Li Bai

Li Bai (Chinese: 李白; pinyin: Lǐ Bái, 701–762), also known as Li Bo, courtesy name Taibai (Chinese: 太白), was a Chinese poet, acclaimed from his own time to the present as a brilliant and romantic figure who took traditional poetic forms to new heights. He and his friend Du Fu (712–770) were two of the most prominent figures in the flourishing of Chinese poetry in the Tang dynasty, which is often called the "Golden Age of Chinese Poetry". The expression "Three Wonders" denotes Li Bai's poetry, Pei Min's swordplay, and Zhang Xu's calligraphy.[1]

Li Bai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

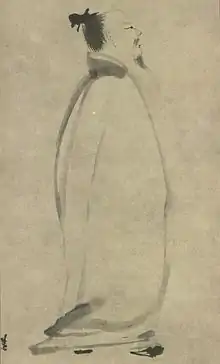

Li Bai Strolling, by Liang Kai (1140–1210) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native name | 李白 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 701 Suiye, Tang China (now Chuy Region, Kyrgyzstan) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 762 (60–61) Dangtu, Tang China (now Ma'anshan, Anhui, China) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Poet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literary movement | Tang poetry | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 李白 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taibai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 太白 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Qinglian Jushi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 青蓮居士 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 青莲居士 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Lotus Householder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Lý Bạch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 이백 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 李白 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 李白 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | りはく | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Around 1000 poems attributed to Li are extant. His poems have been collected into the most important Tang dynasty poetry, Heyaue yingling ji,[2] compiled in 753 by Yin Fan. Thirty-four of Li Bai’s poems are included in the anthology Three Hundred Tang Poems, which was first published in the 18th century.[3] Around the same time, translations of his poems began to appear in Europe. The poems were models for celebrating the pleasures of friendship, the depth of nature, solitude, and the joys of drinking wine. Among the most famous are "Waking from Drunkenness on a Spring Day", "The Hard Road to Shu", and "Quiet Night Thought", which are still taught in schoolbooks in China. In the West, multilingual translations of Li's poems continue to be made. His life has even taken on a legendary aspect, including tales of drunkenness, chivalry, and the well-known tale that Li drowned when he reached from his boat to grasp the moon's reflection in the river while drunk.

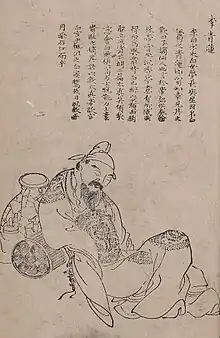

Much of Li's life is reflected in his poetry, the poems are about places he visited, friends whom he saw off on journeys to distant locations perhaps never to meet again, his own dream-like imaginations embroidered with shamanic overtones, current events of which he had news, descriptions taken from nature in a timeless moment of poetry, and so on. However, of particular importance are the changes in the times through which he lived. His early poetry took place in the context of a "golden age" of internal peace and prosperity in the Tang dynasty, under the reign of an emperor who actively promoted and participated in the arts. This ended with the beginning with the rebellion of general An Lushan. His rebellion lead most of Northern China to be devastated by war and famine. Li's poetry during this period has taken new tones and qualities. Unlike his younger friend Du Fu, Li did not live to see the end of the chaos. However, much of Li's poetry has survived, retaining enduring popularity in mainland China and Taiwan. Li Bai is depicted in the Wu Shuang Pu (無雙譜, Table of Peerless Heroes) by Jin Guliang.

Names

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Chinese: | 李白 |

| Pinyin: | Lǐbaí or Li Bo |

| Zi (字): | Taìbaí (Tai-pai; 太白) |

| Hao (號): | Qinglian Jushi (Ch'ing-lien Chu-shih; traditional Chinese: 青蓮居士; simplified Chinese: 青莲居士) |

| aka: | Shixian (traditional Chinese: 詩仙; simplified Chinese: 诗仙; Wade–Giles: Shih-hsien) The Poet Saint Immortal Poet |

Li Bai's name has been romanized as Li Bai, Li Po, Li Bo (romanizations of Standard Chinese pronunciations), and Ri Haku (a romanization of the Japanese pronunciation).[4] The varying Chinese romanizations are due to the facts that his given name (白) has two pronunciations in Standard Chinese: the literary reading bó (Wade–Giles: po2) and the colloquial reading bái; and that earlier authors used Wade–Giles while modern authors prefer pinyin. The reconstructed version of how he and others during the Tang dynasty would have pronounced this is Bhæk. His courtesy name was Taibai (太白), literally "Great White", as the planet Venus was called at the time. This has been romanized variously as Li Taibo, Li Taibai, Li Tai-po, among others. The Japanese pronunciation of his name and courtesy name may be romanized as "Ri Haku" and "Ri Taihaku" respectively.

He is also known by his art name (hao) Qīnglián Jūshì (青蓮居士), meaning Householder of Azure Lotus, or by the nicknames "Immortal Poet" (Poet Transcendent; Wine Immortal (Chinese: 酒仙; pinyin: Jiuxiān; Wade–Giles: Chiu3-hsien1), Banished Transcendent (Chinese: 謫仙人; pinyin: Zhéxiānrén; Wade–Giles: Che2-hsien1-jen2), Poet-Knight-errant (traditional Chinese: 詩俠; simplified Chinese: 诗侠; pinyin: Shīxiá; Wade–Giles: Shih1-hsia2, or "Poet-Hero").

Life

The two "Books of Tang", The Old Book of Tang and The New Book of Tang, remain the primary sources of bibliographical material on Li Bai.[5] Other sources include internal evidence from poems by or about Li Bai, and certain other sources, such as the preface to his collected poems by his relative and literary executor, Li Yangbin.

