Merina Kingdom

The Merina Kingdom, or Kingdom of Madagascar, officially the Kingdom of Imerina (c. 1540–1897), was a pre-colonial state off the coast of Southeast Africa that, by the 19th century, dominated most of what is now Madagascar. It spread outward from Imerina, the Central Highlands region primarily inhabited by the Merina ethnic group with a spiritual capital at Ambohimanga and a political capital 24 km (15 mi) west at Antananarivo, currently the seat of government for the modern state of Madagascar. The Merina kings and queens who ruled over greater Madagascar in the 19th century were the descendants of a long line of hereditary Merina royalty originating with Andriamanelo, who is traditionally credited with founding Imerina in 1540.

Kingdom of Imerina Fanjakan'Imerina | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1540–1897 | |||||||

Standard of the Merina Kingdom

Coat of Arms (1896–97)

| |||||||

| Motto: "Tsy adidiko izaho samy irery, fa adidiko izaho sy ianao" (Malagasy) "It is not only my responsibility, but ours: mine and yours" | |||||||

| Anthem: Andriamanitra ô! Tahionao ny Mpanjakanay O God, bless our Queen | |||||||

Location of Madagascar in Africa | |||||||

| Capital | Antananarivo 18°55′25″S 47°31′56″E | ||||||

| Common languages | Malagasy | ||||||

| Religion | Traditional beliefs, Protestantism (from 1869)[1] | ||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (1540–1863) Constitutional monarchy (1863–1897) | ||||||

| Monarch | |||||||

• 1540–1575 | Andriamanelo (first) | ||||||

• 1883–1897 | Ranavalona III (last) | ||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||

• 1828–1833 | Andriamihaja (first) | ||||||

• 1896–1897 | Rasanjy (last) | ||||||

| Historical era | Pre-colonial | ||||||

• Accession of King Andriamanelo | 1540 | ||||||

• French capture of the royal palace | 1897 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | Madagascar | ||||||

| History of Madagascar |

|---|

|

|

|

In 1883, France invaded the Merina Kingdom to establish a protectorate. France invaded again in 1894 and conquered the kingdom, making it a French colony, in what became known as the Franco-Hova Wars.

History

Hova-Vazimba conflict

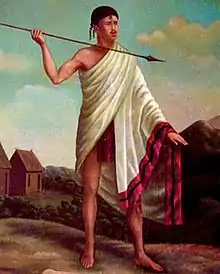

Madagascar's central highlands were first inhabited between 200 BC–300 AD by the island's earliest settlers,[2] the Vazimba, who appear to have arrived by pirogue from southeastern Borneo to establish simple villages in the island's dense forests.[3] By the 15th century the Hova people from the southeastern coast had gradually migrated into the central highlands[4] where they established hilltop villages interspersed among the existing Vazimba settlements, which were ruled by local kings and queens.[5] The two peoples coexisted peacefully for several generations and are known to have intermarried. In this way, a reigning Vazimba queen (alternately given in the oral histories as Rafohy or Rangita) married a Hova man named Manelobe. Their oldest son, Andriamanelo (r. 1540–1575), broke this tradition by launching a largely successful war to subjugate the surrounding Vazimba communities and force them to either submit to Hova dominance and assimilate, or flee.[6]

Andriamanelo was succeeded by his son Ralambo (r. 1575–1612), whose many enduring and significant political and cultural achievements earned him a heroic and near mythical status among the greatest ancient sovereigns of Merina history.[7] Ralambo was the first to assign the name of Imerina ("Land of the Merina people") to the central highland territories where he ruled.[8] Ralambo expanded and defended the Kingdom of Imerina through a combination of diplomacy and successful military action aided by the procurement of the first firearms in Imerina by way of trade with kingdoms on the coast. [9] Imposing a capitation tax for the first time (the vadin-aina, or "price of secure life"), he was able to establish the first standing Merina royal army[10] and established units of blacksmiths and silversmiths to equip them.[11] He famously repelled an attempted invasion by an army of the powerful western coastal Betsimisaraka people.[10] According to oral history, the wild zebu cattle that roamed the Highlands were first domesticated for food in Imerina under the reign of Ralambo,[12][13] and he introduced the practice and design of cattle pen construction,[12] as well as the traditional ceremony of the fandroana (the "Royal Bath"),[11] to celebrate his culinary discovery.[14]

Upon succeeding his father, Andrianjaka (1612–1630) led a successful military campaign to capture the final major Vazimba stronghold in the highlands on the hill of Analamanga. There he established the fortified compound (rova) that would form the heart of his new capital city of Antananarivo. Upon his orders, the first structures within this fortified compound (known as the Rova of Antananarivo) were constructed: several traditional royal houses were built, and plans for a series of royal tombs were designed. These buildings took on an enduring political and spiritual significance, ensuring their preservation until being destroyed by fire in 1995. Andrianjaka obtained a sizable cache of firearms and gunpowder, materials that helped to establish and preserve his dominance and expand his rule over greater Imerina.

Expansion of sovereignty

Political life on the island from the 16th century was characterised by sporadic conflict between the Merina and Sakalava kingdoms, originating with Sakalava slave-hunting incursions into Imerina.

