dynastic struggle, Ayutthaya entered into what has been called a golden age, a relatively peaceful episode in the second quarter of the 18th century when art, literature, and learning flourished, most prominently during the reign of King Borommakot (r. 1733-1758). Ayutthaya wat architecture reached its high point in the late 17th-18th centuries, the construction and renovation of temples in this period completely transformed Ayutthaya's skyline (much of the surviving buildings in Ayutthaya were built or renovated during Borommakot's reign).[52][53] Siamese wat murals started becoming elaborate.[54] In 1753, following the request made by a delegation of Sri Lankan monks who traveled to Ayutthaya, Borommakot sent two Siamese monks to reform Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

Prosperity, growth of Chinese trade and influence in Siam

Despite the departure of most Europeans from Ayutthaya, their economic presence in Ayutthaya was negligible in comparison to the Ayutthaya China-Indian Ocean trade. Lieberman, later reinforced by Baker and Phongpaichit, refutes the idea that Siam's alleged isolationism from global trade following the French and English departure in 1688 led to Ayutthaya's gradual decline leading up to its destruction by the Burmese in 1767, stating:

Clearly, however, the late 1600s and especially the early 1700s inaugurated a period not of sustained decline, but of Chinese-assisted economic vitality that would continue into the 19th century.[55][56][57]

Instead, the 18th century was arguably the Ayutthaya Kingdom's most prosperous,[58] particularly due to trade with Qing China. The growth of China's population in the late 17th-18th centuries, alongside nationwide rice shortages and famines in Southern China, meant that China was eager to import rice from other nations, particularly from Ayutthaya. During the Late Ayutthaya Period (1688–1767), the Chinese population in Ayutthaya possibly tripled in size to 30,000 from 1680 to 1767, whose population in the capital even exceeded that of the Siamese. The Chinese played a pivotal role in stimulating Ayutthaya's economy in the last 100 years of the kingdom's existence and eventually played a pivotal role in Siam's quick recovery from the Burmese invasions of the 1760s,[59][60] whose post-Ayutthaya monarchs (Taksin and Rama I), held close ties, through blood and through political connections, to this Sino-Siamese community.[61]

Succession conflicts and instability

The last fifty years of the kingdom witnessed a bloody struggle among the princes. The throne was their prime target. Purges of court officials and able generals followed. The last monarch, Ekkathat, originally known as Prince Anurakmontree, forced the king, who was his younger brother, to step down and took the throne himself.[62]: 203

Corruption was rampant due to economic prosperity. People fled into the countryside, as well as through a variety of other ways, in order to flee corvee conscription.

Second Burmese wars and the resumption of warfare

_map_-_EN_-_001.jpg.webp)

There were minor foreign wars, in the absence of major wars that occurred in the 16th and late 18th-early 19th centuries. Ayutthaya fought with the Nguyễn Lords (Vietnamese rulers of south Vietnam) for control of Cambodia starting around 1715. But a greater threat came from Burma, where the new Konbaung dynasty had reunified Burma and was embarking on a series of campaigns of conquests and subjugations outside of Burma.[63]

The Burmese–Siamese War (1759–1760) begun by the Konbaung Dynasty of Burma failed to take Ayutthaya but took northern Taninthayi. The Burmese–Siamese War (1765–1767) resulted in the sack of the city of Ayutthaya and the debellation of the kingdom in April 1767.

Fall

.jpg.webp)

The first Burmese invasion in 1759-60, from the newly ascendant Konbaung dynasty, besieged Ayutthaya but failed to capture the city, but successfully took the Tenasserim port city of Tavoy (Dawei), permanently seizing it from Siamese control.

In 1765, a combined 40,000-strong Burmese force invaded the territories of Ayutthaya from the north and west.[39]: 250 Major outlying towns quickly capitulated. After a 14-month siege, the city of Ayutthaya capitulated and was burned in April 1767.[62]: 218 Ayutthaya's art treasures, the libraries containing its literature, and the archives housing its historic records were almost totally destroyed,[62] and the Burmese brought the Ayutthaya Kingdom to ruin.[62] Lieberman states that, "hundreds of thousands possibly died during the [1765-67] Burmese invasion."[64]

Burmese rule lasted a mere few months. The Burmese, who had also been fighting a simultaneous war with the Chinese since 1765, were forced to withdraw in early-1768 when Chinese forces threatened their own capital.[39]: 253

With most Burmese forces having withdrawn, the country was reduced to chaos. All that remained of the old capital were some ruins of the royal palace. Provinces proclaimed independence under generals, rogue monks, and members of the royal family.

One general, Phraya Taksin, former governor of Tak and of Siamese-Chinese descent, began the reunification effort.[65][66] He gathered forces and began striking back at the Burmese, using his connections to the Chinese community to lend him significant resources and political support.[67][16] He finally established a capital at Thonburi, across the Chao Phraya from the present capital, Bangkok. Taak-Sin ascended the throne, becoming known as King Taak-Sin or Taksin.[65][66]

The ruins of the historic city of Ayutthaya and "associated historic towns" in the Ayutthaya Historical Park have been listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Site.[68] The city of Ayutthaya was refounded near the old city, and is now capital of Ayutthaya Province.[69]

Government

Kings

The kings of Ayutthaya were absolute monarchs with semi-religious status. Their authority derived from the ideologies of Hinduism and Buddhism as well as from natural leadership. The king of Sukhothai was the inspiration of Inscription 1 found in Sukhothai, which stated that King Ramkhamhaeng would hear the petition of any subject who rang the bell at the palace gate. The king was thus considered as a father by his people.

At Ayutthaya, however, the paternal aspects of kingship disappeared. The king was considered the chakkraphat (Sanskrit chakravartin) who through his adherence to the law made all the world revolve around him.[70] According to Hindu tradition, the king is the avatar of Vishnu, destroyer of demons, who was born to be the defender of the people. The Buddhist belief in the king is as righteous ruler (Sanskrit: dharmaraja) who strictly follows the teaching of Gautama Buddha and aims at the well-being of his people.

