Catholicity

Catholicity (from Ancient Greek: καθολικός, romanized: katholikós, lit. 'general', 'universal', via Latin: catholicus)[1] is a concept pertaining to beliefs and practices widely accepted across numerous Christian denominations, most notably those that describe themselves as catholic in accordance with the Four Marks of the Church, as expressed in the Nicene Creed of the First Council of Constantinople in 381: "[I believe] in one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church."

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

The Catholic Church is also known as the Roman Catholic Church; the term Roman Catholic is used especially in ecumenical contexts and in countries where other churches use the term catholic, to distinguish it from broader meanings of the term.[2][3] Though the community led by the pope in Rome is known as the Catholic Church, the traits of catholicity, and thus the term catholic, are also ascribed to denominations such as the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Church, the Assyrian Church of the East. It also occurs in Lutheranism, Anglicanism, as well as Independent Catholicism and other Christian denominations. While traits used to define catholicity, as well as recognition of these traits in other denominations, vary among these groups, such attributes include formal sacraments, an episcopal polity, apostolic succession, highly structured liturgical worship, and other shared Ecclesiology.

Among Protestant and related traditions, catholic is used in the sense of indicating a self-understanding of the universality of the confession and continuity of faith and practice from Early Christianity, encompassing the "whole company of God's redeemed people".[4] Specifically among Methodist,[5] Lutheran,[6] Moravian,[7] and Reformed denominations[8] the term "catholic" is used in claiming to be "heirs of the apostolic faith".[9] These denominations consider themselves to be part of the catholic (universal) church, teaching that the term "designates the historic, orthodox mainstream of Christianity whose doctrine was defined by the ecumenical councils and creeds" and as such, most Reformers "appealed to this catholic tradition and believed they were in continuity with it." As such, the universality, or catholicity, of the church pertains to the entire body (or assembly) of believers united to Christ.[6]

History

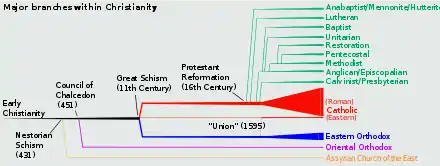

Summary of major divisions

A common belief related to catholicity is institutional continuity with the early Christian church founded by Jesus Christ. Many churches or communions of churches identify singularly or collectively as the authentic church. The following summarizes the major schisms and conflicts within Christianity, particularly within groups that identify as catholic; there are several competing historical interpretations as to which groups entered into schism with the original early church.

According to the theory of Pentarchy, the early undivided church came to be organized under the three patriarchs of Rome, Alexandria and Antioch, to which later were added the patriarchs of Constantinople and Jerusalem. The Bishop of Rome was at that time recognized as first among them, as is stated, for instance, in canon 3 of the First Council of Constantinople (381)—many interpret "first" as meaning here first among equals—and doctrinal or procedural disputes were often referred to Rome, as when, on appeal by Athanasius against the decision of the Council of Tyre (335), Pope Julius I, who spoke of such appeals as customary, annulled the action of that council and restored Athanasius and Marcellus of Ancyra to their sees.[10] The Bishop of Rome was also considered to have the right to convene ecumenical councils. When the Imperial capital moved to Constantinople, Rome's influence was sometimes challenged. Nonetheless, Rome claimed special authority because of its connection to the Apostles Peter[11][12] and Paul, who, many believe, were martyred and buried in Rome, and because the Bishop of Rome saw himself as the successor of Peter. There are sources that suggest that Peter was not the first Pope and never went to Rome.[13]

The 431 Council of Ephesus, the third ecumenical council, was chiefly concerned with Nestorianism, which emphasized the distinction between the humanity and divinity of Jesus and taught that, in giving birth to Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary could not be spoken of as giving birth to God. This Council rejected Nestorianism and affirmed that, as humanity and divinity are inseparable in the one person of Jesus Christ, his mother, the Virgin Mary, is thus Theotokos, God-bearer, Mother of God. The first great rupture in the Early Church followed this Council. Those who refused to accept the Council's ruling were largely Persian and are represented today by the Assyrian Church of the East and related churches, which, however, do not now hold a "Nestorian" theology. They are often called Ancient Oriental Churches.

The next major break was after the Council of Chalcedon (451). This Council repudiated Eutychian Monophysitism which stated that the divine nature completely subsumed the human nature in Christ. This Council declared that Christ, though one person, exhibited two natures "without confusion, without change, without division, without separation" and thus is both fully God and fully human. The Alexandrian Church rejected the terms adopted by this Council, and the Christian churches that follow the tradition of non-acceptance of the Council—they are not Monophysite in doctrine—are referred to as Pre-Chalcedonian or Oriental Orthodox Churches.

The next great rift within Christianity was in the 11th century. Longstanding doctrinal disputes, as well as conflicts between methods of church government, and the evolution of separate rites and practices, precipitated a split in 1054 that divided the church, this time between a "West" and an "East". Spain, England, France, the Holy Roman Empire, Poland, Bohemia, Slovakia, Scandinavia, the Baltic states, and Western Europe in general were in the Western camp, and Greece, Romania, Russia and many other Slavic lands, Anatolia, and the Christians in Syria and Egypt who accepted the Council of Chalcedon made up the Eastern camp. This division between the Western Church and the Eastern Church is called the East–West Schism.

In 1438, the Council of Florence convened, which featured a strong dialogue focussed on understanding the theological differences between the East and West, with the hope of reuniting the Catholic and Orthodox churches.[14] Several eastern churches reunited, constituting some of the Eastern Catholic Churches.

Another major division in the church occurred in the 16th century with the Protestant Reformation, after which many parts of the Western Church rejected Papal authority, and some of the teachings of the Western Church at that time, and became known as "Reformed" or "Protestant".

A much less extensive rupture occurred when, after the Roman Catholic Church's First Vatican Council, in which it officially proclaimed the dogma of papal infallibility, small clusters of Catholics in the Netherlands and in German-speaking countries formed the Old-Catholic (Altkatholische) Church.

Beliefs and practices

Use of the terms "catholicity" and "catholicism" depends on context. For times preceding the Great Schism, it refers to the Nicene Creed and especially to tenets of Christology, i.e. the rejection of Arianism. For times after the Great Schism, Catholicism (with the capital C) in the sense of the Catholic Church, combines the Latin Church, the Eastern Catholic Churches of Greek tradition, and the other Eastern Catholic Churches. Liturgical and canonical practices vary between all these particular Churches constituting the Roman and Eastern Catholic Churches (or, as Richard McBrien calls them, the "Communion of Catholic Churches").[15] Contrast this with the term Catholicos (but not Catholicism) in reference to the head of a Particular Church in Eastern Christianity. In the Roman Catholic Church, the term "catholic" is understood as to cover those who are baptized and in communion with the Pope.

