Saint Joseph

Joseph (Hebrew: יוסף, romanized: Yosef; Greek: Ἰωσήφ, romanized: Ioséph) was a 1st-century Jewish man of Nazareth who, according to the canonical Gospels, was married to Mary, the mother of Jesus, and was the legal father of Jesus.[2] The Gospels also name some brothers of Jesus which may have been: (1) the sons of Mary, the mother of Jesus, and Joseph; (2) sons of Mary, the wife of Clopas and sister of Mary the mother of Jesus; or (3) sons of Joseph by a former marriage.[3]

Joseph | |

|---|---|

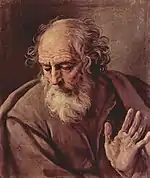

Saint Joseph with the Infant Jesus by Guido Reni, c. 1635 | |

| Spouse of the Blessed Virgin Mary Legal father of Jesus Prince and Patron of the Universal Church Guardian of the Holy Family | |

| Venerated in | All Christian denominations that venerate saints |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Carpenter's square or tools, holding the infant Jesus Christ, staff with lily blossoms, two turtle doves, and the rod of spikenard. |

| Patronage | Catholic Church, among others fathers, workers, married people, persons living in exile, the sick and dying, for a holy death |

| Part of a series on |

| Josephology of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| General articles |

|

| Prayers and devotions |

|

| Organisations |

|

| Papal documents |

|

|

|

Joseph is venerated as Saint Joseph in the Catholic Church, Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Church and Anglicanism. His feast day is observed by some Lutherans.[4][5] In Catholic traditions, Joseph is regarded as the patron saint of workers and is associated with various feast days. The month of March is dedicated to Saint Joseph. Pope Pius IX declared him to be both the patron and the protector of the Catholic Church, in addition to his patronages of the sick and of a happy death, due to the belief that he died in the presence of Jesus and Mary. Joseph has become patron of various dioceses and places. Being a patron saint of the virgins, too, he is venerated as "most chaste".[6][7] A specific veneration is tributed to the most chaste and pure heart of Saint Joseph.[8]

Several venerated images of Saint Joseph have been granted a decree of canonical coronation by a pontiff. Religious iconography often depicts him with lilies or spikenard. With the present-day growth of Mariology, the theological field of Josephology has also grown and since the 1950s centers for studying it have been formed.[9][10]

In the New Testament

The Pauline epistles are the oldest extant Christian writings.[11] These mention Jesus' mother (without naming her), but do not refer to his father. The Gospel of Mark, believed to be the first gospel to be written and with a date about two decades after Paul, also does not mention Jesus' father.[12]

The first appearance of Joseph is in the gospels of Matthew and Luke, often dated from around 80–90 AD. Each contains a genealogy of Jesus showing ancestry from King David, but through different sons; Matthew follows the major royal line from Solomon, while Luke traces another line back to Nathan, another son of David and Bathsheba. Consequently, all the names between David and Joseph are different.

Like the two differing genealogies, the infancy narratives appear only in Matthew and Luke and take different approaches to reconciling the requirement that the Messiah be born in Bethlehem with the tradition that Jesus in fact came from Nazareth. In Matthew, Joseph obeys the direction of an angel to marry Mary. Following the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem, Joseph is told by an angel in a dream to take the family to Egypt to escape the massacre of the children of Bethlehem planned by Herod, the ruler of the Roman province of Judea. Once Herod has died, an angel tells Joseph to return but to avoid Herod's son, and he takes his wife and the child to Nazareth in Galilee and settles there. Thus in Matthew, the infant Jesus, like Moses, is in peril from a cruel king, like Moses he has a (fore)father named Joseph who goes down to Egypt, like the Old Testament Joseph this Joseph has a father named Jacob, and both Josephs receive important dreams foretelling their future.[13]

In the Gospel book of Luke, Joseph already lives in Nazareth, and Jesus is born in Bethlehem because Joseph and Mary have to travel there to be counted in a census. Subsequently, Jesus was born there. Luke's account makes no mention of him being visited by angels (Mary and various others instead receive similar visitations), the Massacre of the Innocents, or of a visit to Egypt.

The last time Joseph appears in person in any of the canonical Gospels is in the narrative of the Passover visit to the Temple in Jerusalem when Jesus is 12 years old, which is found only in Luke. No mention is made of him thereafter.[14] The story emphasizes Jesus' awareness of his coming mission: here Jesus speaks to his parents (both of them) of "my father," meaning God, but they fail to understand (Luke 2:41–51).

Christian tradition represents Mary as a widow during the adult ministry of her son. Joseph is not mentioned as being present at the Wedding at Cana at the beginning of Jesus' mission, nor at the Passion at the end. If he had been present at the Crucifixion, he would under Jewish custom have been expected to take charge of Jesus' body, but this role is instead performed by Joseph of Arimathea. Nor would Jesus have entrusted his mother to the care of John the Apostle if her husband had been alive.[15]

While none of the Gospels mentions Joseph as present at any event during Jesus' adult ministry, the synoptic Gospels share a scene in which the people of Nazareth, Jesus' hometown, doubt Jesus' status as a prophet because they know his family. In Mark 6:3, they call Jesus "Mary's son" instead of naming his father. In Matthew, the townspeople call Jesus "the carpenter's son," again without naming his father. (Matthew 13:53–55) In Luke 3:23 NIV: "Now Jesus himself was about thirty years old when he began his ministry. He was the son, so it was thought, of Joseph, the son of Heli," (Luke 3:21–38); or alternatively punctuated: "(ὡς ἐνομ. τοῦ Ἰωσὴφ) τοῦ Ἡλί, ‘the son (as supposed of Joseph, but in reality) of Heli'".[16] In Luke the tone of the contemporary people is positive, whereas in Mark and Matthew it is disparaging.[17] This incident does not appear in John, but in a parallel story the disbelieving neighbors refer to "Jesus the son of Joseph, whose father and mother we know" (John 6:41–51).

