Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount

Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount[6] (previously known as Lōʻihi) is an active submarine volcano about 22 mi (35 km) off the southeast coast of the island of Hawaii.[7] The top of the seamount is about 3,200 ft (975 m) below sea level. This seamount is on the flank of Mauna Loa, the largest shield volcano on Earth. Kamaʻehuakanaloa is the newest volcano in the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain, a string of volcanoes that stretches about 3,900 mi (6,200 km) northwest of Kamaʻehuakanaloa. Unlike most active volcanoes in the Pacific Ocean that make up the active plate margins on the Pacific Ring of Fire, Kamaʻehuakanaloa and the other volcanoes of the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain are hotspot volcanoes and formed well away from the nearest plate boundary. Volcanoes in the Hawaiian Islands arise from the Hawaii hotspot, and as the youngest volcano in the chain, Kamaʻehuakanaloa is the only Hawaiian volcano in the deep submarine preshield stage of development.

| Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount | |

|---|---|

Yellow iron oxide-covered lava rock on the flank of Kamaʻehuakanaloa | |

Southeast of the island of Hawaiʻi, Hawaii, U.S. | |

| Summit depth | 3,200 ft (975 m).[1] |

| Height | over 10,000 ft (3,000 m) above the ocean floor[2] |

| Summit area | Volume – 160 cu mi (670 km3)[3] |

| Translation | "glowing child of Kanaloa"[4] (from Hawaiian) |

| Location | |

| Location | Southeast of the island of Hawaiʻi, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 18.92°N 155.27°W[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Geology | |

| Type | Submarine volcano |

| Volcanic arc/chain | Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain |

| Age of rock | At least 400,000 years old[5] |

| Last eruption | February to August 1996[3] |

| History | |

| Discovery date | 1940 – US Coast and Geodetic Survey chart number 4115[5] |

| First visit | 1978[5] |

Kamaʻehuakanaloa began forming around 400,000 years ago and is expected to begin emerging above sea level about 10,000–100,000 years from now. At its summit, Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount stands more than 10,000 ft (3,000 m) above the seafloor, making it taller than Mount St. Helens was before its catastrophic 1980 eruption. A diverse microbial community resides around Kamaʻehuakanaloa many hydrothermal vents.

In the summer of 1996, a swarm of 4,070 earthquakes was recorded at Kamaʻehuakanaloa. At the time this was the most energetic earthquake swarm in Hawaii recorded history. The swarm altered 4 to 5 sq mi (10 to 13 km2) of the seamount's summit; one section, Pele's Vents, collapsed entirely upon itself and formed the renamed Pele's Pit. The volcano has remained relatively active since the 1996 swarm and is monitored by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). The Hawaii Undersea Geological Observatory (HUGO) provided real-time data on Kamaʻehuakanaloa between 1997 and 1998. Kamaʻehuakanaloa's last known eruption was in 1996, before the earthquake swarm of that summer.

Naming

The name Kamaʻehuakanaloa is a Hawaiian language word for "glowing child of Kanaloa", the god of the ocean.[8] This name was found in two Hawaiian mele from the 19th and early twentieth centuries based on research at the Bishop Museum and was assigned by the Hawaiian Board on Geographical Names in 2021 and adopted by the U.S. Geological Survey.[8][9] From 1955 to 2021 seamount was called "Lōʻihi", the Hawaiian word for "long", describing its shape.

Characteristics

Geology

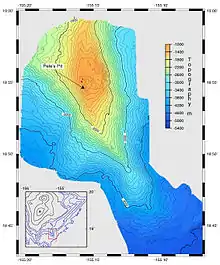

Kamaʻehuakanaloa is a seamount, or underwater volcano, on the flank of Mauna Loa, the Earth's largest shield volcano. It is the newest volcano created by the Hawaiʻi hotspot in the extensive Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain. The distance between the summit of the older Mauna Loa and the summit of Kamaʻehuakanaloa is about 50 mi (80 km), which is, coincidentally, also the approximate diameter of the Hawaiʻi hotspot.[3] Kamaʻehuakanaloa consists of a summit area with three pit craters, a 7 mi (11 km) long rift zone extending north from the summit, and a 12 mi (19 km) long rift zone extending south-southeast from the summit.[10]

The summit's pit craters are named West Pit, East Pit, and Pele's Pit.[11] Pele's Pit is the youngest of this group and is located at the southern part of the summit. The walls of Pele's Pit stand 700 ft (200 m) high and were formed in July 1996 when its predecessor, Pele's Vent, a hydrothermal field near Kamaʻehuakanaloa summit, collapsed into a large depression.[7] The thick crater walls of Pele's Pit – averaging 70 ft (20 m) in width, unusually thick for Hawaiian volcanic craters – suggest its craters have filled with lava multiple times in the past.[12]