Background and birth

Li Bai is generally considered to have been born in 701, in Suyab (碎葉) of ancient Chinese Central Asia (present-day Kyrgyzstan),[6] where his family had prospered in business at the frontier.[7] Afterwards, the family under the leadership of his father, Li Ke (李客), moved to Jiangyou (江油), near modern Chengdu, in Sichuan, when the youngster was about five years old. There is some mystery or uncertainty about the circumstances of the family's relocations, due to a lack of legal authorization which would have generally been required to move out of the border regions, especially if one's family had been assigned or exiled there.

Background

Two accounts given by contemporaries Li Yangbing (a family relative) and Fan Chuanzheng state that Li's family was originally from what is now southwestern Jingning County, Gansu. Li's ancestry is traditionally traced back to Li Gao, the noble founder of the state of Western Liang.[8] This provides some support for Li's own claim to be related to the Li dynastic royal family of the Tang dynasty: the Tang emperors also claimed descent from the Li rulers of West Liang. This family was known as the Longxi Li lineage (隴西李氏). Evidence suggests that during the Sui dynasty, Li's own ancestors, at that time for some reason classified socially as commoners, were forced into a form of exile from their original home (in what is now Gansu) to some location or locations further west.[9] During their exile in the far west, the Li family lived in the ancient Silk Road city of Suiye (Suyab, now an archeological site in present-day Kyrgyzstan), and perhaps also in Tiaozhi (simplified Chinese: 条枝; traditional Chinese: 條枝; pinyin: Tiáozhī), a state near modern Ghazni, Afghanistan.[10] These areas were on the ancient Silk Road, and the Li family were likely merchants.[11] Their business was quite prosperous.[12]

Birth

In one hagiographic account, while Li Bai's mother was pregnant with him, she had a dream of a great white star falling from heaven. This seems to have contributed to the idea of his being a banished immortal (one of his nicknames).[13] That the Great White Star was synonymous with Venus helps to explain his courtesy name: "Tai Bai", or "Venus".

Marriage and family

Li is known to have married four times. His first marriage, in 727, in Anlu, Hubei, was to the granddaughter of a former government minister.[7] His wife was from the well-connected Wú (吳) family. Li Bai made this his home for about ten years, living in a home owned by his wife's family on Mt. Bishan (碧山).[14] In 744, he married for the second time in what now is the Liangyuan District of Henan. This marriage was to another poet, surnamed Zong (宗), with whom he both had children[15] and exchanges of poems, including many expressions of love for her and their children. His wife, Zong, was a granddaughter of Zong Chuke (宗楚客, died 710), an important government official during the Tang dynasty and the interregnal period of Wu Zetian.

Early years

In 705, when Li Bai was four years old, his father secretly moved his family to Sichuan, near Chengdu, where he spent his childhood.[16] Currently, there is a monument commemorating this in Zhongba Town, Jiangyou, Sichuan province (the area of the modern province then being known as Shu, after a former independent state which had been annexed by the Sui dynasty and later incorporated into the Tang dynasty lands). The young Li spent most of his growing years in Qinglian (青莲; lit. "Blue [also translated as 'green', 'azure', or 'nature-coloured'] Lotus"), a town in Chang-ming County, Sichuan, China.[7] This now nominally corresponds with Qinglian Town (青蓮鎮) of Jiangyou County-level city, in Sichuan.

The young Li read extensively, including Confucian classics such as The Classic of Poetry (Shijing) and the Classic of History (Shujing), as well as various astrological and metaphysical materials which Confucians tended to eschew, though he disdained to take the literacy exam.[16] Reading the "Hundred Authors" was part of the family literary tradition, and he was also able to compose poetry before he was ten.[7] The young Li also engaged in other activities, such as taming wild birds and fencing.[16] His other activities included riding, hunting, traveling, and aiding the poor or oppressed by means of both money and arms.[7] Eventually, the young Li seems to have become quite skilled in swordsmanship; as this autobiographical quote by Li himself both testifies to and also helps to illustrate the wild life that he led in the Sichuan of his youth:

When I was fifteen, I was fond of sword play, and with that art I challenged quite a few great men.[17]

Before he was twenty, Li had fought and killed several men, apparently for reasons of chivalry, in accordance with the knight-errant tradition (youxia).[16]

In 720, he was interviewed by Governor Su Ting, who considered him a genius. Though he expressed the wish to become an official, he never took the civil service examination.

On the way to Chang'an

Leaving Sichuan

In his mid-twenties, about 725, Li Bai left Sichuan, sailing down the Yangzi River through Dongting Lake to Nanjing, beginning his days of wandering. He then went back up-river, to Yunmeng, in what is now Hubei, where his marriage to the granddaughter of a retired prime minister, Xu Yushi, seems to have formed but a brief interlude.[18] During the first year of his trip, he met celebrities and gave away much of his wealth to needy friends.