The kings' official names were reflections of those religions: Hinduism and Buddhism. They were considered as the incarnation of various Hindu gods: Indra, Shiva, or Vishnu (Rama). The coronation ceremony was directed by brahmins as the Hindu god Shiva was "lord of the universe". However, according to the codes, the king had the ultimate duty as protector of the people and the annihilator of evil.

According to Buddhism, the king was also believed to be a bodhisattva. One of the most important duties of the king was to build a temple or a Buddha statue as a symbol of prosperity and peace.[70]

For locals, another aspect of the kingship was also the analogy of "The Lord of the Land" or "He who Rules the Earth" (Phra Chao Phaendin). According to the court etiquette, a special language, Rachasap (Sanskrit: Rājāśabda, 'royal language'), was used to communicate with or about royalty.[71] In Ayutthaya, the king was said to grant control over land to his subjects, from nobles to commoners, according to the sakna or sakdina system[72] codified by King Borommatrailokkanat (1448–88). The sakdina system was similar to, but not the same as feudalism, under which the monarch does not own the land.[73] While there is no concrete evidence that this land management system constituted a formal palace economy, the French François-Timoléon de Choisy, who came to Ayutthaya in 1685, wrote, "the king has absolute power. He is truly the god of the Siamese: no-one dares to utter his name." Another 17th century writer, the Dutchman Jan van Vliet, remarked that the King of Siam was "honoured and worshipped by his subjects second to god." Laws and orders were issued by the king. For sometimes the king himself was also the highest judge who judged and punished important criminals such as traitors or rebels.[74]

In addition to the sakdina system, another of the numerous institutional innovations of Borommatrailokkanat was to adopt the position of uparaja, translated as 'viceroy' or 'prince', usually held by the king's senior son or full brother, in an attempt to regularise the succession to the throne—a particularly difficult feat for a polygamous dynasty. In practice, there was inherent conflict between king and uparaja and frequent disputed successions.[75] However, it is evident that the power of the throne of Ayutthaya had its limits. The hegemony of the Ayutthaya king was always based on his charisma based on his age and supporters. Without supporters, bloody coups took place from time to time. The most powerful figures of the capital were always generals, or the Minister of Military Department, Kalahom. During the last century of Ayutthaya, bloody fighting among princes and generals, aiming at the throne, plagued the court.

With the exception of Naresuan's succession by Ekathotsarot in 1605, 'the method of royal succession at Ayutthaya throughout the seventeenth century was battle.'[76] Although European visitors to Thailand at the time tried to discern any rules in the Siamese order of succession, noting that in practice the dead king's younger brother often succeeded him, this custom appears not to have been enshrined anywhere.[76] The ruling king did often bestow the title of uparaja upon his preferred successor, but in reality, it was an 'elimination process': any male member of the royal clan (usually the late king's brothers and sons) could claim the throne of Ayutthaya for himself, and win by defeating all his rivals.[76] Moreover, groupings of nobles, foreign merchants, and foreign mercenaries actively rallied behind their preferred candidates in hopes of benefiting from each war's outcome.[76]

Mandala system

Ayutthaya politically followed the mandala system, commonly used throughout Southeast Asia kingdoms before the 19th century. In the 17th century, the Ayutthaya monarchs were able to frequently appoint non-natives as governors of Ayutthaya-controlled towns and cities, in order to prevent competition from its nobility. By the end of the Ayutthaya period, the Siamese capital held strong sway over the polities in the lower Chao Phraya plain but had a gradually looser control of polities the further away from the capital at Ayutthaya.[77] The Thai historian Sunait Chutintaranond notes, "the view that Ayudhya was a strong centralized state" did not hold and that "in Ayudhya the hegemony of provincial governors was never successfully eliminated."[78][79]

Political development

Social classes

The reforms of King Borommatrailokkanat (r. 1448–1488) placed the king of Ayutthaya at the centre of a highly stratified social and political hierarchy that extended throughout the realm. Despite a lack of evidence, it is believed that in the Ayutthaya Kingdom, the basic unit of social organization was the village community composed of extended family households. Title to land resided with the headman, who held it in the name of the community, although peasant proprietors enjoyed the use of land as long as they cultivated it.[80] The lords gradually became courtiers (อำมาตย์) and tributary rulers of minor cities. The king ultimately came to be recognized as the earthly incarnation of Shiva or Vishnu and became the sacred object of politico-religious cult practices officiated over by royal court brahmans, part of the Buddhist court retinue. In the Buddhist context, the devaraja (divine king) was a bodhisattva. The belief in divine kingship prevailed into the 18th century, although by that time its religious implications had limited impact.

Ranking of social classes

With ample reserves of land available for cultivation, the realm depended on the acquisition and control of adequate manpower for farm labor and defense. The dramatic rise of Ayutthaya had entailed constant warfare and, as none of the parties in the region possessed a technological advantage, the outcome of battles was usually determined by the size of the armies. After each victorious campaign, Ayutthaya carried a number of conquered people back to its own territory, where they were assimilated and added to the labour force.[80] Ramathibodi II (r. 1491–1529) established a corvée system under which every freeman had to be registered as a phrai (servant) with the local lords, chao nai (เจ้านาย). When war broke out, male phrai were subject to impressment. Above the phrai was a nai (นาย), who was responsible for military service, corvée labour on public works, and on the land of the official to whom he was assigned. Phrai Suay (ไพร่ส่วย) met labour obligations by paying a tax. If he found the forced labour under his nai repugnant, he could sell himself as a that (ทาส, 'slave') to a more attractive nai or lord, who then paid a fee in compensation for the loss of corvée labour. As much as one-third of the manpower supply into the 19th century was composed of phrai.[80]

