Hawaiian language

Hawaiian (ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi, pronounced [ʔoːˈlɛlo həˈvɐjʔi])[2] is a Polynesian language of the Austronesian language family that takes its name from Hawaiʻi, the largest island in the tropical North Pacific archipelago where it developed. Hawaiian, along with English, is an official language of the US state of Hawaii.[3] King Kamehameha III established the first Hawaiian-language constitution in 1839 and 1840.

| Hawaiian | |

|---|---|

| ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi | |

| Native to | Hawaiian Islands |

| Region | Hawaiʻi and Niʻihau[1] |

| Ethnicity | Native Hawaiians |

Native speakers | ~24,000 (2008) |

Early forms | Proto-Austronesian

|

| Dialects |

|

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | haw |

| ISO 639-3 | haw |

| Glottolog | hawa1245 |

| ELP | Hawaiian |

| Linguasphere | 39-CAQ-e |

Hawaiian is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

For various reasons, including territorial legislation establishing English as the official language in schools, the number of native speakers of Hawaiian gradually decreased during the period from the 1830s to the 1950s. Hawaiian was essentially displaced by English on six of seven inhabited islands. In 2001, native speakers of Hawaiian amounted to less than 0.1% of the statewide population. Linguists were unsure if Hawaiian and other endangered languages would survive.[4][5]

Nevertheless, from around 1949 to the present day, there has been a gradual increase in attention to and promotion of the language. Public Hawaiian-language immersion preschools called Pūnana Leo were established in 1984; other immersion schools followed soon after that. The first students to start in immersion preschool have now graduated from college and many are fluent Hawaiian speakers. However, the language is still classified as critically endangered by UNESCO.[6]

A creole language, Hawaiian Pidgin (or Hawaii Creole English, HCE), is more commonly spoken in Hawaiʻi than Hawaiian.[7] Some linguists, as well as many locals, argue that Hawaiian Pidgin is a dialect of American English.[8] Born from the increase of immigrants from Japan, China, Puerto Rico, Korea, Portugal, Spain and the Philippines, the pidgin creole language was a necessity in the plantations. Hawaiian and immigrant laborers as well as the white luna, or overseers, found a way to communicate amongst themselves. Pidgin eventually made its way off the plantation and into the greater community, where it is still used to this day.[9]

The Hawaiian alphabet has 13 letters: five vowels: a e i o u (each with a long pronunciation and a short one) and eight consonants: he ke la mu nu pi we ʻokina (a glottal stop).

Name

The Hawaiian language takes its name from the largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago, Hawaii (Hawaiʻi in the Hawaiian language). The island name was first written in English in 1778 by British explorer James Cook and his crew members. They wrote it as "Owhyhee" or "Owhyee". It is written "Oh-Why-hee" on the first map of Sandwich Islands engraved by Tobias Conrad Lotter in 1781.[10] Explorers Mortimer (1791) and Otto von Kotzebue (1821) used that spelling.[11]

The initial "O" in the name "Oh-Why-hee" is a reflection of the fact that Hawaiian predicates unique identity by using a copula form, o, immediately before a proper noun.[12] Thus, in Hawaiian, the name of the island is expressed by saying O Hawaiʻi, which means "[This] is Hawaiʻi."[13] The Cook expedition also wrote "Otaheite" rather than "Tahiti."[14]

The spelling "why" in the name reflects the [ʍ] pronunciation of wh in 18th-century English (still used in parts of the English-speaking world). Why was pronounced [ʍai]. The spelling "hee" or "ee" in the name represents the sounds [hi], or [i].[15]

Putting the parts together, O-why-(h)ee reflects [o-hwai-i], a reasonable approximation of the native pronunciation, [o hɐwɐiʔi].

American missionaries bound for Hawaiʻi used the phrases "Owhihe Language" and "Owhyhee language" in Boston prior to their departure in October 1819 and during their five-month voyage to Hawaiʻi.[16] They still used such phrases as late as March 1822.[17] However, by July 1823, they had begun using the phrase "Hawaiian Language."[18]

In Hawaiian, the language is called ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi, since adjectives follow nouns.[19]

Family and origin

Hawaiian is a Polynesian member of the Austronesian language family.[20] It is closely related to other Polynesian languages, such as Samoan, Marquesan, Tahitian, Māori, Rapa Nui (the language of Easter Island) and Tongan.[21]

According to Schütz (1994), the Marquesans colonized the archipelago in roughly 300 CE[22] followed by later waves of immigration from the Society Islands and Samoa-Tonga. Their languages, over time, became the Hawaiian language within the Hawaiian Islands.[23] Kimura and Wilson (1983) also state:

Linguists agree that Hawaiian is closely related to Eastern Polynesian, with a particularly strong link in the Southern Marquesas, and a secondary link in Tahiti, which may be explained by voyaging between the Hawaiian and Society Islands.[24]

Mutual intelligibility

Jack H. Ward (1962) conducted a study using basic words and short utterances to determine the level of comprehension between different Polynesian languages. The mutual intelligibility of Hawaiian was found to be 41.2% with Marquesan, 37.5% with Tahitian, 25.5% with Samoan and 6.4% with Tongan.[25]

History

First European contact

In 1778, British explorer James Cook made Europe's initial, recorded first contact with Hawaiʻi, beginning a new phase in the development of Hawaiian. During the next forty years, the sounds of Spanish (1789), Russian (1804), French (1816), and German (1816) arrived in Hawaiʻi via other explorers and businessmen. Hawaiian began to be written for the first time, largely restricted to isolated names and words, and word lists collected by explorers and travelers.[26]

