Mahayana

Mahāyāna (/ˌmɑːhəˈjɑːnə/; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the two main existing branches of Buddhism (the other being Theravāda).[1] Mahāyāna accepts the main scriptures and teachings of early Buddhism, but also recognizes various doctrines and texts which are not accepted by Theravada Buddhism as original. These include the Mahāyāna Sūtras and its emphasis on the bodhisattva path and Prajñāpāramitā.[2] Vajrayāna or Mantra traditions are a subset of Mahāyāna, which make use of numerous tantric methods considered to be faster and more powerful at achieving Buddhahood by Vajrayānists.[1]

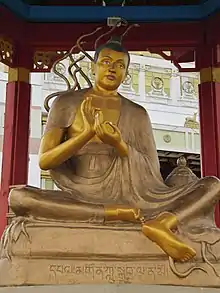

| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

"Mahāyāna" also refers to the path of the bodhisattva striving to become a fully awakened Buddha (samyaksaṃbuddha) for the benefit of all sentient beings, and is thus also called the "Bodhisattva Vehicle" (Bodhisattvayāna).[3][note 1] Mahāyāna Buddhism generally sees the goal of becoming a Buddha through the bodhisattva path as being available to all and sees the state of the arhat as incomplete.[4] Mahāyāna also includes numerous Buddhas and bodhisattvas that are not found in Theravada (such as Amitābha and Vairocana).[5] Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy also promotes unique theories, such as the Madhyamaka theory of emptiness (śūnyatā), the Vijñānavāda doctrine and the Buddha-nature teaching.

Although it was initially a small movement in India, Mahāyāna eventually grew to become an influential force in Indian Buddhism.[6] Large scholastic centers associated with Mahāyāna such as Nalanda and Vikramashila thrived between the seventh and twelfth centuries.[6] In the course of its history, Mahāyāna Buddhism spread throughout South Asia, Central Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. It remains influential today in China, Mongolia, Hong Kong, Korea, Japan, Singapore, Vietnam, Nepal, Malaysia, Taiwan and Bhutan.[7]

The Mahāyāna tradition is the largest major tradition of Buddhism existing today (with 53% of Buddhists belonging to East Asian Mahāyāna and 6% to Vajrayāna), compared to 36% for Theravada (survey from 2010).[8]

Etymology

Original Sanskrit

According to Jan Nattier, the term Mahāyāna ("Great Vehicle") was originally an honorary synonym for Bodhisattvayāna ("Bodhisattva Vehicle"),[9] the vehicle of a bodhisattva seeking buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings.[3] The term Mahāyāna (which had earlier been used simply as an epithet for Buddhism itself) was therefore adopted at an early date as a synonym for the path and the teachings of the bodhisattvas. Since it was simply an honorary term for Bodhisattvayāna, the adoption of the term Mahāyāna and its application to Bodhisattvayāna did not represent a significant turning point in the development of a Mahāyāna tradition.[9]

The earliest Mahāyāna texts, such as the Lotus Sūtra, often use the term Mahāyāna as a synonym for Bodhisattvayāna, but the term Hīnayāna is comparatively rare in the earliest sources. The presumed dichotomy between Mahāyāna and Hīnayāna can be deceptive, as the two terms were not actually formed in relation to one another in the same era.[10]

Among the earliest and most important references to Mahāyāna are those that occur in the Lotus Sūtra (Skt. Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra) dating between the 1st century BCE and the 1st century CE.[11] Seishi Karashima has suggested that the term first used in an earlier Gandhāri Prakrit version of the Lotus Sūtra was not the term mahāyāna but the Prakrit word mahājāna in the sense of mahājñāna (great knowing).[12][13] At a later stage when the early Prakrit word was converted into Sanskrit, this mahājāna, being phonetically ambivalent, may have been converted into mahāyāna, possibly because of what may have been a double meaning in the famous Parable of the Burning House, which talks of three vehicles or carts (Skt: yāna).[note 2][12][14]

Chinese translation

In Chinese, Mahāyāna is called 大乘 (dacheng), which is a calque of maha (great 大) yana (vehicle 乘). There is also the transliteration 摩诃衍那.[15][16] The term appeared in some of the earliest Mahāyāna texts, including Emperor Ling of Han's translation of the Lotus Sutra.[17] It also appears in the Chinese Āgamas, though scholars like Yin Shun argue that this is a later addition.[18][19][20] Some Chinese scholars also argue that the meaning of the term in these earlier texts is different than later ideas of Mahāyāna Buddhism.[21]

History

Origin

The origins of Mahāyāna are still not completely understood and there are numerous competing theories.[22] The earliest Western views of Mahāyāna assumed that it existed as a separate school in competition with the so-called "Hīnayāna" schools. Some of the major theories about the origins of Mahāyāna include the following:

The lay origins theory was first proposed by Jean Przyluski and then defended by Étienne Lamotte and Akira Hirakawa. This view states that laypersons were particularly important in the development of Mahāyāna and is partly based on some texts like the Vimalakirti Sūtra, which praise lay figures at the expense of monastics.[23] This theory is no longer widely accepted since numerous early Mahāyāna works promote monasticism and asceticism.[24][25]

The Mahāsāṃghika origin theory, which argues that Mahāyāna developed within the Mahāsāṃghika tradition.[24] This is defended by scholars such as Hendrik Kern, A.K. Warder and Paul Williams who argue that at least some Mahāyāna elements developed among Mahāsāṃghika communities (from the 1st century BCE onwards), possibly in the area along the Kṛṣṇa River in the Āndhra region of southern India.[26][27][28][29] The Mahāsāṃghika doctrine of the supramundane (lokottara) nature of the Buddha is sometimes seen as a precursor to Mahāyāna views of the Buddha.[5] Some scholars also see Mahāyāna figures like Nāgārjuna, Dignaga, Candrakīrti, Āryadeva, and Bhavaviveka as having ties to the Mahāsāṃghika tradition of Āndhra.[30] However, other scholars have also pointed to different regions as being important, such as Gandhara and northwest India.[31][note 3][32]

The Mahāsāṃghika origins theory has also slowly been shown to be problematic by scholarship that revealed how certain Mahāyāna sutras show traces of having developed among other nikāyas or monastic orders (such as the Dharmaguptaka).[33] Because of such evidence, scholars like Paul Harrison and Paul Williams argue that the movement was not sectarian and was possibly pan-buddhist.[24][34] There is no evidence that Mahāyāna ever referred to a separate formal school or sect of Buddhism, but rather that it existed as a certain set of ideals, and later doctrines, for aspiring bodhisattvas.[17]

The "forest hypothesis" meanwhile states that Mahāyāna arose mainly among "hard-core ascetics, members of the forest dwelling (aranyavasin) wing of the Buddhist Order", who were attempting to imitate the Buddha's forest living.[35] This has been defended by Paul Harrison, Jan Nattier and Reginald Ray. This theory is based on certain sutras like the Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra and the Mahāyāna Rāṣṭrapālapaṛiprcchā which promote ascetic practice in the wilderness as a superior and elite path. These texts criticize monks who live in cities and denigrate the forest life.[36][37]

Jan Nattier's study of the Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra, A few good men (2003) argues that this sutra represents the earliest form of Mahāyāna, which presents the bodhisattva path as a 'supremely difficult enterprise' of elite monastic forest asceticism.[24] Boucher's study on the Rāṣṭrapālaparipṛcchā-sūtra (2008) is another recent work on this subject.[38]

The cult of the book theory, defended by Gregory Schopen, states that Mahāyāna arose among a number of loosely connected book worshiping groups of monastics, who studied, memorized, copied and revered particular Mahāyāna sūtras. Schopen thinks they were inspired by cult shrines where Mahāyāna sutras were kept.[24] Schopen also argued that these groups mostly rejected stupa worship, or worshiping holy relics.

