Kushan Empire

The Kushan Empire (Ancient Greek: Βασιλεία Κοσσανῶν; Bactrian: Κυϸανο, Kushano; Sanskrit: कुषाण वंश; Brahmi: ![]()

![]()

![]() , Ku-ṣā-ṇa; BHS: Guṣāṇa-vaṃśa; Parthian: 𐭊𐭅𐭔𐭍 𐭇𐭔𐭕𐭓, Kušan-xšaθr; Chinese: 貴霜 Guì-shuāng[19]) was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, in the Bactrian territories in the early 1st century. It spread to encompass much of modern-day territory of, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, and northern India,[20][21][22] at least as far as Saketa and Sarnath near Varanasi (Benares), where inscriptions have been found dating to the era of the Kushan Emperor Kanishka the Great.[note 3]

, Ku-ṣā-ṇa; BHS: Guṣāṇa-vaṃśa; Parthian: 𐭊𐭅𐭔𐭍 𐭇𐭔𐭕𐭓, Kušan-xšaθr; Chinese: 貴霜 Guì-shuāng[19]) was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, in the Bactrian territories in the early 1st century. It spread to encompass much of modern-day territory of, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, and northern India,[20][21][22] at least as far as Saketa and Sarnath near Varanasi (Benares), where inscriptions have been found dating to the era of the Kushan Emperor Kanishka the Great.[note 3]

Kushan Empire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30–375 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg.webp) A map of India in the 2nd century AD showing the extent of the Kushan Empire (in yellow) during the reign of Kanishka. Most historians consider the empire to have variously extended as far east as the middle Ganges plain,[6] to Varanasi on the confluence of the Ganges and the Jumna,[7][8] or probably even Pataliputra.[9][5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Bagram (Ancient Kapisa) Peshawar (Puruṣapura) Taxila (Takṣaśilā) Mathura (Mathurā) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Greek (official until ca. 127)[note 1] Bactrian[note 1] (official from ca. 127)[note 2] Gandhari Prakrit[12] Hybrid Sanskrit[12] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism[13] Hinduism[14] Zoroastrianism[15] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Kushanas (Yuezhi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 30–80 | Kujula Kadphises | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 350–375 | Kipunada | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical Antiquity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Kujula Kadphises unites Yuezhi tribes into a confederation | 30 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 375 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Est. 70[17] | 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Est. 200[18] | 2,500,000 km2 (970,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Kushan drachma | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Kushans were most probably one of five branches of the Yuezhi confederation,[26][27] an Indo-European nomadic people of possible Tocharian origin,[28][29][30][31][32] who migrated from northwestern China (Xinjiang and Gansu) and settled in ancient Bactria.[27] The founder of the dynasty, Kujula Kadphises, followed Greek religious ideas and iconography after the Greco-Bactrian tradition, and also followed traditions of Hinduism, being a follower of Shaivism.[33][34] The Kushans in general were also great patrons of Buddhism, and, starting with Emperor Kanishka, they also employed elements of Zoroastrianism in their pantheon.[35] They played an important role in the spread of Buddhism to Central Asia and China.

The Kushans possibly used the Greek language initially for administrative purposes, but soon began to use the Bactrian language. Kanishka sent his armies north of the Karakoram mountains. A direct road from Gandhara to China remained under Kushan control for more than a century, encouraging travel across the Karakoram and facilitating the spread of Mahayana Buddhism to China. The Kushan dynasty had diplomatic contacts with the Roman Empire, Sasanian Persia, the Aksumite Empire and the Han dynasty of China. The Kushan Empire was at the center of trade relations between the Roman Empire and China: according to Alain Daniélou, "for a time, the Kushana Empire was the centerpoint of the major civilizations".[36] While much philosophy, art, and science was created within its borders, the only textual record of the empire's history today comes from inscriptions and accounts in other languages, particularly Chinese.[37]

The Kushan Empire fragmented into semi-independent kingdoms in the 3rd century AD, which fell to the Sasanians invading from the west, establishing the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom in the areas of Sogdiana, Bactria and Gandhara. In the 4th century, the Guptas, an Indian dynasty also pressed from the east. The last of the Kushan and Kushano-Sasanian kingdoms were eventually overwhelmed by invaders from the north, known as the Kidarites, and then the Hephthalites.[16]

Origins

Chinese sources describe the Guìshuāng (貴霜, Old Chinese: *kuj-s [s]raŋ), i.e. the Kushans, as one of the five aristocratic tribes of the Yuezhi.[40] Many scholars believe that the Yuezhi were a people of Indo-European origin.[28][41] A specifically Tocharian origin of the Yuezhi is often suggested.[28][29][30][31][32][42] An Iranian, specifically Saka,[43] origin, also has some support among scholars.[44] Others suggest that the Yuezhi might have originally been a nomadic Iranian people, who were then partially assimilated by settled Tocharians, thus containing both Iranian and Tocharian elements.[45]

The Yuezhi were described in the Records of the Great Historian and the Book of Han as living in the grasslands of eastern Xinjiang and northwestern part of Gansu, in the northwest of modern-day China, until their King was beheaded by the Xiongnu (匈奴) who were also at war with China, which eventually forced them to migrate west in 176–160 BC.[46] The five tribes constituting the Yuezhi are known in Chinese history as Xiūmì (休密), Guìshuāng (貴霜), Shuāngmǐ (雙靡), Xìdùn (肸頓), and Dūmì (都密).

The Yuezhi reached the Hellenic kingdom of Greco-Bactria (in northern Afghanistan and Uzbekistan) around 135 BC. The displaced Greek dynasties resettled to the southeast in areas of the Hindu Kush and the Indus basin (in present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan), occupying the western part of the Indo-Greek Kingdom.

In India, Kushan emperors regularly used the dynastic name ΚΟϷΑΝΟ ("Koshano") on their coinage.[19] Several inscriptions in Sanskrit in the Brahmi script, such as the Mathura inscription of the statue of Vima Kadphises, refer to the Kushan Emperor as ![]()

![]()

![]() , Ku-ṣā-ṇa ("Kushana").[19][47] Some later Indian literary sources referred to the Kushans as Turushka, a name which in later Sanskrit sources[note 4] was confused with Turk, "probably due to the fact that Tukharistan passed into the hands of the western Turks in the seventh century".[48][49] According to John M. Rosenfield, Turushka, Tukhāra or Tukhāra are variations of the word Tokhari in Indian writings.[50] Yet, according to Wink, "nowadays no historian considers them to be Turkish-Mongoloid or 'Hun', although there is no doubt about their Central-Asian origin."[48]

, Ku-ṣā-ṇa ("Kushana").[19][47] Some later Indian literary sources referred to the Kushans as Turushka, a name which in later Sanskrit sources[note 4] was confused with Turk, "probably due to the fact that Tukharistan passed into the hands of the western Turks in the seventh century".[48][49] According to John M. Rosenfield, Turushka, Tukhāra or Tukhāra are variations of the word Tokhari in Indian writings.[50] Yet, according to Wink, "nowadays no historian considers them to be Turkish-Mongoloid or 'Hun', although there is no doubt about their Central-Asian origin."[48]

Early Kushans

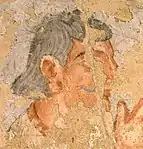

Some traces remain of the presence of the Kushans in the area of Bactria and Sogdiana in the 2nd-1st century BC, where they had displaced the Sakas, who moved further south.[52] Archaeological structures are known in Takht-i Sangin, Surkh Kotal (a monumental temple), and in the palace of Khalchayan. On the ruins of ancient Hellenistic cities such as Ai-Khanoum, the Kushans are known to have built fortresses. Various sculptures and friezes from this period are known, representing horse-riding archers,[53] and, significantly, men such as the Kushan prince of Khalchayan with artificially deformed skulls, a practice well attested in nomadic Central Asia.[54][55] Some of the Khalchayan sculptural scenes are also thought to depict the Kushans fighting against the Sakas.[56] In these portrayals, the Yuezhis are shown with a majestic demeanour, whereas the Sakas are typically represented with side-whiskers, and more or less grotesque facial expressions.[56]

The Chinese first referred to these people as the Yuezhi and said they established the Kushan Empire, although the relationship between the Yuezhi and the Kushans is still unclear. Ban Gu's Book of Han tells us the Kushans (Kuei-shuang) divided up Bactria in 128 BC. Fan Ye's Book of Later Han "relates how the chief of the Kushans, Ch'iu-shiu-ch'ueh (the Kujula Kadphises of coins), founded by means of the submission of the other Yueh-chih clans the Kushan Empire."[52]

The earliest documented ruler, and the first one to proclaim himself as a Kushan ruler, was Heraios. He calls himself a "tyrant" in Greek on his coins, and also exhibits skull deformation. He may have been an ally of the Greeks, and he shared the same style of coinage. Heraios may have been the father of the first Kushan emperor Kujula Kadphises.

