Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] (c. 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

| Edward the Confessor | |

|---|---|

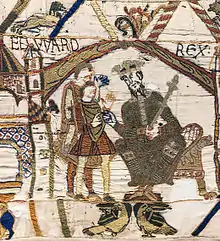

EDWARD(US) REX: Edward the Confessor, enthroned, opening scene of the Bayeux Tapestry | |

| King of the English | |

| Reign | 8 June 1042 – 5 January 1066 |

| Coronation | 3 April 1043, Winchester Cathedral |

| Predecessor | Harthacnut |

| Successor | Harold II |

| Born | c. 1003–1005 Islip, Oxfordshire, England |

| Died | 5 January 1066 (aged 60–63) London, England |

| Burial | Westminster Abbey, London |

| Spouse | Edith of Wessex |

| House | Wessex |

| Father | Æthelred the Unready |

| Mother | Emma of Normandy |

Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy. He succeeded Cnut the Great's son – and his own half-brother – Harthacnut. He restored the rule of the House of Wessex after the period of Danish rule since Cnut conquered England in 1016. When Edward died in 1066, he was succeeded by his wife's brother Harold Godwinson, who was defeated and killed in the same year by the Normans under William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings. Edward's young great-nephew Edgar the Ætheling of the House of Wessex was proclaimed king after the Battle of Hastings in 1066 but was never crowned and was peacefully deposed after about eight weeks.

Historians disagree about Edward's fairly long 24-year reign. His nickname reflects the traditional image of him as unworldly and pious. Confessor reflects his reputation as a saint who did not suffer martyrdom as opposed to his uncle, King Edward the Martyr. Some portray Edward the Confessor's reign as leading to the disintegration of royal power in England and the advance in power of the House of Godwin, because of the infighting that began after his death with no heirs to the throne. Biographers Frank Barlow and Peter Rex, on the other hand, portray Edward as a successful king, one who was energetic, resourceful and sometimes ruthless; they argue that the Norman conquest shortly after his death tarnished his image.[1][2] However, Richard Mortimer argues that the return of the Godwins from exile in 1052 "meant the effective end of his exercise of power", citing Edward's reduced activity as implying "a withdrawal from affairs".[3]

About a century later, in 1161, Pope Alexander III canonised the king. Edward was one of England's national saints until King Edward III adopted Saint George (George of Lydda) as the national patron saint in about 1350. Saint Edward's feast day is 13 October, celebrated by both the Church of England and the Catholic Church.

Early years and exile

Edward was the seventh son of Æthelred the Unready, and the first by his second wife, Emma of Normandy. Edward was born between 1003 and 1005 in Islip, Oxfordshire,[1] and is first recorded as a 'witness' to two charters in 1005. He had one full brother, Alfred, and a sister, Godgifu. In charters he was always listed behind his older half-brothers, showing that he ranked beneath them.[4]

During his childhood, England was the target of Viking raids and invasions under Sweyn Forkbeard and his son, Cnut. Following Sweyn's seizure of the throne in 1013, Emma fled to Normandy, followed by Edward and Alfred, and then by Æthelred. Sweyn died in February 1014, and leading Englishmen invited Æthelred back on condition that he promised to rule 'more justly' than before. Æthelred agreed, sending Edward back with his ambassadors.[5] Æthelred died in April 1016, and he was succeeded by Edward's older half-brother Edmund Ironside, who carried on the fight against Sweyn's son, Cnut. According to Scandinavian tradition, Edward fought alongside Edmund; as Edward was at most thirteen years old at the time, the story is disputed.[6][7] Edmund died in November 1016, and Cnut became undisputed king. Edward then again went into exile with his brother and sister; in 1017 his mother married Cnut.[1] In the same year, Cnut had Edward's last surviving elder half-brother, Eadwig, executed.[8]