David Drewes has recently argued against all of the major theories outlined above. He points out that there is no actual evidence for the existence of book shrines, that the practice of sutra veneration was pan-Buddhist and not distinctly Mahāyāna. Furthermore, Drewes argues that "Mahāyāna sutras advocate mnemic/oral/aural practices more frequently than they do written ones."[24] Regarding the forest hypothesis, he points out that only a few Mahāyāna sutras directly advocate forest dwelling, while the others either do not mention it or see it as unhelpful, promoting easier practices such as "merely listening to the sutra, or thinking of particular Buddhas, that they claim can enable one to be reborn in special, luxurious 'pure lands' where one will be able to make easy and rapid progress on the bodhisattva path and attain Buddhahood after as little as one lifetime."[24]

Drewes states that the evidence merely shows that "Mahāyāna was primarily a textual movement, focused on the revelation, preaching, and dissemination of Mahāyāna sutras, that developed within, and never really departed from, traditional Buddhist social and institutional structures."[39] Drewes points out the importance of dharmabhanakas (preachers, reciters of these sutras) in the early Mahāyāna sutras. This figure is widely praised as someone who should be respected, obeyed ('as a slave serves his lord'), and donated to, and it is thus possible these people were the primary agents of the Mahāyāna movement.[39]

Early Mahāyāna

The earliest textual evidence of "Mahāyāna" comes from sūtras ("discourses", scriptures) originating around the beginning of the common era. Jan Nattier has noted that some of the earliest Mahāyāna texts, such as the Ugraparipṛccha Sūtra use the term "Mahāyāna", yet there is no doctrinal difference between Mahāyāna in this context and the early schools. Instead, Nattier writes that in the earliest sources, "Mahāyāna" referred to the rigorous emulation of Gautama Buddha's path to Buddhahood.[17]

Some important evidence for early Mahāyāna Buddhism comes from the texts translated by the Indoscythian monk Lokakṣema in the 2nd century CE, who came to China from the kingdom of Gandhāra. These are some of the earliest known Mahāyāna texts.[40][41][note 4] Study of these texts by Paul Harrison and others show that they strongly promote monasticism (contra the lay origin theory), acknowledge the legitimacy of arhatship, do not recommend devotion towards 'celestial' bodhisattvas and do not show any attempt to establish a new sect or order.[24] A few of these texts often emphasize ascetic practices, forest dwelling, and deep states of meditative concentration (samadhi).[42]

Indian Mahāyāna never had nor ever attempted to have a separate Vinaya or ordination lineage from the early schools of Buddhism, and therefore each bhikṣu or bhikṣuṇī adhering to the Mahāyāna formally belonged to one of the early Buddhist schools. Membership in these nikāyas, or monastic orders, continues today, with the Dharmaguptaka nikāya being used in East Asia, and the Mūlasarvāstivāda nikāya being used in Tibetan Buddhism. Therefore, Mahāyāna was never a separate monastic sect outside of the early schools.[43]

Paul Harrison clarifies that while monastic Mahāyānists belonged to a nikāya, not all members of a nikāya were Mahāyānists.[44] From Chinese monks visiting India, we now know that both Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna monks in India often lived in the same monasteries side by side.[45] It is also possible that, formally, Mahāyāna would have been understood as a group of monks or nuns within a larger monastery taking a vow together (known as a "kriyākarma") to memorize and study a Mahāyāna text or texts.[46]

"Bu-ddha-sya A-mi-tā-bha-sya"

"Of the Buddha Amitabha"[48]

The earliest stone inscription containing a recognizably Mahāyāna formulation and a mention of the Buddha Amitābha (an important Mahāyāna figure) was found in the Indian subcontinent in Mathura, and dated to around 180 CE. Remains of a statue of a Buddha bear the Brāhmī inscription: "Made in the year 28 of the reign of King Huviṣka, ... for the Blessed One, the Buddha Amitābha."[48] There is also some evidence that the Kushan Emperor Huviṣka himself was a follower of Mahāyāna. A Sanskrit manuscript fragment in the Schøyen Collection describes Huviṣka as having "set forth in the Mahāyāna."[49] Evidence of the name "Mahāyāna" in Indian inscriptions in the period before the 5th century is very limited in comparison to the multiplicity of Mahāyāna writings transmitted from Central Asia to China at that time.[note 5][note 6][note 7]

Based on archeological evidence, Gregory Schopen argues that Indian Mahāyāna remained "an extremely limited minority movement – if it remained at all – that attracted absolutely no documented public or popular support for at least two more centuries."[24] Likewise, Joseph Walser speaks of Mahāyāna's "virtual invisibility in the archaeological record until the fifth century."[50] Schopen also sees this movement as being in tension with other Buddhists, "struggling for recognition and acceptance".[51] Their "embattled mentality" may have led to certain elements found in Mahāyāna texts like Lotus sutra, such as a concern with preserving texts.[51]

Schopen, Harrison and Nattier also argue that these communities were probably not a single unified movement, but scattered groups based on different practices and sutras.[24] One reason for this view is that Mahāyāna sources are extremely diverse, advocating many different, often conflicting doctrines and positions, as Jan Nattier writes:[52]

Thus we find one scripture (the Aksobhya-vyuha) that advocates both srávaka and bodhisattva practices, propounds the possibility of rebirth in a pure land, and enthusiastically recommends the cult of the book, yet seems to know nothing of emptiness theory, the ten bhumis, or the trikaya, while another (the P’u-sa pen-yeh ching) propounds the ten bhumis and focuses exclusively on the path of the bodhisattva, but never discusses the paramitas. A Madhyamika treatise (Nagarjuna's Mulamadhyamika-karikas) may enthusiastically deploy the rhetoric of emptiness without ever mentioning the bodhisattva path, while a Yogacara treatise (Vasubandhu's Madhyanta-vibhaga-bhasya) may delve into the particulars of the trikaya doctrine while eschewing the doctrine of ekayana. We must be prepared, in other words, to encounter a multiplicity of Mahayanas flourishing even in India, not to mention those that developed in East Asia and Tibet.

In spite of being a minority in India, Indian Mahāyāna was an intellectually vibrant movement, which developed various schools of thought during what Jan Westerhoff has been called "The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy" (from the beginning of the first millennium CE up to the 7th century).[53] Some major Mahāyāna traditions are Prajñāpāramitā, Mādhyamaka, Yogācāra, Buddha-nature (Tathāgatagarbha), and the school of Dignaga and Dharmakirti as the last and most recent.[54] Major early figures include Nagarjuna, Āryadeva, Aśvaghoṣa, Asanga, Vasubandhu, and Dignaga. Mahāyāna Buddhists seem to have been active in the Kushan Empire (30–375 CE), a period that saw great missionary and literary activities by Buddhists. This is supported by the works of the historian Taranatha.[55]

Growth

The Mahāyāna movement (or movements) remained quite small until it experienced much growth in the fifth century. Very few manuscripts have been found before the fifth century (the exceptions are from Bamiyan). According to Walser, "the fifth and sixth centuries appear to have been a watershed for the production of Mahāyāna manuscripts."[57] Likewise it is only in the 4th and 5th centuries CE that epigraphic evidence shows some kind of popular support for Mahāyāna, including some possible royal support at the kingdom of Shan shan as well as in Bamiyan and Mathura.[58]

Still, even after the 5th century, the epigraphic evidence which uses the term Mahāyāna is still quite small and is notably mainly monastic, not lay.[58] By this time, Chinese pilgrims, such as Faxian (337–422 CE), Xuanzang (602–664), Yijing (635–713 CE) were traveling to India, and their writings do describe monasteries which they label 'Mahāyāna' as well as monasteries where both Mahāyāna monks and non-Mahāyāna monks lived together.[59]

After the fifth century, Mahāyāna Buddhism and its institutions slowly grew in influence. Some of the most influential institutions became massive monastic university complexes such as Nalanda (established by the 5th-century CE Gupta emperor, Kumaragupta I) and Vikramashila (established under Dharmapala c. 783 to 820) which were centers of various branches of scholarship, including Mahāyāna philosophy. The Nalanda complex eventually became the largest and most influential Buddhist center in India for centuries.[60] Even so, as noted by Paul Williams, "it seems that fewer than 50 percent of the monks encountered by Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang; c. 600–664) on his visit to India actually were Mahāyānists."[61]

Expansion outside of India

Over time Indian Mahāyāna texts and philosophy reached Central Asia and China through trade routes like the Silk Road, later spreading throughout East Asia. Over time, Central Asian Buddhism became heavily influenced by Mahāyāna and it was a major source for Chinese Buddhism. Mahāyāna works have also been found in Gandhāra, indicating the importance of this region for the spread of Mahāyāna. Central Asian Mahāyāna scholars were very important in the Silk Road Transmission of Buddhism.[62] They include translators like Lokakṣema (c. 167–186), Dharmarakṣa (c. 265–313), Kumārajīva (c. 401), and Dharmakṣema (385–433). The site of Dunhuang seems to have been a particularly important place for the study of Mahāyāna Buddhism.[55]

By the fourth century, Chinese monks like Faxian (c. 337–422 CE) had also begun to travel to India (now dominated by the Guptas) to bring back Buddhist teachings, especially Mahāyāna works.[63] These figures also wrote about their experiences in India and their work remains invaluable for understanding Indian Buddhism. In some cases Indian Mahāyāna traditions were directly transplanted, as with the case of the East Asian Madhymaka (by Kumārajīva) and East Asian Yogacara (especially by Xuanzang). Later, new developments in Chinese Mahāyāna led to new Chinese Buddhist traditions like Tiantai, Huayen, Pure Land and Chan Buddhism (Zen). These traditions would then spread to Korea, Vietnam and Japan.

