History of the Catholic Church

The history of the Catholic Church is the formation, events, and historical development of the Catholic Church through time.

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

The tradition of the Catholic Church claims the Catholic Church began with Jesus Christ and his teachings; the Catholic tradition considers that the Catholic Church is a continuation of the early Christian community established by the Disciples of Jesus.[1] The Church considers its bishops to be the successors to Jesus's apostles and the Church's leader, the Bishop of Rome (also known as the Pope), to be the sole successor to Saint Peter[2] who ministered in Rome in the first century AD after his appointment by Jesus as head of the Church.[3][4] By the end of the 2nd century, bishops began congregating in regional synods to resolve doctrinal and policy issues.[5] Historian Eamon Duffy claims that by the 3rd century, the church at Rome might even function as a court of appeal on doctrinal issues.[6]

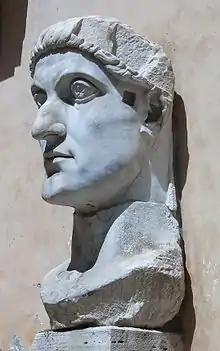

Christianity spread throughout the early Roman Empire, with all persecutions due to conflicts with the pagan state religion. In 313, the persecutions were lessened by the Edict of Milan with the legalization of Christianity by the Emperor Constantine I. In 380, under Emperor Theodosius, Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire by the Edict of Thessalonica, a decree of the Emperor which would persist until the fall of the Western Roman Empire (Western Empire), and later, with the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire), until the Fall of Constantinople. During this time, the period of the Seven Ecumenical Councils, there were considered five primary sees (jurisdictions within the Catholic Church) according to Eusebius: Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria, known as the Pentarchy.

The battles of Toulouse preserved the Christian west against the Umayyad Muslim army, even though Rome itself was ravaged in 850, and Constantinople besieged. In the 11th century, already strained relations between the primarily Greek church in the East, and the Latin church in the West, developed into the East-West Schism, partially due to conflicts over papal authority. The Fourth Crusade, and the sacking of Constantinople by renegade crusaders proved the final breach. Prior to and during the 16th century, the Church engaged in a process of reform and renewal. Reform during the 16th century is known as the Counter-Reformation.[7] In subsequent centuries, Catholicism spread widely across the world despite experiencing a reduction in its hold on European populations due to the growth of Protestantism and also because of religious skepticism during and after the Enlightenment. The Second Vatican Council in the 1960s introduced the most significant changes to Catholic practices since the Council of Trent four centuries before.

Church beginnings

Origins

According to Catholic tradition, the Catholic Church was founded by Jesus Christ.[8] The New Testament records Jesus' activities and teaching, his appointment of the twelve Apostles, and his instructions to them to continue his work.[9][10] The Catholic Church teaches that the coming of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles, in an event known as Pentecost, signaled the beginning of the public ministry of the Church.[11] Catholics hold that Saint Peter was Rome's first bishop and the consecrator of Linus as its next bishop, thus starting the unbroken line which includes the current pontiff, Pope Francis. That is, the Catholic Church maintains the apostolic succession of the Bishop of Rome, the Pope – the successor to Saint Peter.[12]

In the account of the Confession of Peter found in the Gospel of Matthew, it is believed that Christ designates Peter as the "rock" upon which Christ's church will be built.[13][14] While some scholars do state Peter was the first Bishop of Rome,[15][lower-alpha 1] others say that the institution of the papacy is not dependent on the idea that Peter was Bishop of Rome or even on his ever having been in Rome.[16] Many scholars hold that a church structure of plural presbyters/bishops persisted in Rome until the mid-2nd century, when the structure of a single bishop and plural presbyters was adopted,[17][lower-alpha 2] and that later writers retrospectively applied the term "bishop of Rome" to the most prominent members of the clergy in the earlier period and also to Peter himself.[17] On this basis, Oscar Cullmann[19] and Henry Chadwick[20] question whether there was a formal link between Peter and the modern papacy, and Raymond E. Brown says that, while it is anachronistic to speak of Peter in terms of a local bishop of Rome, Christians of that period would have looked on Peter as having "roles that would contribute in an essential way to the development of the role of the papacy in the subsequent church". These roles, Brown says, "contributed enormously to seeing the bishop of Rome, the bishop of the city where Peter died, and where Paul witnessed to the truth of Christ, as the successor of Peter in care for the church universal".[17]

Early organization

Conditions in the Roman Empire facilitated the spread of new ideas. The empire's well-defined network of roads and waterways allowed easier travel, while the Pax Romana made it safe to travel from one region to another. The government had encouraged inhabitants, especially those in urban areas, to learn Greek, and the common language allowed ideas to be more easily expressed and understood.[21] Jesus's apostles gained converts in Jewish communities around the Mediterranean Sea,[22] and over 40 Christian communities had been established by 100.[23] Although most of these were in the Roman Empire, notable Christian communities were also established in Armenia, Iran and along the Indian Malabar Coast.[24][25] The new religion was most successful in urban areas, spreading first among slaves and people of low social standing, and then among aristocratic women.[26]

At first, Christians continued to worship alongside Jewish believers, which historians refer to as Jewish Christianity, but within twenty years of Jesus's death, Sunday was being regarded as the primary day of worship.[27] As preachers such as Paul of Tarsus began converting Gentiles, Christianity began growing away from Jewish practices[22] to establish itself as a separate religion,[28] though the issue of Paul of Tarsus and Judaism is still debated today. To resolve doctrinal differences among the competing factions, sometime around the year 50 the apostles convened the first Church council, the Council of Jerusalem. This council affirmed that Gentiles could become Christians without adopting all of the Mosaic Law.[5] Growing tensions soon led to a starker separation that was virtually complete by the time Christians refused to join in the Bar Kokhba Jewish revolt of 132,[29] however some groups of Christians retained elements of Jewish practice.[30]

According to some historians and scholars, the early Christian Church was very loosely organized, resulting in diverse interpretations of Christian beliefs.[31] In part to ensure a greater consistency in their teachings, by the end of the 2nd century Christian communities had evolved a more structured hierarchy, with a central bishop having authority over the clergy in his city,[32] leading to the development of the Metropolitan bishop. The organization of the Church began to mimic that of the Empire; bishops in politically important cities exerted greater authority over bishops in nearby cities.[33] The churches in Antioch, Alexandria, and Rome held the highest positions.[34] Beginning in the 2nd century, bishops often congregated in regional synods to resolve doctrinal and policy issues.[5] Duffy claims that by the 3rd century, the bishop of Rome began to act as a court of appeals for problems that other bishops could not resolve.[6]

Doctrine was further refined by a series of influential theologians and teachers, known collectively as the Church Fathers.[35] From the year 100 onward, proto-orthodox teachers like Ignatius of Antioch and Irenaeus defined Catholic teaching in stark opposition to other things, such as Gnosticism.[36] Teachings and traditions were consolidated under the influence of theological apologists such as Pope Clement I, Justin Martyr, and Augustine of Hippo.[37]

Persecutions

Unlike most religions in the Roman Empire, Christianity required its adherents to renounce all other gods, a practice adopted from Judaism. Christians' refusal to join pagan celebrations meant they were unable to participate in much of public life, which caused non-Christians–including government authorities–to fear that the Christians were angering the gods and thereby threatening the peace and prosperity of the Empire. In addition, the peculiar intimacy of Christian society and its secrecy about its religious practices spawned rumors that Christians were guilty of incest and cannibalism; the resulting persecutions, although usually local and sporadic, were a defining feature of Christian self-understanding until Christianity was legalized in the 4th century.[38][39] A series of more centrally organized persecutions of Christians emerged in the late 3rd century, when emperors decreed that the Empire's military, political, and economic crises were caused by angry gods. All residents were ordered to give sacrifices or be punished.[40] Jews were exempted as long as they paid the Jewish Tax. Estimates of the number of Christians who were executed ranges from a few hundred to 50,000.[41] Many fled[42] or renounced their beliefs. Disagreements over what role, if any, these apostates should have in the Church led to the Donatist and Novatianist schisms.[43]

