Malcolm II of Scotland

Malcolm II (Medieval Gaelic: Máel Coluim mac Cináeda; Scottish Gaelic: Maol Chaluim mac Choinnich; c. 954 – 25 November 1034)[3] was King of the Scots from 1005 until his death.[2][4] He was a son of King Kenneth II; but the name of his mother is uncertain. The Prophecy of Berchán says that his mother was a woman of Leinster and refers to him as Forranach, "the Destroyer".[5]. In contrast, Frederic Van Bossen, a historian from the 17th century, who spent many years accessing many private libraries throughout Europe states his mother was Queen Boada, the daughter to Constantine and the granddaughter to an unnamed Prince of Norway.[6][7]

| Malcolm II | |

|---|---|

| King of Scots | |

| Reign | c. 25 March 1005[1] – 25 November 1034 |

| Predecessor | Kenneth III[2] |

| Successor | Duncan I[2] |

| Born | c. 954[2] |

| Died | 25 November 1034 (aged 79/80)[2] Glamis, Scotland |

| Burial | Iona |

| Issue | Bethóc Donada Olith |

| House | Alpin |

| Father | Kenneth II of Scotland[2] |

To the Irish annals which recorded his death, Malcolm was ard rí Alban, High King of Scotland. In the same way that Brian Bóruma, High King of Ireland, was not the only king in Ireland, Malcolm was one of several kings within the geographical boundaries of modern Scotland: his fellow kings included the king of Strathclyde, who ruled much of the south-west, various Norse-Gael kings on the western coast and the Hebrides and, nearest and most dangerous rivals, the kings or mormaers of Moray. To the south, in the Kingdom of England, the earls of Bernicia and Northumbria, whose predecessors as kings of Northumbria had once ruled most of southern Scotland, still controlled large parts of the southeast.[8]

Early years

Malcolm II was born to Kenneth II of Scotland.[2] He was grandson of Malcolm I of Scotland.[2] In 997, the killer of Constantine is credited as being Kenneth, son of Malcolm. Since there is no known and relevant Kenneth alive at that time (King Kenneth having died in 995), it is considered an error for either Kenneth III, who succeeded Constantine, or, possibly, Malcolm himself, the son of Kenneth II.[9] Whether Malcolm killed Constantine or not, there is no doubt that in 1005 he killed Constantine's successor Kenneth III in battle at Monzievaird in Strathearn.[10]

John of Fordun writes that Malcolm defeated a Norwegian army "in almost the first days after his coronation", but this is not reported elsewhere. Fordun says that the Bishopric of Mortlach (later moved to Aberdeen) was founded in thanks for this victory over the Norwegians.[11]

Children

Malcolm demonstrated a rare ability to survive among early Scottish kings by reigning for 29 years. He was a clever and ambitious man. Brehon tradition provided that the successor to Malcolm was to be selected by him from among the descendants of King Aedh, with the consent of Malcolm's ministers and of the church. Ostensibly in an attempt to end the devastating feuds in the north of Scotland, but obviously influenced by the Norman feudal model, Malcolm ignored tradition and determined to retain the succession within his own line. But since Malcolm had no son of his own, he undertook to negotiate a series of dynastic marriages of his three daughters to men who might otherwise be his rivals, while securing the loyalty of the principal chiefs, their relatives. First he married his daughter Bethoc to Crinan, Thane of The Isles, head of the house of Atholl and secular Abbot of Dunkeld;[2] then his youngest daughter, Olith, to Sigurd, Earl of Orkney. His middle daughter, Donada, was married to Finlay, Earl of Moray, Thane of Ross and Cromarty and a descendant of Loarn of Dalriada. This was risky business under the rules of succession of the Gael, but he thereby secured his rear and, taking advantage of the renewal of Viking attacks on England, marched south to fight the English. He defeated the Angles at Carham in 1018 and installed his grandson, Duncan, son of the Abbot of Dunkeld and his choice as Tanist, in Carlisle as King of Cumbria that same year.[12]

According to Frederic Van Bossen, the wife of Malcolm II was "Gunnora, [the] daughter [of] the second Duke of Normandy".[13] The number of daughters is contested, with Frederic Van Bossen stating he had two daughters (Beatrice who married Albanacht the son of Crinan; and Daboada who was the mother of Macbeth, and the wife of Finell, the Thane of Angus and Glames and the son of Cruthneth.[14] In other sources it is claimed he had 3 daughters:

- Bethóc ingen Maíl Coluim meic Cináeda, married Crínán of Dunkeld, mother of his successor, Duncan I.[2]