In 730, Li Bai stayed at Zhongnan Mountain near the capital Chang'an (Xi'an), and tried but failed to secure a position. He sailed down the Yellow River, stopped by Luoyang, and visited Taiyuan before going home. In 735, Li Bai was in Shanxi, where he intervened in a court martial against Guo Ziyi, who was later, after becoming one of the top Tang generals, to repay the favour during the An Shi disturbances.[13] By perhaps 740, he had moved to Shandong. It was in Shandong at this time that he became one of the group known as the "Six Idlers of the Bamboo Brook", an informal group dedicated to literature and wine.[13] He wandered about the area of Zhejiang and Jiangsu, eventually making friends with a famous Daoist priest, Wu Yun.[13] In 742, Wu Yun was summoned by the Emperor to attend the imperial court, where his praise of Li Bai was great.[13]

At Chang'an

Wu Yun's praise of Li Bai led Emperor Xuanzong (born Li Longji and also known as Emperor Minghuang) to summon Li to the court in Chang'an. Li's personality fascinated the aristocrats and common people alike, including another Taoist (and poet), He Zhizhang, who bestowed upon him the nickname the "Immortal Exiled from Heaven".[13] Indeed, after an initial audience, where Li Bai was questioned about his political views, the Emperor was so impressed that he held a big banquet in his honor. At this banquet, the Emperor was said to show his favor, even to the extent of personally seasoning his soup for him.[13][19]

Emperor Xuanzong employed him as a translator, as Li Bai knew at least one non-Chinese language.[13] Ming Huang eventually gave him a post at the Hanlin Academy, which served to provide scholarly expertise and poetry for the Emperor.

When the emperor ordered Li Bai to the palace, he was often drunk, but quite capable of performing on the spot.

Li Bai wrote several poems about the Emperor's beautiful and beloved Yang Guifei, the favorite royal consort.[20] A story, probably apocryphal, circulates about Li Bai during this period. Once, while drunk, Li Bai had gotten his boots muddy, and Gao Lishi, the most politically powerful eunuch in the palace, was asked to assist in the removal of these, in front of the Emperor. Gao took offense at being asked to perform this menial service, and later managed to persuade Yang Guifei to take offense at Li's poems concerning her.[20] At the persuasion of Yang Guifei and Gao Lishi, Xuanzong reluctantly, but politely, and with large gifts of gold and silver, sent Li Bai away from the royal court.[21] After leaving the court, Li Bai formally became a Taoist, making a home in Shandong, but wandering far and wide for the next ten some years, writing poems.[21] Li Bai lived and wrote poems at Bishan (or Bi Mountain (碧山), today Baizhao Mountain (白兆山)) in Yandian, Hubei. Bi Mountain (碧山) in the poem Question and Answer Amongst the Mountains (山中问答 Shanzhong Wenda) refers to this mountain.[22]

Meeting Du Fu

He met Du Fu in the autumn of 744, when they shared a single room and various activities together, such as traveling, hunting, wine, and poetry, thus established a close and lasting friendship.[23] They met again the following year. These were the only occasions on which they met, in person, although they continued to maintain a relationship through poetry. This is reflected in the dozen or so poems by Du Fu to or about Li Bai which survive, and the one from Li Bai directed toward Du Fu which remains.

War and exile

At the end of 755, the disorders instigated by the rebel general An Lushan burst across the land. The Emperor eventually fled to Sichuan and abdicated. During the confusion, the Crown Prince opportunely declared himself Emperor and head of the government. The An Shi disturbances continued (as they were later called, since they lasted beyond the death of their instigator, carried on by Shi Siming and others). Li Bai became a staff adviser to Prince Yong, one of Ming Huang's (Emperor Xuanzong's) sons, who was far from the top of the primogeniture list, yet named to share the imperial power as a general after Xuanzong had abdicated, in 756.

However, even before the empire's external enemies were defeated, the two brothers fell to fighting each other with their armies. Upon the defeat of the Prince's forces by his brother the new emperor in 757, Li Bai escaped, but was later captured, imprisoned in Jiujiang, and sentenced to death. The famous and powerful army general Guo Ziyi and others intervened; Guo Ziyi was the very person whom Li Bai had saved from court martial a couple of decades before.[21] His wife, the lady Zong, and others (such as Song Ruosi) wrote petitions for clemency.[24] Upon General Guo Ziyi's offering to exchange his official rank for Li Bai's life, Li Bai's death sentence was commuted to exile: he was consigned to Yelang.[21] Yelang (in what is now Guizhou) was in the remote extreme southwestern part of the empire, and was considered to be outside the main sphere of Chinese civilization and culture. Li Bai headed toward Yelang with little sign of hurry, stopping for prolonged social visits (sometimes for months), and writing poetry along the way, leaving detailed descriptions of his journey for posterity. Notice of an imperial pardon recalling Li Bai reached him before he even got near Yelang.[21] He had only gotten as far as Wushan, when news of his pardon caught up with him in 759.[24]

Return and other travels

When Li received the news of his imperial reprieve, he returned down the river to Jiangxi, passing on the way through Baidicheng, in Kuizhou Prefecture, still engaging in the pleasures of food, wine, good company, and writing poetry; his poem "Departing from Baidi in the Morning" records this stage of his travels, as well as poetically mocking his enemies and detractors, implied in his inclusion of imagery of monkeys. Although Li did not cease his wandering lifestyle, he then generally confined his travels to Nanjing and the two Anhui cities of Xuancheng and Li Yang (in modern Zhao County).[21] His poems of this time include nature poems and poems of socio-political protest.[23] Eventually, in 762, Li's relative Li Yangbing became magistrate of Dangtu, and Li Bai went to stay with him there.[21] In the meantime, Suzong and Xuanzong both died within a short period of time, and China had a new emperor. Also, China was involved in renewed efforts to suppress further military disorders stemming from the Anshi rebellions, and Li volunteered to serve on the general staff of the Chinese commander Li Guangbi. However, at age 61, Li became critically ill, and his health would not allow him to fulfill this plan.[25]

Death

The new Emperor Daizong named Li Bai the Registrar of the Left Commandant's office in 762. However, by the time that the imperial edict arrived in Dangtu, Anhui, Li Bai was already dead.