Forms of Mahāyāna Buddhism which are mainly based on the doctrines of Indian Mahāyāna sutras are still popular in East Asian Buddhism, which is mostly dominated by various branches of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Paul Williams has noted that in this tradition in the Far East, primacy has always been given to the study of the Mahāyāna sūtras.[64]

Later developments

Beginning during the Gupta (c. 3rd century CE–575 CE) period a new movement began to develop which drew on previous Mahāyāna doctrine as well as new Pan-Indian tantric ideas. This came to be known by various names such as Vajrayāna (Tibetan: rdo rje theg pa), Mantrayāna, and Esoteric Buddhism or "Secret Mantra" (Guhyamantra). This new movement continued into the Pala era (8th century–12th century CE), during which it grew to dominate Indian Buddhism.[65] Possibly led by groups of wandering tantric yogis named mahasiddhas, this movement developed new tantric spiritual practices and also promoted new texts called the Buddhist Tantras.[66] Philosophically, Vajrayāna Buddhist thought remained grounded in the Mahāyāna Buddhist ideas of Madhyamaka, Yogacara and Buddha-nature.[67][68] Tantric Buddhism generally deals with new forms of meditation and ritual which often makes use of the visualization of Buddhist deities (including Buddhas, bodhisattvas, dakinis, and fierce deities) and the use of mantras. Most of these practices are esoteric and require ritual initiation or introduction by a tantric master (vajracarya) or guru.[69]

The source and early origins of Vajrayāna remain a subject of debate among scholars. Some scholars like Alexis Sanderson argue that Vajrayāna derives its tantric content from Shaivism and that it developed as a result of royal courts sponsoring both Buddhism and Saivism. Sanderson argues that Vajrayāna works like the Samvara and Guhyasamaja texts show direct borrowing from Shaiva tantric literature.[70][71] However, other scholars such as Ronald M. Davidson question the idea that Indian tantrism developed in Shaivism first and that it was then adopted into Buddhism. Davidson points to the difficulties of establishing a chronology for the Shaiva tantric literature and argues that both traditions developed side by side, drawing on each other as well as on local Indian tribal religion.[72]

Whatever the case, this new tantric form of Mahāyāna Buddhism became extremely influential in India, especially in Kashmir and in the lands of the Pala Empire. It eventually also spread north into Central Asia, the Tibetan plateau and to East Asia. Vajrayāna remains the dominant form of Buddhism in Tibet, in surrounding regions like Bhutan and in Mongolia. Esoteric elements are also an important part of East Asian Buddhism where it is referred to by various terms. These include: Zhēnyán (Chinese: 真言, literally "true word", referring to mantra), Mìjiao (Chinese: 密教; Esoteric Teaching), Mìzōng (密宗; "Esoteric Tradition") or Tángmì (唐密; "Tang (Dynasty) Esoterica") in Chinese and Shingon, Tomitsu, Mikkyo, and Taimitsu in Japanese.

Worldview

_LACMA_M.81.90.6_(3_of_6).jpg.webp)

Few things can be said with certainty about Mahāyāna Buddhism in general other than that the Buddhism practiced in China, Indonesia, Vietnam, Korea, Tibet, Mongolia and Japan is Mahāyāna Buddhism.[note 8] Mahāyāna can be described as a loosely bound collection of many teachings and practices (some of which are seemingly contradictory).[note 9] Mahāyāna constitutes an inclusive and broad set of traditions characterized by plurality and the adoption of a vast number of new sutras, ideas and philosophical treatises in addition to the earlier Buddhist texts.

Broadly speaking, Mahāyāna Buddhists accept the classic Buddhist doctrines found in early Buddhism (i.e. the Nikāya and Āgamas), such as the Middle Way, Dependent origination, the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, the Three Jewels, the Three marks of existence and the bodhipakṣadharmas (aids to awakening).[73] Mahāyāna Buddhism further accepts some of the ideas found in Buddhist Abhidharma thought. However, Mahāyāna also adds numerous Mahāyāna texts and doctrines, which are seen as definitive and in some cases superior teachings.[74][75] D.T. Suzuki described the broad range and doctrinal liberality of Mahāyāna as "a vast ocean where all kinds of living beings are allowed to thrive in a most generous manner, almost verging on a chaos."[76]

Paul Williams refers to the main impulse behind Mahāyāna as the vision which sees the motivation to achieve Buddhahood for sake of other beings as being the supreme religious motivation. This is way that Atisha defines Mahāyāna in his Bodhipathapradipa.[77] As such, according to Williams, "Mahāyāna is not as such an institutional identity. Rather, it is inner motivation and vision, and this inner vision can be found in anyone regardless of their institutional position."[78] Thus, instead of a specific school or sect, Mahāyāna is a "family term" or a religious tendency, which is united by "a vision of the ultimate goal of attaining full Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings (the 'bodhisattva ideal') and also (or eventually) a belief that Buddhas are still around and can be contacted (hence the possibility of an ongoing revelation)."[79]

The Buddhas

Buddhas and bodhisattvas (beings on their way to Buddhahood) are central elements of Mahāyāna. Mahāyāna has a vastly expanded cosmology and theology, with various Buddhas and powerful bodhisattvas residing in different worlds and buddha-fields (buddha kshetra).[5] Buddhas unique to Mahāyāna include the Buddhas Amitābha ("Infinite Light"), Akṣobhya ("the Imperturbable"), Bhaiṣajyaguru ("Medicine guru") and Vairocana ("the Illuminator"). In Mahāyāna, a Buddha is seen as a being that has achieved the highest kind of awakening due to his superior compassion and wish to help all beings.[80]

An important feature of Mahāyāna is the way that it understands the nature of a Buddha, which differs from non-Mahāyāna understandings. Mahāyāna texts not only often depict numerous Buddhas besides Sakyamuni, but see them as transcendental or supramundane (lokuttara) beings with great powers and huge lifetimes. The White Lotus Sutra famously describes the lifespan of the Buddha as immeasurable and states that he actually achieved Buddhahood countless of eons (kalpas) ago and has been teaching the Dharma through his numerous avatars for an unimaginable period of time.[81][82][83]

Furthermore, Buddhas are active in the world, constantly devising ways to teach and help all sentient beings. According to Paul Williams, in Mahāyāna, a Buddha is often seen as "a spiritual king, relating to and caring for the world", rather than simply a teacher who after his death "has completely 'gone beyond' the world and its cares".[84] Buddha Sakyamuni's life and death on earth are then usually understood docetically as a "mere appearance", his death is a show, while in actuality he remains out of compassion to help all sentient beings.[84] Similarly, Guang Xing describes the Buddha in Mahāyāna as an omnipotent and almighty divinity "endowed with numerous supernatural attributes and qualities."[85]

The idea that Buddhas remain accessible is extremely influential in Mahāyāna and also allows for the possibility of having a reciprocal relationship with a Buddha through prayer, visions, devotion and revelations.[86] Through the use of various practices, a Mahāyāna devotee can aspire to be reborn in a Buddha's pure land or buddha field (buddhakṣetra), where they can strive towards Buddhahood in the best possible conditions. Depending on the sect, liberation into a buddha-field can be obtained by faith, meditation, or sometimes even by the repetition of Buddha's name. Faith-based devotional practices focused on rebirth in pure lands are common in East Asia Pure Land Buddhism.[87]

The influential Mahāyāna concept of the three bodies (trikāya) of a Buddha developed to make sense of the transcendental nature of the Buddha. This doctrine holds that the "bodies of magical transformation" (nirmāṇakāyas) and the "enjoyment bodies" (saṃbhogakāya) are emanations from the ultimate Buddha body, the Dharmakaya, which is none other than the ultimate reality itself, i.e. emptiness or Thusness.[88]

The Bodhisattvas

The Mahāyāna bodhisattva path (mārga) or vehicle (yāna) is seen as being the superior spiritual path by Mahāyānists, over and above the paths of those who seek arhatship or "solitary buddhahood" for their own sake (Śrāvakayāna and Pratyekabuddhayāna).[89] Mahāyāna Buddhists generally hold that pursuing only the personal release from suffering i.e. nirvāṇa is a smaller or inferior aspiration (called "hinayana"), because it lacks the wish and resolve to liberate all other sentient beings from saṃsāra (the round of rebirth) by becoming a Buddha.[90][91][92]

This wish to help others is called bodhicitta. One who engages in this path to complete buddhahood is called a bodhisattva. High level bodhisattvas are seen as extremely powerful supramundane beings which are objects of devotion and prayer throughout Mahāyāna lands.[93] Popular bodhisattvas which are revered across Mahāyāna include Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, Tara and Maitreya. Bodhisattvas could reach the personal nirvana of the arhats, but they reject this goal and remain in saṃsāra to help others out of compassion.[94][95][93]

According to eighth-century Mahāyāna philosopher Haribhadra, the term "bodhisattva" can technically refer to those who follow any of the three vehicles, since all are working towards bodhi (awakening) and hence the technical term for a Mahāyāna bodhisattva is a mahāsattva (great being) bodhisattva.[96] According to Paul Williams, a Mahāyāna bodhisattva is best defined as:

that being who has taken the vow to be reborn, no matter how many times this may be necessary, in order to attain the highest possible goal, that of Complete and Perfect Buddhahood. This is for the benefit of all sentient beings.[96]