- Donalda, married Findláech of Moray, mother of Macbeth, King of Scotland[2]

- Olith, married Sigurd Hlodvirsson, Earl of Orkney, mother of Thorfinn the Mighty

Bernicia

The first reliable report of Malcolm II's reign is of an invasion of Bernicia in 1006, perhaps the customary crech ríg (literally royal prey, a raid by a new king made to demonstrate prowess in war), which involved a siege of Durham. This appears to have resulted in a heavy defeat by the Northumbrians, led by Uhtred of Bamburgh, later Earl of Bernicia, which is reported by the Annals of Ulster.[15]

A second war in Bernicia, probably in 1018, was more successful. The Battle of Carham, by the River Tweed, was a victory for the Scots led by Malcolm II and the men of Strathclyde led by their king, Owen the Bald. By this time Earl Uchtred may have been dead, and Eiríkr Hákonarson was appointed Earl of Northumbria by his brother-in-law Cnut the Great, although his authority seems to have been limited to the south, the former kingdom of Deira, and he took no action against the Scots so far as is known.[16] The work De obsessione Dunelmi (The siege of Durham, associated with Symeon of Durham) claims that Uchtred's brother Eadwulf Cudel surrendered Lothian to Malcolm II, presumably in the aftermath of the defeat at Carham. This is likely to have been the lands between Dunbar and the Tweed as other parts of Lothian had been under Scots control before this time. It has been suggested that Cnut received tribute from the Scots for Lothian, but as he had likely received none from the Bernician Earls this is not very probable.[17]

Cnut

Cnut, reports the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, led an army into Scotland on his return from pilgrimage to Rome. The Chronicle dates this to 1031, but there are reasons to suppose that it should be dated to 1027.[18] Burgundian chronicler Rodulfus Glaber recounts the expedition soon afterwards, describing Malcolm as "powerful in resources and arms … very Christian in faith and deed."[19] Ralph claims that peace was made between Malcolm and Cnut through the intervention of Richard, Duke of Normandy, brother of Cnut's wife Emma. Richard died circa 1027 and Rodulfus wrote close in time to the events.[20]

It has been suggested that the root of the quarrel between Cnut and Malcolm lies in Cnut's pilgrimage to Rome, and the coronation of Holy Roman Emperor Conrad II, where Cnut and Rudolph III, King of Burgundy had the place of honour. If Malcolm were present, and the repeated mentions of his piety in the annals make it quite possible that he made a pilgrimage to Rome, as did Mac Bethad mac Findláich ("Macbeth") in later times, then the coronation would have allowed Malcolm to publicly snub Cnut's claims to overlordship.[21]

Cnut obtained rather less than previous English kings, a promise of peace and friendship rather than the promise of aid on land and sea that Edgar and others had obtained. The sources say that Malcolm was accompanied by one or two other kings, certainly future King Mac Bethad, and perhaps Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, King of Mann and the Isles, and of Galloway.[22] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle remarks of the submission "but he [Malcolm] adhered to that for only a little while".[23] Cnut was soon occupied in Norway against Olaf Haraldsson and appears to have had no further involvement with Scotland.

Orkney and Moray

Olith, a daughter of Malcolm, married Sigurd Hlodvisson, Earl of Orkney.[24] Their son Thorfinn Sigurdsson was said to be five years old when Sigurd was killed on 23 April 1014 in the Battle of Clontarf. The Orkneyinga Saga says that Thorfinn was raised at Malcolm's court and was given the Mormaerdom of Caithness by his grandfather. Thorfinn says in the Heimskringla that he was the ally of the king of Scots, and counted on Malcolm's support to resist the "tyranny" of Norwegian King Olaf Haraldsson.[25] (Thorfinn's older step brother had died while a hostage to King Olaf.) The chronology of Thorfinn's life is problematic, and he may have had a share in the Earldom of Orkney while still a child, if he was indeed only five in 1014.[26] Whatever the exact chronology, before Malcolm's death a client of the king of Scots was in control of Caithness and Orkney, although, as with all such relationships, it is unlikely to have lasted beyond his death.