Edward spent a quarter of a century in exile, probably mainly in Normandy, although there is no evidence of his location until the early 1030s. He probably received support from his sister Godgifu, who married Drogo of Mantes, count of Vexin in about 1024. In the early 1030s, Edward witnessed four charters in Normandy, signing two of them as king of England. According to William of Jumièges, the Norman chronicler, Robert I, Duke of Normandy attempted an invasion of England to place Edward on the throne in about 1034 but it was blown off course to Jersey. He also received support for his claim to the throne from several continental abbots, particularly Robert, abbot of the Norman abbey of Jumièges, who later became Edward's Archbishop of Canterbury.[9] Edward was said to have developed an intense personal piety during this period, but modern historians regard this as a product of the later medieval campaign for his canonisation. In Frank Barlow's view "in his lifestyle would seem to have been that of a typical member of the rustic nobility".[1][10] He appeared to have a slim prospect of acceding to the English throne during this period, and his ambitious mother was more interested in supporting Harthacnut, her son by Cnut.[1][11]

Cnut died in 1035, and Harthacnut succeeded him as king of Denmark. It is unclear whether he intended to keep England as well, but he was too busy defending his position in Denmark to come to England to assert his claim to the throne. It was therefore decided that his elder half-brother Harold Harefoot should act as regent, while Emma held Wessex on Harthacnut's behalf.[12] In 1036, Edward and his brother Alfred separately came to England. Emma later claimed that they came in response to a letter forged by Harold inviting them to visit her, but historians believe that she probably did invite them in an effort to counter Harold's growing popularity.[1][13] Alfred was captured by Godwin, Earl of Wessex who turned him over to Harold Harefoot. He had Alfred blinded by forcing red-hot pokers into his eyes to make him unsuitable for kingship, and Alfred died soon after as a result of his wounds. The murder is thought to be the source of much of Edward's hatred for Godwin and one of the primary reasons for Godwin's banishment in autumn 1051.[10] Edward is said to have fought a successful skirmish near Southampton, and then retreated back to Normandy.[14][lower-alpha 3] He thus showed his prudence, but he had some reputation as a soldier in Normandy and Scandinavia.[16]

In 1037, Harold was accepted as king, and the following year he expelled Emma, who retreated to Bruges. She then summoned Edward and demanded his help for Harthacnut, but he refused as he had no resources to launch an invasion, and disclaimed any interest for himself in the throne.[1][16] Harthacnut, his position in Denmark now secure, planned an invasion, but Harold died in 1040, and Harthacnut was able to cross unopposed, with his mother, to take the English throne.[17]

In 1041, Harthacnut invited Edward back to England, probably as heir because he knew he had not long to live.[12] The 12th-century Quadripartitus, in an account regarded as convincing by historian John Maddicott, states that he was recalled by the intervention of Bishop Ælfwine of Winchester and Earl Godwin. Edward met "the thegns of all England" at Hursteshever, probably modern Hurst Spit opposite the Isle of Wight. There he was received as king in return for his oath that he would continue the laws of Cnut.[18] According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Edward was sworn in as king alongside Harthacnut, but a diploma issued by Harthacnut in 1042 describes him as the king's brother.[19][20]

Early reign

Following Harthacnut's death on 8 June 1042, Godwin, the most powerful of the English earls, supported Edward, who succeeded to the throne.[1] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes the popularity he enjoyed at his accession – "before he [Harthacnut] was buried, all the people chose Edward as king in London."[21] Edward was crowned at the cathedral of Winchester, the royal seat of the West Saxons, on 3 April 1043.[22]

Edward complained that his mother had "done less for him than he wanted before he became king, and also afterwards". In November 1043, he rode to Winchester with his three leading earls, Leofric of Mercia, Godwin and Siward of Northumbria, to deprive her of her property, possibly because she was holding on to treasure which belonged to the king. Her adviser, Stigand, was deprived of his bishopric of Elmham in East Anglia. However, both were soon restored to favour. Emma died in 1052.[23] Edward's position when he came to the throne was weak. Effective rule required keeping on terms with the three leading earls, but loyalty to the ancient house of Wessex had been eroded by the period of Danish rule, and only Leofric was descended from a family which had served Æthelred. Siward was probably Danish, and although Godwin was English, he was one of Cnut's new men, married to Cnut's former sister-in-law. However, in his early years, Edward restored the traditional strong monarchy, showing himself, in Frank Barlow's view, "a vigorous and ambitious man, a true son of the impetuous Æthelred and the formidable Emma."[1]