The Chinese Book of Later Han chronicles then gives an account of the formation of the Kushan empire based on a report made by the Chinese general Ban Yong to the Chinese Emperor c. AD 125:

More than a hundred years later [than the conquest of Bactria by the Yuezhi], the prince [xihou] of Guishuang (Badakhshan) established himself as king, and his dynasty was called that of the Guishuang (Kushan) King. He invaded Anxi (Indo-Parthia), and took the Gaofu (Kabul) region. He also defeated the whole of the kingdoms of Puda (Paktiya) and Jibin (Kapisha and Gandhara). Qiujiuque (Kujula Kadphises) was more than eighty years old when he died. His son, Yangaozhen [probably Vema Tahk (tu) or, possibly, his brother Sadaṣkaṇa ], became king in his place. He defeated Tianzhu [North-western India] and installed Generals to supervise and lead it. The Yuezhi then became extremely rich. All the kingdoms call [their king] the Guishuang [Kushan] king, but the Han call them by their original name, Da Yuezhi.

Diverse cultural influences

In the 1st century BC, the Guishuang (Ch: 貴霜) gained prominence over the other Yuezhi tribes, and welded them into a tight confederation under commander Kujula Kadphises.[59] The name Guishuang was adopted in the West and modified into Kushan to designate the confederation, although the Chinese continued to call them Yuezhi.

Gradually wresting control of the area from the Scythian tribes, the Kushans expanded south into the region traditionally known as Gandhara (an area primarily in Pakistan's Pothowar and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region) and established twin capitals in Begram.[60] and Charsadda, then known as Kapisa and Pushklavati respectively.[59]

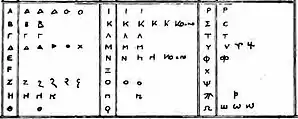

The Kushans adopted elements of the Hellenistic culture of Bactria. They adopted the Greek alphabet to suit their own language (with the additional development of the letter Þ "sh", as in "Kushan") and soon began minting coinage on the Greek model. On their coins they used Greek language legends combined with Pali legends (in the Kharoshthi script), until the first few years of the reign of Kanishka. After the middle of Kanishka's reign, they used Kushan language legends (in an adapted Greek script), combined with legends in Greek (Greek script) and legends in Prakrit (Kharoshthi script).

Obverse: Kanishka standing, clad in heavy Kushan coat and long boots, flames emanating from shoulders, holding a standard in his left hand, and making a sacrifice over an altar. Greek legend:

Basileus Basileon Kanishkoy

"[Coin] of Kanishka, king of kings".

The Kushans "adopted many local beliefs and customs, including Zoroastrianism and the two rising religions in the region, the Greek cults and Buddhism".[60] From the time of Vima Takto, many Kushans started adopting aspects of Buddhist culture, and like the Egyptians, they absorbed the strong remnants of the Greek culture of the Hellenistic Kingdoms, becoming at least partly Hellenised. The great Kushan emperor Vima Kadphises may have embraced Shaivism (a sect of Hinduism), as surmised by coins minted during the period.[14] The following Kushan emperors represented a wide variety of faiths including Buddhism, Zoroastrianism and Shaivism.

The rule of the Kushans linked the seagoing trade of the Indian Ocean with the commerce of the Silk Road through the long-civilized Indus Valley. At the height of the dynasty, the Kushans loosely ruled a territory that extended to the Aral Sea through present-day Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan into northern India.[59]

The loose unity and comparative peace of such a vast expanse encouraged long-distance trade, brought Chinese silks to Rome, and created strings of flourishing urban centers.[59]

Territorial expansion

Rosenfield notes that archaeological evidence of a Kushan rule of long duration is present in an area stretching from Surkh Kotal, Begram, the summer capital of the Kushans, Peshawar, the capital under Kanishka I, Taxila, and Mathura, the winter capital of the Kushans.[66] The Kushans introduced for the first time a form of governance which consisted of Kshatrapas (Brahmi:![]()

![]()

![]() , Kṣatrapa, "Satraps") and Mahakshatrapa (Brahmi:

, Kṣatrapa, "Satraps") and Mahakshatrapa (Brahmi:![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , Mahakṣatrapa, "Great Satraps").[67]

, Mahakṣatrapa, "Great Satraps").[67]

Other areas of probable rule include Khwarezm and its capital city of Toprak-Kala,[66][68] Kausambi (excavations of Allahabad University),[66] Sanchi and Sarnath (inscriptions with names and dates of Kushan kings),[66] Malwa and Maharashtra,[69] and Odisha (imitation of Kushan coins, and large Kushan hoards).[66]

Kushan invasions in the 1st century AD had been given as an explanation for the migration of Indians from the Indian Subcontinent toward Southeast Asia according to proponents of a Greater India theory by 20th-century Indian nationalists. However, there is no evidence to support this hypothesis.[70]

The Rabatak inscription, discovered in 1993, confirms the account of the Hou Hanshu, Weilüe, and inscriptions dated early in the Kanishka era (incept probably AD 127), that large Kushan dominions expanded into the heartland of northern India in the early 2nd century AD. Lines 4 to 7 of the inscription describe the cities which were under the rule of Kanishka,[note 6] among which six names are identifiable: Ujjain, Kundina, Saketa, Kausambi, Pataliputra, and Champa (although the text is not clear whether Champa was a possession of Kanishka or just beyond it).[71][note 5][72][73] The Buddhist text Śrīdharmapiṭakanidānasūtra—known via a Chinese translation made in AD 472—refers to the conquest of Pataliputra by Kanishka.[74] A 2nd century stone inscription by a Great Satrap named Rupiamma was discovered in Pauni, south of the Narmada river, suggesting that Kushan control extended this far south, although this could alternatively have been controlled by the Western Satraps.[75]

In the East, as late as the 3rd century AD, decorated coins of Huvishka were dedicated at Bodh Gaya together with other gold offerings under the "Enlightenment Throne" of the Buddha, suggesting direct Kushan influence in the area during that period.[77] Coins of the Kushans are found in abundance as far as Bengal, and the ancient Bengali state of Samatata issued coins copied from the coinage of Kanishka I, although probably only as a result of commercial influence.[78][76][79] Coins in imitation of Kushan coinage have also been found abundantly in the eastern state of Orissa.[80]

In the West, the Kushan state covered the Pārata state of Balochistan, western Pakistan, Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. Turkmenistan was known for the Kushan Buddhist city of Merv.[66]

Northward, in the 1st century AD, the Kujula Kadphises sent an army to the Tarim Basin to support the city-state of Kucha, which had been resisting the Chinese invasion of the region, but they retreated after minor encounters.[81] In the 2nd century AD, the Kushans under Kanishka made various forays into the Tarim Basin, where they had various contacts with the Chinese. Kanishka held areas of the Tarim Basin apparently corresponding to the ancient regions held by the Yüeh-zhi, the possible ancestors of the Kushan. There was Kushan influence on coinage in Kashgar, Yarkand, and Khotan.[64] According to Chinese chronicles, the Kushans (referred to as Da Yuezhi in Chinese sources) requested, but were denied, a Han princess, even though they had sent presents to the Chinese court. In retaliation, they marched on Ban Chao in AD 90 with a force of 70,000 but were defeated by the smaller Chinese force. Chinese chronicles relate battles between the Kushans and the Chinese general Ban Chao.[73] The Yuezhi retreated and paid tribute to the Chinese Empire. The regions of the Tarim Basin were all ultimately conquered by Ban Chao. Later, during the Yuánchū period (AD 114–120), the Kushans sent a military force to install Chenpan, who had been a hostage among them, as king of Kashgar.[82]

Main Kushan rulers

Kushan rulers are recorded for a period of about three centuries, from circa AD 30 to circa 375, until the invasions of the Kidarites. They ruled around the same time as the Western Satraps, the Satavahanas, and the first Gupta Empire rulers.

Kujula Kadphises (c. 30 – c. 80)

| Kushan emperors 30 CE–350 CE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

...the prince [elavoor] of Guishuang, named thilac [Kujula Kadphises], attacked and exterminated the four other xihou. He established himself as king, and his dynasty was called that of the Guishuang [Kushan] King. He invaded Anxi [Indo-Parthia] and took the Gaofu [Kabul] region. He also defeated the whole of the kingdoms of Puda [Paktiya] and Jibin [Kapisha and Gandhara]. Qiujiuque [Kujula Kadphises] was more than eighty years old when he died."

— Hou Hanshu[57]

These conquests by Kujula Kadphises probably took place sometime between AD 45 and 60 and laid the basis for the Kushan Empire which was rapidly expanded by his descendants.