Other Christians use it in an intermediate sense, neither just those Christians in communion with Rome, but more narrow than all Christians who recite the Creeds. They use it to distinguish their position from a Calvinistic or Puritan form of Protestantism. It is then meaningful to attempt to draw up a list of common characteristic beliefs and practices of this definition of catholicity:

- Direct and continuous organizational descent from the Church founded by Jesus and guided by the Holy Spirit.

- Belief that Jesus Christ is Divine, a doctrine officially clarified in the First Council of Nicaea and expressed in the Nicene Creed.

- Belief in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the belief that Christ is made manifest in the elements of Holy Communion.[16][17]

- Belief in the Apostolic succession of ordained ministry.

- Belief in the Catholic (from the Greek καθολικός, meaning "universal") Church as the Body of Christ, where Jesus is the head.

- Belief in the necessity and efficacy of sacraments.

- Liturgical and personal use of the Sign of the Cross.[18]

- The use of sacred images, candles, vestments and music, and often incense and water, in worship.

- Observation of the Christian liturgical year.[19]

- Devotion to the saints, particularly Mary, the mother of Jesus, as the human mother of Jesus Christ, or Theotokos ("God-bearer" or "Mother of God"), a title that became "Catholic" only after the Nicene Council, with the Council of Ephesus in 431, but a rejection of her worship.[20]

- Belief in the Communion of Saints.

Sacraments or sacred mysteries

Churches in the Roman Catholic tradition administer seven sacraments or "sacred mysteries": Baptism, Confirmation or Chrismation, Eucharist, Penance, also known as Reconciliation, Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders, and Matrimony. For Protestant Christians, only Baptism and Eucharist are considered sacraments.

In churches that consider themselves catholic, a sacrament is considered to be an efficacious visible sign of God's invisible grace. While the word mystery is used not only of these rites, but also with other meanings with reference to revelations of and about God and to God's mystical interaction with creation, the word sacrament (Latin: a solemn pledge), the usual term in the West, refers specifically to these rites.

- Baptism – the first sacrament of Christian initiation, the basis for all the other sacraments. Churches in the Catholic tradition consider baptism conferred in most Christian denominations "in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit" (cf. Matthew 28:19) to be valid, since the effect is produced through the sacrament, independently of the faith of the minister, though not of the minister's intention. This is not necessarily the case in other churches. As stated in the Nicene Creed, Baptism is "for the forgiveness of sins", not only personal sins, but also of original sin, which it remits even in infants who have committed no actual sins. Expressed positively, forgiveness of sins means bestowal of the sanctifying grace by which the baptized person shares the life of God. The initiate "puts on Christ" (Galatians 3:27), and is "buried with him in baptism ... also raised with him through faith in the working of God" (Colossians 2:12).

- Confirmation or Chrismation – the second sacrament of Christian initiation, the means by which the gift of the Holy Spirit conferred in baptism is "strengthened and deepened" (see, for example, Catechism of the Catholic Church, §1303) by a sealing. In the Western tradition it is usually a separate rite from baptism, bestowed, following a period of education called catechesis, on those who have at least reached the age of discretion (about 7)[21] and sometimes postponed until an age when the person is considered capable of making a mature independent profession of faith. It is considered to be of a nature distinct from the anointing with chrism (also called myrrh) that is usually part of the rite of baptism and that is not seen as a separate sacrament. In the Eastern tradition it is usually conferred in conjunction with baptism, as its completion, but is sometimes administered separately to converts or those who return to Orthodoxy. Some theologies consider this to be the outward sign of the inner "Baptism of the Holy Spirit", the special gifts (or charismata) of which may remain latent or become manifest over time according to God's will. Its "originating" minister is a validly consecrated bishop; if a priest (a "presbyter") confers the sacrament (as is permitted in some Catholic churches) the link with the higher order is indicated by the use of chrism blessed by a bishop. (In an Eastern Orthodox Church, this is customarily, although not necessarily, done by the primate of the local autocephalous church.)

- Eucharist – the sacrament (the third of Christian initiation) by which the faithful receive their ultimate "daily bread", or "bread for the journey", by partaking of and in the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ and being participants in Christ's one eternal sacrifice. The bread and wine used in the rite are, according to Catholic faith, in the mystical action of the Holy Spirit, transformed to be Christ's Body and Blood—his Real Presence. This transformation is interpreted by some as transubstantiation or metousiosis, by others as consubstantiation or sacramental union.

- Penance (also called Confession and Reconciliation) – the first of the two sacraments of healing. It is also called the sacrament of conversion, of forgiveness, and of absolution. It is the sacrament of spiritual healing of a baptized person from the distancing from God involved in actual sins committed. It involves the penitent's contrition for sin (without which the rite does not have its effect), confession (which in highly exceptional circumstances can take the form of a corporate general confession) to a minister who has the faculty to exercise the power to absolve the penitent,[22] and absolution by the minister. In some traditions (such as the Roman Catholic), the rite involves a fourth element – satisfaction – which is defined as signs of repentance imposed by the minister. In early Christian centuries, the fourth element was quite onerous and generally preceded absolution, but now it usually involves a simple task (in some traditions called a "penance") for the penitent to perform, to make some reparation and as a medicinal means of strengthening against further sinning.

- Anointing of the Sick (or Unction) – the second sacrament of healing. In it those who are suffering an illness are anointed by a priest with oil consecrated by a bishop specifically for that purpose. In past centuries, when such a restrictive interpretation was customary, the sacrament came to be known as "Extreme Unction", i.e. "Final Anointing", as it still is among traditionalist Catholics. It was then conferred only as one of the "Last Rites". The other "Last Rites" are Penance (if the dying person is physically unable to confess, at least absolution, conditional on the existence of contrition, is given), and the Eucharist, which, when administered to the dying, is known as "Viaticum", a word whose original meaning in Latin was "provision for a journey".