In 1043, Godwin's eldest son Sweyn was appointed to an earldom in the south-west midlands, and on 23 January 1045 Edward married Godwin's daughter Edith. Soon afterwards, her brother Harold and her Danish cousin Beorn Estrithson were also given earldoms in southern England. Godwin and his family now ruled subordinately all of Southern England. However, in 1047 Sweyn was banished for abducting the abbess of Leominster. In 1049, he returned to try to regain his earldom, but this was said to have been opposed by Harold and Beorn, probably because they had been given Sweyn's land in his absence. Sweyn murdered his cousin Beorn and went again into exile, and Edward's nephew Ralph was given Beorn's earldom, but the following year Sweyn's father was able to secure his reinstatement.[24]

The wealth of Edward's lands exceeded that of the greatest earls, but they were scattered among the southern earldoms. He had no personal power base, and it seems he did not attempt to build one. In 1050–51 he even paid off the fourteen foreign ships which constituted his standing navy and abolished the tax raised to pay for it.[1][25] However, in ecclesiastical and foreign affairs he was able to follow his own policy. King Magnus I of Norway aspired to the English throne, and in 1045 and 1046, fearing an invasion, Edward took command of the fleet at Sandwich. Beorn's elder brother, Sweyn II of Denmark "submitted himself to Edward as a son", hoping for his help in his battle with Magnus for control of Denmark, but in 1047 Edward rejected Godwin's demand that he send aid to Sweyn, and it was only Magnus's death in October that saved England from attack and allowed Sweyn to take the Danish throne.[1]

Modern historians reject the traditional view that Edward mainly employed Norman favourites, but he did have foreigners in his household, including a few Normans, who became unpopular. Chief among them was Robert, abbot of the Norman abbey of Jumièges, who had known Edward from the 1030s and came to England with him in 1041, becoming bishop of London in 1043. According to the Vita Edwardi, he became "always the most powerful confidential adviser to the king".[26][27][lower-alpha 4]

Crisis of 1051–52

In ecclesiastical appointments, Edward and his advisers showed a bias against candidates with local connections, and when the clergy and monks of Canterbury elected a relative of Godwin as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1051, Edward rejected him and appointed Robert of Jumièges, who claimed that Godwin was in illegal possession of some archiepiscopal estates. In September 1051, Edward was visited by his brother-in-law, Godgifu's second husband, Eustace II of Boulogne. His men caused an affray in Dover, and Edward ordered Godwin as earl of Kent to punish the town's burgesses, but he took their side and refused. Edward seized the chance to bring his over-mighty earl to heel. Archbishop Robert accused Godwin of plotting to kill the king, just as he had killed his brother Alfred in 1036, while Leofric and Siward supported the king and called up their vassals. Sweyn and Harold called up their own vassals, but neither side wanted a fight, and Godwin and Sweyn appear to have each given a son as hostage, who were sent to Normandy. The Godwins' position disintegrated as their men were not willing to fight the king. When Stigand, who was acting as an intermediary, conveyed the king's jest that Godwin could have his peace if he could restore Alfred and his companions alive and well, Godwin and his sons fled, going to Flanders and Ireland.[1] Edward repudiated Edith and sent her to a nunnery, perhaps because she was childless,[29] and Archbishop Robert urged her divorce.[1]

Sweyn went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem (dying on his way back), but Godwin and his other sons returned, with an army following a year later, and received considerable support, while Leofric and Siward failed to support the king. Both sides were concerned that a civil war would leave the country open to foreign invasion. The king was furious, but he was forced to give way and restore Godwin and Harold to their earldoms, while Robert of Jumièges and other Frenchmen fled, fearing Godwin's vengeance. Edith was restored as queen, and Stigand, who had again acted as an intermediary between the two sides in the crisis, was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in Robert's place. Stigand retained his existing bishopric of Winchester, and his pluralism was a continuing source of dispute with the pope.[1][30] [lower-alpha 5]