Kujula issued an extensive series of coins and fathered at least two sons, Sadaṣkaṇa (who is known from only two inscriptions, especially the Rabatak inscription, and apparently never ruled), and seemingly Vima Takto.

Kujula Kadphises was the great-grandfather of Kanishka.

Vima Taktu or Sadashkana (c. 80 – c. 95)

Vima Takto (Ancient Chinese: 閻膏珍 Yangaozhen) is mentioned in the Rabatak inscription (another son, Sadashkana, is mentioned in an inscription of Senavarman, the King of Odi). He was the predecessor of Vima Kadphises, and Kanishka I. He expanded the Kushan Empire into the northwest of South Asia. The Hou Hanshu says:

"His son, Yangaozhen [probably Vema Tahk (tu) or, possibly, his brother Sadaṣkaṇa], became king in his place. He defeated Tianzhu [North-western India] and installed Generals to supervise and lead it. The Yuezhi then became extremely rich. All the kingdoms call [their king] the Guishuang [Kushan] king, but the Han call them by their original name, Da Yuezhi."

— Hou Hanshu[57]

Vima Kadphises (c. 95 – c. 127)

Vima Kadphises (Kushan language: Οοημο Καδφισης) was a Kushan emperor from around AD 95–127, the son of Sadashkana and the grandson of Kujula Kadphises, and the father of Kanishka I, as detailed by the Rabatak inscription.

Vima Kadphises added to the Kushan territory by his conquests in Bactria. He issued an extensive series of coins and inscriptions. He issued gold coins in addition to the existing copper and silver coinage.

Kanishka I (c. 127 – c. 150)

Mahārāja Rājadhirāja Devaputra Kāṇiṣka

"The Great King, King of Kings, Son of God, Kanishka".[83]

Mathura art, Mathura Museum

The rule of Kanishka the Great, fourth Kushan king, lasted for about 23 years from c. AD 127.[84] Upon his accession, Kanishka ruled a huge territory (virtually all of northern India), south to Ujjain and Kundina and east beyond Pataliputra, according to the Rabatak inscription:

In the year one, it has been proclaimed unto India, unto the whole realm of the governing class, including Koonadeano (Kaundiny, Kundina) and the city of Ozeno (Ozene, Ujjain) and the city of Zageda (Saketa) and the city of Kozambo (Kausambi) and the city of Palabotro (Pataliputra) and as far as the city of Ziri-tambo (Sri-Champa), whatever rulers and other important persons (they might have) he had submitted to (his) will, and he had submitted all India to (his) will.

— Rabatak inscription, Lines 4–8

His territory was administered from two capitals: Purushapura (now Peshawar in northwestern Pakistan) and Mathura, in northern India. He is also credited (along with Raja Dab) for building the massive, ancient Fort at Bathinda (Qila Mubarak), in the modern city of Bathinda, Indian Punjab.

The Kushans also had a summer capital in Bagram (then known as Kapisa), where the "Begram Treasure", comprising works of art from Greece to China, has been found. According to the Rabatak inscription, Kanishka was the son of Vima Kadphises, the grandson of Sadashkana, and the great-grandson of Kujula Kadphises. Kanishka's era is now generally accepted to have begun in 127 on the basis of Harry Falk's ground-breaking research.[23][24] Kanishka's era was used as a calendar reference by the Kushans for about a century, until the decline of the Kushan realm.

Huvishka (c. 150 – c. 180)

Huvishka (Kushan: Οοηϸκι, "Ooishki") was a Kushan emperor from the death of Kanishka (assumed on the best evidence available to be in 150) until the succession of Vasudeva I about thirty years later. His rule was a period of retrenchment and consolidation for the Empire. In particular he devoted time and effort early in his reign to the exertion of greater control over the city of Mathura.

Vasudeva I (c. 190 – c. 230)

Vasudeva I (Kushan: Βαζοδηο "Bazodeo", Chinese: 波調 "Bodiao") was the last of the "Great Kushans". Named inscriptions dating from year 64 to 98 of Kanishka's era suggest his reign extended from at least AD 191 to 225. He was the last great Kushan emperor, and the end of his rule coincides with the invasion of the Sasanians as far as northwestern India, and the establishment of the Indo-Sasanians or Kushanshahs in what is nowadays Afghanistan, Pakistan and northwestern India from around AD 240.

Vāsishka (c. 247 – c. 267)

Vāsishka was a Kushan emperor who seems to have had a 20-year reign following Kanishka II. His rule is recorded at Mathura, in Gandhara and as far south as Sanchi (near Vidisa), where several inscriptions in his name have been found, dated to the year 22 (the Sanchi inscription of "Vaksushana" – i.e., Vasishka Kushana) and year 28 (the Sanchi inscription of Vasaska – i.e., Vasishka) of a possible second Kanishka era.[87][88]

Little Kushans (AD 270 – 350)

Following territory losses in the west (Bactria lost to the Kushano-Sasanians), and in the east (loss of Mathura to the Gupta Empire), several "Little Kushans" are known, who ruled locally in the area of Punjab with their capital at Taxila: Vasudeva II (270 – 300), Mahi (300 – 305), Shaka (305 – 335) and Kipunada (335 – 350).[87] They probably were vassals of the Gupta Empire, until the invasion of the Kidarites destroyed the last remains of Kushan rule.[87]

Kushan deities

The Kushan religious pantheon is extremely varied, as revealed by their coins that were made in gold, silver, and copper. These coins contained more than thirty different gods, belonging mainly to their own Iranian, as well as Greek and Indian worlds as well. Kushan coins had images of Kushan Kings, Buddha, and figures from the Indo-Aryan and Iranian pantheons.[90] Greek deities, with Greek names are represented on early coins. During Kanishka's reign, the language of the coinage changes to Bactrian (though it remained in Greek script for all kings). After Huvishka, only two divinities appear on the coins: Ardoxsho and Oesho (see details below).[91][92]

The Iranian entities depicted on coinage include:

- Ardoxsho (Αρδοχþο): Ashi Vanghuhi

- Ashaeixsho (Aþαειχþo, "Best righteousness"): Asha Vahishta

- Athsho (Αθþο, "The Royal fire"): Atar[91]

- Pharro (Φαρρο, "Royal splendour"): Khwarenah

- Lrooaspa (Λροοασπο): Drvaspa

- Manaobago (Μαναοβαγο): Vohu Manah[93]

- Mao (Μαο, the Lunar deity): Mah

- Mithro and variants (Μιθρο, Μιιρο, Μιορο, Μιυρο): Mithra

- Mozdooano (Μοζδοοανο, "Mazda the victorious?"): Mazda *vana[91][94]

- Nana (Νανα, Ναναια, Ναναϸαο): variations of pan-Asiatic Nana, Sogdian Nny, Anahita[91]

- Oado (Οαδο): Vata

- Oaxsho (Oαxþo): "Oxus"

- Ooromozdo (Οορομοζδο): Ahura Mazda

- Ořlagno (Οραλαγνο): Verethragna, the Iranian god of war

- Rishti (Ριϸτι, "Uprightness"): Arshtat[91]

- Shaoreoro (Ϸαορηορο, "Best royal power", Archetypal ruler): Khshathra Vairya[91]

- Tiero (Τιερο): Tir

Representation of entities from Greek mythology and Hellenistic syncretism are:

- Zaoou (Ζαοου):[95] Zeus

- Ēlios (Ηλιος): Helios

- Ēphaēstos (Ηφαηστος): Hephaistos

- Oa nēndo (Οα νηνδο): Nike

- Salēnē (Ϲαληνη):[96][97][98][99] Selene

- Anēmos (Ανημος): Anemos

.jpg.webp)

- Ērakilo (Ηρακιλο): Heracles

- Sarapo (Ϲαραπο): the Greco-Egyptian god Sarapis

.jpg.webp)

The Indic entities represented on coinage include:[100]

- Boddo (Βοδδο): the Buddha

- Shakamano Boddho (Ϸακαμανο Βοδδο): Shakyamuni Buddha

- Metrago Boddo (Μετραγο Βοδδο): the bodhisattava Maitreya

- Maaseno (Μαασηνο): Mahāsena

- Skando-Komaro (Σκανδο-kομαρο): Skanda-Kumara

- Bizago: Viśākha[100]

- Ommo: Umā, the consort of Siva.[100]

- Oesho (Οηϸο): long considered to represent Indic Shiva,[101][102][103] but also identified as Avestan Vayu conflated with Shiva.[104][105]

- Two copper coins of Huvishka bear a 'Ganesa' legend, but instead of depicting the typical theriomorphic figure of Ganesha, have a figure of an archer holding a full-length bow with string inwards and an arrow. This is typically a depiction of Rudra, but in the case of these two coins is generally assumed to represent Shiva.