Kamaʻehuakanaloa's north–south trending rift zones create a distinctive elongated shape, from which the volcano's earlier Hawaiian name "Lōʻihi," meaning "long", derives.[13] The north rift zone consists of a longer western portion and a shorter eastern rift zone. Observations show that both the north and south rift zones lack sediment cover, indicating recent activity. A bulge in the western part of the north rift zone contains three 200–260 ft (60–80 m) cone-shaped prominences.[12]

Until 1970, Kamaʻehuakanaloa was thought to be an inactive volcano that had been transported to its current location by sea-floor spreading. The seafloor under Hawaii is 80–100 million years old and was created at the East Pacific Rise, an oceanic spreading center where new sea floor forms from magma that erupts from the mantle. New oceanic crust moves away from the spreading center. Over a period of 80–100 million years, the sea floor under Hawaii moved from the East Pacific Rise to its present location 3,700 mi (6,000 km) west, carrying ancient seamounts with it. When scientists investigated a series of earthquakes off Hawaii in 1970, they discovered that Kamaʻehuakanaloa was an active member of the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain.

Kamaʻehuakanaloa is built on the seafloor with a slope of about five degrees. Its northern base on the flank of Mauna Loa is 2,100 yd (1,900 m) below sea level, but its southern base is a more substantial 15,600 ft (4,755 m) below the surface. Thus, the summit is 3,054 ft (931 m) above the seafloor as measured from the base of its north flank, but 12,421 ft (3,786 m) high when measured from the base of its southern flank.[3] Kamaʻehuakanaloa is following the pattern of development that is characteristic of all Hawaiian volcanoes. Geochemical evidence from Kamaʻehuakanaloa's lavas indicates that Kamaʻehuakanaloa is in transition between the preshield and shield volcano stage, providing valuable clues to the early development of Hawaiian volcanoes. In the preshield stage, Hawaiian volcanoes have steeper sides and a lower level of activity, producing an alkali basalt lava.[14][15] Continued volcanism is expected to eventually create an island at Kamaʻehuakanaloa. Kamaʻehuakanaloa experiences frequent landslides; the growth of the volcano has destabilized its slopes, and extensive areas of debris inhabit the steep southeastern face. Similar deposits from other Hawaiian volcanoes indicate that landslide debris is an important product of the early development of Hawaiian volcanoes.[5] Kamaʻehuakanaloa is predicted to rise above the surface in 10,000 to 100,000 years.[1]

Age and growth

Radiometric dating was used to determine the age of rock samples from Kamaʻehuakanaloa. The Hawaii Center for Volcanology tested samples recovered by various expeditions, notably the 1978 expedition, which provided 17 dredge samples. Most of the samples were found to be of recent origin; the oldest dated rock is around 300,000 years old. Following the 1996 event, some young breccia was also collected. Based on the samples, scientists estimate Kamaʻehuakanaloa is about 400,000 years old. The rock accumulates at an average rate of 1⁄8 in (3.5 mm) per year near the base, and 1⁄4 in (7.8 mm) near the summit. If the data model from other volcanoes such as Kīlauea holds true for Kamaʻehuakanaloa, 40% of the volcano's mass formed within the last 100,000 years. Assuming a linear growth rate, Kamaʻehuakanaloa is 250,000 years old. However, as with all hotspot volcanoes, Kamaʻehuakanaloa's level of activity has increased with time; therefore, it would take at least 400,000 years for such a volcano to reach Kamaʻehuakanaloa's mass.[5] As Hawaiian volcanoes drift northwest at a rate of about 4 in (10 cm) a year, was 25 mi (40 km) southeast of its current position at the time of its initial eruption.[16]

Activity

Kamaʻehuakanaloa is a young and fairly active volcano, although less active than nearby Kīlauea. In the past few decades, several earthquake swarms have been attributed to Kamaʻehuakanaloa, the largest of which are summarized in the table below.[17] The volcano's activity is now known to predate scientific record keeping of its activity, which commenced in 1959.[18] Most earthquake swarms at Kamaʻehuakanaloa have lasted less than two days; the two exceptions are the 1990-1991 earthquake, lasting several months, and the 1996 event, which was shorter but much more pronounced. The 1996 event was directly observed by an ocean bottom seismometer (OBS), allowing scientists to calculate the depth of the earthquakes as 4 mi (6 km) to 5 mi (8 km) below the summit, approximating to the position of Kamaʻehuakanaloa's extremely shallow magma chamber.[5] This is evidence that Kamaʻehuakanaloa's seismicity is volcanic in origin.[11]