Later reign

Until the mid-1050s Edward was able to structure his earldoms so as to prevent the Godwins from becoming dominant. Godwin died in 1053, and although Harold succeeded to his earldom of Wessex, none of his other brothers were earls at this date. His house was then weaker than it had been since Edward's succession, but a succession of deaths from 1055 to 1057 completely changed the control of earldoms. In 1055, Siward died, but his son was considered too young to command Northumbria, and Harold's brother, Tostig, was appointed. In 1057, Leofric and Ralph died, and Leofric's son Ælfgar succeeded as Earl of Mercia, while Harold's brother Gyrth succeeded Ælfgar as Earl of East Anglia. The fourth surviving Godwin brother, Leofwine, was given an earldom in the south-east carved out of Harold's territory, and Harold received Ralph's territory in compensation. Thus by 1057, the Godwin brothers controlled all of England subordinately apart from Mercia. It is not known whether Edward approved of this transformation or whether he had to accept it, but from this time he seems to have begun to withdraw from active politics, devoting himself to hunting, which he pursued each day after attending church.[1][32]

In the 1050s, Edward pursued an aggressive and generally successful policy in dealing with Scotland and Wales. Malcolm Canmore was an exile at Edward's court after his father, Duncan I, was killed in battle in 1040, against men led by Macbeth who seized the Scottish throne. In 1054, Edward sent Siward to invade Scotland. He defeated Macbeth, and Malcolm, who had accompanied the expedition, gained control of southern Scotland. By 1058, Malcolm had killed Macbeth in battle and had taken the Scottish throne. In 1059, he visited Edward, but in 1061, he started raiding Northumbria with the aim of adding it to his territory.[1][33]

In 1053, Edward ordered the assassination of the south Welsh prince Rhys ap Rhydderch in reprisal for a raid on England, and Rhys's head was delivered to him.[1] In 1055, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn established himself as the ruler of Wales, and allied himself with Ælfgar of Mercia, who had been outlawed for treason. They defeated Earl Ralph at Hereford, and Harold had to collect forces from nearly all of England to drive the invaders back into Wales. Peace was concluded with the reinstatement of Ælfgar, who was able to succeed as Earl of Mercia on his father's death in 1057. Gruffydd swore an oath to be a faithful under-king of Edward. Ælfgar likely died in 1062, and his young son Edwin was allowed to succeed as Earl of Mercia, but Harold then launched a surprise attack on Gruffydd. He escaped, but when Harold and Tostig attacked again the following year, he retreated and was killed by Welsh enemies. Edward and Harold were then able to impose vassalage on some Welsh princes.[34][35]

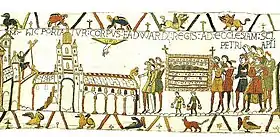

In October 1065, Harold's brother, Tostig, Earl of Northumbria, was hunting with the king when his thegns in Northumbria rebelled against his rule, which they claimed was oppressive, and killed some 200 of his followers. They nominated Morcar, the brother of Edwin of Mercia, as earl and invited the brothers to join them in marching south. They met Harold at Northampton, and Tostig accused Harold before the king of conspiring with the rebels. Tostig seems to have been a favourite with the king and queen, who demanded that the revolt be suppressed, but neither Harold nor anyone else would fight to support Tostig. Edward was forced to submit to his banishment, and the humiliation may have caused a series of strokes which led to his death.[1][36] He was too weak to attend the consecration of his new church at Westminster, which had been substantially completed in 1065, on 28 December.[37][38]

Edward probably entrusted the kingdom to Harold and Edith shortly before he died on 5 January 1066. On 6 January he was buried in Westminster Abbey, and Harold was crowned on the same day.[1]

Succession

Starting as early as William of Malmesbury in the early 12th century, historians have puzzled over Edward's intentions for the succession. One school of thought supports the Norman case that Edward always intended William the Conqueror to be his heir, accepting the medieval claim that Edward had already decided to be celibate before he married, but most historians believe that he hoped to have an heir by Edith at least until his quarrel with Godwin in 1051. William may have visited Edward during Godwin's exile, and he is thought to have promised William the succession at this time, but historians disagree on how seriously he meant the promise, and whether he later changed his mind.[lower-alpha 6]

Edmund Ironside's son, Edward the Exile, had the best claim to be considered Edward's heir. He had been taken as a young child to Hungary, and in 1054 Bishop Ealdred of Worcester visited the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry III to secure his return, probably with a view to becoming Edward's heir. The exile returned to England in 1057 with his family but died almost immediately.[39] His son Edgar, who was then about 6 years old, was brought up at the English court. He was given the designation Ætheling, meaning throneworthy, which may mean that Edward considered making him his heir, and he was briefly declared king after Harold's death in 1066.[40] However, Edgar was absent from witness lists of Edward's diplomas, and there is no evidence in the Domesday Book that he was a substantial landowner, which suggests that he was marginalised at the end of Edward's reign.[41]

