Lou Henry Hoover

Lou Hoover (née Henry; March 29, 1874 – January 7, 1944) was an American philanthropist, geologist, and First Lady of the United States from 1929 to 1933 as the wife of President Herbert Hoover. She was active in numerous community organizations and volunteer groups throughout her life, including the Girl Scouts of the USA, of which she was the head from 1922 to 1925 and from 1935 to 1937. Throughout her life, Hoover supported women's rights and women's independence. She was a proficient linguist, being fluent in six languages, and she was the primary translator of the complex 16th century metallurgy text De re metallica from Latin to English.

Lou Henry Hoover | |

|---|---|

| |

| First Lady of the United States | |

| In role March 4, 1929 – March 4, 1933 | |

| President | Herbert Hoover |

| Preceded by | Grace Coolidge |

| Succeeded by | Eleanor Roosevelt |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Lou Henry March 29, 1874 Waterloo, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | January 7, 1944 (aged 69) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Education | University of California, Los Angeles San José State University (DipEd) Stanford University (BA) |

| Signature | |

She was raised in California while it was part of the American frontier, and she attended Stanford University as the first female geology major in the United States. She met fellow geology student Herbert Hoover at Stanford, and they married in 1899. She traveled widely with him while he worked as a mining engineer, assisting him in his work. The Hoovers first resided in China, during which time the Boxer Rebellion broke out, and they were present for the Battle of Tientsin. They moved to London where Hoover raised their two sons and became a popular hostess between their international travels. During World War I, the Hoovers led humanitarian efforts to assist war refugees. Hoover organized refugee support and transportation in the United Kingdom and went on fundraising tours in the United States. The family moved to Washington, D.C. when Herbert was appointed head of the Food and Drug Administration, and Lou became a conservation activist in support of his work.

Hoover became the First Lady of the United States when her husband was inaugurated as president in 1929. She minimized her public role as White House hostess, dedicating her time as first lady to her volunteer work. She refused to give interviews to reporters, but she became the first first lady to give regular radio broadcasts. Her invitation of Jessie De Priest to the White House for tea was controversial for its implied support of racial integration and civil rights. Hoover was responsible for refurbishing the White House during her tenure, and she also saw to the construction of a presidential retreat at Rapidan Camp. Hoover's reputation declined alongside her husband's during the Great Depression as she was seen as uncaring of the struggles faced by Americans. Both the public and those close to her were unaware of her extensive charitable work to support the poor while serving as first lady, as she believed that publicizing generosity was improper.

After her husband lost his reelection campaign in 1932, the Hoovers returned to California, and they moved to New York City in 1940. Hoover was bitter about her husband's loss, blaming dishonest reporting and underhanded campaigning tactics, and she strongly opposed the Roosevelt administration. She provided humanitarian support with her husband during World War II until her sudden death of a heart attack in 1944.

Early life and education

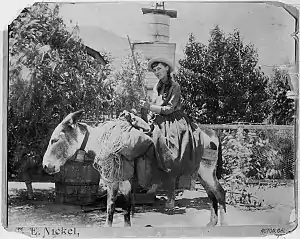

Lou Henry was born in Waterloo, Iowa, to Florence Ida (née Weed) and Charles Delano Henry, who was a banker by trade.[1] She was the older of two daughters, raised first in Waterloo, and later in the California towns of Whittier and Monterey.[2] She was proficient in school, receiving a traditional education so she could become a teacher. While she was a child, Lou's father educated her in outdoorsmanship, and she learned to camp, shoot, and ride.[3] She took up sports, including baseball, basketball, and archery.[2] Her parents also taught her other practical skills, such as bookkeeping and sewing. Her family was nominally Episcopalian, but they were close to the local Quaker community.[4]