- Holy Orders – the sacrament which integrates someone into the Holy Orders of bishops, priests (presbyters), and deacons, the threefold order of "administrators of the mysteries of God" (1 Corinthians 4:1), giving the person the mission to teach, sanctify, and govern. Only a bishop may administer this sacrament, as only a bishop holds the fullness of the Apostolic Ministry. Ordination as a bishop makes one a member of the body that has succeeded to that of the Apostles. Ordination as a priest configures a person to Christ the Head of the Church and the one essential Priest, empowering that person, as the bishops' assistant and vicar, to preside at the celebration of divine worship, and in particular to confect the sacrament of the Eucharist, acting "in persona Christi" (in the person of Christ). Ordination as a deacon configures the person to Christ the Servant of All, placing the deacon at the service of the Church, especially in the fields of the ministry of the Word, service in divine worship, pastoral guidance and charity. Deacons may later be further ordained to the priesthood, but only if they do not have a wife. In some traditions (such as those of the Roman Catholic Church), while married men may be ordained, ordained men may not marry. In others (such as the Anglican-Catholic Church), clerical marriage is permitted.[note 1] Moreover, some sectors of Anglicanism "in isolation of the whole" have approved the ordination of openly active homosexuals to the priesthood and episcopacy, in spite of the support that Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, spoke for Anglican teaching on homosexuality, which he said the church "could not change simply because of a shift in society's attitude", noting also that those churches blessing same-sex unions and consecrating openingly gay bishops would not be able "to take part as a whole in ecumenical and interfaith dialogue." Thus in ecumenical matters, only if the Roman Catholic as well as Orthodox churches come to an understanding with first tier or primary bishops of the Anglican Communion can those churches (representing 95% of global Catholicism) implement an agreement with second tier or secondary Anglican bishops and their respective Anglican communities.[24][note 2][26][27]

- Holy Matrimony (or Marriage) – is the sacrament of joining a man and a woman (according to the churches' doctrines) for mutual help and love (the unitive purpose), consecrating them for their particular mission of building up the Church and the world, and providing grace for accomplishing that mission. Western tradition sees the sacrament as conferred by the canonically expressed mutual consent of the partners in marriage; Eastern and some recent Western theologians not in communion with the see of Rome view the blessing by a priest as constituting the sacramental action.

Denominational interpretations

Many individual Christians and Christian denominations consider themselves "catholic" on the basis, in particular, of apostolic succession. They may be described as falling into five groups:

- The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, which sees full communion with the Bishop of Rome as an essential element of Catholicism. Its constituent particular churches, Latin Church and the Eastern Catholic Churches, have distinct and separate jurisdictions, while still being "in union with Rome".[28]

- Those, like adherents of Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Church and the Church of the East, that claim unbroken apostolic succession from the early church and identify themselves as the Catholic Church.

- Those, such as the Old Catholic, Anglican and some Lutheran and other denominations, that claim unbroken apostolic succession from the early church and see themselves as a constituent part of the church.[note 3]

- Those who claim to be spiritual descendants of the Apostles but have no discernible institutional descent from the historic church and normally do not refer to themselves as catholic.

- Those who have acknowledged a break in apostolic succession, but have restored it in order to be in full communion with bodies that have maintained the practice. Examples in this category include the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada vis-à-vis their Anglican and Old Catholic counterparts.

For some confessions listed under category 3, the self-affirmation refers to the belief in the ultimate unity of the universal church under one God and one Savior, rather than in one visibly unified institution (as with category 1, above). In this usage, "catholic" is sometimes written with a lower-case "c". The Western Apostles' Creed and the Nicene Creed, stating "I believe in ... one holy catholic ... church", are recited in worship services. Among some denominations in category 3, "Christian" is substituted for "catholic" in order to denote the doctrine that the Christian Church is, at least ideally, undivided.[30][31][32]

Protestant churches each have their own distinctive theological and ecclesiological notions of catholicity.[33][34]

Catholic Church

In its Letter on Some Aspects of the Church Understood as Communion, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith stressed that the idea of the universal church as a communion of churches must not be presented as meaning that "every particular Church is a subject complete in itself, and that the universal church is the result of a reciprocal recognition on the part of the particular Churches". It insisted that "the universal Church cannot be conceived as the sum of the particular Churches, or as a federation of particular Churches".[35]

The Catholic Church considers only those in full communion with the Holy See in Rome as Catholics. While recognising the valid episcopates and Eucharist of the Eastern Orthodox Church in most cases, it does not consider Protestant denominations such as Lutheran ones to be genuine churches and so uses the term "ecclesial communities" to refer to them. Because the Catholic Church does not consider these denominations to have valid episcopal orders capable of celebrating a valid Eucharist, it does not classify them as churches "in the proper sense".[36][37][38]

The Catholic Church's doctrine of infallibility derives from the belief that the authority Jesus gave Peter as head of the church on earth has been passed on to his successors, the popes. Relevant Bible verses include [Matthew 16:18]; "And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven."

The Latin and Eastern Catholic Churches together form the "Catholic Church",[39] or "Roman Catholic Church",[40] the world's largest single religious body and the largest Christian denomination, as well as its largest Catholic church, comprising over half of all Christians (1.27 billion Christians of 2.1 billion) and nearly one-sixth of the world's population.[41][42][43][44] Richard McBrien would put the proportion even higher, extending it to those who are in communion with the Bishop of Rome only in "degrees".[45] It comprises 24 component "particular Churches" (also called "rites" in the Second Vatican Council's Decree on the Eastern Catholic Churches[46] and in the Code of Canon Law),[47] all of which acknowledge a primacy of jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome[48] and are in full communion with the Holy See and each other.

These particular churches or component parts are the Latin Church (which uses a number of different liturgical rites, of which the Roman Rite is by far prevalent) and the 23 Eastern Catholic Churches. Of the latter particular churches, 14 use the Byzantine Rite for their liturgy.[49] Within the universal Church, each "particular church", whether Eastern or Western, is of equal dignity.[50] Finally, in its official documents, the Catholic Church, though made up of several particular churches, "continues to refer to itself as the 'Catholic Church'"[51] or, less frequently but consistently, as the 'Roman Catholic Church', owing to its essential[40] link with the Bishop of Rome.[note 4]

Richard McBrien, in his book Catholicism, disagrees with the synonymous use of "Catholic" and "Roman Catholic":

But is 'Catholic' synonymous with 'Roman Catholic'? And is it accurate to refer to the Roman Catholic Church as simply the 'Roman Church'? The answer to both questions is no. The adjective 'Roman' applies more properly to the diocese, or see, of Rome than to the worldwide Communion of Catholic Churches that is in union with the Bishop of Rome. Indeed, it strikes some Catholics as contradictory to call the Church 'Catholic' and 'Roman' at one and the same time. Eastern-rite Catholics, of whom there are more than twenty million, also find the adjective 'Roman' objectionable. In addition to the Latin, or Roman, tradition, there are seven non-Latin, non-Roman ecclesial traditions: Armenian, Byzantine, Coptic, Ethiopian, East Syriac (Chaldean), West Syriac, and Maronite. Each to the Churches with these non-Latin traditions is as Catholic as the Roman Catholic Church. Thus, not all Catholics are Roman Catholic... [T]o be Catholic—whether Roman or non-Roman—in the ecclesiological sense is to be in full communion with the Bishop of Rome and as such to be an integral part of the Catholic Communion of Churches.[52]

McBrien says that, on an official level, what he calls the "Communion of Catholic Churches" always refers to itself as "The Catholic Church".[53] However, counter examples such as seen above of the term "Roman Catholic Church" being used by popes and departments of the Holy See exist. The Latin Archdiocese of Detroit, for example, lists eight Eastern Catholic churches, each with its own bishop, as having one or more parishes in what is also the territory of the Latin archdiocese, yet each is designated as being in "full communion with the Roman Church".[54]