Mentions in the Gospels

| No. | Event | Matthew | Mark | Luke | John |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Joseph lived in Nazareth | Luke 2:4 | |||

| 2 | Genealogy of Jesus | Matthew 1:1–17 Solomon to Jacob | Luke 3:23 Nathan to Heli | ||

| 3 | Joseph Betrothed to Mary | Matthew 1:18 | |||

| 4 | Angel visits Joseph (1st dream) | Matthew 1:20–21 | |||

| 5 | Joseph and Mary travel to Bethlehem | Luke 2:1–5 | |||

| 6 | Birth of Jesus | Matthew 1:25 | Luke 2:6–7 | ||

| 7 | Temple presentation | Luke 2:22–24 | |||

| 8 | Angel tells Joseph to flee (2nd dream) | Matthew 2:13 | |||

| 9 | Flight into Egypt | Matthew 2:14–15 | |||

| 10 | Angel tells Joseph to return to Nazareth (3rd dream) | Matthew 2:19–20 | |||

| 11 | Joseph and family settle in Nazareth | Matthew 2:21–23 | Luke 2:39 | ||

| 12 | Finding Jesus in the Temple | Luke 2:41–51 | |||

| 13 | Holy Family | John 6:41–42 | |||

Lineage

Joseph appears in Luke as the father of Jesus and in a "variant reading in Matthew".[18] Matthew and Luke both contain a genealogy of Jesus showing his ancestry from David, but through different sons; Matthew follows the major royal line from Solomon, while Luke traces another line back to Nathan, another son of David and Bathsheba. Consequently, all the names between David and Joseph are different. According to Matthew 1:16 "Jacob begat Joseph the husband of Mary", while according to Luke 3:23, Joseph is said to be "the son of Heli".

The variances between the genealogies given in Matthew and Luke are explained in a number of ways. One possibility is that Matthew's genealogy traces Jesus' legal descent, according to Jewish law, through Joseph; while Luke's genealogy traces his actual physical descent through Mary.[19][20] Another possibility proposed by Julius Africanus is that both Joseph and his father were the sons of Levirate marriages.[21][22] A third explanation proposed by Augustine of Hippo is that Joseph was adopted, and his two genealogies trace Joseph's lineage through his biological and adopted families.[23]

Professional life

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

In the Gospels, Joseph's occupation is mentioned only once. The Gospel of Matthew[13:55] asks about Jesus:

Is not this the carpenter's son (ho tou tektōnos huios)?

Joseph's description as a "tekton" (τέκτων) has been traditionally translated into English as "carpenter", but is a rather general word (from the same root that gives us "technical" and "technology"[24]) that could cover makers of objects in various materials.[25] The Greek term evokes an artisan with wood in general, or an artisan in iron or stone.[26] But the specific association with woodworking is a constant in Early Christian tradition; Justin Martyr (died c. 165) wrote that Jesus made yokes and ploughs, and there are similar early references.[27]

Other scholars have argued that tekton could equally mean a highly skilled craftsman in wood or the more prestigious metal, perhaps running a workshop with several employees, and noted sources recording the shortage of skilled artisans at the time.[28] Geza Vermès has stated that the terms 'carpenter' and 'son of a carpenter' are used in the Jewish Talmud to signify a very learned man, and he suggests that a description of Joseph as 'naggar' (a carpenter) could indicate that he was considered wise and highly literate in the Torah.[29] At the time of Joseph, Nazareth was an obscure village in Galilee, about 65 kilometres (40 mi) from the Holy City of Jerusalem, and is barely mentioned in surviving non-Christian texts and documents.[30][31][32][33] Archaeology over most of the site is made impossible by subsequent building, but from what has been excavated and tombs in the area around the village, it is estimated that the population was at most about 400.[34] It was, however, only about 6 kilometers from the city of Sepphoris, which was destroyed and depopulated by the Romans in 4 BC, and thereafter was expensively rebuilt. Analysis of the landscape and other evidence suggest that in Joseph's lifetime Nazareth was "oriented toward" the nearby city,[35] which had an overwhelmingly Jewish population although with many signs of Hellenization,[36] and historians have speculated that Joseph and later Jesus too might have traveled daily to work on the rebuilding. Specifically the large theatre in the city has been suggested, although this has aroused much controversy over dating and other issues.[37] Other scholars see Joseph and Jesus as the general village craftsmen, working in wood, stone, and metal on a wide variety of jobs.[38]

Modern appraisal

The name "Joseph" is found almost exclusively in the genealogies and the infancy narratives.[39][40] Modern positions on the question of the relationship between Joseph and the Virgin Mary vary. The Eastern Orthodox Church, which names Joseph's first wife as Salome, holds that Joseph was a widower and betrothed to Mary,[41] and that references to Jesus' "brothers" were children of Joseph from a previous marriage. The position of the Catholic Church, derived from the writings of Jerome, is that Joseph was the husband of Mary, but that references to Jesus' "brothers" should be understood to mean cousins. Such usage is prevalent throughout history, and occurs elsewhere in the Bible. Abraham's nephew Lot (Genesis 11:26-28) was referred to as his brother (Genesis 14:14), as was Jacob's uncle Laban (Genesis 29:15). Jesus himself frequently used the word "brother" as a generic term for one's fellow man. This custom has continued into modern times, with close friends, colleagues, and fellow churchgoers often called "brothers and sisters." Generally, most Protestants read "brothers and sisters" of Jesus as referring specifically to children born of Mary. The doctrine of the Perpetual virginity of Mary means among other things that Joseph and Mary never had sexual relations.