- Deities on Kushan coinage and seals

Mahasena on a coin of Huvishka

Mahasena on a coin of Huvishka Four-faced Oesho

Four-faced Oesho

Manaobago

Manaobago Pharro

Pharro Ardochsho

Ardochsho Oesho or Shiva

Oesho or Shiva Oesho or Shiva with bull

Oesho or Shiva with bull Skanda and Visakha

Skanda and Visakha Kushan Carnelian seal representing the "ΑΔϷΟ" (adsho Atar), with triratana symbol left, and Kanishka the Great's dynastic mark right

Kushan Carnelian seal representing the "ΑΔϷΟ" (adsho Atar), with triratana symbol left, and Kanishka the Great's dynastic mark right Coin of Kanishka I, with a depiction of the Buddha and legend "Boddo" in Greek script

Coin of Kanishka I, with a depiction of the Buddha and legend "Boddo" in Greek script Herakles.

Herakles. Buddha

Buddha

Kushans and Buddhism

The Kushans inherited the Greco-Buddhist traditions of the Indo-Greek Kingdom they replaced, and their patronage of Buddhist institutions allowed them to grow as a commercial power.[112] Between the mid-1st century and the mid-3rd century, Buddhism, patronized by the Kushans, extended to China and other Asian countries through the Silk Road.

Kanishka is renowned in Buddhist tradition for having convened a great Buddhist council in Kashmir. Along with his predecessors in the region, the Indo-Greek king Menander I (Milinda) and the Indian emperors Ashoka and Harsha Vardhana, Kanishka is considered by Buddhism as one of its greatest benefactors.

During the 1st century AD, Buddhist books were being produced and carried by monks, and their trader patrons. Also, monasteries were being established along these land routes that went from China and other parts of Asia. With the development of Buddhist books, it caused a new written language called Gandhara. Gandhara consists of eastern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan. Scholars are said to have found many Buddhist scrolls that contained the Gandhari language.[113]

The reign of Huvishka corresponds to the first known epigraphic evidence of the Buddha Amitabha, on the bottom part of a 2nd-century statue which has been found in Govindo-Nagar, and now at the Mathura Museum. The statue is dated to "the 28th year of the reign of Huvishka", and dedicated to "Amitabha Buddha" by a family of merchants. There is also some evidence that Huvishka himself was a follower of Mahayana Buddhism. A Sanskrit manuscript fragment in the Schøyen Collection describes Huvishka as one who has "set forth in the Mahāyāna."[114]

The 12th century historical chronicle Rajatarangini mentions in detail the rule of the Kushan kings and their benevolence towards Buddhism:[115][116]

Then there ruled in this very land the founders of cities called after their own appellations the three kings named Huska, Juska and Kaniska (...) These kings albeit belonging to the Turkish race found refuge in acts of piety; they constructed in Suskaletra and other places monasteries, Caityas and similar edificies. During the glorious period of their regime the kingdom of Kashmir was for the most part an appanage of the Buddhists who had acquired lustre by renunciation. At this time since the Nirvana of the blessed Sakya Simha in this terrestrial world one hundred fifty years, it is said, had elapsed. And a Bodhisattva was in this country the sole supreme ruler of the land; he was the illustrious Nagarjuna who dwelt in Sadarhadvana.

Kushan art

The art and culture of Gandhara, at the crossroads of the Kushan hegemony, developed the traditions of Greco-Buddhist art and are the best known expressions of Kushan influences to Westerners. Several direct depictions of Kushans are known from Gandhara, where they are represented with a tunic, belt and trousers and play the role of devotees to the Buddha, as well as the Bodhisattva and future Buddha Maitreya.

According to Benjamin Rowland, the first expression of Kushan art appears at Khalchayan at the end of the 2nd century BC.[118] It is derived from Hellenistic art, and possibly from the art of the cities of Ai-Khanoum and Nysa, and clearly has similarities with the later Art of Gandhara, and may even have been at the origin of its development.[118] Rowland particularly draws attention to the similarity of the ethnic types represented at Khalchayan and in the art of Gandhara, and also in the style of portraiture itself.[118] For example, Rowland find a great proximity between the famous head of a Yuezhi prince from Khalchayan, and the head of Gandharan Bodhisattvas, giving the example of the Gandharan head of a Bodhisattva in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[118] The similarity of the Gandhara Bodhisattva with the portrait of the Kushan ruler Heraios is also striking.[118] According to Rowland the Bactrian art of Khalchayan thus survived for several centuries through its influence in the art of Gandhara, thanks to the patronage of the Kushans.[118]

During the Kushan Empire, many images of Gandhara share a strong resemblance to the features of Greek, Syrian, Persian and Indian figures. These Western-looking stylistic signatures often include heavy drapery and curly hair,[119] representing a composite (the Greeks, for example, often possessed curly hair).

As the Kushans took control of the area of Mathura as well, the Art of Mathura developed considerably, and free-standing statues of the Buddha came to be mass-produced around this time, possibly encouraged by doctrinal changes in Buddhism allowing to depart from the aniconism that had prevailed in the Buddhist sculptures at Mathura, Bharhut or Sanchi from the end of the 2nd century BC.[120] The artistic cultural influence of kushans declined slowly due to Hellenistic Greek and Indian influences.[121]

- Dated Buddhist statuary under the Kushans

Kanishka I:

Kanishka I:

"Kimbell seated Buddha", with inscription "Year 4 of Kanishka" (AD 131).[note 7][124][125] Another similar statue has "Year 32 of Kanishka".[126] Kanishka I:

Kanishka I:

Buddha from Loriyan Tangai with inscription mentioning the "year 318" of the Yavana era (AD 143).[127] Vasudeva I:

Vasudeva I:

Hashtnagar Buddha and its piedestal, inscribed with "year 384" of the Yavana era (c. AD 209).[127]

.jpg.webp) Kanishka II:

Kanishka II:

Statue of Hariti from Skarah Dheri, Gandhara, "Year 399" of the Yavana era (AD 244).[127]

Kushan coinage

The coinage of the Kushans was abundant and an important tool of propaganda in promoting each Kushan ruler.[128] One of the names for Kushan coins was Dinara, which ultimately came from the Roman name Denarius aureus.[128][129][130] The coinage of the Kushans was copied as far as the Kushano-Sasanians in the west, and the kingdom of Samatata in Bengal to the east. The coinage of the Gupta Empire was also initially derived from the coinage of the Kushan Empire, adopting its weight standard, techniques and designs, following the conquests of Samudragupta in the northwest.[131][132][133] The imagery on Gupta coins then became more Indian in both style and subject matter compared to earlier dynasties, where Greco-Roman and Persian styles were mostly followed.[132][134]

It has long been suggested that the gold contained in Kushan coins was ultimately of Roman origin, and that Roman coins were imported as a consequence of trade and melted in India to mint Kushan coins. However, a recent archaeometallurgical study of trace elements through proton activation analysis has shown that Kushan gold contains high concentrations of platinum and palladium, which rules out the hypothesis of a Roman provenance. To this day, the origin of Kushan gold remains unknown.[135]

Contacts with Rome

Several Roman sources describe the visit of ambassadors from the Kings of Bactria and India during the 2nd century, probably referring to the Kushans.[136]

Historia Augusta, speaking of Emperor Hadrian (117–138) tells:[136]

Reges Bactrianorum legatos ad eum, amicitiae petendae causa, supplices miserunt "The kings of the Bactrians sent supplicant ambassadors to him, to seek his friendship."[136]

Also in 138, according to Aurelius Victor (Epitome‚ XV, 4), and Appian (Praef., 7), Antoninus Pius, successor to Hadrian, received some Indian, Bactrian, and Hyrcanian ambassadors.[136]

Some Kushan coins have an effigy of "Roma", suggesting a strong level of awareness and some level of diplomatic relations.[136]

The summer capital of the Kushan Empire in Begram has yielded a considerable amount of goods imported from the Roman Empire—in particular, various types of glassware. The Chinese described the presence of Roman goods in the Kushan realm:

"Precious things from Da Qin [the Roman Empire] can be found there [in Tianzhu or Northwestern India], as well as fine cotton cloths, fine wool carpets, perfumes of all sorts, sugar candy, pepper, ginger, and black salt."

— Hou Hanshu[137]

Parthamaspates of Parthia, a client of Rome and ruler of the kingdom of Osroene, is known to have traded with the Kushan Empire, goods being sent by sea and through the Indus River.[138]

Contacts with China

During the 1st and 2nd century AD, the Kushan Empire expanded militarily to the north, putting them at the center of the profitable Central Asian commerce. They are related to have collaborated militarily with the Chinese against nomadic incursion, particularly when they allied with the Han dynasty general Ban Chao against the Sogdians in 84, when the latter were trying to support a revolt by the king of Kashgar.[139] Around 85, they also assisted the Chinese general in an attack on Turpan, east of the Tarim Basin.