The low-level seismic activity documented on Kamaʻehuakanaloa since 1959 has shown that between two and ten earthquakes per month are traceable to the summit.[18] Earthquake swarm data have been used to analyze how well Kamaʻehuakanaloa's rocks propagate seismic waves and to investigate the relationship between earthquakes and eruptions. This low level activity is periodically punctuated by large swarms of earthquakes, each swarm composed of up to hundreds of earthquakes. The majority of the earthquakes are not distributed close to the summit, though they follow a north–south trend. Rather, most of the earthquakes occur in the southwest portion of Kamaʻehuakanaloa.[5] The largest recorded swarms took place on Kamaʻehuakanaloa in 1971, 1972, 1975, 1991–92 and 1996. The nearest seismic station is around 20 mi (30 km) from Kamaʻehuakanaloa, on the south coast of Hawaii. Seismic events that have a magnitude under 2 are recorded often, but their location cannot be determined as precisely as it can for larger events.[19] In fact, HUGO (Hawaii Undersea Geological Observatory), positioned on Kamaʻehuakanaloa's flank, detected ten times as many earthquakes as were recorded by the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) seismic network.[5]

1996 earthquake swarm

| Year(s) | Summary |

|---|---|

1996 |

Evidence of eruption in early 1996, and large, well-recorded earthquake swarm in the summer. Started on February 25, 1996, and lasted until August 9, 1996.[19][20] |

1991 |

An Ocean Bottom Observatory (OBO) device positioned on the seamount to track a recent earthquake swarm collected evidence of deflation, possibly due to magma withdrawal.[5] |

1986 |

Possible eruption, occurred on September 20, 1986 (one day).[20] |

1984–85 |

Nine events of magnitude 3 or greater, measuring between 3.0 and 4.2, were recorded from November 11, 1984, to January 21, 1985.[19] Eruption possible, but uncertain.[20] |

1975 |

Prominent earthquake swarm from August 24, 1975, to November 1975.[20] |

1971–72 |

Possible eruption from September 17, 1971, to September 1972.[20] Eruption uncertain. |

1952 |

An earthquake swarm on Kamaʻehuakanaloa in 1952 was the event that first brought attention to the volcano, previously thought extinct.[5] |

50 BC ± 1000 |

Confirmed ancient eruption[20] |

5050 BC ± 1000 |

Confirmed ancient eruption[20] |

7050 BC ± 1000 |

Confirmed ancient eruption, most likely on the east flank[19] |

| This table indexes only possible volcanic eruptions and major events. Kamaʻehuakanaloa has also been the site of multiple earthquake swarms occurring on a nearly semi-annual basis. | |

The largest amount of activity recorded for the Kamaʻehuakanaloa seamount was a swarm of 4,070 earthquakes between July 16 and August 9, 1996.[3] This series of earthquakes was the largest recorded for any Hawaiian volcano to date in both amount and intensity. Most of the earthquakes had moment magnitudes of less than 3.0. "Several hundred" had a magnitude greater than 3.0, including more than 40 greater than 4.0 and a 5.0 tremor.[19][21]

The final two weeks of the earthquake swarm were observed by a rapid response cruise launched in August 1996. The National Science Foundation funded an expedition by University of Hawaii scientists, led by Frederick Duennebier, that began investigating the swarm and its origin in August 1996. The scientists' assessment laid the groundwork for many of the expeditions that followed.[22] Follow-up expeditions to Kamaʻehuakanaloa took place, including a series of manned-submersible dives in August and September. These were supplemented by a great deal of shore-based research.[21] Fresh rock collected during the expedition revealed that an eruption occurred before the earthquake swarm.[23]

Submersible dives in August were followed by NOAA-funded research in September and October 1996. These more detailed studies showed the southern portion of Kamaʻehuakanaloa's summit had collapsed, a result of a swarm of earthquakes and the rapid withdrawal of magma from the volcano. A crater 0.6 mi (1 km) across and 330 yd (300 m) deep formed out of the rubble. The event involved the movement of 100 million cubic meters of volcanic material. A region of 3.9 to 5.0 sq mi (10 to 13 km2) of the summit was altered and populated by bus-sized pillow lava blocks, precariously perched along the outer rim of the newly formed crater. "Pele's Vents", an area on the southern side, previously considered stable, collapsed completely into a giant pit, renamed "Pele's Pit". Strong currents make submersible diving hazardous in the region.[22]

The researchers were continually met by clouds of sulfide and sulfate. The sudden collapse of Pele's Vents caused a large discharge of hydrothermal material. The presence of certain indicator minerals in the mixture suggested temperatures exceeded 250 °C (482 °F), a record for an underwater volcano. The composition of the materials was similar to that of black smokers, the hydrothermal vent plumes located along mid-ocean ridges. Samples from mounds built by discharges from the hydrothermal plumes resembled white smokers.[24]