The term kiddushin, which refers to the first part of a two-part marriage, is frequently translated as "betrothal". Couples who fulfill the requirements of the kiddushin are married, until death or divorce.[42][43][44]

Death

The New Testament has no mention of Joseph's death, but he is never mentioned after Jesus's childhood, and Mary is always presented as by herself, often dressed as a widow, in other texts and art covering the period of the ministry and passion of Jesus. By contrast, the apocryphal History of Joseph the Carpenter, from the 5th or 6th century, has a long account of Joseph's peaceful death, at the age of 111, in the presence of Jesus (aged about 19), Mary and angels. This scene starts to appear in art in the 17th century.[45]

Later apocryphal writings

.jpg.webp)

The canonical gospels created a problem: they stated clearly that Mary was a virgin when she conceived Jesus, and that Joseph was not his father; however, Jesus was described unambiguously by John and Matthew as "Joseph's son" and "the carpenter's son", yet Joseph's paternity was essential to establish Jesus' Davidic descent. The theological situation was complicated by the gospel references to "brothers and sisters" of Jesus.[46] From the 2nd century to the 5th writers tried to explain how Jesus could be simultaneously the "son of God" and the "son of Joseph".[46]

The first to offer a solution was the apocryphal Gospel of James (also known as the Protoevangelium of James), written about 150 AD. The original gospels never refer to Joseph's age, but the author presents him as an old man chosen by lot (i.e., by God) to watch over the Virgin. Jesus' brothers are presented as Joseph's children by an earlier marriage."[47]

The apocryphal History of Joseph the Carpenter, written in the 5th century and framed as a biography of Joseph dictated by Jesus, describes how Joseph, aged 90, a widower with four sons and two daughters, is given charge of the twelve-year-old Mary, who then lives in his household raising his youngest son James the Less (the supposed author of the Protoevangelium) until she is ready to be married at age 14½. Joseph's death at the age of 111, attended by angels and asserting the perpetual virginity of Mary, takes up approximately half the story.[48]

Church Fathers

According to the bishop of Salamis, Epiphanius, in his work The Panarion (AD 374–375) Joseph became the father of James and his three brothers (Joses, Simeon, Judah) and two sisters (a Salome and a Mary[49] or a Salome and an Anna[50]) with James being the eldest sibling. James and his siblings were not children of Mary but were Joseph's children from a previous marriage. After Joseph's first wife died, many years later when he was eighty, "he took Mary (mother of Jesus)".[51][52]

Eusebius of Caesarea relates in his Church History (Book III, ch. 11) that "Hegesippus records that Clopas was a brother of Joseph and an uncle of Jesus."[53] Epiphanius adds that Joseph and Cleopas were brothers, sons of "Jacob, surnamed Panther."[54]

Origen quotes the Greek philosopher and opponent of early Christianity Celsus (from his work On the True Doctrine, c. 178 AD) as controversially asserting that Joseph left Mary upon learning of her pregnancy: "...when she was pregnant she was turned out of doors by the carpenter to whom she had been betrothed, as having been guilty of adultery, and that she bore a child to a certain soldier named Panthera."[55] Origen, however, argues that Celsus's claim was a fabricated story.[56]

Veneration

The earliest records of a formal devotional following for Saint Joseph date to the year 800 and references to him as Nutritor Domini (educator/guardian of the Lord) began to appear in the 9th century, and continued growing to the 14th century.[57][58][59] Thomas Aquinas discussed the necessity of the presence of Saint Joseph in the plan of the Incarnation for if Mary had not been married, the Jews would have stoned her and that in his youth Jesus needed the care and protection of a human father.[60][61]

In the 15th century, major steps were taken by Bernardine of Siena, Pierre d'Ailly, and Jean Gerson.[57] Gerson wrote Consideration sur Saint Joseph and preached sermons on Saint Joseph at the Council of Constance.[62] In 1889 Pope Leo XIII issued the encyclical Quamquam pluries in which he urged Catholics to pray to Saint Joseph, as the patron of the church in view of the challenges facing the church. Likewise, Leo stated that Saint Joseph "set himself to protect with a mighty love and a daily solicitude his spouse and the Divine Infant; regularly by his work he earned what was necessary for the one and the other for nourishment and clothing"[63]

Josephology, the theological study of Saint Joseph, is one of the most recent theological disciplines.[64] In 1989, on the occasion of the centenary of Quamquam pluries Pope John Paul II issued Redemptoris Custos (Guardian of the Redeemer), which presented Saint Joseph's role in the plan of redemption, as part of the "redemption documents" issued by John Paul II such as Redemptoris Mater to which it refers.[65][66][67][68]

Together with the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Child Jesus, Joseph is one of the three members of the Holy Family; since he only appears in the birth narratives of the Gospels, Jesus is depicted as a child when with him. The formal veneration of the Holy Family began in the 17th century by François de Laval.