Henry began her postsecondary schooling at the Los Angeles Normal School (now the University of California, Los Angeles). She then transferred to San Jose Normal School (now San José State University), from which she obtained a teaching credential in 1893.[2] After graduation, she took a job at her father's bank in addition to working as a substitute teacher. The following year, she attended a lecture by geologist John Casper Branner. Fascinated by the subject, she enrolled in Branner's program at Stanford University to pursue a degree in geology. It was there that Branner introduced her to her future husband, Herbert Hoover, who was then a senior. The two became friends, and the friendship evolved into a courtship.[5] She studied geology with the intention of doing field work, but she and Branner were unable to find any employers willing to accept a female geologist.[6] She was the school’s only female geology major at the time, and received her bachelor's degree in geology in 1898.[7] She was the first woman in the United States to hold such a degree.[6][8]

Marriage and travels

Marriage and travel to China

In 1897, Herbert was offered an engineering job in Australia. Before leaving, he had dinner with the Henrys and their engagement was informally agreed upon.[9] While he was in Australia, Lou and Herbert maintained a long-distance relationship.[10] He sent her a marriage proposal by cable, reading "Going to China via San Francisco. Will you go with me?".[9] They were married in the Henry's home on February 10, 1899. Lou also announced her intention to change her religious faith from Episcopalian to her husband's Quaker religion, but there was no Quaker Meeting in Monterey, and she never did so. Instead, they were married in a civil ceremony performed by a Spanish Roman Catholic priest at her family home.[4]

The day after their marriage, the Hoovers sailed from San Francisco, and they briefly honeymooned at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu.[9] They arrived in Shanghai on March 8, where they spent four days in the Astor House Hotel.[11] Hoover stayed with a missionary couple in the foreign colony in Tientsin (now Tianjin) while her husband was working, and they moved into a home of their own the following September.[12] It was their first home as a married couple, a Western-style brick house at the edge of the colony. It was here that Hoover began homemaking and interior decoration. Within the home, she managed a staff and entertained for guests.[4] She also took up typing while in China, purchasing a typewriter and writing scientific articles on Chinese mining with her husband.[13] While in China, she started a collection of Chinese porcelain that she would maintain throughout her life.[7]

The Hoovers lived in China until August 1900. The Boxer Rebellion began while they lived in China, and despite her husband's pleas, she refused to leave his side amidst the danger. They participated in the Battle of Tientsin in 1900, with Lou serving as a nurse while Herbert worked as an engineer.[14] Artillery shelling was a constant danger throughout the conflict.[15] For a month, Hoover carried a revolver while she ran supplies to soldiers on her bicycle. As foreigners, they were in particular danger during the conflict, including one instance in which Hoover's bicycle tire was shot out while she was riding. One Monterey newspaper mistakenly published her obituary.[16] They would briefly return to China once more with Lou's sister Jean for several months in 1901, at which point the Boxer Rebellion had ended and China was safe for tourists.[17]

London and World War I

From China, the Hoovers moved their primary residence to London, which would remain the Hoover's primary residence while they traveled for work. Herbert became an independent mining consultant, and his work made them millionaires.[18] Because of their travels, Hoover spent much time on steamboats; the trips were relatively comfortable as they traveled in first class, and she spent much of her time on these months-long voyages by reading or by hosting social visits with other travelers using portable tea sets and tables.[19] Their work took them throughout Europe and to many other countries, including Australia, Burma, Ceylon, Egypt, India, Japan, New Zealand, and Russia.[7] The Hoovers had two sons who would accompany them as they traveled. Herbert Hoover Jr. was born in 1903, and Allan Hoover was born in 1907.[20]

As a proficient geologist in her own right, Hoover would often assist her husband in his work as a geological engineer.[18] Her expertise in geology allowed her to participate in business talk with her husband and his colleagues, which she thoroughly enjoyed.[21] The Hoovers played a role in standardizing the modern mining industry, particularly in regard to human management and business ethics.[16] When they were in London, Lou often entertained large crowds, as their home became a social hub for their fellow immigrants in London.[15] They also had frequent company from mining engineers, as members of the occupation were generally familiar with one another.[22] The Hoovers engaged in philanthropy during their time in London, and Lou would see to it that all of her friends and her servants had their needs addressed. She joined the Friends of the Poor to work directly with people in poverty, and she joined social clubs such as the Society of American Women, the British affiliate of the General Federation of Women's Clubs. She participated in and eventually led the society's philanthropic committee.[23]

