Li Wenliang

Li Wenliang (Chinese: 李文亮; 12 October 1986 – 7 February 2020) was a Chinese ophthalmologist who warned his colleagues about early COVID-19 infections in Wuhan.[2] On 30 December 2019, Wuhan CDC issued emergency warnings to local hospitals about a number of mysterious "pneumonia" cases discovered in the city in the previous week.[3] On the same day, Li, who worked at the Central Hospital of Wuhan, received an internal diagnostic report of a suspected severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) patient from other doctors which he in turn shared with his Wuhan University alumni through a WeChat group. He was dubbed a whistleblower when that shared report later circulated publicly despite his requesting confidentiality from those with whom he shared the information.[4][5] Rumors of a deadly SARS outbreak subsequently spread on Chinese social media platforms; Wuhan police summoned and admonished him and seven other doctors on 3 January for "making false comments on the Internet about unconfirmed SARS outbreak."[4][6]

Li Wenliang | |

|---|---|

李文亮 | |

| |

| Born | 12 October 1986 Beizhen, Jinzhou, Liaoning, China |

| Died | 7 February 2020 (aged 33) Wuhan, Hubei, China |

| Cause of death | COVID-19 |

| Alma mater | Wuhan University (MMed) |

| Occupation | Ophthalmologist |

| Years active | 2011–2020 |

| Known for | Warning people about COVID-19 before it became a pandemic |

| Spouse | Fu Xuejie[1](付雪洁) |

| Children | 2 |

| Li Wenliang | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 李文亮 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The outbreak was later confirmed not to be SARS, but rather a new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. Li returned to work and later contracted COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, from a patient who was not known to be infected. He died from the disease on 7 February 2020, at age 33.[7][8] A subsequent Chinese official inquiry exonerated him; Wuhan police formally apologized to his family and revoked his admonishment on 19 March.[9][10][11][12] In April 2020, Li was posthumously awarded the May Fourth Medal by the government.[13] By early June 2020, five more doctors from the Wuhan hospital had died from COVID-19.[14]

Early life

Li Wenliang was born on 12 October 1986 in a Manchu family[15] in Beizhen, Jinzhou, Liaoning.[16] His parents were former state enterprise workers and both lost their jobs in the 'wave of laid-offs' in the 1990s.[17] He attended Beizhen High School (北镇市高级中学) and graduated in 2004 with an excellent academic record. He attended Wuhan University School of Medicine as a clinical medicine student in a seven-year combined bachelor's and master's degree program. He joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in his second year.[18] His mentor praised him as a diligent and honest student. His college classmates said he was a basketball fan.[19][20]

Career

After graduation in 2011, Li worked at the Xiamen Eye Center of Xiamen University for three years.[21] In 2014, Li became an ophthalmologist at Wuhan Central Hospital in Wuhan.[4]

Role in COVID-19 pandemic

on 30 December 2019

(CST 17:43)

- Li: There are 7 confirmed cases of SARS at Huanan Seafood Market.

- Li: (Picture of diagnosis report)

- Li: (Video of CT scan results)

- Li: They are being isolated in the emergency department of our hospital's Houhu Hospital District.

(CST 18:42)

- Someone: Be careful, or else our chat group might be dismissed.

- Li: The latest news is, it has been confirmed that they are coronavirus infections, but the exact virus is being subtyped.

- Li: Don't circulate the information outside of this group, tell your family and loved ones to take precautions.

- Li: In 1937, coronaviruses were first isolated from chicken...

