Perak

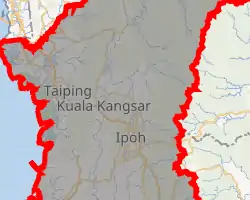

Perak (Malay pronunciation: [peraʔ]) is a state of Malaysia on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. Perak has land borders with the Malaysian states of Kedah to the north, Penang to the northwest, Kelantan and Pahang to the east, and Selangor to the south. Thailand's Yala and Narathiwat provinces both lie to the northeast. Perak's capital city, Ipoh, was known historically for its tin-mining activities until the price of the metal dropped, severely affecting the state's economy. The royal capital remains Kuala Kangsar, where the palace of the Sultan of Perak is located. As of 2018, the state's population was 2,500,000. Perak has diverse tropical rainforests and an equatorial climate. The state's mountain ranges belong to the Titiwangsa Range, which is part of the larger Tenasserim Range connecting Thailand, Myanmar and Malaysia. Perak's Mount Korbu is the highest point of the range.

Perak | |

|---|---|

State | |

| Perak Darul Ridzuan ڤيراق دار الرضوان | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Jawi | ڤيراق |

| • Chinese | 霹雳 (Simplified) 霹靂 (Traditional) |

| • Tamil | பேராக் Pērāk (Transliteration) |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): Perak Aman Jaya Perak Peace Success | |

| Anthem: Allah Lanjutkan Usia Sultan God Lengthen the Sultan's Age | |

| |

OpenStreetMap  | |

| Coordinates: 4°45′N 101°0′E | |

| Capital | Ipoh |

| Royal capital | Kuala Kangsar |

| Government | |

| • Type | Parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| • Sultan | Nazrin Shah |

| • Menteri Besar | Saarani Mohamad (BN–UMNO) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 20,976 km2 (8,099 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation (Mount Korbu) | 2,183 m (7,162 ft) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 2,500,000 (5th) |

| Demonym | Perakian |

| Demographics (2010)[2] | |

| • Ethnic composition | Malaysian Nationality: 97.1%

Native Malaysian & indigenous 57.1% (1,386,700) Chinese 29% (651,003), Indian 11% (253,061) Non-Malaysian Nationality: 2.9% |

| • Dialects | Perak Malay • Cantonese • Tamil Other ethnic minority languages |

| State Index | |

| • HDI (2018) | 0.809 (very high) (7th)[3] |

| • TFR (2017) | 1.9[1] |

| • GDP (2016) | RM65,958 million[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (MST[4]) |

| Postal code | |

| Calling code | 033 to 058[7] |

| ISO 3166 code | MY-08, 36–39[8] |

| Vehicle registration | A[9] |

| Pangkor Treaty | 1874 |

| Federated into FMS | 1895 |

| Japanese occupation | 1942 |

| Accession into the Federation of Malaya | 1948 |

| Independence as part of the Federation of Malaya | 31 August 1957 |

| Website | Official website |

The discovery of an ancient skeleton in Perak supplied missing information on the migration of Homo sapiens from mainland Asia through Southeast Asia to the Australian continent. Known as Perak Man, the skeleton is dated at around 10,000 years old. An early Hindu or Buddhist kingdom, followed by several other minor kingdoms, existed before the arrival of Islam. By 1528, a Muslim sultanate began to emerge in Perak, out of the remnants of the Malaccan Sultanate. Although able to resist Siamese occupation for more than two hundred years, the Sultanate was partly controlled by the Sumatra-based Aceh Sultanate. This was particularly the case after the Aceh lineage took over the royal succession. With the arrival of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), and the VOC's increasing conflicts with Aceh, Perak began to distance itself from Acehnese control. The presence of the English East India Company (EIC) in the nearby Straits Settlements of Penang provided additional protection for the state, with further Siamese attempts to conquer Perak thwarted by British expeditionary forces.

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 was signed to prevent further conflict between the British and the Dutch. It enabled the British to expand their control in the Malay Peninsula without interference from other foreign powers. The 1874 Pangkor Treaty provided for direct British intervention, with Perak appointing a British Resident. Following Perak's subsequent absorption into the Federated Malay States (FMS), the British reformed administration of the sultanate through a new style of government, actively promoting a market-driven economy and maintaining law and order while combatting the slavery widely practised across Perak at the time. The three-year Japanese occupation in World War II halted further progress. After the war, Perak became part of the temporary Malayan Union, before being absorbed into the Federation of Malaya. It gained full independence through the Federation, which subsequently became Malaysia on 16 September 1963.

Perak is ethnically, culturally and linguistically diverse. The state is known for several traditional dances: bubu, dabus, and labu sayong, the latter name also referring to Perak's unique traditional pottery. The head of state is the Sultan of Perak, and the head of government is the Menteri Besar. Government is closely modelled on the Westminster parliamentary system, with the state administration divided into administrative districts. Islam is the state religion, and other religions may be practised freely. Malay and English are recognised as the official languages of Perak. The economy is mainly based on services and manufacturing.

Etymology

There are many theories about the origin of the name Perak.[10][11] Although not used until after 1529, the most popular etymology is "silver" (in Malay: perak). This is associated with tin mining from the state's large mineral deposits, reflecting the Perak's position as one of the world's largest sources of tin.[10][12][13] The first Islamic kingdom established in the state was of the lineage of the Sultanate of Malacca.[13] Some local historians have suggested that Perak was named after Malacca's bendahara, Tun Perak.[10][14] In maps prior to 1561, the area is marked as Perat.[13] Other historians believe that the name Perak derives from the Malay phrase "kilatan ikan dalam air" (the glimmer of fish in water), which looks like silver.[10][11] Perak has been translated into Arabic as دار الرضوان (Dār al-Riḍwān), "abode of grace".[15]

History

Sultanate of Perak 1528–1895

Federated Malay States 1895–1942

Empire of Japan 1942–1945

Malayan Union 1946–1948

Federation of Malaya 1948–1963

Malaysia 1963–present

Prehistory

Among the prehistoric sites in Malaysia where artefacts from the Middle Palaeolithic era have been found are Bukit Bunuh, Bukit Gua Harimau, Bukit Jawa, Bukit Kepala Gajah, and Kota Tampan in the Lenggong Archaeological Heritage Valley.[16][17] Of these, Bukit Bunuh and Kota Tampan are ancient lakeside sites, the geology of Bukit Bunuh showing evidence of meteoric impact.[18] The 10,000-year-old skeleton known as Perak Man was found inside the Bukit Gunung Runtuh cave at Bukit Kepala Gajah.[19][20] Ancient tools discovered in the area of Kota Tampan, including anvils, cores, debitage, and hammerstones, provide information on the migrations of Homo sapiens.[18] Other important Neolithic sites in the country include Bukit Gua Harimau, Gua Badak, Gua Pondok, and Padang Rengas, containing evidence of human presence in the Mesolithic Hoabinhian era.[21][22]

.JPG.webp)

In 1959, a British artillery officer stationed at an inland army base during the Malayan Emergency discovered the Tambun rock art, identified by archaeologists as the largest rock art site in the Malay Peninsula. Most of the paintings are located high above the cave floor, at an elevation of 6–10 metres (20–33 ft).[24][25] Seashells and coral fragments scattered along the cave floor are evidence that the area was once underwater.[26]

The significant numbers of statues of Hindu deities and of the Buddha found in Bidor, Kuala Selensing, Jalong, and Pengkalan Pegoh indicate that, before the arrival of Islam, the inhabitants of Perak were mainly Hindu or Buddhist. The influence of Indian culture and beliefs on society and values in the Malay Peninsula from early times is believed to have culminated in the semi-legendary Gangga Negara kingdom.[22][27][28] The Malay Annals mention that Gangga Negara at one time fell under Siamese rule, before Raja Suran of Thailand sailed further south down the Malay Peninsula.[29]

Sultanate of Perak

By the 15th century, a kingdom named Beruas had come into existence. Inscriptions found on early tombstones of the period show a clear Islamic influence, believed to have originated from the Sultanate of Malacca, the east coast of the Malay Peninsula, and the rural areas of the Perak River.[22][30] The first organised local government systems to emerge in Perak were the Manjung government and several other governments in Central and Hulu Perak (Upper Perak) under Raja Roman and Tun Saban.[22] With the spread of Islam, a sultanate subsequently emerged in Perak; the second oldest Muslim kingdom in the Malay Peninsula after the neighbouring Kedah Sultanate.[31] Based on Salasilah Raja-Raja Perak (Perak Royal Genealogy), the Perak Sultanate was formed in the early 16th century on the banks of the Perak River by the eldest son of Mahmud Shah, the 8th Sultan of Malacca.[32][33][34] He ascended to the throne as Muzaffar Shah I, first sultan of Perak, after surviving the capture of Malacca by the Portuguese in 1511 and living quietly for a period in Siak on the island of Sumatra. He became sultan through the efforts of Tun Saban, a local leader and trader between Perak and Klang.[33] There had been no sultan in Perak when Tun Saban first arrived in the area from Kampar in Sumatra.[35] Most of the area's residents were traders from Malacca and Selangor, and from Siak, Kampar, and Jambi in Sumatra. Among them was an old woman, Tok Masuka from Daik, who raised a Temusai child named Nakhoda Kassim.[35] Before her death, she called on the ancestors of Sang Sapurba to take her place, to prevent the royal lineage from disappearing from the Malay Peninsula. Tun Saban and Nakhoda Kassim then travelled to Kampar, where Mahmud Shah agreed to their request and named his son the first Sultan of Perak.[35][36]