In spite of these persecutions, evangelization efforts persisted, leading to the Edict of Milan which legalized Christianity in 313.[44] By 380, Christianity had become the state religion of the Roman Empire.[45] Religious philosopher Simone Weil wrote: "By the time of Constantine, the state of apocalyptic expectation must have worn rather thin. [The imminent coming of Christ, expectation of the Last Day – constituted 'a very great social danger']. Besides, the spirit of the old law, so widely separated from all mysticism, was not so very different from the Roman spirit itself. Rome could come to terms with the God of Hosts."[46]

Late antiquity

When Constantine became emperor of the Western Roman Empire in 312, he attributed his victory to the Christian God. Many soldiers in his army were Christians, and his army was his base of power. With Licinius, (Eastern Roman emperor), he issued the Edict of Milan which mandated toleration of all religions in the empire. The edict had little effect on the attitudes of the people.[47] New laws were crafted to codify some Christian beliefs and practices.[lower-alpha 3][48] Constantine's biggest effect on Christianity was his patronage. He gave large gifts of land and money to the Church and offered tax exemptions and other special legal status to ecclesiastical property and personnel.[49] These gifts and later ones combined to make the Church the largest landowner in the West by the 6th century.[50] Many of these gifts were funded through severe taxation of pagan cults.[49] Some pagan cults were forced to disband for lack of funds; when this happened the Church took over the cult's previous role of caring for the poor.[51] In a reflection of their increased standing in the Empire, clergy began to adopt the dress of the royal household, including the cope.[52]

During Constantine's reign, approximately half of those who identified themselves as Christian did not subscribe to the mainstream version of the faith.[53] Constantine feared that disunity would displease God and lead to trouble for the Empire, so he took military and judicial measures to eliminate some sects.[54] To resolve other disputes, Constantine began the practice of calling ecumenical councils to determine binding interpretations of Church doctrine.[55]

Decisions made at the Council of Nicea (325) about the divinity of Christ led to a schism; the new religion, Arianism flourished outside the Roman Empire.[56] Partially to distinguish themselves from Arians, Catholic devotion to Mary became more prominent. This led to further schisms.[57][58]

In 380, mainstream Christianity–as opposed to Arianism–became the official religion of the Roman Empire.[59] Christianity became more associated with the Empire, resulting in persecution for Christians living outside of the empire, as their rulers feared Christians would revolt in favor of the Emperor.[60] In 385, this new legal authority of the Church resulted in the first use of capital punishment being pronounced as a sentence upon a Christian 'heretic', namely Priscillian.[61]

During this period, the Bible as it has come down to the 21st century was first officially laid out in Church Councils or Synods through the process of official 'canonization'. Prior to these Councils or Synods, the Bible had already reached a form that was nearly identical to the form in which it is now found. According to some accounts, in 382 the Council of Rome first officially recognized the Biblical canon, listing the accepted books of the Old and New Testament, and in 391 the Vulgate Latin translation of the Bible was made.[62] Other accounts list the Council of Carthage of 397 as the Council that finalized the Biblical canon as it is known today.[63] The Council of Ephesus in 431 clarified the nature of Jesus' incarnation, declaring that he was both fully man and fully God.[64] Two decades later, the Council of Chalcedon solidified Roman papal primacy which added to continuing breakdown in relations between Rome and Constantinople, the seat of the Eastern Church.[65] Also sparked were the Monophysite disagreements over the precise nature of the incarnation of Jesus which led to the first of the various Oriental Orthodox Churches breaking away from the Catholic Church.[66]

Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, trinitarian Christianity competed with Arian Christianity for the conversion of the barbarian tribes.[67] The 496 conversion of Clovis I, pagan king of the Franks, saw the beginning of a steady rise of the faith in the West.[68]

In 530, Saint Benedict wrote his Rule of St Benedict as a practical guide for monastic community life. Its message spread to monasteries throughout Europe.[69] Monasteries became major conduits of civilization, preserving craft and artistic skills while maintaining intellectual culture within their schools, scriptoria and libraries. They functioned as agricultural, economic and production centers as well as a focus for spiritual life.[70] During this period the Visigoths and Lombards moved away from Arianism for Catholicism.[68] Pope Gregory the Great played a notable role in these conversions and dramatically reformed the ecclesiastical structures and administration which then launched renewed missionary efforts.[71] Missionaries such as Augustine of Canterbury, who was sent from Rome to begin the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons, and, coming the other way in the Hiberno-Scottish mission, Saints Colombanus, Boniface, Willibrord, Ansgar and many others took Christianity into northern Europe and spread Catholicism among the Germanic, and Slavic peoples, and reached the Vikings and other Scandinavians in later centuries.[72] The Synod of Whitby of 664, though not as decisive as sometimes claimed, was an important moment in the reintegration of the Celtic Church of the British Isles into the Roman hierarchy, after having been effectively cut off from contact with Rome by the pagan invaders. And in Italy, the 728 Donation of Sutri and the 756 Donation of Pepin left the papacy in charge a sizable kingdom. Further consolidating the papal position over the western part of the former Roman Empire, the Donation of Constantine was probably forged during the 8th century.

In the early 8th century, Byzantine iconoclasm became a major source of conflict between the Eastern and Western parts of the Church. Byzantine emperors forbade the creation and veneration of religious images, as violations of the Ten Commandments. Other major religions in the East such as Judaism and Islam had similar prohibitions. Pope Gregory III vehemently disagreed.[73] A new Empress Irene siding with the pope, called for an Ecumenical Council. In 787, the fathers of the Second Council of Nicaea "warmly received the papal delegates and his message".[74] At the conclusion, 300 bishops, who were led by the representatives of Pope Hadrian I[75] "adopted the Pope's teaching",[74] in favor of icons.

With the coronation of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III in 800, his new title as Patricius Romanorum, and the handing over of the keys to the Tomb of Saint Peter, the papacy had acquired a new protector in the West. This freed the pontiffs to some degree from the power of the emperor in Constantinople but also led to a schism, because the emperors and patriarchs of Constantinople interpreted themselves as the true descendants of the Roman Empire dating back to the beginnings of the Church.[76] Pope Nicholas I had refused to recognize Patriarch Photios I of Constantinople, who in turn had attacked the pope as a heretic, because he kept the filioque in the creed, which referred to the Holy Spirit emanating from God the Father and the Son. The papacy was strengthened through this new alliance, which in the long term created a new problem for the Popes, when in the Investiture controversy succeeding emperors sought to appoint bishops and even future popes.[77][78] After the disintegration of the Carolingian Empire and repeated incursions of Islamic forces into Italy, the papacy, without any protection, entered a phase of major weakness.[79]

High Middle Ages

The Cluniac reform of monasteries that began in 910 placed abbots under the direct control of the pope rather than the secular control of feudal lords, thus eliminating a major source of corruption. This sparked a great monastic renewal.[80] Monasteries, convents and cathedrals still operated virtually all schools and libraries, and often functioned as credit establishments promoting economic growth.[81][82] After 1100, some older cathedral schools split into lower grammar schools and higher schools for advanced learning. First in Bologna, then at Paris and Oxford, many of these higher schools developed into universities and became the direct ancestors of modern Western institutions of learning.[83] It was here where notable theologians worked to explain the connection between human experience and faith.[84] The most notable of these theologians, Thomas Aquinas, produced Summa Theologica, a key intellectual achievement in its synthesis of Aristotelian thought and the Gospel.[84] Monastic contributions to western society included the teaching of metallurgy, the introduction of new crops, the invention of musical notation and the creation and preservation of literature.[83]

During the 11th century, the East–West schism permanently divided Christianity.[85] It arose over a dispute on whether Constantinople or Rome held jurisdiction over the church in Sicily and led to mutual excommunications in 1054.[85] The Western (Latin) branch of Christianity has since become known as the Catholic Church, while the Eastern (Greek) branch became known as the Orthodox Church.[86][87] The Second Council of Lyon (1274) and the Council of Florence (1439) both failed to heal the schism.[88] Some Eastern churches have since reunited with the Catholic Church, and others claim never to have been out of communion with the pope.[87][89] Officially, the two churches remain in schism, although excommunications were mutually lifted in 1965.[90]

The 11th century saw the Investiture controversy between Emperor and Pope over the right to make church appointments, the first major phase of the struggle between Church and state in medieval Europe. The Papacy were the initial victors, but as Italians divided between Guelphs and Ghibellines in factions that were often passed down through families or states until the end of the Middle Ages, the dispute gradually weakened the Papacy, not least by drawing it into politics. The Church also attempted to control, or exact a price for, most marriages among the great by prohibiting, in 1059, marriages involving consanguinity (blood kin) and affinity (kin by marriage) to the seventh degree of relationship. Under these rules, almost all great marriages required a dispensation. The rules were relaxed to the fourth degree in 1215 (now only the first degree is prohibited by the Church – a man cannot marry his stepdaughter, for example).