The early explorers and merchants who first brought European languages to the Hawaiian islands also took on a few native crew members who brought the Hawaiian language into new territory.[27] Hawaiians took these nautical jobs because their traditional way of life changed due to plantations, and although there were not enough of these Hawaiian-speaking explorers to establish any viable speech communities abroad, they still had a noticeable presence.[28] One of them, a boy in his teens known as Obookiah (ʻŌpūkahaʻia), had a major impact on the future of the language. He sailed to New England, where he eventually became a student at the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Connecticut. He inspired New Englanders to support a Christian mission to Hawaiʻi, and provided information on the Hawaiian language to the American missionaries there prior to their departure for Hawaiʻi in 1819.[29] Adelbert von Chamisso too might have consulted with a native speaker of Hawaiian in Berlin, Germany, before publishing his grammar of Hawaiian (Über die Hawaiische Sprache) in 1837.[30]

Folk tales

Like all natural spoken languages, the Hawaiian language was originally an oral language. The native people of the Hawaiian language relayed religion, traditions, history, and views of their world through stories that were handed down from generation to generation. One form of storytelling most commonly associated with the Hawaiian islands is hula. Nathaniel B. Emerson notes that "It kept the communal imagination in living touch with the nation's legendary past".[31]

The islanders' connection with their stories is argued to be one reason why Captain James Cook received a pleasant welcome. Marshall Sahlins has observed that Hawaiian folktales began bearing similar content to those of the Western world in the eighteenth century.[32] He argues this was caused by the timing of Captain Cook's arrival, which was coincidentally when the indigenous Hawaiians were celebrating the Makahiki festival, which is the annual celebration of the harvest in honor of the god Lono. The celebration lasts for the entirety of the rainy season. It is a time of peace with much emphasis on amusements, food, games, and dancing.[33] The islanders' story foretold of the god Lono's return at the time of the Makahiki festival.[34] The arrival of Captain Cook on the Endeavor with its massive white sails, unlike anything any Hawaiians had ever seen, seemed like the god Lono arriving on his floating island with white flags as it had been foretold.[9]

Written Hawaiian

In 1820, Protestant missionaries from New England arrived in Hawaiʻi, and in a few years converted the chiefs to Congregational Protestantism, who in turn converted their subjects. To the missionaries, the thorough Christianization of the kingdom necessitated a complete translation of the Bible to Hawaiian, a previously unwritten language, and therefore the creation of a standard spelling that should be as easy to master as possible. The orthography created by the missionaries was so straightforward that literacy spread very quickly among the adult population; at the same time, the Mission set more and more schools for children.

In 1834, the first Hawaiian-language newspapers were published by missionaries working with locals. The missionaries also played a significant role in publishing a vocabulary (1836)[35] grammar (1854)[36] and dictionary (1865)[37] of Hawaiian. The Hawaiian Bible was fully completed in 1839; by then, the Mission had such a wide-reaching school network that, when in 1840 it handed it over to the Hawaiian government, the Hawaiian Legislature mandated compulsory state-funded education for all children under 14 years of age, including girls, twelve years before any similar compulsory education law was enacted for the first time in any of the United States.[38]

Literacy in Hawaiian was so widespread that in 1842 a law mandated that people born after 1819 had to be literate to be allowed to marry. In his Report to the Legislature for the year 1853 Richard Armstrong, the minister of Public Instruction, bragged that 75% of the adult population could read. [39] Use of the language among the general population might have peaked around 1881. Even so, some people worried, as early as 1854, that the language was "soon destined to extinction."[40]

When Hawaiian King David Kalākaua took a trip around the world, he brought his native language with him. When his wife, Queen Kapiʻolani, and his sister, Princess (later Queen) Liliʻuokalani, took a trip across North America and on to the British Islands, in 1887, Liliʻuokalani's composition Aloha ʻOe was already a famous song in the U.S.[41]

Suppression of Hawaiian

The decline of the Hawaiian language was accelerated by the coup that overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy and dethroned the existing Hawaiian queen. Thereafter, a law was instituted that required English as the main language of school instruction.[42] The law cited is identified as Act 57, sec. 30 of the 1896 Laws of the Republic of Hawaiʻi:

The English Language shall be the medium and basis of instruction in all public and private schools, provided that where it is desired that another language shall be taught in addition to the English language, such instruction may be authorized by the Department, either by its rules, the curriculum of the school, or by direct order in any particular instance. Any schools that shall not conform to the provisions of this section shall not be recognized by the Department.

— The Laws of Hawaii, Chapter 10, Section 123[43]

This law established English as the medium of instruction for the government-recognized schools both "public and private". While it did not ban or make illegal the Hawaiian language in other contexts, its implementation in the schools had far-reaching effects. Those who had been pushing for English-only schools took this law as licence to extinguish the native language at the early education level. While the law did not make Hawaiian illegal (it was still commonly spoken at the time), many children who spoke Hawaiian at school, including on the playground, were disciplined. This included corporal punishment and going to the home of the offending child to advise them strongly to stop speaking it in their home.[44] Moreover, the law specifically provided for teaching languages "in addition to the English language," reducing Hawaiian to the status of an extra language, subject to approval by the department. Hawaiian was not taught initially in any school, including the all-Hawaiian Kamehameha Schools. This is largely because when these schools were founded, like Kamehameha Schools founded in 1887 (nine years before this law), Hawaiian was being spoken in the home. Once this law was enacted, individuals at these institutions took it upon themselves to enforce a ban on Hawaiian. Beginning in 1900, Mary Kawena Pukui, who was later the co-author of the Hawaiian–English Dictionary, was punished for speaking Hawaiian by being rapped on the forehead, allowed to eat only bread and water for lunch, and denied home visits on holidays.[45] Winona Beamer was expelled from Kamehameha Schools in 1937 for chanting Hawaiian.[46] Due in part to this systemic suppression of the language after the overthrow, Hawaiian is still considered a critically endangered language.

