Lethbridge

Lethbridge (/ˈlɛθbrɪdʒ/ LETH-brij) is a city in the province of Alberta, Canada. With a population of 101,482 in its 2019 municipal census, Lethbridge became the fourth Alberta city to surpass 100,000 people. The nearby Canadian Rocky Mountains contribute to the city's warm summers, mild winters, and windy climate. Lethbridge lies southeast of Calgary on the Oldman River.

Lethbridge | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Lethbridge | |

Downtown Lethbridge on 4th Avenue South | |

Flag  Coat of arms Logo | |

| Motto: Ad occasionis januam

"Gateway to Opportunity"[1] | |

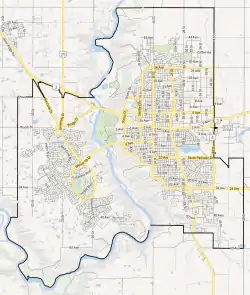

City boundaries | |

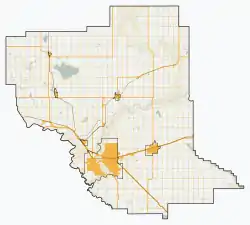

Lethbridge Location in Alberta  Lethbridge Location in Canada  Lethbridge Location in Lethbridge County | |

| Coordinates: 49°41′37″N 112°50′31″W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Alberta |

| Planning region | South Saskatchewan |

| Municipal district | Lethbridge County |

| Incorporated[2] | |

| • Town | November 29, 1890 |

| • City | May 9, 1906 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Blaine Hyggen (Past mayors) |

| • Governing body | Lethbridge City Council

|

| • MP | Rachael Thomas (CPC) |

| • MLAs | Shannon Phillips (NDP), Nathan Neudorf (UCP) |

| • City Manager | Craig Dalton |

| Area (2021)[3] | |

| • Land | 121.12 km2 (46.76 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 64.00 km2 (24.71 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,958.96 km2 (1,142.46 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 910 m (2,990 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 98,406 |

| • Density | 812.5/km2 (2,104/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 92,563 |

| • Metro | 123,847 |

| • Metro density | 41.9/km2 (109/sq mi) |

| • Municipal census (2019) | 101,482[7] |

| • Estimate (2020) | 101,324[8] |

| 1446.2 | |

| Time zone | UTC−07:00 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−06:00 (MDT) |

| Forward sortation areas | T1H–T1K |

| Area code(s) | 403 587, 825, 368 |

| Highways | |

| Waterways | Oldman River |

| GDP (Lethbridge CMA) | CA$6.1 billion (2016)[9] |

| GDP per capita (Lethbridge CMA) | CA$52,243 (2016) |

| Website | Official website |

Lethbridge is the commercial, financial, transportation and industrial centre of southern Alberta. The city's economy developed from drift mining for coal in the late 19th century and agriculture in the early 20th century. Half of the workforce is employed in the health, education, retail and hospitality sectors, and the top five employers are government-based. The only university in Alberta south of Calgary is in Lethbridge, and two of the three colleges in southern Alberta have campuses in the city. Cultural venues in the city include performing art theatres, museums and sports centres.

History

Before the 19th century, the Lethbridge area was populated by several First Nations at various times. The Blackfoot referred to the area as Aksaysim ("steep banks"), Mek-kio-towaghs ("painted rock"), Assini-etomochi ("where we slaughtered the Cree") and Sik-ooh-kotok ("coal"). The Sarcee referred to it as Chadish-kashi ("black/rocks"), the Cree as Kuskusukisay-guni ("black/rocks"), and the Nakoda (Stoney) as Ipubin-saba-akabin ("digging coal").[10] The Kutenai people referred to it as ʔa•kwum.[11]

After the US Army stopped alcohol trading with the Blackfeet Nation in Montana in 1869, traders John J. Healy and Alfred B. Hamilton started a whiskey trading post at Fort Hamilton, near the future site of Lethbridge. The post's nickname became Fort Whoop-Up.[10] The whiskey trade led to the Cypress Hills Massacre of many native Assiniboine in 1873. The North-West Mounted Police, sent to stop the trade and establish order,[10] arrived at Fort Whoop-Up on October 9, 1874. They managed the post for the next 12 years.[10]

Lethbridge's economy developed from drift mines opened by Nicholas Sheran in 1874 and the North Western Coal and Navigation Company in 1882. North Western's president was William Lethbridge, from whom the city derives its name.[12][13] By the turn of the century, the mines employed about 150 men and produced 300 tonnes of coal each day.[10] In 1896, local collieries were the largest coal producers in the Northwest Territories,[14] with production peaking during World War I. An internment camp was set up at the Exhibition Building in Lethbridge from September 1914 to November 1916.[15] After the war, increasing oil and natural gas production gradually replaced coal production,[10] and the last mine in Lethbridge closed in 1957.