Perak's administration became more organised after the Sultanate was established. In democratic Malacca, government was based on the feudal system.[11] With the opening up of Perak in the 16th century, the state became a source of tin ore. It appears that anyone was free to trade in the commodity, although the tin trade did not attract significant attention until the 1610s.[37][38]

Throughout the 1570s, the Sultanate of Aceh subjected most parts of the Malay Peninsula to continual harassment.[33][39] The sudden disappearance of Perak's Sultan Mansur Shah I in mysterious circumstances in 1577 gave rise to rumours of abduction by Acehnese forces.[39] Soon afterwards, the late Sultan's widow and his 16 children were taken as captives to Sumatra.[33][39] Sultan Mansur Shah I's eldest son, Raja Alauddin Mansur Syah, married an Acehnese princess and subsequently became Sultan of Aceh. The Sultanate of Perak was left without a ruling monarch, and Perak nobles journeyed to Aceh in the same year to ask the new Sultan Alauddin for a successor.[33] The ruler sent his younger brother to become Perak's third monarch. Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin Shah ruled Perak for seven years, maintaining the unbroken lineage of the Malacca dynasty.[33] Although Perak did fall under the authority of the Acehnese Sultanate, it remained entirely independent of Siamese control for over two hundred years from 1612,[39][40] in contrast with its neighbour, Kedah, and many of the Malay sultanates in the northern part of the Malay Peninsula, which became tributary states of Siam.[41][42]

When Sultan Sallehuddin Riayat Shah died without an heir in 1635, a state of uncertainty prevailed in Perak. This was exacerbated by a deadly cholera epidemic that swept through the state, killing many royal family members.[33] Perak chieftains were left with no alternative but to turn to Aceh's Sultan Iskandar Thani, who sent his relative, Raja Sulong, to become the new Perak Sultan Muzaffar Shah II.

Aceh's influence on Perak began to wane when the Dutch East India Company (VOC) arrived, in the mid–17th century.[39] When Perak refused to enter into a contract with the VOC as its northern neighbours had done, a blockade of the Perak River halted the tin trade, causing suffering among Aceh's merchants.[43] In 1650, Aceh's Sultana Taj ul-Alam ordered Perak to sign an agreement with the VOC, on condition that the tin trade would be conducted exclusively with Aceh's merchants.[32][43][44][45] By the following year, 1651, the VOC had secured a monopoly over the tin trade, setting up a store in Perak.[46] Following long competition between Aceh and the VOC over Perak's tin trade,[47] on 15 December 1653, the two parties jointly signed a treaty with Perak granting the Dutch exclusive rights to tin extracted from mines located in the state.[33][48]

Although Perak nobles had destroyed the earlier store structure, on orders from the Dutch base in Batavia, a fort was built on Pangkor Island in 1670 as a warehouse to store tin ore mined in Perak.[46] This warehouse was also destroyed in further attacks in 1690, but was repaired when the Dutch returned with reinforcements.[46] In 1699, when the regional dominant Sultanate of Johor lost its last Malaccan dynasty sultan, Sultan Mahmud Shah II, Perak now had the sole claim of being the final heir of the old Sultanate of Malacca. However, Perak could not match the prestige and power of either the Malacca or Johor Sultanates.[49]

The early 18th century started with 40 years of civil war where rival princes were bolstered by local chiefs, the Bugis and Minang, all fighting for a share of tin revenues. The Bugis and several Perak chiefs were successful in ousting the Perak ruler, Sultan Muzaffar Riayat Shah III in 1743.[49] In 1747, Sultan Muzaffar Riayat Shah III, now only holding power in the area of Upper Perak, signed a treaty with Dutch Commissioner Ary Verbrugge under which Perak's ruler recognised the Dutch monopoly over the tin trade, agreed to sell all tin ore to Dutch traders, and allowed the Dutch to build a new warehouse fort on the Perak River estuary.[50] With construction of the new warehouse near the Perak River (also known as Sungai Perak), the old warehouse was abandoned permanently and left in ruins.[46] When repeated Burmese invasions resulted in the destruction and defeat of the Siamese Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1767 by the Burmese Konbaung dynasty, neighbouring Malay tributary states began to assert their independence from Siam.[51] To further develop Perak's tin mines, the Dutch administration suggested that its 17th Sultan, Alauddin Mansur Shah Iskandar Muda, should allow in Chinese miners. The sultan himself encouraged the scheme in 1776, requesting that additional Chinese workers be sent from Dutch Malacca.[52] The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War in 1780 adversely affected the tin trade in Perak, and many Chinese miners left.[53] In a move which angered the Siamese court, neighbouring Kedah's Sultan Abdullah Mukarram Shah then entered into an agreement with the English East India Company (EIC), ceding Penang Island to the British in 1786 in exchange for protection.[54][55][56]

.jpg.webp)

Siam regained strength under the Thonburi Kingdom, led by Taksin, after freeing itself from Burmese occupation. After repelling another large-scale Burmese invasion, the Rattanakosin Kingdom (Chakri dynasty) led by Rama I, as the successor of the Thonburi Kingdom, turned its attention to its insubordinate southern Malay subjects, fearing renewed attacks from Burma along the western seaboard of the Malay Peninsula.[41][58] Attention to the south was also needed because of disunity and rivalries among the various southern tributary sultanates, stemming from personal conflicts and a reluctance to submit to Siamese authority.[58] One example of this resistance was the Sultanate of Pattani under Sultan Muhammad, who refused to aid Siam during the Siamese war of liberation. This led Rama I's younger brother, Prince Surasi, to attack Pattani in 1786. Many Malays were killed, and survivors were taken to the Siamese stronghold in Bangkok as slaves.[42][51][59][60] Siam's subjugation of Pattani served as a direct warning to the other Malay tributary states, particularly Kedah, they too having been forced to provide thousands of men, and food supplies, throughout the Siamese resistance campaign against the Burmese.[42][61]

In 1795, the Dutch temporarily withdrew from Malacca for the duration of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe. Malacca's authority was transferred to the British Resident.[32][62] When war ended, the Dutch returned to administer Malacca in 1818.[63] In 1818, the Dutch monopoly over the tin trade in Perak was renewed, with the signing of a new recognition treaty.[64] The same year, when Perak refused to send a bunga mas tribute to the Siamese court, Rama II of Siam forced Kedah to attack Perak. The Sultanate of Kedah knew the intention behind the order was to weaken ties between fellow Malay states,[61][65][66] but complied, unable to resist Siam's further territorial expansion into inland Hulu Perak. Siam's tributary Malay state, the Kingdom of Reman, then illegally operated tin mines in Klian Intan, angering the Sultan of Perak and provoking a dispute that escalated into civil war. Reman, aided by Siam, succeeded in controlling several inland districts.[67] In 1821, Siam invaded and conquered the Sultanate of Kedah, angered by a breach of trust.[58][61][68] The exiled Sultan of Kedah turned to the British to help him regain his throne, despite Britain's policy of non-engagement in expensive minor wars in the Malay Peninsula at the time, which the EIC upheld through the Governor-General of India.[42][66] Siam's subsequent plan to extend its conquests to the southern territory of Perak[39][63][66] failed after Perak defeated the Siamese forces with the aid of mixed Bugis and Malay reinforcements from the Sultanate of Selangor.[39][42][65][68] As an expression of gratitude to Selangor for assisting it to defeat Siam, Perak authorised Raja Hasan of Selangor to collect taxes and revenue in its territory. This power, however, was soon misused, causing conflict between the two sultanates.[69][70]

British protectorate

Since the EIC's establishment of early British presence in Penang, the British had maintained another trading post in Singapore, avoiding involvement in the affairs of the nearby Malay sultanate states.[75] In 1822, the British authority in India sent British diplomat John Crawfurd to Siam to negotiate trade concessions and gather information with a view to restoring the Sultan of Kedah to the throne. The mission failed.[76] In 1823, the Sultanates of Perak and Selangor signed a joint agreement to block the Dutch tin monopoly in their territories.[64] EIC policy shifted with the First Anglo-Burmese War in 1824, Siam then becoming an important ally.[66]