By the early 19th century, the Merina were able to overcome rival tribes such as the Bezanozano, the Betsimisaraka, and eventually the Sakalava kingdom and bring them under the Merina crown. It is through this process that the ethnonym "Merina" began to be commonly used, as it denotes prominence in the Malagasy language.[15] Though some sources describe the Merina expansion as the unification of Madagascar, this period of Merina expansion was seen by neighboring tribes such as the Betsimisaraka as aggressive acts of colonialism.[16] By 1824, the Merina captured the port of Mahajanga situated on the western coast of the island marking a further expansion of power. Under Radama I, the Merina continued to launch military expeditions that both expanded imperial control and enriched military chiefs.[17] The ability of the Merina to overcome neighboring tribes was due to British firepower and military training. The British had an interest in establishing trade with the Merina kingdom due to its central position on the island since 1815. Merina imperial expeditions became more frequent and violent after the renunciation of the second Merina-British treaty. Between 1828 and 1840, more than 100,000 men were killed and more than 200,000 enslaved by Merina forces. Imperial rule was met with resistance from escaped slaves and other refugees from imperial rule numbering in the tens of thousands. These refugees formed raiding brigands that were dealt with by imperial troops who hunted them down in 1835. Notably, the rate of escaping refugees only heightened the demand for slave labor in the Merina kingdom, further fueling campaigns of military expansion.[18] Throughout the middle of the 19th century, continued imperial expansion and increasing control in coastal trade solidified Merina predominance over the island. The Merina kingdom nearly consolidated all of Madagascar into a single nation before French colonization in 1895.[19]

Division and civil war

King Andriamasinavalona quartered the kingdom to be ruled by his four favourite sons, producing persistent fragmentation and warfare between principalities in Imerina. He extended the borders of the kingdom to their largest historical extent prior to the kingdom's fragmentation.

Reunification

It was from this context in 1787 that Prince Ramboasalama, nephew of King Andrianjafy of Ambohimanga (one of the four kingdoms of Imerina) expelled his uncle and took the throne under the name Andrianampoinimerina. The new king used both diplomacy and force to reunite Imerina with the intent to bring all of Madagascar under his rule.

Kingdom of Madagascar

This objective was largely completed under his son, Radama I, who was the first to admit and regularly engage European missionaries and diplomats in Antananarivo.

The 33-year reign of Queen Ranavalona I, the widow of Radama I, was characterised by a struggle to preserve the cultural isolation of Madagascar from modernity, especially as represented by the French and British. Her son and heir, King Radama II, signed the unpopular Lambert Charter giving French entrepreneur Joseph-François Lambert exclusive rights to many of the island's resources. His liberal policies angered the aristocracy, however, and Prime Minister Rainivoninahitriniony had the King strangled in a coup d'état. This aristocratic revolution saw Rasoherina, the queen dowager, placed on the throne upon her acceptance of a constitutional monarchy that gave greater power to the Prime Minister. She replaced the incumbent Prime Minister with his brother, Rainilaiarivony, who retained the role for three decades and married each successive queen. The next sovereign, Ranavalona II, converted the nation to Christianity and had all the sampy (ancestral royal talismans) burnt in a public display. The last Merina sovereign, Queen Ranavalona III, acceded the throne at age 22 and was exiled to Réunion Island and later French Algeria following French colonisation of the island in 1896.

French colonisation

Angry at the cancellation of the Lambert Charter and seeking to restore property taken from French citizens, France invaded Madagascar in 1883 in what became known as the First Franco-Hova War (Hova referring to the andriana). At the war's end, Madagascar ceded Antsiranana (Diégo Suarez) on the northern coast to France and paid 560,000 gold francs to the heirs of Joseph-François Lambert. Meanwhile, in Europe, diplomats partitioning the African continent worked out an agreement whereby Britain, in order to obtain the Sultanate of Zanzibar, ceded its rights over Heligoland to the German Empire and renounced all claims to Madagascar in favor of France. The agreement proved detrimental for the monarchy of Madagascar. Prime Minister Rainilaiarivory had succeeded in playing Great Britain and France against one another, but now France could meddle without fear of reprisals from Britain.

In 1895, a French flying-column landed in Mahajanga (Majunga) and marched by way of the Betsiboka River to the capital, Antananarivo, taking the city's defenders by surprise since they had expected an attack from the much closer eastern coast. Twenty French soldiers died in combat while 6,000 died of malaria and other diseases before the Second Franco-Hova War ended. In 1896, the Merina Kingdom was put under French protection as the Malagasy Protectorate and in 1897 the French Parliament voted to annex the island as a colony, effectively ending Merina sovereignty.[20]

Geography

Spatial organization

Andriamanelo established the first fortified rova (royal compound) at his capital at Alasora. This fortified palace bore specific features – hadivory (dry moats), hadifetsy (defensive trenches) and vavahady (town gates protected by a large rolled stone disc acting as a barrier) – that rendered the town more resistant to Vazimba attacks.[21]

Andrianjaka's policies and tactics highlighted and increased the separation between the king and his subjects. He transformed social divisions into spatial divisions by assigning each clan to a specific geographical region within his kingdom.[22]