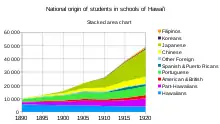

However, informal coercion to drop Hawaiian would not have worked by itself. Just as important was the fact that, in the same period, native Hawaiians were becoming a minority in their own land on account of the growing influx of foreign labourers and their children. Whereas in 1890 pure Hawaiian students made 56% of school enrollment, in 1900 their numbers were down to 32% and, in 1910, to 16.9%. [47] At the same time, Hawaiians were very prone to intermarriage: the number of "Part-Hawaiian" students (i.e., children of mixed White-Hawaiian marriages) grew from 1573 in 1890 to 3718 in 1910. [47] In such mixed households, the low prestige of Hawaiian lead to the adoption of English as the family language. Moreover, Hawaiians lived mostly in the cities or scattered across the countryside, in direct contact with other ethnic groups and without any stronghold (with the exception of Niʻihau). Thus, even pure Hawaiian children would converse daily with their schoolmates of diverse mother tongues in English, which was now not just the teachers' language but also the common language needed for everyday communication among friends and neighbours out of school as well. In only a generation English (or rather Pidgin) would become the primary and dominant language of all children, despite the efforts of Hawaiian and immigrant parents to maintain their ancestral languages within the family.

1949 to present

In 1949, the legislature of the Territory of Hawaiʻi commissioned Mary Pukui and Samuel Elbert to write a new dictionary of Hawaiian, either revising the Andrews-Parker work or starting from scratch.[48] Pukui and Elbert took a middle course, using what they could from the Andrews dictionary, but making certain improvements and additions that were more significant than a minor revision. The dictionary they produced, in 1957, introduced an era of gradual increase in attention to the language and culture.

Language revitalization and Hawaiian culture has seen a major revival since the Hawaiian renaissance in the 1970s.[49] Forming in 1983, the ʻAha Pūnana Leo, meaning "language nest" in Hawaiian, opened its first center in 1984. It was a privately funded Hawaiian preschool program that invited native Hawaiian elders to speak to children in Hawaiian every day.[50] Efforts to promote the language have increased in recent decades. Hawaiian-language "immersion" schools are now open to children whose families want to reintroduce Hawaiian language for future generations.[51] The ʻAha Pūnana Leo's Hawaiian language preschools in Hilo, Hawaii, have received international recognition.[52] The local National Public Radio station features a short segment titled "Hawaiian word of the day" and a Hawaiian language news broadcast. Honolulu television station KGMB ran a weekly Hawaiian language program, ʻĀhaʻi ʻŌlelo Ola, as recently as 2010.[53] Additionally, the Sunday editions of the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, the largest newspaper in Hawaii, feature a brief article called Kauakukalahale written entirely in Hawaiian by teachers, students, and community members.[54]

Today, the number of native speakers of Hawaiian, which was under 0.1% of the statewide population in 1997, has risen to 2,000, out of 24,000 total who are fluent in the language, according to the US 2011 census. On six of the seven permanently inhabited islands, Hawaiian has been largely displaced by English, but on Niʻihau, native speakers of Hawaiian have remained fairly isolated and have continued to use Hawaiian almost exclusively.[55][42][56]

Niʻihau

Niʻihau is the only area in the world where Hawaiian is the first language and English is a foreign language.[57]

— Samuel Elbert and Mary Pukui, Hawaiian Grammar (1979)

The isolated island of Niʻihau, located off the southwest coast of Kauai, is the one island where Hawaiian (more specifically a local dialect of Hawaiian known as Niihau dialect) is still spoken as the language of daily life.[55] Elbert & Pukui (1979:23) states that "[v]ariations in Hawaiian dialects have not been systematically studied", and that "[t]he dialect of Niʻihau is the most aberrant and the one most in need of study". They recognized that Niʻihauans can speak Hawaiian in substantially different ways. Their statements are based in part on some specific observations made by Newbrand (1951). (See Hawaiian phonological processes)

Friction has developed between those on Niʻihau that speak Hawaiian as a first language, and those who speak Hawaiian as a second language, especially those educated by the College of Hawaiian Language at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo. The university sponsors a Hawaiian Language Lexicon Committee (Kōmike Huaʻōlelo Hou) which coins words for concepts that historically have not existed in the language, like "computer" and "cell phone". These words are generally not incorporated into the Niʻihau dialect, which often coins its own words organically. Some new words are Hawaiianized versions of English words, and some are composed of Hawaiian roots and unrelated to English sounds.[58]

Hawaiian in schools

Hawaiian medium schools

The Hawaiian medium education system is a combination of charter, public, and private schools. K-6 schools operate under coordinated governance of the Department of Education and the charter school, while the preK-12 laboratory system is governed by the Department of Education, the ʻAha Pūnana Leo, and the charter school. Over 80% of graduates from these laboratory schools attend college, some of which include Ivy-League schools.[59] Hawaiian is now an authorized course in the Department of Education language curriculum, though not all schools offer the language.[9]

There are two kinds of Hawaiian-immersion medium schools: k-12 total Hawaiian-immersion schools, and grades 7-12 partial Hawaiian immersion schools, the later having some classes are taught in English and others are taught in Hawaiian.[60] One of the main focuses of Hawaiian-medium schools is to teach the form and structure of the Hawaiian language by modeling sentences as a "pepeke", meaning squid in Hawaiian.[61] In this case the pepeke is a metaphor that features the body of a squid with the three essential parts: the poʻo (head), the ʻawe (tentacles) and the piko (where the poʻo and ʻawe meet) representing how a sentence is structured. The poʻo represents the predicate, the piko representing the subject and the ʻawe representing the object.[62] Hawaiian immersion schools teach content that both adheres to state standards and stresses Hawaiian culture and values. The existence of immersion schools in Hawaiʻi has developed the opportunity for intergenerational transmission of Hawaiian at home.[63]