After the mid-1050s, Edward seems to have withdrawn from affairs as he became increasingly dependent on the Godwins, and he may have become reconciled to the idea that one of them would succeed him. The Normans claimed that Edward sent Harold to Normandy in about 1064 to confirm the promise of the succession to William. The strongest evidence comes from a Norman apologist, William of Poitiers. According to his account, shortly before the Battle of Hastings, Harold sent William an envoy who admitted that Edward had promised the throne to William but argued that this was over-ridden by his deathbed promise to Harold. In reply, William did not dispute the deathbed promise but argued that Edward's prior promise to him took precedence.[42] In Stephen Baxter's view, Edward's "handling of the succession issue was dangerously indecisive, and contributed to one of the greatest catastrophes to which the English have ever succumbed."[43]

Westminster Abbey

Edward's Norman sympathies are most clearly seen in the major building project of his reign, Westminster Abbey, the first Norman Romanesque church in England. This was commenced between 1042 and 1052 as a royal burial church, consecrated on 28 December 1065, completed after his death in about 1090, and demolished in 1245 to make way for Henry III's new building, which still stands. It was very similar to Jumièges Abbey, which was built at the same time. Robert of Jumièges must have been closely involved in both buildings, although it is not clear which is the original and which the copy.[38] Edward does not appear to have been interested in books and associated arts, but his abbey played a vital role in the development of English Romanesque architecture, showing that he was an innovative and generous patron of the church.[44]

Veneration

Saint Edward | |

|---|---|

The left panel of the Wilton Diptych, where Edward (centre), with Edmund the Martyr (left) and John the Baptist, are depicted presenting Richard II to the Virgin Mary and Christ Child. | |

| Confessor of the Faith | |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Church of England Some Eastern Orthodox |

| Major shrine | Westminster Abbey, London |

| Feast | 13 October |

| Patronage | England, Monarchy of the United Kingdom, difficult marriages |

Edward the Confessor was the only king of England to be canonized by the pope, but he was part of a tradition of (uncanonised) Anglo-Saxon royal saints, such as Eadburh of Winchester, a daughter of Edward the Elder, Edith of Wilton, a daughter of Edgar the Peaceful, and the boy-king Edward the Martyr.[45] With his proneness to fits of rage and his love of hunting, Edward the Confessor is regarded by most historians as an unlikely saint, and his canonisation as political, although some argue that his cult started so early that it must have had something credible to build on.[46]

Edward displayed a worldly attitude in his church appointments. When he appointed Robert of Jumièges as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1051, he chose the leading craftsman Spearhafoc to replace Robert as Bishop of London. Robert refused to consecrate him, saying that the pope had forbidden it, but Spearhafoc occupied the bishopric for several months with Edward's support. After the Godwins fled the country, Edward expelled Spearhafoc, who fled with a large store of gold and gems which he had been given to make Edward a crown.[47] Stigand was the first archbishop of Canterbury not to be a monk in almost a hundred years, and he was said to have been excommunicated by several popes because he held Canterbury and Winchester in plurality. Several bishops sought consecration abroad because of the irregularity of Stigand's position.[48] Edward usually preferred clerks to monks for the most important and richest bishoprics, and he probably accepted gifts from candidates for bishoprics and abbacies. However, his appointments were generally respectable.[1] When Odda of Deerhurst died without heirs in 1056, Edward seized lands which Odda had granted to Pershore Abbey and gave them to his Westminster foundation; historian Ann Williams observes that "the Confessor did not in the 11th century have the saintly reputation which he later enjoyed, largely through the efforts of the Westminster monks themselves".[49]