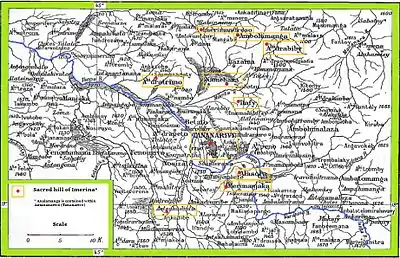

Andrianjaka unified the principalities on what he later designated as the twelve sacred hills of Imerina at Ambohitratrimo, Ambohimanga, Ilafy, Alasora, Antsahadita, Ambohimanambony, Analamanga, Ambohitrabiby, Namehana, Ambohidrapeto, Ambohijafy and Ambohimandranjaka. These hills became and remain the spiritual heart of Imerina, which was further expanded over a century later when Andrianampoinimerina redesignated the twelve sacred hills to include several different sites.[23]

Under Andriamasinavalona, the Kingdom of Imerina was composed of six provinces (toko): Avaradrano, constituting Antananarivo and land to the northeast of the capital, including Ambohimanga; Vakinisisaony, including the land to the south of Avaradrano and its capital at Alasora; Vonizongo to the northwest of Antananarivo with its capital at Fihaonana; Marovatana to the south of Vonizongo, with its capital at Ambohidratrimo; Ambodirano, south of Marovatana with its capital at Fenoarivo; and Vakinankaratra to the south of Antananarivo with its capital at Betafo. Andrianampoinimerina reunited these provinces and added Imamo to the west, which has been described by some historians as having been incorporated into Ambodirano, and by others as separate from it; and Valalafotsy to the northwest. Together, these areas constitute the core territory rightly called Imerina, the homeland of the Merina people.[24]

Imerina is located in the central highlands of Madagascar. It is notable that the word Imerina is derived from the Malagasy word meaning the "occupancy of a prominent place." Consistent with the name, much of the documented manipulation of the land in the Merina kingdom involve the building of palaces for royalty or of temples. Andrianampoinimerina (c.1745-1809) was the first to use the toponym of Imerina after conquering Antananarivo. He projected his power by constructing a palace on the site that became the seat of royal power in the Merina kingdom.[25]

A significant alteration of the landscape made under the rule of Andrianampoinimerina was the introduction of irrigation systems that allowed for the farming of rice paddies. To the present day rice remains a staple of Malagasy cuisine. The digging of canals and dikes was done by vast numbers of slaves placed under royal servitude, or fanompoana.[25]

The landscape of Imerina and its geographical manipulation had significant ritual meaning in Merina culture. The irrigation system introduced to Antananarivo, the central authority of Imerina, represented the unification between the Merina royalty and its people. This infrastructural feat paralleled the ritual sprinkling of water known as tsodrano done to represent the unification of land and people. Merina beliefs held the connection between cultural history and the landscape in high regard. The use of water to represent spiritual connections between people, the land, and ancestors remains common in the present day.[25]

By the 1820s, an increased European population had superimposed many Western geographic features onto Imerina. This involved the introduction of non native plants and trees. This proved particularly successful for Europeans as the Malagasy soil and climate were particularly conducive to growing European plants and vegetables.[25]

Social organization

Caste system

Before the unification of the Merina kingdom under Andrianampoinimerina, the social structure of the central highlands of Madagascar were distinguished by a class of petty princes and peasant masses.[26]

Andriamanelo was reportedly the first to formally establish the andriana as a caste of Merina nobles, thereby laying the foundation for a stratified and structured society.[27] From this point forward, the term Hova was used to refer only to the non-noble free people of the society which would later be renamed Merina by Andriamanelo's son Ralambo.[8] The first sub-divisions of the andriana noble caste were created when Ralambo split it into four ranks.[13]

Andrianjaka was the first king to be buried on the grounds of the Rova of Antananarivo, his tomb forming the first of the Fitomiandalana (seven tombs placed in a row on the Rova grounds).[28] To commemorate his greatness, his subjects erected a small wooden house called a small sacred house on top of his tomb. Future Merina sovereigns and nobles continued to construct similar tomb houses on their tombs well into the 19th century.[29]

After the conquests of the 19th century, approximately half of the Merina population consisted of the descendants of slaves. This distinction is calcified in the present day by the classification of the descendants of slaves as "blacks" and those of freemen as "whites". The use of color to describe social distinction is further supplemented by the racial distinctions of the Malagasy population tracing back to the original settlement of the island, with Austronesian racial features are contrasted by African racial features.[26][30]

Religion

Andriamanelo is credited with introducing astrology (sikidy) in Imerina.[31] The Merina rite of circumcision, described by Bloch (1986) in great detail, continued to be practiced by the Merina monarchy through the end of the 19th century in precisely the way first established by Andriamanelo generations before. Many elements of these rituals continue to form part of the circumcision traditions of Merina families in the 21st century. The origins of these practices can be traced back to the southeastern part of the island that the Hova had left behind as they migrated into the central highlands. Astrology, for instance, had been introduced early to the island by way of trade contacts between coastal Malagasy communities and Arab seafarers.[32]