The studies demonstrated that the most volcanically and hydrothermally active area was along the southern rift. Dives on the less active northern rim indicated that the terrain was more stable there, and high lava columns were still standing upright.[22] A new hydrothermal vent field (Naha Vents) was located in the upper-south rift zone, at a depth of 1,449 yd (1,325 m).[5][25]

Recent activity

Kamaʻehuakanaloa has remained largely quiet since the 1996 event; no activity was recorded from 2002 to 2004. The seamount showed signs of life again in 2005 by generating an earthquake bigger than any previously recorded there. USGS-ANSS (Advanced National Seismic System) reported two earthquakes, magnitudes 5.1 and 5.4, on May 13 and July 17. Both originated from a depth of 27 mi (44 km). On April 23, a magnitude 4.3 earthquake was recorded at a depth of approximately 21 mi (33 km). Between December 7, 2005, and January 18, 2006, a swarm of around 100 earthquakes occurred, the largest measuring 4 on the Moment magnitude scale and 7 to 17 mi (12 to 28 km) deep. Another earthquake measuring 4.7 was later recorded approximately midway between Kamaʻehuakanaloa and Pāhala (on the south coast of the island of Hawaii).[17]

Exploration

Early work

| Date | Study (most on R/V Kaʻimikai-o-Kanaloa and with Pisces V) |

|---|---|

| 1940 | Kamaʻehuakanaloa's first depiction on a map was on Survey Chart 4115, compiled by the US Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1940.[5] |

| 1978 | An expedition formed to study intense seismic activity in the region at the time. Data collected was the first solid evidence of the volcano being active.[5] |

| 1979 | More extensive sampling (17 dredgehauls) from this expedition seemed to confirm the 1970 results.[5] |

| 1980 | Extensive hydrothermal fields found, yielding more evidence. First high-resolution bathymetric mapping.[5] |

| 1987 | Marking and study of several hydrothermic fields[25] |

| August 1996 | Emergency response team dives reacting to extensive activity, led by Frederick Duennebier.[26] |

| Early Sept. 1997 | Studies of hydrothermal vents (Batiza and McMurtry, Chief Scientists)[26] |

| Late August 1997 | Geological studies of recent eruptions at Kamaʻehuakanaloa (Garcia and Kadko, Chief Scientists)[26] |

| October 1997 | HUGO deployment (Frederick Duennebier, Chief Scientist)[26] |

| September–October 1998 | Series of dives by multiple science parties to visit New Pit, Summit Area and HUGO.[26] |

| January 1998 | HUGO revisit (Frederick Duennebier, Chief Scientist)[26] |

| October 2002 | HUGO recovered from sea bottom.[27] |

| October 2006 October 2007 October 2008 October 2009 |

FeMO (Fe-Oxidizing Microbial Observatory) cruises to investigate iron-oxidizing microbes at Kamaʻehuakanaloa. Much is learned about Kamaʻehuakanaloa's microbial community.[28] |

Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount's first depiction on a map was on Survey Chart 4115, a bathymetric rendering of part of Hawaiʻi compiled by the US Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1940. At the time, the seamount was non-notable, being one of many in the region. A large earthquake swarm first brought attention to it in 1952. That same year, geologist Gordon A. Macdonald hypothesized that the seamount was actually an active submarine shield volcano, similar to the two active Hawaiian volcanoes, Mauna Loa and Kīlauea. Macdonald's hypothesis placed the seamount as the newest volcano in the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain, created by the Hawaiʻi hotspot. However, because the earthquakes were oriented east–west (the direction of the volcanic fault) and there was no volcanic tremor in seismometers distant from the seamount, Macdonald attributed the earthquake to faulting rather than a volcanic eruption.[5]

Geologists suspected the seamount could be an active undersea volcano, but without evidence the idea remained speculative. The volcano was largely ignored after the 1952 event, and was often mislabeled as an "older volcanic feature" in subsequent charts.[5] Geologist Kenneth O. Emery is credited with naming the seamount in 1955, describing the long and narrow shape of the volcano as Kamaʻehuakanaloa.[10][13] In 1978, an expedition studied intense, repeated seismic activity known as earthquake swarms in and around the Kamaʻehuakanaloa area. Rather than finding an old, extinct seamount, data collected revealed Kamaʻehuakanaloa to be a young, possibly active volcano. Observations showed the volcano to be encrusted with young and old lava flows. Fluids erupting from active hydrothermal vents were also found.[2]