The first rail line in Lethbridge was opened on August 28, 1885, by the Alberta Railway and Coal Company,[10] which bought the North Western Coal and Navigation Company five years later.[16] The rail industry's dependence on coal and the Canadian Pacific Railway's efforts to settle southern Alberta with immigrants boosted Lethbridge's economy. After the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) moved the divisional point of its Crowsnest Line from Fort Macleod to Lethbridge in 1905, the city became the regional centre for Southern Alberta.[10] In the mid-1980s, the CPR moved its rail yards in downtown Lethbridge to nearby Kipp, and Lethbridge ceased being a rail hub.[17]

Between 1907 and 1913, a development boom occurred in Lethbridge, making it the main marketing, distribution and service centre in southern Alberta.[10] Such municipal projects as a water treatment plant, a power plant, a streetcar system, and exhibition buildings—as well as a construction boom and rising real estate prices—transformed the mining town into a significant city.[10] Between World War I and World War II, however, the city experienced an economic slump. Development slowed, drought drove farmers from their farms, and coal mining rapidly declined from its peak.[10] After World War II, irrigation of farmland near Lethbridge led to growth in the city's population and economy. Lethbridge College (previously Lethbridge Community College) opened in April 1957 and the University of Lethbridge in 1967.[10]

Geography

The city of Lethbridge is located at 49.7° north latitude and 112.833° west longitude and covers an area of 127.19 square kilometres (49.11 sq mi). It is divided by the Oldman River; its valley has been turned into one of the largest urban park systems in North America at 16 square kilometres (4,000 acres) of protected land.[18] Lethbridge is Alberta's third-largest by population after Calgary and Edmonton. It is the third largest in area after Calgary and Edmonton and is near the Canadian Rockies, 210 kilometres (130 mi) southeast of Calgary.

Lethbridge is split into three geographical areas: north, south and west. The Oldman River separates West Lethbridge from the other two, while Crowsnest Trail and the Canadian Pacific Railway rail line separate North and South Lethbridge.[19] The newest and largest of the three areas, West Lethbridge (pop. 40,898)[7] is home to the University of Lethbridge—which opened at that site in 1971. Although several farms existed on the what is now the Westside, the first housing development was not completed until 1974 and Whoop-Up Drive access opened only in 1975.[20] Much of the city's recent growth has been on the west side, and it has the youngest median age of the three. The north side (pop. 28,172)[7] was originally populated by workers from local coal mines. It has the oldest population of the three areas, is home to multiple industrial parks and includes the former Hamlet of Hardieville, which was annexed by Lethbridge in 1978.[21][22] South Lethbridge (pop. 32,412)[7] is the commercial heart of the city; it contains the downtown core, the bulk of retail and hospitality establishments, and the Lethbridge College.

Climate

Lethbridge has a semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk) with an average maximum temperature of 12.8 °C (55.0 °F) and an average minimum temperature of −1.1 °C (30.0 °F). With precipitation averaging 380.2 mm (14.97 in), and 264 dry days on average, Lethbridge is the eleventh driest city in Canada.[23][24] Mean relative humidity hovers between 69 and 78% in the morning throughout the year, but afternoon mean relative humidity is more uneven, ranging from 38% in August to 58% in January.[25] On average, Lethbridge has 116 days with wind speed of 40 km/h (25 mph) or higher, ranking it as the second city in Canada for such weather.[23]

Its high elevation of 929 m (3,048 ft) and close proximity to the Rocky Mountains provides Lethbridge with cooler summers than other locations in the Canadian Prairies.[26] These factors protect the city from strong northwest and southwest winds and contribute to frequent chinook winds during the winter. Lethbridge winters have the highest temperatures in the prairies, reducing the severity and duration of winter cold periods and resulting in fewer days with snow cover.[27] The average daytime temperature peaks by the end of July/beginning of August, when it reaches 26.4 °C (79.5 °F).[28] The city's temperature reaches a maximum high of 35.0 °C (95.0 °F) or greater on average once or twice a year.[25]

The highest temperature ever recorded in Lethbridge was 40.5 °C (104.9 °F) on August 10, 2018.[29] The lowest temperature ever recorded was −42.8 °C (−45.0 °F) on January 7, 1909, December 18, 1924,[30] January 3, 1950, and December 29, 1968.[25]

| Climate data for Lethbridge Airport, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1886–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 17.3 | 21.8 | 26.3 | 30.2 | 35.4 | 37.7 | 40.9 | 39.8 | 36.1 | 30.1 | 23.0 | 17.8 | 40.9 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

33.9 (93.0) |

34.2 (93.6) |

38.3 (100.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

40.5 (104.9) |

36.7 (98.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

40.5 (104.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0.1 (32.2) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

13.7 (56.7) |

4.8 (40.6) |

0.6 (33.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6 (21) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

12.6 (54.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

5.9 (42.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −12.1 (10.2) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.3 (50.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−11.4 (11.5) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −42.8 (−45.0) |

−42.2 (−44.0) |

−38 (−36) |

−27.2 (−17.0) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−26.7 (−16.1) |

−35.6 (−32.1) |

−42.8 (−45.0) |

−42.8 (−45.0) |

| Record low wind chill | −55 | −51 | −50 | −33 | −16 | −7 | 0 | −3 | −14 | −36 | −47 | −56 | −56 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 13.5 (0.53) |

12.0 (0.47) |

22.8 (0.90) |

28.0 (1.10) |

49.9 (1.96) |

82.0 (3.23) |

42.6 (1.68) |

37.3 (1.47) |

41.4 (1.63) |

20.1 (0.79) |

17.8 (0.70) |

12.9 (0.51) |

380.2 (14.97) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.2 (0.01) |

0.3 (0.01) |

2.3 (0.09) |

15.5 (0.61) |

45.1 (1.78) |

82.0 (3.23) |

42.6 (1.68) |

36.4 (1.43) |

39.5 (1.56) |

10.4 (0.41) |

2.0 (0.08) |

0.5 (0.02) |

276.7 (10.89) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 15.4 (6.1) |

12.9 (5.1) |

22.5 (8.9) |

13.4 (5.3) |

4.8 (1.9) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.8 (0.3) |

1.9 (0.7) |

9.9 (3.9) |

16.7 (6.6) |

14.1 (5.6) |

112.4 (44.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 8.0 | 7.1 | 9.6 | 8.7 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 9.2 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 105.0 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.30 | 0.19 | 1.6 | 5.8 | 10.9 | 11.6 | 9.2 | 8.0 | 8.7 | 4.9 | 1.6 | 0.73 | 63.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 7.8 | 7.1 | 8.7 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.11 | 0.58 | 2.9 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 46.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 110.2 | 147.0 | 186.1 | 233.4 | 277.0 | 290.3 | 322.1 | 297.5 | 228.5 | 189.7 | 119.1 | 106.5 | 2,507.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 41.1 | 51.5 | 50.6 | 56.7 | 58.2 | 59.7 | 65.6 | 66.5 | 60.2 | 56.6 | 43.5 | 41.8 | 54.3 |