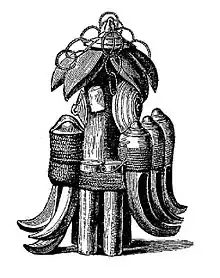

Under Andriamanelo's son Ralambo, the sovereign became imbued with increasing power to protect the realm. This was preserved by honoring the sampy, traditional amulets made from assorted natural materials. Amulets and idols called ody had long occupied an important place among many ethnic groups of Madagascar, but these were believed to offer protection to the individual wearer only and were commonplace objects possessed by anyone from slave children to kings. After Ralambo received a highly powerful sampy called Kelimalaza that was distinguished by its supposed capacity to extend protection to an entire community, he sought out and amassed a total of twelve others from communities across Imerina believed to have such a quality. These sampy were personified—complete with a distinct personality—and offered their own house with guardians dedicated to their service. Ralambo then transformed the nature of the relationship between sampy and ruler: whereas previously the sampy had been seen as tools at the disposal of community leaders, under Ralambo they became divine protectors of the king's sovereignty and the integrity of the state, which would be preserved through their power on the condition that the line of sovereigns ensured the sampy were shown the respect due to them. By collecting the twelve greatest sampy—twelve being a sacred number in Merina cosmology—and transforming their nature, Ralambo strengthened the supernatural power and legitimacy of the royal line of Imerina.[33] Oral history recounts numerous instances where sampy were taken into battle, and subsequent successes and varying miracles were attributed to them, including several key victories against Sakalava marauders.[9] The propagation of similar sampy at the service of less powerful citizens consequently increased throughout Imerina under Ralambo's rule: nearly every village chief, as well as many common families, had one in their possession and claimed the powers and protection their communal sampy offered them.[13] These lesser sampy were destroyed or reduced to the status of ody by the end of the reign of Ralambo's son, Andrianjaka, officially leaving only twelve truly powerful sampy (known as the sampin'andriana: the "Royal Sampy") which were all in the possession of the king.[13] These royal sampy, including Kelimalaza, continued to be worshiped until their supposed destruction in a bonfire by Queen Ranavalona II upon her public conversion to Christianity in 1869.[34]

Also beginning under Ralambo, the ritual sanctification of the realm occurred through the annual fandroana festival at the start of each year. Although the precise form of the original holiday cannot be known with certainty and its traditions have evolved over time, 18th- and 19th-century accounts provide insight into the festival as it was practiced at that time.[35] Accounts from these centuries indicate that all family members were required to reunite in their home villages during the festival period. Estranged family members were expected to attempt to reconcile. Homes were cleaned and repaired and new housewares and clothing were purchased. The symbolism of renewal was particularly embodied in the traditional sexual permissiveness encouraged on the eve of the fandroana (characterized by early 19th-century British missionaries as an "orgy") and the following morning's return to rigid social order with the sovereign firmly at the helm of the kingdom.[35] On this morning, the first day of the year, a red rooster was traditionally sacrificed and its blood used to anoint the sovereign and others present at the ceremony. Afterward the sovereign would bathe in sanctified water, then sprinkle it upon attendees to purify and bless them and ensure an auspicious start to the year.[14] Children would celebrate the fandroana by carrying lighted torches and lanterns in a nighttime processional through their villages. The zebu meat eaten over the course of the festival was primarily grilled or consumed as jaka, a preparation reserved uniquely for this holiday. This delicacy was made during the festival by sealing shredded zebu meat with suet in a decorative clay jar. The confit would then be conserved in a pit for twelve months to be served at the next year's fandroana.[36]

Customs

The marriage tradition of the vodiondry, still practiced to this day throughout the Highlands, is said to have originated with Andriamanelo. According to oral history, after the sovereign had successfully contracted a marriage with Ramaitsoanala, sole daughter of Vazimba King Rabiby, Andriamanelo sent her a variety of gifts including vodiondry—meat from the hindquarters of a sheep—which he believed to be the tastiest portion.[37] The value placed on this cut of meat was reaffirmed by Ralambo who, upon discovering the edibility of zebu meat, declared the hindquarters of every slaughtered zebu throughout the kingdom to be his royal due. From the time of Andriamanelo forward, it became a marriage tradition for the groom to offer vodiondry to the bride's family. Over time the customary offerings of meat have been increasingly replaced by a symbolic piastre, sums of money and other gifts.[38] Andriamanelo's son Ralambo is credited with introducing the tradition of polygamy in Imerina.[11] He also introduced the traditions of circumcision and family intermarriage (such as between parent and step-child, or between half-siblings) among Merina nobles, these practices having already existed among certain other Malagasy ethnic groups.[11]

According to oral history, the institution of lengthy formal mourning periods for deceased sovereigns in Imerina may also have begun with the death of Andrianjaka. He was succeeded by his son, Andriantsitakatrandriana.[28]

Despite plenty of religious variation across Imerina and the Malagasy highlands in general, ritual circumcision has remained a constant factor in Merina and Malagasy culture. The permanence of the circumcision ritual continues to the modern day.[39]

Indigenous silk clothing (landibe) is especially important in highland cultures, including with the Merina. It was worn during ancestral funerary ceremonies.[40]

The Tantaran'ny Andriana or Histories of Kings is the written classic of Merina culture, compiled from oral traditions and stories. The Tantara was collected by the Jesuit priest François Callet in the 1860s. The Tantara and other printed works are held in such high regard that very few can be obtained for any price.[41]

Present day Malagasy culture is still tied extensively to the past. Many ceremonies involve reenactments of the past, such as tromba, or the spirit possession ceremony. Generally, the concept of history in Madagascar places a great emphasis on feeling and experiencing rather than knowing.[42]