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church maintains the position that it is their communion which actually constitutes the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church.[55][56] Eastern Orthodox Christians consider themselves the heirs of the first-millennium patriarchal structure that developed in the Eastern Church into the model of the pentarchy, recognized by Ecumenical Councils, a theory that "continues to hold sway in official Greek circles to the present day".[57]

Since the theological disputes that occurred from the 9th to 11th centuries, culminating in the final split of 1054, the Eastern Orthodox churches have regarded Rome as a schismatic see that has violated the essential catholicity of the Christian faith by introducing innovations of doctrine (see Filioque). On the other hand, the model of the pentarchy was never fully applied in the Western Church, which preferred the theory of the Primacy of the Bishop of Rome, favoring Ultramontanism over Conciliarism.[58][59][60][61] The title "Patriarch of the West" was rarely used by the popes until the 16th and 17th centuries, and was included in the Annuario Pontificio from 1863 to 2005, being dropped in the following year as never very clear, and having become over history "obsolete and practically unusable".[60][61]

Oriental Orthodoxy

The Oriental Orthodox churches (Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Ethiopian, Eritrean, Malankaran) also maintain the position that their communion constitutes the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church. In this sense, Oriental Orthodoxy upholds its own ancient ecclesiological traditions of apostolicity (apostolic continuity) and catholicity (universality) of the Church.[62]

Assyrian Church of the East

Similar notion of the catholicity was also maintained in the former Church of the East, with its distinctive theological and ecclesiological characteristics and traditions. That notion was inherited by both of its modern secessions: the Chaldean Catholic Church that is part of the Catholic Church, and the Assyrian Church of the East whose full official name is: The Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East,[63] along with its off-shot in turn the Ancient Church of the East whose full official name is: The Holy Apostolic Catholic Ancient Church of the East.[64] These churches are using the term catholic in their names in the sense of traditional catholicity. They are not in communion with the Catholic Church.

Lutheranism

The Augsburg Confession found within the Book of Concord, a compendium of belief of the Lutheran Churches, teaches that "the faith as confessed by Luther and his followers is nothing new, but the true catholic faith, and that their churches represent the true catholic or universal church".[65] When the Lutherans presented the Augsburg Confession to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor in 1530, they believe to have "showed that each article of faith and practice was true first of all to Holy Scripture, and then also to the teaching of the church fathers and the councils".[65]

Following the Reformation, Lutheran Churches, such as the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland and the Church of Sweden, retained apostolic succession, with former Roman Catholic bishops simply becoming Lutheran and continuing to occupy their chairs.[66][67][68] The 20th century movement of High Church Lutheranism championed Evangelical Catholicity, restoring, in some cases, apostolic succession, to Lutheran Churches in Germany where it was lacking.[69]

Anglicanism

Introductory works on Anglicanism, such as The Study of Anglicanism, typically refer to the character of the Anglican tradition as "Catholic and Reformed",[70] which is in keeping with the understanding of Anglicanism articulated in the Elizabethan Settlement of 1559 and in the works of the earliest standard Anglican divines such as Richard Hooker and Lancelot Andrewes. Yet different strains in Anglicanism, dating back to the English Reformation, have emphasized either the Reformed, Catholic, or "Reformed Catholic" nature of the tradition.

Anglican theology and ecclesiology has thus come to be typically expressed in three distinct, yet sometimes overlapping manifestations: Anglo-Catholicism (often called "high church"), Evangelical Anglicanism (often called "low church"), and Latitudinarianism ("broad church"), whose beliefs and practices fall somewhere between the two. Though all elements within the Anglican Communion recite the same creeds, Evangelical Anglicans generally regard the word catholic in the ideal sense given above. In contrast, Anglo-Catholics regard the communion as a component of the whole Catholic Church, in spiritual and historical union with the Roman Catholic, Old Catholic and several Eastern churches. Broad Church Anglicans tend to maintain a mediating view, or consider the matter one of adiaphora. These Anglicans, for example, have agreed in the Porvoo Agreement to interchangeable ministries and full eucharistic communion with Lutherans.[71][72]

The Catholic nature or strain of the Anglican tradition is expressed doctrinally, ecumenically (chiefly through organizations such as the Anglican—Roman Catholic International Commission), ecclesiologically (through its episcopal governance and maintenance of the historical episcopate), and in liturgy and piety. The 39 Articles hold that "there are two Sacraments ordained of Christ our Lord in the Gospel, that is to say, Baptism and the Supper of the Lord", and that "those five commonly called Sacraments, that is to say, Confirmation, Penance, Orders, Matrimony, and Extreme Unction, are not to be counted for Sacraments of the Gospel"; some Anglo-Catholics interpret this to mean that there are a total of Seven Sacraments.[73] Many Anglo-Catholics practice Marian devotion, recite the rosary and the angelus, practice eucharistic adoration, and seek the intercession of saints. In terms of liturgy, most Anglicans use candles on the altar or communion table and many churches use incense and bells at the Eucharist, which is amongst the most pronounced Anglo-Catholics referred to by the Latin-derived word "Mass" used in the first prayer book and in the American Prayer Book of 1979. In numerous churches the Eucharist is celebrated facing the altar (often with a tabernacle) by a priest assisted by a deacon and subdeacon. Anglicans believe in the Real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, though Anglo-Catholics interpret this to mean a corporeal presence, rather than a pneumatic presence. Different Eucharistic rites or orders contain different, if not necessarily contradictory, understandings of salvation. For this reason, no single strain or manifestation of Anglicanism can speak for the whole, even in ecumenical statements (as issued, for example, by the Anglican – Roman Catholic International Commission).[74][75][76]

The growth of Anglo-Catholicism is strongly associated with the Oxford Movement of the 19th century. Two of its leading lights, John Henry Newman and Henry Edward Manning, both priests, ended up joining the Roman Catholic Church, becoming cardinals. Others, like John Keble, Edward Bouverie Pusey, and Charles Gore became influential figures in Anglicanism. The previous Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, is a patron of Affirming Catholicism, a more liberal movement within Catholic Anglicanism. Conservative Catholic groups also exist within the tradition, such as Forward in Faith. There are about 80 million Anglicans in the Anglican Communion, comprising 3.6% of global Christianity.[77]

Methodism

The 1932 Deed of Union of the Methodist Church of Great Britain teaches that:[78]