| Source: Environment Canada[25][31][30][32][33][34] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 2,072 | — |

| 1906 | 2,313 | +11.6% |

| 1911 | 8,050 | +248.0% |

| 1916 | 9,436 | +17.2% |

| 1921 | 11,097 | +17.6% |

| 1926 | 10,735 | −3.3% |

| 1931 | 13,489 | +25.7% |

| 1936 | 13,523 | +0.3% |

| 1941 | 14,612 | +8.1% |

| 1946 | 16,522 | +13.1% |

| 1951 | 22,947 | +38.9% |

| 1956 | 29,462 | +28.4% |

| 1961 | 35,454 | +20.3% |

| 1966 | 37,186 | +4.9% |

| 1971 | 41,217 | +10.8% |

| 1976 | 46,752 | +13.4% |

| 1981 | 54,072 | +15.7% |

| 1986 | 58,841 | +8.8% |

| 1991 | 60,974 | +3.6% |

| 1996 | 63,053 | +3.4% |

| 2001 | 67,374 | +6.9% |

| 2006 | 74,637 | +10.8% |

| 2011 | 83,517 | +11.9% |

| 2016 | 92,729 | +11.0% |

| 2021 | 98,406 | +6.1% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45] [46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57] | ||

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the City of Lethbridge had a population of 98,406 living in 40,225 of its 42,862 total private dwellings, a change of 6.1% from its 2016 population of 92,729. With a land area of 121.12 km2 (46.76 sq mi), it had a population density of 812.5/km2 (2,104.3/sq mi) in 2021.[3]

At the census metropolitan area (CMA) level in the 2021 census, the Lethbridge CMA had a population of 123,847 living in 48,647 of its 51,735 total private dwellings, a change of 5.5% from its 2016 population of 117,394. With a land area of 2,958.96 km2 (1,142.46 sq mi), it had a population density of 41.9/km2 (108.4/sq mi) in 2021.[6]

The population of the City of Lethbridge according to its 2019 municipal census is 101,482,[7] a change of 1.7% from its 2018 municipal census population of 99,769.[58] With the 2019 municipal census results, the City of Lethbridge became the fourth city in Alberta to surpass 100,000 people.

In the 2016 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the City of Lethbridge had a population of 92,729 living in 37,575 of its 39,867 total private dwellings, a change of 11% from its 2011 population of 83,517. With a land area of 122.09 km2 (47.14 sq mi), it had a population density of 759.5/km2 (1,967.1/sq mi) in 2016.[57] The same census reported that the metropolitan area of Lethbridge was 117,394 in 2016, up from 105,999 in 2011.[59] Subsequent data from Statistics Canada showed that the 2020 metropolitan population was 128,851, an increase of 1.5% over the previous year.[60]

The most commonly observed faith in Lethbridge is Christianity. According to the 2011 National Household Survey, 52,595 residents, representing 65 percent of respondents, indicated they were Christian, down from 76% in 2001.[61][62] Over 32 percent of Lethbridgians reported no religious affiliation, a substantial increase from 22% in 2001.[61] The number of residents reporting other religions, including Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, Jews and Sikhs amounted to 3 percent. For specific denominations, Statistics Canada reported 16,945 Roman Catholics who were 21 percent of the population, and 7,335 members of the United Church of Canada who were about 9 percent of the population.

According to the 2011 census, more than 87 percent of residents spoke English as a first language. Nearly 2 percent spoke German; just over 1 percent each spoke Spanish, Dutch, or French; and almost 1 percent each spoke Chinese (unspecified), Tagalog, Polish, or Hungarian their first language. The next most commonly spoken languages were Japanese, Italian, Ukrainian, Nepali, Cantonese, Vietnamese.[63]

Lethbridge was 12.9% visible minorities and 7.1% aboriginal in 2016. Below is a full break down of the demographics. The city is also the home of the largest Bhutanese community in Canada.[64]

| Canada 2016 Census[65] | Population | % of Total Population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minority group | South Asian | 2,055 | 2.3% |

| Chinese | 1,225 | 1.4% | |

| Black | 1,895 | 2.1% | |

| Filipino | 1,745 | 1.9% | |

| Latin American | 1,510 | 1.7% | |

| Arab | 285 | 0.3% | |

| Southeast Asian | 645 | 0.7% | |

| West Asian | 435 | 0.5% | |

| Korean | 235 | 0.3% | |

| Japanese | 1,310 | 1.4% | |

| Other visible minority | 90 | 0.1% | |

| Mixed visible minority | 260 | 0.3% | |

| Total visible minority population | 11,690 | 12.9% | |

| Aboriginal group | First Nations | 4,635 | 5.1% |

| Métis | 1,955 | 2.2% | |

| Inuit | 60 | 0.1% | |

| Total Aboriginal population | 6,405 | 7.1% | |

| European | 68,525 | 75.7% | |

| Total population | 92,729 | 100% | |

Economy

Lethbridge is southern Alberta's commercial, distribution, financial and industrial centre (although Medicine Hat plays a similar role in southeastern Alberta). It has a trading area population of 341,180, including parts of British Columbia,[26] and provides jobs for up to 86,000 people who commute to and within the city from a radius of 100 kilometres (62 mi).[26]