Political organization

The line of succession in Imerina used a system called fanjakana arindra ("organized government"),[43] which was established by the Vazimba noblewomen who raised Andriamanelo, founder of Imerina. While the Vazimba had historically tended to favor rule by queens, the Hova favored male heirs, and the marriage between Andriamanelo's Vazimba and Hova parents had produced two sons and a daughter. To prevent conflict, the queen decided that Andriamanelo would inherit the crown upon his mother's death and would be succeeded not by his own child but by his younger brother.[44] This system of succession was ordered by the queens to be followed for all time, and applied to families as well: in any instance where there was an elder child and a younger one, the parents would designate an elder child to assume authority within the family upon their death, and that authority would be handed to the designated younger child in the event of the death of the elder child.[43] Ralambo was the first Merina sovereign to practice polygamy, and his second wife was the first to give him a son. While his younger son by his first wife was to rule, Ralambo sought to assuage the elder son by declaring that the crown could henceforth only be passed to a child born of the reigning sovereign and a princess from the elder son Andriantompokoindrindra's family line.[45]

The practice of sanctifying deceased Merina sovereigns is believed to have originated with Ralambo.[11]

Imerina was initially ruled under Andriamanelo from his mother's home village of Alasora. The capital was shifted by his son Ralambo to Ambohidrabiby, location of the former capital of his maternal grandfather King Rabiby. Andrianjaka moved his capital from Ambohidrabiby to Ambohimanga upon ascending to the throne around 1610.[45] The Besakana, Masoandrotsiroa and Fitomiandalana houses at the Rova of Antananarivo were preserved and maintained over the centuries by successive generations of Merina sovereigns, imbuing the structures with deep symbolic and spiritual meaning. As Andrianjaka's residence, the Besakana was particularly significant: the original building was torn down and reconstructed in the same design by Andriamasinavalona around 1680, and again by Andrianampoinimerina in 1800, each of whom inhabited the building in turn as their personal residence. King Radama I likewise inhabited the building for much of his time at the Rova,[46] and in 1820 he designated the building as the first site to house what came to be known as the Palace School, the first formal European-style school in Imerina.[47] Sovereigns were enthroned in this building and their mortal remains were displayed here before burial,[48] rendering Besakana "the official state room for civil affairs... regarded as the throne of the kingdom."[49]

Defense

The early Merina fighters under the first king of Imerina were equipped with iron-tipped spears, an innovation credited to Andriamanelo himself, who may have been the first among the Hova to use smithed iron in this way.[50]

Justice system

Andrianjaka imposed an intimidating change to the traditional form of justice, the trial by ordeal: rather than administering tangena poison to an accused person's rooster to determine their innocence by the creature's survival, the poison would instead be ingested by the accused himself.[51]

Economy and trade

Andriamanelo was the first in the highlands to transform lowland swamps into irrigated rice paddies through the construction of dikes in the valleys around Alasora.[52] Under Andrianjaka, the plains surrounding Antananarivo were gradually transformed into vast, surplus-producing rice paddies.[53] This feat was accomplished by mobilizing large numbers of his able-bodied subjects to construct dikes that enabled the redirection of rainwater for controlled flooding of planted areas.[54]

Andrianjaka was reportedly the first Merina leader to receive Europeans around 1620 and traded slaves in exchange for guns and other firearms to aid in the pacification of rival principalities, obtaining 50 guns and three barrels of gunpowder to equip his army.[29]

Technology

Andriamanelo is traditionally credited with discovering the technique of silversmithing, iron smithing and the construction and use of pirogues.[31] While these technologies were not discovered during his reign, Andriamanelo may have been among the first sovereigns in Imerina to make wide-scale use of them.[50]

The Slave Trade

_(14764052875).jpg.webp)

Export of slaves

Captives from tribal raids were made into the Malagasy slave population. Surpluses of these populations were sent to foreign traders on the coast. These traders were initially Arab and Indian, though Europeans began to join those demanding slaves at the start of the 16th century. Malagasy slaves were exported to Arabia, India, Réunion and Mauritius, and the Americas, primarily Brazil.[55]

British influence

After the British emerged victorious from the Napoleonic wars, they captured the French Mascarene Islands which lie east of Madagascar. These islands facilitated the export of slaves and agricultural products. Some of the first stories of Madagascar to be told in Britain were those told by Robert Drury, a shipwrecked British sailor who wrote about the Malagasy slave trade of in his journal that would be published and widely distributed in England.[56] It was this fixation on the slave trade in Madagascar that initially drew the British to the Merina, giving the Merina the firepower to extend their empire and trading networks across Madagascar. Though the British later returned the island of Réunion to France, they retained Mauritius and included it in the second British-Merina treaty of 1820. This treaty declared an end to the export of slaves in Madagascar under the Merina crown. However, the internal slave market still boomed after 1820 despite British efforts. It is estimated that between 6,000 to 10,000 slaves per year were exported from Antananarivo by 1820.[57] In 1828, Ranavalona I revoked the second British-Merina treaty and expelled most foreigners from Madagascar by 1836.[58]