In 1962, Pope John XXIII inserted the name of Joseph in the Canon of the Mass, immediately after that of the Blessed Virgin Mary. In 2013, Pope Francis had his name added to the three other Eucharistic Prayers.[69]

Feast days

| Feast of Saint Joseph | |

|---|---|

Saint Joseph and the Christ Child by Guido Reni, 1640 | |

| Observed by | Catholic Church Lutheran Church |

| Celebrations | Carrying blessed fava beans, wearing red-coloured clothing, assembling home altars dedicated to Saint Joseph, attending a Saint Joseph's Day parade |

| Observances | Church attendance at Mass or Divine Service |

| Begins | 19 March |

| Frequency | annual |

Saint Joseph's Day

19 March, Saint Joseph's Day, has been the principal feast day of Saint Joseph in Western Christianity[70][71] since the 10th century, and is celebrated by Catholics, Anglicans, many Lutherans, and other denominations.[72] In Eastern Orthodoxy, the feast day of Saint Joseph is celebrated on the First Sunday after the Nativity of Christ. In the Catholic Church, the Feast of Saint Joseph (19 March) is a solemnity (first class if using the Tridentine calendar), and is transferred to another date if impeded (i.e., 19 March falling on Sunday or in Holy Week).

Joseph is remembered in the Church of England and the Episcopal Church on 19 March.[73][74]

Popular customs among Christians of various liturgical traditions observing Saint Joseph's Day are attending Mass or the Divine Service, wearing red-coloured clothing, carrying dried fava beans that have been blessed, and assembling home altars dedicated to Saint Joseph.[75]

In Sicily, where Saint Joseph is regarded by many as their patron saint, and in many Italian-American communities, thanks are given to Saint Joseph (San Giuseppe in Italian) for preventing a famine in Sicily during the Middle Ages. According to legend, there was a severe drought at the time, and the people prayed for their patron saint to bring them rain. They promised that if God answered their prayers through Joseph's intercession, they would prepare a large feast to honor him. The rain did come, and the people of Sicily prepared a large banquet for their patron saint. The fava bean was the crop which saved the population from starvation and is a traditional part of Saint Joseph's Day altars and traditions. Giving food to the needy is a Saint Joseph's Day custom. In some communities it is traditional to wear red clothing and eat a Neapolitan pastry known as a zeppola (created in 1840 by Don Pasquale Pinatauro in Naples) on Saint Joseph's Day.[76] Maccu di San Giuseppe is a traditional Sicilian dish that consists of various ingredients and maccu that is prepared on this day.[77] Maccu is a foodstuff and soup that dates to ancient times which is prepared with fava beans as a primary ingredient.[77]

Upon a typical Saint Joseph's Day altar, people place flowers, limes, candles, wine, fava beans, specially prepared cakes, breads, cookies, other meatless dishes, and zeppole. Foods are traditionally served containing bread crumbs to represent sawdust since Joseph was a carpenter. Because the feast occurs during Lent, traditionally no meat was allowed on the celebration table. The altar usually has three tiers, to represent the Trinity.[78]

Saint Joseph the Worker

In 1870, Pope Pius IX declared Joseph patron of the Universal Church and instituted another feast, a solemnity to be held on the third Sunday of Eastertide. Pope Pius X, in order to restore the celebration of Sundays, moved this feast to the Wednesday in the second week after Easter, and gave it an octave. In 1955, Pope Pius XII introduced in its place the feast of Saint Joseph the Worker on 1 May in the General Roman Calendar as an ecclesiasical counterpart to the International Workers' Day on the same day.[79][80] This reflects Saint Joseph's status as patron of workers. Pius XII established the feast both to honor Saint Joseph, and to make people aware of the dignity of human work.[81]

Espousals of the Blessed Virgin Mary

The Espousals of the Blessed Virgin Mary is observed in some liturgical calendars (e. g. that of the Oblates of Saint Joseph) on 23 January.

Patris corde and Year of Saint Joseph

Pope Francis on 8 December 2020, released the apostolic letter Patris corde on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the declaration by Pius IX, on 8 December 1870, of Saint Joseph as patron of the Universal Church; for the same reason he declared a Year of Saint Joseph, from 8 December 2020, to 8 December 2021.[82][83]

Patronage

Pope Pius IX proclaimed Saint Joseph the patron of the Universal Church in 1870. Having died in the "arms of Jesus and Mary" according to Catholic tradition, he is considered the model of the pious believer who receives grace at the moment of death, in other words, the patron of a happy death.[84]

Saint Joseph is well known as the patron saint of fathers, both families and virgins, workers, especially carpenters, expecting mothers and unborn children. Among many others, he is the patron saint of attorneys and barristers, emigrants, travelers and house hunters. He is invoked against hesitation and for the grace of a holy death.[85]

Places, churches, and institutions

Many cities, towns, and locations are named after Saint Joseph. According to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Spanish form, San Jose, is the most common place name in the world. Probably the most-recognized San Joses are San José, Costa Rica, and San Jose, California, United States, given their name by Spanish colonists. Joseph is the patron saint of the New World; and of the regions Carinthia, Styria, Tyrol, Sicily; and of several main cities and dioceses.

Many churches, monasteries and other institutions are dedicated to Saint Joseph. Saint Joseph's Oratory is the largest church in Canada, with the largest dome of its kind in the world after that of Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome. Elsewhere in the world churches named after the saint may be known as those of San Giuseppe, e.g. San Giuseppe dei Teatini, San José, e.g. Metropolitan Cathedral of San José or São José, e.g. in Porto Alegre, Brazil.