Through its Governor, Robert Fullerton, Penang tried to convince the main EIC authority in India to continue helping the Sultan of Kedah to regain his throne.[77] Throughout 1824, Siam aimed to expand its control towards Perak and Selangor.[78] The dispute between the British and Dutch formally ceased when Dutch Malacca in the Malay Peninsula was exchanged with British Bencoolen in Sumatra, both parties agreeing to limit their sphere of influence through the signing of the 1824 Anglo-Dutch Treaty.[79] In July 1825, an initial negotiation was held between Siam, represented by tributary state the Kingdom of Ligor, and the EIC.[80] The King of Ligor promised that Siam would not send its armada to Perak and Selangor, so resolving the issue of its attacks. The British renounced any aspiration to conquer Perak or interfere in its administration, promising to prevent Raja Hasan of Selangor from making trouble in Perak, and to try to reconcile the differences between Selangor and Ligor.[80] A month later, in August 1825, Ibrahim Shah of the Sultanate of Selangor signed a friendship and peace treaty with the EIC, represented by John Anderson, ending the long feud between the governments of Selangor and Perak.[81] Under the treaty, Selangor gave assurances to the British that it would not interfere in the affairs of Perak; the border between Perak and Selangor was finalised; and Raja Hasan of Selangor was to be immediately exiled from Perak, paving the way for peace between the two Malay states and the resolution of the power struggle between the British and Siam.[81]

In 1826, the Kingdom of Ligor broke its promise and attempted to conquer Perak. A small British expeditionary force thwarted the attack. The Sultan of Perak then ceded to the British the area of Dindings and Pangkor (the two now constitute Manjung District) so that the British could suppress pirate activity along the Perak coast where it became part of the Straits Settlements.[56] The same year, the British and Siam concluded a new treaty. Under the Burney Treaty, signed by British Captain Henry Burney and the Siamese government, the British undertook not to intercede in the affairs of Kedah despite their friendly relations with Kedah's ruler, and the Siamese undertook not to attack either Perak or Selangor.[82][83]

The discovery of tin in Larut and rapid growth of the tin ore trade in the 19th century saw an increasing influx of Chinese labour. Later, rivalry developed between two Chinese secret societies. This, coupled with internal political strife between two faction of Perak's local Malay rulers, escalated into the Larut Wars in 1841.[84][85] After 21 years of liberation wars, neighbouring Kedah finally freed itself from full Siamese rule in 1843, although it remained a Siamese tributary state until 1909.[56][65] By 1867, the link between the Straits Settlements on the Malay coast and the British authority in India was broken, with separate administration and the transfer of the respective territories to the Colonial Office.[75] The Anglo-Dutch Treaties of 1870–71 enabled the Dutch to consolidate control over Aceh in Sumatra. This later escalated into the Aceh War.[86][87]

Internal conflicts ensued in Perak. In 1873, the ruler of one of Perak's two local Malay factions, Raja Abdullah Muhammad Shah II, wrote to the Governor of the British Straits Settlements, Andrew Clarke, requesting British assistance.[71] This resulted in the Treaty of Pangkor, signed on Pangkor Island on 20 January 1874, under which the British recognised Abdullah as the legitimate Sultan of Perak.[72] In return, the treaty provided for direct British intervention through the appointment of a Resident who would advise the sultan on all matters except religion and customs, and oversee revenue collection and general administration, including maintenance of peace and order.[88] The treaty marked the introduction of a British residential system, with Perak going on to become part of the Federated Malay States (FMS) in 1895. It was also a shift from the previous British policy of non-intervention in Perak's affairs.[56][71][72][73] James W. W. Birch was appointed as Perak's first British Resident. His inability to understand and communicate well with the locals, ignorance of Malay customs, and disparagement of the efforts of the Sultan and his dignitaries to implement British tax control and collection systems caused resentment. Local nationalist Maharaja Lela and the new monarch, Sultan Abdullah Muhammad Shah II, opposed him, and the following year, in 1875, Birch was assassinated through a conspiracy of local Malay dignitaries Seputum, Pandak Indut, Che Gondah, and Ngah Ahmad.[32][89] The assassination angered the British authority, and the perpetrators were arrested and executed. The Sultan and his chiefs, also suspected of involvement in the plot, were banished to the British Seychelles in the Indian Ocean in 1876.[90][91]

.jpg.webp)

During his exile, the Sultan had use of a government-owned residence at Union Vale in Victoria, Mahé. The other exiled chiefs were given allowances, but remained under strict surveillance. The Sultan and his chiefs were temporarily relocated to Félicité Island for five years, before being allowed to return to Victoria in 1882 when turmoil in Perak had subsided. The Sultan led a quiet life in the Seychellois community, and had communications access to Government House.[94] After many years, the Sultan was pardoned following petitioning by the Seychellois and correspondence between W. H. Hawley of Government House, Mauritius, and Secretary of State for the Colonies Henry Holland. He was allowed to return to the Malay Peninsula, and spent most of his later life in the Straits Settlements of Singapore and Penang before returning to Kuala Kangsar in Perak in 1922.[94][95]

British Resident in Perak Hugh Low proved an effective administrator, preferring to adopt a generous approach that avoided confrontation with local leaders. As a result, he was able to secure the co-operation of many rajas and village penghulu with his policy rather than resorting to force, despite giving transport infrastructure little attention during his term.[32][96][97] In 1882, Frank Swettenham succeeded Low for a second term as the Resident of Perak. During his mandate, Perak's rail and road infrastructure was put in place. Increasing numbers of labourers were brought from India, principally to work as railway and municipal coolies.[52][97]

The British introduced several changes to the local political structure, exerting influence on the appointment of the Sultan and restricting the power of his chiefs to Malay local matters. The Sultan and his chiefs were no longer entitled to collect taxes, but received a monthly allowance from the state treasury in compensation.[98] British intervention marked the beginning of Perak's transition from a primarily Malay society to a multi-ethnic population. The new style of government worked to promote a market-driven economy, maintain law and order, and combat slavery, seen by the British as an obstacle to economic development and incompatible with a capitalist economy.[98] Under the Anglo-Siamese Treaty, signed in Bangkok in 1909, Siam ceded to Great Britain its northern Malay tributary states of Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu and nearby islands. Exceptions were the Patani region, which remained under Siamese rule, and Perak, which regained the previously lost inland territory that became the Hulu Perak District.[67][74] The treaty terms stipulated that the British, through their government of the FMS, would assume responsibility for all debts owed to Siam by the four ceded Malay states, and relinquish British extraterritorial rights in Siam.[99]

Second World War

.jpg.webp)

There had been a Japanese community in Perak since 1893, managing the bus service between the town of Ipoh and Batu Gajah, and running brothels in Kinta.[52] There were a number of other Japanese-run businesses in Ipoh, including dentists, photo studios, laundries, tailors, barbers, and hotels. Activity increased as a result of the close relationship created by the Anglo-Japanese Alliance.[52]

Early in July 1941, before the beginning of World War II, a Ceylonese Malay policeman serving under the British administration in Perak raised an alert. A Japanese business owner living in the same building had told him that Japanese troops were on their way, approaching not around Singapore from the sea, as expected by the British, but from Kota Bharu in Kelantan, with bicycle infantry and rubber boats.[52] The policeman informed the British Chief Police Officer in Ipoh, but his claim was laughed off.[52] By 26 December 1941, the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) had arrived in Ipoh, the capital, moving southwards from Thailand. The following day they went on to Taiping, leaving destruction and heavy casualties in their wake.[100] The British forces, retreating from the north of the Malay Peninsula under Lieutenant-General Lewis Heath, had moved a further 80–100 miles (130–160 km) to the Perak River (Sungai Perak), damaging the route behind them to slow the Japanese advance.[100] With the approval of Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival, the British mounted a defensive stand near the river mouth and in Kampar, leaving the towns of Ipoh, Kuala Kangsar and Taiping unguarded.[100]

Most civil administrations were closed down, the European administrators and civilians evacuating to the south.[100] By mid-December, the Japanese had reached Kroh in the interior of Perak, moving in from Kota Bharu in Kelantan. The Japanese arrived both from the east and by boat along the western coast.[100] Within 16 days of their first landings, they had captured the entire northern part of the Malay Peninsula. The British were left trying to blockade the main road heading south from Ipoh. While the defending troops briefly slowed the Japanese at the Battle of Kampar and at the mouth of the Perak River, the Japanese advance along the trunk road, followed up with bombing and water-borne incursions, forced the British to retreat further south.[100][101]

The Japanese occupied all of Malaya and Singapore. Tokugawa Yoshichika, a scion of the Tokugawa clan whose ancestors were shōguns who ruled Japan from the 16th to 19th centuries, proposed a reform plan. Under its terms, the five kingdoms of Johor, Terengganu, Kelantan, Kedah-Penang, and Perlis would be restored and federated. Johor would control Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, and Malacca. An 800-square-mile (2,100 km2) area in southern Johor would be incorporated into Singapore for defence purposes.[102]