Higher education

The Ka Haka ʻUla O Keʻelikōlani College of Hawaiian Language is a college at the University of Hawaii at Hilo dedicated to providing courses and programs entirely in Hawaiian. It educates and provides training for teachers and school administrators of Hawaiian medium schools. It is the only college in the United States of America that offers a master's and doctorate's degree in an Indigenous language. Programs offered at The Ka Haka ʻUla O Keʻelikōlani College of Hawaiian Language are known collectively as the "Hilo model" and has been imitated by the Cherokee immersion program and several other Indigenous revitalization programs.[64]

Since 1921, the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa and all of the University of Hawaiʻi Community Colleges also offer Hawaiian language courses to students for credit. The university now also offers free online courses not for credit, along with a few other websites and apps such as Duolingo.[65]

Orthography

Hawaiians had no written language prior to Western contact, except for petroglyph symbols. The modern Hawaiian alphabet, ka pīʻāpā Hawaiʻi, is based on the Latin script. Hawaiian words end only[66] in vowels, and every consonant must be followed by a vowel. The Hawaiian alphabetical order has all of the vowels before the consonants,[67] as in the following chart.

| Aa | Ee | Ii | Oo | Uu | Hh | Kk | Ll | Mm | Nn | Pp | Ww | ʻ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /a/ | /e/ | /i/ | /o/ | /u/ | /h/ | /k~t/ | /l/ | /m/ | /n/ | /p/ | /v~w/ | /ʔ/ |

Origin

This writing system was developed by American Protestant missionaries during 1820–1826.[68] It was the first thing they ever printed in Hawaiʻi, on January 7, 1822, and it originally included the consonants B, D, R, T, and V, in addition to the current ones (H, K, L, M, N, P, W), and it had F, G, S, Y and Z for "spelling foreign words". The initial printing also showed the five vowel letters (A, E, I, O, U) and seven of the short diphthongs (AE, AI, AO, AU, EI, EU, OU).[69]

In 1826, the developers voted to eliminate some of the letters which represented functionally redundant allophones (called "interchangeable letters"), enabling the Hawaiian alphabet to approach the ideal state of one-symbol-one-phoneme, and thereby optimizing the ease with which people could teach and learn the reading and writing of Hawaiian.[70] For example, instead of spelling one and the same word as pule, bule, pure, and bure (because of interchangeable p/b and l/r), the word is spelled only as pule.

- Interchangeable B/P. B was dropped, P was kept.

- Interchangeable L/R. R and D were dropped, L was kept.

- Interchangeable K/T. T was dropped, K was kept.

- Interchangeable V/W. V was dropped, W was kept.

However, hundreds of words were very rapidly borrowed into Hawaiian from English, Greek, Hebrew, Latin, and Syriac.[71][72][73] Although these loan words were necessarily Hawaiianized, they often retained some of their "non-Hawaiian letters" in their published forms. For example, Brazil fully Hawaiianized is Palakila, but retaining "foreign letters" it is Barazila.[74] Another example is Gibraltar, written as Kipalaleka or Gibaraleta.[75] While [z] and [ɡ] are not regarded as Hawaiian sounds, [b], [ɹ], and [t] were represented in the original alphabet, so the letters (b, r, and t) for the latter are not truly "non-Hawaiian" or "foreign", even though their post-1826 use in published matter generally marked words of foreign origin.

Glottal stop

ʻOkina (ʻoki 'cut' + -na '-ing') is the modern Hawaiian name for the symbol (a letter) that represents the glottal stop.[76] It was formerly known as ʻuʻina ("snap").[77][78]

For examples of the ʻokina, consider the Hawaiian words Hawaiʻi and Oʻahu (often simply Hawaii and Oahu in English orthography). In Hawaiian, these words are pronounced [hʌˈʋʌi.ʔi] and [oˈʔʌ.hu], and are written with an ʻokina where the glottal stop is pronounced.[79][80]

Elbert & Pukui's Hawaiian Grammar says "The glottal stop, ‘, is made by closing the glottis or space between the vocal cords, the result being something like the hiatus in English oh-oh."[81]

History

As early as 1823, the missionaries made some limited use of the apostrophe to represent the glottal stop,[82] but they did not make it a letter of the alphabet. In publishing the Hawaiian Bible, they used it to distinguish koʻu ('my') from kou ('your').[83] In 1864, William DeWitt Alexander published a grammar of Hawaiian in which he made it clear that the glottal stop (calling it "guttural break") is definitely a true consonant of the Hawaiian language.[84] He wrote it using an apostrophe. In 1922, the Andrews-Parker dictionary of Hawaiian made limited use of the opening single quote symbol, then called "reversed apostrophe" or "inverse comma", to represent the glottal stop.[85] Subsequent dictionaries and written material associated with the Hawaiian language revitalization have preferred to use this symbol, the ʻokina, to better represent spoken Hawaiian. Nonetheless, excluding the ʻokina may facilitate interface with English-oriented media, or even be preferred stylistically by some Hawaiian speakers, in homage to 19th century written texts. So there is variation today in the use of this symbol.

Electronic encoding

The ʻokina is written in various ways for electronic uses:

- turned comma: ʻ, Unicode hex value 02BB (decimal 699). This does not always have the correct appearance because it is not supported in some fonts.

- opening single quote, a.k.a. left single quotation mark: ‘ Unicode hex value 2018 (decimal 8216). In many fonts this character looks like either a left-leaning single quotation mark or a quotation mark thicker at the bottom than at the top. In more traditional serif fonts such as Times New Roman it can look like a very small "6" with the circle filled in black: ‘.

Because many people who want to write the ʻokina are not familiar with these specific characters and/or do not have access to the appropriate fonts and input and display systems, it is sometimes written with more familiar and readily available characters:

- the ASCII apostrophe ', Unicode hex value 27 (decimal 39),[86] following the missionary tradition.