After 1066, there was a subdued cult of Edward as a saint, possibly discouraged by the early Norman abbots of Westminster,[50] which gradually increased in the early 12th century.[51] Osbert of Clare, the prior of Westminster Abbey, then started to campaign for Edward's canonisation, aiming to increase the wealth and power of the Abbey. By 1138, he had converted the Vita Ædwardi Regis, the life of Edward commissioned by his widow, into a conventional saint's life.[50] He seized on an ambiguous passage which might have meant that their marriage was chaste, perhaps to give the idea that Edith's childlessness was not her fault, to claim that Edward had been celibate.[52] In 1139, Osbert went to Rome to petition for Edward's canonisation with the support of King Stephen, but he lacked the full support of the English hierarchy and Stephen had quarrelled with the church, so Pope Innocent II postponed a decision, declaring that Osbert lacked sufficient testimonials of Edward's holiness.[53]

In 1159, there was a disputed election to the papacy, and Henry II's support helped to secure the recognition of Pope Alexander III. In 1160, a new abbot of Westminster, Laurence, seized the opportunity to renew Edward's claim. This time, it had the full support of the king and the English hierarchy, and a grateful pope issued the bull of canonisation on 7 February 1161,[1] the result of a conjunction of the interests of Westminster Abbey, King Henry II and Pope Alexander III.[54] He was called 'Confessor' as the name for someone who was believed to have lived a saintly life but was not a martyr.[55] In the 1230s, King Henry III became attached to the cult of Saint Edward, and he commissioned a new life, by Matthew Paris.[56] Henry also constructed a grand new tomb for Edward in a rebuilt Westminster Abbey in 1269.[37] Henry III also named his eldest son after Edward.[57]

Until about 1350, Edmund the Martyr, Gregory the Great, and Edward the Confessor were regarded as English national saints, but Edward III preferred the more war-like figure of Saint George, and in 1348 he established the Order of the Garter with Saint George as its patron. At Windsor Castle, its chapel of Saint Edward the Confessor was re-dedicated to Saint George, who was acclaimed in 1351 as patron of the English race.[58] Edward was a less popular saint for many, but he was important to the Norman dynasty, which claimed to be the successor of Edward as the last legitimate Anglo-Saxon king.[59]

The shrine of Saint Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey remains where it was after the final translation of his body to a chapel east of the sanctuary on 13 October 1269 by Henry III.[60] The day of his translation, 13 October (his first translation had also been on that date in 1163), is an optional feast day in the Catholic Church of England and Wales,[61] and the Church of England's calendar of saints designates it as a Lesser Festival.[62][63] Each October the abbey holds a week of festivities and prayer in his honour.[64] Edward is also regarded as a patron saint of difficult marriages.[65] For some time the abbey had claimed that it possessed a set of coronation regalia that Edward had left for use in all future coronations. Following Edward's canonisation, these were regarded as holy relics, and thereafter they were used at all English coronations from the 13th century until the destruction of the regalia by Oliver Cromwell in 1649.[66] After the Stuart Restoration in 1660, the monarch had replicas of the destroyed regalia made for use in future coronations; these are still in use as part of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom for modern coronations of British monarchs, and one of the replicas, that of St Edward's Crown, is still a major symbol of the British monarchy.

Appearance and character

The Vita Ædwardi Regis states "[H]e was a very proper figure of a man – of outstanding height, and distinguished by his milky white hair and beard, full face and rosy cheeks, thin white hands, and long translucent fingers; in all the rest of his body he was an unblemished royal person. Pleasant, but always dignified, he walked with eyes downcast, most graciously affable to one and all. If some cause aroused his temper, he seemed as terrible as a lion, but he never revealed his anger by railing."[67] This, as the historian Richard Mortimer notes, 'contains obvious elements of the ideal king, expressed in flattering terms – tall and distinguished, affable, dignified and just.'[68]

Edward was allegedly not above accepting bribes. According to the Ramsey Liber Benefactorum, the monastery's abbot decided that it would be dangerous to publicly contest a claim brought by "a certain powerful man", but he claimed he was able to procure a favourable judgment by giving Edward twenty marks in gold and his wife five marks.[69]

See also

- Játvarðar Saga, Icelandic saga about the king

- St Edward's Crown

- St Edward's Sapphire

References

Notes

- The regnal numbering of English monarchs starts after the Norman conquest, which is why Edward the Confessor, who was the third King Edward, is not referred to as Edward III.