In the context of the military alliance between Japan and Thailand and their joint participation in the Burma campaign against the Allied forces, in 1943 the Empire of Japan restored to Thailand the former Malay tributary states of Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu, which had been ceded by the then-named Siam to the British under the 1909 treaty. These territories were then administered as Thailand's Four Malay States (Thai: สี่รัฐมาลัย), with Japanese troops maintaining an ongoing presence.[103][104] Perak suffered under harsh military control, restricted movement, and tight surveillance throughout the Japanese occupation and until 1945.[22][105] The press in occupied Malaya, including the English-language occupation-era newspaper The Perak Times, was entirely under the control of the Dōmei News Agency (Dōmei Tsushin), publishing Japanese-related war propaganda. The Dōmei News Agency also printed newspapers in Malay, Tamil, Chinese, and Japanese.[106] The indigenous Orang Asli stayed in the interior during the occupation. Much of their community was befriended by Malayan Communist Party guerrillas, who protected them from outsiders in return for information on the Japanese and their food supplies.[107] Strong resistance came mainly from the ethnic Chinese community, some Malays preferring to collaborate with the Japanese through the Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM) movement for Malayan independence. But Malay support also waned with increasingly harsh Japanese treatment of civilians during the occupation.[108] Two Chinese guerrilla organisations operated within Perak in northern Malaya. One, the Overseas Chinese Anti-Japanese Army (OCAJA), was aligned with the Kuomintang. The other, the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), was closely associated with the Chinese Communist Party. Although both opposed the Japanese, there were clashes between the two groups.[109]

Sybil Kathigasu, a Eurasian nurse and member of the Perak resistance, was tortured after the Japanese Kenpeitai military police discovered a clandestine shortwave radio set in her home.[110][111] John Davis, an officer of the British commando Force 136, part of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), trained local guerrillas prior to the Japanese invasion at the 101 Special Training School in Singapore, where he sought Chinese recruits for their commando teams.[112] Under the codename Operation Gustavus, Davis and five Chinese agents landed on the Perak coast north of Pangkor Island on 24 May 1943. They established a base camp in the Segari Hills, from which they moved to the plains to set up an intelligence network in the state.[112] In September 1943, they met and agreed to co-operate with the MPAJA, which then provided Force 136 with support and manpower. This first intelligence network collapsed, however, when many of its leaders, including Lim Bo Seng, were caught, tortured and killed by the Japanese Kenpeitai in June 1944.[112] On 16 December 1944, a second intelligence network, comprising five Malay SOE agents and two British liaison officers, Major Peter G. Dobree and Captain Clifford, was parachuted into Padang Cermin, near Temenggor Lake Dam in Hulu Perak under the codename Operation Hebrides. Its main objective was to set up wireless communications between Malaya and Force 136 headquarters in Kandy, British Ceylon, after the MPAJA's failure to do so.[104]

Post-war and independence

.JPG.webp)

Despite the Japanese surrender to the Allied forces in 1945, the Malay state had become unstable. This was exacerbated by the emergence of nationalism and a popular demand for independence as the British Military Administration took over from 1945 to 1946 to maintain peace and order, before the British began introducing new administrative systems under the Malayan Union.[22] The four neighbouring Malay states held by Thailand throughout the war were returned to the British. This was done under a proposal by the United States, offering Thailand admission to the United Nations (UN) and a substantial American aid package to support its economy after the war.[114][115] The MPAJA, under the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), had fought alongside the British against the Japanese, and most of its members received awards at the end of the war. However, party policy become radicalised under the authority of Perak-born Chin Peng, who took over the CPM administration following former leader Lai Teck's disappearance with the party funds.[116]

Under Chin's authority, the MPAJA killed those they considered to have been Japanese collaborators during the war, who were mainly Malays. This sparked racial conflict and Malay retaliation. Killer squads were also dispatched by the CPM to murder European plantation owners in Perak, and Kuomintang leaders in Johor. The Malayan government's subsequent declaration of a state of emergency on 18 June 1948 marked the start of the Malayan Emergency.[116][117] Perak and Johor became the main strongholds of the communist movement. In the early stages their actions were not co-ordinated, and the security forces were able to counter them.[118][119] Earlier in 1947, the head of the Perak's Criminal Investigation Department, H. J. Barnard, negotiated an arrangement with the Kuomintang-influenced OCAJA leader Leong Yew Koh. This resulted in most OCAJA members being absorbed into the national Special Constabulary, and fighting against the MPAJA's successor, the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA).[109]

The Kinta Valley, one of the richest tin mining areas in Malaya, accounted for most of the country's tin exports to the United States. To protect it from the communists, on 1 May 1952, the Perak Chinese Tin Mining Association established the Kinta Valley Home Guard (KVHG). Often described as a private Chinese Army, most of the KVHG's Chinese members had links to the Kuomintang.[120][121] Many of the Kuomintang guerrillas were absorbed from the Lenggong area, where there were also members of Chinese secret societies whose main purpose was to defend Chinese private property against the communists.[52] Throughout the first emergency the British authorities and their Malayan collaborators fought against the communists. This continued even after the proclamation of the independence of the Federation of Malaya, on 31 August 1957. As a result, most of the communist guerrillas were successfully pushed across the northern border into Thailand.[118]

Malaysia

In 1961, the Prime Minister of the Federation of Malaya, Tunku Abdul Rahman, sought to unite Malaya with the British colonies of North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore.[122] Despite growing opposition from the governments of both Indonesia and the Philippines, and from communist sympathisers and nationalists in Borneo, the Federation came into being on 16 September 1963.[123][124] The Indonesian government later initiated a "policy of confrontation" against the new state.[125] This prompted the British, and their allies Australia and New Zealand, to deploy armed forces, although no skirmishes arising from the Indonesian attacks occurred around Perak.[126][127] In 1968, a second communist insurgency occurred in the Malay Peninsula. This affected Perak mainly through attacks from Hulu Perak by the communist insurgents who had previously retreated to the Thai border.[128] The Perak State Information Office launched two types of psychological warfare to counter the increasing communist propaganda disseminated from the insurgents' hide-out. The campaign against the second insurgency had to be carried out as two separate efforts, because communist activities in Perak were split into two factions. One faction involved infiltrators from across the Thai border; the other was a communist group living among local inhabitants.[129]

With the end of British rule in Malaya and the subsequent formation of the Federation of Malaysia, new factories were built and many new suburbs developed in Perak. But there was also rising radicalism among local Malay Muslims, with increasing Islamisation initiated by several religious organisations, and by Islamic preachers and intellectuals who caught the interest both of Malay royalty and commoners.[130] Good relations with the country's rulers resulted in Islamic scholars being appointed as palace officers and dignitaries, teachers, and religious judges, contributing to the further spread of Islam. Islam is thus now seen as a major factor that shaped current attitudes to standing up for Malay rights.[131]

Geography

.jpg.webp)

Perak has a total land area of 20,976 square kilometres (8,099 sq mi), and is situated in the west of the Malay Peninsula on the Strait of Malacca.[1] Its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extends into the Strait.[132] It is the second largest Malaysian state on the Malay Peninsula, and the fourth largest in Malaysia.[133][134] The state has 230 kilometres (140 mi) of coastline, of which 140.2 kilometres (87.1 mi) are affected by coastal erosion.[135] Mangrove forests grow along most of Perak's coast, with the exception of Pangkor Island, with its rich flora and fauna, where several of the country's forest reserves are located.[136][137][138] There is extensive swampland along the coastal alluvial zones of the west coast between central Perak and southern Selangor.[139] Perak has an overall total forest cover of 1,027,404.31 hectares (2,538,771 acres), including 939,403.01 hectares (2,321,315 acres) of forest lands, 41,616.75 hectares (102,837 acres) of mangroves, and another 2,116.55 hectares (5,230 acres) of forest plantations.[140] A total of 995,284.96 hectares (2,459,403 acres) of forest has been gazetted by the state government as forest reserve, scattered across 68 areas throughout the state.[141] Perak's geology is characterised by eruptive masses, which form its hills and mountain ranges. The state is divided by three mountain chains into the three plains of Kinta, Larut and Perak, running parallel to the coast.[142] The Titiwangsa Range passes through Perak. Its highest point, the 2,183-metre (7,162 ft) Mount Korbu, is located in the district of Kinta near the border with the state of Kelantan.[143][144] Alluvium covers much of the plains, with detached masses of sedimentary rock appearing at rare intervals.[142]