Pope Urban II launched the First Crusade in 1095 when he received an appeal from Byzantine emperor Alexius I to help ward off a Turkish invasion.[91] Urban further believed that a Crusade might help bring about reconciliation with Eastern Christianity.[92][93] Fueled by reports of Muslim atrocities against Christians,[94] the series of military campaigns known as the Crusades began in 1096. They were intended to return the Holy Land to Christian control. The goal was not permanently realized, and episodes of brutality committed by the armies of both sides left a legacy of mutual distrust between Muslims and Western and Eastern Christians.[95] The sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade left Eastern Christians embittered, despite the fact that Pope Innocent III had expressly forbidden any such attack.[96] In 2001, Pope John Paul II apologized to the Orthodox Christians for the sins of Catholics including the sacking of Constantinople in 1204.[97]

Two new orders of architecture emerged from the Church of this era. The earlier Romanesque style combined massive walls, rounded arches and ceilings of masonry. To compensate for the absence of large windows, interiors were brightly painted with scenes from the Bible and the lives of the saints. Later, the Basilique Saint-Denis marked a new trend in cathedral building when it utilized Gothic architecture.[98] This style, with its large windows and high, pointed arches, improved lighting and geometric harmony in a manner that was intended to direct the worshiper's mind to God who "orders all things".[98] In other developments, the 12th century saw the founding of eight new monastic orders, many of them functioning as Military Knights of the Crusades.[99] Cistercian monk Bernard of Clairvaux exerted great influence over the new orders and produced reforms to ensure purity of purpose.[99] His influence led Pope Alexander III to begin reforms that would lead to the establishment of canon law.[100] In the following century, new mendicant orders were founded by Francis of Assisi and Dominic de Guzmán which brought consecrated religious life into urban settings.[101]

12th-century France witnessed the growth of Catharism in Languedoc. It was in connection with the struggle against this heresy that the Inquisition originated. After the Cathars were accused of murdering a papal legate in 1208, Pope Innocent III declared the Albigensian Crusade.[102] Abuses committed during the crusade caused Innocent III to informally institute the first papal inquisition to prevent future massacres and root out the remaining Cathars.[103][104] Formalized under Gregory IX, this Medieval inquisition executed an average of three people per year for heresy at its height.[104][105] Over time, other inquisitions were launched by the Church or secular rulers to prosecute heretics, to respond to the threat of Moorish invasion or for political purposes.[106] The accused were encouraged to recant their heresy and those who did not could be punished by penance, fines, imprisonment or execution by burning.[106][107]

| Part of a series on |

| Ecumenical councils of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| 4th–5th centuries |

|

| 6th–9th centuries |

|

| 12th–14th centuries |

|

| 15th–16th centuries |

|

| 19th–20th centuries |

|

|

A growing sense of church-state conflicts marked the 14th century. To escape instability in Rome, Clement V in 1309 became the first of seven popes to reside in the fortified city of Avignon in southern France[108] during a period known as the Avignon Papacy. The papacy returned to Rome in 1378 at the urging of Catherine of Siena and others who felt the See of Peter should be in the Roman church.[109][110] With the death of Pope Gregory XI later that year, the papal election was disputed between supporters of Italian and French-backed candidates leading to the Western Schism. For 38 years, separate claimants to the papal throne sat in Rome and Avignon. Efforts at resolution further complicated the issue when a third compromise pope was elected in 1409.[111] The matter was finally resolved in 1417 at the Council of Constance where the cardinals called upon all three claimants to the papal throne to resign, and held a new election naming Martin V pope.[111]

Renaissance and reforms

Discoveries and missionaries

Through the late 15th and early 16th centuries, European missionaries and explorers spread Catholicism to the Americas, Asia, Africa and Oceania. Pope Alexander VI, in the papal bull Inter caetera, awarded colonial rights over most of the newly discovered lands to Spain and Portugal.[112] Under the patronato system, state authorities controlled clerical appointments and no direct contact was allowed with the Vatican.[113] In December 1511, the Dominican friar Antonio de Montesinos openly rebuked the Spanish authorities governing Hispaniola for their mistreatment of the American natives, telling them "... you are in mortal sin ... for the cruelty and tyranny you use in dealing with these innocent people".[114][115][116] King Ferdinand enacted the Laws of Burgos and Valladolid in response. Enforcement was lax, and while some blame the Church for not doing enough to liberate the Indians, others point to the Church as the only voice raised on behalf of indigenous peoples.[117] The issue resulted in a crisis of conscience in 16th-century Spain.[118][116] An outpouring of self-criticism and philosophical reflection among Catholic theologians, most notably Francisco de Vitoria, led to debate on the nature of human rights[116] and the birth of modern international law.[119][120]

In 1521, through the leadership and preaching of the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, the first Catholics were baptized in what became the first Christian nation in Southeast Asia, the Philippines.[121] The following year, Franciscan missionaries arrived in what is now Mexico, and sought to convert the Indians and to provide for their well-being by establishing schools and hospitals. They taught the Indians better farming methods, and easier ways of weaving and making pottery. Because some people questioned whether the Indians were truly human and deserved baptism, Pope Paul III in the papal bull Veritas Ipsa or Sublimis Deus (1537) confirmed that the Indians were deserving people.[122][123] Afterward, the conversion effort gained momentum.[124] Over the next 150 years, the missions expanded into southwestern North America.[125] The native people were legally defined as children, and priests took on a paternalistic role, often enforced with corporal punishment.[126] Elsewhere, in India, Portuguese missionaries and the Spanish Jesuit Francis Xavier evangelized among non-Christians and a Christian community which claimed to have been established by Thomas the Apostle.[127]

European Renaissance

In Europe, the Renaissance marked a period of renewed interest in ancient and classical learning. It also brought a re-examination of accepted beliefs. Cathedrals and churches had long served as picture books and art galleries for millions of the uneducated. The stained glass windows, frescoes, statues, paintings and panels retold the stories of the saints and of biblical characters. The Church sponsored great Renaissance artists like Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, who created some of the world's most famous artworks.[128] Although Church leaders were able to harness Renaissance humanism inspired arts into their overall effort, there were also conflicts between clerics and humanists, such as during the heresy trials of Johann Reuchlin. In 1509, a well known scholar of the age, Erasmus, wrote The Praise of Folly, a work which captured a widely held unease about corruption in the Church.[129] The Papacy itself was questioned by conciliarism expressed in the councils of Constance and the Basel. Real reforms during these ecumenical councils and the Fifth Lateran Council were attempted several times but thwarted. They were seen as necessary but did not succeed in large measure because of internal feuds,[130] ongoing conflicts with the Ottoman Empire and Saracenes[130] and the simony and nepotism practiced in the Renaissance Church of the 15th and early 16th centuries.[131] As a result, rich, powerful and worldly men like Roderigo Borgia (Pope Alexander VI) were able to win election to the papacy.[131][132]

Reformation era wars

The Fifth Lateran Council issued some but only minor reforms in March 1517. A few months later, on 31 October 1517, Martin Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses in public, hoping to spark debate.[133][134] His theses protested key points of Catholic doctrine as well as the sale of indulgences.[133][134] Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin, and others also criticized Catholic teachings. These challenges, supported by powerful political forces in the region, developed into the Protestant Reformation.[135][136] During this era, many people emigrated from their homes to areas which tolerated or practiced their faith, although some lived as crypto-Protestants or Nicodemites.