Wealth, status, and political influence were interrelated. The king allotted rice fields to court officials, provincial governors, and military commanders, in payment for their services to the crown, according to the sakdina system. Understandings of this system have been evaluated extensively by Thai social scientists like Jit Phumisak and Kukrit Pramoj. The size of each official's allotment was determined by the number of commoners or phrai he could command to work it. The amount of manpower a particular headman, or official, could command determined his status relative to others in the hierarchy and his wealth. At the apex of the hierarchy, the king, who was symbolically the realm's largest landholder, theoretically commanded the services of the largest number of phrai, called phrai luang ('royal servants'), who paid taxes, served in the royal army, and worked on the crown lands.[80]

However, the recruitment of the armed forces depended on nai, or mun nai, literally meaning 'lord', officials who commanded their own phrai som, or 'subjects'. These officials had to submit to the king's command when war broke out. Officials thus became the key figures in the kingdom's politics. At least two officials staged coups, taking the throne themselves while bloody struggles between the king and his officials, followed by purges of court officials, were common.[80]

King Trailok, in the early-16th century, established definite allotments of land and phrai for the royal officials at each rung in the hierarchy, thus determining the country's social structure until the introduction of salaries for government officials in the 19th century.[80]

| Social class | Description |

|---|---|

| munnai | Tax-exempt administrative elite in the capital and administrative centres.[81]: 272 |

| phrai luang | Royal servicemen who worked a specified period each year (possibly six months) for the crown.[81]: 271 They were normally prevented from leaving their village except to perform corvées or military services.[81]: 273 |

| phrai som | Commoners with no obligation to the crown. They vastly outnumbered the phrai luang.[81]: 271 |

Outside this system to some extent were the sangha (Buddhist monastic community), which all classes of men could join, and the overseas Chinese. Wats became centers of Thai education and culture, while during this period the Chinese first began to settle in Thailand and soon began to establish control over the country's economic life.[80]

The Chinese were not obliged to register for corvée duty, so they were free to move about the kingdom at will and engage in commerce. By the 16th century, the Chinese controlled Ayutthaya's internal trade and had found important places in civil and military service. Most of these men took Thai wives as few women left China to accompany the men.[80]

Uthong was responsible for the compilation of a Dharmaśāstra, a legal code based on Hindu sources and traditional Thai custom. The Dharmaśāstra remained a tool of Thai law until late in the 19th century. A bureaucracy based on a hierarchy of ranked and titled officials was introduced, and society was organized in a related manner. However, the caste system was not adopted.[82]

The 16th century witnessed the rise of Burma, which had overrun Chiang Mai in the Burmese-Siamese War of 1563-1564. In 1569, Burmese forces, joined by Thai rebels, mostly royal family members of Thailand, captured the city of Ayutthaya and carried off the whole royal family to Burma (Burmese-Siamese War 1568-70). Dhammaraja (1569–90), a Thai governor who had aided the Burmese, was installed as vassal king at Ayutthaya. Thai independence was restored by his son, King Naresuan (1590–1605), who turned on the Burmese and by 1600 had driven them from the country.[83]

Determined to prevent another treason like his father's, Naresuan set about unifying the country's administration directly under the royal court at Ayutthaya. He ended the practice of nominating royal princes to govern Ayutthaya's provinces, assigning instead court officials who were expected to execute policies handed down by the king. Thereafter royal princes were confined to the capital. Their power struggles continued, but at court under the king's watchful eye.[84]

To ensure his control over the new class of governors, Naresuan decreed that all freemen subject to phrai service had become phrai luang, bound directly to the king, who distributed the use of their services to his officials. This measure gave the king a theoretical monopoly on all manpower, and the idea developed that since the king owned the services of all the people, he also possessed all the land. Ministerial offices and governorships—and the sakdina that went with them—were usually inherited positions dominated by a few families often connected to the king by marriage. Indeed, marriage was frequently used by Thai kings to cement alliances between themselves and powerful families, a custom prevailing through the 19th century. As a result of this policy, the king's wives usually numbered in the dozens.[84]

Even with Naresuan's reforms, the effectiveness of the royal government over the next 150 years was unstable. Royal power outside the crown lands—in theory, absolute—was in practice limited by the laxity of the civil administration. The influence of central government and the king was not extensive beyond the capital. When war with the Burmese broke out in the late 18th century, provinces easily abandoned the capital. As the enforcing troops were not easily rallied to defend the capital, the city of Ayutthaya could not stand against the Burmese aggressors.[84]

Military

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Ayutthaya's military was the origin of the Royal Thai Army. The army was organized into a small standing army of a few thousand, which defended the capital and the palace, and a much larger conscript-based wartime army. Conscription was based on the Phrai system (including phrai luang and phrai som), which required local chiefs to supply their predetermined quota of men from their jurisdiction on the basis of population in times of war. This basic system of military organization was largely unchanged down to the early Rattanakosin period.

The main weaponry of the infantry largely consisted of swords, spears and bow and arrows. The infantry units were supported by cavalry and elephantry corps.

Culture and society

Language

The Siamese (Thai) language was initially spoken only by the Ayutthaya elite, but gradually grew to transcend social classes and becoming widespread throughout the kingdom by the Late Ayutthaya Period (late 17th-18th centuries),[86] although the Mon language was spoken among everyday people throughout the Chao Phraya delta until as late as c. 1515.[87] The Khmer language was an early prestige language of the Ayutthaya court, until it was supplanted by the Siamese language,[88] however it was still continually spoken by the ethnic Khmer community living in Ayutthaya. Many variants of Chinese were spoken, with the substantial increase of the Chinese population in Ayutthaya, eventually becoming a large minority in the kingdom during the Late Ayutthaya Period.[89]

Various minority languages spoken inside the kingdom included Malay, Persian, Japanese, Cham, Dutch, Portuguese, etc...