In 1978, a US Geological Survey research ship collected dredge samples and photographed Kamaʻehuakanaloa's summit with the goal of studying whether Kamaʻehuakanaloa is active. Analysis of the photos and testing of pillow lava rock samples appeared to show that the material was "fresh", yielding more evidence that Kamaʻehuakanaloa is still active. An expedition from October 1980 to January 1981 collected further dredge samples and photographs, providing additional confirmation.[29] Studies indicated that the eruptions came from the southern part of the rift crater. This area is closest to the Hawaiʻi hotspot, which supplies Kamaʻehuakanaloa with magma.[5] Following a 1986 seismic event, a network of five ocean bottom observatories (OBOs) were deployed on Kamaʻehuakanaloa for a month. Kamaʻehuakanaloa's frequent seismicity makes it an ideal candidate for seismic study through OBOs.[5] In 1987, the submersible DSV Alvin was used to survey Kamaʻehuakanaloa[30] Another autonomous observatory was positioned on Kamaʻehuakanaloa in 1991 to track earthquake swarms.[5]

1996 to present

The bulk of information about Kamaʻehuakanaloa comes from dives made in response to the 1996 eruption. In a dive conducted almost immediately after seismic activity was reported, visibility was greatly reduced by high concentrations of displaced minerals and large floating mats of bacteria in the water. The bacteria that feed on the dissolved nutrients had already begun colonizing the new hydrothermal vents at Pele's Pit (formed from the collapse of the old ones), and may be indicators of the kinds of material ejected from the newly formed vents. They were carefully sampled for further analysis in a laboratory.[22] An OBO briefly sat on the summit before a more permanent probe could be installed.[31]

Repeated multibeam bathymetric mapping was used to measure the changes in the summit following the 1996 collapse. Hydrothermal plume surveys confirmed changes in the energy, and dissolved minerals emanating from Kamaʻehuakanaloa. Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory, HURL's 2,000 m (6,562 ft) submersible Pisces V allowed scientists to sample the vent waters, microorganisms and hydrothermal mineral deposits.[7]

Since 2006, the Fe-Oxidizing Microbial Observatory (FeMO), funded by the National Science Foundation and Microbial Observatory Program, has led cruises to Kamaʻehuakanaloa investigate its microbiology every October. The first cruise, on the ship R/V Melville and exploiting the submersible JASON2, lasted from September 22 to October 9. These cruises study the large number of Fe-oxidizing bacteria that have colonized Kamaʻehuakanaloa. Kamaʻehuakanaloa's extensive vent system is characterized by a high concentration of CO2 and iron, while being low in sulfide. These characteristics make a perfect environment for iron-oxidizing bacteria, called FeOB, to thrive in.[28]

HUGO (Hawaii Undersea Geological Observatory)

In 1997, scientists from the University of Hawaiʻi installed an ocean bottom observatory on the summit of Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount.[17] The submarine observatory was nicknamed HUGO, (Hawaiʻi Undersea Geological Observatory). HUGO was connected to the shore, 34 km (21 mi) away, by a fiber optic cable. It was designed to give scientists real-time seismic, chemical and visual data about the state of Kamaʻehuakanaloa, which had by then become an international laboratory for the study of undersea volcanism.[22] The cable that provided HUGO with power and communications broke in April 1998, effectively shutting it down. The observatory was recovered from the seafloor in 2002.[32]

Ecology

Hydrothermal vent geochemistry

| Vent[25] | Depth | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pele's | 1,000 m (3,281 ft) | Summit | Destroyed 1996 |

| Kapo's | 1,280 m (4,199 ft) | Upper South rift | No longer venting |

| Forbidden | 1,160 m (3,806 ft) | Pele's Pit | over 200 °C (392 °F) |

| Lohiau ("slow") | 1,173 m (3,850 ft)[11] | Pele's Pit | 77 °C (171 °F) |

| Pahaku ("rocky") | 1,196 m (3,924 ft) | South rift zone | 17 °C (63 °F) |

| Ula ("red") | 1,099 m (3,606 ft) | South summit | Diffuse venting |

| Maximilian | 1,249 m (4,098 ft) | West summit flank | Diffuse venting |

| Naha | 1,325 m (4,347 ft) | South rift | 23 °C (73 °F) |

Kamaʻehuakanaloa's mid-Pacific location and its well-sustained hydrothermal system contribute to a rich oasis for a microbial ecosystem. Areas of extensive hydrothermal venting are found on Kamaʻehuakanaloa's crater floor and north slope,[7] and along the summit of Kamaʻehuakanaloa itself. Active hydrothermal vents were first discovered at Kamaʻehuakanaloa in the late 1980s. These vents are remarkably similar to those found at the mid-ocean ridges, with similar composition and thermal differences. The two most prominent vent fields are at the summit: Pele's Pit (formally Pele's Vents) and Kapo's Vents. They are named after the Hawaiian deity Pele and her sister Kapo. These vents were considered "low temperature vents" because their waters were only about 30 °C (86 °F). The volcanic eruption of 1996 and the creation of Pele's Pit changed this, and initiated high temperature venting; exit temperatures were measured at 77 °C (171 °F) in 1996.[25]