There is a long and sometimes fanciful tradition regarding his death, from uncertain Chinese sources, that Li Bai drowned after falling from his boat one day he had gotten very drunk as he tried to embrace the reflection of the moon in the Yangtze River, something later believed by Herbert Giles.[21] However, the actual cause appears to have been natural enough, although perhaps related to his hard-living lifestyle. Nevertheless, the legend has a place in Chinese culture.[26]

A memorial of Li Bai lies just west of Ma'anshan.

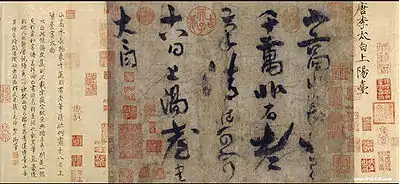

Calligraphy

Li Bai was also a skilled calligrapher, though there is only one surviving piece of his calligraphy work in his own handwriting that exists today.[27] The piece is titled Shàng yáng tái (Going Up To Sun Terrace), a 38.1 by 28.5 centimetres (15.0 in × 11.2 in) long scroll (with later addition of a title written by Emperor Huizong of Song and a postscript added by Qianlong Emperor himself); the calligraphy is housed in the Palace Museum in Beijing, China.[28]

Surviving texts and editing

Even Li Bai and Du Fu, the two most famous and most comprehensively edited Tang poets, were affected by the destruction of the imperial Tang libraries and the loss of many private collections in the periods of turmoil (An Lushan Rebellion and Huang Chao Rebellion). Although many of Li Bai's poems have survived, even more were lost and there is difficulty regarding variant texts. One of the earliest endeavors at editing Li Bai's work was by his relative Li Yangbing, the magistrate of Dangtu, with whom he stayed in his final years and to whom he entrusted his manuscripts. However, the most reliable texts are not necessarily in the earliest editions. Song dynasty scholars produced various editions of his poetry, but it was not until the Qing dynasty that such collections as the Quan Tangshi (Complete Tang Poems) made the most comprehensive studies of the then surviving texts.[29]

Themes

Critics have focused on Li Bai's strong sense of the continuity of poetic tradition, his glorification of alcoholic beverages (and, indeed, frank celebration of drunkenness), his use of persona, the fantastic extremes of some of his imagery, his mastery of formal poetic rules—and his ability to combine all of these with a seemingly effortless virtuosity to produce inimitable poetry. Other themes in Li's poetry, noted especially in the 20th century, are sympathy for the common folk and antipathy towards needless wars (even when conducted by the emperor himself).[30]

Poetic tradition

Li Bai had a strong sense of himself as being part of a poetic tradition. The "genius" of Li Bai, says one recent account, "lies at once in his total command of the literary tradition before him and his ingenuity in bending (without breaking) it to discover a uniquely personal idiom..."[31] Burton Watson, comparing him to Du Fu, says Li's poetry, "is essentially backward-looking, that it represents more a revival and fulfillment of past promises and glory than a foray into the future."[32] Watson adds, as evidence, that of all the poems attributed to Li Bai, about one sixth are in the form of yuefu, or, in other words, reworked lyrics from traditional folk ballads.[33] As further evidence, Watson cites the existence of a fifty-nine poem collection by Li Bai entitled Gu Feng, or In the Old Manner, which is, in part, tribute to the poetry of the Han and Wei dynasties.[34] His admiration for certain particular poets is also shown through specific allusions, for example to Qu Yuan or Tao Yuanming, and occasionally by name, for example Du Fu.

A more general appreciation for history is shown on the part of Li Bai in his poems of the huaigu genre,[35] or meditations on the past, wherein following "one of the perennial themes of Chinese poetry", "the poet contemplates the ruins of past glory".[36]

Rapt with wine and moon

John C. H. Wu observed that "while some may have drunk more wine than Li [Bai], no-one has written more poems about wine."[37] Classical Chinese poets were often associated with drinking wine, and Li Bai was part of the group of Chinese scholars in Chang'an his fellow poet Du Fu called the "Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup." The Chinese generally did not find the moderate use of alcohol to be immoral or unhealthy. James J. Y Liu comments that zui in poetry "does not mean quite the same thing as 'drunk', 'intoxicated', or 'inebriated', but rather means being mentally carried away from one's normal preoccupations ..." Liu translates zui as "rapt with wine".[38] The "Eight Immortals", however, drank to an unusual degree, though they still were viewed as pleasant eccentrics.[39] Burton Watson concluded that "[n]early all Chinese poets celebrate the joys of wine, but none so tirelessly and with such a note of genuine conviction as Li [Bai]".[40]

The following two poems, "Rising Drunk on a Spring Day, Telling My Intent" and "Drinking Alone by Moonlight", are among Li Bai's most famous and demonstrate different aspects of his use of wine and drunkenness.

We are lodged in this world as in a great dream;

Then why cause our lives so much stress?

This is my reason to spend the day drunk

And collapse, sprawled against the front pillar.

When I wake, I peer out in the yard

Where a bird is singing among the flowers.

Now tell me, what season is this?—

The spring breeze speaks with orioles warbling.

I am so touched that I almost sigh,

I turn to the wine, pour myself more,

Then sing wildly, waiting for the moon,

When the tune is done, I no longer care.

處世若大夢,

胡爲勞其生.

所以終日醉,

頹然臥前楹.

覺來盼庭前,

一鳥花間鳴.

借問此何時,

春風語流鶯.

感之欲嘆息,

對酒還自傾.