- (Old English: Ēadƿeard Andettere [ˈæːɑdwæɑrˠd ˈɑndettere]; Latin: Eduardus Confessor [ɛduˈardus kõːˈfɛssɔr], Ecclesiastical Latin: [eduˈardus konˈfessor];

- Pauline Stafford believes that Edward joined his mother at Winchester and returned to the continent after his brother's death.[15]

- Robert of Jumièges is usually described as Norman, but his origin is unknown, possibly Frankish.[28]

- Edward's nephew, Earl Ralph, who had been one of his chief supporters in the crisis of 1051–52, may have received Sweyn's marcher earldom of Hereford at this time.[31] However, Barlow 2006, states that Ralph received Hereford on Sweyn's first expulsion in 1047.

- Historians' views are discussed in Baxter 2009, pp. 77–118, which this section is based on.

Citations

- Barlow 2006.

- Rex 2008, p. 224.

- Mortimer 2009.

- Keynes 2009, p. 49.

- Rex 2008, pp. 13, 19.

- Barlow 1970, p. 29–36.

- Keynes 2009, p. 56.

- Panton 2011, p. 21.

- van Houts 2009, pp. 63–75.

- Howarth 1981.

- Rex 2008, p. 28.

- Lawson 2004.

- Rex 2008, pp. 34–35.

- Barlow 1970, pp. 44–45.

- Stafford 2001, pp. 239–240.

- Rex 2008, p. 33.

- Howard 2008, p. 117.

- Maddicott 2004, pp. 650–666.

- Mortimer 2009, p. 7.

- Baxter 2009, p. 101.

- Giles 1914, p. 114.

- Barlow 1970, p. 61.

- Rex 2008, pp. 48–49.

- Mortimer 2009, maps between pages 116 and 117.

- Mortimer 2009, pp. 26–28.

- van Houts 2009, p. 69.

- Gem 2009, p. 171.

- van Houts 2009, p. 70.

- Williams 2004a.

- Rex 2008, p. 107.

- Williams 2004b.

- Baxter 2009, pp. 103–104.

- Barrow 2008.

- Walker 2004.

- Williams 2004c.

- Aird 2004.

- "History of Westminster Abbey". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- Fernie 2009, pp. 139–143.

- Baxter 2009, pp. 96–98.

- Hooper 2004.

- Baxter 2009, pp. 98–103.

- Baxter 2009, pp. 103–114.

- Baxter 2009, p. 118.

- Mortimer 2009, p. 23.

- Bozoky 2009, pp. 178–179.

- Mortimer 2009, pp. 29–32.

- Blair 2004.

- Cowdrey 2004.

- Williams 1997, p. 11.

- Barlow 2004.

- Rex 2008, pp. 214–217.

- Baxter 2009, pp. 84–85.

- Bozoky 2009, pp. 180–181.

- Bozoky 2009, p. 173.

- Rex 2008, p. 226.

- Carpenter 2007, pp. 865–891.

- Jones 2014, pp. 241–242.

- Summerson 2004.

- Bozoky 2009, pp. 180–182.

- "Visiting the Abbey : Edward The Confessor". Westminster Abbey. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011.

- "Liturgical Calendar : October 2020". The Catholic Church in England and Wales. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- "Holy Days". Church of England. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016.

- "Edwardtide". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Saint Edward the Confessor". CatholicSaints.Info. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Keay 2002.

- Barlow 1992, p. 19.

- Mortimer 2009, p. 15.

- Molyneaux 2015, p. 218.

Sources

- Aird, William M. (23 September 2004). "Tostig". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27571. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Barlow, Frank (1970). Edward the Confessor. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01671-2.

- Barlow, Frank (1992). The Life of King Edward who Rests at Westminster. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820203-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=BLDoMHk4AZ8C.

- Barlow, Frank (23 September 2004). "Osbert of Clare". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5442. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Barlow, Frank (25 May 2006). "Edward (St Edward; known as Edward the Confessor)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8516. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Barrow, G. W. S. (3 January 2008). "Malcolm III". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17859. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Baxter, Stephen (2009). "Edward the Confessor and the Succession Question". In Mortimer, Richard (ed.). Edward the Confessor: the man and the legend. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-436-6. OL 23632597M.

- Blair, John (23 September 2004). "Spearhafoc". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49416. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Bozoky, Edina (2009). "The Sanctity and Canonisation of Edward the Confessor". In Mortimer, Richard (ed.). Edward the Confessor: the man and the legend. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-436-6. OL 23632597M.