When World War I began, the Hoovers had already spent time back in the United States and were preparing to move back permanently. Upon hearing that war broke out, Lou reorganized the Society of American Women as a humanitarian group to organize the transport of Americans stranded in Britain.[24] The Hoovers stayed in London and continued to provide humanitarian relief throughout the war. While Herbert worked on international humanitarianism, Lou ensured refugees had access to food, raised funds to provide further support, and served as the only woman on the repatriation board.[25] In carrying out her work, she made several trips between the United States and the United Kingdom despite the danger of crossing the North Atlantic during the war.[26] She was also involved with the American Women's War Relief Fund, which provided ambulances, funded two hospitals, and provided economic opportunities for women during the war.[27] As her humanitarian efforts increased, she found herself responsible for several major operations and had to delegate several projects to similarly motivated women.[28] For her work, she was decorated in 1919 by King Albert I of Belgium.[7]

Return to the United States

The Hoovers returned their primary residence to the United States in January 1917. The United States entered World War I three months later, at which point Herbert was appointed head of the Food and Drug Administration and they made their home in Washington, D.C.[29] Working in coordination with her husband, Lou took up the cause of food conservation in addition to her war relief efforts. The Hoovers effectively became the public faces of the conservation movement.[20] She also organized the construction of a family home by Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, but this was seen as selfish amidst her humanitarian work and she delayed the project until the end of the war.[30]

The war brought thousands of women to Washington to work as civil servants. The poor economic security of these women led Hoover to found women's groups and provide housing for the women that worked in her husband's department.[31] She expanded her support for these women's groups to include medical treatment during the Spanish flu.[32] Hoover paid for these programs with her own funds, describing them as loans but asking that they be repaid to someone that needs it more.[33]

After the war, Herbert was appointed Secretary of Commerce, and the family returned to Washington. Lou got involved with new projects, including the Girl Scouts of the USA and the Women's Division of the National Amateur Athletic Foundation.[34] Her work with the Girl Scouts led to her serving as the group's president from 1922 to 1925.[35] She also founded racially integrated Girl Scout troops in Washington and Palo Alto.[7] When Calvin Coolidge ascended to the presidency, Hoover became close friends with the new first lady, Grace Coolidge. The two of them began a tradition of exchanging flowers on Easter, and Hoover invited Coolidge to participate in Girl Scouts events.[36]

When Herbert was considered as a candidate for the 1928 presidential election, Lou did not approve of active campaigning, and Herbert often refrained from political talk when she was present. Despite this, she recognized the importance of the campaign and gave him her full support. She traveled the country with him while he campaigned, supplementing his campaign with her charisma.[37] The campaign brought more attention to the candidate's wives than those of previous years. When her husband was chosen as the Republican Party's nominee, she found herself frequently compared to Catherine Smith, the wife of Democratic candidate Al Smith. Hoover was relatively popular compared to Mrs. Smith, who was an urbanite, a Catholic, and an alleged alcoholic. Hoover was seen as better fit for the roll, being athletic and well-traveled.[38] After Herbert was elected president, Lou accompanied him on a goodwill tour in Latin America.[39]

First Lady of the United States

Hoover did not prioritize public presentations as first lady. When she took up the role, she declined to purchase new clothes or take up skills as new first ladies often did.[40]Throughout her tenure, she refused to give interviews to the press and was seen as aloof. She was, however, the first woman to make radio broadcasts as first lady.[8] She took pride in her broadcasts, rehearsing them in a dedicated room and practicing her speaking technique. These broadcasts often used plain language and advocated feminist ideals.[40] She also encouraged her husband to hire more women in his administration, and she expressed support for an executive order to ban sex discrimination in civil service appointments.[41] Hoover continued her involvement with the Girl Scouts while serving as first lady, including its organizational and financial operations.[42] She generally avoided any strong political statements or affiliations that may have interfered with her husband's administration.[7]