- the ASCII grave accent (often called "backquote" or "backtick") `,[87] Unicode hex value 60 (decimal 96)

- the right single quotation mark, or "curly apostrophe" ’, Unicode hex value 2019 (decimal 8217)[88]

Macron

A modern Hawaiian name for the macron symbol is kahakō (kaha 'mark' + kō 'long').[89] It was formerly known as mekona (Hawaiianization of macron). It can be written as a diacritical mark which looks like a hyphen or dash written above a vowel, i.e., ā ē ī ō ū and Ā Ē Ī Ō Ū. It is used to show that the marked vowel is a "double", or "geminate", or "long" vowel, in phonological terms.[90] (See: Vowel length)

As early as 1821, at least one of the missionaries, Hiram Bingham, was using macrons (and breves) in making handwritten transcriptions of Hawaiian vowels.[91] The missionaries specifically requested their sponsor in Boston to send them some type (fonts) with accented vowel characters, including vowels with macrons, but the sponsor made only one response and sent the wrong font size (pica instead of small pica).[85] Thus, they could not print ā, ē, ī, ō, nor ū (at the right size), even though they wanted to.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ||

| Plosive | p | t ~ k | ʔ | |

| Fricative | h | |||

| Sonorant | w ~ v | l ~ ɾ | ||

Hawaiian is known for having very few consonant phonemes – eight: /p, k ~ t, ʔ, h, m, n, l, w ~ v/. It is notable that Hawaiian has allophonic variation of [t] with [k],[94][95][96][97] [w] with [v],[98] and (in some dialects) [l] with [n].[99] The [t]–[k] variation is quite unusual among the world's languages, and is likely a product both of the small number of consonants in Hawaiian, and the recent shift of historical *t to modern [t]–[k], after historical *k had shifted to [ʔ]. In some dialects, /ʔ/ remains as [k] in some words. These variations are largely free, though there are conditioning factors. /l/ tends to [n] especially in words with both /l/ and /n/, such as in the island name Lānaʻi ([laːˈnɐʔi]–[naːˈnɐʔi]), though this is not always the case: ʻeleʻele or ʻeneʻene "black". The [k] allophone is almost universal at the beginnings of words, whereas [t] is most common before the vowel /i/. [v] is also the norm after /i/ and /e/, whereas [w] is usual after /u/ and /o/. After /a/ and initially, however, [w] and [v] are in free variation.[100]

Vowels

Hawaiian has five short and five long vowels, plus diphthongs.

Monophthongs

| Short | Long | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | Front | Back | |

| Close | i | u | iː | uː |

| Mid | ɛ ~ e | o | eː | oː |

| Open | a ~ ɐ ~ ə | aː | ||

Hawaiian has five pure vowels. The short vowels are /u, i, o, e, a/, and the long vowels, if they are considered separate phonemes rather than simply sequences of like vowels, are /uː, iː, oː, eː, aː/. When stressed, short /e/ and /a/ have been described as becoming [ɛ] and [ɐ], while when unstressed they are [e] and [ə] . Parker Jones (2017), however, did not find a reduction of /a/ to [ə] in the phonetic analysis of a young speaker from Hilo, Hawaiʻi; so there is at least some variation in how /a/ is realised.[101] /e/ also tends to become [ɛ] next to /l/, /n/, and another [ɛ], as in Pele [pɛlɛ]. Some grammatical particles vary between short and long vowels. These include a and o "of", ma "at", na and no "for". Between a back vowel /o/ or /u/ and a following non-back vowel (/a e i/), there is an epenthetic [w], which is generally not written. Between a front vowel /e/ or /i/ and a following non-front vowel (/a o u/), there is an epenthetic [j] (a y sound), which is never written.

Diphthongs

| Ending with /u/ | Ending with /i/ | Ending with /o/ | Ending with /e/ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting with /i/ | iu | |||

| Starting with /o/ | ou | oi | ||

| Starting with /e/ | eu | ei | ||

| Starting with /a/ | au | ai | ao | ae |

The short-vowel diphthongs are /iu, ou, oi, eu, ei, au, ai, ao, ae/. In all except perhaps /iu/, these are falling diphthongs. However, they are not as tightly bound as the diphthongs of English, and may be considered vowel sequences.[101] (The second vowel in such sequences may receive the stress, but in such cases it is not counted as a diphthong.) In fast speech, /ai/ tends to [ei] and /au/ tends to [ou], conflating these diphthongs with /ei/ and /ou/.

There are only a limited number of vowels which may follow long vowels, and some authors treat these sequences as diphthongs as well: /oːu, eːi, aːu, aːi, aːo, aːe/.

| Ending with /u/ | Ending with /i/ | Ending with /o/ | Ending with /e/ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting with /o/ | oːu | |||

| Starting with /e/ | eːi | |||

| Starting with /a/ | aːu | aːi | aːo | aːe |

Phonotactics

Hawaiian syllable structure is (C)V. All CV syllables occur except for wū;[102] wu occurs only in two words borrowed from English.[103][104] As shown by Schütz,[71][92][105] Hawaiian word-stress is predictable in words of one to four syllables, but not in words of five or more syllables. Hawaiian phonological processes include palatalization and deletion of consonants, as well as raising, diphthongization, deletion, and compensatory lengthening of vowels.[95][96]

Grammar

Hawaiian is an analytic language with verb–subject–object word order. While there is no use of inflection for verbs, in Hawaiian, like other Austronesian personal pronouns, declension is found in the differentiation between a- and o-class genitive case personal pronouns in order to indicate inalienable possession in a binary possessive class system. Also like many Austronesian languages, Hawaiian pronouns employ separate words for inclusive and exclusive we (clusivity), and distinguish singular, dual, and plural. The grammatical function of verbs is marked by adjacent particles (short words) and by their relative positions, that indicate tense–aspect–mood.