If Malcolm exercised control over Moray, which is far from being generally accepted, then the annals record a number of events pointing to a struggle for power in the north. In 1020, Mac Bethad's father Findláech mac Ruaidrí was killed by the sons of his brother Máel Brigte.[27] It seems that Máel Coluim mac Máil Brigti took control of Moray, for his death is reported in 1029.[28]

Despite the accounts of the Irish annals, English and Scandinavian writers appear to see Mac Bethad as the rightful king of Moray: this is clear from their descriptions of the meeting with Cnut in 1027, before the death of Malcolm mac Máil Brigti. Malcolm was followed as king or earl by his brother Gillecomgan, husband of Gruoch, a granddaughter of King Kenneth III. It has been supposed that Mac Bethad was responsible for the killing of Gille Coemgáin in 1032, but if Mac Bethad had a cause for feud in the killing of his father in 1020, Malcolm too had reason to see Gille Coemgáin dead. Not only had Gillecomgan's ancestors killed many of Malcolm's kin, but Gillecomgan and his son Lulach might be rivals for the throne. Malcolm had no living sons, and the threat to his plans for the succession was obvious. As a result, the following year Gruoch's brother or nephew, who might have eventually become king, was killed by Malcolm.[29]

Strathclyde and the succession

It has traditionally been supposed that King Owen the Bald of Strathclyde died at the Battle of Carham and that the kingdom passed into the hands of the Scots afterwards. This rests on some very weak evidence. It is far from certain that Owen died at Carham, and it is reasonably certain that there were kings of Strathclyde as late as 1054, when Edward the Confessor sent Earl Siward to install "Malcolm son of the king of the Cumbrians". The confusion is old, probably inspired by William of Malmesbury and embellished by John of Fordun, but there is no firm evidence that the kingdom of Strathclyde was a part of the kingdom of the Scots, rather than a loosely subjected kingdom, before the time of Malcolm II of Scotland's great-grandson Malcolm III.[30]

By the 1030s Malcolm's sons, if he had any, were dead. The only evidence that he did have a son or sons is in Rodulfus Glaber's chronicle where Cnut is said to have stood as godfather to a son of Malcolm.[31] His grandson Thorfinn would have been unlikely to be accepted as king by the Scots, and he chose the sons of his other daughter, Bethóc, who was married to Crínán, lay abbot of Dunkeld, and perhaps Mormaer of Atholl. It may be no more than coincidence, but in 1027 the Irish annals had reported the burning of Dunkeld, although no mention is made of the circumstances.[32] Malcolm's chosen heir, and the first tánaise ríg certainly known in Scotland, was Duncan.

It is possible that a third daughter of Malcolm married Findláech mac Ruaidrí and that Mac Bethad was thus his grandson, but this rests on relatively weak evidence.[33]

Death and posterity

Malcolm died in 1034,[2] Marianus Scotus giving the date as 25 November 1034. The king lists say that he died at Glamis, variously describing him as a "most glorious" or "most victorious" king. The Annals of Tigernach report that "Malcolm mac Cináeda, king of Scotland, the honour of all the west of Europe, died." The Prophecy of Berchán, perhaps the inspiration for John of Fordun and Andrew of Wyntoun's accounts where Malcolm is killed fighting bandits, says that he died by violence, fighting "the parricides".

Perhaps the most notable feature of Malcolm's death is the account of Marianus, matched by the silence of the Irish annals, which tells us that Duncan I became king and ruled for five years and nine months. Given that his death in 1040 is described as being "at an immature age" in the Annals of Tigernach, he must have been a young man in 1034. The absence of any opposition suggests that Malcolm had dealt thoroughly with any likely opposition in his own lifetime.[34]

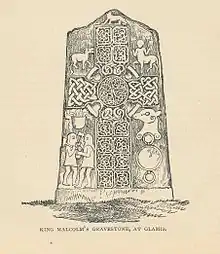

Tradition, dating from Fordun's time if not earlier, knew the Pictish stone now called "Glamis 2" as "King Malcolm's grave stone". The stone is a Class II stone, apparently formed by re-using a Bronze Age standing stone. Its dating is uncertain, with dates from the 8th century onwards having been proposed. While an earlier date is favoured, an association with accounts of Malcolm's has been proposed on the basis of the iconography of the carvings.[35]

On the question of Malcolm's putative pilgrimage, pilgrimages to Rome, or other long-distance journeys, were far from unusual. Thorfinn Sigurdsson, Cnut and Mac Bethad have already been mentioned. Rögnvald Kali Kolsson is known to have gone crusading in the Mediterranean in the 12th century. Nearer in time, Dyfnwal of Strathclyde died on pilgrimage to Rome in 975 as did Máel Ruanaid uá Máele Doraid, King of the Cenél Conaill, in 1025.