浩歌待明月,

曲盡已忘情.

— "Rising Drunk on a Spring Day, Telling My Intent" (Chūnrì

zuìqǐ yánzhì 春日醉起言志), translated by Stephen Owen[41]

Here among flowers one flask of wine,

With no close friends, I pour it alone.

I lift cup to bright moon, beg its company,

Then facing my shadow, we become three.

The moon has never known how to drink;

My shadow does nothing but follow me.

But with moon and shadow as companions the while,

This joy I find must catch spring while it's here.

I sing, and the moon just lingers on;

I dance, and my shadow flails wildly.

When still sober we share friendship and pleasure,

Then, utterly drunk, each goes his own way—

Let us join to roam beyond human cares

And plan to meet far in the river of stars.

花間一壺酒。

獨酌無相親。

舉杯邀明月。

對影成三人。

月既不解飲。

影徒隨我身。

暫伴月將影。

行樂須及春。

我歌月徘徊。

我舞影零亂。

醒時同交歡。

醉後各分散。

永結無情遊。

相期邈雲漢。

— "Drinking Alone by Moonlight" (Yuèxià

dúzhuó 月下獨酌), translated

by Stephen Owen[42]

Fantastic imagery

An important characteristic of Li Bai's poetry "is the fantasy and note of childlike wonder and playfulness that pervade so much of it".[34] Burton Watson attributes this to a fascination with the Taoist priest, Taoist recluses who practiced alchemy and austerities in the mountains, in the aim of becoming xian, or immortal beings.[34] There is a strong element of Taoism in his works, both in the sentiments they express and in their spontaneous tone, and "many of his poems deal with mountains, often descriptions of ascents that midway modulate into journeys of the imagination, passing from actual mountain scenery to visions of nature deities, immortals, and 'jade maidens' of Taoist lore".[34] Watson sees this as another affirmation of Li Bai's affinity with the past, and a continuity with the traditions of the Chuci and the early fu.[40] Watson finds this "element of fantasy" to be behind Li Bai's use of hyperbole and the "playful personifications" of mountains and celestial objects.[40]

Nostalgia

The critic James J.Y. Liu notes "Chinese poets seem to be perpetually bewailing their exile and longing to return home. This may seem sentimental to Western readers, but one should remember the vastness of China, the difficulties of communication... the sharp contrast between the highly cultured life in the main cities and the harsh conditions in the remoter regions of the country, and the importance of family..." It is hardly surprising, he concludes, that nostalgia should have become a "constant, and hence conventional, theme in Chinese poetry."[43]

Liu gives as a prime example Li's poem "A Quiet Night Thought" (also translated as "Contemplating Moonlight"), which is often learned by schoolchildren in China. In a mere 20 words, the poem uses the vivid moonlight and frost imagery to convey the feeling of homesickness. This translation is by Yang Xianyi and Dai Naidie:[44]

Thoughts in the Silent Night (Jìngyè Sī 静夜思)

床前明月光, Beside my bed a pool of light—

疑是地上霜, Is it hoarfrost on the ground?

舉頭望明月, I lift my eyes and see the moon,

低頭思故鄉。 I lower my face and think of home.

Use of persona

Li Bai also wrote a number of poems from various viewpoints, including the personae of women. For example, he wrote several poems in the Zi Ye, or "Lady Midnight" style, as well as Han folk-ballad style poems.

Technical virtuosity

Li Bai is well known for the technical virtuosity of his poetry and the mastery of his verses.[32] In terms of poetic form, "critics generally agree that Li [Bai] produced no significant innovations ... In theme and content also, his poetry is notable less for the new elements it introduces than for the skill with which he brightens the old ones."[32]

Burton Watson comments on Li Bai's famous poem, which he translates "Bring the Wine": "like so much of Li [Bai]'s work, it has a grace and effortless dignity that somehow make it more compelling than earlier treatment of the same."[45]

Li Bai's yuefu poems have been called the greatest of all time by Ming-dynasty scholar and writer Hu Yinglin.[46]

Li Bai especially excelled in the Gushi form, or "old style" poems, a type of poetry allowing a great deal of freedom in terms of the form and content of the work. An example is his poem "蜀道難", translated by Witter Bynner as "Hard Roads in Shu". Shu is a poetic term for Sichuan, the destination of refuge that Emperor Xuanzong considered fleeing to escape the approaching forces of the rebel General An Lushan. Watson comments that, this poem, "employs lines that range in length from four to eleven characters, the form of the lines suggesting by their irregularity the jagged peaks and bumpy mountain roads of Sichuan depicted in the poem."[32]

Li Bai was also noted as a master of the jueju, or cut-verse.[47] Ming-dynasty poet Li Pan Long thought Li Bai was the greatest jueju master of the Tang dynasty.[48]

Li Bai was noted for his mastery of the lüshi, or "regulated verse", the formally most demanding verse form of the times. Watson notes, however, that his poem "Seeing a Friend Off" was "unusual in that it violates the rule that the two middle couplets ... must observe verbal parallelism", adding that Chinese critics excused this kind of violation in the case of a genius like Li.[49]

Influence

In the East

Li Bai's poetry was immensely influential in his own time, as well as for subsequent generations in China. From early on, he was paired with Du Fu. The recent scholar Paula Varsano observes that "in the literary imagination they were, and remain, the two greatest poets of the Tang—or even of China". Yet she notes the persistence of "what we can rightly call the 'Li-Du debate', the terms of which became so deeply ingrained in the critical discourse surrounding these two poets that almost any characterization of the one implicitly critiqued the other".[50] Li's influence has also been demonstrated in the immediate geographical area of Chinese cultural influence, being known as Ri Haku in Japan. This influence continues even today. Examples range from poetry to painting and to literature.