Some examples of verb phrase patterns:[81]

- ua VERB – perfective

- e VERB ana – imperfective

- ke VERB nei – present progressive

- e VERB – imperative

- mai VERB – negative imperative

- i VERB – purposive

- ke VERB – infinitive

Nouns can be marked with articles:

- ka honu (the turtle)

- nā honu (the turtles)

- ka hale (the house)

- ke kanaka (the person)

ka and ke are singular definite articles. ke is used before words beginning with a-, e-, o- and k-, and with some words beginning ʻ- and p-. ka is used in all other cases. nā is the plural definite article.

To show part of a group, the word kekahi is used. To show a bigger part, mau is inserted to pluralize the subject.

Examples:

- kekahi pipi (one of the cows)

- kekahi mau pipi (some of the cows)

Semantic domains

Hawaiian has thousands of words for elements of the natural world. According to the Hawaiian Electronic Library, there are thousands of names for different types of wind, rain, parts of the sea, peaks of mountains, and sky formations, demonstrating the importance of the natural world to Hawaiian culture. For example, "Hoʻomalumalu" means "sheltering cloud" and "Hoʻoweliweli" means "threatening cloud".[110]

Varieties and debates

There is a marked difference between varieties of the Hawaiian language spoken by most native Hawaiian elders and the Hawaiian Language taught in education, sometimes regarded as "University Hawaiian" or "College Hawaiian". "University Hawaiian" is often so different from the language spoken by elders that Native Hawaiian children may feel scared or ashamed to speak Hawaiian at home, limiting the language's domains to academia.[64] Language varieties spoken by elders often includes Pidgin Hawaiian, Hawaiian Pidgin, Hawaiian-infused English, or another variety of Hawaiian that is much different from the "University Hawaiian" that was standardized and documented by colonists in the 19th century.[111]

The divide between "University Hawaiian" and varieties spoken by elders has created debate over which variety of Hawaiian should be considered "real" or "authentic", as neither "University Hawaiian" nor other varieties spoken by elders are free from foreign interference. Hawaiian cultural beliefs of divine intervention as the driving force of language formation expedites distrust in what might be seen as the mechanical nature of colonial linguistic paradigms of language and its role in the standardized variety of "University Hawaiian".[111] Hawaiian's authenticity debate could have major implications for revitalization efforts as language attitudes and trends in existing language domains are both UNESCO factors in assessing a language's level of endangerment.[112]

See also

- The list of Hawaiian words and list of words of Hawaiian origin at Wiktionary, a free dictionary and Wikipedia sibling project

- Languages of the United States

- List of English words of Hawaiian origin

- Pidgin Hawaiian (not to be confused with Hawaiian Pidgin)

References

- "Hawaiian". SIL International. 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- Mary Kawena Pukui and Samuel Hoyt Elbert (2003). "lookup of ʻōlelo". in Hawaiian Dictionary. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii Press.

- "Article XV, Section 4". Constitution of the State of Hawaiʻi. Hawaiʻi State Legislature. 1978. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- see e.g. (Hinton & Hale 2001)

- "The 1897 Petition Against the Annexation of Hawaii". National Archives and Records Administration. 15 August 2016.

- "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "Languages Spoken in Hawaii". Exclusive Hawaii Rehab. 3 December 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- Fishman, Joshua A. (1977). ""Standard" versus "Dialect" in Bilingual Education: An Old Problem in a New Context". The Modern Language Journal. 61 (7): 315–325. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1977.tb05146.x. ISSN 0026-7902.

- Haertig, E.W. (1972). Nana i Ke Kumu Vol 2. Hui Hanai.

- "Carte de l'OCÉAN PACIFIQUE au Nord de l'équateur / Charte des STILLEN WELTMEERS nördlichen des Äequators" [Chart of the PACIFIC OCEAN north of the Equator] (JPG). Princeton University Library. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

French: Carte de l'OCÉAN PACIFIQUE au Nord de l'équateur, et des côtes qui le bornent des deux cotes: d'après les dernières découvertes faites par les Espagnols, les Russes et les Anglais jusqu'en 1780.

German: Charte des STILLEN WELTMEERS nördlichen des Äequators und der Küsten, die es auf beiden Seiten einschränken: Nach den neuesten, von der Spanier, Russen und Engländer bis 1780.

English (translation): Chart of the PACIFIC OCEAN north of the Equator and the Coasts that bound it on both sides: according to the latest discoveries made by the Spaniards, Russians and English up to 1780. - Schütz (1994:44, 459)

- Carter (1996:144, 174)

- Carter (1996:187–188)

- Schütz (1994:41)

- Schütz (1994:61–65)

- Schütz (1994:304, 475)

- Schütz (1994:108–109)

- Schütz (1994:306)

- Carter (1996:3 Figure 1)

- Lyovin (1997:257–258)

- "Polynesian languages". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- Schütz (1994:334–336, 338 20n)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:35–36)

- Kimura & Wilson (1983:185)

- Schütz, Albert J. (2020). Hawaiian Language Past, Present, and Future. United States: University of Hawaii Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0824869830.

- Schütz (1994:31–40)

- Schütz (1994:43–44)

- Nettle and Romaine, Daniel and Suzanne (2000). Vanishing Voices. Oxford University Press. pp. 93–97. ISBN 978-0-19-513624-1.

- Schütz (1994:85–97)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:2)

- Emerson, Nathaniel B. (1909). Unwritten Literature of Hawaii: The Sacred Songs of the Hula. Washington Government Printing Office. pp. 7.

- Sahlins, Marshall (1985). Islands of History. University of Chicago Press.

- Handy, E.S. (1972). Native Planters in Old Hawaii: Their Life, Lore, and Environment. Bishop Museum Press.