There are two models for the nature of the bodhisattvas, which are seen in the various Mahāyāna texts. One is the idea that a bodhisattva must postpone their awakening until Buddhahood is attained. This could take eons and in the meantime, they will help countless beings. After reaching Buddhahood, they do pass on to nirvāṇa. The second model is the idea that there are two kinds of nirvāṇa, the nirvāṇa of an arhat and a superior type of nirvāṇa called apratiṣṭhita (non-abiding, not-established) that allows a Buddha to remain forever engaged in the world. As noted by Paul Williams, the idea of apratiṣṭhita nirvāṇa may have taken some time to develop and is not obvious in some of the early Mahāyāna literature.[95]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The Bodhisattva Path

In most classic Mahāyāna sources (as well as in non-Mahāyāna sources on the topic), the bodhisattva path is said to take three or four asaṃkheyyas ("incalculable eons"), requiring a huge number of lifetimes of practice.[98][99] However, certain practices are sometimes held to provide shortcuts to Buddhahood (these vary widely by tradition). According to the Bodhipathapradīpa (A Lamp for the Path to Awakening) by the Indian master Atiśa, the central defining feature of a bodhisattva's path is the universal aspiration to end suffering for themselves and all other beings, i.e. bodhicitta.[100]

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhist philosophy |

|---|

|

|

|

The bodhisattva's spiritual path is traditionally held to begin with the revolutionary event called the "arising of the Awakening Mind" (bodhicittotpāda), which is the wish to become a Buddha in order to help all beings.[99] This is achieved in different ways, such as the meditation taught by the Indian master Shantideva in his Bodhicaryavatara called "equalising self and others and exchanging self and others." Other Indian masters like Atisha and Kamalashila also teach a meditation in which we contemplate how all beings have been our close relatives or friends in past lives. This contemplation leads to the arising of deep love (maitrī) and compassion (karuṇā) for others, and thus bodhicitta is generated.[101] According to the Indian philosopher Shantideva, when great compassion and bodhicitta arises in a person's heart, they cease to be an ordinary person and become a "son or daughter of the Buddhas".[100]

The idea of the bodhisattva is not unique to Mahāyāna Buddhism and it is found in Theravada and other early Buddhist schools. However, these schools held that becoming a bodhisattva required a prediction of one's future Buddhahood in the presence of a living Buddha.[102] In Mahāyāna a bodhisattva is applicable to any person from the moment they intend to become a Buddha (i.e. the arising of bodhicitta) and without the requirement of a living Buddha.[102] Some Mahāyāna sūtras like the Lotus Sutra, promote the bodhisattva path as being universal and open to everyone. Other texts disagree with this.[103]

The generation of bodhicitta may then be followed by the taking of the bodhisattva vows to "lead to Nirvana the whole immeasurable world of beings" as the Prajñaparamita sutras state. This compassionate commitment to help others is the central characteristic of the Mahāyāna bodhisattva.[104] These vows may be accompanied by certain ethical guidelines or bodhisattva precepts. Numerous sutras also state that a key part of the bodhisattva path is the practice of a set of virtues called pāramitās (transcendent or supreme virtues). Sometimes six are outlined: giving, ethical discipline, patient endurance, diligence, meditation and transcendent wisdom.[105][5] Other sutras (like the Daśabhūmika) give a list of ten, with the addition of upāya (skillful means), praṇidhāna (vow, resolution), Bala (spiritual power) and Jñāna (knowledge).[106] Prajñā (transcendent knowledge or wisdom) is arguably the most important virtue of the bodhisattva. This refers to an understanding of the emptiness of all phenomena, arising from study, deep consideration and meditation.[104]

Bodhisattva levels

Various texts associate the beginning of the bodhisattva practice with what is called the "path of accumulation" or equipment (saṃbhāra-mārga), which is the first path of the classic five paths schema.[107]

The Daśabhūmika Sūtra as well as other texts also outline a series of bodhisattva levels or spiritual stages (bhūmis ) on the path to Buddhahood. The various texts disagree on the number of stages however, the Daśabhūmika giving ten for example (and mapping each one to the ten paramitas), the Bodhisattvabhūmi giving seven and thirteen and the Avatamsaka outlining 40 stages.[106]

In later Mahāyāna scholasticism, such as in the work of Kamalashila and Atiśa, the five paths and ten bhūmi systems are merged and this is the progressive path model that is used in Tibetan Buddhism. According to Paul Williams, in these systems, the first bhūmi is reached once one attains "direct, nonconceptual and nondual insight into emptiness in meditative absorption", which is associated with the path of seeing (darśana-mārga).[107] At this point, a bodhisattva is considered an ārya (a noble being).[108]

Skillful means and the One Vehicle

Skillful means or Expedient techniques (Skt. upāya) is another important virtue and doctrine in Mahāyāna Buddhism.[109] The idea is most famously expounded in the White Lotus Sutra, and refers to any effective method or technique that is conducive to spiritual growth and leads beings to awakening and nirvana. This doctrine states that the Buddha adapts his teaching to whoever he is teaching to out of compassion. Because of this, it is possible that the Buddha may teach seemingly contradictory things to different people. This idea is also used to explain the vast textual corpus found in Mahāyāna.[110]

A closely related teaching is the doctrine of the One Vehicle (ekayāna). This teaching states that even though the Buddha is said to have taught three vehicles (the disciples' vehicle, the vehicle of solitary Buddhas and the bodhisattva vehicle, which are accepted by all early Buddhist schools), these actually are all skillful means which lead to the same place: Buddhahood. Therefore, there really are not three vehicles in an ultimate sense, but one vehicle, the supreme vehicle of the Buddhas, which is taught in different ways depending on the faculties of individuals. Even those beings who think they have finished the path (i.e. the arhats) are actually not done, and they will eventually reach Buddhahood.[110]

This doctrine was not accepted in full by all Mahāyāna traditions. The Yogācāra school famously defended an alternative theory that held that not all beings could become Buddhas. This became a subject of much debate throughout Mahāyāna Buddhist history.[111]

Prajñāpāramitā (Transcendent Knowledge)

Some of the key Mahāyāna teachings are found in the Prajñāpāramitā ("Transcendent Knowledge" or "Perfection of Wisdom") texts, which are some of the earliest Mahāyāna works.[112] Prajñāpāramitā is a deep knowledge of reality which Buddhas and bodhisattvas attain. It is a transcendent, non-conceptual and non-dual kind of knowledge into the true nature of things.[113] This wisdom is also associated with insight into the emptiness (śūnyatā) of dharmas (phenomena) and their illusory nature (māyā).[114] This amounts to the idea that all phenomena (dharmas) without exception have "no essential unchanging core" (i.e. they lack svabhāva, an essence or inherent nature), and therefore have "no fundamentally real existence."[115] These empty phenomena are also said to be conceptual constructions.[116]

Because of this, all dharmas (things, phenomena), even the Buddha's Teaching, the Buddha himself, Nirvāṇa and all living beings, are like "illusions" or "magic" (māyā) and "dreams" (svapna).[117][116] This emptiness or lack of real existence applies even to the apparent arising and ceasing of phenomena. Because of this, all phenomena are also described as unarisen (anutpāda), unborn (ajata), "beyond coming and going" in the Prajñāpāramitā literature.[118][119] Most famously, the Heart Sutra states that "all phenomena are empty, that is, without characteristic, unproduced, unceased, stainless, not stainless, undiminished, unfilled."[120] The Prajñāpāramitā texts also use various metaphors to describe the nature of things, for example, the Diamond Sutra compares phenomena to: "A shooting star, a clouding of the sight, a lamp, an illusion, a drop of dew, a bubble, a dream, a lightning's flash, a thunder cloud."[121]

Prajñāpāramitā is also associated with not grasping, not taking a stand on or "not taking up" (aparigṛhīta) anything in the world. The Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra explains it as "not grasping at form, not grasping at sensation, perception, volitions and cognition."[122] This includes not grasping or taking up even correct Buddhist ideas or mental signs (such as "not-self", "emptiness", bodhicitta, vows), since these things are ultimately all empty concepts as well.[123][116]

Attaining a state of fearless receptivity (ksanti) through the insight into the true nature of reality (Dharmatā) in an intuitive, non-conceptual manner is said to be the prajñāpāramitā, the highest spiritual wisdom. According to Edward Conze, the "patient acceptance of the non-arising of dharmas" (anutpattika-dharmakshanti) is "one of the most distinctive virtues of the Mahāyānistic saint."[124] The Prajñāpāramitā texts also claim that this training is not just for Mahāyānists, but for all Buddhists following any of the three vehicles.[125]

Madhyamaka (Centrism)

The Mahāyāna philosophical school termed Madhyamaka (Middle theory or Centrism, also known as śūnyavāda, 'the emptiness theory') was founded by the second-century figure of Nagarjuna. This philosophical tradition focuses on refuting all theories which posit any kind of substance, inherent existence or intrinsic nature (svabhāva).[127]

In his writings, Nagarjuna attempts to show that any theory of intrinsic nature is contradicted by the Buddha's theory of dependent origination, since anything that has an independent existence cannot be dependently originated. The śūnyavāda philosophers were adamant that their denial of svabhāva is not a kind of nihilism (against protestations to the contrary by their opponents).[128]