An extensive network of rivers originates from the inland mountain ranges and hills.[32] Perak's borders with the states of Kedah, Penang and Selangor are marked by rivers, including the Bernam and Kerian Rivers.[145] Perak has 11 major river basins of more than 80 km (50 mi). Of these, the Perak River basin is the largest, with an area of 14,908 km2 (5,756 sq mi), about 70% of the total area of the state. It is the second largest river basin on the Malay Peninsula, after the Pahang River basin.[146] The Perak River is the longest river in the state, at some 400 km (250 mi), and is the Malay Peninsula's second longest after the Pahang River. It originates in the mountains of the Perak-Kelantan-Yala border, snaking down to the Strait of Malacca.[147][148][149] Other major rivers include the Beruas, Jarum Mas, Kurau, Larut, Manjung, Sangga Besar, Temerloh, and Tiram Rivers.[150]

Perak is located in a tropical region with a typically hot, humid and wet equatorial climate, and experiences significant rainfall throughout the year.[151] The temperature remains fairly constant, between 21 and 27 °C (70 and 81 °F). Humidity is often above 80%.[152][153] Annual rainfall is about 3,000 millimetres (120 in), the central area of the state receiving an average of 5,000 mm (200 in) of rain.[154][155] The state experiences two monsoon seasons: the northeast and southwest seasons. The northeast season occurs from November to March, the southwest from May to September, and the transitional months for the monsoon seasons are April and June. The northeast monsoon brings heavy rains, especially in the upper areas of Hulu Perak, causing floods.[156] Little effect of the southwest monsoon is felt in the Kinta Valley, although coastal areas of southern Perak occasionally experience thunderstorms, heavy rain and strong, gusting winds in the predawn and early morning.[157][158]

- Landscapes of Perak

Mount Korbu with surrounding vegetation

Mount Korbu with surrounding vegetation Mirror Lake in Ipoh

Mirror Lake in Ipoh Forest Brook in Tapah Hills

Forest Brook in Tapah Hills Twilight in Lumut Beach

Twilight in Lumut Beach

Biodiversity

The jungles of Perak are highly biodiverse. The state's main natural park, Royal Belum State Park, covers an area of 117,500 hectares (290,349 acres) in northern Perak. It contains 18 species of frog and toad, 67 species of snake, more than 132 species of beetle, 28 species of cicada, 97 species of moth, and 41 species of dragonfly and damselfly.[159] The park was further gazetted as National Heritage Site by the federal government in 2012, and was inscribed on the World Heritage Site tentative list of UNESCO in 2017.[160] Royal Belum State Park also hosts an estimated 304 bird species, including migratory species, in addition to birds endemic to the three forest reserve areas of Pangkor Island.[161][162] Ten hornbill species are found within the area, including large flocks of the plain-pouched hornbill. Mammal species include the Seladang, Asian elephant, and Malayan tiger. The area is also notable for harbouring high concentrations of at least three Rafflesia species.[163] The Pulau Sembilan (Nine Islands) State Park in western Perak covers an area of 214,800 hectares (530,782 acres).[164] Its coral reefs are home to coral reef fish species.[165] In addition, 173 freshwater fish species have been identified as native to the state.[166] Another natural attraction, the tin-mining ponds in Kinta District, was gazetted as a state park in 2016. The Kinta Nature Park, Perak's third state park, covers an area of 395.56 hectares (977 acres).[167][168]

_(8744026399).jpg.webp)

The government of Perak has stated its commitment to protecting its forests to ensure the survival of endangered wildlife species, and to protect biodiversity.[169] The Perak Forestry Department is the state body responsible for forest management and preservation.[170] In 2013, the state planted some 10.9 million trees under the "26 Million Tree Planting Campaign: One Citizen One Tree", associated with global Earth Day.[171]

Widespread conversion and reclamation of mangroves and mudflats for economic and residential purposes has caused the rapid decline of shore birds, 86% of the reduction on the Malay Peninsula having occurred on Perak's coasts.[172] Poaching in forest reserve areas has caused a stark decline in mammal populations. The Perak State Park Corporation estimates that there were only 23 Malayan tigers left within the state's two forest reserves of Royal Belum and Temenggor in 2019.[173] The state government of Perak has also been blamed in part for destroying forest reserves for the lucrative wood and palm oil businesses. Records since 2009 reveal that more than 9,000 hectares (22,239 acres) of permanent forest reserves have been degazetted in the state, the latest occurring within the Bikam Permanent Forest Reserve in July 2013.[174] A number of business activities permitted by the state government have caused environmental damage, including to many of Perak's rivers, which require extensive water treatment because of severe pollution.[175][176][177] Between 1982 and 1994, the state government was embroiled in a radioactive environmental pollution controversy over the deaths of seven residents who suffered from birth defects and leukaemia resulting from exposure. The factory involved was only closed and cleaned up following lengthy court action by affected residents and increasing international pressure. No responsibility has been accepted by the associated companies, the state government, or the federal government.[178][179] Although Perak has the highest number of mangrove reserves of the Malay Peninsula states, with 19 reserves in the mangroves of Matang,[180] growing uncontrolled clearance of mangroves for aquaculture projects and residential areas is causing significant coastal erosion in addition to the damage resulting from climate change.[175]

Politics

Government

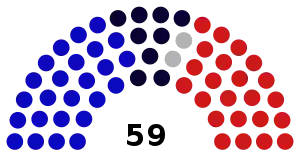

| |||||

| Affiliation | Coalition/Party Leader | Status | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 election | Current | ||||

| Perikatan Nasional | Saarani Mohammad | Government | 30 | 35 | |

| Pakatan Harapan | Abdul Aziz Bari | Opposition | 29 | 24 | |

| Total | 59 | 59 | |||

| Government majority | 2 | 11 | |||

Perak is a constitutional monarchy, with a ruler elected by an electoral college composed of the major chiefs.[181] The Sultan is the constitutional head of Perak. The current Sultan of Perak is Nazrin Shah, who acceded to the throne on 29 May 2014.[182] The main royal palace is the Iskandariah Palace in Kuala Kangsar. Kinta Palace in Ipoh is used by the sultan as an occasional residence during official visits.[183][184] Other palaces in Ipoh include the Al-Ridhuan Palace, Cempaka Sari Palace, and Firuz Palace.[184]

The state government is headed by a Menteri Besar (Chief Minister), assisted by an 11-member Executive Council (Exco) selected from the members of the Perak State Legislative Assembly.[185] The 59-seat Assembly is the legislative branch of Perak's government, responsible for making laws in matters regarding the state. It is based on the Westminster system. Members of the Assembly are elected by citizens every five years by universal suffrage. The Chief Minister is appointed on the basis of his or her ability to command a majority in the Assembly. The majority (35 seats) is currently held by Perikatan Nasional (PN) 13 days after Pakatan Harapan government collapse.

Prior to the major British overhaul of Perak's administration, slavery was widely practised along with a type of corvée labour system, called kerah. The chief of a given area could call on his citizens to work as forced labour without pay, although under normal circumstances food was still provided.[98][186] The system was created to ensure the maintenance of the ruling class. It was often described as onerous and demanding, as there were times when the call to duty, and its duration, interfered with citizens' individual work.[186] The slaves were divided into two classes: debtor-bondsmen and ordinary slaves. The debtor-bondsmen had the higher status, being ranked as free men and acknowledged as members of their masters' society. In contrast, the ordinary slaves had no prospect of status redemption. As Islam does not allow enslavement of fellow Muslims, the ordinary slaves came mainly from non-Muslim groups, especially the Orang Asli, Batak, and Africans purchased by Malays on pilgrimage in Mecca.[107][186]

State administration issues and subsequent 2009 constitutional crisis

The opposition Pakatan Rakyat (PR) coalition won Perak in the 2008 general election. Although the Democratic Action Party (DAP) had won the most seats of the opposition parties, Mohammad Nizar Jamaluddin of the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) was appointed Menteri Besar of the state.[187] This happened because the state constitution states that the Menteri Besar must be a Muslim, unless the Sultan specially appoints a non-Muslim to the office.[188][189] As the DAP did not have any Muslim assemblymen in Perak at that time, the Menteri Besar had to come from one of its two allied parties, the People's Justice Party (PKR) or the PAS.[188] However, the national ruling party, Barisan Nasional (BN), gained control over the state government administration when three PR assemblymen, Hee Yit Foong (Jelapang), Jamaluddin Mohd Radzi (Behrang), and Mohd Osman Mohd Jailu (Changkat Jering) defected to the BN as independent assemblymen during the crisis, on 3 February 2009.[190][191] A statement from the office of the Sultan of Perak urged the PR Menteri Besar to resign, but also refused to dissolve the State Legislative Assembly, which would have triggered new elections.[192] Amid multiple protests, lawsuits and arrests, a new BN-led Assembly was sworn in on 7 May. The takeover was then ruled illegal by the High Court in Kuala Lumpur, on 11 May 2009, restoring power to the PR.[193][194] The following day, the Court of Appeal of Malaysia suspended the High Court ruling pending a new Court of Appeal judgment. On 22 May 2009, the Court of Appeal overturned the High Court's decision and returned power to the BN. Many opposition party supporters believed that the crisis was effectively a "power grab", in which the democratically elected government was ousted through the political machinations of the more dominant national ruling party.[194][195]