In Germany, the Reformation led to war between the Protestant Schmalkaldic League and the Catholic Emperor Charles V. The first nine-year war ended in 1555 but continued tensions produced a far graver conflict, the Thirty Years' War, which broke out in 1618.[137] In the Netherlands, the wars of the Counter-Reformation were the Dutch Revolt and the Eighty Years' War, part of which was the War of the Jülich Succession also including northwestern Germany. The Cologne War (1583–89) was a conflict between Protestant and Catholic factions which devastated the Electorate of Cologne. After the archbishop ruling the area converted to Protestantism, Catholics elected another archbishop, Ernst of Bavaria, and successfully defeated him and his allies.

In France, a series of conflicts termed the French Wars of Religion was fought from 1562 to 1598 between the Huguenots and the forces of the French Catholic League. A series of popes sided with and became financial supporters of the Catholic League.[138] This ended under Pope Clement VIII, who hesitantly accepted King Henry IV's 1598 Edict of Nantes, which granted civil and religious toleration to Protestants.[137][138] In 1565, several hundred Huguenot shipwreck survivors surrendered to the Spanish in Florida, believing they would be treated well. Although a Catholic minority in their party was spared, all of the rest were executed for heresy, with active clerical participation.[139]

England

.jpg.webp)

The English Reformation was ostensibly based on Henry VIII's desire for annulment of his marriage with Catherine of Aragon, and was initially more of a political, and later a theological dispute.[141] The Acts of Supremacy made the English monarch head of the English church thereby establishing the Church of England. Then, beginning in 1536, some 825 monasteries throughout England, Wales and Ireland were dissolved and Catholic churches were confiscated.[142][143] When he died in 1547 all monasteries, friaries, convents of nuns and shrines were destroyed or dissolved.[143][144] Mary I of England reunited the Church of England with Rome and, against the advice of the Spanish ambassador, persecuted Protestants during the Marian Persecutions.[145][146]

After some provocation, the following monarch, Elizabeth I enforced the Act of Supremacy. This prevented Catholics from becoming members of professions, holding public office, voting or educating their children.[145][147] Executions of Catholics and dissenting Protestants under Elizabeth I, who reigned much longer, then surpassed the Marian persecutions[145] and persisted under subsequent English monarchs.[148] Elizabeth I also executed other Penal laws were also enacted in Ireland[149] but were less effective than in England.[145][150] In part because the Irish people associated Catholicism with nationhood and national identity, they resisted persistent English efforts to eliminate the Catholic Church.[145][150]

Council of Trent

Historian Diarmaid MacCulloch, in his book The Reformation, A History noted that through all the slaughter of the Reformation era emerged the valuable concept of religious toleration and an improved Catholic Church[151] which responded to doctrinal challenges and abuses highlighted by the Reformation at the Council of Trent (1545–1563). The council became the driving-force of the Counter-Reformation, and reaffirmed central Catholic doctrines such as transubstantiation, and the requirement for love and hope as well as faith to attain salvation.[152] It also reformed many other areas of importance to the Church, most importantly by improving the education of the clergy and consolidating the central jurisdiction of the Roman Curia.[7][152][153]

The decades after the council saw an intellectual dispute between the Lutheran Martin Chemnitz and the Catholic Diogo de Payva de Andrada over whether certain statements matched the teachings of the Church Fathers and Scripture or not. The criticisms of the Reformation were among factors that sparked new religious orders including the Theatines, Barnabites and Jesuits, some of which became the great missionary orders of later years.[154] Spiritual renewal and reform were inspired by many new saints like Teresa of Avila, Francis de Sales and Philip Neri whose writings spawned distinct schools of spirituality within the Church (Oratorians, Carmelites, Salesian), etc.[155] Improvement to the education of the laity was another positive effect of the era, with a proliferation of secondary schools reinvigorating higher studies such as history, philosophy and theology.[156] To popularize Counter-Reformation teachings, the Church encouraged the Baroque style in art, music and architecture. Baroque religious expression was stirring and emotional, created to stimulate religious fervor.[157]

Elsewhere, Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier introduced the Catholic Church in Japan, and by the end of the 16th century tens of thousands of Japanese adhered. Church growth came to a halt in 1597 under the Shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi who, in an effort to isolate the country from foreign influences, launched a severe persecution of Christians.[158] Japanese were forbidden to leave the country and Europeans were forbidden to enter. Despite this, a minority Christian population survived into the 19th century when Japan opened more to outside influence, and they continue to the present day.[158][159]

Baroque, Enlightenment and revolutions

Marian devotions

The Council of Trent generated a revival of religious life and Marian devotions in the Catholic Church. During the Reformation, the Church had defended its Marian beliefs against Protestant views. At the same time, the Catholic world was engaged in ongoing Ottoman Wars in Europe against Turkey which were fought and won under the auspices of the Virgin Mary. The victory at the Battle of Lepanto (1571) was accredited to her "and signified the beginning of a strong resurgence of Marian devotions, focusing especially on Mary, the Queen of Heaven and Earth and her powerful role as mediatrix of many graces".[160] The Colloquium Marianum, an elite group, and the Sodality of Our Lady based their activities on a virtuous life, free of cardinal sins.

Pope Paul V and Gregory XV ruled in 1617 and 1622 to be inadmissible to state, that the virgin was conceived non-immaculate. Supporting the belief that the virgin Mary, in the first instance of her conception was preserved free from all stain of original sin (aka Immaculate Conception) Alexander VII declared in 1661, that the soul of Mary was free from original sin. Pope Clement XI ordered the feast of the Immaculata for the whole Church in 1708. The feast of the Rosary was introduced in 1716, the feast of the Seven Sorrows in 1727. The Angelus prayer was strongly supported by Pope Benedict XIII in 1724 and by Pope Benedict XIV in 1742.[161] Popular Marian piety was even more colourful and varied than ever before: Numerous Marian pilgrimages, Marian Salve devotions, new Marian litanies, Marian theatre plays, Marian hymns, Marian processions. Marian fraternities, today mostly defunct, had millions of members.[162]

.jpeg.webp)

Enlightenment secularism

The Enlightenment constituted a new challenge of the Church. Unlike the Protestant Reformation, which questioned certain Christian doctrines, the enlightenment questioned Christianity as a whole. Generally, it elevated human reason above divine revelation and down-graded religious authorities such as the papacy based on it.[163] Parallel the Church attempted to fend off Gallicanism and Councilarism, ideologies which threatened the papacy and structure of the Church.[164]

Toward the latter part of the 17th century, Pope Innocent XI viewed the increasing Turkish attacks against Europe, which were supported by France, as the major threat for the Church. He built a Polish-Austrian coalition for the Turkish defeat at Vienna in 1683. Scholars have called him a saintly pope because he reformed abuses by the Church, including simony, nepotism and the lavish papal expenditures that had caused him to inherit a papal debt of 50,000,000 scudi. By eliminating certain honorary posts and introducing new fiscal policies, Innocent XI was able to regain control of the church's finances.[165] Innocent X and Clement XI battled Jansenism and Gallicanism, which supported Conciliarism, and rejected papal primacy, demanding special concessions for the Church in France. This weakened the Church's ability to respond to gallicanist thinkers such as Denis Diderot, who challenged fundamental doctrines of the Church.[166]

In 1685 gallicanist King Louis XIV of France issued the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, ending a century of religious toleration. France forced Catholic theologians to support conciliarism and deny Papal infallibility. The king threatened Pope Innocent XI with a general council and a military take-over of the Papal state.[167] The absolute French State used Gallicanism to gain control of virtually all major Church appointments as well as many of the Church's properties.[165][168] State authority over the Church became popular in other countries as well. In Belgium and Germany, Gallicanism appeared in the form of Febronianism, which rejected papal prerogatives in an equal fashion.[169] Emperor Joseph II of Austria (1780–1790) practiced Josephinism by regulating Church life, appointments, and massive confiscation of Church properties.[169] The 18th century is also the time of the Catholic Enlightenment, a multi-faceted reform movement.[170]