Domestic slavery

Due to the thin population density of Madagascar, domestic slavery was a way to broadcast control over resources and manpower. The elite of Imerina relied heavily upon slave labor. Because of this, the Merina king Radama I had little intent to abide by the first British-Merina treaty signed in 1817. Slave ownership became increasingly common in the following decades. As the slave caste expanded, more and more of the Merina population began holding slaves. As imperial conquests continually increased the supply of slaves captured from neighboring tribes, the population of Antananarivo grew from around 10,000 in 1820 to 50,000 in 1833. The demand in slaves matched the rise in supply as a result of fanompoana, or mandatory military service, being established in the Merina kingdom thereby drawing able bodied free men away from agricultural labor and into the army.[59] In the second half of the 19th century, the Merina had begun to import slaves from East Africa. This was driven by an economy that critically relied on slave labor as well as the demands of Merina court officials that had personal financial interests. Emancipation of domestic slaves began in 1877, when an estimated 150,000 slaves were freed. However, these newly freed slaves were made into an imperial labor reserve, a position not far removed from enslavement. A clandestine trade thrived in the 1880s until Franco-Merina hostilities broke out in 1882.

See also

- List of Imerina monarchs

References

- Nielssen, Hilde (2011). Ritual Imagination: A Study of Tromba Possession Among the Betsimisaraka in Eastern Madagascar. BRILL. p. 50. ISBN 9789004215245.

where the Protestant church became the state religion of the Merina Kingdom in1869

- Crowley, B.E. (2010). "A refined chronology of prehistoric Madagascar and the demise of the megafauna". Quaternary Science Reviews. 29 (19–20): 2591–2603. Bibcode:2010QSRv...29.2591C. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.06.030.

- Dahl 1991, p. 72.

- Campbell, Gwyn (1993). "The Structure of Trade in Madagascar, 1750–1810". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 26 (1): 111–148. doi:10.2307/219188. JSTOR 219188.

- Ranaivoson 2005, p. 35.

- Raison-Jourde 1983, p. 142.

- Bloch 1971, p. 17.

- Kus 1995, pp. 140–154.

- de la Vaissière & Abinal 1885, pp. 63–71.

- Kent 1968, pp. 517–546.

- Ogot 1992, p. 876.

- Bloch 1985, pp. 631–646.

- Raison-Jourde 1983, pp. 141–142.

- de la Vaissière & Abinal 1885, pp. 285–290.

- Larson, Pier M. (1996). "Desperately Seeking 'the Merina' (Central Madagascar): Reading Ethnonyms and Their Semantic Fields in African Identity Histories". Journal of Southern African Studies. 22 (4): 541–560. doi:10.1080/03057079608708511. ISSN 0305-7070. JSTOR 2637156.

- Cole, Jennifer, 1966- (2001). Forget colonialism? : sacrifice and the art of memory in Madagascar. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92682-0. OCLC 49570321.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Campbell, Gwyn (1981). "Madagascar and the Slave Trade, 1810-1895". The Journal of African History. 22 (2): 203–227. doi:10.1017/S0021853700019411. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 181583. S2CID 161991146.

- Campbell, Gwyn (1981). "Madagascar and the Slave Trade, 1810-1895". The Journal of African History. 22 (2): 203–227. doi:10.1017/S0021853700019411. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 181583. S2CID 161991146.

- "Merina | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2019-12-21. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- Thompson & Adloff 1965, p. 142.

- de la Vaissière & Abinal 1885, p. 62.

- Campbell 2005, p. 120.

- Administration Colonielle 1898, p. 895.

- Campbell 2012, p. 500.

- Bird, Randall (December 2005). "The Merina Landscape in Early Nineteenth Century Highlands Madagascar". African Arts. 38 (4): 18–92. doi:10.1162/afar.2005.38.4.18. ISSN 0001-9933.

- Bloch, Maurice (February 1971). "The Implications of Marriage Rules and Descent: Categories for Merina Social Structures". American Anthropologist. 73 (1): 164–178. doi:10.1525/aa.1971.73.1.02a00120. ISSN 0002-7294.

- Miller & Rowlands 1989, p. 143.

- Piolet (1895), pp. 209–210

- Chapus & Dandouau 1961, p. 47.

- Randrianja, Solofo. (2009). Madagascar : a short history. Ellis, Stephen, 1953-2015. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-70420-3. OCLC 243845225.

- Piolet 1895, p. 206.

- Radimilahy 1993, pp. 478–483.

- Graeber 2007, pp. 35–38.

- Oliver 1886, p. 118.

- Larson 1999, p. 37–70.

- Raison-Jourde 1983, p. 29.

- Kent, R.K. (1968). "Madagascar and Africa II: The Sakalava, Maroserana, Dady and Tromba before 1700". The Journal of African History. 9 (4): 517–546. doi:10.1017/S0021853700009026. S2CID 162880175.

- Grandidier, Guillaume (1913). "Le mariage à Madagascar". Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris. 4: 9–46. doi:10.3406/bmsap.1913.8571. Archived from the original on May 15, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- Berger, Laurent (December 2012). "Ritual, history and cognition: From analogy to hegemony in highland Malagasy polities". Anthropological Theory. 12 (4): 351–385. doi:10.1177/1463499612470908. ISSN 1463-4996. S2CID 147010771.