In his own lifetime, during his many wanderings and while he was attending court in Chang'an, he met and parted from various contemporary poets. These meetings and separations were typical occasions for versification in the tradition of the literate Chinese of the time, a prime example being his relationship with Du Fu.

After his lifetime, his influence continued to grow. Some four centuries later, during the Song dynasty, for example, just in the case of his poem that is sometimes translated "Drinking Alone Beneath the Moon", the poet Yang Wanli wrote a whole poem alluding to it (and to two other Li Bai poems), in the same gushi, or old-style poetry form.[51]

In the 20th century, Li Bai even influenced the poetry of Mao Zedong.

In China, his poem "Quiet Night Thoughts", reflecting a nostalgia of a traveller away from home,[52] has been widely "memorized by school children and quoted by adults".[53]

He is sometimes worshipped as an immortal in Chinese folk religion and is also considered a divinity in Vietnam Cao Dai religion.

In the West

Swiss composer Volkmar Andreae set eight poems as Li-Tai-Pe: Eight Chinese songs for tenor and orchestra, op. 37. American composer Harry Partch, based his Seventeen Lyrics by Li Po for intoning voice and Adapted Viola (an instrument of Partch's own invention) on texts in The Works of Li Po, the Chinese Poet translated by Shigeyoshi Obata.[54] In Brazil, the songwriter Beto Furquim included a musical setting of the poem "Jing Ye Si" in his album "Muito Prazer".[55]

Ezra Pound

Li Bai is influential in the West partly due to Ezra Pound's versions of some of his poems in the collection Cathay,[56] (Pound transliterating his name according to the Japanese manner as "Rihaku"). Li Bai's interactions with nature, friendship, his love of wine and his acute observations of life inform his more popular poems. Some, like Changgan xing (translated by Ezra Pound as "The River Merchant's Wife: A Letter"),[56] record the hardships or emotions of common people. An example of the liberal, but poetically influential, translations, or adaptations, of Japanese versions of his poems made, largely based on the work of Ernest Fenollosa and professors Mori and Ariga.[56]

Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler integrated four of Li Bai's works into his symphonic song cycle Das Lied von der Erde. These were derived from free German translations by Hans Bethge, published in an anthology called Die chinesische Flöte (The Chinese Flute),[57] Bethge based his versions on the collection Chinesische Lyrik by Hans Heilmann (1905). Heilmann worked from pioneering 19th-century translations into French: three by the Marquis d'Hervey-Saint-Denys and one (only distantly related to the Chinese) by Judith Gautier. Mahler freely changed Bethge's text.

Reference in Beat Generation

Li Bai's poetry can be seen as being an influence to Beat Generation writer Gary Snyder during Snyder's years of studying Asian Culture and Zen. Li Bai's style of descriptive writing assisted in the diversity within the Beat writing style.[58][59]

Translation

Li Bai's poetry was introduced to Europe by Jean Joseph Marie Amiot, a Jesuit missionary in Beijing, in his Portraits des Célèbres Chinois, published in the series Mémoires concernant l'histoire, les sciences, les arts, les mœurs, les usages, &c. des Chinois, par les missionnaires de Pekin. (1776–1797).[60] Further translations into French were published by Marquis d'Hervey de Saint-Denys in his 1862 Poésies de l'Époque des Thang.[61]

Joseph Edkins read a paper, "On Li Tai-po", to the Peking Oriental Society in 1888, which was subsequently published in that society's journal.[62] The early sinologist Herbert Allen Giles included translations of Li Bai in his 1898 publication Chinese Poetry in English Verse, and again in his History of Chinese Literature (1901).[63] The third early translator into English was L. Cranmer-Byng (1872–1945). His Lute of Jade: Being Selections from the Classical Poets of China (1909) and A Feast of Lanterns (1916) both featured Li's poetry.

Renditions of Li Bai's poetry into modernist English poetry were influential through Ezra Pound in Cathay (1915) and Amy Lowell in Fir-Flower Tablets (1921). Neither worked directly from the Chinese: Pound relied on more or less literal, word for word, though not terribly accurate, translations of Ernest Fenollosa and what Pound called the "decipherings" of professors Mori and Ariga; Lowell on those of Florence Ayscough. Witter Bynner with the help of Kiang Kang-hu included several of Li's poems in The Jade Mountain (1939). Although Li was not his preferred poet, Arthur Waley translated a few of his poems into English for the Asiatic Review, and included them in his More Translations from the Chinese. Shigeyoshi Obata, in his 1922 The Works of Li Po, claimed he had made "the first attempt ever made to deal with any single Chinese poet exclusively in one book for the purpose of introducing him to the English-speaking world.[60] A translation of Li Bai's poem Green Moss by poet William Carlos Williams was sent as a letter to Chinese American poet David Rafael Wang where Williams was seen as having a similar tone as Pound.[64]

Li Bai became a favorite among translators for his straightforward and seemingly simple style. Later translations are too numerous to discuss here, but an extensive selection of Li's poems, translated by various translators, is included in John Minford and Joseph S. M. Lau, Classical Chinese Literature (2000)[65]

In popular culture

- Portrayed by Wong Wai-leung in the 2000 television series The Legend of Lady Yang

- An actor playing Li Bai narrates the Wonders of China and Reflections of China films at the China Pavilion at Epcot