In recognition for their support to the Chinese, the Kushans requested a Han princess, but were denied,[139][141] even after they had sent presents to the Chinese court. In retaliation, they marched on Ban Chao in 86 with a force of 70,000, but were defeated by a smaller Chinese force.[139][141] The Yuezhi retreated and paid tribute to the Chinese Empire during the reign of emperor He of Han (89–106).

The Kushans are again recorded to have sent presents to the Chinese court in 158–159 during the reign of Emperor Huan of Han.

Following these interactions, cultural exchanges further increased, and Kushan Buddhist missionaries, such as Lokaksema, became active in the Chinese capital cities of Luoyang and sometimes Nanjing, where they particularly distinguished themselves by their translation work. They were the first recorded promoters of Hinayana and Mahayana scriptures in China, greatly contributing to the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism.

Decline

Kushano-Sassanians

After the death of Vasudeva I in 225, the Kushan empire split into western and eastern halves. The Western Kushans (in Afghanistan) were soon subjugated by the Persian Sasanian Empire and lost Sogdiana, Bactria, and Gandhara to them. The Sassanian king Shapur I (240–270) claims in his Naqsh-e Rostam inscription possession of the territory of the Kushans (Kūšān šahr) as far as "Purushapura" (Peshawar), suggesting he controlled Bactria and areas as far as the Hindu-Kush or even south of it:[142]

I, the Mazda-worshipping lord, Shapur, king of kings of Iran and An-Iran... (I) am the Master of the Domain of Iran (Ērānšahr) and possess the territory of Persis, Parthian... Hindestan, the Domain of the Kushan up to the limits of Paškabur and up to Kash, Sughd, and Chachestan.

— Shapur I's inscription at the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht, Naqsh-e Rostam[142]

This is also confirmed by the Rag-i-Bibi inscription in modern Afghanistan.[142]

The Sasanians deposed the Western dynasty and replaced them with Persian vassals known as the Kushanshas (in Bactrian on their coinage: KΟÞANΟ ÞAΟ Koshano Shao)[143] also called Indo-Sasanians or Kushano-Sasanians. The Kushano-Sasanians ultimately became very powerful under Hormizd I Kushanshah (277–286) and rebelled against the Sasanian Empire, while continuing many aspects of the Kushan culture, visible in particular in their titulature and their coinage.[144]

"Little Kushans" and Gupta suzerainty

The Eastern Kushan kingdom, also known as the "Little Kushans", was based in the Punjab. Around 270 their territories on the Gangetic plain became independent under local dynasties such as the Yaudheyas. Then in the mid-4th century they were subjugated by the Gupta Empire under Samudragupta.[148] In his inscription on the Allahabad pillar Samudragupta proclaims that the Dēvaputra-Shāhi-Shāhānushāhi (referring to the last Kushan rulers, being a deformation of the Kushan regnal titles Devaputra, Shao and Shaonanoshao: "Son of God, King, King of Kings") are now under his dominion, and that they were forced to "self-surrender, offering (their own) daughters in marriage and a request for the administration of their own districts and provinces".[149][148][150] This suggests that by the time of the Allahabad inscription the Kushans still ruled in Punjab, but under the suzerainty of the Gupta Emperor.[148]

Numimastics indicate that the coinage of the Eastern Kushans was much weakened: silver coinage was abandoned altogether, and gold coinage was debased. This suggests that the Eastern Kushans had lost their central trading role on the trade routes that supplied luxury goods and gold.[148] Still, the Buddhist art of Gandhara continued to flourish, and cities such as Sirsukh near Taxila were established.[148]

Sasanian, Kidarite and Alchon invasions

In the east around 350, Shapur II regained the upper hand against the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom and took control of large territories in areas now known as Afghanistan and Pakistan, possibly as a consequence of the destruction of the Kushano-Sasanians by the Chionites.[151] The Kushano-Sasanian still ruled in the north. Important finds of Sasanian coinage beyond the Indus river in the city of Taxila only start with the reigns of Shapur II (r.309-379) and Shapur III (r.383-388), suggesting that the expansion of Sasanian control beyond the Indus was the result of the wars of Shapur II "with the Chionites and Kushans" in 350-358 as described by Ammianus Marcellinus.[152] They probably maintained control until the rise of the Kidarites under their ruler Kidara.[152]

In 360 a Kidarite Hun named Kidara overthrew the Kushano-Sasanians and remnants of the old Kushan dynasty, and established the Kidarite Kingdom. The Kushan style of Kidarite coins indicates they claimed Kushan heritage. The Kidarite seem to have been rather prosperous, although on a smaller scale than their Kushan predecessors. East of the Punjab, the former eastern territories of the Kushans were controlled by the mighty Gupta Empire.

The remnants of Kushan culture under the Kidarites in the northwest were ultimately wiped out in the end of the 5th century by the invasions of the Alchon Huns (sometimes considered as a branch of the Hephthalites), and later the Nezak Huns.

Rulers

One of the most recent list of rulers with dates is as follows:[153]

- Heraios (c. 1 – 30), first king to call himself "Kushan" on his coinage

- "Great Kushans";

- Kujula Kadphises (c. 50 – c. 90)

- Vima Takto (c. 90 – c. 113), alias Soter Megas or "Great Saviour."

- Vima Kadphises (c. 113 – c. 127) First great Kushan Emperor

- Kanishka the Great (127 – c. 151)

- Huvishka (c. 151 – c. 190)

- Vasudeva I (c. 190 – 230) Last great Kushan Emperor

- Kanishka II (c. 230 – 247)

- Vashishka (c. 247 – 267)

- "Little Kushans";

See also

Notes

- The Kushans at first retained the Greek language for administrative purposes but soon began to use Bactrian. The Bactrian Rabatak inscription (discovered in 1993 and deciphered in 2000) records that the Kushan king Kanishka the Great (c. 127 AD), discarded Greek (Ionian) as the language of administration and adopted Bactrian ("Arya language").[10]

- The Pali word vaṃśa (dynasty) affixed to Gushana (Kushana), i.e. Gushana-vaṃśa (Kushan dynasty) appears on a dedicatory inscription at Manikiala stupa.[11]

- which began about 127 CE.[23][24][25]

- For example, the 12th century historical chronicle from Kashmir, the Rajatarangini, describes the Kushans as Turushka (तुरुष्क).

- See also the analysis of Sims-Williams & Cribb (1995–1996), specialists of the field, who had a central role in the decipherment.

- For a translation of the full text of the Rabatak inscription see: Mukherjee (1995). This translation is quoted in: Goyal (2005), p. 88.

- Seated Buddha with inscription starting with

𑁕 Maharajasya Kanishkasya Sam 4 "Year 4 of the Great King Kanishka".

𑁕 Maharajasya Kanishkasya Sam 4 "Year 4 of the Great King Kanishka".

References

- Romila Thapar (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8.

- Burton Stein (2010). A History of India. John Wiley & Sons. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1.

- Peter Robb (2011). A History of India. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-230-34549-2.

- Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2016). A History of India. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-24212-3.

- Di Castro, Angelo Andrea; Hope, Colin A. (2005). "The Barbarisation of Bactria". Cultural Interaction in Afghanistan c 300 BCE to 300 CE. Melbourne: Monash University Press. pp. 1–18, map visible online page 2 of Hestia, a Tabula Iliaca and Poseidon's trident. ISBN 978-1876924393.

- Romila Thapar (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8.

- Burton Stein (2010). A History of India. John Wiley & Sons. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1.

- Peter Robb (2011). A History of India. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-230-34549-2.

- Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2016). A History of India. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-24212-3.

- Falk 2001, p. 133.

- Rosenfield 1967, pp. 7 & 8.

- Wurm, Stephen A.; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tryon, Darrell T. (11 February 2011). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Vol I: Maps. Vol II: Texts. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-081972-4.

- Liu 2010, p. 61.

- Bopearachchi 2007, p. 45.

- Golden 1992, p. 56.

- "Afghanistan: Central Asian and Sassanian Rule, ca. 150 B.C.-700 A.D." Library of Congress Country Studies. 1997. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Taagepera, Rein (1979). "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.". Social Science History. 3 (3/4): 132. doi:10.2307/1170959. JSTOR 1170959.

- Rosenfield 1967, p. 7

- Anonymous. "The History of Pakistan: The Kushans". Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World. The mission of Sung-Yun and Hwei-Săng [by Hsüan-chih Yang] Ta-T'ang si-yu-ki. Books 1–5. Translated by Samuel Beal. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. 1906.

- Hill 2009, pp. 29, 318–350.

- Falk 2001, pp. 121–136.

- Falk 2004, pp. 167–176.

- Hill 2009, pp. 29, 33, 368–371.

- Runion, Meredith L. (2007). The history of Afghanistan. Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-313-33798-7.