Using the two truths theory, Madhyamaka claims that while one can speak of things existing in a conventional, relative sense, they do not exist inherently in an ultimate sense. Madhyamaka also argues that emptiness itself is also "empty", it does not have an absolute inherent existence of its own. It is also not to be understood as a transcendental absolute reality. Instead, the emptiness theory is merely a useful concept that should not be clung to. In fact, for Madhyamaka, since everything is empty of true existence, all things are just conceptualizations (prajñapti-matra), including the theory of emptiness, and all concepts must ultimately be abandoned in order to truly understand the nature of things.[128]

Vijñānavāda (The Consciousness doctrine)

Vijñānavāda ("the doctrine of consciousness", a.k.a. vijñapti-mātra, "perceptions only" and citta-mātra "mind only") is another important doctrine promoted by some Mahāyāna sutras which later became the central theory of a major philosophical movement which arose during the Gupta period called Yogācāra. The primary sutra associated with this school of thought is the Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra, which claims that śūnyavāda is not the final definitive teaching (nītārtha) of the Buddha. Instead, the ultimate truth (paramārtha-satya) is said to be the view that all things (dharmas) are only mind (citta), consciousness (vijñāna) or perceptions (vijñapti) and that seemingly "external" objects (or "internal" subjects) do not really exist apart from the dependently originated flow of mental experiences.[129]

When this flow of mentality is seen as being empty of the subject-object duality we impose upon it, one reaches the non-dual cognition of "Thusness" (tathatā), which is nirvana. This doctrine is developed through various theories, the most important being the eight consciousnesses and the three natures.[130] The Saṃdhinirmocana calls its doctrine the 'third turning of the dharma wheel'. The Pratyutpanna sutra also mentions this doctrine, stating: "whatever belongs to this triple world is nothing but thought [citta-mātra]. Why is that? It is because however I imagine things, that is how they appear".[130]

The most influential thinkers in this tradition were the Indian brothers Asanga and Vasubandhu, along with an obscure figure termed Maitreyanātha. Yogācāra philosophers developed their own interpretation of the doctrine of emptiness which also criticized Madhyamaka for falling into nihilism.[131]

Buddha-nature

_in_flame_type%252C_gilt_bronze_-_Tokyo_National_Museum_-_DSC05173.JPG.webp)

The doctrine of Tathāgata embryo or Tathāgata womb (Tathāgatagarbha), also known as Buddha-nature, matrix or principle (Skt: Buddha-dhātu) is important in all modern Mahāyāna traditions, though it is interpreted in many different ways. Broadly speaking, Buddha-nature is concerned with explaining what allows sentient beings to become Buddhas.[132] The earliest sources for this idea may include the Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra and the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra.[133][132] The Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa refers to "a sacred nature that is the basis for [beings] becoming buddhas",[134] and it also describes it as the 'Self' (atman).[135]

David Seyfort Ruegg explains this concept as the base or support for the practice of the path, and thus it is the "cause" (hetu) for the fruit of Buddhahood.[132] The Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra states that within the defilements is found "the tathagata's wisdom, the tathagata's vision, and the tathagata's body...eternally unsullied, and...replete with virtues no different from my own...the tathagatagarbhas of all beings are eternal and unchanging".[136]

The ideas found in the Buddha-nature literature are a source of much debate and disagreement among Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophers as well as modern academics.[137] Some scholars have seen this as an influence from Brahmanic Hinduism, and some of these sutras admit that the use of the term 'Self' is partly done in order to win over non-Buddhist ascetics (in other words, it is a skillful means).[138][139] According to some scholars, the Buddha-nature discussed in some Mahāyāna sūtras does not represent a substantial self (ātman) which the Buddha critiqued; rather, it is a positive expression of emptiness (śūnyatā) and represents the potentiality to realize Buddhahood through Buddhist practices.[140] Similarly, Williams thinks that this doctrine was not originally dealing with ontological issues, but with "religious issues of realising one's spiritual potential, exhortation, and encouragement."[136]

The Buddha-nature genre of sūtras can be seen as an attempt to state Buddhist teachings using positive language while also maintaining the middle way, to prevent people from being turned away from Buddhism by a false impression of nihilism.[141] This is the position taken by the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, which states that the Buddhas teach the doctrine of tathāgatagarbha (which sounds similar to an atman) in order to help those beings who are attached to the idea of anatman. However, the sutra goes on to say that the tathāgatagarbha is empty and is not actually a substantial self.[142][143]

A different view is defended by various modern scholars like Michael Zimmermann. This view is the idea that Buddha-nature sutras such as the Mahāparinirvāṇa and the Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra teach an affirmative vision of an eternal, indestructible Buddhic Self.[135] Shenpen Hookham, a western scholar and lama sees Buddha-nature as a True Self that is real and permanent.[144] Similarly, C. D. Sebastian understands the Ratnagotravibhāga's view of this topic as a transcendental self that is "the unique essence of the universe".[145]

Arguments for authenticity

Indian Mahāyāna Buddhists faced various criticisms from non-Mahāyānists regarding the authenticity of their teachings. The main critique they faced was that Mahāyāna teachings had not been taught by the Buddha, but were invented by later figures.[146][147] Numerous Mahāyāna texts discuss this issue and attempt to defend the truth and authenticity of Mahāyāna in various ways.[148]

One idea that Mahāyāna texts put forth is that Mahāyāna teachings were taught later because most people were unable to understand the Mahāyāna sūtras at the time of the Buddha and that people were ready to hear the Mahāyāna only in later times.[149] Certain traditional accounts state that Mahāyāna sutras were hidden away or kept safe by divine beings like Nagas or bodhisattvas until the time came for their dissemination.[150][151]

Similarly, some sources also state that Mahāyāna teachings were revealed by other Buddhas, bodhisattvas and devas to a select number of individuals (often through visions or dreams).[148] Some scholars have seen a connection between this idea and Mahāyāna meditation practices which involve the visualization of Buddhas and their Buddha-lands.[152]

Another argument that Indian Buddhists used in favor of the Mahāyāna is that its teachings are true and lead to awakening since they are in line with the Dharma. Because of this, they can be said to be "well said" (subhasita), and therefore, they can be said to be the word of the Buddha in this sense. This idea that whatever is "well spoken" is the Buddha's word can be traced to the earliest Buddhist texts, but it is interpreted more widely in Mahāyāna.[153] From the Mahāyāna point of view, a teaching is the "word of the Buddha" because it is in accord with the Dharma, not because it was spoken by a specific individual (i.e. Gautama).[154] This idea can be seen in the writings of Shantideva (8th century), who argues that an "inspired utterance" is the Buddha word if it is "connected with the truth", "connected with the Dharma", "brings about renunciation of kleshas, not their increase" and "it shows the laudable qualities of nirvana, not those of samsara."[155]

The modern Japanese Zen Buddhist scholar D. T. Suzuki similarly argued that while the Mahāyāna sūtras may not have been directly taught by the historical Buddha, the "spirit and central ideas" of Mahāyāna derive from the Buddha. According to Suzuki, Mahāyāna evolved and adapted itself to suit the times by developing new teachings and texts, while maintaining the spirit of the Buddha.[156]

Claims of superiority

Mahāyāna often sees itself as penetrating further and more profoundly into the Buddha's Dharma. An Indian commentary on the Mahāyānasaṃgraha, gives a classification of teachings according to the capabilities of the audience:[157]

According to disciples' grades, the Dharma is classified as inferior and superior. For example, the inferior was taught to the merchants Trapuṣa and Ballika because they were ordinary men; the middle was taught to the group of five because they were at the stage of saints; the eightfold Prajñāpāramitās were taught to bodhisattvas, and [the Prajñāpāramitās] are superior in eliminating conceptually imagined forms. - Vivṛtaguhyārthapiṇḍavyākhyā

There is also a tendency in Mahāyāna sūtras to regard adherence to these sūtras as generating spiritual benefits greater than those that arise from being a follower of the non-Mahāyāna approaches. Thus the Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra claims that the Buddha said that devotion to Mahāyāna is inherently superior in its virtues to following the śrāvaka or pratyekabuddha paths.[158]

The commentary on the Abhidharmasamuccaya gives the following seven reasons for the "greatness" of the Mahayana: [159]

- Greatness of support (ālambana): the path of the bodhisatva is supported by the limitless teachings of the Perfection of Wisdom in One Hundred Thousand Verses and other texts;

- Greatness of practice (pratipatti): the comprehensive practice for the benefit of self and others (sva-para-artha);

- Greatness of understanding (jñāna): from understanding the absence of self in persons and phenomena (pudgala-dharma-nairātmya);

- Greatness of energy (vīrya): from devotion to many hundreds of thousands of difficult tasks during three incalculable great aeons (mahākalpa);

- Greatness of resourcefulness (upāyakauśalya): because of not taking a stand in Saṃsāra or Nirvāṇa;

- Greatness of attainment (prāpti): because of the attainment of immeasurable and uncountable powers (bala), confidences (vaiśāradya), and dharmas unique to Buddhas ( āveṇika-buddhadharma);

- Greatness of deeds (karma): because of willing the performance of the deeds of a Buddha until the end of Saṃsāra by displaying awakening, etc.