- Green, Rebecca L. (June 2009). "Conceptions of Identity and Tradition in Highland Malagasy Clothing". Fashion Theory. 13 (2): 177–214. doi:10.2752/175174109X415069. ISSN 1362-704X. S2CID 191585630.

- Kent, Raymond K. (1970). Early kingdoms in Madagascar, 1500-1700. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-084171-2. OCLC 97334.

- Emoff, Ron (Spring–Summer 2002). "Phantom Nostalgia and Recollecting (From) the Colonial Past in Tamatave, Madagascar". Ethnomusicology. 46 (2): 265–283. doi:10.2307/852782. JSTOR 852782.

- Raison-Jourde 1983, p. 239.

- Kus 1982, pp. 47–62.

- City of Antananarivo. "Antananarivo: Histoire de la commune" (in French). Archived from the original on 23 February 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- Frémigacci 1999, p. 427.

- Ralibera 1993, p. 196.

- Oliver 1886, pp. 241–242.

- Featherman 1888.

- Madatana (2011). "Alasora: Royaume d'Andriamanelo et terre des Velondraiamandreny" (in French). www.madatana.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2010.

- Kent (1970), p.

- Rafidinarivo 2009, p. 84.

- Raison-Jourde (1983), p. 238

- Chapus & Dandouau 1961, pp. 47–48.

- Campbell, Gwyn (1981). "Madagascar and the Slave Trade, 1810-1895". The Journal of African History. 22 (2): 203–227. doi:10.1017/S0021853700019411. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 181583. S2CID 161991146.

- Drury, Robert. (1750). The pleasant and surprizing adventures of Mr. Robert Drury, during his fifteen years captivity on the island of Madagascar : Containing I. His voyage to, and short stay at the East Indies. II. An Account of the shipwreck of the degrave, on the island of Madagasear; the murder of capt. Younge and his ship's company, except admiral Bembo's son, and some few others, who made their escape. III. His captivity, hard usage, marriage, and wonderful variety of fortune. IV. His travels thorow the island, and description of its situation, product, manufactures, commodities, &c. V. The nature of the people, their customs, wars, religion, and policy: as also, the conferences between some of their chiefs, and the author, concerning the Christian, and their religion. VI. His redemption from thence by Capt. Mackett, late commander of the Prince of Wales, in the Honourable East India Company's Service: His arrival in England, and second voyage thither. VII. A vocabulary of the Madagasear language. The whole is a faithful narrative of matter of fact, interspers'd with a variety of amazing incidents, and illustrated with a sheet map of Madagasear and other cuts. First written by himself, and now carefully revised and corrected from the original copy, with improvements. Printed for and sold by M. Sheepey, under the Royal Exchange. OCLC 695946230.

- Campbell, Gwyn (1981). "Madagascar and the Slave Trade, 1810-1895". The Journal of African History. 22 (2): 203–227. doi:10.1017/S0021853700019411. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 181583. S2CID 161991146.

- Campbell, Gwyn (1981). "Madagascar and the Slave Trade, 1810-1895". The Journal of African History. 22 (2): 203–227. doi:10.1017/S0021853700019411. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 181583. S2CID 161991146.

- Campbell, Gwyn (1981). "Madagascar and the Slave Trade, 1810-1895". The Journal of African History. 22 (2): 203–227. doi:10.1017/S0021853700019411. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 181583. S2CID 161991146.

Bibliography

- Administration Colonielle (1898). "L'habitation à Madagascar". Colonie de Madagascar: Notes, reconnaissances et explorations (in French). Vol. 4. Imprimerie Officielle de Tananarive.

- Berger, Laurent (2012). “Ritual, History and Cognition: From Analogy to Hegemony in Highland Malagasy Polities.” Anthropological Theory, vol. 12, no. 4, Dec. 2012, pp. 351–385, doi:10.1177/1463499612470908.

- Bird, Randall (2005). “The Merina Landscape in Early Nineteenth Century Highlands Madagascar.” African Arts, vol. 38, no. 4, 2005, pp. 18–92. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20447730.

- Bloch, Maurice (1971). Placing the dead: tombs, ancestral villages and kinship organization in Madagascar. Berkeley Square, UK: Berkeley Square House. ISBN 978-0-12-809150-0.

- Bloch, Maurice (1985). "Almost Eating the Ancestors". Man. 20 (4): 631–646. doi:10.2307/2802754. JSTOR 2802754.

- Campbell, G. (1981). Madagascar and the Slave Trade, 1810-1895. The Journal of African History, 22(2), 203-227. Retrieved March 26, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/181583

- Campbell, Gwyn (2005). An economic history of Imperial Madagascar, 1750–1895: the rise and fall of an island empire. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83935-8.

- Campbell, Gwyn (2012). David Griffiths and the Missionary "History of Madagascar". Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-19518-9.

- Chapus, Georges-Sully; Dandouau, Andre (1961). Manuel d'histoire de Madagascar (in French). Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose.

- Cole, Jennifer (2001). Forget Colonialism? Sacrifice and the Art of Memory in Madagascar. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520228467

- Dahl, Otto (1991). Migration from Kalimantan to Madagascar. Oslo: Norwegian University Press. ISBN 978-82-00-21140-2.