Church in North America

In what is now the Western United States, the Catholic Church expanded its missionary activity but, until the 19th century, had to work in conjunction with the Spanish crown and military.[171] Junípero Serra, the Franciscan priest in charge of this effort, founded a series of missions and presidios in California which became important economic, political, and religious institutions.[172] These missions brought grain, cattle and a new political and religious order to the Indian tribes of California. Coastal and overland routes were established from Mexico City and mission outposts in Texas and New Mexico that resulted 13 major California missions by 1781. European visitors brought new diseases that killed off a third of the native population.[173] Mexico shut down the missions in the 1820s and sold off the lands. Only in the 19th century, after the breakdown of most Spanish and Portuguese colonies, was the Vatican able to take charge of Catholic missionary activities through its Propaganda Fide organization.[174]

Church in South America

During this period the Church faced colonial abuses from the Portuguese and Spanish governments. In South America, the Jesuits protected native peoples from enslavement by establishing semi-independent settlements called reductions. Pope Gregory XVI, challenging Spanish and Portuguese sovereignty, appointed his own candidates as bishops in the colonies, condemned slavery and the slave trade in 1839 (papal bull In supremo apostolatus), and approved the ordination of native clergy in spite of government racism.[175]

Jesuits in India

Christianity in India has a tradition of St. Thomas establishing the faith in Kerala. They are called St. Thomas Christians. The community was very small until the Jesuit Francis Xavier (1502–1552) began missionary work. Roberto de Nobili (1577–1656), a Tuscan Jesuit missionary to Southern India followed in his path. He pioneered inculturation, adopting many Brahmin customs which were not, in his opinion, contrary to Christianity. He lived like a Brahmin, learned Sanskrit, and presented Christianity as a part of Indian beliefs, not identical with the Portuguese culture of the colonialists. He permitted the use of all customs, which in his view did not directly contradict Christian teachings. By 1640 there were 40 000 Christians in Madurai alone. In 1632, Pope Gregory XV gave permission for this approach. But strong anti-Jesuit sentiments in Portugal, France, and even in Rome, resulted in a reversal. This ended the successful Catholic missions in India.[176] On 12 September 1744, Benedict XIV forbade the so-called Malabar rites in India, with the result that leading Indian castes, who wanted to adhere to their traditional cultures, turned away from the Catholic Church.[177][178]

French Revolution

The anti-clericalism of the French Revolution saw the wholesale nationalisation of church property and attempts to establish a state-run church. Large numbers of priests refused to take an oath of compliance to the National Assembly, leading to the Church being outlawed and replaced by a new religion of the worship of "Reason" but it never gained popularity. In this period, all monasteries were destroyed, 30,000 priests were exiled and hundreds more were killed.[179][180] When Pope Pius VI sided against the revolution in the First Coalition, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Italy. The 82-year-old pope was taken as a prisoner to France in February 1798 and soon died. To win popular support for his rule, Napoleon re-established the Catholic Church in France through the Concordat of 1801. The church lands were never returned, however the priests and other religious were given salaries by the government, which maintained church properties through tax revenues. Catholics were allowed to continue some of their schools. The end of the Napoleonic wars, signaled by the Congress of Vienna, brought Catholic revival and the return of the Papal States to the pope; the Jesuits were restored.[181][182]

19th-century France

France remained basically Catholic. The census of 1872 counted 36 million people, of whom 35.4 million were listed as Catholics, 600,000 as Protestants, 50,000 as Jews and 80,000 as freethinkers. The Revolution failed to destroy the Catholic Church, and Napoleon's concordat of 1801 restored its status. The return of the Bourbons in 1814 brought back many rich nobles and landowners who supported the Church, seeing it as a bastion of conservatism and monarchism. However the monasteries with their vast land holdings and political power were gone; much of the land had been sold to urban entrepreneurs who lacked historic connections to the land and the peasants. Few new priests were trained in the 1790–1814 period, and many left the church. The result was that the number of parish clergy plunged from 60,000 in 1790 to 25,000 in 1815, many of them elderly. Entire regions, especially around Paris, were left with few priests. On the other hand, some traditional regions held fast to the faith, led by local nobles and historic families.[183] The comeback was slow—very slow in the larger cities and industrial areas. With systematic missionary work and a new emphasis on liturgy and devotions to the Virgin Mary, plus support from Napoleon III, there was a comeback. In 1870 there were 56,500 priests, representing a much younger and more dynamic force in the villages and towns, with a thick network of schools, charities and lay organizations.[184] Conservative Catholics held control of the national government, 1820–1830, but most often played secondary political roles or had to fight the assault from republicans, liberals, socialists and seculars.[185][186]

Third Republic 1870–1940

Throughout the lifetime of the Third Republic there were battles over the status of the Catholic Church. The French clergy and bishops were closely associated with the Monarchists and many of its hierarchy were from noble families. Republicans were based in the anticlerical middle class who saw the Church's alliance with the monarchists as a political threat to republicanism, and a threat to the modern spirit of progress. The Republicans detested the church for its political and class affiliations; for them, the church represented outmoded traditions, superstition and monarchism. The Republicans were strengthened by Protestant and Jewish support. Numerous laws were passed to weaken the Catholic Church. In 1879, priests were excluded from the administrative committees of hospitals and of boards of charity; in 1880, new measures were directed against the religious congregations; from 1880 to 1890 came the substitution of lay women for nuns in many hospitals. Napoleon's 1801 Concordat continued in operation but in 1881, the government cut off salaries to priests it disliked.[187]

The 1882 school laws of Republican Jules Ferry set up a national system of public schools that taught strict puritanical morality but no religion.[188] For a while privately funded Catholic schools were tolerated. Civil marriage became compulsory, divorce was introduced and chaplains were removed from the army.[189]

When Leo XIII became pope in 1878 he tried to calm Church-State relations. In 1884 he told French bishops not to act in a hostile manner to the State. In 1892 he issued an encyclical advising French Catholics to rally to the Republic and defend the Church by participating in Republican politics. This attempt at improving the relationship failed. Deep-rooted suspicions remained on both sides and were inflamed by the Dreyfus Affair. Catholics were for the most part anti-dreyfusard. The Assumptionists published anti-Semitic and anti-republican articles in their journal La Croix. This infuriated Republican politicians, who were eager to take revenge. Often they worked in alliance with Masonic lodges. The Waldeck-Rousseau Ministry (1899–1902) and the Combes Ministry (1902–05) fought with the Vatican over the appointment of bishops. Chaplains were removed from naval and military hospitals (1903–04), and soldiers were ordered not to frequent Catholic clubs (1904). Combes as Prime Minister in 1902, was determined to thoroughly defeat Catholicism. He closed down all parochial schools in France. Then he had parliament reject authorisation of all religious orders. This meant that all fifty four orders were dissolved and about 20,000 members immediately left France, many for Spain.[190] In 1905 the 1801 Concordat was abrogated; Church and State were finally separated. All Church property was confiscated. Public worship was given over to associations of Catholic laymen who controlled access to churches. In practise, Masses and rituals continued. The Church was badly hurt and lost half its priests. In the long run, however, it gained autonomy—for the State no longer had a voice in choosing bishops and Gallicanism was dead.[191]

Africa

At the end of the 19th century, Catholic missionaries followed colonial governments into Africa and built schools, hospitals, monasteries and churches.[192] They enthusiastically supported the colonial administration of the French Congo, which forced the native populations of both territories to engage in large-scale forced labour, enforced through summary execution and mutilation. Catholic missionaries in the French Congo tried to prevent the French central government from stopping these atrocities [193]

Industrial age

First Vatican Council

Before the council, in 1854 Pope Pius IX with the support of the overwhelming majority of Catholic Bishops, whom he had consulted between 1851 and 1853, proclaimed the dogma of the Immaculate Conception.[194] Eight years earlier, in 1846, the Pope had granted the unanimous wish of the bishops from the United States, and declared the Immaculata the patron of the US.[195]