Source: screenshots in The Beijing News report[22]

In late December, doctors in Wuhan were puzzled by many "pneumonia" cases of unknown cause. On 30 December 2019, the Wuhan CDC sent out an internal memo to all Wuhan hospitals to be alerted and started an investigation into the exact cause of the pneumonia. The alert and subsequent news reports were immediately published on ProMED (a program of the International Society for Infectious Diseases).[23] On the same day, Li saw a patient's report which showed a positive result with a high confidence level for SARS coronavirus tests. The report had originated from Ai Fen, director of the emergency department at Wuhan Central hospital, who became alarmed after receiving laboratory results of a patient whom she had examined who exhibited symptoms akin to influenza resistant to conventional treatment methods. The report contained the phrase "SARS coronavirus." Ai had circled the word "SARS" and sent it to a doctor at another hospital in Wuhan. From there it spread throughout medical circles in the city, where it reached Li.[24] At 17:43, he wrote in a private WeChat group of his medical school classmates: "7 confirmed cases of SARS were reported [to hospital] from Huanan Seafood Market." He also posted the patient's examination report and CT scan image. At 18:42, he added "the latest news is, it has been confirmed that they are coronavirus infections, but the exact virus strain is being subtyped."[4] Li asked the WeChat group members to inform their families and friends to take protective measures whilst requesting discretion from those he shared the information with; he was upset when the discussion gained a wider audience than he had hoped.[25]

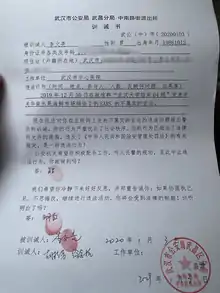

After screenshots of his WeChat messages were shared on Chinese Internet and gained more attention, the supervision department of his hospital summoned him for a talk, blaming him for leaking the information.[4] On 3 January 2020, police from the Wuhan Public Security Bureau investigating the case interrogated Li, issued a formal written warning and censuring him for "publishing untrue statements about seven confirmed SARS cases at the Huanan Seafood Market."[26] He was made to sign a letter of admonition promising not to do it again.[4] The police warned him that any recalcitrant behavior would result in a prosecution.[27]

Li returned to work at the hospital and contracted the virus on 8 January. On 31 January, he published his experience in the police station with the letter of admonition on social media. His post went viral and users questioned why the doctors who gave earlier warnings were silenced by the authorities.[28]

Reaction

The existence of Li's personal blog where he documented his discoveries was reported by the Italian newspaper La Stampa on 1 February.[29] Li later responded that he did not know whether he was one of the so-called "rumor mongers," but that he had been admonished for claiming a SARS outbreak, which at that time was unconfirmed.[30] The police punishment of Li for "rumor mongering" was aired on China Central Television, signaling central government endorsement for the reprimand, according to two reporters for the South China Morning Post.[31]

On 4 February, the Chinese Supreme People's Court said that the eight Wuhan citizens should not have been punished as what they said was not entirely false. It wrote on social media: "It might have been a fortunate thing if the public had believed the 'rumors' then and started to wear masks and carry out sanitization measures, and avoid the wild animal market."

Li told Caixin that he had been worried the hospital would punish him for "spreading rumors," but felt relieved after the top court publicly criticized the police, and said, "I think there should be more than one voice in a healthy society, and I don't approve of using public power for excessive interference."

On December 31, 2019, Yijun Luo, then deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control of the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan, was browsing the Internet when he discovered that an Internet user had posted a warning message from Dr. Wenliang Li about a new SARS-like virus, which alerted him. After researching the message, Luo Yijun considered it highly credible and initiated a series of epidemic prevention procedures, and at a press conference on April 16, 2020, Luo Yijun expressed his gratitude to Dr. Li Wenliang.[33]

Illness and death

COVID-19 infection

On 8 January, Li contracted COVID-19 unwittingly while treating an infected patient at his hospital.[34] The patient suffered from acute angle-closure glaucoma and developed a fever the next day that Li then suspected was coronavirus-related.[28] Li developed a fever and cough two days later which soon became severe.[34] Doctor Yu Chengbo, a Zhejiang medical expert sent to Wuhan, told media that the glaucoma patient whom Li saw on 8 January was a storekeeper at Huanan Seafood Market with a high viral load, which could have exacerbated Li's infection.[35]

On 12 January, Li was admitted to intensive care at Houhu Hospital District, Wuhan Central Hospital,[36] where he was quarantined and treated.[34] He tested positive for the virus on 30 January and formally diagnosed with the virus infection on 1 February.[28] While hospitalized, Li posted a message online vowing to return to the front lines after his recovery.[37]