Religion

Ayutthaya's main religion was Theravada Buddhism. However, many of the elements of the political and social system were incorporated from Hindu scriptures and were conducted by Brahmin priests.[82] Many areas of the kingdom also practiced Mahayana Buddhism, Islam[90] and, influenced by French Missionaries who arrived through China in the 17th century, some small areas converted to Roman Catholicism.[91] The influence of Mahayana and Tantric practices also entered Theravada Buddhism, producing a tradition called Tantric Theravada.

The natural world was also home to a number of spirits which are part of the Satsana Phi. Phi (Thai: ผี) are spirits of buildings or territories, natural places, or phenomena; they are also ancestral spirits that protect people, or can also include malevolent spirits. The phi which are guardian deities of places, or towns are celebrated at festivals with communal gatherings and offerings of food. The spirits run throughout Thai folklore.[92]

Phi were believed to influence natural phenomena including human illness and thus the baci became an important part of people identity and religious health over the millennia. Spirit houses were an important folk custom which were used to ensure balance with the natural and supernatural world. Astrology was also a vital part to understanding the natural and spiritual worlds and became an important cultural means to enforce social taboos and customs.

Arts and performances

.jpg.webp)

The myth and epic stories of Ramakien provide the Siamese with a rich source of dramatic materials. The royal court of Ayutthaya developed classical dramatic forms of expression called khon (Thai: โขน) and lakhon (Thai: ละคร). Ramakien played a role in shaping these dramatic arts. During the Ayutthaya period, khon, or a dramatized version of Ramakien, was classified as lakhon nai or a theatrical performance reserved only for aristocratic audience. The Siamese drama and classical dance later spread throughout mainland Southeast Asia and influenced the development of high-culture art in most countries, including Burma, Cambodia, and Laos.[93]

Historical evidence shows that the Thai art of stage plays must have already been highly evolved by the 17th century. Louis XIV, the Sun King of France, had a formal diplomatic relation with Ayutthaya's King Narai. In 1687, France sent the diplomat Simon de la Loubère to record all that he saw in the Siamese Kingdom. In his famous account Du Royaume de Siam, La Loubère carefully observed the classic 17th century theatre of Siam, including an epic battle scene from a khon performance, and recorded what he saw in great detail:

The Siamese have three sorts of Stage Plays: That which they call Cone [khôn] is a figure dance, to the sound of the violin and some other instruments. The dancers are masked and armed, and represent rather a combat than a dance. And though every one runs into high motions, and extravagant postures, they cease not continually to intermix some word. Most of their masks are hideous, and represent either monstrous Beasts, or kinds of Devils. The Show which they call Lacone is a poem intermix with Epic and Dramatic, which lasts three days, from eight in the morning till seven at night. They are histories in verse, serious, and sung by several actors always present, and which do only sing reciprocally .... The Rabam is a double dance of men and women, which is not martial, but gallant ... they can perform it without much tying themselves, because their way of dancing is a simple march round, very slow, and without any high motion; but with a great many slow contortions of the body and arms.[94]

Of the attire of Siamese Khôn dancers, La Loubère recorded that, "[T]hose that dance in Rabam, and Cone, have gilded paper-bonnets, high and pointed, like the Mandarins caps of ceremony, but which hang down at the sides below their ears, which are adorned with counterfeit stones, and with two pendants of gilded wood."[94]

La Loubère also observed the existence of muay Thai and muay Laos, noting that they looked similar (i.e., using both fists and elbows to fight) but the hand-wrapping techniques were different.[94]

The accomplishment and influence of Thai art and culture, developed during the Ayutthaya period, on the neighboring countries was evident in the observation of James Low, a British scholar on Southeast Asia, during the early-Rattanakosin Era: "The Siamese have attained to a considerable degree of perfection in dramatic exhibitions – and are in this respect envied by their neighbours the Burmans, Laos, and Cambojans who all employ Siamese actors when they can be got."[93]: 177

Literature

Ayutthaya was a kingdom rich in literary production. Even after the sack of Ayutthaya in 1767, many literary masterpieces in the Thai language survived. However, Ayutthayan literature (as well as Thai literature before the modern era) was dominated by verse composition (i.e., poetry), whereas prose works were reserved to legal matters, records of state affairs and historical chronicles. Thus, there are many works in the nature of epic poetry in the Thai language. The Thai poetical tradition was originally based on indigenous poetical forms such as rai (ร่าย), khlong (โคลง), kap (กาพย์) and klon (กลอน). Some of these poetical forms—notably khlong—have been shared between the speakers of tai languages since ancient time (before the emergence of Siam).

Tamil influence on the Siamese language

Through Buddhist and Hindu influence, a variety of Chanda prosodic meters were received via Ceylon. Since the Thai language is mono-syllabic, a huge number of loan words from Sanskrit, Tamil and Pali are needed to compose these classical Sanskrit meters. According to B.J. Terwiel, this process occurred with an accelerated pace during the reign of King Boromma-Trailokkanat (1448-1488) who reformed Siam's model of governance by turning the Siamese polity into an empire under the mandala feudal system.[95]: 307–326 The new system demanded a new imperial language for the noble class. This literary influence changed the course of the Thai or Siamese language, setting it apart from other tai languages, by increasing the number of Sanskrit and Pali words drastically and imposing the demand on the Thais to develop a writing system that preserves the orthography of Sanskrit words for literary purpose. By the 15th century, the Thai language had evolved into a distinctive medium along with a nascent literary identity of a new nation. It allowed Siamese poets to compose in different poetical styles and mood, from playful and humorous rimed verses, to romantic and elegant klong and to polished and imperious chan prosodies modified from classical Sanskrit meters. Thai poets experimented with these different prosodic forms, producing innovative "hybrid" poems such as Lilit (Thai: ลิลิต, an interleave of khlong and kap or rai verses) or Kap hor Klong (Thai: กาพย์ห่อโคลง - khlong poems enveloped by kap verses). The Thai thus developed a keen mind and a keen ear for poetry. To maximize this new literary medium, however, an intensive classical education in Pali was required. This made poetry an exclusive occupation of the noble classes. However, B.J. Terwiel notes, citing a 17th-century text book Jindamanee, that scribes and common Siamese men, too, were encouraged to learn basic Pali and Sanskrit for career advancement.[95]: 322–323