During First Vatican Council, some 108 council fathers requested to add the words "Immaculate Virgin" to the Hail Mary.[196] Some fathers requested the dogma of the Immaculate Conception be included in the Creed of the Church, which was opposed by Pius IX[197] Many French Catholics wished the dogmatization of Papal infallibility and the assumption of Mary by the ecumenical council.[198] During Vatican One, nine mariological petitions favoured a possible assumption dogma, which however was strongly opposed by some council fathers, especially from Germany. In 1870, the First Vatican Council affirmed the doctrine of papal infallibility when exercised in specifically defined pronouncements.[199][200] Controversy over this and other issues resulted in a very small breakaway movement called the Old Catholic Church.[201]

Social teachings

The Industrial Revolution brought many concerns about the deteriorating working and living conditions of urban workers. Influenced by the German Bishop Wilhelm Emmanuel Freiherr von Ketteler, in 1891 Pope Leo XIII published the encyclical Rerum novarum, which set in context Catholic social teaching in terms that rejected socialism but advocated the regulation of working conditions. Rerum novarum argued for the establishment of a living wage and the right of workers to form trade unions.[202]

Quadragesimo anno was issued by Pope Pius XI, on 15 May 1931, 40 years after Rerum novarum. Unlike Leo, who addressed mainly the condition of workers, Pius XI concentrated on the ethical implications of the social and economic order. He called for the reconstruction of the social order based on the principle of solidarity and subsidiarity.[203] He noted major dangers for human freedom and dignity, arising from unrestrained capitalism and totalitarian communism.

The social teachings of Pope Pius XII repeat these teachings, and apply them in greater detail not only to workers and owners of capital, but also to other professions such as politicians, educators, house-wives, farmers, bookkeepers, international organizations, and all aspects of life including the military. Going beyond Pius XI, he also defined social teachings in the areas of medicine, psychology, sport, television, science, law and education. There is virtually no social issue, which Pius XII did not address and relate to the Christian faith.[204] He was called "the Pope of Technology, for his willingness and ability to examine the social implications of technological advances. The dominant concern was the continued rights and dignity of the individual. With the beginning of the space age at the end of his pontificate, Pius XII explored the social implications of space exploration and satellites on the social fabric of humanity asking for a new sense of community and solidarity in light of existing papal teachings on subsidiarity.[205]

Role of women's institutes

Catholic women have played a prominent role in providing education and health services in keeping with Catholic social teaching. Ancient orders like the Carmelites had engaged in social work for centuries.[206] The 19th century saw a new flowering of institutes for women, dedicated to the provision of health and education services – of these the Salesian Sisters of Don Bosco, Claretian Sisters and Franciscan Missionaries of Mary became among the largest Catholic women's religious institutes of all.[207]

The Sisters of Mercy was founded by Catherine McAuley in Ireland in 1831, and her nuns went on to establish hospitals and schools across the world.[208] The Little Sisters of the Poor was founded in the mid-19th century by Saint Jeanne Jugan near Rennes, France, to care for the many impoverished elderly who lined the streets of French towns and cities.[209][210] In Britain's Australian colonies, Australia's first canonized Saint, Mary MacKillop, co-founded the Sisters of St. Joseph of the Sacred Heart as an educative religious institute for the poor in 1866, going on to establish schools, orphanages and refuges for the needy.[211] In 1872, the Salesian Sisters of Don Bosco (also called Daughters of Mary Help of Christians) was founded by Maria Domenica Mazzarello. The teaching order was to become the modern world's largest institute for women, with around 14,000 members in 2012.[207] Saint Marianne Cope opened and operated some of the first general hospitals in the United States, instituting cleanliness standards which influenced the development of America's modern hospital system.[212] Also in the United States, Saint Katharine Drexel founded Xavier University of Louisiana to assist African and Native Americans.[213]

Mariology

.jpg.webp)

Popes have always highlighted the inner link between the Virgin Mary as Mother of God and the full acceptance of Jesus Christ as Son of God.[214][215] Since the 19th century, they were highly important for the development of mariology to explain the veneration of Mary through their decisions not only in the area of Marian beliefs (Mariology) but also Marian practices and devotions. Before the 19th century, Popes promulgated Marian veneration by authorizing new Marian feast days, prayers, initiatives, the acceptance and support of Marian congregations.[216][217] Since the 19th century, Popes begin to use encyclicals more frequently. Thus Leo XIII, the Rosary Pope issued eleven Marian encyclicals. Recent Popes promulgated the veneration of the Blessed Virgin with two dogmas, Pius IX the Immaculate Conception in 1854 and the Assumption of Mary in 1950 by Pope Pius XII. Pius XII also promulgated the new feast Queenship of Mary celebrating Mary as Queen of Heaven and he introduced the first ever Marian year in 1954, a second one was proclaimed by John Paul II. Pius IX, Pius XI and Pius XII facilitated the veneration of Marian apparitions such as in Lourdes and Fátima. Later Popes such from John XXIII to Benedict XVI promoted the visit to Marian shrines (Benedict XVI in 2007 and 2008). The Second Vatican Council highlighted the importance of Marian veneration in Lumen gentium. During the Council, Paul VI proclaimed Mary to be the Mother of the Church.

Anti-clericalism

The 20th century saw the rise of various politically radical and anti-clerical governments. The 1926 Calles Law separating church and state in Mexico led to the Cristero War[218] in which over 3,000 priests were exiled or assassinated,[219] churches desecrated, services mocked, nuns raped and captured priests shot.[218] In the Soviet Union following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, persecution of the Church and Catholics continued well into the 1930s.[220] In addition to the execution and exiling of clerics, monks and laymen, the confiscation of religious implements and closure of churches was common.[221] During the 1936–39 Spanish Civil War, the Catholic hierarchy supported Francisco Franco's rebel Nationalist forces against the Popular Front government,[222] citing Republican violence directed against the Church.[223] The Church had been an active element in the polarising politics of the years preceding the Civil War.[224] Pope Pius XI referred to these three countries as a "terrible triangle" and the failure to protest in Europe and the United States as a "conspiracy of silence".

Italy

Pope Pius XI aimed to end the long breach between the papacy and the Italian government and to gain recognition once more of the sovereign independence of the Holy See. Most of the Papal States had been seized by the armies of King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy (1861–1878) in 1860 seeking Italian unification. Rome itself was seized by force in 1870 and the pope became the "prisoner in the Vatican." The Italian government's policies had always been anti-clerical until the First World War, when some compromises were reached.[225]

To bolster his own dictatorial Fascist regime, Benito Mussolini was also eager for an agreement. Agreement was reached in 1929 with the Lateran Treaties, which helped both sides.[226] According to the terms of the first treaty, Vatican City was given sovereignty as an independent nation in return for the Vatican relinquishing its claim to the former territories of the Papal States. Pius XI thus became a head of a tiny state with its own territory, army, radio station, and diplomatic representation. The Concordat of 1929 made Catholicism the sole religion of Italy (although other religions were tolerated), paid salaries to priests and bishops, recognized church marriages (previously couples had to have a civil ceremony), and brought religious instruction into the public schools. In turn the bishops swore allegiance to the Italian state, which had a veto power over their selection.[227] The Church was not officially obligated to support the Fascist regime; the strong differences remained but the seething hostility ended. The Church especially endorsed foreign policies such as support for the anti-Communist side in the Spanish Civil War, and support for the conquest of Ethiopia. Friction continued over the Catholic Action youth network, which Mussolini wanted to merge into his Fascist youth group. A compromise was reached with only the Fascists allowed to sponsor sports teams.[228]

Italy paid the Vatican 1750 million lira (about $100 million) for the seizures of church property since 1860. Pius XI invested the money in the stock markets and real estate. To manage these investments, the Pope appointed the lay-person Bernardino Nogara, who through shrewd investing in stocks, gold, and futures markets, significantly increased the Catholic Church's financial holdings. The income largely paid for the upkeep of the expensive-to-maintain stock of historic buildings in the Vatican which previously had been maintained through funds raised from the Papal States up until 1870.