The Methodist Church claims and cherishes its place in the Holy Catholic Church which is the Body of Christ. It rejoices in the inheritance of the Apostolic Faith and loyally accepts the fundamental principles of the historic creeds and of the Protestant Reformation. It ever remembers that in the providence of God Methodism was raised up to spread Scriptural Holiness through the land by the proclamation of the Evangelical Faith, and declares its unfaltering resolve to be true to its divinely appointed mission. The doctrines of the Evangelical Faith, which Methodism has held from the beginning and still holds, are based upon the divine revelation recorded in the Holy Scriptures. The Methodist Church acknowledges this revelation as the supreme rule of faith and practice. The Methodist Church recognises two sacraments, namely, Baptism and the Lord’s Supper, as of divine appointment and of perpetual obligation, of which it is the privilege and duty of members of the Methodist Church to avail themselves.[78]

The theologian Stanley Hauerwas wrote that Methodism "stands centrally in the Catholic tradition" and that "Methodists indeed are even more Catholic than the Anglicans who gave us birth, since Wesley, of blessed memory, held to the Eastern fathers in a more determinative way than did any of the Western churches—Protestant or Catholic."[79]

Reformed

Within Reformed Christianity the word "catholic" is generally taken in the sense of "universal" and in this sense many leading Protestant denominations identify themselves as part of the catholic church. The puritan Westminster Confession of Faith adopted in 1646 (which remains the Confession of the Church of Scotland) states for example that:

The catholic or universal Church, which is invisible, consists of the whole number of the elect, that have been, are, or shall be gathered into one, under Christ the Head thereof; and is the spouse, the body, the fulness of Him that fills all in all.[80]

The London Confession of the Reformed Baptists repeats this with the emendation "which (with respect to the internal work of the Spirit and truth of grace) may be called invisible".[81] The Church of Scotland's Articles Declaratory begin "The Church of Scotland is part of the Holy Catholic or Universal Church".

In Reformed Churches there is a Scoto-Catholic grouping within the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. Such groups point to their churches' continuing adherence to the "Catholic" doctrine of the early Church Councils. The Articles Declaratory of the Constitution of the Church of Scotland of 1921 defines that church legally as "part of the Holy Catholic or Universal Church".[70]

Independent Catholicism

The Old Catholics, the Liberal Catholic Church, the Augustana Catholic Church, the American National Catholic Church, the Apostolic Catholic Church (ACC), the Aglipayans (Philippine Independent Church), the African Orthodox Church, the Polish National Catholic Church of America, and many Independent Catholic churches, which emerged directly or indirectly from and have theology and practices largely similar to Latin Catholicism, regard themselves as "Catholic" without full communion with the Bishop of Rome, whose claimed status and authority they generally reject. The Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association, a division of the People's Republic of China's Religious Affairs Bureau exercising state supervision over mainland China's Catholics, holds a similar position, while attempting, as with Buddhism and Protestantism, to indoctrinate and mobilize for Communist Party objectives.[82]

Some Independent Catholics accept that, among bishops, that of Rome is primus inter pares, and hold that conciliarism is a necessary check against ultramontanism. They are however, by definition, not recognised by the Catholic Church.

Other views by individual scholars

Richard McBrien considers that the term "Catholicism" refers exclusively and specifically to that "Communion of Catholic Churches" in communion with the Bishop of Rome.[83] According to McBrien, Catholicism is distinguished from other forms of Christianity in its particular understanding and commitment to tradition, the sacraments, the mediation between God, communion, and the See of Rome.[84] According to Bishop Kallistos Ware, the Orthodox Church has these things as well, though the primacy of the See of Rome is only honorific, showing non-jurisdictional respect for the Bishop of Rome as the "first among equals" and "Patriarch of the West".[85] Catholicism, according to McBrien's paradigm, includes a monastic life, religious institutes, a religious appreciation of the arts, a communal understanding of sin and redemption, and missionary activity.[note 5]

Henry Mills Alden, in Harper's New Monthly Magazine, writes that:

The various Protestant sects can not constitute one church because they have no intercommunion...each Protestant Church, whether Methodist or Baptist or whatever, is in perfect communion with itself everywhere as the Roman Catholic; and in this respect, consequently, the Roman Catholic has no advantage or superiority, except in the point of numbers. As a further necessary consequence, it is plain that the Roman Church is no more Catholic in any sense than a Methodist or a Baptist.[87]

— Henry Mills Alden, Harper's New Monthly Magazine Volume 37, Issues 217–222

As such, according to this viewpoint, "for those who 'belong to the Church', the term Methodist Catholic, or Presbyterian Catholic, or Baptist Catholic, is as proper as the term Roman Catholic."[88] "It simply means that body of Christian believers over the world who agree in their religious views, and accept the same ecclesiastical forms."[88]

See also

- Anti-Catholicism

- De fide Catolica

- Ecclesiastical differences between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church

Notes

- In regard to the ordination of women to the episcopacy, one cannot underestimate the chasm that is currently developing between the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental and Roman Catholic churches, on the one hand, and the Lutheran, Anglican and Independent Catholic churches, on the other hand. Cardinal Walter Kasper, President of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, for example, noted this when he addressed some Anglican bishops in 2006. Quoting St Cyprian of Carthage (d. 258), he said the episcopate is one, which means that "each part of it is held by each one for the whole"; that bishops were instruments of unity not only within the contemporary Church, but also across time, within the universal Church. This being the case, he continued, "the decision for the ordination of women to the Episcopal office ... must not in any way involve a conflict between the majority and the minority." Such a decision should be made "with the consensus of the ancient Churches of the East and West." To do otherwise "would spell the end" to any kind of unity.[23]

- The Russian Orthodox Church, which because of the episcopal ordination of Gene Robinson severed its dialogue with the United States Episcopal Church, while declaring itself open to "contacts and cooperation with those American Episcopalians who remain faithful to the gospel's moral teaching", stated that it was willing to restore relations with those Episcopal dioceses that refused to recognize the election of Katharine Jefferts Schori as their Church's presiding bishop[25]

- Old Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran movements all have historical ties to the Catholic Church; however, the Catholic Church has judged the succession of Anglican and Lutheran ordinations to be invalid, while giving limited recognition to the validity of the sacraments of some branches of the Old Catholic movement.[29] For further information, see Catholic Church and ecumenism.

- For example, in his encyclical Humani Generis Archived 19 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 27–28 Pope Pius XII decried the error of those who denied that they were bound by "the doctrine, explained in Our Encyclical Letter of a few years ago, and based on the Sources of Revelation, which teaches that the Mystical Body of Christ and the Roman Catholic Church are one and the same thing"; and in his Divini Illius Magistri Archived 23 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Pope Pius XI wrote: "In the City of God, the Holy Roman Catholic Church, a good citizen and an upright man are absolutely one and the same thing." On other occasions too, both when signing agreements with other Churches (e.g. that with Patriarch Mar Ignatius Yacoub III of the Syriac Orthodox Church) and in giving talks to various groups (e.g. Benedict XVI in Warsaw), the Popes refer to the Church that they head as the Roman Catholic Church.