Hoover was often reclusive as first lady. She was unhappy with her obligation to greet thousands during the New Year's Day reception, so she ended the practice. Her husband would later state that it was only her "rigid sense of duty" that prevented her from abolishing others receptions as well. Hoover required the staff to remain out of sight, and a bell would be rung before she or her husband entered a room, signaling for the staff to leave the area. While managing White House events, she would use hand signals to communicate with the staff. Many innocuous gestures, such as raising a finger or dropping a handkerchief, indicated a command to the staff.[40] Hoover was not as successful in her role as White House hostess as she was in other projects; she was not eager to participate in Washington society except on her own terms, and her social position became increasingly precarious as the Hoovers' reputation diminished during the Great Depression.[43]

When African American candidate Oscar Stanton De Priest was elected to Congress, Hoover initiated a meeting for tea at the White House with his wife Jessie De Priest, as was tradition for the wives of all incoming Congressmen. Hoover was responsible for planning the event to ensure its success.[34] She arranged the scheduling so that only women she trusted would be attending the event, and she alerted White House security that Mrs. De Priest was to be expected and not barred entry.[44] The event became part of a larger debate on racial issues as southern voters protested the invitation of a Black woman.[34] It further complicated Hoover's relationship with the press, as she deemed Southern newspapers to be responsible for the criticism. The Hoovers would reinforce the precedent by inviting the Tuskegee Institute choir to the White House.[45]

Hoover oversaw refurbishing of the White House, importing art and furniture to decorate the building while also cataloguing the existing furnishings.[46] She worked in conjunction with a committee that had been formed in the previous administration to decorate the White House, though she sometimes declined to consult them and made her own changes. She catalogued the historical furniture of the White House, and she had a movie projector installed.[47] Her refurbishing included the reconstruction of the studies of Abraham Lincoln and James Monroe, which would later be converted into the Lincoln Bedroom and the Treaty Room, respectively.[7] She also played a critical role in designing and overseeing the construction of a rustic presidential retreat at Rapidan Camp in Madison County, Virginia.[34] After the location was chosen, the Hoovers discovered the poverty in the area and included the construction of a school building to their project.[46] They undertook another philanthropic construction project in 1930 to build a Quaker Meeting in Washington.[48]

Hoover became a patron of the arts as first lady, particularly in her support of aspiring musicians.[49] During the Great Depression, Hoover received countless letters from families needing assistance. She addressed many of these letters by sending care packages and personal checks or by expediting assistance through charities and government agencies. She refused to publicize or draw attention to her charitable work, consistent with her lifelong belief that private generosity should not be promotional.[50] She became responsible for the financial situation of her and Herbert's relatives and family friends in particular.[51] Hoover also helped organize fundraiser concerts for the American Red Cross with pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski.[7] She was deeply affected by the criticisms leveled against her husband during the Great Depression, furious that a man she saw as caring and charitable was being criticized as the opposite.[52] She accompanied Herbert on a presidential campaign again in 1932, but they would retire from the White House after his loss in the 1932 presidential election.[53]

Later life and death

.jpg.webp)

After leaving the White House, the Hoovers took their first true vacation in many years, driving through the Western United States. She continued to receive letters requesting assistance, though far fewer than she had addressed while serving as first lady.[54] In 1935, Hoover took up a project to purchase and restore her husband's birthplace cottage in Iowa.[55] Hoover continued her previous volunteer work after serving as first lady. She returned to the Girl Scouts to serve as its president a second time from 1935 to 1937.[35] She returned to Stanford University to develop its music program,[34] and she supported a physical therapy program that would prove beneficial should the United States go to war.[7]

Hoover was concerned by the actions of the Roosevelt administration, and she became affiliated with the Pro-America movement that opposed the New Deal.[56] At the onset of World War II, she once again worked to provide relief for war refugees in tandem with her husband, reminiscent of their work in World War I.[57] She took an isolationist stance, hoping that the United States would not enter the second World War as it entered the first. During the 1940 presidential election, the Hoovers campaigned on behalf of Republican candidate Wendell Willkie. The Hoovers moved to New York in December 1940, as Herbert had been spending an increasing amount of time there on business.[58]

Hoover died of a heart attack in New York City on January 7, 1944. She was found dead in her bedroom by her husband, who came to kiss her good night. Herbert was devastated by her death and never considered remarrying.[59] After her death, Herbert found hundreds of checks she had received to repay her for her charitable work, which she had declined to cash.[60] A joint Episcopalian-Quaker service was held in New York, attended by about one thousand people, including two hundred girl scouts. A second service was held in Palo Alto, where she was buried. Following Herbert's death in 1964, she was reinterred next to her husband's at West Branch, Iowa.[61]