The Sisters of St. Joseph were founded as an order in 1650 and have about 14,013 members worldwide. In 1871, the Josephite Fathers of the Catholic Church were created under the patronage of Joseph, intending to work with the poor. The first Josephites in America re-devoted their part of the order to ministry within the newly emancipated African American community. The Oblates of St. Joseph were founded in 1878 by Joseph Marello. In 1999 their Shrine of Saint Joseph the Guardian of the Redeemer was named after the Apostolic exhortation Redemptoris Custos.[86]

Prayers and devotions

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, during the feast day of Saint Joseph the following hymn is chanted:

Verily, Joseph the betrothed, saw clearly in his old age that the foresayings of the Prophets had

been fulfilled openly; for he was given an odd earnest,

receiving inspiration from the angels,

who cried, Glory to God; for he hath bestowed peace on earth.

In the Catholic tradition, just as there are prayers for the Seven Joys of Mary and Seven Sorrows of Mary, there are also prayers for the seven joys and seven sorrows of Saint Joseph. Furthermore, there is a novena prayed before the feast of Saint Joseph on 19 March. Saint Joseph is frequently invoked for employment, daily protection, vocation, happy marriage, and a happy death.[87][88][89]

Multiple venerated Catholics have described their devotion to Saint Joseph and his intercession. Francis de Sales included Saint Joseph along with Virgin Mary as saints to be invoked during prayers in his 1609 book, Introduction to the Devout Life.[90] Teresa of Ávila attributed her recovery of health to Saint Joseph and recommended him as an advocate.[91] Therese of Lisieux stated that she prayed daily to "Saint Joseph, Father and Protector of Virgins" and felt protected from danger as a result.[92] Pope Pius X composed a prayer to Saint Joseph which begins:[93]

Glorious St. Joseph, pattern of all who are devoted to toil,

obtain for me the grace to toil, in the spirit of penance,

in order to thereby atone for my many sins …

There is a Catholic tradition that burying a statuette of Saint Joseph on the grounds of a home will help to sell or buy[94] a house.;[95] this tradition became so popular through the World Wide Web that some American realtors bought them by the gross.[96]

St. Joseph's role in the Catholic church is summarized by the German theologian Friedrich Justus Knecht:

St. Joseph’s high place in the kingdom of God comes from this, that God chose him to be the guardian and protector of His Son, entrusting him with what was greatest and dearest to Himself, singling him out and especially blessing him for this office. The Church celebrates a Feast in honour of St. Joseph on March 19th, and desires that all the faithful should honour him, ask for his intercession, and imitate his virtues. St. Joseph is the especial patron of the Church. Even as he was the protector of the Child Jesus on earth, so, we believe, is he now the protector of the mystical Body of Jesus, His holy Church. We also especially seek his intercession for a good death, because, having died so blessedly, in the presence and with the assistance of Jesus and Mary, he should be supplicated to obtain for us from Jesus the grace of a happy death.[97]

In art

In mosaics in the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore (432-40) Joseph is portrayed young, bearded and dressed as a Roman of status.[98] Joseph is shown mostly with a beard, not only in keeping with Jewish custom, but also because – although the Gospel accounts do not give his age – later legends tend to present him as an old man at the time of his wedding to Mary. Earlier writers thought the traditional imagery necessary to support belief in Mary's perpetual virginity.[99] Jean Gerson nonetheless favoured showing him as a younger man.[100]

In recent centuries – in step with a growing interest in Joseph's role in Gospel exegesis – he himself has become a focal figure in representations of the Holy Family. He is now often portrayed as a younger or even youthful man (perhaps especially in Protestant depictions), whether going about his work as a carpenter, or participating actively in the daily life of Mary and Jesus as an equal and openly affectionate member.[101] Art critic Waldemar Januszczak however emphasises the preponderance of Joseph's representation as an old man and sees this as the need:

to explain away his impotence: indeed to symbolise it. In Guido Reni's Nativity, Mary is about 15, and he is about 70 – for the real love affair – is the one between the Virgin Mary and us. She is young. She is perfect. She is virginal – it is Joseph's task to stand aside and let us desire her, religiously. It takes a particularly old, a particularly grey, a particularly kindly and a particularly feeble man to do that. ...Banished in vast numbers to the backgrounds of all those gloomy stables in all those ersatz Bethlehems, his complex iconographic task is to stand aside and let his wife be worshipped by the rest of us.[102]

However Carolyn Wilson challenges the long-held view that pre-Tridentine images were often intended to demean him.[103] According to Charlene Villaseñor Black, "Seventeenth-century Spanish and Mexican artists reconceptualized Joseph as an important figure, ... representing him as the youthful, physically robust, diligent head of the Holy Family."[104] In Bartolomé Esteban Murillo's The Two Trinities, Saint Joseph is given the same prominence as the Virgin.

Full cycles of his life are rare in the Middle Ages, although the scenes from the Life of the Virgin or Life of Christ where he is present are far more often seen. The Mérode Altarpiece of about 1425, where he has a panel to himself, working as a carpenter, is an early example of what remained relatively rare depictions of him pursuing his métier.