Death

On 6 February, while Li was on the phone with a friend, he told the friend that his oxygen saturation had dropped to 85%.[36] Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was reportedly used to keep him alive.[38] According to China Newsweek, his heartbeat stopped at 21:30.[38] In social media posts, the Chinese state media reported that Li had died,[39] but the posts were soon deleted.[40] Later, Wuhan Central Hospital released a statement contradicting reports of his death: "In the process of fighting the coronavirus, the eye doctor from our hospital Li Wenliang was unfortunately infected. He is now in critical condition and we are doing our best to rescue him."[41] The hospital formally announced that Li had died at 2:58 a.m. on 7 February 2020.[7][42] During the confusion, more than 17 million people were watching the live stream for updates on his status.[37]

Aftermath

By early June 2020, five other doctors had died from COVID-19 in the Wuhan hospital, now called "whistleblower hospital".[14] Hu Weifeng, a urologist and a coworker of Li, was the sixth doctor of the hospital to die from the virus on 2 June 2020, after four months of hospitalization.[43] The hashtag #WeWantFreedomOfSpeech (Chinese: #我们要言论自由#[44]) gained over 2 million views and over 5,500 posts within 5 hours before it was removed by censors, as were other related hashtags and posts.[45][46][47] Wuhan citizens placed flowers and blew whistles at Wuhan Central Hospital, where Li worked and died, as a tribute to him.[48] On the Internet, people spontaneously launched the activity themed "I blew a whistle for Wuhan tonight," where everyone kept all the lights off in their homes for five minutes, and later blew whistles and waved glitter outside of their windows for five minutes to mourn Li.[49][50] Many people left messages in response to Li's last post on Sina Weibo, some lamenting his death and expressing anger at the authorities. He was also proclaimed an "ordinary hero."[25] The World Health Organization posted on Twitter saying that it was "deeply saddened by the passing of Dr Li Wenliang" and "we all need to celebrate work that he did on #2019nCoV."[51]

Although there was no official apology from the city of Wuhan for reprimanding Li, the Wuhan municipal government and the Health Commission of Hubei made statements of tribute to Li and condolences to his family. Beyond Wuhan, the National Health Commission did likewise.[25] China's highest anti-corruption body, the National Supervisory Commission, has initiated a "comprehensive investigation" into the issues involving Li.[31] Qin Qianhong, a law professor at Wuhan University expressed his concern that, unless properly managed, public anger over Li's death could explode in a similar way as the death of Hu Yaobang.[31][52]

A group of Chinese academics, led by Tang Yiming – head of the school of Chinese classics at Central China Normal University in Wuhan – published an open letter urging the government to both protect free speech and apologize for Li's death. The letter emphasized the right to free speech, ostensibly guaranteed by the Chinese constitution. Tang said that the viral outbreak was a man-made disaster, and that China ought to learn from Li Wenliang. Tang also wrote he felt that senior intellectuals and academics must speak up for the Chinese people and for their own consciences. "We all should reflect on ourselves," he wrote, "and the officials should rue their mistakes even more."[31] The letter alleges that Li Wenliang "is also a victim of speech suppression."[53][54] Jie Qiao, Academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and President of Peking University Third Hospital in Beijing called Li a "whistle-blower dedicating his young life in the front line."[55][56]

On 7 February 2020, Taiwanese author Yan Zeya (顏擇雅) expressed doubt on the Liberty Times about whether Li should be called a whistleblower, citing his lack of general objection to the government and lack of willingness to expose its dark side.[57]

On 9 February 2020, hundreds of people in New York commemorated Li in a tribute at Central Park.[58] The U.S. Senate honored Li by passing a resolution calling for transparency and cooperation from the Government of the People's Republic of China and the Communist Party of China.[59]

Recognition by the Chinese government

In April, Li was officially honored by the Chinese government as a "martyr," which is the highest honor the government can bestow on a citizen who dies serving China.[60] According to the state-run Xinhua News Agency, he was honored together with 13 other "martyrs," mostly physicians, who died from COVID-19.[61] Chinese Internet users have left more than 870,000 comments under Li's last post on social website Sina Weibo since his death.[62]