Practice

Mahāyāna Buddhist practice is quite varied. A common set of virtues and practices which is shared by all Mahāyāna traditions are the six perfections or transcendent virtues (pāramitā).

A central practice advocated by numerous Mahāyāna sources is focused around "the acquisition of merit, the universal currency of the Buddhist world, a vast quantity of which was believed to be necessary for the attainment of Buddhahood".[160]

Another important class of Mahāyāna Buddhist practice is textual practices that deal with listening to, memorizing, reciting, preaching, worshiping and copying Mahāyāna sūtras.[39]

Pāramitā

Mahāyāna sūtras, especially those of the Prajñāpāramitā genre, teach the practice of the six transcendent virtues or perfections (pāramitā) as part of the path to Buddhahood. Special attention is given to transcendent knowledge (prajñāpāramitā), which is seen as a primary virtue.[161] According to Donald S. Lopez Jr., the term pāramitā can mean "excellence" or "perfection" as well as "that which has gone beyond" or "transcendence".[162]

The Prajñapāramitā sūtras, and a large number of other Mahāyāna texts list six perfections:[163][164][160]

- Dāna pāramitā: generosity, charity, giving

- Śīla pāramitā: virtue, discipline, proper conduct (see also: Bodhisattva precepts)

- Kṣānti pāramitā: patience, tolerance, forbearance, acceptance, endurance

- Vīrya pāramitā: energy, diligence, vigour, effort

- Dhyāna pāramitā: one-pointed concentration, contemplation, meditation

- Prajñā pāramitā: transcendent wisdom, spiritual knowledge

This list is also mentioned by the Theravāda commentator Dhammapala, who describes it as a categorization of the same ten perfections of Theravada Buddhism. According to Dhammapala, Sacca is classified as both Śīla and Prajñā, Mettā and Upekkhā are classified as Dhyāna, and Adhiṭṭhāna falls under all six.[164] Bhikkhu Bodhi states that the correlations between the two sets show there was a shared core before the Theravada and Mahayana schools split.[165]

In the Ten Stages Sutra and the Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra, four more pāramitās are listed:[106]

- 7. Upāya pāramitā: skillful means

- 8. Praṇidhāna pāramitā: vow, resolution, aspiration, determination, this related to the bodhisattva vows

- 9. Bala pāramitā: spiritual power

- 10. Jñāna pāramitā: knowledge

Meditation

Mahāyāna Buddhism teaches a vast array of meditation practices. These include meditations which are shared with the early Buddhist traditions, including mindfulness of breathing; mindfulness of the unattractivenes of the body; loving-kindness; the contemplation of dependent origination; and mindfulness of the Buddha.[166][167] In Chinese Buddhism, these five practices are known as the "five methods for stilling or pacifying the mind" and support the development of the stages of dhyana.[168]

The Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra (compiled c. 4th century), which is the most comprehensive Indian treatise on Mahāyāna practice, discusses classic Buddhist numerous meditation methods and topics, including the four dhyānas, the different kinds of samādhi, the development of insight (vipaśyanā) and tranquility (śamatha), the four foundations of mindfulness (smṛtyupasthāna), the five hindrances (nivaraṇa), and classic Buddhist meditations such as the contemplation of unattractiveness, impermanence (anitya), suffering (duḥkha), and contemplation death (maraṇasaṃjñā).[169]

Other works of the Yogācāra school, such as Asaṅga's Abhidharmasamuccaya, and Vasubandhu's Madhyāntavibhāga-bhāsya also discuss meditation topics such as mindfulness, smṛtyupasthāna, the 37 wings to awakening, and samadhi.[170]

A very popular Mahāyāna practice from very early times involved the visualization of a Buddha while practicing mindfulness of a Buddha (buddhānusmṛti) along with their Pure Land. This practice could lead the meditator to feel that they were in the presence of the Buddha and in some cases it was held that it could lead to visions of the Buddhas, through which one could receive teachings from them.[171]

This meditation is taught in numerous Mahāyāna sūtras such as the Pure Land sutras, the Akṣobhya-vyūha and the Pratyutpanna Samādhi.[172][173] The Pratyutpanna states that through mindfulness of the Buddha meditation one may be able to meet this Buddha in a vision or a dream and learn from them.[174]

Similarly, the Samādhirāja Sūtra for states that:[175]

Those who, while walking, sitting, standing, or sleeping, recollect the moon-like Buddha, will always be in Buddha's presence and will attain the vast nirvāṇa. His pure body is the colour of gold, beautiful is the Protector of the World. Whoever visualizes him like this practises the meditation of the bodhisattvas.

In the case of Pure Land Buddhism, it is widely held that the practice of reciting the Buddha's name (called nianfo in Chinese and nembutsu in Japanese) can lead to rebirth in a Buddha's Pure Land, as well as other positive outcomes. In East Asian Buddhism, the most popular Buddha used for this practice is Amitabha.[171][176]

East Asian Mahāyāna Buddhism also developed numerous unique meditation methods, including the Chan (Zen) practices of huatou, koan meditation, and silent illumination (Jp. shikantaza). Tibetan Buddhism also includes numerous unique forms of contemplation, such as tonglen ("sending and receiving") and lojong ("mind training").

There are also numerous meditative practices that are generally considered to be part of a separate category rather than general or mainstream Mahāyāna meditation. These are the various practices associated with Vajrayāna (also termed Mantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Buddhist Tantra, and Esoteric Buddhism). This family of practices, which include such varied forms as Deity Yoga, Dzogchen, Mahamudra, the Six Dharmas of Nāropa, the recitation of mantras and dharanis, and the use of mudras and mandalas, are very important in Tibetan Buddhism as well as in some forms of East Asian Buddhism (like Shingon and Tendai).

Scripture

Mahāyāna Buddhism takes the basic teachings of the Buddha as recorded in early scriptures as the starting point of its teachings, such as those concerning karma and rebirth, anātman, emptiness, dependent origination, and the Four Noble Truths. Mahāyāna Buddhists in East Asia have traditionally studied these teachings in the Āgamas preserved in the Chinese Buddhist canon. "Āgama" is the term used by those traditional Buddhist schools in India who employed Sanskrit for their basic canon. These correspond to the Nikāyas used by the Theravāda school. The surviving Āgamas in Chinese translation belong to at least two schools. Most of the Āgamas were never translated into the Tibetan canon, which according to Hirakawa, only contains a few translations of early sutras corresponding to the Nikāyas or Āgamas.[177] However, these basic doctrines are contained in Tibetan translations of later works such as the Abhidharmakośa and the Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra.

Mahāyāna sutras

In addition to accepting the essential scriptures of the early Buddhist schools as valid, Mahāyāna Buddhism maintains large collections of sūtras that are not recognized as authentic by the modern Theravāda school. The earliest of these sutras do not call themselves 'Mahāyāna', but use the terms vaipulya (extensive) sutras, or gambhira (profound) sutras.[39] These were also not recognized by some individuals in the early Buddhist schools. In other cases, Buddhist communities such as the Mahāsāṃghika school were divided along these doctrinal lines.[146] In Mahāyāna Buddhism, the Mahāyāna sūtras are often given greater authority than the Āgamas. The first of these Mahāyāna-specific writings were written probably around the 1st century BCE or 1st-century CE.[178][179] Some influential Mahāyāna sutras are the Prajñaparamita sutras such as the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, the Lotus Sutra, the Pure Land sutras, the Vimalakirti Sutra, the Golden Light Sutra, the Avatamsaka Sutra, the Sandhinirmocana Sutra and the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras.

According to David Drewes, Mahāyāna sutras contain several elements besides the promotion of the bodhisattva ideal, including "expanded cosmologies and mythical histories, ideas of purelands and great, 'celestial' Buddhas and bodhisattvas, descriptions of powerful new religious practices, new ideas on the nature of the Buddha, and a range of new philosophical perspectives."[39] These texts present stories of revelation in which the Buddha teaches Mahāyāna sutras to certain bodhisattvas who vow to teach and spread these sutras after the Buddha's death.[39] Regarding religious praxis, David Drewes outlines the most commonly promoted practices in Mahāyāna sutras were seen as means to achieve Buddhahood quickly and easily and included "hearing the names of certain Buddhas or bodhisattvas, maintaining Buddhist precepts, and listening to, memorizing, and copying sutras, that they claim can enable rebirth in the pure lands Abhirati and Sukhavati, where it is said to be possible to easily acquire the merit and knowledge necessary to become a Buddha in as little as one lifetime."[39] Another widely recommended practice is anumodana, or rejoicing in the good deeds of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

The practice of meditation and visualization of Buddhas has been seen by some scholars as a possible explanation for the source of certain Mahāyāna sutras which are seen traditionally as direct visionary revelations from the Buddhas in their pure lands. Paul Harrison has also noted the importance of dream revelations in certain Mahāyāna sutras such as the Arya-svapna-nirdesa which lists and interprets 108 dream signs.[180]