- In Richard McBrien's book, Catholicism, he notes (on page 19) that his book was "written in the midst of yet another major crisis in the history of the Roman Catholic Church...." Never once does he indicate in his book that Catholicism refers to churches not in communion with the See of Rome.[86]

References

- "catholic, adj. and n." Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 16 May 2020., "catholicity, n." Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- e.g. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Galloway diocesan website

- e.g. The Roman Catholic Church and the World Methodist Council, report from the Holy See website

- George, Timothy (18 September 2008). "What do Protestant churches mean when they recite "I believe in the holy catholic church" and "the communion of saints" in the Apostles' Creed?". Christianity Today. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

The Protestant reformers understood themselves to be a part of "the holy catholic church."Millions of Protestants still repeat these words every week as they stand in worship to recite the Apostles' Creed. The word catholic was first used in this sense in the early second century when Ignatius of Antioch declared, "Where Jesus Christ is, there is the catholic church." Jesus Christ is the head of the church, as well as its Lord. Protestant believers in the tradition of the Reformation understand the church to be the body of Christ extended throughout time as well as space, the whole company of God's redeemed people through the ages.

- Abraham, William J.; Kirby, James E. (24 September 2009). The Oxford Handbook of Methodist Studies. OUP Oxford. p. 401. ISBN 9780191607431.

Acknowledging the considerable agreement between Anglicans and Methodists concerning faith and doctrine, and believing there to be sufficient convergence in understanding ministry and mission, Sharing in the Apostolic Communion (Anglican-Methodist Dialogue 1996) invited the WMC and the Lambeth Conference to recognize and affirm that: Both Anglicans and Methodists belong to the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church of Jesus Christ and participate in the apostolic mission of the whole people of God; in the churches of our two communions the word of God is authentically preached and the sacraments instituted of Christ are duly administered; Our churches share in common confession and heritage of the apostolic faith' (§95).

- Gassmann, Günther (1999). Fortress Introduction to the Lutheran Confessions. Fortress Press. p. 204. ISBN 9781451418194.

Uncapitalized, it designates the historic, orthodox mainstream of Christianity whose doctrine was defined by the ecumenical councils and creeds. Most reformers, not just Lutherans, appealed to this catholic tradition and believed they were in continuity with it.

- "Studying Moravian Doctrine: Ground of the Unity, Part II". Moravian Church. 2005. Archived from the original on 25 July 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

The Moravian Church does not have a different understanding of God than other churches, but stresses what we have in common with all of the world's Christians. "Christendom" here simply means Christianity. We see here not only the influence of the ecumenical movement on the Ground of the Unity but also our historical perspective that we are part of the one holy catholic and apostolic church.

- McKim, Donald K. (1 January 2001). The Westminster Handbook to Reformed Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780664224301.

- Block, Matthew (24 June 2014). "Are Lutherans Catholic?". First Things. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

The universality of the Church is, through God's grace, a reality despite doctrinal disagreements; but it is not a license for the downplaying of these doctrinal differences. The Church catholic is also the Church apostolic—which is to say, it is the Church which "stands firm and holds to the traditions" which have been taught through the words of the Apostles (2 Thessalonians 2:15). And this teaching—which is truly the Word of God (2 Timothy 3:16, 2 Peter 1:19–21)—has been passed on to us today in its fullness through the Scriptures. To be catholic, then, is to be heirs of the apostolic faith. It is to be rooted firmly in the Apostle's teaching as recorded for us in Scripture, the unchanging Word of God. But while this Word is unchanging, it does not follow that it is static. The history of the Church in the world is the history of Christians meditating upon Scripture. We must look to this history as our own guide in understanding Scripture. To be sure, the Church's tradition of interpretation has erred from time to time—we find, for example, that the Fathers and Councils sometimes disagree with one another—but it is dangerous to discount those interpretations of Scripture which have been held unanimously from the very beginning of the Church.

- Catholic Encyclopedia, Pope St. Julius I

- Radeck, Francisco; Radecki, Dominic (2004). Tumultuous Times. St. Joseph's Media. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-9715061-0-7.

- "The Hierarchical Constitution of the Church - 880-881". The Vatican. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- "St Peter was not the first Pope and never went to Rome, claims Channel 4". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Geanakoplos, Deno John (1989). Constantinople and the West. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299118800.

- Mc Brien, The Church, 6.

- Murray, Paul (6 May 2010). Receptive Ecumenism and the Call to Catholic Learning: Exploring a Way for Contemporary Ecumenism. Oxford University Press. p. 839. ISBN 9780191615290.

With this, the 1982 Final Report already attests to a substantial agreement regarding eucharistic doctrine between the Anglican and Roman Catholic churches and there is little doubt that many Anglicans, Methodists, and Reformed Christians would affirm the reality of Christ's presence in the Eucharist in the same way as Roman Catholics do, though not using the same formula, in a manner that some Evangelicals and, as we must acknowledge, some Roman Catholics would not.

- Gros, Jeffrey; Mulhall, Daniel S. (18 September 2013). The Ecumenical Christian Dialogues and The Catechism of the Catholic Church. Paulist Press. p. 128. ISBN 9781616438098.

The Methodist churches, being heirs of the Anglican Church, have a heritage of faith in the real presence of Christ in the Lord's Supper and an understanding of the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist.

- Martin, Charles Alfred (1913). Catholic Religion: A Statement of Christian Teaching and History. B. Herder. p. 214.

Sign of the Cross. The cross is the standard of the Christian faith—the sign of salvation. As the government flies its flag over ship and port and public building, so the Church crowns her steeples, her altars, and the very tombs of her children, with the emblem of our hope. Catholic people sanctify their homes with the sacred symbol. When one sees the crucifix reverently hung on the walls of a room, he knows the place is not the home of an infidel. From the earliest centuries the Christians blessed themselves with the Sign of the Cross, as we learn from Tertullian, Jerome, Ambrose, Athanasius, and many other Fathers.

- Martin, Charles Alfred (1913). Catholic Religion: A Statement of Christian Teaching and History. B. Herder. p. 214.

Ecclesiastical Year. In the feasts of the ecclesiastical year, the Church makes the day and nights join with His other works to bless the Lord. The Church year is mainly the anniversary celebration of the great events in the life of Christ.

- Campbell, Ted (1 January 1996). Christian Confessions: A Historical Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780664256500.

The Lutheran Formula of Concord refers to Mary as the "Mother of God", and the most recently approved Book of Common Prayer of the Episcopal Church in the United States includes a translation of the Chalcedonian Definition of Faith, which refers to Mary as Theotokos, although its translation elects to render this by the less offensive "Mary the Virgin, the God-bearer (Theotokos)". Since Lutheran, Anglican, and Reformed confessions affirm the faith expressed at the Council of Chalcedon and condemn Nestorianism, it could be argued that there is widespread agreement between the Reformation traditions on the affirmation that Mary is Theotokos, "Mother of God"...