Not a great deal is known of Malcolm's activities beyond the wars and killings. The Book of Deer records that Malcolm "gave a king's dues in Biffie and in Pett Meic-Gobraig, and two davochs" to the monastery of Old Deer.[36] He was also probably not the founder of the Bishopric of Mortlach-Aberdeen. John of Fordun has a peculiar tale to tell, related to the supposed "Laws of Malcolm MacKenneth", saying that Malcolm gave away all of Scotland, except for the Moot Hill at Scone, which is unlikely to have any basis in fact.[37]

Notes

- The exact date of succession is unknown, but by tradition it has been stated to be 25 March. (Dunbar, Sir Archibald Hamilton (1906). Scottish Kings: A Revised Chronology of Scottish History, 1005-1625, with Notices of the Principal Events, Tables of Regnal Years, Pedigrees, Tables, Calendars, Etc. D. Douglas. pp. 293.)

- Weir, Alison. Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. p. 179. ISBN 9780099539735.

- Skene, Chronicles, pp. 99–100.

- Malcolm's birth date is not known, but must have been around 980 if the Flateyjarbók is right in dating the marriage of his daughter and Sigurd Hlodvisson to the lifetime of Olaf Tryggvason; Early Sources, p. 528, quoting Olaf Tryggvason's Saga.

- Early Sources, pp. 574–575.

- Derek, Cunningham (2022). The Lost Queens of Scotland: Extracts from Frederic van Bossen’s The Royal Cedar. p. 97.

- van Bossen, Frederic (1688). The Royall Cedar. pp. 71–73.

- Higham, pp. 226–227, notes that the kings of the English had neither lands nor mints north of the Tees.

- Early Sources, pp. 517–518. John of Fordun has Malcolm as the killer; Duncan, p. 46, credits Kenneth MacDuff with the death of Constantine.

- Chronicon Scotorum, s.a. 1005; Early Sources, pp. 521–524; Fordun, IV, xxxviii. Berchán places Cináed's death by the Earn.

- Early Sources, p. 525, note 1; Fordun, IV, xxxix–xl.

- 1. BETHOC [Beatrix Beatrice Betoch] "Genealogy of King William the Lyon" dated 1175 names "Betoch filii Malcolmi" as parent of "Malcolmi filii Dunecani". The Chronicle of the Scots and Picts dated 1177 names "Cran Abbatis de Dunkelden et Bethok filia Malcolm mac Kynnet" as parents of King Duncan. source Beatrice who married Crynyne Abthane of Dul and Steward of the Isles 2. DONALDA [Dovada Duada Doada Donalda] R alph Holinshed's 1577 Chronicle of Scotland names "Doada" as second daughter of Malcolm II King of Scotland and adds that she married "Sinell the thane of Glammis, by whom she had issue one Makbeth". 3. OLITH [Alice Olith Anlite] Orkneyinga Saga records that "Earl Sigurd" married "the daughter of Malcolm King of Scots". Snorre records the marriage of "Sigurd the Thick" and "a daughter of the Scottish king Malcolm". Ulster journal of archaeology, Volume 6 By Ulster Archaeological Society names her as (Alice) wife of Sygurt and daughter of Malcolm II. The American historical magazine, Volume 2 By Publishing Society of New York, Americana Society pg 529 names her Olith or Alice.

- Derek, Cunningham (2022). The Lost Queens of Scotland: Extracts from Frederic van Bossen’s The Royal Cedar. p. 99.

- Cunningham, Derek (2022). The Lost Queens of Scotland: Extracts from Frederic van Bossen’s The Royal Cedar. p. 99.

- Duncan, pp. 27–28; Smyth, pp. 236–237; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 1006.

- Duncan, pp. 28–29 suggests that Earl Uchtred may not have died until 1018. Fletcher accepts that he died in Spring 1016 and the Eadwulf Cudel was Earl of Bernicia when Carham was fought in 1018; Higham, pp. 225–230, agrees. Smyth, pp. 236–237 reserves judgement as to the date of the battle, 1016 or 1018, and whether Uchtred was still living when it was fought. See also Stenton, pp. 418–419 and Daly pp. 53-57.

- Early Sources, p. 544, note 6; Higham, pp. 226–227.

- ASC, Ms D, E and F; Duncan, pp. 29–30.

- Early Sources, pp. 545–546.

- Ralph was writing in 1030 or 1031; Duncan, p. 31.

- Duncan, pp. 31–32; the alternative, he notes, that Cnut was concerned about support for Olaf Haraldsson, "is no better evidenced."

- Duncan, pp. 29–30. St. Olaf's Saga, c. 131 says "two kings came south from Fife in Scotland" to meet Cnut, suggesting only Malcolm and Mac Bethad, and that Cnut returned their lands and gave them gifts. That Echmarcach was king of Galloway is perhaps doubtful; the Annals of Ulster record the death of Suibne mac Cináeda, rí Gall-Gáedel ("King of Galloway") by Tigernach, in 1034.