As noted by Paul Williams, one feature of Mahāyāna sutras (especially earlier ones) is "the phenomenon of laudatory self-reference – the lengthy praise of the sutra itself, the immense merits to be obtained from treating even a verse of it with reverence, and the nasty penalties which will accrue in accordance with karma to those who denigrate the scripture."[181] Some Mahāyāna sutras also warn against the accusation that they are not the word of the Buddha (buddhavacana), such as the Astasāhasrikā (8,000 verse) Prajñāpāramitā, which states that such claims come from Mara (the evil tempter).[182] Some of these Mahāyāna sutras also warn those who would denigrate Mahāyāna sutras or those who preach it (i.e. the dharmabhanaka) that this action can lead to rebirth in hell.[183]

Another feature of some Mahāyāna sutras, especially later ones, is increasing sectarianism and animosity towards non-Mahāyāna practitioners (sometimes called sravakas, "hearers") which are sometimes depicted as being part of the 'hīnayāna' (the 'inferior way') who refuse to accept the 'superior way' of the Mahāyāna.[91][103] As noted by Paul Williams, earlier Mahāyāna sutras like the Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra and the Ajitasena sutra do not present any antagonism towards the hearers or the ideal of arhatship like later sutras do.[103] Regarding the bodhisattva path, some Mahāyāna sutras promote it as a universal path for everyone, while others like the Ugraparipṛcchā see it as something for a small elite of hardcore ascetics.[103]

In the 4th-century Mahāyāna Abhidharma work Abhidharmasamuccaya, Asaṅga refers to the collection which contains the āgamas as the Śrāvakapiṭaka and associates it with the śrāvakas and pratyekabuddhas.[184] Asaṅga classifies the Mahāyāna sūtras as belonging to the Bodhisattvapiṭaka, which is designated as the collection of teachings for bodhisattvas.[184]

Other literature

Mahāyāna Buddhism also developed a massive commentarial and exegetical literature, many of which are called śāstra (treatises) or vrittis (commentaries). Philosophical texts were also written in verse form (karikās), such as in the case of the famous Mūlamadhyamika-karikā (Root Verses on the Middle Way) by Nagarjuna, the foundational text of Madhyamika philosophy. Numerous later Madhyamika philosophers like Candrakirti wrote commentaries on this work as well as their own verse works.

Mahāyāna Buddhist tradition also relies on numerous non-Mahayana commentaries (śāstra), a very influential one being the Abhidharmakosha of Vasubandhu, which is written from a non-Mahayana Sarvastivada–Sautrantika perspective.

Vasubandhu is also the author of various Mahāyāna Yogacara texts on the philosophical theory known as vijñapti-matra (conscious construction only). The Yogacara school philosopher Asanga is also credited with numerous highly influential commentaries. In East Asia, the Satyasiddhi śāstra was also influential.

Another influential tradition is that of Dignāga's Buddhist logic whose work focused on epistemology. He produced the Pramānasamuccaya, and later Dharmakirti wrote the Pramānavārttikā, which was a commentary and reworking of the Dignaga text.

Later Tibetan and Chinese Buddhists continued the tradition of writing commentaries.

Classifications

Dating back at least to the Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra is a classification of the corpus of Buddhism into three categories, based on ways of understanding the nature of reality, known as the "Three Turnings of the Dharma Wheel". According to this view, there were three such "turnings":[185]

- In the first turning, the Buddha taught the Four Noble Truths at Varanasi for those in the śravaka vehicle. It is described as marvelous and wonderful, but requires interpretation and occasioning controversy.[186] The doctrines of the first turning are exemplified in the Dharmacakra Pravartana Sūtra. This turning represents the earliest phase of the Buddhist teachings and the earliest period in the history of Buddhism.

- In the second turning, the Buddha taught the Mahāyāna teachings to the bodhisattvas, teaching that all phenomena have no-essence, no arising, no passing away, are originally quiescent, and essentially in cessation. This turning is also described as marvelous and wonderful, but requiring interpretation and occasioning controversy.[186] Doctrine of the second turning is established in the Prajñāpāramitā teachings, first put into writing around 100 BCE. In Indian philosophical schools, it is exemplified by the Mādhyamaka school of Nāgārjuna.

- In the third turning, the Buddha taught similar teachings to the second turning, but for everyone in the three vehicles, including all the śravakas, pratyekabuddhas, and bodhisattvas. These were meant to be completely explicit teachings in their entire detail, for which interpretations would not be necessary, and controversy would not occur.[186] These teachings were established by the Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra as early as the 1st or 2nd century CE.[187] In the Indian philosophical schools, the third turning is exemplified by the Yogācāra school of Asaṅga and Vasubandhu.

Some traditions of Tibetan Buddhism consider the teachings of Esoteric Buddhism and Vajrayāna to be the third turning of the Dharma Wheel.[188] Tibetan teachers, particularly of the Gelugpa school, regard the second turning as the highest teaching, because of their particular interpretation of Yogācāra doctrine. The Buddha Nature teachings are normally included in the third turning of the wheel.

The different Chinese Buddhist traditions have different schemes of doctrinal periodization called panjiao which they use to organize the sometimes bewildering array of texts.

Relationship with the early texts

Scholars have noted that many key Mahāyāna ideas are closely connected to the earliest texts of Buddhism. The seminal work of Mahāyāna philosophy, Nāgārjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, mentions the canon's Katyāyana Sūtra (SA 301) by name, and may be an extended commentary on that work.[189] Nāgārjuna systematized the Mādhyamaka school of Mahāyāna philosophy. He may have arrived at his positions from a desire to achieve a consistent exegesis of the Buddha's doctrine as recorded in the canon. In his eyes, the Buddha was not merely a forerunner, but the very founder of the Mādhyamaka system.[190] Nāgārjuna also referred to a passage in the canon regarding "nirvanic consciousness" in two different works.[191]

Yogācāra, the other prominent Mahāyāna school in dialectic with the Mādhyamaka school, gave a special significance to the canon's Lesser Discourse on Emptiness (MA 190).[192] A passage there (which the discourse itself emphasizes) is often quoted in later Yogācāra texts as a true definition of emptiness.[193] According to Walpola Rahula, the thought presented in the Yogācāra school's Abhidharma-samuccaya is undeniably closer to that of the Pali Nikayas than is that of the Theravadin Abhidhamma.[194]

Both the Mādhyamikas and the Yogācārins saw themselves as preserving the Buddhist Middle Way between the extremes of nihilism (everything as unreal) and substantialism (substantial entities existing). The Yogācārins criticized the Mādhyamikas for tending towards nihilism, while the Mādhyamikas criticized the Yogācārins for tending towards substantialism.[195]

Key Mahāyāna texts introducing the concepts of bodhicitta and Buddha nature also use language parallel to passages in the canon containing the Buddha's description of "luminous mind" and appear to have evolved from this idea.[196][197]

Contemporary Mahāyāna Buddhism

The main contemporary traditions of Mahāyāna in Asia are:

- The East Asian Mahāyāna traditions of China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam, also known as "Eastern Buddhism". Peter Harvey estimates that there are about 360 million Eastern Buddhists in Asia.[198]

- The Indo-Tibetan tradition (mainly found in Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, parts of India and Nepal), also known as "Northern Buddhism". According to Harvey "the number of people belonging to Northern Buddhism totals only around 18.2 million."[199]

There are also some minor Mahāyāna traditions practiced by minority groups, such as Newar Buddhism practiced by the Newar people (Nepal) and Azhaliism practiced by the Bai people (Yunnan).

Furthermore, there are also various new religious movements which either see themselves as Mahāyāna or are strongly influenced by Mahāyāna Buddhism. Examples of these include Hòa Hảo, Won Buddhism, Triratna Buddhist Community and Sōka Gakkai.

Lastly, some religious traditions such as Bon and Shugendo are strongly influenced by Mahāyāna Buddhism, though they may not be considered as being "Buddhist" per se.

Most of the major forms of contemporary Mahāyāna Buddhism are also practiced by Asian immigrant populations in the West and also by western convert Buddhists. For more on this topic see: Buddhism in the West.

Chinese

Contemporary Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism (also known as Han Buddhism) is practiced through many varied forms, such as Chan, Pure land, Tiantai, Huayan and mantra practices. This group is the largest population of Buddhists in the world. There are between 228 and 239 million Mahāyāna Buddhists in the People's Republic of China (this does not include the Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhists who practice Tibetan Buddhism).[198]

Harvey also gives the East Asian Mahāyāna Buddhist population in other nations as follows: Taiwanese Buddhists, 8 million; Malaysian Buddhists, 5.5 million; Singaporean Buddhists, 1.5 million; Hong Kong, 0.7 million; Indonesian Buddhists, 4 million, The Philippines: 2.3 million.[198] Most of these are Han Chinese populations.