- Kanopy (Firm). (2016). Nature Gods and Tricksters of Polynesia. San Francisco, California, USA: Ka Streaming. http://[institution].kanopystreaming.com/node/161213

- Andrews (1836)

- Elbert (1954)

- Andrews (1865)

- Fernández Asensio (2019:14-15)

- Fernández Asensio (2019:15)

- quoted in Schütz (1994:269–270)

- Carter (1996:7, 169) example 138, quoting McGuire

- "Meet the last native speakers of Hawaiian". Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- Congress, United States. (1898). Congressional Edition. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 1–PA23. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- United States. Native Hawaiians Study Commission. (1983). Native Hawaiians Study Commission : report on the culture, needs, and concerns of native Hawaiians. [U.S. Dept. of the Interior]. pp. 196/213. OCLC 10865978.

- Mary Kawena Pukui, Nana i ke Kumu, Vol. 2 p. 61–62

- M. J. Harden, Voices of Wisdom: Hawaiian Elders Speak, p. 99

- Reinecke, John E. (1988) [1969]. Language and dialect in Hawaii : a sociolinguistic history to 1935. Tsuzaki, Stanley M. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 74–76. ISBN 0-8248-1209-3. OCLC 17917779.

- Schütz (1994:230)

- Snyder-Frey, Alicia (2013-05-01). "He kuleana kō kākou: Hawaiian-language learners and the construction of (alter)native identities". Current Issues in Language Planning. 14 (2): 231–243. doi:10.1080/14664208.2013.818504. ISSN 1466-4208. S2CID 143367347.

- Wilson, W. H., & Kamanä, K. (2006). For the interest of the hawaiians themselves: Reclaiming the benefits of hawaiian-medium education. Hulili: Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Well-Being, 3(1), 153-181.

- Warner (1996)

- "Hawaiian Language Preschools Garner International Recognition". Indian Country Today Media Network. 2004-05-30. Retrieved 2014-06-07.

- "Hawaiian News: ʻÂhaʻi ʻÔlelo Ola – Hawaii News Now – KGMB and KHNL". Hawaii News Now. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- "KAUAKUKALAHALE archives". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved 2019-01-20.

- Lyovin (1997:258)

- Ramones, Ikaika. "Niʻihau family makes rare public address". Hawaii Independent. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:23)

- Nina Porzucki (2016-07-28). "Meet the last native speakers of Hawaiian". The World (The World in Words podcast).

- Kimura, L., Wilson, W. H., & Kamanä, K. (2003). Hawaiian: back from brink: Honolulu Advertiser

- Wilson, W. H., & Kamanä, K. (2001). Mai loko mai o ka 'i'ini: Proceeding from a dream: The Aha Pûnana Leo connection in Hawaiian language revitalization. In L. Hinton & K. Hale (Eds.), The green book of language revitalization in practice (p. 147-177). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Cook, K. (2000). The hawaiian pepeke system. Rongorongo Studies, 10(2), 46-56.

- "The Kāhulu Pepeke Relative Clause". www.hawaiian-study.info. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- Hinton, Leanne (1999-01-01), "Revitalization of endangered languages", The Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages, Cambridge University Press, pp. 291–311,ISBN 978-0-511-97598-1

- Montgomery-Anderson, B. (2013). Macro-Scale Features of School-Based Language Revitalization Programs. Journal of American Indian Education, 52(3), 41-64.

- "Kawaihuelani Center for Hawaiian Language | 2021-2022 Catalog". Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- Wight (2005:x)

- Schütz (1994:217, 223)

- Schütz (1994:98–133)

- Schütz (1994:110) Plate 7.1

- Schütz (1994:122–126, 173–174)

- Lyovin (1997:259)

- Schütz (1994:223)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:27, 31–32)

- Pukui & Elbert (1986:406)

- Pukui & Elbert (1986:450)

- Pukui & Elbert (1986:257, 281, 451)

- Schütz (1994:146)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:11)

- Pukui & Elbert (1986:62, 275)

- In English, the glottal stop is usually either omitted, or is replaced by a non-phonemic glide, resulting in [hʌˈwai.i] or [hʌˈwai.ji], and [oˈa.hu] or [oˈwa.hu]. Note that the latter two are essentially identical in sound.

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:10, 14, 58)

- Schütz (1994:143)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:11)

- Schütz (1994:144–145)

- Schütz (1994:139–141)

- "Hawaii County Real Property Tax Office". Retrieved 2009-03-03.

This site was designed to provide quick and easy access to real property tax assessment records and maps for properties located in the County of Hawaiʻi and related general information about real property tax procedures.

- "Hawaiian diacriticals". Archived from the original on 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

Over the last decade, there has been an attempt by many well-meaning locals (Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian) to use substitute characters when true diacriticals aren't available. ... This brings me to one of my pet peeves and the purpose of this post: misuse of the backtick (`) character. Many of the previously-mentioned well-intentioned folks mistakenly use a backtick to represent an ʻokina, and it drives me absolutely bonkers.

- "Laʻakea Community". Retrieved 2009-03-03.

Laʻakea Community formed in 2005 when a group of six people purchased Laʻakea Gardens.

- Pukui & Elbert (1986:109, 110, 156, 478)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:14–15)

- Schütz (1994:139, 399)

- Pukui & Elbert (1986:xvii–xviii)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:14, 20–21)

- Schütz (1994:115)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:22–25)

- Kinney (1956)

- Newbrand (1951)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:12–13)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:25–26)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979)

- Parker Jones, ʻŌiwi (April 2018). "Hawaiian". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 48 (1): 103–115. doi:10.1017/S0025100316000438. ISSN 0025-1003. S2CID 232350292.

- Pukui & Elbert (1986) see Hawaiian headwords.

- Schütz (1994:29 4n)

- Pukui & Elbert (1986:386)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:16–18)

- Carter (1996:373)

- Lyovin (1997:268)

- Pukui & Elbert (1986:164, 167)

- Elbert & Pukui (1979:107–108)

- University of Hawaiʻi Press. (2020). ULUKAU: THE HAWAIIAN ELECTRONIC LIBRARY. Hawaiʻi: Author.