- ASC, Ms. D, s.a. 1031.

- Early Sources, p. 528; Orkneyinga Saga, c. 12.

- Orkneyinga Saga, cc. 13–20 & 32; St. Olaf's Saga, c. 96.

- Duncan, p.42; reconciling the various dates of Thorfinn's life appears impossible on the face of it. Either he was born well before 1009 and must have died long before 1065, or the accounts in the Orkneyinga Saga are deeply flawed.

- Annals of Tigernach, s.a. 1020; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 1020, but the killers are not named. The Annals of Ulster and the Book of Leinster call Findláech "king of Scotland".

- Annals of Ulster and Annals of Tigernach, s.a. 1029. Malcolm's death is not said to have been by violence and he too is called king rather than mormaer.

- Duncan, pp. 29–30, 32–33 and compare Hudson, Prophecy of Berchán, pp. 222–223. Early Sources, p.571; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 1032 & 1033; Annals of Loch Cé, s.a. 1029 & 1033. The identity of the M. m. Boite killed in 1033 is uncertain, being reading as "the son of the son of Boite" or as "M. son of Boite", Gruoch's brother or nephew respectively.

- Duncan, pp. 29 and 37–41; Oram, David I, pp. 19–21.

- Early Sources, p. 546; Duncan, pp. 30–31, understands Rodulfus Glaber as meaning that Duke Richard was godfather to a son of Cnut and Emma.

- Annals of Ulster and Annals of Loch Cé, s.a. 1027.

- Hudson, pp. 224–225 discusses the question and the reliability of Andrew of Wyntoun's chronicle, on which this rests.

- Duncan, pp. 32–33.

- Laing, Lloyd (2001), "The date and context of the Glamis, Angus, carved Pictish stones" (PDF), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 131: 223–239, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2009

- Gaelic Notes in the Book of Deer.

- Fordun, IV, xliii and Skene's notes; Duncan, p. 150; Barrow, Kingdom of the Scots, p. 39.

References

For primary sources see also External links below.

- Anderson, Alan Orr, Early Sources of Scottish History A.D. 500–1286, volume 1. Reprinted with corrections. Paul Watkins, Stamford, 1990. ISBN 1-871615-03-8

- Anon., Orkneyinga Saga: The History of the Earls of Orkney, tr. Hermann Pálsson and Paul Edwards. Penguin, London, 1978. ISBN 0-14-044383-5

- Barrow, G.W.S., The Kingdom of the Scots. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2003. ISBN 0-7486-1803-1

- Clarkson, Tim, Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age, Birlinn, Edinburgh, 2014, ISBN 9781906566784

- Daly, Rannoch (2018). Birth of the Border, The Battle of Carham 1018 AD (Alnwick; Wanney Books) ISBN 978-1-9997905-5-4

- Duncan, A.A.M., The Kingship of the Scots 842–1292: Succession and Independence. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2002. ISBN 0-7486-1626-8

- Fletcher, Richard, Bloodfeud: Murder and Revenge in Anglo-Saxon England. Penguin, London, 2002. ISBN 0-14-028692-6

- John of Fordun, Chronicle of the Scottish Nation, ed. William Forbes Skene, tr. Felix J.H. Skene, 2 vols. Reprinted, Llanerch Press, Lampeter, 1993. ISBN 1-897853-05-X

- Higham, N.J., The Kingdom of Northumbria AD 350–1100. Sutton, Stroud, 1993. ISBN 0-86299-730-5

- Hudson, Benjamin T., The Prophecy of Berchán: Irish and Scottish High-Kings of the Early Middle Ages. Greenwood, London, 1996.

- Smyth, Alfred P. Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000. Reprinted, Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 1998. ISBN 0-7486-0100-7

- Stenton, Sir Frank, Anglo-Saxon England. 3rd edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1971 ISBN 0-19-280139-2

- Sturluson, Snorri, Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway, tr. Lee M. Hollander. Reprinted University of Texas Press, Austin, 1992. ISBN 0-292-73061-6

External links

- CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts at University College Cork includes the Annals of Ulster, Tigernach, the Four Masters and Innisfallen, the Chronicon Scotorum, the Lebor Bretnach (which includes the Duan Albanach), Genealogies, and various Saints' Lives. Most are translated into English, or translations are in progress.

- Heimskringla at World Wide School

- "icelandic sagas" at Northvegr

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle an XML edition by Tony Jebson (translation at The Medieval and Classical Literature Library)

- "Malcolm II, King of Alba 1005–1034". Scotland's History. BBC.