On 3 March, International Journal of Infectious Diseases published an article, wrote "Dr Li Wenliang's example as an astute clinician should inspire all of us to be vigilant, bold and courageous in reporting unusual clinical presentations."[63] Italian author Francesca Cavallo wrote a children's book titled Dr. Li and the crown-wearing virus, featuring Li's story, to help educate children on COVID-19.[64] Fortune magazine ranked Li as No.1 of the "World's 25 Greatest Leaders: Heroes of the pandemic."[65] On 4 May, Matt Pottinger, deputy national security adviser of US, hailed Li during a speech in Mandarin.[66]

Personal life

When Li began showing symptoms of COVID-19, he booked a hotel room to avoid the possibility of infecting his family, before being hospitalized on 12 January. Despite this precaution, his parents became infected with SARS-CoV-2, but later recovered.[1][37][55]

Li and his wife, Fu Xuejie (付雪洁), had one son, and were expecting their second child at the time of his death. In June 2020, his widow gave birth to a second son.[1][55][67][68][69]

See also

- Ai Fen, an emergency department doctor who shared the image of a diagnostic report of suspected "severe acute respiratory syndrome cases" (indicated by clinical signs and SARS-specific test) with colleagues and former classmates on 30 December 2019. The image of the report reached Li Wenliang and other doctors in the Wuhan medical circles. The SARS-CoV-2 virus isolation was completed on 8 January 2020. Its near complete sequencing was done on the 27 Dec 2019 by scientists at Vision medicals in Guangzhou, with an early analysis of its genome and its relation to other SARS-like viruses performed on the same day. Vision Medicals had already alerted the Pathogen Institute of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences on the 26 Dec 2019, after partial sequencing and initial analysis on that day, and further visited the hospital and the CDC in Wuhan on the 29/30 Dec 2019, on the occasion of which the Pathogen Institute shared its own analysis of the sequence.

- Rick Bright

- Brett Crozier

- Carlo Urbani, a physician who was the first to warn about severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and died of the disease in 2003

- Jiang Yanyong, a physician who was the first to reveal the actual situation of the 2003 SARS outbreak in mainland China

- Valery Legasov, a chemist who reported about the Chernobyl incident in 1986, bringing comparison with Li Wenliang in mainland China[70]

- Chen Qiushi, Fang Bin and Li Zehua, Chinese citizen journalists who went missing in February 2020 after being arrested in Wuhan

- Fang Fang, the author of Wuhan Diary

- Zhang Zhan – a citizen journalist and former lawyer who received a 4-year prison sentence for having reported about the COVID-19 pandemic

