Manuel I Komnenos

Manuel I Komnenos (Greek: Μανουήλ Κομνηνός, romanized: Manouíl Komnenos; 28 November 1118 – 24 September 1180), Latinized Comnenus, also called Porphyrogennetos (Greek: Πορφυρογέννητος; "born in the purple"), was a Byzantine emperor of the 12th century who reigned over a crucial turning point in the history of Byzantium and the Mediterranean. His reign saw the last flowering of the Komnenian restoration, during which the Byzantine Empire had seen a resurgence of its military and economic power, and had enjoyed a cultural revival.

| Manuel I Komnenos | |

|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |

Manuscript miniature of Manuel I (part of double portrait with Maria of Antioch, Vatican Library, Rome) | |

| Byzantine emperor | |

| Reign | 8 April 1143 – 24 September 1180 |

| Predecessor | John II Komnenos |

| Successor | Alexios II Komnenos |

| Born | 28 November 1118 |

| Died | 24 September 1180 (aged 61) |

| Spouses | Bertha of Sulzbach Maria of Antioch |

| Issue | Maria Komnene Alexios II Komnenos |

| House | Komnenian dynasty |

| Father | John II Komnenos |

| Mother | Irene of Hungary |

| Religion | Greek Orthodox |

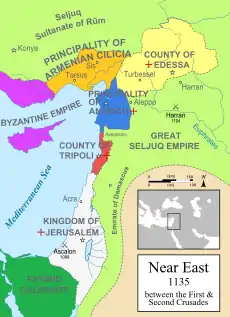

Eager to restore his empire to its past glories as the superpower of the Mediterranean world, Manuel pursued an energetic and ambitious foreign policy. In the process he made alliances with Pope Adrian IV and the resurgent West. He invaded the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, although unsuccessfully, being the last Eastern Roman emperor to attempt reconquests in the western Mediterranean. The passage of the potentially dangerous Second Crusade through his empire was adroitly managed. Manuel established a Byzantine protectorate over the Crusader states of Outremer. Facing Muslim advances in the Holy Land, he made common cause with the Kingdom of Jerusalem and participated in a combined invasion of Fatimid Egypt. Manuel reshaped the political maps of the Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean, placing the kingdoms of Hungary and Outremer under Byzantine hegemony and campaigning aggressively against his neighbours both in the west and in the east.

However, towards the end of his reign, Manuel's achievements in the east were compromised by a serious defeat at Myriokephalon, which in large part resulted from his arrogance in attacking a well-defended Seljuk position. Although the Byzantines recovered and Manuel concluded an advantageous peace with Sultan Kilij Arslan II, Myriokephalon proved to be the final, unsuccessful effort by the empire to recover the interior of Anatolia from the Turks.

Called ho Megas (ὁ Μέγας, translated as "the Great") by the Greeks, Manuel is known to have inspired intense loyalty in those who served him. He also appears as the hero of a history written by his secretary, John Kinnamos, in which every virtue is attributed to him. Manuel, who was influenced by his contact with western Crusaders, enjoyed the reputation of "the most blessed emperor of Constantinople" in parts of the Latin world as well.[1] Modern historians, however, have been less enthusiastic about him. Some of them assert that the great power he wielded was not his own personal achievement, but that of the dynasty he represented; they also argue that, since Byzantine imperial power declined catastrophically after Manuel's death, it is only natural to look for the causes of this decline in his reign.[2]

Accession to the throne

Born on 28 November 1118, Manuel Komnenos was the fourth son of John II Komnenos and Irene of Hungary, so it seemed very unlikely that he would succeed his father.[3] His maternal grandfather was St. Ladislaus. Manuel favourably impressed his father by his courage and fortitude during the unsuccessful Siege of Neocaesarea (1140), against the Danishmendid Turks. In 1143 John II lay dying as a result of an infected wound; on his deathbed he chose Manuel as his successor, in preference to his elder surviving brother Isaac. John cited Manuel's courage and readiness to take advice, in contrast to Isaac's irascibility and unbending pride, as the reasons for his choice. After John died on 8 April 1143,[4] his son, Manuel, was acclaimed emperor by the armies.[5] Yet his succession was by no means assured: with his father's army in the wilds of Cilicia far from Constantinople, he recognised that it was vital he should return to the capital as soon as possible. He still had to take care of his father's funeral, and tradition demanded he organise the foundation of a monastery on the spot where his father died. Swiftly, he dispatched the megas domestikos John Axouch ahead of him, with orders to arrest his most dangerous potential rival, his brother Isaac, who was living in the Great Palace with instant access to the imperial treasure and regalia. Axouch arrived in the capital even before news of the emperor's death had reached it. He quickly secured the loyalty of the city, and when Manuel entered the capital in August 1143, he was crowned by the new patriarch, Michael II Kourkouas. A few days later, with nothing more to fear as his position as emperor was now secure, Manuel ordered the release of Isaac.[6] Then he ordered two golden pieces to be given to every householder in Constantinople and 200 pounds of gold (including 200 silver pieces annually) to be given to the Byzantine Church.[7]