Political beliefs

.jpg.webp)

Throughout her life, Hoover worked to support women's causes. She was an advocate of women's employment, encouraging housewives to start careers in addition to keeping house.[62] Hoover lived by this belief, maintaining an active role in her husband's work and in her own humanitarian projects.[18] Her support for women's causes came about early in life, and she wrote multiple school essays on the subject.[7] When the Nineteenth Amendment guaranteed women's suffrage in the United States in 1920, Hoover said that women's responsibilities extended to civic duty.[63] She was a member of several women's groups, many of which engaged in philanthropic efforts to support women.[23][27] Hoover also supported civil rights on racial grounds and deplored racism, though she was susceptible to the racial stereotyping that was common at the time, and she was unaware of problems faced by the African American community.[44]

Hoover was a strong believer in philanthropy and business ethics, supporting her husband's decision to reimburse his employers at personal expense after a fellow partner defrauded them. She also ensured that the culprit's family was cared for financially after he fled the country.[16] Hoover was not vocal about her beliefs, preferring to practice them quietly. Outside of women's issues, she rarely expressed political ideas of her own, presenting a unified position with the stances of her husband.[64] She opposed publicized philanthropy, and she gave funds to the needy throughout her life without telling others. The full extent of her philanthropy was not known until records were discovered after her death.[65] She held a similar philosophy regarding religion, believing that practice was more important than sectarian identification.[48]

While her husband was the head of the Food and Drug Administration, Hoover took up the cause of food conservation. She began a tradition of leaving one chair empty as a reminder of child starvation whenever she entertained company.[41] In 1918, she invited reporters into her home for a special "Dining with the Hoovers" interview in which she detailed their household's dining habits and conservation strategies.[66] The practice of self-imposed dietary restrictions to conserve, such as going one day a week without meat, became known as "Hoovering". She provided lessons and recipes for Americans that wished to grow or prepare their own food.[7]

During the Teapot Dome scandal, Hoover took an active stance in favor of government accountability.[41] The scandal led her to call for more women in law enforcement,[67] and she headed the Women's Conference on Law Enforcement in 1924.[7] As first lady, Hoover provided indirect support to disabled veterans of the Bonus Army, though she believed that the able-bodied veterans had no claim to the additional support they were requesting. She was highly sensitive to political criticism as first lady, and she was strongly affected by remarks against her husband's presidency.[7]

Hoover became more conservative after her tenure as first lady, and she was critical of the Roosevelt administration.[34] Despite their political differences, Hoover has been compared to her successor Eleanor Roosevelt in their common approaches to political engagement and women's issues.[68] Hoover held the Roosevelts in disregard, believing that they caused her husband to be politically smeared and costed him a second term in the White House. She also felt that many of President Roosevelt's actions were unconstitutional.[7] She also made political statements later in life to protest the spread of communism and fascism.[56]

Languages

.jpg.webp)

Hoover studied linguistics and foreign language, attaining fluency in six languages as she traveled with her husband.[18] In addition to English, she studied Mandarin, Latin, Spanish, German, Italian, and French.[69]

She began her study of Mandarin Chinese while on the ship to China after her marriage.[4] She took up instruction under a Chinese Christian scholar, eventually surpassing him in her Chinese vocabulary. She sometimes served as her husband's translator while they lived in China, and she would continue to practice Chinese with him afterward so that he would retain the little that he knew.[70] When she wished to speak privately with her husband in the White House, Hoover would engage with him in Mandarin.[10] Her Chinese name was 'Hoo Loo' (古鹿; Pinyin: Gǔ Lù【胡潞,Hú Lù】), derived from the sound of her name in English.[71]