Microorganisms

The vents lie 1,100 to 1,325 m (3,609 to 4,347 ft) below the surface, and range in temperature from 10 to over 200 °C (392 °F).[25][33] The vent fluids are characterized by a high concentration of CO

2 (up to 17 mM) and Fe (Iron), but low in sulfide. Low oxygen and pH levels are important factors in supporting the high amounts of Fe (iron), one of the hallmark features of Kamaʻehuakanaloa. These characteristics make a perfect environment for iron-oxidizing bacteria, called FeOB, to thrive in.[28] An example of these species is Mariprofundus ferrooxydans, sole member of the class Zetaproteobacteria.[34] The composition of the materials was similar to that of black smokers, that are a habitat of archaea extremophiles. Dissolution and oxidation of the mineral observed over the next two years suggests the sulfate is not easily preserved.[24]

A diverse community of microbial mats surround the vents and virtually cover Pele's Pit. The Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory (HURL), NOAA's Research Center for Hawaiʻi and the Western Pacific, monitors and researches the hydrothermal systems and studies the local community.[7] The National Science Foundation (NSF) funded an extremophile sampling expedition to Kamaʻehuakanaloa in 1999. Microbial mats surrounded the 160 °C (320 °F) vents, and included a novel jelly-like organism. Samples were collected for study at NSF's Marine Bioproducts Engineering Center (MarBEC).[7] In 2001, Pisces V collected samples of the organisms and brought them to the surface for study.[22]

NOAA's National Undersea Research Center and NSF's Marine Bioproducts Engineering Center are cooperating to sample and research the local bacteria and archaea extremophiles.[7] The fourth FeMO (Fe-Oxidizing Microbial Observatory) cruise occurred during October 2009.[35]

Macroorganisms

Marine life inhabiting the waters around Kamaʻehuakanaloa is not as diverse as life at other, less active seamounts. Fish found living near Kamaʻehuakanaloa include the Celebes monkfish (Sladenia remiger), and members of the Cutthroat eel family, Synaphobranchidae.[36] Invertebrates identified in the area include two species endemic to the hydrothermal vents, a bresiliid shrimp (Opaepele loihi) of the family Alvinocarididae (described in 1995), and a tube or pogonophoran worm. Dives conducted after the 1996 earthquake swarms were unable to find either the shrimp or the worm, and it is not known if there are lasting effects on these species.[37]

From 1982 to 1992, researchers in Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory submersibles photographed the fish of Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount, Johnston Atoll, and Cross Seamount at depths between 40 and 2,000 m (130 and 6,560 ft).[38][39] A small number of species identified at Kamaʻehuakanaloa were newly recorded sightings in Hawaiʻi, including the Tassled coffinfish (Chaunax fimbriatus), and the Celebes monkfish.[38]

References

- "Lōʻihi". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- Rubin, Ken (2006-01-19). "General Information About Loihi". Hawaii Center for Volcanology. SOEST. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- "Lōʻihi Seamount Hawaiʻi's Youngest Submarine Volcano". Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- Bobby Camara (October 1, 2021). "A Change of Name". Ka Wai Ola. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- Michael O. Garcia, Jackie Caplan-Auerbach, Eric H. De Carlo, M.D. Kurz, N. Becker (2005). "Geochemistry, and Earthquake History of Lōʻihi Seamount, Hawaiʻi's youngest volcano" (PDF). Chemie der Erde – Geochemistry. 66 (2): 81–108. Bibcode:2006ChEG...66...81G. doi:10.1016/j.chemer.2005.09.002. hdl:1912/1102. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - "Kama'ehuakanaloa | U.S. Geological Survey". www.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- Malahoff, Alexander (2000-12-18). "Loihi Submarine Volcano: A unique, natural extremophile laboratory". Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (NOAA). Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- Camara, Bobby (2021-10-01). "A Change of Name". Ka Wai Ola. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- "Kama'ehuakanaloa". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- Malahoff, Alexander (1987). "Geology of the summit of Loihi submarine volcano". In Decker, Robert W.; Wright, Thomas L.; Stauffer, Peter H (eds.). Volcanism in Hawaii: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1350. United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 1350. Vol. 1. Washington: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 133–44. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- Malahoff, Alexander; Kolotyrkina, Irina Ya.; Midson, Brian P.; Massoth, Gary J. (2006-01-06). "A decade of exploring a submarine intraplate volcano: Hydrothermal manganese and iron at Lōʻihi volcano, Hawai'i" (PDF). Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 7 (6): Q06002. Bibcode:2006GGG.....706002M. doi:10.1029/2005GC001222. ISSN 1525-2027. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- Fornari, D.J., Garcia, M.O., Tyce, R.C., Gallo, D.G. (1988). "Morphology and structure of Loihi seamount based on seabeam sonar mapping". Journal of Geophysical Research. 93 (15): 227–38. Bibcode:1988JGR....9315227F. doi:10.1029/jb093ib12p15227. Archived from the original on 2009-04-16. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Lōʻihi, meaning "length, height, distance; long". See: Pukui, Mary Kawena; Samuel Hoyt Elbert (1986). Hawaiian dictionary: Hawaiian-English, English-Hawaiian. University of Hawaiʻi Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-8248-0703-0.