The empire that Manuel inherited from his father was in a more stable position than it had been a century earlier. In the late 11th century, the Byzantine Empire had faced marked military and political decline, but this decline had been arrested and largely reversed by the leadership of Manuel's grandfather and father. Nevertheless, the empire continued to face formidable challenges. At the end of the 11th century, the Normans of Sicily had removed Italy from the control of the Byzantine emperor. The Seljuk Turks had done the same with central Anatolia. And in the Levant, a new force had appeared—the Crusader states—which presented the Byzantine Empire with new challenges. Now, more than at any time during the preceding centuries, the task facing the emperor was daunting indeed.[8]

Second Crusade and Raynald of Châtillon

Prince of Antioch

The first test of Manuel's reign came in 1144, when he was faced with a demand by Raymond, Prince of Antioch for the cession of Cilician territories. However, later that year the crusader County of Edessa was engulfed by the tide of a resurgent Islamic jihad under Imad ad-Din Zengi. Raymond realized that immediate help from the west was out of the question. With his eastern flank now dangerously exposed to this new threat, there seemed little option but for him to prepare for a humiliating visit to Constantinople. Swallowing his pride, he made the journey north to submit to Manuel and ask for protection. He was promised the support that he had requested, and his allegiance to Byzantium was secured.[9]

Expedition against Konya

In 1146 Manuel assembled his army at the military base Lopadion and set out on a punitive expedition against Mas'ud, the Sultan of Rûm, who had been repeatedly violating the frontiers of the Empire in western Anatolia and Cilicia.[10] There was no attempt at a systematic conquest of territory, but Manuel's army defeated the Turks at Acroënus, before capturing and destroying the fortified town of Philomelion, removing its remaining Christian population.[10] The Byzantine forces reached Masud's capital, Konya, and ravaged the area around the city, but could not assault its walls. Among Manuel's motives for mounting this razzia there included a wish to be seen in the West as actively espousing the crusading ideal; Kinnamos also attributed to Manuel a desire to show off his martial prowess to his new bride.[11] While on this campaign Manuel received a letter from Louis VII of France announcing his intention of leading an army to the relief of the crusader states.[12]

Arrival of the Crusaders

Manuel was prevented from capitalising on his conquests by events in the Balkans that urgently required his presence. In 1147 he granted a passage through his dominions to two armies of the Second Crusade under Conrad III of Germany and Louis VII of France. At this time, there were still members of the Byzantine court who remembered the passage of the First Crusade, a defining event in the collective memory of the age that had fascinated Manuel's aunt, Anna Komnene.[13]

Many Byzantines feared the Crusade, a view endorsed by the numerous acts of vandalism and theft practised by the unruly armies as they marched through Byzantine territory. Byzantine troops followed the Crusaders, attempting to police their behaviour, and further troops were assembled in Constantinople, ready to defend the capital against any acts of aggression. This cautious approach was well advised, but still the numerous incidents of covert and open hostility between the Franks and the Greeks on their line of march, for which it seems both sides were to blame, precipitated conflict between Manuel and his guests. Manuel took the precaution—which his grandfather had not taken—of making repairs to the city walls, and he pressed the two kings for guarantees concerning the security of his territories. Conrad's army was the first to enter the Byzantine territory in the summer of 1147, and it figures more prominently in the Byzantine sources, which imply that it was the more troublesome of the two.[a] Indeed, the contemporary Byzantine historian Kinnamos describes a full-scale clash between a Byzantine force and part of Conrad's army, outside the walls of Constantinople. The Byzantines defeated the Germans and, in Byzantine eyes, this reverse caused Conrad to agree to have his army speedily ferried across to Damalis on the Asian shore of the Bosphoros.[14][15]

After 1147, however, the relations between the two leaders became friendlier. By 1148 Manuel had seen the wisdom of securing an alliance with Conrad, whose sister-in-law Bertha of Sulzbach he had earlier married; he actually persuaded the German king to renew their alliance against Roger II of Sicily.[16] Unfortunately for the Byzantine emperor, Conrad died in 1152, and despite repeated attempts, Manuel could not reach an agreement with his successor, Frederick Barbarossa.[b]

Cyprus invaded

Manuel's attention was again drawn to Antioch in 1156, when Raynald of Châtillon, the new Prince of Antioch, claimed that the Byzantine emperor had reneged on his promise to pay him a sum of money and vowed to attack the Byzantine province of Cyprus.[18] Raynald arrested the governor of the island, John Komnenos, who was a nephew of Manuel, and the general Michael Branas.[19] The Latin historian William of Tyre deplored this act of war against fellow Christians and described the atrocities committed by Raynald's men in considerable detail.[20] Having ransacked the island and plundered all its wealth, Raynald's army mutilated the survivors before forcing them to buy back their flocks at exorbitant prices with what little they had left. Thus enriched with enough booty to make Antioch wealthy for years, the invaders boarded their ships and set sail for home.[21] Raynald also sent some of the mutilated hostages to Constantinople as a vivid demonstration of his disobedience and his contempt for the Byzantine emperor.[19]