Ramakien

Most countries in Southeast Asia share an Indianised culture. Traditionally, therefore, Thai literature was heavily influenced by the Indian culture and Buddhist-Hindu ideology since the time it first appeared in the 13th century. Thailand's national epic is a version of the story of Rama-Pandita, as recounted by Gotama Buddha in the Dasharatha Jataka called the Ramakien,[96] translated from Pali and rearranged into Siamese verses. The importance of the Ramayana epic in Thailand is due to the Thai's adoption of the Hindu religio-political ideology of kingship, as embodied by Rama. The Siamese capital, Ayutthaya, was named after the holy city of Ayodhya, the city of Rama. Thai kings of the current dynasty from Rama VI forward, and retroactively, have been referred to as "Rama" to the present day (relations with the west caused the crown to seek a brief name to convey royalty to both Thais and foreigners, following European styles).

A number of versions of the Ramakien epic were lost in the destruction of Ayutthaya in 1767. Three versions currently exist. One of these was prepared under the supervision (and partly written by) King Rama I. His son, Rama II, rewrote some parts for khon drama. The main differences from the original are an extended role for the monkey god Hanuman and the addition of a happy ending. Many of popular poems among the Thai nobles are also based on Indian stories. One of the most famous is Anirut Kham Chan which is based on an ancient Indian story of Prince Anirudha.

Khun Chang Khun Phaen: the Siamese epic folk poem

In the Ayutthaya period, folktales also flourished. One of the most famous folktales is the story of Khun Chang Khun Phaen (Thai: ขุนช้างขุนแผน), referred to in Thailand simply as "Khun Phaen", which combines the elements of romantic comedy and heroic adventures, ending in high tragedy. The epic of Khun Chang Khun Phaen (KCKP) revolves around Khun Phaen, a Siamese general with superhuman magical powers who served the King of Ayutthaya, and his love-triangle relationship between himself, Khun Chang, and a beautiful Siamese girl named Wan-Thong. The composition of KCKP, much like other orally-transmitted epics, evolved over time. It originated as a recitation or sepha within the Thai oral tradition from around the beginning of the 17th century (c. 1600). Siamese troubadours and minstrels added more subplots and embellished scenes to the original story line as time went on.[97] By the late period of the Ayutthaya Kingdom, it had attained the current shape as a long work of epic poem with the length of about 20,000 lines, spanning 43 samut thai books. The version that exists today was composed with klon meter throughout and is referred to in Thailand as nithan Kham Klon (Thai: นิทานคำกลอน) meaning a 'poetic tale'.

Architecture

_%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8%B1%E0%B8%94%E0%B8%A1%E0%B8%AB%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%98%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%95%E0%B8%B8_%E0%B8%AD.%E0%B8%9E%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B0%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%84%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%A8%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B5%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%B8%E0%B8%98%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%B2_%E0%B8%88.%E0%B8%9E%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B0%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%84%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%A8%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B5%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%B8%E0%B8%98%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%B2_(6).jpg.webp)

The Ayutthaya Buddhist temple falls into one of two broad categories: the stupa-style solid temple and the prang-style (Thai: ปรางค์). The prangs can also be found in various forms in Sukhothai, Lopburi, Bangkok (Wat Arun). Sizes may vary, but usually the prangs measure between 15 and 40 meters in height, and resemble a towering corn-cob like structure.

Prangs essentially represent Mount Meru. In Thailand Buddha relics were often housed in a vault in these structures, reflecting the belief that the Buddha is a most significant being, having attained enlightenment and having shown the path to enlightenment to others.[99]

Notable archeological sites

| Name | Picture | Built | Sponsor(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan Palace, Phitsanulok |  |

Built during the Sukhothai period (1238–1438) | King Maha Thammaracha I of Sukhothai | Former royal residence of the Front Palaces of Ayutthaya, King Trailokanat, and King Naresuan, used as a royal residence from the Sukhothai period until the reign of Naresuan |

| Chedi Phukhao Thong | .jpg.webp) |

1587 (rebuilt in 1744)[100] | Prince (later King) Naresuan King Borommakot[100] |

Built to commemorate a battle victory following Ayutthaya's liberation from Burma in 1584[100] |

| Elephant Kraal Pavilion (พระที่นั่งเพนียด) |  |

16th century[101] | Royal elephant kraal formerly used by Ayutthaya monarchs, one of the few still existing in Thailand. Used as an elephant camp today. | |

| Front Palace, Ayutthaya |  |

Main residence of the Front Palaces of Ayutthaya. Restored by King Mongkut. Currently houses the Chan Kasem National Museum.[102] | ||

| King Narai's Palace, Lopburi |  |

1666 | King Narai | Palace of King Narai from 1666 until his death in 1688 |

| Prasat Nakhon Luang |  |

1631[103][104] | King Prasat Thong | Mostly reconstructed during the reign of King Rama V. |

| Wat Chai Watthanaram |  |

1630 | King Prasat Thong | |

| Wat Ko Kaew Suttharam, Phetchaburi |  |

1734[105] | King Borommakot[105] | One of the best examples of 18th-century Ayutthaya temple (wat) murals |

| Wat Kudi Dao |  |

Before 1711[106] | Prince, later King Borommakot[106] | A good example of 18th-century Late Ayutthaya architecture. Partially restored.[106] |

| Wat Mahathat |  |

1374 | King Borommarachathirat I | |

| Wat Na Phra Men |  |

1503[107] | King Ramathibodi II | One of the best preserved Ayutthaya temples. Survived the Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767. Restored during the reign of Rama III (r. 1824-51).[107] |