- Wong, L. (1999). Authenticity and the Revitalization of Hawaiian. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 30(1), 94-115.

- Grenoble, Lenore A. (2012). Austin, Peter (ed.). "The Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages". Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511975981.002. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

References

- Andrews, Lorrin (1836). A Vocabulary of Words in the Hawaiian Language. Press of the Lahainaluna high school.

- Andrews, Lorrin (1865). A Dictionary of the Hawaiian Language. Notes by William de Witt Alexander. Originally published by Henry M. Whitney, Honolulu, republished by Island Heritage Publishing 2003. ISBN 0-89610-374-9.

- Carter, Gregory Lee (1996). The Hawaiian Copula Verbs He, ʻO, and I, as Used in the Publications of Native Writers of Hawaiian: A Study in Hawaiian Language and Literature (Ph.D. thesis). University of Hawaiʻi.

- Churchward, C. Maxwell (1959). Tongan Dictionary. Tonga: Government Printing Office..

- Dyen, Isidore (1965). "A Lexicostatistical Classification of the Austronesian Languages". Indiana University Publications in Anthropology and Linguistics.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) Memoir 19 of the International Journal of American Linguistics. - Elbert, Samuel H. (1954). "Hawaiian Dictionaries, Past and Future". Hawaiian Historical Society Annual Reports. hdl:10524/68.

- Elbert, Samuel H.; Pukui, Mary Kawena (1979). Hawaiian Grammar. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii. ISBN 0-8248-0494-5.

- Fernández Asensio, Rubèn (2014). "Language policies in the Kingdom of Hawai'i: Reassessing linguicism". Language Problems & Language Planning. John Benjamins Publishing Company. 38 (2): 128–148. doi:10.1075/lplp.38.2.02fer. ISSN 0272-2690.

- Fernández Asensio, Rubèn (2019). "The demise of Hawaiian schools in the 19th century" (PDF). Linguapax Review. Barcelona: Linguapax International. 7: 13–29. ISBN 9788415057123.

- Hinton, Leanne; Hale, Kenneth (2001). The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice. Academic Press.

- Kimura, Larry; Wilson, Pila (1983). "Native Hawaiian Culture". Native Hawaiian Study Commission Minority Report. Washington: United States Department of Interior. pp. 173–203.

- Kinney, Ruby Kawena (1956). "A Non-purist View of Morphomorphemic Variations in Hawaiian Speech". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 65 (3): 282–286. JSTOR 20703564.

- Li, Paul Jen-kuei (2001). "The Dispersal of the Formosan Aborigines in Taiwan" (PDF). Language and Linguistics. 2 (1): 271–278. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-12.

- Li, Paul Jen-kuei (2004). Numerals in Formosan Languages. Taipei: Academia Sinica.

- Lyovin, Anatole V. (1997). An Introduction to the Languages of the World. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN 0-19-508116-1.

- Newbrand, Helene L. (1951). A Phonemic Analysis of Hawaiian (M.A. thesis). University of Hawaiʻi.

- Parker Jones, ʻŌiwi (2009). "Loanwords in Hawaiian". In Haspelmath, M.; Tadmor, U. (eds.). Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 771–789. ISBN 978-3-11-021843-5. Archived from the original on 2010-02-09.

- Parker Jones, ʻŌiwi (2018). "Hawaiian". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 48 (1): 103–115. doi:10.1017/S0025100316000438. S2CID 232350292.

- Pukui, Mary Kawena; Elbert, Samuel H. (1986). Hawaiian Dictionary. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 0-8248-0703-0.

- Ramos, Teresita V. (1971). Tagalog Dictionary. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii. ISBN 0-87022-676-2.

- Schütz, Albert J. (1994). The Voices of Eden: A History of Hawaiian Language Studies. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 0-8248-1637-4.

- U.S. Census (April 2010). "Table 1. Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over for the United States: 2006–2008" (MS-Excel Spreadsheet). American Community Survey Data on Language Use. Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- Warner, Sam L. (1996). I Ola ka ʻŌlelo i nā Keiki: Ka ʻApo ʻia ʻana o ka ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi e nā Keiki ma ke Kula Kaiapuni. [That the Language Live through the Children: The Acquisition of the Hawaiian Language by the Children in the Immersion School.] (Ph.D. thesis). University of Hawaiʻi. OCLC 38455191.

- Wight, Kahikāhealani (2005). Learn Hawaiian at Home. Bess Press. ISBN 1-57306-245-6. OCLC 76789116.

- Wilson, William H. (1976). The O and A Possessive Markers in Hawaiian (M.A. thesis). University of Hawaiʻi. OCLC 16326934.

External links

- Niuolahiki Distance Learning Program (a moodle-based online study program for Hawaiian)

- Ulukau – the Hawaiian electronic library, includes English to/from Hawaiian dictionary

- digitized Hawaiian language newspapers published between 1834 and 1948

- Hawaiian Vocabulary List (from the World Loanword Database)

- Ka Haka ʻUla O Keʻelikōlani, College of Hawaiian Language Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Kulaiwi – learn Hawaiian through distance learning courses

- Hawaiian.saivus.org Archived 2011-11-14 at the Wayback Machine – Detailed Hawaiian Language Pronunciation Guide

- Traditional and Neo Hawaiian: The Emergence of a New Form of Hawaiian Language as a Result of Hawaiian Language Regeneration

- "Hale Pa'i" Article about Hawaiian language newspapers printed at Lahainaluna on Maui. Maui No Ka 'Oi Magazine Vol.12 No.3 (May 2008).

- "Speak Hawaiian"' Article about Hawaiian language resource on iPhone. (May 2010).

- How to Pronounce "Hawai'i", Kelley L. Ross, Ph.D., 2008

- OLAC Resources in and about the Hawaiian language

- " Article about Hawaiian Dictionary resource on iPhone in Honolulu Magazine. (May 2012).