References

- Lew, Linda (9 February 2020). "Coronavirus: mother of whistle-blower Li Wenliang demands answers for his treatment by Wuhan police". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- "The Chinese doctor who tried to warn others about coronavirus". BBC News. 6 February 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- "武汉疾控证实:当地现不明原因肺炎病人,发病数在统计". The Beijing News. The Beijing News Press. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Tan, Jianxing (31 January 2020). 新冠肺炎"吹哨人"李文亮:真相最重要. Caixin (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- 武汉肺炎:一个敢于公开疫情的"吹哨人"李文亮. BBC News 中文 (in Chinese). 4 February 2020. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "Coronavirus 'kills Chinese whistleblower doctor'". BBC News. 6 February 2020. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Zhou, Cissy (7 February 2020). "Coronavirus: Whistleblower Dr Li Wenliang confirmed dead of the disease at 34, after hours of chaotic messaging from hospital". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- 武汉中心医院:李文亮经抢救无效去世 (in Chinese). Sina Corp. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- "Chinese inquiry exonerates coronavirus whistleblower doctor". The Guardian. 21 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- "Virus whistleblower doctor punished 'inappropriately': Chinese probe". The Economic Times. 20 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Ian Collier (20 March 2020). "Coronavirus: China apologises to family of doctor who died after warning about COVID-19". Sky News. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- "武汉警方:撤销对李文亮医生的训诫书,向其家属郑重道歉". 上观新闻. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "李文亮、夏思思、彭银华等33人被追授中国青年五四奖章". 中国青年报. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Kuo, Lily (3 June 2020). "'Sacrificed': anger in China over death of Wuhan doctor from coronavirus". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- 武汉市公安局武昌分局中南路街派出所训诫书 (in Chinese). Zhongnanlu Street Police Station, Wuchang Division of Wuhan Police Bureau. 3 January 2020. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- 武汉大学:李文亮校友,一路走好. The Paper (in Chinese). 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- 朱邦凌 (10 February 2020). ""吹哨人"李文亮出身"寒门":父母是下岗工人,热爱生活与家庭". 新浪网. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - 纪念李文亮:我盼望好了就上一线,不想当逃兵. 成都商报 [Chengdu Economic Daily] (in Chinese). Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- 憾别李文亮:一个"真"而"善良"的普通人走了. The Paper. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- 朱邦凌 (10 February 2020). ""吹哨人"李文亮出身"寒门":父母是下岗工人,热爱生活与家庭". 新浪. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - 鄢银婵. "李文亮厦门前同事:他就是个普通人 温柔、善良、体贴、优秀". 每日经济新闻. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - 刘名洋 (31 January 2020). 对话"传谣"被训诫医生:我是在提醒大家注意防范. 新京报网. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- UNDIAGNOSED PNEUMONIA – CHINA (HUBEI): REQUEST FOR INFORMATION. ProMed (Report). 30 December 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus: Wuhan doctor speaks out against authorities". The Guardian. 10 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- "Dr Li Wenliang: who was he and how did he become a coronavirus 'hero'?". South China Morning Post. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- 林則宏. 武漢肺炎「吹哨者」:三周前就知道可「人傳人」了. 元气网 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- 首名吹哨者李文亮已逝 武漢中心醫院官方微博證實. 世界新聞網 (in Chinese (Taiwan)). 6 February 2020. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- 武漢肺炎:最早公開疫情「吹哨人」李文亮去世. BBC Chinese (in Traditional Chinese). 6 February 2020. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "Così il regime minacciò i medici sul virus: "State zitti, è a rischio l'ordine sociale". La Stampa (in Italian). 1 February 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- 讲疫情真话被训诫的武汉医生李文亮:想尽快回到抗疫一线. The Paper (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "Death of coronavirus doctor Li Wenliang becomes catalyst for 'freedom of speech' demands in China". South China Morning Post. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "超前部署「關鍵一夜」細節曝光! 羅一鈞扮柯南追出李文亮關鍵警訊 | 匯流新聞網". cnews.com.tw (in Chinese (Taiwan)). 16 April 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- 被训诫医生李文亮去世. The Beijing News (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- 徐婷婷; 王艾冰 (7 February 2020). 年仅35岁的李文亮医生为何重症不治?. 健康时报 (in Chinese). Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- 新冠肺炎最早示警者之一李文亮医生去世. 经济观察报 (in Chinese). 6 February 2020. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Deng, Chao; Chin, Josh (6 February 2020). "Chinese Doctor Who Issued Early Warning on Virus Dies". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- 張子傑 (6 February 2020). 【武漢肺炎】敢言醫生李文亮傳死訊 院方稱仍搶救中. HK01 (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- 何雾. 李文亮于6 February 2020 晚在重症监护室去世. 界面新闻 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- 武汉市民自发送别李文亮 网民追忆纪念犹如"网络国葬" (in Simplified Chinese). Radio France Internationale. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- Austin, Henry (6 February 2020). "Chinese doctor who raised alarm over coronavirus dies from disease, hospital confirms". NBC News. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- "Wuhan hospital announces death of whistleblower doctor Li Wenliang". CNN. 6 February 2020. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "国际舆论关注李文亮去世在中国引发"罕见的网上骚动"". BBC News 中文 (in Simplified Chinese). 9 February 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Yu, Verna (7 February 2020). "'Hero who told the truth': Chinese rage over coronavirus death of whistleblower doctor". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Li, Yuan (7 February 2020). "Widespread Outcry in China Over Death of Coronavirus Doctor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Yuan, Shawn (7 February 2020). "Grief, anger in China as doctor who warned about coronavirus dies". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- 市民自发前往武汉中心医院 献花悼念李文亮医生. China Daily (in Chinese). 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- 彭琤琳, 施予 (7 February 2020). 【武漢肺炎.有片】送別李文亮 武漢市民獻花吹哨悼念. HK01 (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- 影/武漢全城吹哨子悼念李文亮 民眾醫院門口獻花. United Daily News (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- World Health Organization [@WHO] (6 February 2020). "WHO on Twitter" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Coronavirus: Wuhan police apologise to family of whistle-blowing doctor Li Wenliang". South China Morning Post. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Tenbarge, Kat (9 February 2020). "10 Wuhan professors signed an open letter demanding free speech protections after a doctor who was punished for warning others about coronavirus died from it". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- "The Right to Freedom of Speech Starts Today – An Open Letter to the National People's Congress and the NPC Standing Committee". China Change. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- Green, Andrew (29 February 2020). "Li Wenliang". The Lancet. 395 (10225): 682. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30382-2. ISSN 0140-6736.