Lethbridge's economy has traditionally been agriculture-based; however, it has diversified in recent years. Half of the workforce is employed in the health, education, retail and hospitality sectors,[61] and the top five employers are government-based.[66] Several national companies are based in Lethbridge. From its founding in 1935, Canadian Freightways based its head office there until moving operations to Calgary in 1948, though its call centre remains in Lethbridge.[67] Taco Time Canada was based in the city from 1978 to 1995 before moving to Calgary.[68] Minute Muffler, which began in 1969, is based in Lethbridge.[69] International shipping company H & R Transport has been based in the city since 1955.[70] Braman Furniture, which has locations in Manitoba and Ontario, was headquartered in Lethbridge from 1991 to 2008.[71]

Lethbridge serves as a hub for commercial activity in the region by providing services and amenities. Many transport services, including Red Arrow buses, four provincial highways, rail service and an airport, are concentrated in or near the city. In 2004, the police services of Lethbridge and Coaldale combined to form the Lethbridge Police Service.[72] Lethbridge provides municipal water to Coaldale, Coalhurst, Diamond City, Iron Springs, Monarch, Shaughnessy and Turin.[73][74]

In 2002, the municipal government organized Economic Development Lethbridge, a body responsible for promoting and developing the city's commercial interests.[75] Two years later, the city joined in a partnership with 24 other local communities to create an economic development alliance called SouthGrow, representing a population of over 140,000.[76] In 2006, Economic Development Lethbridge partnered with SouthGrow Regional Initiative and Alberta SouthWest Regional Alliance to create the Southern Alberta Alternative Energy Partnership. This partnership promotes business related to alternative energy, including wind power, solar power and biofuel, in the region.[77]

Arts and culture

Lethbridge was designated a Cultural Capital of Canada for the 2004–2005 season.[78] The Southern Alberta Ethnic Association (Multicultural Heritage Centre) promotes multiculturalism and ethnic heritage in the community.[79]

The city is home to venues and organizations promoting the arts. Founded in 1958, the Allied Arts Council of Lethbridge is the largest organization in the city dedicated to preserving and enhancing the local arts.[80] In the spring of 2007, the Allied Arts Council Facilities Steering Committee initiated the Arts Re:Building Together Campaign, a grass roots campaign initiative to raise awareness and support for improving arts facilities in Lethbridge. The campaign identified three arts buildings: the Yates Memorial Centre, the Bowman Arts Centre, and the Southern Alberta Art Gallery as cornerstone facilities in the community requiring care and attention. On July 14, 2007, the Finance Committee of City Council approved four arts capital projects for inclusion in the city's Ten Year Capital Plan.[81] Under the campaign to 2010, the renovation and expansion of the Southern Alberta Art Gallery was completed,[82] a new Community Arts Centre will be built in downtown Lethbridge,[83] the City of Lethbridge has a Public Art Program,[84] and a committee was formed to research the possibility of a new Performing Arts Centre in Lethbridge.[85]

Lethbridge has a public library and three major museum/galleries. The Southern Alberta Art Gallery is a contemporary gallery; the community arts centre Casa, administered by the Allied Arts Council; and the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery produces contemporary exhibitions including works from its extensive collection of Canadian, American and European art.[79]

The city is also home to the Lethbridge Symphony, which was founded in 1960 and incorporated as a non-profit in 1961. It has produced several spin-off music groups, including the Southern Alberta Chamber Orchestra, and the still-active Lethbridge Musical Theatre,[86] which produces an annual show. Vox Musica, which traces its roots back to 1968, is a community choir previously based at the University of Lethbridge. As a fully independent non-profit society, Vox Musica continues to rehearse and perform at Southminster United Church and around the community. Theatrical productions are presented by the University of Lethbridge's drama department and New West Theatre, which performs at the Genevieve E. Yates Memorial Centre using its two theatres: the 500-seat proscenium Yates Theatre and the 180-seat black box Sterndale Bennett Theatre.[87]

Attractions

The city, which began as a frontier town, has several historical attractions. The Lethbridge Viaduct, commonly known as the High Level Bridge, is the longest and highest steel trestle bridge in North America.[88] It was completed in 1909 on what was then the city's western edge.[89] Indian Battle Park, in the coulees of the Oldman River, commemorates the last battle between the Cree and the Blackfoot First Nations in 1870.[90]

Originally known as Fort Hamilton, Fort Whoop-Up was a centre of illegal activities during the late 19th century. It was first built in 1869 by J.J. Healy and A.B. Hamilton as a whiskey post and was destroyed by fire a year later. A second, sturdier structure later replaced the fort.[91]

As the cultural centre of southern Alberta, Lethbridge has notable cultural attractions. Nikka Yuko Japanese Garden in south Lethbridge was opened in 1967 as part of a Canadian centennial celebration attended by Japan's Prince and Princess Takamatsu.[92] The Galt Museum & Archives is the largest museum in the Lethbridge area; the building housing the museum served as the city's main hospital during the late 19th century and early 20th centuries. Several other important attractions are based in Lethbridge, including the Lethbridge Military Museum[93] and the Helen Schuler Nature Centre which educates about the river bottom and coulees.[94][95]

Several structures such as the historic post office are prominent on the skyline of Lethbridge. Less well-known than the High Level Bridge, the post office is one of the most distinctive buildings in Lethbridge. Built in 1912, the four-storey structure is crowned by a functioning clock tower.[96] Other prominent buildings include office towers; the water tower, which was originally built in 1958 and sold to a private developer who converted it into a restaurant;[97] and the Alberta Terminals grain elevators.