Departments

- Perak State Finance Office[196]

- Perak Irrigation and Drainage Department[197]

- Perak State Forestry Department[198]

- Perak Social Welfare Department[199]

- Perak Syariah Judiciary Department[200]

- Perak Public Works Department[201]

- Perak State Islamic Religious Affairs Department[202]

- Perak Public Service Commission[203]

- Perak State Agriculture Department[204]

- Office of Lands and Mines Perak[205]

- Perak State Mufti Office[206]

- Perak Town and Country Planning Department[207]

- Department of Veterinary Services of Perak[208]

Statutory bodies

Administrative divisions

Perak is divided into 12 districts (daerah), 81 mukims, and 15 local governments.[211][212] There are district officers for each district and a village headperson (ketua kampung or penghulu) for each village in the district. Before the British arrived, Perak was run by a group of relatives and friends of the Sultan who held rights to collect taxes and duties.[98] The British developed a more organised administration following Perak's integration into the Federated Malay States (FMS). The FMS government created two institutions, the State Council and the Malay Administrative Service (MAS).[98] The two institutions encouraged direct Malay participation and gave the former ruling class a place in the new administrative structure. Most of the Sultan's district chiefs removed from authority at that time were given new positions in the State Council, although their influence was restricted to Malay social matters raised in council business. The Sultan and the district chiefs were compensated for their loss of tax revenue with a monthly allowance from the state treasury.[98]

The role of the local penghulus changed considerably when they were appointed no longer by the Sultan but by the British Resident.[213] Colonial land policy introduced individual landholding, thereby making land a commodity, and the penghulu were then involved in matters relating to this property.[98] The Perak State Council was established in 1875 to assist the British Resident in most administrative matters. It also brought together the Malay chiefs and Chinese leaders (Kapitan Cina) to deal with certain administrative issues relating to Perak's growing Malay and Chinese populations.[98] The State Council also helped provide education and training to assist Malays in qualifying for government positions. When the post of the FMS Resident was abolished, other European-held administrative posts were gradually occupied by local appointees. As in the rest of Malaysia, local government comes under the purview of state government.[98]

| Administrative divisions of Perak | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp)

ɢᴇʀɪᴋ

ᴘᴀʀɪᴛ ʙᴜɴᴛᴀʀ

ᴛᴀɪᴘɪɴɢ

ᴋᴜᴀʟᴀ ᴋᴀɴɢsᴀʀ

ɪᴘᴏʜ

ʙᴀᴛᴜ ɢᴀᴊᴀʜ

sᴇʀɪ ɪsᴋᴀɴᴅᴀʀ

ᴋᴀᴍᴘᴀʀ

ᴛᴀᴘᴀʜ

sᴇʀɪ ᴍᴀɴᴊᴜɴɢ

ᴛᴇʟᴜᴋ ɪɴᴛᴀɴ

ʙᴀɢᴀɴ ᴅᴀᴛᴜᴋ

ᴛᴀɴᴊᴜɴɢ ᴍᴀʟɪᴍ

| ||||||

| UPI code[211] | Districts | Population (2010 census)[2] |

Area (km2)[214] |

Seat | Mukims | |

| 0801 | Batang Padang | 123,600 | 1,794.18 | Tapah | 4 | |

| 0802 | Manjung | 227,071 | 1,113.58 | Seri Manjung | 5 | |

| 0803 | Kinta | 749,474 | 1,305 | Batu Gajah | 5 | |

| 0804 | Kerian | 176,975 | 921.47 | Parit Buntar | 8 | |

| 0805 | Kuala Kangsar | 155,592 | 2,563.61 | Kuala Kangsar | 9 | |

| 0806 | Larut, Matang and Selama | 326,476 | 2,112.61 | Taiping | 14 | |

| 0807 | Hilir Perak | 128,179 | 792.07 | Teluk Intan | 5 | |

| 0808 | Hulu Perak | 89,926 | 6,560.43 | Gerik | 10 | |

| 0809 | Selama | — | — | — | 3 | |

| 0810 | Perak Tengah | 99,854 | 1,279.46 | Seri Iskandar | 12 | |

| 0811 | Kampar | 96,303 | 669.8 | Kampar | 2 | |

| 0812 | Muallim | 69,639 | 934.35 | Tanjung Malim | 3 | |

| 0813 | Bagan Datuk | 70,300 | 951.52 | Bagan Datuk | 4 | |

| Note: Population data for Hilir Perak, Bagan Datuk, Batang Padang, and Muallim are based on district land office data. Selama is an autonomous sub-district (daerah kecil) under Larut, Matang and Selama.[215] Most districts and sub-districts have a single local government, excepting Hulu Perak and Kinta, respectively divided into three (Gerik, Lenggong and Pengkalan Hulu), and two (Batu Gajah and Ipoh) local councils. Bagan Datuk remains under the jurisdiction of Teluk Intan council. | ||||||

On 26 November 2015, it was announced that the Batang Padang District sub-district of Tanjung Malim would become Perak's 11th district, to be called Muallim.[216][217] Sultan Nazrin officiated at its formal creation on 11 January 2016.[218] On 9 January 2017, the Sultan proclaimed Bagan Datuk the 12th district of the state.[219] The proclamation marked the start of transformation for the district, one of the biggest coconut producers in Malaysia.[220][221]

Economy

Perak GDP Share by Sector (2016)[222]

From the 1980s on, Perak began an economic transition away from the primary sector, where for decades income was generated by the tin mining industry.[223][224] Early in 2006, the state government established the Perak Investment Management Centre (InvestPerak) to serve as the contact point for investors in the manufacturing and services sectors.[225] The state's economy today relies mainly on the tertiary sector.[226] In 2017, the tourism industry contributed RM201.4 billion (14.9%) to the state gross domestic product (GDP).[227]

Through the Eleventh Malaysia Plan (11MP), the state has set targets under its five-year 2016–2020 development plan, including economic development corridor targets for Southern Perak.[228] Perak has several development corridors, with a different focus for each district.[229] A 20-year masterplan was also formulated in 2017 to drive economic development in the state, with a development value of up to RM30 billion.[230]

In the first quarter of 2018, the state received a total of RM249.8 million in investments. A year later, investments in the first quarter of 2019 had increased to RM1.43 billion. Perak ranks fifth after Penang, Kedah, Johor and Selangor in total value of investments.[231] In 2018, investments of RM1.9 billion were planned for the implementation of a range of manufacturing projects and associated factory construction from 2019.[232]

Since 2005, Perak has made efforts to remain the biggest agricultural producer in Malaysia.[233] In 2008, the state sought to legalise the prawn-farming industry, mostly located in western Perak with some activity in Tanjung Tualang.[234][235][236] In 2016, some 17,589 young people in Perak were involved in implementing a range of state initiatives in Perak's agriculture sector.[237] In 2019, the Perak State Agriculture Development Corporation (SADC) launched the Perak AgroValley Project to increase the state's agricultural production. This initiative covers an area of 1,983.68 hectares (4,902 acres) in the Bukit Sapi Mukim Lenggong region.[238][239] Most of Perak's abandoned tin mine lakes provide suitable environments for the breeding of freshwater fish. 65% of abandoned mines have been used for fisheries production, with 30% of the fish exported to neighbouring Singapore and Indonesia.[240] To further improve agricultural productivity and meet increasing demand, the state plans to expand the permanent cultivation of vegetables, flowers, coconut, palm oil, durian, and mango, in different areas throughout Perak.[241] The construction sector accounted for 5.6% of Perak's economic growth in 2015, dropping to 4.0% the following year. Development and housing projects represented the sector's major contribution to the state's economic growth.[242]

Tourism

The tertiary sector is Perak's main economic sector. In 2018, the state was the second most popular destination for domestic tourists in Malaysia, after the state of Pahang.[243] Perak's attractions include the royal town of Kuala Kangsar and its iconic buildings, such as the Iskandariah Palace, Pavilion Square Tower, Perak Royal Museum, Sultan Azlan Shah Gallery, and Ubudiah Mosque.[244][245][246] The British colonial legacy in Perak includes the Birch Memorial Clock Tower, Ipoh High Court, Ipoh railway station, Ipoh Town Hall and Old Post Office, Kellie's Castle, Majestic Station Hotel, Malay College Kuala Kangsar, Maxwell Hill (Bukit Larut), Perak State Museum,[247] Royal Ipoh Club, St. John Church, and Taiping Lake Gardens.[248] The historical events of the local Malay struggle are remembered in the Pasir Salak Historical Complex.[249][250] There are also several historical ethnic Chinese landmarks, mainly in Ipoh, the capital. They include the Darul Ridzuan Museum building,[251] a former wealthy Chinese tin miner's mansion; Han Chin Pet Soo, a former club for Hakka miners and haven of shadowy activities;[248] and the Leaning Tower of Teluk Intan.[252]