- Drury, Robert, and Daniel Defoe. The Pleasant and Surprizing Adventures of Mr. Robert Drury, during His Fifteen Years Captivity on the Island of Madagascar: Containing I. His Voyage to, and Short Stay at the East Indies. II. An Account of the Shipwreck of the Degrave, on the Island of Madagasear; the Murder of Capt. Younge and His Ship's Company, except Admiral Bembo's Son, and Some Few Others, Who Made Their Escape. III. His Captivity, Hard Usage, Marriage, and Wonderful Variety of Fortune. IV. His Travels Thorow the Island, and Description of Its Situation, Product, Manufactures, Commodities, &c. V. The Nature of the People, Their Customs, Wars, Religion, and Policy: as Also, the Conferences between Some of Their Chiefs, and the Author, Concerning the Christian, and Their Religion. VI. His Redemption from Thence by Capt. Mackett, Late Commander of the Prince of Wales, in the Honourable East India Company's Service: His Arrival in England, and Second Voyage Thither. VII. A Vocabulary of the Madagasear Language. The Whole Is a Faithful Narrative of Matter of Fact, Interspers'd with a Variety of Amazing Incidents, and Illustrated with a Sheet Map of Madagasear and Other Cuts. First Written by Himself, and Now Carefully Revised and Corrected from the Original Copy, with Improvements. Printed for and Sold by M. Sheepey, under the Royal Exchange; J. Wren, near Great Turn Style. Holborn; and T. Lownds, Exeter Exchange in the Strand, 1750.

- Emoff, R. (2002). Phantom Nostalgia and Recollecting (From) the Colonial Past in Tamatave, Madagascar. Ethnomusicology, 46(2), 265-283. doi:10.2307/852782

- Featherman, Americus (1888). Social history of the races of mankind Volume 2, Part 2. London: Trübner & co.

- Frémigacci, Jean (1999). "Le Rova de Tananarive: Destruction d'un lieu saint ou constitution d'une référence identitaire?". In Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (ed.). Histoire d'Afrique (in French). Antananarivo: Karthala Editions. pp. 421–444. ISBN 9782865379040.

- Graeber, David (2007). Lost People: Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21915-2.

- Green, Rebecca L (2009). "Conceptions of Identity and Tradition in Highland Malagasy Clothing." Fashion Theory, vol. 13, no. 2, Routledge, June 2009, pp. 177–214, doi:10.2752/175174109X415069.

- Kent, Raymond Knezevich (1970). Early Kingdoms in Madagascar, 1500-1700. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 9780030841712

- Kus, Susan (1982). "Matters Material and Ideal". In Hodder, Ian (ed.). Symbolic and Structural Archaeology. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24406-0.

- Kus, Susan (1995). "Sensuous human activity and the state: towards an archaeology of bread and circuses". In Miller, Daniel; Rowlands, Michael (eds.). Domination and Resistance. London: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-12254-2.

- Larson, Pier M (1996). “Desperately Seeking 'the Merina' (Central Madagascar): Reading Ethnonyms and Their Semantic Fields in African Identity Histories.” Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 22, no. 4, 1996, pp. 541–560. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2637156.

- Larson, Pier M. (1999), "A cultural politics of bedchamber construction and progressive dining in Antananarivo: ritual inversions during the fandroana of 1817", in Middleton, Karen (ed.), Ancestors, Power and History in Madagascar, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp. 37–70, ISBN 978-90-04-11289-6

- Miller, Daniel; Rowlands, Michael (1989). Domination and Resistance. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-12254-2.

- Ogot, Bethwell A. (1992). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century (in French). Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-0-520-06700-4.

- Oliver, Samuel (1886). Madagascar: An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Island and its Former Dependencies, Volume 1. New York: Macmillan and Co.

- Piolet, Jean-Baptiste (1895). Madagascar et les Hova: déscription, organisation, histoire (in French). Paris: C. Delagrave.

- Radimilahy, Chantal (1993). "Ancient Iron-working in Madagascar". In Shaw, Thurstan (ed.). The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-11585-8.

- Rafidinarivo, Christiane (2009). Empreintes de la servitude dans les sociétés de l'océan Indien: métamorphoses et permanences (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-8111-0276-0.

- Raison-Jourde, Françoise (1983). Les souverains de Madagascar (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-86537-059-7.

- Ralibera, Daniel (1993), Madagascar et le christianisme (in French), Editions Karthala, ISBN 9789290282112, retrieved January 7, 2011

- Ranaivoson, Dominique (2005). Madagascar: dictionnaire des personnalités historiques (in French). Paris: Sépia. ISBN 978-2-84280-101-4.

- Randrianja, Solofo, and Stephen Ellis (2009). Madagascar: a Short History. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226704203

- Thompson, Virginia; Adloff, Richard (1965). The Malagasy Republic: Madagascar today. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Sanchez, Samuel F. (2019). “The value of the “royal bath” (fandroana). Tributary exchanges and sovereignty in the kingdom of Madagascar (19th century)” Revue d'Histoire du XIXe siècle, no. 59, Dec. 2019 Sanchez, Samuel F., The value of the “royal bath” (fandroana). Tributary exchanges and sovereignty in the kingdom of Madagascar (19th century)

- de la Vaissière, Camille; Abinal, Antoine (1885). Vingt ans à Madagascar: colonisation, traditions historiques, moeurs et croyances (in French). Paris: V. Lecoffre.