From March 2018 to August 2020, Lethbridge was home to ARCHES, 24-hour supervised drug use site. It was the busiest SCS in North America with 663 visits a day. The Star called it a "new landmark". The SCS featured injection drug and inhalation drug facilities[98] and it was a subject of disagreement by the nearby business community.[99][100] The site closed at the end of August 2020 after the province removed grant funding following discovery of misappropriation of public funds.[101]

Sports and recreation

Lethbridge has designated 16 percent of the land within city boundaries as parkland, including the 755 hectares (1,870 acres) Oldman River valley parks system.[102] It has facilities for field sports, numerous baseball diamonds, the Spitz Stadium,[103] the Nicholas Sheran Park (a disc golf course), two skateparks, a BMX track, a climbing wall, a dozen tennis courts, and seven pools. It is home to five golf courses, including the award-winning Paradise Canyon Golf Resort, and is within 30 km (19 mi) of several others.[79]

Built for the 1975 Canada Games, the ENMAX Centre is Lethbridge's multipurpose arena. The 6,500-seat facility has hosted concerts, three-ring circuses, multicultural events, national curling championships, basketball events, banquets, skating events and is home to the Lethbridge Hurricanes, a major Western Hockey League franchise. The arena has a running track, racquetball and squash courts, and a full-size ice rink.[104] In 1997, the 58,000-square-foot (5,400 m2) Servus Sports Centre (originally the Lethbridge Soccer Centre) was built directly south of the ENMAX Centre and added two regulation size indoor soccer pitches to the complex.[105] The Lethbridge Kyodokan Judo Club facility is located next to the Community Savings Place, and has been a Judo Canada Regional Training Centre since 2015.[106]

On the city's west side, Phase 1 of the ATB Centre, a recreation complex, opened in 2016 and houses two hockey rinks and the Lethbridge Curling Club.[107] Phase 2 of this project opened in May 2019 [108] and includes a field house with basketball courts and a 300m running track, as well as an aquatics centre with slides and a wave pool.

Several winter sports venues are in or near Lethbridge. The city has six indoor ice arenas with a total ice area of 11,220 square metres (120,800 sq ft) and a total seating capacity of 8,149. Other than the ENMAX Centre, all ice surfaces are available from October to April only. Lethbridge is 150 kilometres (93 mi) east of the Castle Mountain ski resort.[79]

In October 2020, the Canadian Junior Football League (CJFL) announced an expansion team would begin play in Lethbridge at the 3,500-seat University of Lethbridge Stadium in 2022. The Lethbridge Vipers will be the seventh team in the Prairie Junior Football Conference and the 19th team in the CJFL.

| Team | Sport | League |

|---|---|---|

| Lethbridge Bulls | Baseball | Western Major Baseball League |

| Lethbridge Eagles | Hockey | Alberta Junior Female Hockey League |

| Lethbridge Hurricanes | Hockey | Western Hockey League |

| Lethbridge Vipers | Canadian Football | Canadian Junior Football League[109] |

Government

Eight councillors and a mayor make up the Lethbridge City Council. City voters elect a new government every four years. The last election was October 18, 2021. Lethbridge does not have a ward system, so the mayor and all councillors are elected at large.[110] The 2009–2011 operating budget of the City of Lethbridge was CA$250–278 million, more than half of which came from property tax.[111] One Member of Parliament (MP) representing Lethbridge sits in the House of Commons in Ottawa, and two members of Alberta's legislative assembly (MLAs), representing Lethbridge-East (UCP) and Lethbridge-West (NDP), sit in the legislative assembly in Edmonton.

Traditionally, political leanings in Lethbridge have been right-wing. Federally, from 1917 to 1930, Lethbridge voters switched between various federal parties,[112] but from 1935 to 1957, they voted Social Credit in each election.[112] Progressive Conservatives held office from 1958 until 1993, when the Reform Party of Canada was formed.[112][113][114] The Reform party and its various subsequent incarnations such as the current Conservative Party of Canada have dominated the polls since.[114] The city's two provincial electoral districts are represented by one government MLA, currently Nathan Neudorf for Lethbridge-East,[115] and one opposition MLA, currently Shannon Phillips for Lethbridge-West.[116]

Alberta Health Services, the provincial health authority that plans and delivers health services on behalf of the Ministry of Health, administers public health services in Lethbridge. Chinook Health oversees facilities in southwestern Alberta, such as the Chinook Regional Hospital and St. Michael's Health Centre.

Transportation

Mass transit in Lethbridge consists of 40 buses (with an average age of 10 years) operating on more than a dozen routes.[117] Traditionally, bus routes in the city started and ended downtown. In the early 21st century, however, Lethbridge Transit introduced cross-town and shuttle routes, such as University of Lethbridge to Lethbridge College, University of Lethbridge to the North Lethbridge terminal, and Lethbridge College to the North Lethbridge terminal. Several routes converge near the Chinook Regional Hospital, although it is not officially a terminal.