| Wat Phanan Choeng |  |

1324 | Built 27 years before the founding of Ayutthaya. Revered temple still in use. | |

| Wat Phra Ram |  |

1369 | King Ramesuan | |

| Wat Phra Phutthabat (วัดพระพุทธบาท), Saraburi |

.jpg.webp) |

1624[108] | King Songtham | Pilgrimage site in Thailand up to the present. |

| Wat Phra Si Sanphet | %252C_Ayutthaya%252C_Thailand.jpg.webp) |

1351 | King Ramathibodi I | |

| Wat Phutthaisawan |  |

Before 1351 | King Ramathibodi I | Built before Ayutthaya was founded; birthplace of Thai krabi-krabong sword fighting |

| Wat Ratchaburana | .jpg.webp) |

1424 | King Borommarachathirat II | |

| Wat Thammikarat |  |

Before 1351 | ||

| Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon |  |

1357[109] | King Ramathibodi I[109] | |

| Wihan Phra Mongkhon Bophit | .jpg.webp) |

Heavily renovated during the reign of King Borommakot (r. 1733-1758) | King Borommakot | Heavily damaged by the Burmese sack in 1767, the wihan's current appearance is largely from King Borommakot's major renovations of the temple in the 18th century. Largely reconstructed in the mid-20th century.[110] |

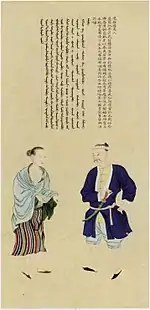

Clothing

Three clothing styles were evident in the Ayutthaya period. Each style depended on social class.

1. Court clothing (worn by the king, queen, concubines, and senior government officials):

- Men: The king wore mongkut (Thai: มงกุฎ), as headgear, round Mandarin collar with khrui and wore chong kben (Thai: โจงกระเบน), as trousers.

- Court officers, (who served in the royal palace) wore lomphok, as headgear, khrui, and wore chong kben.

- Women The queen wore chada (Thai: ชฎา), as headgear, sabai (Thai: สไบ), (a breast cloth that wrap over one shoulder around chest and back) and wore pha nung (Thai: ผ้านุ่ง), as a skirt.

- Concubines wore long hair, sabai, and pha nung.

2. Nobles (rich citizens):

- Men: wore mandarin collar shirt, a mahadthai hair style (Thai: ทรงมหาดไทย), and wore chong kben.

- Women: wore the sabai and pha nung.

3. Villagers:

- Men: wore a loincloth, displayed a naked chest, a mahadthai hair style, sometimes wore sarong or chong kben.

- Women: wore the sabai and pha nung.

Economy

.jpg.webp)

Light Green - territories conquered or ceded

Dark Green (Allied) - Ayutthaya

Yellow - Main Factories

The Thais never lacked a rich food supply. Peasants planted rice for their own consumption and to pay taxes. Whatever remained was used to support religious institutions. From the 13th to the 15th centuries, however, a transformation took place in Thai rice cultivation. In the highlands, where rainfall had to be supplemented by a system of irrigation[112] to control water levels in flooded paddies, the Thais sowed the glutinous rice that is still the staple in the geographical regions of the north and northeast. But in the floodplain of the Chao Phraya, farmers turned to a different variety of rice—the so-called floating rice, a slender, non-glutinous grain introduced from Bengal—that would grow fast enough to keep pace with the rise of the water level in the lowland fields.[113]

The new strain grew easily and abundantly, producing a surplus that could be sold cheaply abroad. Ayutthaya, at the southern extremity of the floodplain, thus became the hub of economic activity. Under royal patronage, corvée labour dug canals on which rice was brought from the fields to the king's ships for export to China. In the process, the Chao Phraya delta—mud flats between the sea and firm land hitherto considered unsuitable for habitation—was reclaimed and cultivated. Traditionally the king had a duty to perform a religious ceremony to bless the rice planting.[113]

Although rice was abundant in Ayutthaya, rice exports were banned from time to time when famine occurred because of natural calamity or war. Rice was usually bartered for luxury goods and armaments from Westerners, but rice cultivation was mainly for the domestic market and rice export was evidently unreliable.

Currency

Ayutthaya officially used cowrie shells, prakab (baked clay coins), and pod duang as currencies. Pod duang became the standard medium of exchange from the early-13th century to the reign of King Chulalongkorn.

Ayutthaya as international trading port

Trade with Europeans was lively in the 17th century. In fact European merchants traded their goods, mainly modern arms such as rifles and cannons, for local products from the inland jungle such as sappan (lit. 'bridge') woods, deerskin, and rice. Tomé Pires, a Portuguese voyager, mentioned in the 16th century that Ayutthaya, or Odia, was "rich in good merchandise". Most of the foreign merchants coming to Ayutthaya were European and Chinese, and were taxed by the authorities. The kingdom had an abundance of rice, salt, dried fish, arrack, and vegetables.[114]

Trade with foreigners, mainly the Dutch, reached its peak in the 17th century. Ayutthaya became a main destination for merchants from China and Japan. It was apparent that foreigners began taking part in the kingdom's politics. Ayutthaya's kings employed foreign mercenaries who sometimes joined the wars with the kingdom's enemies. However, after the purge of the French in the late-17th century, the major traders with Ayutthaya were the Chinese. The Dutch from the Dutch East Indies Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC), were still active. Ayutthaya's economy declined rapidly in the 18th century, until the Burmese invasion caused the total collapse of Ayutthaya's economy in 1767.[115]

Contacts with the West

In 1511, immediately after having conquered Malacca, the Portuguese sent a diplomatic mission headed by Duarte Fernandes to the court of King Ramathibodi II of Ayutthaya. Having established amicable relations between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Kingdom of Siam, they returned with a Siamese envoy who carried gifts and letters to the King of Portugal.[116] The Portuguese were the first Europeans to visit the country. Five years after that initial contact, Ayutthaya and Portugal concluded a treaty granting the Portuguese permission to trade in the kingdom. A similar treaty in 1592 gave the Dutch a privileged position in the rice trade.