- Paul Mozur (16 March 2020). "Coronavirus Outrage Spurs China's Internet Police to Action". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- 自由時報電子報 (7 February 2020). "被起底反港人抗爭、力挺港警! 顏擇雅:李文亮並非吹哨者 – 國際 – 自由時報電子報". Liberty Times (in Chinese). Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Zhang, Han (11 February 2020). "Grief and Wariness at a Vigil for Li Wenliang, the Doctor Who Tried to Warn China About the Coronavirus". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Cotton, Tom (3 March 2020). "S.Res.497 – 116th Congress (2019–2020): A resolution commemorating the life of Dr. Li Wenliang and calling for transparency and cooperation from the Government of the People's Republic of China and the Communist Party of China". congress.gov. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Bostock, Bill. "China declared whistleblower doctor Li Wenliang a 'martyr' following a local campaign to silence him for speaking out about the coronavirus". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- (受权发布)湖北14名新冠肺炎疫情防控一线牺牲人员被评定为首批烈士-新华网. Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "How Thousands of Chinese Gently Mourn a Virus Whistle-Blower". The New York Times. 13 April 2020. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Petersen, Eskild; Hui, David; Hamer, Davidson H.; Blumberg, Lucille; Madoff, Lawrence C.; Pollack, Marjorie; Lee, Shui Shan; McLellan, Susan; Memish, Ziad; Praharaj, Ira; Wasserman, Sean; Ntoumi, Francine; Azhar, Esam Ibraheem; McHugh, Timothy D.; Kock, Richard; Ippolito, Guiseppe; Zumla, Ali; Koopmans, Marion (3 March 2020). "Li Wenliang, a face to the frontline healthcare worker? The first doctor to notify the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2, (COVID-19), outbreak". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 93: 205–207. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.052. PMC 7129692. PMID 32142979. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Lee, Alicia (15 April 2020). "New children's book tells the story of Dr. Li Wenliang, who sounded the alarm on coronavirus". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- "Li Wenliang". Fortune.

- "White House Official Delivers Speech in Mandarin To Send Coronavirus Message". NPR. 4 May 2020. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Buckley, Chris (6 February 2020). "Chinese Doctor, Silenced After Warning of Outbreak, Dies From Coronavirus". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- "Li Wenliang: Widow of Chinese coronavirus doctor gives birth to son". BBC News. 12 June 2020.

- "Anger in China as doctor who died of Covid-19 omitted from citizen awards". The Guardian, 9 September 2020

- Tharoor, Ishaan (12 February 2020). "China's Chernobyl? The coronavirus outbreak leads to a loaded metaphor". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

External links

- Li Wenliang on Sina Weibo (in Chinese)