The Parks and Recreation department maintains the citywide, 30-kilometre (19 mi) pedestrian/cyclist Coal Banks Trail system (map). The system was designed to connect the Oldman River valley with other areas of the city, including Pavan Park in the north, Henderson Lake in the east, Highways 4 and 5 in the south and a loop in West Lethbridge (including University Drive and McMaster Blvd).[118]

Four provincial highways (3, 4, 5, and 25) run through or terminate in Lethbridge.[119] This has led to the creation of major arterial roads, including Mayor Magrath Drive, University Drive and Scenic Drive.[120] This infrastructure and its location on the CANAMEX Corridor has helped make Lethbridge and its freight depots a major shipping destination.[27] Lethbridge is 100 kilometres (62 mi) north of the United States border via Highways 4 and 5 and 210 kilometres (130 mi) south of Calgary via Highways 2 and 3. Highways 2, 3 and 4 form part of the CANAMEX trade route between Mexico, the United States, and Canada.[27]

Lethbridge has a commercial airport, the Lethbridge Airport, and the CPR rail yards in Kipp, Alberta (12 km away). The airport provides commercial flights to Calgary, industrial and corporate opportunities, as well as private and charter flights elsewhere. The airport provides customs services for flights arriving from the United States. The rail yards were moved to Kipp, just west of the city, from downtown Lethbridge in 1983.[121][122] The yards were planned for redevelopment with a mix of multi-family residential, commercial and light industrial land uses.[123] The Park Place Mall is now located on the portion of the former rail yards north of 1 Avenue South between Scenic Drive to the west and Stafford Drive to the east.[124]

Education

The Lethbridge School Division and the separate Holy Spirit Roman Catholic School Division administer grades kindergarten through 12 locally. The Palliser School Division, which is based in Lethbridge, administers public primary and secondary education in the outlying areas. Lethbridge School Division administers five high schools (Chinook High School, Immanuel Christian High School, Lethbridge Collegiate Institute, Victoria Park High School, and Winston Churchill High School), four middle schools, and 14 elementary schools in Lethbridge.[125] Immanuel Christian covers grades 6 through 12.

Lethbridge is home to Lethbridge College, founded in 1957, and the University of Lethbridge, founded in 1967. Red Crow Community College has a campus in the city. During the 2015–2016 school year, the University of Lethbridge and the Lethbridge College had a combined enrolment of 14,820, which represented 20 percent of the city's population.[126]

Media

Lethbridge has two major newspapers: the daily Lethbridge Herald and the weekly Lethbridge Sun Times. The university and college each have a student-run, weekly newspaper. There are 11 FM radio stations, including CKXU-FM, a campus radio station located at the University of Lethbridge.

See also

- List of communities in Alberta

- List of cities in Alberta

- List of people from Lethbridge

References

- City of The Lethbridge. "City of Lethbridge Crest/Coat of Arms". Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Location and History Profile: City of Lethbridge" (PDF). Alberta Municipal Affairs. June 17, 2016. p. 78. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities)". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- "Alberta Private Sewage Systems 2009 Standard of Practice Handbook: Appendix A.3 Alberta Design Data (A.3.A. Alberta Climate Design Data by Town)" (PDF) (PDF). Safety Codes Council. January 2012. pp. 212–215 (PDF pages 226–229). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- "Population and dwelling counts: Canada and population centres". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- "Census Results 2019". City of Lethbridge. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- "Census Subdivision (Municipal) Population Estimates, July 1, 2016 to 2020, Alberta". Alberta Municipal Affairs. March 23, 2021. Archived from the original on April 1, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- "Table 36-10-0468-01 Gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, by census metropolitan area (CMA) (x 1,000,000)". Statistics Canada. January 27, 2017. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- Greg Ellis (October 2001). "A Short History of Lethbridge, Alberta". Archived from the original on September 23, 2005. Retrieved January 17, 2007.

- "FirstVoices: Nature / Environment—place names: words. Ktunaxa". Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- "Indian Battle Park". City of Lethbridge. Archived from the original on August 28, 2004. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- Place-names of Alberta. Ottawa: Geographic Board of Canada. 1928. p. 76. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- "City of Lethbridge website". Archived from the original on December 17, 2005.

- "Internment Camps in Canada during the First and Second World Wars, Library and Archives Canada". June 11, 2014. Archived from the original on September 5, 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- "Alphabetical list of Private Acts—Railways". Table of Private Acts (1867 to December 31, 2013), Railways. Department of Justice Canada. November 27, 2014. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- "Executive Summary" (PDF). Highways 3 & 4, Lethbridge and Area NHS & NSTC, Functional Planning Study, #R – 970. Stantec Consulting Ltd. February 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- "Field Guide Booklet" (PDF). The Lethbridge Naturalists Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- Ellis, Faron (November 2004). "Alberta Provincial Election Study" (PDF). Citizen-Society Research Lab. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 29, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- Ian MacLachlan (March 11, 2005). "Whiskey Traders, Coal Miners, Cattle Ranchers and a Few Bordellos". Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- The Local Authorities Board (December 23, 1977). "Order No. 10079" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- "Hardieville/Legacy Ridge/Uplands Area Structure Plan" (PDF). UMA Engineering Ltd. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- Weather Winners, Environment Canada. Retrieved January 7, 2011. Archived March 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Lethbridge CDA, Alberta". Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000. Environment Canada. February 4, 2013. Archived from the original on November 20, 2012. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- "Lethbridge A, Alberta". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Lethbridge Trade Area and Commercial Catchment Study Archived November 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Economic Development Lethbridge. 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- Community Profile, Lethbridge Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved December 24, 2006.

- "Climate Data Almanac for August 02". Environment Canada. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- "Daily Data Report for August, 2018". Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on September 7, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- "Lethbridge CDA". Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000. Environment Canada. January 19, 2011. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- "Lethbridge". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- "Lethbridge A, Alberta". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on March 11, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- "April 1910". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- "January 2015". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on December 11, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- "Table IX: Population of cities, towns and incorporated villages in 1906 and 1901 as classed in 1906". Census of the Northwest Provinces, 1906. Vol. Sessional Paper No. 17a. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1907. p. 100.