- "Code of Canon Law, canon 891". Intratext.com. 4 May 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- "Chapter II : The Minister of the Sacrament of Penance". IntraText. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- James Roberts, "Women bishops 'would spell the end of unity hopes'" in The Tablet, 10 June 2006, 34.

- "Rowan Williams predicts schism over homosexuality" (The Tablet 1 August 2009, 33).

- Letter of Metropolitan Kirill of Smolensk and Kaliningrad).

- Stan Chu Ilo, "An African view on ordaining Gene Robinson", The National Catholic Reporter, 12 December 2003, 26.

- Matthew Moore, "Archbishop of Canterbury foresees a 'two-tier' church to avoid gay schism", The Telegraph.co.uk, 27 July 2009.

- Richard McBrien, Catholicism (Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1981), 680.

- Father Edward McNamara, Legionary of Christ (14 February 2012). "The Old Catholic and Polish National Churches". Rome: Zenit. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- "Apostles' Creed". The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- "Nicene Creed". Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- "Texts of the Three Chief Symbols are taken from the Book of Concord, Tappert edition". The International Lutheran Fellowship. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- Braaten & Jenson 1996.

- Stewart 2015.

- "SOME ASPECTS OF THE CHURCH UNDERSTOOD AS COMMUNION".

- Fowler, Jeaneane D. (1997). World Religions. Sussex Academic Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-898723-48-6.

- "Declaration Dominus Iesus". Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. p. 17. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013.

The ecclesial communities which have not preserved the valid Episcopate and the genuine and integral substance of the Eucharistic mystery are not Churches in the proper sense; however, those who are baptized in these communities are, by Baptism, incorporated in Christ and thus are in a certain communion, albeit imperfect, with the Church.

- "[The expression sister Churches] has been applied improperly by some to the relationship between the Catholic Church on the one hand, and the Anglican Communion and non-catholic ecclesial communities on the other. ... it must also be borne in mind that the expression sister Churches in the proper sense, as attested by the common Tradition of East and West, may only be used for those ecclesial communities that have preserved a valid episcopate and Eucharist" (Note on the expression "sister Churches" issued by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on 30 June 2000).

- McBrien, The Church, 356. McBrien also says they form the "Communion of Catholic Churches", a name not used by the Church itself, which has pointed out the ambiguity of this term in a 1992 letter from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith "on some aspects of the Church understood as communion", 8.

- "The Catholic Church is also called the Roman Church to emphasize that the centre of unity, which is an essential for the Universal Church, is in the Roman See" (Thomas J. O'Brien, An Advanced Catechism of Catholic Faith and Practice, Kessinger Publishers, 2005 ISBN 1-4179-8447-3, p. 70.)

- "Number of Catholics growing throughout the world".

- http://cara.georgetown.edu/staff/webpages/Global%20Catholicism%20Release.pdf

- Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population: Main Page, Pew Research Center. There are 1.5 billion Muslims, nearly a billion of whom are Sunnite (nearly 90% of Muslim population), thus the latter forming the second largest single religious body.

- Todd Johnson, David Barrett, and Peter Crossing, "Christianity 2010: A View from the New Atlas of Global Christianity", International Bulletin of Missionary Research, Vol., 34, No.1, January 2010, pp. 29–36.

- Richard McBrien, The Church: The Evolution of Catholicism, 6. ISBN 978-0-06-124521-3 McBrien says this: Vatican II "council implicitly set aside the category of membership and replaced it with degrees." "...it is not a matter of either/or—either one is in communion with the Bishop of Rome, or one is not. As in a family, there are degrees of relationships: parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins, nephews, nieces, in-laws. In many cultures, the notion of family is broader than blood and legal relationships."

- Orientalium Ecclesiarum Archived 1 September 2000 at the Wayback Machine, 2

- "Code of Canon Law – IntraText".

- "Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, canon 43". Intratext.com. 4 May 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- Annuario Pontificio, 2012 edition, pages 1140–1141 (ISBN 978-88-209-8722-0).

- Orientalium Ecclesiarum, 3

- Thomas P. Rausch, S.J., Catholicism in the Third Millennium (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press), xii.

- Richard McBrien, The Church, 6.

- McBrien, The Church, 351–371

- "Archdiocese of Detroit listing of Eastern Churches". Aodonline.org. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Meyendorff 1966.

- Meyendorff 1983.

- The A to Z of the Orthodox Church, p. 259, by Michael Prokurat, Michael D. Peterson, Alexander Golitzin, published by Scarecrow Press in 2010 ()

- Milton V. Anastos (2001). Aspects of the Mind of Byzantium (Political Theory, Theology, and Ecclesiastical Relations with the See of Rome). Myriobiblos.gr. Ashgate Publications, Variorum Collected Studies Series. ISBN 0-86078-840-7. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- "L'idea di pentarchia nella cristianità". Homolaicus.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- "Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, press release on the suppression of the title "Patriarch of the West" in the 2006 Annuario Pontificio". Vatican.va. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- Catholic Online (22 March 2006). "Vatican explains why pope no longer "patriarch of the West"". Catholic.org. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- Krikorian 2010, pp. 45, 128, 181, 194, 206.

- "Official site of the Assyrian Church of the East". Assyrianchurch.org. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "Official pages of the Ancient Church of the East". Stzaiacathedral.org.au. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- Ludwig, Alan (12 September 2016). "Luther's Catholic Reformation". The Lutheran Witness. Concordia Publishing House.

When the Lutherans presented the Augsburg Confession before Emperor Charles V in 1530, they carefully showed that each article of faith and practice was true first of all to Holy Scripture, and then also to the teaching of the church fathers and the councils and even the canon law of the Church of Rome. They boldly claim, "This is about the Sum of our Doctrine, in which, as can be seen, there is nothing that varies from the Scriptures, or from the Church Catholic, or from the Church of Rome as known from its writers" (AC XXI Conclusion 1). The underlying thesis of the Augsburg Confession is that the faith as confessed by Luther and his followers is nothing new, but the true catholic faith, and that their churches represent the true catholic or universal church. In fact, it is actually the Church of Rome that has departed from the ancient faith and practice of the catholic church (see AC XXIII 13, XXVIII 72 and other places).

- Gassmann, Günther; Larson, Duane Howard; Oldenburg, Mark W. (2001). Historical Dictionary of Lutheranism. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810839458. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

In addition to the primary understanding of succession, the Lutheran confessions do express openness, however, to the continuation of the succession of bishops. This is a narrower understanding of apostolic succession, to be affirmed under the condition that the bishops support the Gospel and are ready to ordain evangelical preachers. This form of succession, for example, was continued by the Church of Sweden (which included Finland) at the time of the Reformation.