Some statues of Joseph depict his staff as topped with flowers, recalling the non-canonical Gospel of James's account of how Mary's spouse was chosen by collecting the walking sticks of widowers in Palestine, and Joseph's alone bursting into flower, thus identifying him as divinely chosen. The Golden Legend, which derives its account from the much older Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, tells a similar story, although it notes that all marriageable men of the Davidic line and not only widowers were ordered by the High Priest to present their rods at the Temple. Several Eastern Orthodox Nativity icons show Joseph tempted by the Devil (depicted as an old man with furled wings) to break off his betrothal, and how he resists that temptation. There are some paintings with him wearing a Jewish hat.

Chronology of Saint Joseph's life in art

Joseph and Joachim, Dürer, 1504

Joseph and Joachim, Dürer, 1504 At work in the Mérode Altarpiece, 1420s, attributed to Robert Campin and his workshop

At work in the Mérode Altarpiece, 1420s, attributed to Robert Campin and his workshop Discovering his wife pregnancy and doubting her faithfulness before being reassured by an angel, Upper Rhenish Master, c. 1430

Discovering his wife pregnancy and doubting her faithfulness before being reassured by an angel, Upper Rhenish Master, c. 1430 Joseph's Dream, Rembrandt, c. 1645

Joseph's Dream, Rembrandt, c. 1645 Marriage to the Virgin, Perugino, c. 1448

Marriage to the Virgin, Perugino, c. 1448 Nativity of Jesus, Marten de Vos 1577

Nativity of Jesus, Marten de Vos 1577 The Adoration of the Magi, Hans Memling, c. 1480

The Adoration of the Magi, Hans Memling, c. 1480 Temple presentation, di Fredi, 1388

Temple presentation, di Fredi, 1388.jpg.webp) Dream of Flight, Daniele Crespi, c. 1625

Dream of Flight, Daniele Crespi, c. 1625 Flight to Egypt, Giotto, 14th century

Flight to Egypt, Giotto, 14th century_excerpt.jpg.webp) Finding in the Temple, Book of Hours, 15th century

Finding in the Temple, Book of Hours, 15th century Death of Joseph, St. Martin's at Florac

Death of Joseph, St. Martin's at Florac Coronation of Joseph, Valdés Leal, c. 1670

Coronation of Joseph, Valdés Leal, c. 1670

Music

Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motet de St Joseph, H.368, for soloists, chorus, and continuo (1690)

See also

- Marriage of the Virgin

- Statue of Saint Joseph, Charles Bridge

- Portal:Catholic Church patron saint archive

Notes

- Domar: the calendrical and liturgical cycle of the Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Church 2003, Armenian Orthodox Theological Research Institute, 2002, p. 530-1.

- Boff, Leonardo (2009). Saint Joseph: The Father of Jesus in a Fatherless Society. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 34. ISBN 9781606080078.

Legal father, because he cohabits with Mary, Jesus' mother. Through this title Mary is spared from false suppositions and Jesus from spurious origins.

- Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 237-238.

- "stjoeshill.org - stjoeshill Resources and Information". ww1.stjoeshill.org.

- "St. Joseph Lutheran Church, Allentown, Pennsylvania". lutherans.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014.

- Thomas H. Kinane (1884). St. Joseph, his life, his virtues [&c.]. A month of March in his honour. p. 214. OCLC 13901748.

- Reverend Archdeacon Kinane. "Section VI - The perpetual virginity os St. Joseph". Saint Joseph: His Life, His Virtues, His Privileges, His Power. Aeterna Press. p. 138. OCLC 972347083. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- "Chaplet and Prayers of the Most Chaste Heart of St. Joseph" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 October 2015.

- P. de Letter, "The Theology of Saint Joseph", The Clergy Monthly, March 1955, JSTOR 27656897

- For the use of the term, see: James J. Davis, A Thomistic Josephology, 1967, University of Montreal, ASIN B0007K3PL4

- "What's the Chronological Order of the New Testament Books?". 2 March 2018.

- "Joseph in the Gospels of Mark and John". osjusa.org.

- Spong, John Shelby. Jesus for the non-religious. HarperCollins. 2007. ISBN 0-06-076207-1.

- Perrotta, Louise B. (2000). Saint Joseph: His Life and His Role in the Church Today. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing. pp. 21, 110–112. ISBN 978-0-87973-573-9.

- Souvay, Charles (1910). "St. Joseph". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Henry Alford: Greek Testament, on Luke 3:23. Alford records that many have thus punctuated the verse, though Alford does not endorse it.

- Vermès 2004, pp. 1–37.

- Vermes, Geza (1981). Jesus the Jew: A Historian's Reading of the Gospels. Philadelphia: First Fortress. p. 20. ISBN 978-1451408805.

- Ironside, Harry A. (2007). Luke. Kregel Academic. p. 73. ISBN 978-0825496653.

- Ryrie, Charles C. (1999). Basic Theology: A Popular Systematic Guide to Understanding Biblical Truth. Moody Publishers. ISBN 978-1575674988.

- Monnickendam, Yifat (2019). "Biblical Law in Greco-Roman Attire: The Case of Levirate Marriage in Late Antique Christian Legal Traditions". Journal of Law and Religion. 34 (2): 136–164. doi:10.1017/jlr.2018.40. S2CID 213399685.

- "Why Are Jesus' Genealogies in Matthew and Luke Different? Was St. Joseph Adopted, too? Spiritual Insights into Adoption". All Roads Lead to Rome. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- Hippo, Augustine. "Sermon on New Testament, par. 7". New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- "techno-". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- Dickson, 47

- Deiss, Lucien (1996). Joseph, Mary, Jesus. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0814622551.