- "Table I: Area and Population of Canada by Provinces, Districts and Subdistricts in 1911 and Population in 1901". Census of Canada, 1911. Vol. I. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1912. pp. 2–39.

- "Table I: Population of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta by Districts, Townships, Cities, Towns, and Incorporated Villages in 1916, 1911, 1906, and 1901". Census of Prairie Provinces, 1916. Vol. Population and Agriculture. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1918. pp. 77–140.

- "Table 8: Population by districts and sub-districts according to the Redistribution Act of 1914 and the amending act of 1915, compared for the census years 1921, 1911 and 1901". Census of Canada, 1921. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1922. pp. 169–215.

- "Table 7: Population of cities, towns and villages for the province of Alberta in census years 1901–26, as classed in 1926". Census of Prairie Provinces, 1926. Vol. Census of Alberta, 1926. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1927. pp. 565–567.

- "Table 12: Population of Canada by provinces, counties or census divisions and subdivisions, 1871–1931". Census of Canada, 1931. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1932. pp. 98–102.

- "Table 4: Population in incorporated cities, towns and villages, 1901–1936". Census of the Prairie Provinces, 1936. Vol. I: Population and Agriculture. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1938. pp. 833–836.

- "Table 10: Population by census subdivisions, 1871–1941". Eighth Census of Canada, 1941. Vol. II: Population by Local Subdivisions. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1944. pp. 134–141.

- "Table 6: Population by census subdivisions, 1926–1946". Census of the Prairie Provinces, 1946. Vol. I: Population. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1949. pp. 401–414.

- "Table 6: Population by census subdivisions, 1871–1951". Ninth Census of Canada, 1951. Vol. I: Population, General Characteristics. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1953. p. 6.73–6.83.

- "Table 6: Population by sex, for census subdivisions, 1956 and 1951". Census of Canada, 1956. Vol. Population, Counties and Subdivisions. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1957. p. 6.50–6.53.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2011 and 2006 censuses". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2012. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- "Table 6: Population by census subdivisions, 1901–1961". 1961 Census of Canada. Series 1.1: Historical, 1901–1961. Vol. I: Population. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1963. p. 6.77–6.83.

- "Population by specified age groups and sex, for census subdivisions, 1966". Census of Canada, 1966. Vol. Population, Specified Age Groups and Sex for Counties and Census Subdivisions, 1966. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1968. p. 6.50–6.53.

- "Table 2: Population of Census Subdivisions, 1921–1971". 1971 Census of Canada. Vol. I: Population, Census Subdivisions (Historical). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1973. p. 2.102–2.111.

- "Table 3: Population for census divisions and subdivisions, 1971 and 1976". 1976 Census of Canada. Census Divisions and Subdivisions, Western Provinces and the Territories. Vol. I: Population, Geographic Distributions. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1977. p. 3.40–3.43.

- "Table 4: Population and Total Occupied Dwellings, for Census Divisions and Subdivisions, 1976 and 1981". 1981 Census of Canada. Vol. II: Provincial series, Population, Geographic distributions (Alberta). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1982. p. 4.1–4.10. ISBN 0-660-51095-2.

- "Table 2: Census Divisions and Subdivisions—Population and Occupied Private Dwellings, 1981 and 1986". Census Canada 1986. Vol. Population and Dwelling Counts—Provinces and Territories (Alberta). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1987. p. 2.1–2.10. ISBN 0-660-53463-0.

- "Table 2: Population and Dwelling Counts, for Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions, 1986 and 1991—100% Data". 91 Census. Vol. Population and Dwelling Counts—Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1992. pp. 100–108. ISBN 0-660-57115-3.

- "Table 10: Population and Dwelling Counts, for Census Divisions, Census Subdivisions (Municipalities) and Designated Places, 1991 and 1996 Censuses—100% Data". 96 Census. Vol. A National Overview—Population and Dwelling Counts. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1997. pp. 136–146. ISBN 0-660-59283-5.

- "Population and Dwelling Counts, for Canada, Provinces and Territories, and Census Divisions, 2001 and 1996 Censuses—100% Data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on August 21, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2006 and 2001 censuses—100% data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. January 6, 2010. Archived from the original on May 28, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2016 and 2011 censuses—100% data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List (PDF). Alberta Municipal Affairs. December 2018. ISBN 978-1-4601-4254-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 19, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Census Profile, 2016 Census—Lethbridge [Census metropolitan area], Alberta and Alberta [Province]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- Franklin, Michael (January 14, 2021). "Calgary's population grew by almost 2% last year: StatCan report". Calgary. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- Lethbridge Community Profile. Archived December 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Statistics Canada. 2002. 2001 Community Profiles. Released June 27, 2002. Last modified: December 14, 2006. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 93F0053XIE

- "NHS Profile, Lethbridge, CY, Alberta, 2011", Statistics Canada, May 8, 2013, archived from the original on January 5, 2016.

- "Lethbridge, Alberta (Code 4802012) and Division No. 2, Alberta (Code 4802) (table)". 2011 Census. Statistics Canada. October 24, 2012. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- "Lethbridge home to the largest Bhutanese community in Canada | Globalnews.ca". Global News. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- "Lethbridge, City [Census subdivision], Alberta and Division No. 2, Census division [Census division], Alberta". Statistics Canada. June 21, 2019. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- "Major employers of Lethbridge—2005". Economic Development Lethbridge. Archived from the original on August 23, 2006. Retrieved August 2, 2006.

- Company History, Canadian Freightways. Retrieved December 24, 2006. Archived October 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Company History, Taco Time Canada. Retrieved December 24, 2006.