- Li Bai's poem 'Hard Roads in Shu' is sung by a Chinese singer AnAn in a Liu Bei trailer for a game Total War: Three Kingdoms[66]

- He appears as a "great writer" in the game Civilization VI[67]

See also

- Chinese martial arts

- Ci (poetry)

- Classical Chinese poetry

- Classical Chinese poetry forms

- Guqin

- Jiangyou

- Modernist poetry in English

- Monkeys in Chinese culture#Literature

- Poetry of Mao Zedong

- Iranians in China

- Shi (poetry)

- Simians (Chinese poetry)#In Baidicheng, back from the way to exile

- Tang poetry

- List of Three Hundred Tang Poems poets

- Tomb of Li Bai

- Xu Yushi

- A Quiet Night Thought

- Ode to Gallantry

Notes

- The New Book of Tang 文宗時,詔以白歌詩、裴旻劍舞、張旭草書為「三絕」

- 河岳英靈集

- Sun, Zhu (1763). "300 Tang Poems". Bookshop. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Barnstone, Tony and Chou Ping (2010). The Anchor Book of Chinese Poetry: From Ancient to Contemporary, The Full 3000-Year Tradition. Random House. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-307-48147-4.

- Obata, Part III

- Beckwith, 127

- Sun, 20

- Obata, 8

- Wu, 57–58

- Elling Eide, "On Li Po", Perspectives on the T'ang (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1973), 388.

- Eide (1973), 389.

- Sun, 1982, 20 and 21

- Wu, 59

- "Li Bai, Why I live in the Green Mountains". 7 June 2020.

- Sun, 24, 25, and 166

- Wu, 58

- Wu, 58. Translation by Wu. Note that by East Asian age reckoning, this would be fourteen rather than fifteen years old.

- Wu, 58–59

- Obata, 201

- Wu, 60

- Wu, 61

- "中国安陆网–乡镇 烟店镇简介" [Anlu, China Website-Township-Level Divisions Yandian Town Overview]. 中国安陆网 (in Chinese). 中共安陆市委 安陆市人民政府 中共安陆市委宣传部 安陆市互联网信息中心. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

烟店镇人文底蕴深厚,诗仙李白"酒隐安陆,蹉跎十年",谪居于此。"问余何意栖碧山,笑而不答心自闲。桃花流水窅然去,别有天地非人间。"这首《山中问答》中的碧山就是位于烟店镇的白兆山,李白在白兆山居住期间,

- Sun, 24 and 25

- Sun, 26 and 27

- Sun, 26–28

- "黃大仙靈簽11至20簽新解". Archived from the original on 20 July 2015.

- Belbin, Charles and T.R. Wang. "Going Up To Sun Terrace by Li Bai: An Explication, Translation & History". Flashpoint Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

It is now housed in the Palace Museum in Beijing. Scholars commonly acknowledge it as authentic and the only known surviving piece of calligraphy by Li Bai.

- Arts of Asia: Volume 30 (2000). Selected paintings and calligraphy acquired by the Palace Museum in the last fifty years. Arts of Asia. p. 56.

- Paul Kroll, "Poetry of the T’ang Dynasty," in Victor H. Mair, ed., The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001). ISBN 0-231-10984-9), pp. 278–282, section "The Sources and Their Limitations" describes this history.

- Sun, 28–35

- Paul Kroll, "Poetry of the T’ang Dynasty," in Victor H. Mair, ed., The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001; ISBN 0-231-10984-9), p. 296.

- Watson, 141

- Watson, 141–142

- Watson, 142

- Watson, 145

- Watson, 88

- Wu, 66

- James J.Y. Liu. The Art of Chinese Poetry. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962; ISBN 0-226-48686-9), p. 59.

- William Hung. Tu Fu: China's Greatest Poet. (Cambridge,: Harvard University Press, 1952), p 22.

- Watson, 143

- Owen (1996), p. 404.

- Owen (1996), pp. 403–04.

- James J.Y. Liu. The Art of Chinese Poetry. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962; ISBN 0-226-48686-9) p. 55.

- "Top 10 most influential Chinese classical poems". chinawhisper.com. China whisper. 13 January 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- Watson, 144

- Shisou(Thickets of Poetic Criticism)

- Watson, 146

- Selections of Tang Poetry

- Watson, 147

- Varsano (2014).

- Frankel, 22

- How to read Chinese poetry: a guided anthology By Zong-qi Cai p. 210. Columbia University Press

- Speaking of Chinese By Raymond Chang, Margaret Scrogin Chang p. 176 WW Norton & Company

- Obata, Shigeyoshi (1923). The Works of Li Po, the Chinese Poet (J.M. Dent & Co, ). ASIN B000KL7LXI

- (2008, ISRC BR-OQQ-08-00002)

- Pound, Ezra (1915). Cathay (Elkin Mathews, London). ASIN B00085NWJI.

- Bethge, Hans (2001). Die Chinesische Flöte (YinYang Media Verlag, Kelkheim, Germany). ISBN 978-3-9806799-5-4. Re-issue of the 1907 edition (Insel Verlag, Leipzig).

- "Snyder".

- Beat Generation

- Obata, v

- D'Hervey de Saint-Denys (1862). Poésies de l'Époque des Thang (Amyot, Paris). See Minford, John and Lau, Joseph S. M. (2000). Classic Chinese Literature (Columbia University Press) ISBN 978-0-231-09676-8.

- Obata, p. v.

- Obata, v–vi

- "WCW's voice near the end: Green moss | Jacket2".