- Fiensy, 68–69

- Fiensy, 75–77

- Landman, Leo (1979). "The Jewish Quarterly Review New Series, Vol. 70, No. 2 (JSTOR)". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 70 (2): 125–128. doi:10.2307/1453874. JSTOR 1453874.

- Ehrman, Bart D. Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins, 2005. ISBN 978-0-06-073817-4

- Crossan, John Dominic. The essential Jesus. Edison: Castle Books. 1998. "Contexts," pp 1–24.

- Theissen, Gerd and Annette Merz. The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Fortress Press. 1998. translated from German (1996 edition)

- Sanders terms it a "minor village." Sanders, E. P. The historical figure of Jesus. Penguin, 1993. p. 104

- Laughlin, 192–194. See also Reed's Chapter 3, pp. 131–134.

- Reed, 114–117, quotation p. 115

- Reed, Chapter 4 in general, pp. 125–131 on the Jewish nature of Sepphoris, and pp. 131–134

- Borgen, Peder Johan; Aune, David Edward; Seland, Torrey; Ulrichsen, Jarl Henning (5 March 2018). Neotestamentica Et Philonica: Studies in Honour of Peder Borgen. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004126107 – via Google Books.

- For example, Dickson, 47

- Vermès 2004, pp. 398–417.

- Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar. The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. 1998. "Birth & Infancy Stories" pp. 497–526.

- Holy Apostles Convent (1989). The Life of the Virgin Mary, the Theotokos. Buena Vista: Holy Apostles Convent and Dormition Skete. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-944359-03-7.

- "Judaism 101: Marriage". www.jewfaq.org.

- "Kiddushin -- Betrothal". www.chabad.org.

- Barclay, William (1 November 1998). The Ten Commandments. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-664-25816-0.

- Hall, James, Hall's Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, p. 178, 1996 (2nd edn.), John Murray, ISBN 0719541476

- Everett Ferguson, Michael P. McHugh, Frederick W. Norris, article "Joseph" in Encyclopedia of early Christianity, Volume 1, p. 629

- Luigi Gambero, "Mary and the fathers of the church: the Blessed Virgin Mary in patristic thought" pp. 35–41

- CHURCH FATHERS: The History of Joseph the Carpenter. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Cyprus), Saint Epiphanius (Bishop of Constantia in; texts), Frank Williams (Specialist in early Christian; Holl, Karl (2013). The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis: De fide. Books II and III. Leiden [u.a.]: BRILL. p. 622. ISBN 978-9004228412.

- College, St. Epiphanius of Cyprus; translated by Young Richard Kim, Calvin (2014). Ancoratus 60:1. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-8132-2591-3. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Williams, translated by Frank (1994). The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis: Books II and III (Sects 47-80, De Fide) in Sect 78:9:6. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 607. ISBN 9789004098985. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Williams, translated by Frank (2013). The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis (Second, revised ed.). Leiden [u.a.]: Brill. p. 36. ISBN 9789004228412. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History, Book III, ch. 11.

- of Salamis, Epiphanius; Williams, Frank (2013). The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis: De fide. Books II and III Sect 78:7,5. BRILL. p. 620. ISBN 978-9004228412. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Celsus as quoted by Origen". www.earlychristianwritings.com.

- Contra Celsum, trans Henry Chadwick, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965)

- The liturgy and time by Irénée Henri Dalmais, Aimé Georges Martimort, Pierre Jounel 1985 ISBN 0-8146-1366-7 page 143

- Holy people of the world: a cross-cultural encyclopedia, Volume 3 by Phyllis G. Jestice 2004 ISBN 1-57607-355-6 page 446

- Bernard of Clairvaux and the shape of monastic thought by M. B. Pranger 1997 ISBN 90-04-10055-5 page 244

- The childhood of Christ by Thomas Aquinas, Roland Potter, 2006 ISBN 0-521-02960-0 pages 110–120

- Aquinas on doctrine by Thomas Gerard Weinandy, John Yocum 2004 ISBN 0-567-08411-6 page 248

- Medieval mothering by John Carmi Parsons, Bonnie Wheeler 1999 ISBN 0-8153-3665-9 page 107

- "Quamquam Pluries (August 15, 1889) | LEO XIII". Vatican website.

- "Sunday - Catholic Magazine". sunday.niedziela.pl.

- Foundations of the Christian way of life by Jacob Prasad 2001 ISBN 88-7653-146-7 page 404

- "Redemptoris Custos (August 15, 1989) | John Paul II". Vatican website.

- Cradle of redeeming love: the theology of the Christmas mystery by John Saward 2002 ISBN 0-89870-886-9 page 230

- Divine likeness: toward a Trinitarian anthropology of the family by Marc Ouellet ISBN 0-8028-2833-7 page 102

- Memorial of Saint Joseph the Worker

- "Tisch". www.clerus.org.

- Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1969), p. 89

- 19 March is observed as the Feast of Saint Joseph, Guardian of Jesus, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod, the Wisconsin Synod, and the Evangelical Lutheran Synod. Some Protestant traditions also celebrate this festival.

- "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 1 December 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-234-7.

- Jankowski, Nicole (18 March 2017). "Move Over, St. Patrick: St. Joseph's Feast Is When Italians Parade: The Salt: NPR". NPR. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- "Non-Stop New York's Italianissimo: La Festa di San Giuseppe NYC-Style".