The state also contains a number of natural attractions, including bird sanctuaries, caves, forest reserves, islands, limestone cliffs, mountains, and white sandy beaches. Among the natural sites are Banding Island, Belum-Temengor Forest Reserve,[253] Kek Lok Tong Cave Temple and Zen Gardens,[254] Kinta Nature Park,[254] Matang Mangrove Forest Reserve, Mount Yong Belar,[254] Pangkor Island,[255] Tempurung Cave,[256] and Ulu Kinta Forest Reserve.[254] Recreational attractions include the Banjaran Hotsprings Retreat,[257] D. R Seenivasagam Recreational Park,[258] Gaharu Tea Valley Gopeng,[259] Go Chin Pomelo Nature Park,[260] Gunung Lang Recreational Park,[254] Kinta Riverfront Walk,[257] Kuala Woh Jungle Park,[257] Lang Mountain,[257] Lost World of Tambun,[261] My Gopeng Resort,[257] Perak Herbal Garden,[257] Sultan Abdul Aziz Recreational Park, and Sungai Klah Hot Spring Park.[258]

Infrastructure

Perak has a 2016–2020 state government development plan. A Development Fund amounting to RM397,438,000 was approved by the State Legislative Assembly in 2016.[263] The 2018 Budget allocated Perak a further RM1.176 billion, of which RM421.28 million was earmarked for development expenditure, and RM755.59 million for management costs.[264][265] In addition to attracting investors, the state government is working to improve and build new infrastructure. The new government elected in 2018 announced its intention to continue development projects initiated by the previous government for all districts in Perak.[266]

Energy and water resources

Electricity distribution in Perak is operated and managed by the Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB). The Temenggor Power Station in Gerik has a capacity of 348 MW, the largest of the many hydroelectric plants in the state. Built by the British, Chenderoh Power Station, the state's oldest hydroelectric dam power station, has a capacity of 40.5 MW.[267] Other hydroelectric power stations include the Sultan Azlan Shah Kenering Power Station (120 MW), Sultan Azlan Shah Bersia Hydroelectric Power Station (72 MW), Sungai Piah Lower Power Station (54 MW), and Sungai Piah Upper Power Station (14.6 MW).[268][269] The 4,100 MW Manjung Power Plant, also known as the Sultan Azlan Shah Power Station, is a coal-fired power station located on an artificial island off the Perak coast. It is owned and operated by TNB Janamanjung, a wholly owned subsidiary of the TNB. The plant is considered one of the biggest Independent Power Producer (IPP) projects in Asia.[270] The GB3 combined cycle power plant in Lumut, operated by Malakoff, has a capacity of 640 MW.[271]

The state's piped water supply is managed by the Perak Water Board (PWB), a corporate body established under the Perak Water Board Enactment in 1988. It serves over 2.5 million people, and is among the biggest water operators on the Malay Peninsula, after Selangor and Johor. Before the PWB was established, water services were initially provided by the Perak Public Works Department, and subsequently by the Perak Water Supply Department.[272] The state's water supplies mainly come from its two major dams, the Air Kuning Dam in Taiping and the Sultan Azlan Shah Dam in Ipoh.[273]

Telecommunications and broadcasting

Telecommunications in Perak was originally administered by the Posts and Telecommunication Department, and maintained by the British Cable & Wireless Communications, responsible for all telecommunication services in Malaya.[274][275] The first telegraph line, connecting the British Resident's Perak House in Kuala Kangsar to the house of the Deputy British Resident at Taiping, was laid by the Department of Posts and Telegraph in 1874.[276] Further lines were then built to link all of the key British economic areas of the time, and in particular the British Straits Settlements territory.[277][278] Following the foundation of the Federation of Malaysia in 1963, in 1968 the telecommunications departments in Malaya and Borneo merged to form the Telecommunications Department Malaysia, which later became Telekom Malaysia (TM).[275] The state remains committed to full co-operation with the federal government to implement the latest telecommunications development projects in Perak.[279]

Perak is set to become the first Malaysian state to introduce the National Fiberisation and Connectivity Plan (NFCP) for high-speed Internet in rural areas.[280] Television broadcasting in the state is divided into terrestrial and satellite television. There are two types of free-to-air television providers: MYTV Broadcasting (digital terrestrial) and Astro NJOI (satellite), while IPTV is accessed via Unifi TV through the UniFi fibre optic internet subscription service.[281][282] The Malaysian federal government operates one state radio channel, Perak FM.[283]

Transport

_03_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Malaysia's North–South Expressway connects Perak with the other west coast Malaysian states and federal territories. Perak has two categories of road, as at 2016 totalling 1,516 kilometres (942 mi) of federal roads, and 28,767 kilometres (17,875 mi) of state roads.[284] A new highway, the West Coast Expressway, is being built to link the coastal areas of the state and reduce the growing traffic congestion.[285] Perak has a dual carriageway road network, and follows the left-hand traffic rule. Towns provide public transport, including buses, taxis, and Grab services. Under the Eleventh Malaysia Plan (11MP), around 23 infrastructure projects, worth RM4.7 billion, have been implemented. These include 11 road projects for the state, involving allocations of RM1.84 billion for upgrade and expansion works carried out by the Public Works Department (PWD).[286]

Ipoh railway station, on Jalan Panglima Bukit Gantang Wahab in the state capital, is the oldest station of Perak's rail network. It was built by the British in 1917, and upgraded in 1936.[287][288] In 2019, an integrated development project was launched to upgrade the railway station and its surrounding areas.[289] Boat services provide the main transport access to Pangkor Island, in addition to air travel.[290] Sultan Azlan Shah Airport is Perak's main international airport, acting as the main gateway to the state. Other public airports include Pangkor Airport and Sitiawan Airport, and there are private or restricted airfields such as Jendarata Airport and the military Taiping Airport.[291]

Healthcare

Health services in Perak are administered by the Perak State Health Department (Malay: Jabatan Kesihatan Negeri Perak). The state's main government hospital is the 990-bed Raja Permaisuri Bainun Hospital, previously known as the Ipoh Hospital, which also incorporates the women's and children's hospital.[292] Other hospitals include four specialist hospitals: Taiping Hospital, Teluk Intan Hospital, Seri Manjung Hospital, and the minor speciality Slim River Hospital; nine district hospitals: Batu Gajah Hospital, Changkat Hospital, Gerik Hospital, Kampar Hospital, Kuala Kangsar Hospital, Parit Buntar Hospital, Selama Hospital, Sungai Siput Hospital, Tapah Hospital; and one psychiatric hospital: Bahagia Ulu Kinta Hospital.[293] Other public health clinics, 1Malaysia clinics, and rural clinics are scattered throughout the state. There are a number of private hospitals, including the Anson Bay Medical Centre, Apollo Medical Centre, Ar-Ridzuan Medical Centre, Colombia Asia Hospital, Fatimah Hospital, Ipoh Pantai Hospital, Ipoh Specialist Centre, Kinta Medical Centre, Manjung Pantai Hospital, Perak Community Specialist Hospital, Sri Manjung Specialist Hospital, Taiping Medical Centre, and Ulu Bernam Jenderata Group Hospital.[294] In 2009, the state's doctor–patient ratio was 3 per 1,000.[295]

Education

All primary and secondary schools are within the jurisdiction of the Perak State Education Department, under the guidance of the national Ministry of Education.[297] Among the oldest schools in Perak are the King Edward VII School (1883), the Anglo-Chinese School (1895), and St. Michael's Institution (1912).[298] As of 2019, Perak had a total of 250 government secondary schools,[299] six international schools (City Harbour International School,[300] Fairview International School Ipoh Campus,[301] Imperial International School Ipoh,[302] Seri Botani International School,[303] Tenby Schools Ipoh,[304] and the Westlake International School),[305] and nine Chinese independent schools.[306] There is one Japanese learning centre, located in the state capital, Ipoh.[307] Sultan Idris Education University is the sole public university, and there are three private universities: the Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR), Quest International University,[308] and Universiti Teknologi Petronas, as well as the campus branch of the University of Kuala Lumpur Malaysian Institute of Marine Engineering Technology (UniKL MIMET),[309] and the University of Kuala Lumpur Royal College of Medicine Perak (UniKL RCMP).[310][311] Other colleges include the Cosmopoint College, Maxwell College Ipoh, Olympia College Ipoh, Sunway College Ipoh, Syuen College, Taj College, Tunku Abdul Rahman College Perak Branch Campus, and WIT College Ipoh Branch. There are several polytechnics, including the Sultan Azlan Shah Polytechnic in Behrang, and Ungku Omar Polytechnic in Ipoh.[312][313]