The Yuezhi people conquered Bactria in the second century BCE. and divided the country into five chiefdoms, one of which would become the Kushan Empire. Recognizing the importance of unification, these five tribes combined under the one dominate Kushan tribe, and the primary rulers descended from the Yuezhi.

- Liu, Xinru (2001). "The Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Interactions in Eurasia". In Adas, Michael (ed.). Agricultural and pastoral societies in ancient and classical history. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-56639-832-9.

- Narain 1990, pp. 152–155 "[W]e must identify them [Tocharians] with the Yueh-chih of the Chinese sources... [C]onsensus of scholarly opinion identifies the Yueh-chih with the Tokharians... [T]he Indo-European ethnic origin of the Yuehchih = Tokharians is generally accepted... Yueh-chih = Tokharian people... Yueh-chih = Tokharians..."

- Beckwith 2009, p. 380 "The identity of the Tokharoi and Yüeh-chih people is quite certain, and has been clear for at least half a century, though this has not become widely known outside the tiny number of philologists who work on early Central Eurasian and early Chinese history and linguistics."

- Pulleyblank 1966, pp. 9–39

- Mallory 1997, pp. 591–593 "[T]he Tocharians have frequently been identified in Chinese historical sources as a people known as the Yuezhi..."

- Loewe & Shaughnessy 1999, pp. 87–88 "Pulleyblank has identified the Yuezhi... Wusun... the Dayuan... the Kangju... and the people of Yanqi... all names occurring in the Chinese historical sources for the Han dynasty, as Tocharian speakers."

- Panel with the god Shiva/Oesho and worshiper. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Masson, V. M.; Harmatta, J.; Puri, Baij Nath; Etemadi, G. F.; Litvinskiĭ, B. A. (1992–2005). History of civilizations of Central Asia. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 317–318. ISBN 92-3-102719-0. OCLC 28186754.

- Grenet, Frantz (2015). "Zoroastrianism among the Kushans". In Falk, Harry (ed.). Kushan histories. Literary sources and selected papers from a symposium at Berlin, December 5 to 7, 2013. Bremen: Hempen Verlag.

- Daniélou, Alain (2003). A Brief History of India. Simon and Schuster. p. 111. ISBN 9781594777943.

- Hill 2009, p. 36 and notes.

- Yatsenko, Sergey A. (2012). "Yuezhi on Bactrian Embroidery from Textiles Found at Noyon uul, Mongolia" (PDF). The Silk Road. 10.

- Francfort, Henri-Paul (1 January 2020). "Sur quelques vestiges et indices nouveaux de l'hellénisme dans les arts entre la Bactriane et le Gandhāra (130 av. J.-C.-100 apr. J.-C. environ)". Journal des Savants: 26–27.

- "Kushan Empire (ca. 2nd century B.C.–3rd century A.D.) | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Roux 1997, p. 90 "They are, by almost unanimous opinion, Indo-Europeans, probably the most oriental of those who occupied the steppes."

- Mallory & Mair 2008, pp. 270–297.

- Enoki, Koshelenko & Haidary 1994, pp. 171–183; Puri 1994, pp. 184–191

- Girshman, Roman. "Ancient Iran: The movement of Iranian peoples". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

At the end of the 3rd century, there began in Chinese Turkistan a long migration of the Yuezhi, an Iranian people who invaded Bactria about 130 bc, putting an end to the Greco-Bactrian kingdom there. (In the 1st century bc they created the Kushān dynasty, whose rule extended from Afghanistan to the Ganges River and from Russian Turkistan to the estuary of the Indus.)

- Mallory & Mair 2008, p. 318.

- Loewe, Michael A.N. (1979). "Introduction". In Hulsewé, Anthony François Paulus (ed.). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage: 125 BC – AD 23; an Annotated Translation of Chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. Brill. pp. 1–70. ISBN 978-90-04-05884-2. pp. 23–24.

- Banerjee, Gauranga Nath (1920). Hellenism in ancient India. Calcutta: Published by the Author; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 92.

- Wink 2002, p. 57.

- Rajatarangini Pandit, Ranjit Sitaram (1935). River Of Kings (rajatarangini). pp. I168–I173.

Then there ruled in this very land the founders of cities called after their own appellations the three kings named Huska, Juska and Kaniska (...) These kings albeit belonging to the Turkish race found refuge in acts of piety; they constructed in Suskaletra and other places monasteries, Caityas and similar edificies.

- Rosenfield 1967, p. 8

- KHALCHAYAN – Encyclopaedia Iranica. Figure 1.

- Grousset 1970, pp. 31-32

- Lebedynsky 2006, p. 62.

- Lebedynsky 2006, p. 15.

- Fedorov, Michael (2004). "On the origin of the Kushans with reference to numismatic and anthropological data" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society. 181 (Autumn): 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- Abdullaev, Kazim (2007). "Nomad Migration in Central Asia (in After Alexander: Central Asia before Islam)". Proceedings of the British Academy. 133: 89.

The knights in chain-mail armour have analogies in the Khalchayan reliefs depicting a battle of the Yuezhi against a Saka tribe (probably the Sakaraules). Apart from the chain-mail armour worn by the heavy cavalry of the enemies of the Yuezhi, the other characteristic sign of these warriors is long side-whiskers (...) We think it is possible to identify all these grotesque personages with long side-whiskers as enemies of the Yuezhi and relate them to the Sakaraules (...) Indeed these expressive figures with side-whiskers differ greatly from the tranquil and majestic faces and poses of the Yuezhi depictions.

- Hill 2009, p. 29.

- Chavannes 1907, pp. 190–192.

- Benjamin, Craig (16 April 2015). The Cambridge World History: Volume 4, A World with States, Empires and Networks 1200 BCE–900 CE. Cambridge University Press. p. 477 ff. ISBN 978-1-316-29830-5.

It is generally agreed that the Kushans were one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi...

- Starr, S. Frederick (2013). Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia's Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 53.

- O'Brien, Patrick Karl; Press, Oxford University (2002). Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-19-521921-0.

- Goyal 2005, p. 93. "The Rabatak inscription claims that in the year 1 Kanishka I's authority was proclaimed in India, in all the satrapies and in different cities like Koonadeano (Kundina), Ozeno (Ujjain), Kozambo (Kausambi), Zagedo (Saketa), Palabotro (Pataliputra), and Ziri-Tambo (Janjgir-Champa). These cities lay to the east and south of Mathura, up to which locality Wima had already carried his victorious arm. Therefore they must have been captured or subdued by Kanishka I himself."

- Mukherjee, B.N. (1995). "The Great Kushana Testament". Indian Museum Bulletin. Calcutta.

- Cribb, Joe (1984). "The Sino-Kharosthi coins of Khotan part 2". Numismatic Chronicle. pp. 129–152.

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 145, map XIV.1(g). ISBN 0226742210.

- Rosenfield 1993, p. 41.

- Sailendra Nath Sen 1999, p. 188.

- Basham, Arthur Llewellyn (1968). Papers on the Date of Kaniṣka: Submitted to the Conference on the Date of Kaniṣka, London, 20-22 April 1960. Brill Archive. p. 414.

- Rosenfield 1993, p. 41. "Malwa and Maharashtra, for which it is speculated that the Kushans had an alliance with the Western Kshatrapas".

- Hall, D.G.E. (1981). A History of South-East Asia, Fourth Edition. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd. p. 17. ISBN 0-333-24163-0.

- Goyal 2005, p. 93. "The Rabatak inscription claims that in the year 1 Kanishka I's authority was proclaimed in India, in all the satrapies and in different cities like Koonadeano (Kundina), Ozeno (Ujjain), Kozambo (Kausambi), Zagedo (Saketa), Palabotro (Pataliputra) and Ziri-Tambo (Janjgir-Champa). These cities lay to the east and south of Mathura, up to which locality Wima had already carried his victorious arm. Therefore they must have been captured or subdued by Kanishka I himself."

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas. "Bactrian Documents from Ancient Afghanistan". Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

- Rezakhani 2017b, p. 201.

- Puri 1999, p. 258.

- Mukherjee, Bratindra Nath (1988). The rise and fall of the Kushāṇa Empire. p. 269. ISBN 9780836423938.

- "Samatata coin". The British Museum.

- British Museum display, Asian Art room.

- Sengupta, Nitish (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin UK. p. 39. ISBN 978-81-8475-530-5.

- Numismatic Digest. Numismatic Society of Bombay. 2012. p. 29.

As far as gold coins in Bengal are concerned it was Samatata or South-eastern Bengal which issued gold coins ... This trend of imitating Kushan gold continued and had major impact on the currency pattern of this south-eastern zone.

- Ray, N. R. (1982). Sources of the History of India: Bihar, Orissa, Bengal, Manipur, and Tripura. Institute of Historical Studies. p. 194.