- Clarkson, Janet (2013). Food History Almanac. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 262. ISBN 978-1442227156.

- "Louisiana Project - St. Joseph's Day Altars". houstonculture.org.

- "Feast of Saint Joseph the Worker | Roman Catholicism | Britannica". www.britannica.com.

- "St. Joseph, Hammer of Communists: The Anti-Communist Origins of the Feast of St. Joseph the Worker". All Roads Lead to Rome. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- Robert Voigt, St. Joseph the Workman in Homiletic & Pastoral Review, Joseph F. Wagner, Inc., New York, NY, 1957, pp. 733–735

- "Pope Francis proclaims "Year of St Joseph" - Vatican News". www.vaticannews.va. Vatican News. 8 December 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- Francis, Pope. Apostolic Letter Patris Corde of the Holy Father Francis on the 150th Anniversary of the proclamation of Saint Joseph as Patron of the Universal Church (8 December 2020). Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- Leonard Foley OFM Saint of the Day, Lives, Lessons, and Feast, (revised by Pat McCloskey OFM), Franciscan Media, ISBN 978-0-86716-887-7

- "Patronages – Year of St. Joseph".

- Mention Your Request Here: The Church's Most Powerful Novenas by Michael Dubruiel, 2000 ISBN 0-87973-341-1 page 154

- Devotions to St. Joseph by Susanna Magdalene Flavius, 2008 ISBN 1-4357-0948-9 pages 5–15

- "Powerful Novena to St. Joseph for Work, Family, Job, Employment, to Sell House". All Roads Lead to Rome. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- Devotions to St. Joseph from The Catholic Prayer Book and Manual of Meditations by Patrick Francis Moran

- Introduction to the Devout Life by St. Francis de Sales ISBN 0-7661-0074-X Kessinger Press 1942 page 297

- The interior castle by Saint Teresa of Ávila, Paulist Press 1979, ISBN 0-8091-2254-5 page 2

- The Story of a Soul by Saint Therese De Lisieux Bibliolife 2008 0554261588 page 94

- Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 0-87973-910-X page 449

- Marcelle Bernstein, The nuns, Collins, London, 1976, p. 84

- Applebome, Peter (16 September 2009). "St. Joseph, Superagent in Real Estate". New York Times. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "The Story Behind Using a St. Joseph Statue to Sell Your House". 16 April 2018.

- Knecht, Friedrich Justus (1910). . A Practical Commentary on Holy Scripture. B. Herder.

- "Sacred Artwork – Year of St. Joseph". yearofstjoseph.org.

- Stracke, Richard. "Saint Joseph: The Iconography ", Christian Iconography Augusta University, 21 June 2021

- Shapiro:6–7

- Finding St. Joseph by Sandra Miesel gives a useful account of the changing views of Joseph in art and generally in Catholicism

- Waldemar Januszczak, "No ordinary Joe", The Sunday Times, December 2003

- Wilson, Carolyn C., St. Joseph in Italian Renaissance Society and Art, Saint Joseph's University Press, 2001, ISBN 9780916101367

- Black, Charlene Villaseñor, Creating the Cult of St. Joseph, Princeton University Press, 2006, ISBN 9780691096315

Sources

- Bauckham, Richard (2015). Jude and the Relatives of Jesus in the Early Church. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781474230476.

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). "Brethren of the Lord". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192802903.

- Ferguson, Everett; Michael P. McHugh, Frederick W. Norris, "Joseph" in Encyclopedia of early Christianity, Volume 1, p. 629

- Crossan, John Dominic. Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. Harpercollins: 1994. ISBN 0-06-061661-X.

- Dickson, John. Jesus: A Short Life, Lion Hudson plc, 2008, ISBN 0-8254-7802-2, ISBN 978-0-8254-7802-4, Internet Archive

- Fiensy, David A., Jesus the Galilean: soundings in a first century life, Gorgias Press LLC, 2007, ISBN 1-59333-313-7, ISBN 978-1-59333-313-3, Google books

- Vermès, Géza (2004). The authentic gospel of Jesus. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-191260-8. OCLC 647043972.

External links

- "Eastern Orthodox Tradition: The Righteous Elder Joseph The Betrothed, And His Repose". swerfes.org. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2006.

- "Holy Righteous Joseph the Betrothed". (Orthodox icon and synaxarion for the Sunday after Nativity)

- "Eastern Orthodox Tradition: The Righteous Elder Joseph The Betrothed, And His Repose". swerfes.org. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2006.

- "Holy Righteous Joseph the Betrothed". (Orthodox icon and synaxarion for the Sunday after Nativity)

- "Saint Joseph, patriarch of Israel and father of Jesus". Archived from the original on 3 May 2006.

- "The Life of St. Joseph, Spouse of the Blessed Virgin Mary and foster-father of Our Lord Jesus Christ".

- "Saint Joseph, in the Encyclopædia Britannica". 2010. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008.

- "The vocation of Saint Joseph". Early Christians. 21 January 2013. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013.

- "Colonnade Statue in St Peter's Square in Rome". stpetersbasilica.info.

- "St Joseph Altar in St Peter's Basilica". stpetersbasilica.info.

- Literature by and about Saint Joseph in the German National Library catalogue

- "Saint Joseph" in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- "Apostolic writing Redemptoris Custos by Pope John Paul II". stjosef.at (in German).

- "Saint Joseph in art". Monumente Online (in German). Archived from the original on 31 December 2015.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)