Demography

Ethnicity and immigration

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 1,569,139 | — |

| 1980 | 1,743,655 | +11.1% |

| 1991 | 1,877,471 | +7.7% |

| 2000 | 1,973,368 | +5.1% |

| 2010 | 2,299,582 | +16.5% |

| 2020 | 2,496,041 | +8.5% |

| Source: [314] | ||

The 2015 Malaysian Census reported the population of Perak at 2,477,700, making it the fifth most populous state in Malaysia, with a non-citizen population of 74,200.[315] Of the Malaysian residents, 1,314,400 (53.0%) are Malay, 713,000 (28.0%) are Chinese, 293,300 (11.0%) are Indian, and another 72,300 (2.9%) identified as other bumiputera.[315] In 2010, the population was estimated to be around 2,299,582, with 1,212,700 (52.0%) Malay, 675,517 (29.0%) Chinese, 274,631 (11.0%) Indian, and another 62,877 (2.7%) from other bumiputera.[2] Once the most populous state during the British administration under the FMS, Perak has yet to recover from the decline of the tin-mining industry.[186][316] The associated economic downturn resulted in a massive manpower drain to higher-growth states such as Penang, Selangor, and Kuala Lumpur.[317][318]

Perak's highest population density is mainly concentrated in the coastal and lowland areas. The Chinese and Indian population represents a higher percentage of the state's total population than in the neighbouring northern Malay states.[319] The presence of these groups was particularly significant after the British opened many tin mines and extensive rubber plantations in the mid-19th century. More than half of Perak's inhabitants in the 1930s were Chinese immigrants.[320] Perak's Indian community is mostly of Tamil ethnicity, although it also includes other South Indian communities such as the Malayalees, principally in Sitiawan, Sungai Siput, Trolak and Kuala Kangsar; the Telugus, in Teluk Intan and Bagan Datuk; and the Sikhs, scattered in and around Perak, predominantly in Ipoh and Tanjung Tualang.[321][322]

Population density is relatively low in much of Perak's interior, where the indigenous Orang Asli are scattered, including in the northernmost border district of Hulu Perak.[319] The indigenous people originally inhabited most of Perak's coastal areas, but were pushed deeper into the interior with the arrival of increasing numbers of Javanese, Banjar, Mandailing, Rawa, Batak, Kampar, Bugis and Minangkabau immigrants in the early 19th century. The Orang Asli oral traditions preserve stories of Rawa and Batak atrocities and enslavement of the aboriginal population.[107]

The current constitution defines Malays as someone who is Muslim and assimilated with Malay community Traditionally, the natives Malay mostly live in Lenggong, Gerik, Kinta, Bota and Beruas while the Javanese mostly lived in Hilir Perak, comprising Bagan Datuk, Batak Rabit, Sungai Manik, Teluk Intan, and a few other places along the Perak shores. The Mandailing and Rawa people were mostly in Gopeng, Kampar, Tanjung Malim, and Kampung Mandailing at Gua Balak. These people had mostly come from neighbouring Selangor, escaping the Klang War. The Buginese are found in Kuala Kangsar, especially in Kota Lama Kiri and Sayong. The few Minangkabau people in the state lived among the other ethnic groups with no distinct villages or settlements of their own. As of 2015, there were some 3,200 Malaysian Siamese in Perak, a legacy of the Siamese presence in the northern Malay states.[323] There is also a scattered Acehnese presence, dating back to the rule of the Sultanate of Aceh.

Religion

As in the rest of Malaysia, Islam is recognised as the state religion, although other religions may be freely practised.[325][326] According to the 2010 Malaysian Census, Perak's population was 55.3% Muslim, 25.4% Buddhist, 10.9% Hindu, 4.3% Christian, 1.7% Taoist or followers of Chinese folk religion, 0.8% other religions or unknown, and 0.9% non-religious.[324] The census indicated that 83.7% of Perak's Chinese population identified as Buddhist, with significant minorities identifying as Christian (9.2%), Chinese folk religion adherents (5.8%), and Muslim (0.2%). The majority of the Indian population identified as Hindu (87.6%), with significant minorities identifying as Christian (6.01%), Muslim (2.67%), and Buddhist (1.0%). The non-Malay bumiputera community was predominantly irreligion (28.2%), with significant minorities identifying as Muslim (24.1%), and Christian (22.9%). Among the majority population, all Malay bumiputera identified as Muslim. Article 160 of the Constitution of Malaysia defines professing the Islamic faith as one of the criteria of being a Malay.[324][327]

Languages

.jpg.webp)

As a multi-ethnic state, Perak is also linguistically diverse. The main Malay language dialect, Perak Malay, is characterised by its "e" (as in "red", [e]) and its "r", like the French "r" ([ʁ]). It is commonly spoken in central Perak, more specifically in the districts of Kuala Kangsar and Perak Tengah.[328][329] Speakers of the northern Kedah Malay dialect are also found in the northern part of Perak, comprising Kerian, Pangkor Island, and Larut, Matang and Selama districts.[330] In the northeastern part of Perak (Hulu Perak), and some parts of Selama and Kerian, the Malay people speak another distinct Malay language variant known as Basa Ulu/Grik (named after Grik), which is most closely related to Kelantan-Pattani Malay in Kelantan and southern Thailand (Yawi) due to geographical proximity and historical assimilation.[329] In the southern parts of Perak (Hilir Perak and Batang Padang), and also in the districts of Kampar and Kinta and several parts of Manjung, the dialect spoken is heavily influenced by the southern Malay dialects of the peninsula such as Selangor, Malacca, and Johore-Riau Malay. It is also influenced by several languages of the Indonesian archipelago: Javanese, Banjar, Rawa (a variety of Minangkabau), Batak (Mandailing), and Buginese, as a result of historical immigration, civil wars such as the Klang War, and other factors.[329]

Among Perak's various Chinese ethnicities, Malaysian Cantonese has become the lingua franca, although a number of dialects are spoken including Cantonese, Hakka, Mandarin, Teochew, Hokkien, and Hokchiu.[322][331][332]

The Tamil community mainly speaks a Malaysian dialect of the Tamil language; the Malayalees speak Malayalam; the Telugus speak the Telugu language; and the Sikhs speak Punjabi.[322] Over time, Tamil became a lingua franca among Perak's different Indian communities as Tamil-speaking people became the majority in several west coast Malaysian states with higher Indian populations.[320][322] A small number of Sinhala speakers also found in parts of the state capital, Ipoh.[322]

Several Orang Asli languages are spoken within the state, all belonging to the Aslian branch of the Austroasiatic languages. These languages are Lanoh, Temiar, Jahai, Kensiu, Kintaq, and Semai.

Members of the Siamese community mainly speak a Southern Thai variant, and are fluent in Malay, also having some knowledge of some of the Chinese dialects. With the multi-ethnic make-up of Perak's society, some people speak more than one language.[333][334]

Culture

Perak's multicultural society reflects the influences of different ethnicities throughout its history. Several Malay art forms, such as embroidery and performances like dabus, show apparent Arab cultural influence. The state's characteristic embroidery, tekat emas (gold embroidery), was once presented to royalty. Designs are based on floral, animal, and geometric motifs.[336] Dabus has existed for some 300 years, and is inseparable from a ritual involving incantation.[337] It was brought to Perak by traders from Sumatra, and practised by the Malay community in Lumut, Pasir Panjang Laut Village in Sitiawan, and Teluk Intan.[338] The traditional Malay pottery handicraft called labu sayong is part of the art heritage of Kuala Kangsar. Its unique design is uninfluenced by foreign techniques.[335] Labu sayong is associated with a dance called the sayong.[339] Another dance local to the Malays of Perak is the bubu, known for 120 years, which originates from Tanjung Bidara Village on Tiga Parit Island.[340]

Cantonese opera once flourished in the town of Ipoh, as the majority of Chinese there were Cantonese.[341][342][343] The history of China, and particularly Hong Kong, is recreated in Qing Xin Ling Leisure and Cultural Village (nicknamed Little Guilin) in Ipoh, with painted wooden structures around a lake set among limestone hills and caves.[344][345] Another ethnic Chinese cultural location in Perak is Bercham, originally called Wo Tau Kok in Cantonese in the 1950s. The area was formerly a tin mining centre, which also become one of the relocation points for Malayan ethnic Chinese during the British era under the government's Briggs Plan to protect and distance them from communist influence.[346][347] Perak's Malay, Chinese, and Indian communities, representing its three main ethnic groups, each have their own traditional arts and dance associations to maintain and preserve their respective cultural heritage.[348]

Cuisine