Foreigners were cordially welcomed at the court of Narai (1657–1688), a ruler with a cosmopolitan outlook who was nonetheless wary of outside influence. Important commercial ties were forged with Japan. Dutch and English trading companies were allowed to establish factories, and Thai diplomatic missions were sent to Paris and The Hague. By maintaining these ties, the Thai court skillfully played off the Dutch against the English and the French, avoiding the excessive influence of a single power.[117]

In 1664, however, the Dutch used force to exact a treaty granting them extraterritorial rights as well as freer access to trade. At the urging of his foreign minister, the Greek adventurer Constantine Phaulkon, Narai turned to France for assistance. French engineers constructed fortifications for the Thais and built a new palace at Lopburi for Narai. In addition, French missionaries engaged in education and medicine and brought the first printing press into the country. Louis XIV's personal interest was aroused by reports from missionaries suggesting that Narai might be converted to Christianity.[118]

The French presence encouraged by Phaulkon, however, stirred the resentment and suspicions of the Thai nobles and Buddhist clergy. When word spread that Narai was dying, a general, Phetracha (reigned 1688–1693) staged a coup d'état, the 1688 Siamese revolution, seized the throne, killed the designated heir, a Christian, and had Phaulkon put to death along with a number of missionaries. He then expelled the remaining foreigners. Some studies said that Ayutthaya began a period of alienation from Western traders, while welcoming more Chinese merchants. But other recent studies argue that, due to wars and conflicts in Europe in the mid-18th century, European merchants reduced their activities in the East. However, it was apparent that the Dutch East Indies Company or VOC was still doing business in Ayutthaya despite political difficulties.[118]

Dutch East India Company merchant ship.

Dutch East India Company merchant ship. Memorial plate in Lopburi showing King Narai with French ambassadors.

Memorial plate in Lopburi showing King Narai with French ambassadors..jpg.webp) The French ambassador Chevalier de Chaumont presents a letter from Louis XIV to King Narai. Constance Phaulkon is seen kowtowing in the lower left corner of the print

The French ambassador Chevalier de Chaumont presents a letter from Louis XIV to King Narai. Constance Phaulkon is seen kowtowing in the lower left corner of the print Siamese embassy to Louis XIV in 1686, by Nicolas de Larmessin.

Siamese embassy to Louis XIV in 1686, by Nicolas de Larmessin. French Jesuits observing an eclipse with King Narai and his court in April 1688, shortly before the Siamese revolution.

French Jesuits observing an eclipse with King Narai and his court in April 1688, shortly before the Siamese revolution. Ok-khun Chamnan, a Siamese ambassador who visited France and Rome on an embassy in 1688

Ok-khun Chamnan, a Siamese ambassador who visited France and Rome on an embassy in 1688 A portrait of Kosa Pan, a Thai ambassador accredited by King Narai of Ayutthaya to the court of King Louis XIV of France, by Charles Le Brun, 1686

A portrait of Kosa Pan, a Thai ambassador accredited by King Narai of Ayutthaya to the court of King Louis XIV of France, by Charles Le Brun, 1686

Contacts with East Asia

Between 1405 and 1433, the Chinese Ming dynasty sponsored a series of seven naval expeditions. Emperor Yongle designed them to establish a Chinese presence, impose imperial control over trade, and impress foreign peoples in the Indian Ocean basin. He also might have wanted to extend the tributary system. It is believed that the Chinese fleet under Admiral Zheng He travelled up the Chao Phraya River to Ayutthaya on three occasions.

Meanwhile, a Japanese colony was established in Ayutthaya. The colony was active in trade, particularly in the export of deer hides and saphan wood to Japan in exchange for Japanese silver and Japanese handicrafts (swords, lacquered boxes, high-quality paper). From Ayutthaya, Japan was interested in purchasing Chinese silks, as well as deerskins and ray or shark skins (used to make a sort of shagreen for Japanese sword handles and scabbards).[119]

The Japanese quarters of Ayutthaya were home to about 1,500 Japanese inhabitants (some estimates run as high as 7,000). The community was called Ban Yipun in Thai, and was headed by a Japanese chief nominated by Thai authorities.[120] It seems to have been a combination of traders, Christian converts (Kirishitan) who had fled their home country to various Southeast Asian countries following the persecutions of Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, and unemployed former samurai who had been on the losing side at the battle of Sekigahara.[120]

Padre António Francisco Cardim recounted having administered the sacrament to around 400 Japanese Christians in 1627 in the Thai capital of Ayuthaya ("a 400 japoes christaos")[120] There were also Japanese communities in Ligor and Patani.[121]

Early 17th-century Chinese woodblock print, thought to represent Zheng He's ships.

Early 17th-century Chinese woodblock print, thought to represent Zheng He's ships. Luang Pho Tho or Sam Pao Kong, the highly revered Buddha statue in Wat Phanan Choeng temple was visited in 1407 by Zheng He during the naval expedition.

Luang Pho Tho or Sam Pao Kong, the highly revered Buddha statue in Wat Phanan Choeng temple was visited in 1407 by Zheng He during the naval expedition. A 1634 Japanese Red seal ship. Tokyo Naval Science Museum.

A 1634 Japanese Red seal ship. Tokyo Naval Science Museum. The Japanese quarter in Ayutthaya is indicated at the bottom center ("Japonois") of the map.

The Japanese quarter in Ayutthaya is indicated at the bottom center ("Japonois") of the map. Portrait of Yamada Nagamasa c.1630.