- Best, Myron G. (1991). Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. Wiley, John & Sons, Incorporated. p. 359. ISBN 978-1-4051-0588-0.

- "Evolution of Hawaiian Volcanoes". Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. USGS. September 8, 1995. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- Garcia, M.O., Grooms, D., Naughton, J. (1987). "Petrology and geochronology of volcanic rocks". Lithosphere. The Geological Society of America (20): 323–36.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Rubin, Ken (2006-01-20). "Recent Activity at Loihi Volcano – Updates on Geologic Activity at Loihi". Hawaii Center For Volcanology. SOEST. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- Caplan-Auerbach, Jackie (1998-07-22). "Recent Seismicity at Loihi Volcano". Hawaii Center for Volcanology. SOEST. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- "Loihi – Monthly Reports". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- "Loihi – Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2009-03-13. Dates for older eruptions retrieved through Isotope dating.

- Rubin, Ken (1998-07-22). "The 1996 Eruption and July–August Seismic Event". Hawaii Center for Volcanology. SOEST. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- "HURL Current Research: Loihi after the July–August event". 1999 Research. SOEST. 2001. Archived from the original on 2009-03-05. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- Garcia, M.O., Graham, D.W., Muenow, D.W., Spencer, K., Rubin, K.H., Norman, M.D. (1998). "Petrology and geochronology of basalt breccia from the 1996 earthquake swarm of Loihi seamount, Hawaii: magmatic history of its 1996 eruption". Bulletin of Volcanology. 59 (8): 577–92. Bibcode:1998BVol...59..577G. doi:10.1007/s004450050211. ISSN 0258-8900. S2CID 35103405. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Davis, Alicé S.; David A. Clague; Robert A. Zierenberg; C. Geoffrey Wheat; Brian L. Cousens (Apr 2003). "Sulfide formation related to changes in the hydrothermal system on Loihi Seamount, Hawaiʻi, following the seismic event in 1996". The Canadian Mineralogist. 41 (2): 457–472. doi:10.2113/gscanmin.41.2.457.

- Rubin, Ken (1998-07-22). "Recent Activity at Loihi Volcano: Hydrothermal Vent and Buoyant Plume Studies". Hawaii Center for Volcanology. SOEST. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- Rubin, Ken. "Cruises to Loihi Since the 1996 Eruption and Seismic Swarm". Hawaii Center for Volcanology. SOEST. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- Duennebier, Fred (2002-10-01). "HUGO: Update and Current Status". SOEST. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- "Introduction to the Biology and Geology of Loihi Seamount". Loihi Seamount. Fe-Oxidizing Microbial Observatory (FeMO). 2009-02-01. Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- Macdonald, Gordon A.; Agatin T. Abbott; Frank L. Peterson (1983) [1970]. Volcanoes in the Sea: The Geology of Hawaii (2nd ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0832-7.

- Garcia, M.O., Irving, A.J., Jorgenson, B.A., Mahoney, J.J., Ito, E. (1993). "An evaluation of temporal geochemical evolution of Loihi summit lavas: results from Alvin submersible dives". Journal of Geophysical Research. 98 (B1): 537–50. Bibcode:1993JGR....98..537G. doi:10.1029/92JB01707. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Bryan, Carol; Cooper, P. (December 1995). "Ocean-bottom seismometer observations of seismic activity at Loihi". Marine Geophysical Researches. 17 (6): 485–501. Bibcode:1995MarGR..17..485B. doi:10.1007/BF01204340. ISSN 0025-3235. S2CID 128569263. Archived from the original on 2013-01-03. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- "HUGO: The Hawaiʻi Undersea Geo-Observatory". SOEST. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- Emerson, David; Craig L. Moyer (June 2002). "Neutrophilic Fe-Oxidizing Bacteria Are Abundant at the Loihi Seamount Hydrothermal Vents and Play a Major Role in Fe Oxide Deposition". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 68 (6): 3085–93. Bibcode:2002ApEnM..68.3085E. doi:10.1128/AEM.68.6.3085-3093.2002. PMC 123976. PMID 12039770.

- Emerson, David; Rentz, Jeremy A.; Lilburn, Timothy G.; Davis, Richard E.; Aldrich, Henry; Chan, Clara; Moyer, Craig L. (2007). Reysenbach, Anna-Louise (ed.). "A novel lineage of proteobacteria involved in formation of marine Fe-oxidizing microbial mat communities". PLOS ONE. 2 (8): e667. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..667E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000667. PMC 1930151. PMID 17668050.