- The First 30 Years, Minute Muffler & Brake. Retrieved December 24, 2006. Archived October 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Company History, H & R Transport. Retrieved December 24, 2006. Archived September 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Braman Furniture International, Canadian Company Capabilities, Industry Canada. Last Updated: November 9, 2005.

- Police Commission, Lethbridge Regional Police Service. Retrieved December 24, 2006. Archived January 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Pipeline Project Flows Along". Sunny South News. March 14, 2002.

- "Monarch to tap into Lethbridge water". Lethbridge Herald. February 23, 2008.

- About Economic Development Lethbridge Archived October 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved December 24, 2006.

- Annual Report 2006 Archived September 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, SouthGrow. June 21, 2006.

- Southern Alberta Economic Development Organizations Partner to Launch Major Alternative Energy Initiative Archived March 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Southern Alberta Alternative Energy Partnership news release. November 6, 2006.

- Cultural Capitals of Canada, Canadian Heritage. Retrieved December 24, 2006.

- "Recreation & Leisure". Choose Lethbridge. Economic Development Lethbridge. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- "About Us". Allied Arts Council of Lethbridge. Archived from the original on February 13, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- "Arts Facilities". Allied Arts Council. Archived from the original on July 27, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- "Southern Alberta Art Gallery". Allied Arts Council. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- "Community Arts Centre". Allied Arts Council. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- "Public Art". Allied Arts Council. Archived from the original on December 14, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- "Performing Arts Centre". Allied Arts Council. Archived from the original on December 16, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- Nelson, Margaret; Philip M. Wults. "Lethbridge, Alta". Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. Historica. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- "About Us". New West Theatre. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- Forth Junction Project. "Alberta's largest railway bridges". Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- "High Level Bridge". City of Lethbridge. Archived from the original on May 18, 2006. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- "Lethbridge". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on December 27, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- Allen, Robert. "Fort Whoop-Up". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on May 18, 2006. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- Neugebauer, Dierk (January 2003). "Nikka Yuko—A Special Place". The Journal. Toronto Bonsai Society. Archived from the original on September 26, 2006. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- "The Lethbridge Military Museum – Celebrating the rich military history of Lethbridge and area". www.lethbridgemilitarymuseum.org. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- "Our History". Galt Museum & Archives. Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- "Friends of Helen Schuler Nature Centre Society". Friends of Helen Schuler Nature Centre Society. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- "Buildings". City of Lethbridge. Archived from the original on February 22, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- "Landmarks". City of Lethbridge. Archived from the original on April 2, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- Yousif, Nadine (August 18, 2019). "A small Alberta city is home to the busiest drug consumption site in North America. We spent 12 hours inside". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- "As downtown Lethbridge safe consumption site works to minimize impact, business owners rally over concerns". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- Boyd, Alex (August 31, 2020). "On International Overdose Awareness Day, the busiest supervised consumption site in North America closes under a cloud of scandal". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- Goulet, Justin. "ARCHES ceases supervised consumption services in Lethbridge". Lethbridge News Now. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- Stantec Consulting (March 2007). "Bikeways and Pathways Master Plan". City of Lethbridge. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- "The Official Website of the Lethbridge Bulls: Home". www.bullsbaseball.com. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- "ENMAX Centre". City of Lethbridge. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- "Lethbridge Soccer Centre". City of Lethbridge. Archived from the original on September 3, 2004. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- "Judo Canada Regional Training Centre Lethbridge". Judo Alberta. Archived from the original on November 14, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- "ATB Centre". www.lethbridge.ca. Archived from the original on November 14, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- "ATB Centre – Phase 2 (D-6)". www.lethbridge.ca. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- Gunn, Connor. "New Junior Football Club starting in Lethbridge". Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- "City Council". City of Lethbridge. Archived from the original on May 25, 2006. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- 2009–2011 Operating Budget Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, City of Lethbridge

- "Lethbridge, Alberta (1914–1977)". History of Federal Ridings since 1867. Parliament of Canada. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- "Lethbridge—Foothills, Alberta (1977–1987)". History of Federal Ridings since 1867. Parliament of Canada. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- "Lethbridge, Alberta (1987 -)". History of Federal Ridings since 1867. Parliament of Canada. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- "Alberta election: Lethbridge-West results". Global News. March 17, 2019. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- "Alberta election: Lethbridge-East results". Global News. March 17, 2019. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- Mabell, Dave (September 9, 2006). "Richard keeps the city's buses on the road". Lethbridge Herald. p. A4.

- "Coal Banks Trail". City of Lethbridge. Archived from the original on September 7, 2004. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- "2016 Provincial Highway 1–216 Progress Chart" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. March 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- "Information Map" (PDF). City of Lethbridge. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- "Rail relocation plans advanced". The Lethbridge Herald. November 6, 1981.

- Scott, Peter (September 17, 1981). "Highway realignment plan gets favorable response". The Lethbridge Herald. p. B1.

- "Railway Relocation Lands Area Redevelopment Plan" (PDF) (PDF). City of Lethbridge. January 1983. p. 80 (Land Use Concept). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- "Information Map" (PDF) (PDF). City of Lethbridge. June 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- "Our Schools". www.lethsd.ab.ca. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- "2016–2023 Lethbridge Community Outlook" (PDF). City of Lethbridge. p. 55. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

Further reading

- Johnston, Alex (1985). Lethbridge: a centennial history. Lethbridge: City of Lethbridge and the Whoop-Up Country Chapter, Historical Society of Alberta. ISBN 978-0-919224-42-1.

- Johnston, Alex (1997). Lethbridge: from coal town to commercial centre : a business history. Lethbridge: Lethbridge Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-9696100-8-3.