The Vatican's relationship with Mussolini's government deteriorated drastically after 1930 as Mussolini's totalitarian ambitions began to impinge more and more on the autonomy of the Church. For example, the Fascists tried to absorb the Church's youth groups. In response Pius XI issued the encyclical Non abbiamo bisogno ("We Have No Need)") in 1931. It denounced the regime's persecution of the church in Italy and condemned "pagan worship of the State."[229]

Austria and Nazi Germany

The Vatican supported the Christian Socialists in Austria, a country with a majority Catholic population but a powerful secular element. Pope Pius XI favored the regime of Engelbert Dollfuss (1932–34), who wanted to remold society based on papal encyclicals. Dollfuss suppressed the anti-clerical elements and the socialists, but was assassinated by the Austrian Nazis in 1934. His successor Kurt von Schuschnigg (1934–38) was also pro-Catholic and received Vatican support. Germany annexed Austria in 1938 and imposed its own policies.[230]

Pius XI was prepared to negotiate concordats with any country that was willing to do so, thinking that written treaties were the best way to protect the Church's rights against governments increasingly inclined to interfere in such matters. Twelve concordats were signed during his reign with various types of governments, including some German state governments. When Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933 and asked for a concordat, Pius XI accepted. The Concordat of 1933 included guarantees of liberty for the Church in Nazi Germany, independence for Catholic organisations and youth groups, and religious teaching in schools.[231]

Nazi ideology was spearheaded by Heinrich Himmler and the SS. In the struggle for total control over German minds and bodies, the SS developed an anti-religious agenda.[232] No Catholic or Protestant chaplains were allowed in its units (although they were allowed in the regular army). Himmler established a special unit to identify and eliminate Catholic influences. The SS decided the German Catholic Church was a serious threat to its hegemony and while it was too strong to be abolished it was partly stripped of its influence, for example by closing its youth clubs and publications.[233]

After repeated violations of the Concordat, Pope Pius XI issued the 1937 encyclical Mit brennender Sorge which publicly condemned the Nazis' persecution of the Church and their ideology of neopaganism and racial superiority.[234]

World War II

After the Second World War began in September 1939, the Church condemned the invasion of Poland and subsequent 1940 Nazi invasions.[235] In the Holocaust, Pope Pius XII directed the Church hierarchy to help protect Jews and Gypsies from the Nazis.[236] While Pius XII has been credited with helping to save hundreds of thousands of Jews,[237] the Church has also been accused of antisemitism.[238] Albert Einstein, addressing the Catholic Church's role during the Holocaust, said the following: "Being a lover of freedom, when the revolution came in Germany, I looked to the universities to defend it, knowing that they had always boasted of their devotion to the cause of truth; but, no, the universities immediately were silenced. Then I looked to the great editors of the newspapers whose flaming editorials in days gone by had proclaimed their love of freedom; but they, like the universities, were silenced in a few short weeks... Only the Church stood squarely across the path of Hitler's campaign for suppressing truth. I never had any special interest in the Church before, but now I feel a great affection and admiration because the Church alone has had the courage and persistence to stand for intellectual truth and moral freedom. I am forced thus to confess that what I once despised I now praise unreservedly."[239] Other commentators have accused Pius of not doing enough to stop Nazi atrocities.[240] Debate over the validity of these criticisms continues to this day.[237]

Post-Industrial age

Second Vatican Council

The Catholic Church engaged in a comprehensive process of reform following the Second Vatican Council (1962–65).[241] Intended as a continuation of Vatican I, under Pope John XXIII the council developed into an engine of modernisation.[241][242] It was tasked with making the historical teachings of the Church clear to a modern world, and made pronouncements on topics including the nature of the church, the mission of the laity and religious freedom.[241] The council approved a revision of the liturgy and permitted the Latin liturgical rites to use vernacular languages as well as Latin during mass and other sacraments.[243] Efforts by the Church to improve Christian unity became a priority.[244] In addition to finding common ground on certain issues with Protestant churches, the Catholic Church has discussed the possibility of unity with the Eastern Orthodox Church.[245] And in 1966, Archbishop Andreas Rohracher expressed regret about the 18th century expulsions of the Salzburg Protestants from the Archbishopric of Salzburg.

Reforms

Changes to old rites and ceremonies following Vatican II produced a variety of responses. Some stopped going to church, while others tried to preserve the old liturgy with the help of sympathetic priests.[246] These formed the basis of today's Traditionalist Catholic groups, which believe that the reforms of Vatican II have gone too far. Liberal Catholics form another dissenting group who feel that the Vatican II reforms did not go far enough. The liberal views of theologians such as Hans Küng and Charles Curran, led to Church withdrawal of their authorization to teach as Catholics.[247] According to Professor Thomas Bokenkotter, most Catholics "accepted the changes more or less gracefully."[246] In 2007, Benedict XVI eased permission for the optional old Mass to be celebrated upon request by the faithful.[248]

A new Codex Iuris Canonici, called for by John XXIII, was promulgated by Pope John Paul II on 25 January 1983. This new Code of Canon Law includes numerous reforms and alterations in Church law and Church discipline for the Latin Church. It replaced the 1917 Code of Canon Law issued by Benedict XV.

Modernism

Liberation theology

In the 1960s, growing social awareness and politicization in the Latin American Church gave birth to liberation theology. The Peruvian priest, Gustavo Gutiérrez, became its primary proponent[249] and, in 1979, the bishops' conference in Mexico officially declared the Latin American Church's "preferential option for the poor".[250] Archbishop Óscar Romero, a supporter of aspects of the movement, became the region's most famous contemporary martyr in 1980, when he was murdered while celebrating Mass by forces allied with the government.[251] Both Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI (as Cardinal Ratzinger) denounced the movement.[252] The Brazilian theologian Leonardo Boff was twice ordered to cease publishing and teaching.[253] While Pope John Paul II was criticized for his severity in dealing with proponents of the movement, he maintained that the Church, in its efforts to champion the poor, should not do so by resorting to violence or partisan politics.[249] The movement is still alive in Latin America today, though the Church now faces the challenge of Pentecostal revival in much of the region.[254]

Sexuality and gender issues

The sexual revolution of the 1960s brought challenging issues for the Church. Pope Paul VI's 1968 encyclical Humanae Vitae reaffirmed the Catholic Church's traditional view of marriage and marital relations and asserted a continued proscription of artificial birth control. In addition, the encyclical reaffirmed the sanctity of life from conception to natural death and asserted a continued condemnation of both abortion and euthanasia as grave sins which were equivalent to murder.[255][256]

The efforts to lead the Church to consider the ordination of women led Pope John Paul II to issue two documents to explain Church teaching. Mulieris Dignitatem was issued in 1988 to clarify women's equally important and complementary role in the work of the Church.[257][258] Then in 1994, Ordinatio Sacerdotalis explained that the Church extends ordination only to men in order to follow the example of Jesus, who chose only men for this specific duty.[259][260][261]

Catholicism today

Catholic-Eastern Orthodox dialogue

In June 2004, the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I's visited Rome on the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul (29 June) for another personal meeting with Pope John Paul II, for conversations with the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity and for taking part in the celebration for the feast day in St. Peter's Basilica.

The Patriarch's partial participation in the Eucharistic liturgy at which the Pope presided followed the program of the past visits of Patriarch Dimitrios (1987) and Patriarch Bartholomew I himself: full participation in the Liturgy of the Word, joint proclamation by the Pope and by the Patriarch of the profession of faith according to the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed in Greek and as the conclusion, the final Blessing imparted by both the Pope and the Patriarch at the Altar of the Confessio.[262] The Patriarch did not fully participate in the Liturgy of the Eucharist involving the consecration and distribution of the Eucharist itself.[263][264]

In accordance with the Catholic Church's practice of including the Filioque clause when reciting the Creed in Latin,[265] but not when reciting the Creed in Greek,[266] Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI have recited the Nicene Creed jointly with Patriarchs Demetrius I and Bartholomew I in Greek without the Filioque clause.[267][268] The action of these Patriarchs in reciting the Creed together with the Popes has been strongly criticized by some elements of Eastern Orthodoxy, such as the Metropolitan of Kalavryta, Greece, in November 2008[269]

The declaration of Ravenna in 2007 re-asserted these beliefs, and re-stated the notion that the bishop of Rome is indeed the protos, although future discussions are to be held on the concrete ecclesiological exercise of papal primacy.