- "FeMO4 Dive Cruise 2009". FeMO. EarthRef.org. 2009-10-17. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- Rubin, Ken (1998-09-07). "A Tour of Loihi". Hawaii Center for Volcanology. SOEST. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- Rubin, Ken (1998-07-22). "Recent Activity at Loihi Volcano – 1996 Seismic/Volcanic Event Summary". Hawaii Center For Volcanology. SOEST. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

The only two vent-specific macrofaunal species described from Loihi have been a novel bresiliid shrimp, Opaepele loihi (Williams and Dobbs, 1995), and a unique lineage of pogonophoran worm (R. Vrijenhoek, pers. comm.). The post-event dives, however, found no evidence for either, and the long-term impact of the event on these species is unknown.

- Chave, E.H.; B.C. Mundy (1994). "Deep-Sea Benthic Fish of the Hawaiian Archipelago, Cross Seamount, and Johnston Atoll". Pacific Science. University of Hawaiʻi. 48 (4): 367–409. hdl:10125/2295.

- Data from Chave, E.H. and B.C. Mundy (1994) and Scripps Institution of Oceanography (2002). "Observation Data". University of the Pacific. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

Further reading

- Auerbach-Caplan, J.; F. Duennebier (2001-05-25). "Seismic and acoustic signals detected at Loʻihi Seamount by the Hawaiʻi Undersea Geo-Observatory" (PDF). Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2 (5): 1525–2027. Bibcode:2001GGG.....2.1024C. doi:10.1029/2000GC000113. ISSN 1525-2027. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- Chave, E. H.; Alexander Malahoff (1998). In Deeper Waters: Photographic Studies of Hawaiian Deep-sea Habitats and Life-forms. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2003-9.

- F. K. Duennebier, N. C. Becker, J. Caplan-Auerbach, D. A. Clague, J. Cowen, M. Cremer, M. Garcia, F. Goff, A. Malahoff, G. M. McMurtry, B. P. Midson, C. L. Moyer, M. Norman, P. Okubo, J. A. Resing, J. M. Rhodes, K. Rubin, F. J. Sansone, J. R. Smith, K. Spencer, X. Wen, and C. G. Wheat (1997-06-03). "Researchers rapidly respond to submarine activity at Loihi volcano, Hawaii" (PDF). Eos, Transactions, American Geophysical Union. 78 (22): 229–33. Bibcode:1997EOSTr..78Q.229T. doi:10.1029/97EO00150.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Emery, K.O. (1955). "Submarine topography south of Hawaii". Pacific Science. University of Hawaiʻi Press. 9: 286–91.

- "Loihi – Data Sources". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- Klein, F. (1982). "Earthquakes at Lōʻihi submarine volcano and the Hawaiian hot spot". Journal of Geophysical Research. 87 (A1): B9. Bibcode:1982JGR....87....9K. doi:10.1029/JA087iA01p00009. ISSN 0148-0227.

- Macdonald, G.A. (1952). "The South Hawaii Earthquakes of March and April, 1952". The Volcano Letter (515): 3–5.

- Malahoff, Alexander; Gary M. McMurtry; John C. Wiltshire; Hsueh-Wen Yeh (1982-07-15). "Geology and chemistry of hydrothermal deposits from active submarine volcano Loihi, Hawaii". Nature. 298 (5871): 234–39. Bibcode:1982Natur.298..234M. doi:10.1038/298234a0. S2CID 4268636.

- Malahoff, A.; Gregory, T.; Bossuyt, A.; Donachie, S.; Alarn, M. (Oct 2002). "A seamless system for the collection and cultivation of extremophiles from deep-ocean hydrothermal vents". IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering. 27 (4): 862–69. Bibcode:2002IJOE...27..862M. doi:10.1109/JOE.2002.804058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - J.G. Moore, D.A. Clague, W.R. Normark (Feb 1982). "Diverse basalt types from Loihi Seamount, Hawaii". Geology. 10 (2): 88–92. Bibcode:1982Geo....10...88M. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1982)10<88:DBTFLS>2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Scripps Institution of Oceanography. (2002). Benthic Invertebrate Collection Database.

External links

- Hawaii Center for Volcanology, University of Hawaiʻi.

- Kamaʻehuakanaloa Seamount – USGS website.

- Loihi Submarine Volcano: A unique, natural extremophile laboratory – NOAA research site.

- HURL Current Research – Loihi after the July–August event, on the 1996 Lōʻihi Seamount Exploration

- Recent volcanic activity at Loihi – University of Hawaiʻi

- Fe-Oxidizing Microbial Observatory Project (FeMO) Webpage – Earthref.org