- Carpenter, D. A. (1 September 2007). "King Henry III and Saint Edward the Confessor: The Origins of the Cult". The English Historical Review. CXXII (498): 865–891. doi:10.1093/ehr/cem214 – via academic.oup.com.

- Cowdrey, H. E. J. (23 September 2004). "Stigand". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26523. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Fernie, Eric (2009). "Edward the Confessor's Westminster Abbey". In Mortimer, Richard (ed.). Edward the Confessor: the man and the legend. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-436-6. OL 23632597M.

- Gem, Richard (2009). "Craftsmen and administrators in the building of the Confessor's Abbey". In Mortimer, Richard (ed.). Edward the Confessor: the man and the legend. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-436-6. OL 23632597M.

- Giles, J.A. (1914). . London: G. Bell and Sonson. p. – via Wikisource.

- Hooper, Nicholas (23 September 2004). "Edgar Ætheling". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8465. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Howard, Ian (2008). Harthacnut: The Last Danish King of England. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-4674-5.

- Howarth, David (1981). 1066: The Year of the Conquest. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-005850-8.

- Jones, Dan (2014). The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England. Penguin. ISBN 978-0143124924.

- Keay, A. (2002). The Crown Jewels. London: The Historic Royal Palaces. ISBN 1-873993-20-X.

- Keynes, Simon (2009). "Edward the Ætheling". In Mortimer, Richard (ed.). Edward the Confessor: the man and the legend. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-436-6. OL 23632597M.

- Lawson, M. K. (23 September 2004). "Harthcnut". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12252. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Maddicott, J. R. (2004). "Edward the Confessor's Return to England in 1041". English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. CXIX (482): 650–666. doi:10.1093/ehr/119.482.650.

- Molyneaux, George (2015). The Formation of the English Kingdom in the Tenth Century. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871791-1.

- Mortimer, Richard, ed. (2009). Edward the Confessor: the man and the legend. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-436-6. OL 23632597M.

- Panton, James (2011). Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7497-8.

- Rex, Peter (2008). King & Saint: The Life of Edward the Confessor. Stroud: History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-4602-8.

- Stafford, Pauline (2001). Queen Emma and Queen Edith: Queenship and Women's Power in Eleventh-Century England. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-22738-0.

- Summerson, Henry (23 September 2004). "Saint George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/60304. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- van Houts, Elisabeth (2009). "Edward and Normandy". In Mortimer, Richard (ed.). Edward the Confessor: the man and the legend. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-436-6. OL 23632597M.

- Walker, David (23 September 2004). "Gruffydd ap Llywelyn". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11695. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Williams, Ann (1997). Land, power and politics: the family and career of Odda of Deerhurst (Deerhurst Lecture 1996). Deerhurst: Friends of Deerhurst Church. ISBN 0-9521199-2-7.

- Williams, Ann (23 September 2004a). "Edith (d.1075)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8483. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Williams, Ann (23 September 2004b). "Ralph the Timid". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23045. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Williams, Ann (23 September 2004c). "Ælfgar". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/178. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, tr. Michael Swanton, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. 2nd ed. London, 2000.

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Life of St. Edward the Confessor, translated Fr. Jerome Bertram (first English translation) St. Austin Press ISBN 1-901157-75-X

- Keynes, Simon (1991). "The Æthelings in Normandy". Anglo-Norman Studies. The Boydell Press. XIII. ISBN 0-85115-286-4.

- Licence, Tom (2016). "Edward the Confessor and the Succession Question: A Fresh Look at the Sources". Anglo-Norman Studies. 39. ISBN 9781783272211.

- Licence, Tom (2020). Edward the Confessor: Last of the Royal Blood. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21154-2.

- O'Brien, Bruce R.: God's Peace and King's Peace: The Laws of Edward the Confessor, Philadelphia, Pa. : University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8122-3461-8

- The Waltham Chronicle ed. and trans. Leslie Watkiss and Marjorie Chibnall, Oxford Medieval Texts, OUP, 1994

- William of Malmesbury, The History of the English Kings, i, ed.and trans. R. A. B. Mynors, R. M. Thomson and M. Winterbottom, Oxford Medieval Texts, OUP 1998