Sex abuse cases

Major lawsuits emerged in 2001 claiming that priests had sexually abused minors.[270] In response to the ensuing scandal, the Church has established formal procedures to prevent abuse, encourage reporting of any abuse that occurs and to handle such reports promptly, although groups representing victims have disputed their effectiveness.[271]

Some priests resigned, others were defrocked and jailed,[272] and there were financial settlements with many victims.[270] The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops commissioned a comprehensive study that found that four percent of all priests who served in the US from 1950 to 2002 had faced some sort of accusation of sexual misconduct.

Benedict XVI

With the election of Pope Benedict XVI in 2005, the Church largely saw a continuation of the policies of his predecessor, Pope John Paul II, with some notable exceptions: Benedict decentralized beatifications and reverted the decision of his predecessor regarding papal elections.[273] In 2007, he set a Church record by approving the beatification of 498 Spanish Martyrs. His first encyclical Deus caritas est discussed love and sex in continued opposition to several other views on sexuality.

Francis

With the election of Pope Francis in 2013, following the resignation of Benedict XVI, Francis is the current and first Jesuit pope, the first pope from the Americas, and the first from the Southern Hemisphere.[274] Since his election to the papacy, he has displayed a simpler and less formal approach to the office, choosing to reside in the Vatican guesthouse rather than the papal residence.[275] He has signalled numerous dramatic changes in policy as well—for example removing conservatives from high Vatican positions, calling on bishops to lead a simpler life, and taking a more pastoral attitude towards homosexuality.[276][277]

See also

- Anti-Catholicism

- Catholic-Protestant relations

- Criticism of the historical Catholic Church

- Great Church

- History of Christianity

- History of the Papacy

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- History of Western civilization

- Political Catholicism

- Role of the Catholic Church in civilization

- Vatican Splendors

- Timeline of the Catholic Church

- Legal history of the Catholic Church

Notes

- Joyce, George (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Regarding Peter as the first Bishop of Rome, "It is not, however, difficult to show that the fact of his [Peter's] bishopric is so well attested as to be historically certain. In considering this point, it will be well to begin with the third century, when references to it become frequent, and work backwards from this point. In the middle of the third century St. Cyprian expressly terms the Roman See the Chair of St. Peter, saying that Cornelius has succeeded to "the place of Fabian which is the place of Peter" (Ep 55:8; cf. 59:14). Firmilian of Caesarea notices that Stephen claimed to decide the controversy regarding rebaptism on the ground that he held the succession from Peter (Cyprian, Ep. 75:17). He does not deny the claim: yet certainly, had he been able, he would have done so. Thus in 250 the Roman episcopate of Peter was admitted by those best able to know the truth, not merely at Rome but in the churches of Africa and of Asia Minor. In the first quarter of the century (about 220) Tertullian (De Pud. 21) mentions Callistus's claim that Peter's power to forgive sins had descended in a special manner to him. Had the Roman Church been merely founded by Peter and not reckoned him as its first bishop, there could have been no ground for such a contention. Tertullian, like Firmilian, had every motive to deny the claim. Moreover, he had himself resided at Rome, and would have been well aware if the idea of a Roman episcopate of Peter had been, as is contended by its opponents, a novelty dating from the first years of the third century, supplanting the older tradition according to which Peter and Paul were co-founders, and Linus first bishop. About the same period, Hippolytus (for Lightfoot is surely right in holding him to be the author of the first part of the "Liberian Catalogue" — "Clement of Rome", 1:259) reckons Peter in the list of Roman bishops...."[15] - According to several historians, including Bart D. Ehrman, "Peter, in short, could not have been the first bishop of Rome, because the Roman church did not have anyone as its bishop until about a hundred years after Peter's death."[18]

- As examples, Bokenkotter cites that Sunday became a state day of rest, that harsher punishments were given for prostitution and adultery, and that some protections were given to slaves. (Bokenkotter, pp. 41–42.)

References

- "Vatican congregation reaffirms truth, oneness of Catholic Church". Catholic News Service. Archived from the original on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 862.

- Hitchcock, Geography of Religion (2004), p. 281, quote: "Some (Christian communities) had been evangelized by Peter, the disciple Jesus designated as the founder of his church. Once the position was institutionalized, historians looked back and recognized Peter as the first pope of the Christian church in Rome"

- Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), pp. 11, 14, quote: "The Church was founded by Jesus himself in his earthly lifetime.", "The apostolate was established in Rome, the world's capital when the church was inaugurated; it was there that the universality of the Christian teaching most obviously took its central directive–it was the bishops of Rome who very early on began to receive requests for adjudication on disputed points from other bishops."

- Chadwick, Henry, p. 37.

- Duffy, p. 18.; "By the beginning of the third century the church at Rome was an acknowledged point of reference for Christians throughout the Mediterranean world, and might even function as a court of appeal."

- Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), p. 81

- "Roman Catholicism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018. "The Roman Catholic Church traces its history to Jesus Christ and the Apostles."

- Kreeft, p. 980.

- Bokenkotter, p. 30.

- Barry, p. 46.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 880–881.

- Christian Bible, Matthew 16:13–20

- "Saint Peter the Apostle: Incidents important in interpretations of Peter". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- Joyce, George (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Was Peter in Rome?". Catholic Answers. 10 August 2004. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

if Peter never made it to the capital, he still could have been the first pope, since one of his successors could have been the first holder of that office to settle in Rome. After all, if the papacy exists, it was established by Christ during his lifetime, long before Peter is said to have reached Rome. There must have been a period of some years in which the papacy did not yet have its connection to Rome.

- Raymond E. Brown, 101 Questions and Answers on the Bible (Paulist Press 2003 ISBN 978-0-80914251-4), pp. 132–134

- Bart D. Ehrman. "Peter, Paul, and Mary Magdalene: The Followers of Jesus in History and Legend." Oxford University Press, USA. 2006. ISBN 0-19-530013-0. p. 84

- Oscar Cullmann (1962), Peter: Disciple, Apostle, Martyr (2 ed.), Westminster Press p. 234

- Henry Chadwick (1993), The Early Church, Penguin Books p. 18

- Bokenkotter, p. 24.

- Chadwick, Henry, pp. 23–24.

- Hitchcock, Geography of Religion (2004), p. 281, quote: "By the year 100, more than 40 Christian communities existed in cities around the Mediterranean, including two in North Africa, at Alexandria and Cyrene, and several in Italy."

- A.E. Medlycott, India and The Apostle Thomas, pp.1–71, 213–97; M.R. James, Apocryphal New Testament, pp.364–436; Eusebius, History, chapter 4:30; J.N. Farquhar, The Apostle Thomas in North India, chapter 4:30; V.A. Smith, Early History of India, p.235; L.W. Brown, The Indian Christians of St. Thomas, pp.49–59

- stthoma.com, stthoma.com, archived from the original on 8 February 2011, retrieved 8 August 2013

- McMullen, pp. 37, 83.

- Davidson, The Birth of the Church (2005), p. 115

- MacCulloch, Christianity, p. 109.

- Davidson, The Birth of the Church (2005), p. 146

- Davidson, The Birth of the Church (2005), p. 149

- MacCulloch, Christianity, pp.127–131.

- Duffy, pp. 9–10.

- Markus, p. 75.

- MacCulloch, Christianity, p. 134.

- MacCulloch, Christianity, p. 141.

- Davidson, The Birth of the Church (2005), pp. 169, 181

- Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), pp. 27–8, quote: "A distinguished succession of theological apologists added intellectual authority to the resources at the disposal of the papacy, at just that point in its early development when the absence of a centralized teaching office could have fractured the universal witness to a single body of ideas. At the end of the first century there was St. Clement of Rome, third successor to St. Peter in the see; in the second century there was St. Ignatius of Antioch, St. Irenaeus of Lyons and St. Justin Martyr; in the fourth century St. Augustine of Hippo.

- MacCulloch, Christianity, pp. 155–159, 164.

- Chadwick, Henry, p. 41.

- Chadwick, Henry, pp. 41–42, 55.