Chinese Buddhism can be divided into various different traditions (zong), such as Sanlun, Faxiang, Tiantai, Huayan, Pure Land, Chan, and Zhenyan. However, historically, most temples, institutions and Buddhist practitioners usually did not belong to any single "sect" (as is common in Japanese Buddhism), but draw from the various different elements of Chinese Buddhist thought and practice. This non-sectarian and eclectic aspect of Chinese Buddhism as a whole has persisted from its historical beginnings into its modern practice.[200][201] The modern development of an ideaology called Humanistic Buddhism (Chinese: 人間佛教; pinyin: rénjiān fójiào, more literally "Buddhism for the Human World") has also been influential on Chinese Buddhist leaders and institutions.[202] In addition, Chinese Buddhists may also practice some form of religious syncretism with other Chinese religions, such as Taoism.[203] In modern China, the reform and opening up period in the late 20th century saw a particularly significant increase in the number of converts to Chinese Buddhism, a growth which has been called "extraordinary".[204] Outside of mainland China, Chinese Buddhism is also practiced in Taiwan and wherever there are Chinese diaspora communities.

Korean

Korean Buddhism consists mostly of the Korean Seon school (i.e. Zen), primarily represented by the Jogye Order and the Taego Order. Korean Seon also includes some Pure Land practice.[205] It is mainly practiced in South Korea, with a rough population of about 10.9 million Buddhists.[198] There are also some minor schools, such as the Cheontae (i.e. Korean Tiantai), and the esoteric Jingak and Chinŏn schools.

While North Korea's totalitarian government remains repressive and ambivalent towards religion, at least 11 percent of the population is considered to be Buddhist according to Williams.[206]

Japanese

Japanese Buddhism is divided into numerous traditions which include various sects of Pure Land Buddhism, Tendai, Nichiren Buddhism, Shingon and Zen. There are also various Mahāyāna oriented Japanese new religions that arose in the post-war period. Many of these new religions are lay movements like Sōka Gakkai and Agon Shū.[207]

An estimate of the Japanese Mahāyāna Buddhist population is given by Harvey as 52 million and a recent 2018 survey puts the number at 84 million.[198][208] It should also be noted that many Japanese Buddhists also participate in Shinto practices, such as visiting shrines, collecting amulets and attending festivals.[209]

Vietnamese

Vietnamese Buddhism is strongly influenced by the Chinese tradition. It is a synthesis of numerous practices and ideas. Vietnamese Mahāyāna draws practices from Vietnamese Thiền (Chan/Zen), Tịnh độ (Pure Land), and Mật Tông (Mantrayana) and its philosophy from Hoa Nghiêm (Huayan) and Thiên Thai (Tiantai).[210] New Mahāyāna movements have also developed in the modern era, perhaps the most influential of which has been Thích Nhất Hạnh's Plum Village Tradition, which also draws from Theravada Buddhism.

Though Vietnamese Buddhism suffered extensively during the Vietnam war (1955-1975) and during subsequent communist takeover of the south, there has been a revival of the religion since the liberalization period following 1986. There are about 43 million Vietnamese Mahāyāna Buddhists.[198]

Northern Buddhism

Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism or "Northern" Buddhism derives from the Indian Vajrayana Buddhism that was adopted in medieval Tibet. Though it includes numerous tantric Buddhist practices not found in East Asian Mahāyāna, Northern Buddhism still considers itself as part of Mahāyāna Buddhism (albeit as one which also contains a more effective and distinct vehicle or yana).

Contemporary Northern Buddhism is traditionally practiced mainly in the Himalayan regions and in some regions of Central Asia, including:[212]

- The Tibet autonomous region (PRC): 5.4 million

- North and North-east India (Sikkhim, Ladakh, West Bengal, Jammu and Kashmir): 0.4 million

- Pakistan: 0.16 million

- Nepal: 2.9 million

- Bhutan: 0.49 million

- Mongolia: 2.7 million

- Inner Mongolia (PRC): 5 million

- Buryatia, Tuva and Kalmykia (Russian Federation): 0.7 million

As with Eastern Buddhism, the practice of northern Buddhism declined in Tibet, China and Mongolia during the communist takeover of these regions (Mongolia: 1924, Tibet: 1959). Tibetan Buddhism continued to be practiced among the Tibetan diaspora population, as well as by other Himalayan peoples in Bhutan, Ladakh and Nepal. Post-1980s though, Northern Buddhism has seen a revival in both Tibet and Mongolia due to more liberal government policies towards religious freedom.[213] Northern Buddhism is also now practiced in the Western world by western convert Buddhists.

Theravāda school

Role of the Bodhisattva

In the early Buddhist texts, and as taught by the modern Theravada school, the goal of becoming a teaching Buddha in a future life is viewed as the aim of a small group of individuals striving to benefit future generations after the current Buddha's teachings have been lost, but in the current age there is no need for most practitioners to aspire to this goal. Theravada texts do, however, hold that this is a more perfectly virtuous goal.[214]

Paul Williams writes that some modern Theravada meditation masters in Thailand are popularly regarded as bodhisattvas.[215]

Cholvijarn observes that prominent figures associated with the Self perspective in Thailand have often been famous outside scholarly circles as well, among the wider populace, as Buddhist meditation masters and sources of miracles and sacred amulets. Like perhaps some of the early Mahāyāna forest hermit monks, or the later Buddhist Tantrics, they have become people of power through their meditative achievements. They are widely revered, worshipped, and held to be arhats or (note!) bodhisattvas.

Theravāda and Hīnayāna

In the 7th century, the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang describes the concurrent existence of the Mahāvihara and the Abhayagiri Vihara in Sri Lanka. He refers to the monks of the Mahāvihara as the "Hīnayāna Sthaviras" (Theras), and the monks of the Abhayagiri Vihara as the "Mahāyāna Sthaviras".[216] Xuanzang further writes:[217]

The Mahāvihāravāsins reject the Mahāyāna and practice the Hīnayāna, while the Abhayagirivihāravāsins study both Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna teachings and propagate the Tripiṭaka.

The modern Theravāda school is usually described as belonging to Hīnayāna.[218][219][220][221][222] Some authors have argued that it should not be considered such from the Mahāyāna perspective. Their view is based on a different understanding of the concept of Hīnayāna. Rather than regarding the term as referring to any school of Buddhism that has not accepted the Mahāyāna canon and doctrines, such as those pertaining to the role of the bodhisattva,[219][221] these authors argue that the classification of a school as "Hīnayāna" should be crucially dependent on the adherence to a specific phenomenological position. They point out that unlike the now-extinct Sarvāstivāda school, which was the primary object of Mahāyāna criticism, the Theravāda does not claim the existence of independent entities (dharmas); in this it maintains the attitude of early Buddhism.[223][224][225] Adherents of Mahāyāna Buddhism disagreed with the substantialist thought of the Sarvāstivādins and Sautrāntikas, and in emphasizing the doctrine of emptiness, Kalupahana holds that they endeavored to preserve the early teaching.[226] The Theravādins too refuted the Sarvāstivādins and Sautrāntikas (and other schools) on the grounds that their theories were in conflict with the non-substantialism of the canon. The Theravāda arguments are preserved in the Kathāvatthu.[227]

Some contemporary Theravādin figures have indicated a sympathetic stance toward the Mahāyāna philosophy found in texts such as the Heart Sūtra (Skt. Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya) and Nāgārjuna's Fundamental Stanzas on the Middle Way (Skt. Mūlamadhyamakakārikā).[228][229]

See also

- Buddha-nature

- Buddhist holidays

- Creator in Buddhism

- Dzogchen

- Early Buddhist schools

- Faith in Buddhism

- Golden Light Sutra

- History of Buddhism

- Index of Buddhism-related articles

- Lotus Sutra

- Mahayana sutras

- Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra

- Pure land

- Rebirth

- Schools of Buddhism

- Secular Buddhism

- Śūnyatā

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- Tathagatagarbha

- Tendai

- Tibetan Buddhism

- Zen

Notes

- "The Mahayana, 'Great Vehicle' or 'Great Carriage' (for carrying all beings to nirvana), is also, and perhaps more correctly and accurately, known as the Bodhisattvayana, the bodhisattva's vehicle." Warder, A.K. (3rd edn. 1999). Indian Buddhism: p. 338

- Karashima: "I have assumed that, in the earliest stage of the transmission of the Lotus Sūtra, the Middle Indic forn jāṇa or *jāna (Pkt < Skt jñāna, yāna) had stood in these places ... I have assumed, further, that the Mahāyānist terms buddha-yānā ("the Buddha-vehicle"), mahāyāna ("the great vehicle"), hīnayāna ("the inferior vehicle") meant originally buddha-jñāna ("buddha-knowledge"), mahājñāna ("great knowledge") and hīnajñāna ("inferior knowledge")." Karashima, Seishi (2001). Some features of the Language of the Saddharma-puṇḍarīka-sūtra, Indo-Iranian Journal 44: 207–230

- Warder: "The sudden appearance of large numbers of (Mahayana) teachers and texts (in North India in the second century AD) would seem to require some previous preparation and development, and this we can look for in the South." Warder, A.K. (3rd edn. 1999). Indian Buddhism: p. 335.