A large number of Kushan and Puri Kushan coins have been discovered from different parts of Orissa. Scholars have designated the Puri Kushan coins as the Oriya Kushan coins. Though the coins are the imitations of Kushan coins they have been abundantly found from different parts of Orissa.

- Grousset 1970, pp. 45–46.

- Hill 2009, p. 43.

- Puri, Baij Nath (1965). India under the Kushāṇas. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Bracey, Robert (2017). "The Date of Kanishka since 1960". Indian Historical Review. 44 (1): 21–61. doi:10.1177/0376983617694717. S2CID 149016806.

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 25, 145. ISBN 0226742210.

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 25, 145. ISBN 0226742210.

- Rezakhani 2017b, p. 203.

- Rosenfield 1967, p. 57

- Marshak, Boris; Grenet, Frantz (2006). "Une peinture kouchane sur toile". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 150 (2): 957. doi:10.3406/crai.2006.87101.

- Liu 2010, p. 47.

- Harmatta 1999, pp. 327–328

- Boyce, Mary (2001). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Psychology Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-415-23902-8.

- Harmatta 1999, p. 324.

- Jongeward, David; Cribb, Joe (2014). Kushan, Kushano-Sasanian, and Kidarite Coins A Catalogue of Coins From the American Numismatic Society (PDF). New York: THE AMERICAN NUMISMATIC SOCIETY. p. Front page illustration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- "Kujula Kadphises coin". The British Museum.

- Dani, A. H.; Asimov, M. S.; Litvinsky, B. A.; Zhang, Guang-da; Samghabadi, R. Shabani; Bosworth, C. E. (1 January 1994). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A. UNESCO. p. 321. ISBN 978-92-3-102846-5.

- The Cambridge Shorter History of India. CUP Archive. p. 77.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 199. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 377. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- Harmatta 1999, p. 326. "Also omitted is the ancient Iranian war god Orlagno, whose place and function are occupied by a group of Indian war gods, Skando (Old Indian Skanda), Komaro (Old Indian Kumara), Maaseno (Old Indian Mahāsena), Bizago (Old Indian Viśākha), and even Ommo (Old Indian Umā), the consort of Siva. Their use as reverse types of Huvishka I is clear evidence for the new trends in religious policy of the Kushan king, which was possibly influenced by enlisting Indian warriors into the Kushan army during the campaign against Pataliputra."

- Sivaramamurti 1976, p. 56-59.

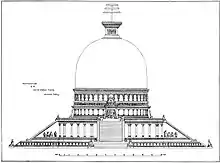

- Loeschner, Hans (July 2012). "The Stūpa of the Kushan Emperor Kanishka the Great" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 227: 11.

- Bopearachchi 2007, pp. 41–53.

- Sims-Williams, Nicolas. "Bactrian Language". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 3. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Bopearachchi 2003. Cites H. Humbach, 1975, p.402-408. K.Tanabe, 1997, p.277, M.Carter, 1995, p.152. J.Cribb, 1997, p.40.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition.

- "Panel fragment with the god Shiva/Oesho". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Fleet, J.F. (1908). "The Introduction of the Greek Uncial and Cursive Characters into India". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 1908: 179, note 1. JSTOR 25210545.

The reading of the name of the deity on this coin is very much uncertain and disputed (Riom, Riddhi, Rishthi, Rise....)

- Shrava, Satya (1985). The Kushāṇa Numismatics. Pranava Prakashan. p. 29.

The name Riom as read by Gardner, was read by Cunningham as Ride, who equated it with Riddhi, the Indian goddess of fortune. F.W. Thomas has read the name as Rhea

- Perkins, J. (2007). Three-headed Śiva on the Reverse of Vima Kadphises's Copper Coinage. South Asian Studies, 23(1), 31–37

- Fitzwilliam Museum (1992). Errington, Elizabeth (ed.). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ancient India and Iran Trust. p. 87. ISBN 9780951839911.

- Liu 2010, p. 42.

- Liu 2010, p. 58.

- Neelis, Jason. Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks. 2010. p. 141

- Sailendra Nath Sen 1999, pp. 199–200.

- Mahajan, V.D (2016). Ancient India. S. Chand Publishing. p. 330. ISBN 978-93-5253-132-5.

- Pandit, Ranjit Sitaram (1935). River Of Kings (rajatarangini). p. I168–I173.

- Rowland, Benjamin (1971). "Graeco-Bactrian Art and Gandhāra: Khalchayan and the Gandhāra Bodhisattvas". Archives of Asian Art. 25: 29–35. ISSN 0066-6637. JSTOR 20111029.

- Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art: guide to the collection. [Birmingham, Ala]: Birmingham Museum of Art. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5.

- Stoneman, Richard (2019). The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press. pp. 439–440. ISBN 9780691185385.

- Sailendra Nath Sen 1999, p. 202.

- Ghosh, N. N. (1935). Early History of Kausambi. Allahabad Law Journal Press. p. xxi.

- Epigraphia Indica 8 p.179

- "Seated Buddha with Two Attendants, A.D. 82". Kimbell Art Museum.

- Asian Civilisations Museum (Singapore) (2007). Krishnan, Gauri Parimoo (ed.). The Divine Within: Art & Living Culture of India & South Asia. World Scientific Pub. p. 113. ISBN 9789810567057.

The Buddhist Triad, from Haryana or Mathura, Year 4 of Kaniska (ad 82). Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth.

- Behrendt, Kurt A. (2007). The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 48, Fig. 18. ISBN 9781588392244.

- Rhi, Juhyung (2017). Problems of Chronology in Gandharan. Positioning Gandharan Buddhas in Chronology (PDF). Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology. pp. 35–51.

- Sen, Sudipta (2019). Ganges: The Many Pasts of an Indian River. Yale University Press. p. 205. ISBN 9780300119169.

- Vanaja, R. (1983). Indian Coinage. National Museum.

Known by the term Dinars in early Gupta inscriptions, their gold coinage was based on the weight standard of the Kushans i.e. 8 gms/120 grains. It was replaced in the time of Skandagupta by a standard of 80 ratis or 144 grains.

- Mookerji, Radhakumud (1997). The Gupta Empire. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 31. ISBN 9788120804401.

- Gupta inscriptions using the term "Dinara" for money: No 5-9, 62, 64 in Fleet, John Faithfull (1960). Inscriptions Of The Early Gupta Kings And Their Successors.

- Mookerji, Radhakumud (1997). The Gupta Empire. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 30. ISBN 9788120804401.

- Higham, Charles (2014). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Infobase Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 9781438109961.

- Pal, Pratapaditya (1986). Indian Sculpture. Volume I: Circa 500 B.C.-A.D. 700. Los Angeles County Museum of Art with University of California Press. pp. 73, 78. ISBN 9780520059917.

- Reden, Sitta (2 December 2019). Handbook of Ancient Afro-Eurasian Economies: Volume 1: Contexts. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 505. ISBN 978-3-11-060494-8.

- McLaughlin, Raoul (2010). Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India and China. A&C Black. p. 131. ISBN 9781847252357.

- Hill 2009, p. 31.

- Ellerbrock, Uwe (2021). The Parthians: The Forgotten Empire. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-000-35848-3.

- de Crespigny, Rafe. (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. page 5-6. ISBN 90-04-15605-4.

- Joe Cribb, 1974, "Chinese lead ingots with barbarous Greek inscriptions in Coin Hoards" pp.76–8

- Torday, Laszlo. (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham: The Durham Academic Press. page 393. ISBN 1-900838-03-6.

- Rezakhani 2017b, pp. 202–203.

- Rezakhani 2017b, p. 204.

- Rezakhani 2017b, pp. 200–210.

- Eraly, Abraham (2011). The First Spring: The Golden Age of India. Penguin Books India. p. 38. ISBN 9780670084784.

- Errington, Elizabeth; Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh (2007). From Persepolis to the Punjab: Exploring Ancient Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. British Museum Press. p. 88. ISBN 9780714111650.

In the Punjab the stylistic progression of the gold series from Kushan to Kidarite is clear: imitation staters were issued first in the name of Samudragupta, then by Kirada, 'Peroz' and finally Kidara

- Cribb, Joe (January 2010). "The Kidarites, the numismatic evidence". Coins, Art and Chronology II: 101.

- Dani, Litvinsky & Zamir Safi 1996, pp. 165–166

- Lines 23-24 of the Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta: "Self-surrender, offering (their own) daughters in marriage and a request for the administration of their own districts and provinces through the Garuḍa badge, by the Dēvaputra-Shāhi-Shāhānushāhi and the Śaka lords and by (rulers) occupying all Island countries, such as Siṁhala and others."

- Cribb, Joe; Singh, Karan (Winter 2017). "Two Curious Kidarite Coin Types From 3th Century Kashmir". JONS. 230: 3.

- Rezakhani 2017a, p. 85.