Portrait of Yamada Nagamasa c.1630. Interior of the Japanese Village museum in Ayutthaya

Interior of the Japanese Village museum in Ayutthaya

Notable foreigners, 17th century Ayutthaya

- Constantine Phaulkon, Greek adventurer and first councillor of King Narai

- François-Timoléon de Choisy

- Father Guy Tachard, French Jesuit writer and Siamese Ambassador to France (1688)

- Louis Laneau, Apostolic Vicar of Siam

- Claude de Forbin, French Admiral

- Yamada Nagamasa, Japanese adventurer who became the ruler of the Nakhon Si Thammarat

- George White (merchant), English merchant

- Jeremias van Vliet, Dutch Opperhoofd

Historiography

The history of the Ayutthaya Kingdom overall has been a neglected period of historiography in Thailand, as well as abroad, characterized by well-researched and popular histories of subperiods of Ayutthaya. Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit's "A History of Ayutthaya: Siam In the Early Modern World", published in 2017, was the first English-academic book to have analyzed the full four hundred years of the Ayutthaya Kingdom's existence. The historiography of Southeast Asia originated from post-colonial capitals. As Thailand had never been fully colonized, it never had a European patron from which national histories could be written about themselves until the arrival of the Americans in the 1960s.[122][43]

Early Rattanakosin period documents traced their "national" origins to the founding of Ayutthaya in 1351. In the early 20th-century however, Thai elites, influenced by Western ideas of European nationalism and the nation state, used that framework to create a nationalist history of Thailand, implementing it in ways deemphasized Ayutthaya's importance to Thai history by portraying the Sukhothai Kingdom as the first "Thai" kingdom or golden age of "Thai-ness" (Buddhism, Thai-style democracy, free trade, abolition of slavery), Rattanakosin as the "rebirth", and Ayutthaya as a period of decline between Sukhothai and Rattanakosin. This resulted in Ayutthaya being largely forgotten in the historiography of Thailand for half a century following the works of Prince Damrong in the early 20th century.[123][124]

The nationalist-themed histories of Ayutthaya, pioneered by Prince Damrong, primarily featured the stories of kings fighting wars and the idea of Eurocentric territorial subjugation of neighboring states. These historical themes remains influential in Thailand and in Thai popular history up until the present, which has only been challenged by a newer generation of historians and academics in Thailand and abroad starting in the 1980s, emphasizing the long-neglected commercial and economic aspects which were important to Ayutthaya. New released sources and translations from a variety of historical records (China, the Netherlands, etc...) have made the researching of Ayutthaya history more accessible in the past two and three decades.[43][125]

Since the 1970s, newer generations of academics have come up and challenged the old historiography, paying more attention and publishing works about the history of Ayutthaya, prominently beginning with Charnvit Kasetsiri's "The Rise of Ayudhya", published in 1977.[126][127][128][129] Kasetsiri, in 1999, argues that, "Ayutthaya was the first major political, cultural, and commercial center of the Thai."[130][131]

The idea that Ayutthaya suffered a decline following the departure of Europeans in the late 17th century was an idea popularized, at first, in the Rattanakosin court, in an attempt to legitimize the new dynasty over the Ayutthaya Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty, and more contemporarily by Anthony Reid's book on the "Age of Commerce". However, more recent studies, such as by Victor Lieberman in "Strange Parallels in Southeast Asia" and by Baker and Phongpaichit in "A History of Ayutthaya", have mostly refuted Reid's hypothesis, in particular Lieberman criticizing Reid's methodology of using the example of Maritime Southeast Asia to explain Mainland Southeast Asia, citing the opening of Qing China's revocation of its maritime ban and the subsequent increase in trade between China and Siam and Ayutthaya's historical importance as a regional Asian trade center rather than one in which Europeans held any power or any significant influence for any extended period of time.[132][127][133][134]

Image gallery

Detached Buddha head encased in fig tree roots

Detached Buddha head encased in fig tree roots Seated Buddha, Ayutthaya

Seated Buddha, Ayutthaya Seated Buddha, Ayutthaya

Seated Buddha, Ayutthaya Ayutthaya Historical Park

Ayutthaya Historical Park Ayutthaya Historical Park

Ayutthaya Historical Park Ayutthaya skyline, photographed by John Thomson, early 1866

Ayutthaya skyline, photographed by John Thomson, early 1866 The main prang of Wat Mahathat, collapsed in 1904, photographed in the early 20th century

The main prang of Wat Mahathat, collapsed in 1904, photographed in the early 20th century Wihan Phra Mongkhon Bophit before restoration in the late 19th/20th century

Wihan Phra Mongkhon Bophit before restoration in the late 19th/20th century Interior of Wat Na Phra Men

Interior of Wat Na Phra Men

In popular culture

- Love Destiny (TV series) (Thai: บุพเพสันนิวาส; Bupphesanniwat), 2018 Thai historical television series.

- The Legend of Suriyothai, 2001 Thai biographical historical drama film series about Queen Suriyothai.

- King Naresuan (film), 2007–2015 Thai biographical historical drama film series about King Naresuan the Great.

See also

- Ayutthaya Historical Park

- Ayutthaya Province

- Baan Hollanda

- Bang Rajan

- Family tree of Ayutthaya kings

- History of Thailand

- List of Ayutthaya kings

Notes

- Roberts, Edmund (1837). "XVIII City of Bang-kok". Embassy to the Eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat in the U. S. sloop-of-war Peacock during the years 1832-3-4. Harper & Brothers. p. image 288. OCLC 12212199.

The spot on which the present capital stands, and the country in its vicinity, on both banks of the river for a considerable distance, were formerly, before the removal of the court to its present situation called Bang-kok; but since that time, and for nearly sixty years past, it has been named Sia yuthia, (pronounced See-ah you-tè-ah, and by the natives, Krung, that is, the capital;) it is called by both names here, but never Bang-kok; and they always correct foreigners when the latter make this mistake. The villages which occupy the right hand of the river, opposite to the capital, pass under the general name of Bang-kok.

Citations

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World (Kindle ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). ISBN 978-0521800860.

- "The Siam Society Lecture: A History of Ayutthaya (28 June 2017)". Youtube. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). ISBN 978-0521800860.