She was also well versed in Latin, which she studied while at Stanford.[7] She collaborated with her husband in translating Agricola's De Re Metallica, a 16th-century encyclopedia of mining and metallurgy. Lou was responsible for the linguistic translation, while Herbert applied his knowledge of the subject matter and carried out physical experiments based on what they discerned from the text. The book had previously been considered lost due to the difficulty of translating its technical language, some of which had been invented by its author. After its translation, the Hoovers published it at their own expense and donated copies to students and experts of mining.[72] In recognition of their work, they received the gold medal of the Mining and Metallurgical Society of America in 1914.[20] They dedicated the book to Dr. Branner, the instructor that introduced Lou to geology and to Herbert.[73]

Legacy

During her tenure as first lady, Hoover was portrayed as a homemaker, as was common for first ladies, but she was also portrayed as an activist. Her reputation, following that of her husband, languished as the Hoover administration was criticized for its response to the Great Depression. The first biography written about Hoover was Lou Henry Hoover: Gallant First Lady, written by her friend Helen B. Pryor in 1969. Hoover's papers were opened in 1985, allowing for increased scholarship on her life and her work.[74] Historical study of Hoover is complicated by her private nature, as she would often refuse media attention and burn personal letters. Hoover is seen as a counterbalance to her husband as she took up the social responsibilities of their work in and out of the White House, her charisma and tact balancing his reputation of being shy and sometimes arrogant.[75] The Hoovers' relationship with their staff is the subject of debate; memoirs of staff members have portrayed them in a negative light, but it is unclear how much of this depiction originates from the books' ghostwriters.[76]

The Stanford home that Hoover designed was donated to the university by her husband, who requested that it be named the Lou Henry Hoover House.[77] Two elementary schools were named in her honor: Lou Henry Hoover Elementary School of Whittier, California in 1938 and Lou Henry Elementary School of Waterloo, Iowa in 2005.[7] Lou Henry Hoover Memorial Hall was built in 1948 at Whittier College, where she had been a trustee until her death.[78] One of the brick dorms at San Jose State University was named "Hoover Hall" in her honor until its demolition in 2016.[79]

Camp Lou Henry Hoover in Middleville, New Jersey, is named for her and run by the Heart of New Jersey Council of the Girl Scouts.[80] She funded the construction of the first Girl Scout house in Palo Alto, California. The house is in continuous use, now called Lou Henry Hoover Girl Scout House.[81]

See also

- Margaret Hoover – Hoover's great-granddaughter

References

- Hart, Craig (2004). A genealogy of the wives of the American presidents and their first two generations of descent. North Carolina, Jefferson: McFarland & Co., Inc., pp. 129–33

- Watson 2001, p. 212.

- Schwartz Foster 2011, p. 131.

- Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 221.

- Allen 2000, pp. 15–16.

- Allen 2000, p. 19.

- "First Lady Biography: Lou Hoover". National First Ladies' Library. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- Beasley, Maurine H. (2005). First Ladies and the Press: The Unfinished Partnership of the Media Age. Northwestern University Press. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-0-8101-2312-0.

- Allen 2000, pp. 20–21.

- Watson 2001, p. 213.

- Allen 2000, p. 23.

- Allen 2000, p. 24–26.

- Allen 2000, p. 28.

- "Herbert Hoover and China". World Association for International Studies. November 21, 2001. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

The Hoovers arrived in China in April 1899 and lived through the siege of Tienjin. Being an engineer, Mr. Hoover and his detail were responsibie for maintaining the battleworks; Mrs. Hoover worked as a nurse. Although both Hoovers knew how to fire a gun, there is no evidence that they ever shot at the boxers. They left China in August 1900.

- Caroli 2010, p. 179.

- Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 222.

- Allen 2000, pp. 37–38.

- Schwartz Foster 2011, p. 132.

- Allen 2000, pp. 48–49.

- Watson 2001, p. 214.

- Allen 2000, pp. 38–39.

- Allen 2000, p. 51.

- Allen 2000, pp. 52–53.

- Allen 2000, pp. 61–62.

- Schwartz Foster 2011, p. 133.

- Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 223.

- "Helping in Britain: The American Women's War Relief Fund". American Women in World War I. January 9, 2017. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- Allen 2000, pp. 67–68.

- Allen 2000, p. 71.

- Allen 2000, p. 73.

- Allen 2000, pp. 73–74.

- Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 224.

- Allen 2000, p. 4.

- Young 2016, p. 425.

- "Lou Hoover and Girl Scouts". Hoover Presidential Library. August 30, 2017.

- Allen 2000, p. 106.

- Allen 2000, pp. 115–117.

- Caroli 2010, p. 182.

- Allen 2000, p. 118.

- Caroli 2010, p. 183.

- Watson 2001, p. 215.

- Allen 2000, pp. 138–139.

- Allen 2000, p. 128.

- Allen 2000, pp. 130–131.

- Watson 2001, pp. 215–216.

- Watson 2001, p. 216.

- Allen 2000, pp. 122–123.

- Allen 2000, pp. 136–137.

- Allen 2000, p. 132.

- Schwartz Foster 2011, p. 136.

- Allen 2000, p. 144.

- Allen 2000, p. 147.

- Allen 2000, pp. 151–152.

- Allen 2000, pp. 154–157.

- Allen 2000, pp. 162–163.

- Allen 2000, pp. 165–166.

- Watson 2001, p. 217.

- Allen 2000, pp. 167–168.

- Jeansonne, Glen; Luhrssen, David (2016). Herbert Hoover: A Life. Penguin. p. 350. ISBN 9781101991008.

- Schwartz Foster 2011, p. 137.

- Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 228.

- Caroli 2010, p. 185.

- Allen 2000, p. 105.

- Caroli 2010, p. 187.

- Schwartz Foster 2011, pp. 136–137.

- Caroli 2010, p. 181.

- Schneider & Schneider 2010, p. 225.

- Young 2016, p. 428.

- "An Uncommon Couple: Herbert and Lou Henry Hoover". Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- Allen 2000, p. 24.

- Whyte, Kenneth (2017). Hoover: An Extraordinary Life in Extraordinary Times. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 73. ISBN 9780307743879.

- Schneider & Schneider 2010, pp. 222–223.

- Allen 2000, p. 50.

- Young 2016, p. 432.

- Allen 2000, pp. 1–2.

- Allen 2000, pp. 120–121.

- Allen 2000, p. 173.

- "Historic Campus Architecture Project: Lou Henry Hoover Memorial Hall". Council of Independent Colleges. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- "The red brick dorms at San Jose State come down". The Mercury News. November 30, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- "Camp Lou Henry Hoover History" (PDF). Girl Scouts Heart of New Jersey. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 7, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- "Girl Scouts Palo Alto, California". Palo Alto Service Unit. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

Bibliography

- Allen, Anne Beiser (2000). An Independent Woman: The Life of Lou Henry Hoover. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313314667.

- Caroli, Betty (2010). First Ladies: From Martha Washington to Michelle Obama. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 176–188. ISBN 978-0-19-539285-2.

- Schneider, Dorothy; Schneider, Carl J. (2010). "Lou Henry Hoover". First Ladies: A Biographical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Facts on File. pp. 220–229. ISBN 978-1-4381-0815-5.

- Schwartz Foster, Feather (2011). "Lou Hoover". The First Ladies: From Martha Washington to Mamie Eisenhower, an Intimate Portrait of the Women Who Shaped America. Cumberland House. pp. 131–137. ISBN 978-1-4022-4272-4.

- Watson, Robert P. (2001). "Lou Henry Hoover". First Ladies of the United States. Lynne Rienner Publishers. pp. 212–217. doi:10.1515/9781626373532. ISBN 978-1-62637-353-2. S2CID 249333854.

- Young, Nancy Beck (2016). "The Historiography of Lou Henry Hoover". In Sibley, Katherine A. S. (ed.). A Companion to First Ladies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 423–438. ISBN 9781118732182.

External links

- Lou Hoover at C-SPAN's First Ladies: Influence & Image

- Herbert Hoover Presidential Library & Museum

- Biography of Lou Henry Hoover Hosted by the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library & Museum

- Lou Henry Hoover Papers

- Biographical sketch of Lou Henry Hoover Hosted by the National Archives and Records Administration

- Lou Henry Hoover at Find a Grave

- Works by Lou Henry Hoover at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Lou Henry Hoover at Internet Archive