- Richardson, Alan; John, John Bowden (1 January 1983). The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0664227481. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

The churches of Sweden and Finland retained bishops and the conviction of being continuity with the apostolic succession, while in Denmark the title bishop was retained without the doctrine of apostolic succession.

- Benedetto, Robert; Duke, James O. (13 August 2008). The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History: The Early, Medieval, and Reformation Eras. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 594. ISBN 978-0664224165. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

In Sweden the apostolic succession was preserved because the Catholic bishops were allowed to stay in office, but they had to approve changes in the ceremonies.

- Drummond, Andrew Landale (13 March 2015). German Protestantism Since Luther. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 261. ISBN 9781498207553.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin; Geoffrey William Bromiley (2005). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. David B. Barrett. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 269, 494. ISBN 978-0-8028-2416-5.

- "Anglican-Lutheran agreement signed", The Christian Century, 13 November 1996, 1005.

- "Two Churches Now Share a Cleric", New York Times, 20 October 1996, 24.

- "How many Sacraments are there in Anglicanism?". Maple Anglican. 7 November 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- Rowan A. Greer, "Anglicanism as an ongoing argument", The Witness, May 1998, 23.

- Matt Cresswell, "Anglican conservatives say 'second reformation' is already under way", The Tablet, 28 June 2008, 32.

- Philip Jenkins, "Defender of the Faith", The Atlantic Monthly, November 2003, 46–9.

- David Barrett, "Christian World Communities: Five Overviews of Global Christianity, AD 1800–2025", in International Bulletin of Missionary Research, January 2009, Vol. 33, No 1, pp. 31.

- Statements and Reports of the Methodist Church on Faith and Order. Vol. 1. Trustees for Methodist Church Purposes. 2000. p. 21. ISBN 1-85852-183-1.

- Stanley Hauerwas (1990). "The Importance of Being Catholic: A Protestant View". First Things. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- The Westminster Confession of Faith (1646), Article XXV

- The London Confession (1689), Chapter 26

- Simon Scott Plummer, "China's Growing Faiths" in The Tablet, March 2007. Based on a review of Religious Experience in Contemporary China by Kinzhong Yao and Paul Badham (University of Wales Press).

- Richard McBrien, The Church: The Evolution of Catholicism (New York: HarperOne, 2008), 6, 281–82, and 356.

- McBrien, Richard P. (1994). Catholicism. HarperCollins. pp. 3–19. ISBN 978-0-06-065405-4.

- Timothy Ware, The Orthodox Church (Oxford: Penguin Books, 1993), 214–217.

- McBrien, pp. 19–20.

- Alden, Henry Mills (1868). "Harper's new monthly magazine". 37 (217–222).

The various Protestant sects can not constitute one church because they have no intercommunion...each Protestant Church, whether Methodist or Baptist or whatever, is in perfect communion with itself everywhere as the Roman Catholic; and in this respect, consequently, the Roman Catholic has no advantage or superiority, except in the point of numbers. As a further necessary consequence, it is plain that the Roman Church is no more Catholic in any sense than a Methodist or a Baptist.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Harper's Magazine. Vol. 37. 1907.

For those who 'belong to the Church,' the term Methodist Catholic, or Presbyterian Catholic, or Baptist Catholic, is as proper as the term Roman Catholic. It simply means that body of Christian believers over the world who agree in their religious views, and accept the same ecclesiastical forms.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Further reading

- Aledo, Roniel (2013). Compendium of the Traditional Catechism of the Catholic Church. Bloomington: iUniverse. ISBN 9781491705766.

- Bavinck, Herman (1992). "The Catholicity of Christianity and the Church" (PDF). Calvin Theological Journal. 27 (2): 220–251.

- Beinert, Wolfgang (1992). "Catholicity as a Property of the Church". The Jurist. 52: 455–483.

- Braaten, Carl E.; Jenson, Robert W., eds. (1996). The Catholicity of the Reformation. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802842206.

- Bossy, John (1982). "Catholicity and nationality in the northern European counter-reformation". Studies in Church History. 18: 285–296. doi:10.1017/S042420840001617X. ISBN 9780631180609. S2CID 159944415.

- Charlesworth, Scott (2012). "Indicators of Catholicity in Early Gospel Manuscripts". The Early Text of the New Testament. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 37–48. ISBN 9780191505041.

- Dulles, Avery (1983). "The Catholicity of the Augsburg Confession". The Journal of Religion. 63 (4): 337–354. doi:10.1086/487060. S2CID 170148693.

- Dulles, Avery (1985). The Catholicity of the Church. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198266761.

- Edwards, Mark J. (2009). Catholicity and Heresy in the Early Church. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754662914.

- Erickson, John H. (1992). "The Local Churches and Catholicity: An Orthodox Perspective". The Jurist. 52: 490–508.

- Fahey, Michael A. (1992). "The Catholicity of the Church in the New Testament and in the Early Patristic Period". The Jurist. 52: 44–70.

- Halleux, André de (1992). "The Catholicity of the local church in the Patriarchate of Antioch after Chalcedon". The Jurist. 52: 109–129.

- Krikorian, Mesrob K. (2010). Christology of the Oriental Orthodox Churches: Christology in the Tradition of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631581216.

- Legrand, Herve (1992). "One Bishop per City: Tensions around the Expression of the Catholicity of the Local Church since Vatican II". The Jurist. 52: 369–400.

- Μαρτζέλος, Γεώργιος Δ. (2009). "Ενότητα και καθολικότητα της Εκκλησίας στο Θεολογικό διάλογο μεταξύ Ορθοδόξου και Ρωμαιοκαθολικής Εκκλησίας" (PDF). Θεολογία. 80 (2): 103–120.

- Meyendorff, John (1966). Orthodoxy and Catholicity. New York: Sheed & Ward.

- Meyendorff, John (1983). Catholicity and the Church. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410068.

- Peri, Vittorio (1992). "Local Churches and Catholicity in the First Millennium of the Roman Tradition". The Jurist. 52: 79–108.

- Provost, James H. (1992). "Local Church and Catholicity in the Constitution Pastor Bonus". The Jurist. 52: 299–334.

- Ratzinger, Joseph; Pera, Marcello (2006). Without Roots: The West, Relativism, Christianity, Islam. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465006342.

- Stewart, Quentin D. (2015). Lutheran Patristic Catholicity: The Vincentian Canon and the Consensus Patrum in Lutheran Orthodoxy. Zürich: LIT Verlag. ISBN 9783643905673.

- Tillard, Jean-Marie R. (1992). "The Local Church Within Catholicity". The Jurist. 52: 448–454.

- Thomas, Joseph (2011). The Catholicity of the Church in the Second Vatican Council. Roma: EDUSC. ISBN 9788883332739.

- Volf, Miroslav (1992). "Catholicity of Two or Three: Free Church Reflections on the Catholicity of the Local Church". The Jurist. 52: 525–546.

External links

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.