- Ch 19 "Li Bo (701–762): The Banished Immortal" Introduction by Burton Watson; translations by Elling Eide; Ezra Pound; Arthur Cooper, David Young; five poems in multiple translations, in John Minford and Joseph S. M. Lau, eds., Classical Chinese Literature (New York; Hong Kong: Columbia University Press; The Chinese University Press, 2000), pp. 721–763.

- Total War: THREE KINGDOMS - Liu Bei Launch Trailer, retrieved 28 August 2022

- Woodrick, Sam (10 June 2020). "Civilization 6: How to Use Great Writers". Game Rant. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

References

Translations into English

- Cooper, Arthur (1973). Li Po and Tu Fu: Poems Selected and Translated with an Introduction and Notes (Penguin Classics, 1973). ISBN 978-0-14-044272-4.

- Hinton, David (2008). Classical Chinese Poetry: An Anthology. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-10536-7, 978-0-374-10536-5

- Hinton, David (1998). The Selected Poems of Li Po (Anvil Press Poetry, 1998). ISBN 978-0-85646-291-7

- Holyoak, Keith (translator) (2007). Facing the Moon: Poems of Li Bai and Du Fu. (Durham, NH: Oyster River Press). ISBN 978-1-882291-04-5

- Obata, Shigeyoshi (1922). The Works of Li Po, the Chinese Poet. (New York: Dutton). Reprinted: New York: Paragon, 1965. Free E-Book.

- Owen, Stephen (1996). An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-97106-6.

- Pound, Ezra (1915). Cathay (Elkin Mathews, London). ASIN B00085NWJI

- Smith, Kidder and Zhai, Mike (2021). Li Bo Unkempt. Punctum Press. ISBN 1953035418

- Stimson, Hugh M. (1976). Fifty-five T'ang Poems. Far Eastern Publications: Yale University. ISBN 0-88710-026-0

- Seth, Vikram (translator) (1992). Three Chinese Poets: Translations of Poems by Wang Wei, Li Bai, and Du Fu. (London: Faber & Faber). ISBN 0-571-16653-9

- Weinberger, Eliot. The New Directions Anthology of Classical Chinese Poetry. (New York: New Directions, 2004). ISBN 0-8112-1605-5. Introduction, with translations by William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound, Kenneth Rexroth, Gary Snyder, and David Hinton.

- Watson, Burton (1971). Chinese Lyricism: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03464-4

- Mao, Xian (2013). Children's Version of 60 Classical Chinese Poems. eBook: Kindle Direct Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4685-5904-0.

- Sun, Yu [孫瑜], translation, introduction, and commentary (1982). Li Po-A New Translation 李白詩新譯. Hong Kong: The Commercial Press, ISBN 962-07-1025-8

Background and criticism

- Edkins, Joseph (1888). "Li Tai-po as a Poet", The China Review, Vol. 17 No. 1 (1888 Jul) . Retrieved from , 19 January 2011.

- Eide, Elling (1973). "On Li Po", in Perspectives on the T'ang. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 367–403.

- Frankel, Hans H. (1978). The Flowering Plum and the Palace Lady. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press) ISBN 0-300-02242-5.

- Kroll, Paul (2001). "Poetry of the T’ang Dynasty," in Victor H. Mair. ed., The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001). ISBN 0-231-10984-9, pp. 274–313.

- Stephen Owen 'Li Po: a new concept of genius," in Stephen Owen. The Great Age of Chinese Poetry : The High T'ang. (New Haven Conn.: Yale University Press, 1981). ISBN 978-0-300-02367-1.

- Varsano, Paula M. (2003). Tracking the Banished Immortal: The Poetry of Li Bo and its Critical Reception (University of Hawai'i Press, 2003). ISBN 978-0-8248-2573-7,

- —— (2014). "Li Bai and Du Fu". Oxford Bibliographies Online. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199920082-0106. ISBN 9780199920082.. Lists and evaluates scholarship and translations.

- Waley, Arthur (1950). The Poetry and Career of Li Po (New York: MacMillan, 1950). ASIN B0006ASTS4

- Wu, John C.H. (1972). The Four Seasons of Tang Poetry. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle. ISBN 978-0-8048-0197-3

Further reading

- Hsieh, Chinghsuan Lily. "Chinese Poetry of Li Po Set by Four Twentieth Century British Composers: Bantock, Warlock, Bliss and Lambert" (Archive) (PhD thesis). Ohio State University, 2004.

- Li Bo Unkempt / Kidder Smith, Mike Zhai // Punctum Books, 2021. — ISBN 9781953035417, 9781953035424; doi:10.21983/P3.0322.1.00.

External links

Online translations (some with original Chinese, pronunciation, and literal translation):

- Poems by Li Bai at Poems Found in Translation

- Li Bai: Poems Extensive collection of Li Bai poems in English

- 20 Li Bai poems, in Chinese using simplified and traditional characters and pinyin, with literal and literary English translations by Mark Alexander.

- 34 Li Bai poems, in Chinese with English translation by Witter Bynner, from the Three Hundred Tang Poems anthology.

- Complete text of Cathay, the Ezra Pound/Ernest Fenollosa translations of poems principally by Li Po (J., Rihaku)

- Profile Variety of translations of Li Bai's poetry by a range of translators, along with photographs of geographical sites relevant to his life.

- At Project Gutenberg from More Translations From The Chinese by Arthur Waley, 1919 (includes six titles of poems by Li Po).

- The works of Li Po, the Chinese poet, translated by Shigeyoshi Obata, Obata's 1922 translation.

- Li Po's poems at PoemHunter.com site

- Works by Li Bai at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- John Thompson on Li Bai and the qin musical instrument