- Ghosh, Amalananda (1965). Taxila. CUP Archive. pp. 790–791.

- Jongeward, David; Cribb, Joe (2014). Kushan, Kushano-Sasanian, and Kidarite Coins A Catalogue of Coins From the American Numismatic Society by David Jongeward and Joe Cribb with Peter Donovan. p. 4.

- The Glorious History of Kushana Empire, Adesh Katariya, 2012, p.69

Sources

| History of India |

|---|

|

| History of Afghanistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

- Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The Ancient Past. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35616-9.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2994-1.

- Benjamin, Craig (2007). The Yuezhi: Origin, Migration and the Conquest of Northern Bactria. ISD. ISBN 978-2-503-52429-0.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (2003). De l'Indus à l'Oxus, Archéologie de l'Asie Centrale (in French). Lattes: Association imago-musée de Lattes. ISBN 2-9516679-2-2.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (2007). "Some Observations on the Chronology of the Early Kushans". In Gyselen, Rika (ed.). Des Indo-Grecs aux Sassanides: données pour l'histoire et la géographie historique. Vol. XVII. Group pour l'Etude de la Civilisation du Moyen-Orient.

- Chavannes, Édouard (1906). Trois Généraux Chinois de la dynastie des Han Orientaux. Pan Tch'ao (32–102 p.C.); – son fils Pan Yong; – Leang K'in (112 p.C.). Chapitre LXXVII du Heou Han chou. T'oung pao 7.

- Chavannes, Édouard (1907). Les pays d'occident d'après le Heou Han chou. T'oung pao 8. pp. 149–244.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Litvinsky, Boris Abramovich; Zamir Safi, M. H. "Eastern Kushans, Kidarines in Gandhara ans Kashmir, and Later Hephthalites". In Litvinsky (1996), pp. 163–184.

- Dorn'eich, Chris M. (2008). Chinese sources on the History of the Niusi-Wusi-Asi (oi)-Rishi (ka)-Arsi-Arshi-Ruzhi and their Kueishuang-Kushan Dynasty. Shiji 110/Hanshu 94A: The Xiongnu: Synopsis of Chinese original Text and several Western Translations with Extant Annotations. Berlin. To read or download go to:

- Enoki, K.; Koshelenko, G. A.; Haidary, Z. "The Yu'eh-chih and their migrations". In Harmatta, Puri & Etemadi (1994), pp. 165–183.

- Faccenna, Domenico (1980). Butkara I (Swāt, Pakistan) 1956–1962, Volume III 1 (in English). Rome: IsMEO (Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente).

- Falk, Harry (1995–1996). Silk Road Art and Archaeology IV.

- Falk, Harry (2001). "The yuga of Sphujiddhvaja and the era of the Kuṣāṇas". Silk Road Art and Archaeology VII. pp. 121–136.

- Falk, Harry (2004). "The Kaniṣka era in Gupta records". Silk Road Art and Archaeology X. pp. 167–176.

- Foucher, M. A. 1901. "Notes sur la geographie ancienne du Gandhâra (commentaire à un chaptaire de Hiuen-Tsang)." BEFEO No. 4, Oct. 1901, pp. 322–369.

- Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Goyal, S. R. (2005). Ancient Indian Inscriptions. Jodhpur, India: Kusumanjali Book World.

- Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Hargreaves, H. (1910–11). "Excavations at Shāh-jī-kī Dhērī"; Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 25–32.

- Harmatta, János. "Religions in the Kushan Empire". In Harmatta, Puri & Etemadi (1999), pp. 313–330.

- Harmatta, János; Puri, B. N.; Etemadi, G. F., eds. (1994). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Volume II The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-102846-5. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Harmatta, János; Puri, B. N.; Etemadi, G. F., eds. (1999) [1994]. History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Volume II The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8-1208-1408-0. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE. BookSurge. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hoey, W. "The Word Kozola as Used of Kadphises on Ku͟s͟hān Coins." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1902, pp. 428–429. JSTOR 25208419.

- Iloliev, A. "King of Men: ῾Ali ibn Abi Talib in Pamiri Folktales." Journal of Shi'a Islamic Studies, vol. 8 no. 3, 2015, pp. 307–323. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/isl.2015.0036.

- Kennedy, J. "The Later Kushans." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1913, pp. 1054–1064. JSTOR 25189078.

- Konow, Sten, ed. 1929. Kharoshthī Inscriptions with Exception of those of Asoka. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. II, Part I. Reprint: Indological Book House, Varanasi, 1969.

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav (2006). Les Saces. Paris: Editions Errance. ISBN 2-87772-337-2.

- Lerner, Martin (1984). The flame and the lotus: Indian and Southeast Asian art from the Kronos collections. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-374-7.

- Litvinsky, Boris Abramovich, ed. (1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Volume III The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 9789231032110.

- Liu, Xinru (Fall 2001). "Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan: Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies". Journal of World History. University of Hawaii Press. 12 (2): 261–292. doi:10.1353/jwh.2001.0034. S2CID 162211306.

- Liu, Xinru (2010). The Silk Road in World History. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1999). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308. ISBN 0-521-47030-7.

- Mallory, J. P. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-884964-98-2.

- Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2008). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28372-1.

- Masson, V. M. "The Forgotten Kushan Empire: New Discoveries at Zar-Tepe." Archaeology, vol. 37, no. 1, 1984, pp. 32–37. JSTOR 41728802.

- Narain, A. K. (1990). "Indo-Europeans in Central Asia". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–177. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521243049.007. ISBN 978-1-139-05489-8.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1966). "Chinese and Indo-Europeans". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 98 (1/2): 9–39. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00124566. JSTOR 25202896. S2CID 144332029.

- Puri, Baij Nath. "The Sakas and Indo-Parthians". In Harmatta, Puri & Etemadi (1994), pp. 184–201.

- Puri, Baij Nath. "The Kushans". In Harmatta, Puri & Etemadi (1999), pp. 247–264.

- "Red Sandstone Railing Pillar." The British Museum Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 1/2, 1965, pp. 64–64. JSTOR 4422925.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017a). "East Iran in Late Antiquity". ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 978-1-4744-0030-5. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g04zr8. (registration required)

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017b). "From the Kushans to the Western Turks". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236. ISBN 978-0-692-86440-1.

- Rife, J. L. "The Making of Roman India by Grant Parker (review)." American Journal of Philology, vol. 135 no. 4, 2014, pp. 672–675. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/ajp.2014.0046.

- Rosenfield, John M. (1967). The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. University of California Press.

- Rosenfield, John M. (1993). The Dynastic Art of the Kushans. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 81-215-0579-8.

- Roux, Jean-Paul (1997). L'Asie Centrale, Histoire et Civilization [Central Asia: History and Civilization] (in French). Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-59894-9.

- Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- Sarianidi, Viktor. 1985. The Golden Hoard of Bactria: From the Tillya-tepe Excavations in Northern Afghanistan. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas; Cribb, Joe. "A new Bactrian inscription of Kanishka the Great". In Falk (1995–1996), pp. 75–142.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas. 1998. "Further notes on the Bactrian inscription of Rabatak, with an Appendix on the names of Kujula Kadphises and Vima Taktu in Chinese." Proceedings of the Third European Conference of Iranian Studies Part 1: Old and Middle Iranian Studies. Edited by Nicholas Sims-Williams. Wiesbaden. pp. 79–93.

- Sivaramamurti, C. (1976). Śatarudrīya: Vibhūti of Śiva's Iconography. Delhi: Abhinav Publications.

- Spooner, D. B. (1908–09). "Excavations at Shāh-jī-kī Dhērī."; Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 38–59.

- Watson, Burton. Trans. 1993. Records of the Grand Historian of China: Han Dynasty II. Translated from the Shiji of Sima Qian. Chapter 123: "The Account of Dayuan", Columbia University Press. Revised Edition. ISBN 0-231-08166-9; ISBN 0-231-08167-7 (pbk.)

- Wink, André (2002). Al-Hind: The Slavic Kings and the Islamic conquest, 11th-13th centuries. BRILL.

- Zürcher, E. (1968). "The Yüeh-chih and Kaniṣka in the Chinese sources". In Basham, A. L. (ed.). Papers on the Date of Kaniṣka. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 346–393.

External links

- Kushan dynasty in Encyclopædia Britannica

- Metropolitan Museum capsule history

- New documents help fix controversial Kushan dating at the Wayback Machine (archived 4 February 2005)

- Coins of the Kushans on wildwinds.com

- Antique Indian Coins at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 7 February 2013)

- Brief Guide to Kushan History Archived 25 September 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- The CoinIndia Online Catalogue of Kushan Coins

- Dedicated resource to study of Kushan Empire Archived 25 September 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- imalayan and Central Asian Studies: Journal of Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation Volume 5 Issue 2

.svg.png.webp)