Manuel responded to this outrage in a characteristically energetic way. In the winter of 1158–59, he marched to Cilicia at the head of a huge army; the speed of his advance (Manuel had hurried on ahead of the main army with 500 cavalry) was such that he managed to surprise the Armenian Thoros of Cilicia, who had participated in the attack on Cyprus.[22] Thoros fled into the mountains, and Cilicia swiftly fell to Manuel.[23]

Manuel in Antioch

Meanwhile, news of the advance of the Byzantine army soon reached Antioch. Raynald knew that he had no hope of defeating the emperor, and in addition knew that he could not expect any aid from King Baldwin III of Jerusalem. Baldwin did not approve of Raynald's attack on Cyprus, and in any case had already made an agreement with Manuel. Thus isolated and abandoned by his allies, Raynald decided that abject submission was his only hope. He appeared dressed in a sack with a rope tied around his neck, and begged for forgiveness. Manuel at first ignored the prostrate Raynald, chatting with his courtiers; William of Tyre commented that this ignominious scene continued for so long that all present were "disgusted" by it.[24] Eventually, Manuel forgave Raynald on condition that he would become a vassal of the Empire, effectively surrendering the independence of Antioch to Byzantium.[3]

Peace having been restored, a grand ceremonial procession was staged on 12 April 1159 for the triumphant entry of the Byzantine army into the city, with Manuel riding through the streets on horseback, while the Prince of Antioch and the King of Jerusalem followed on foot. Manuel dispensed justice to the citizens and presided over games and tournaments for the crowd. In May, at the head of a united Christian army, he started on the road to Edessa, but he abandoned the campaign when he secured the release by Nur ad-Din, the ruler of Syria, of 6,000 Christian prisoners captured in various battles since the second Crusade.[25] Despite the glorious end of the expedition, modern scholars argue that Manuel ultimately achieved much less than he had desired in terms of imperial restoration.[c]

Satisfied with his efforts thus far, Manuel headed back to Constantinople. On their way back, his troops were surprised in line of march by the Turks. Despite this, they won a complete victory, routing the enemy army from the field and inflicting heavy losses. In the following year, Manuel drove the Turks out of Isauria.[26]

Italian campaign

Roger II of Sicily

In 1147 Manuel was faced with war by Roger II of Sicily, whose fleet had captured the Byzantine island of Corfu and plundered Thebes and Corinth. However, despite being distracted by a Cuman attack in the Balkans, in 1148 Manuel enlisted the alliance of Conrad III of Germany, and the help of the Venetians, who quickly defeated Roger with their powerful fleet. In 1149, Manuel recovered Corfu and prepared to take the offensive against the Normans, while Roger II sent George of Antioch with a fleet of 40 ships to pillage Constantinople's suburbs.[27] Manuel had already agreed with Conrad on a joint invasion and partition of southern Italy and Sicily. The renewal of the German alliance remained the principal orientation of Manuel's foreign policy for the rest of his reign, despite the gradual divergence of interests between the two empires after Conrad's death.[16]

Roger died in February 1154 and was succeeded by William I, who faced widespread rebellions against his rule in Sicily and Apulia, leading to the presence of Apulian refugees at the Byzantine court. Conrad's successor, Frederick Barbarossa, launched a campaign against the Normans, but his expedition stalled. These developments encouraged Manuel to take advantage of the multiple instabilities on the Italian peninsula.[28] He sent Michael Palaiologos and John Doukas, both of whom held the high imperial rank of sebastos, with Byzantine troops, ten ships and large quantities of gold to invade Apulia in 1155.[29] The two generals were instructed to enlist the support of Frederick, but he declined because his demoralised army longed to get back north of the Alps as soon as possible.[b] Nevertheless, with the help of disaffected local barons, including Count Robert of Loritello, Manuel's expedition achieved astonishingly rapid progress as the whole of southern Italy rose up in rebellion against the Sicilian Crown and the untried William I.[16] There followed a string of spectacular successes as numerous strongholds yielded either to force or the lure of gold.[25]

Papal-Byzantine alliance

The city of Bari, which had been the capital of the Byzantine Catapanate of Italy for centuries before the arrival of the Normans, opened its gates to the Emperor's army, and the overjoyed citizens tore down the Norman citadel. After the fall of Bari, the cities of Trani, Giovinazzo, Andria, Taranto and Brindisi were also captured. William arrived with his army, including 2,000 knights, but was heavily defeated.[30]

Encouraged by the success, Manuel dreamed of restoration of the Roman Empire, at the cost of union between the Orthodox and the Catholic Church, a prospect which would frequently be offered to the Pope during negotiations and plans for alliance.[31] If there was ever a chance of reuniting the eastern and western churches, and coming to reconciliation with the Pope permanently, this was probably the most favourable moment. The Papacy was never on good terms with the Normans, except when under duress by the threat of direct military action. Having the "civilised" Byzantines on its southern border was infinitely preferable to the Papacy than having to constantly deal with the troublesome Normans of Sicily. It was in the interest of Pope Adrian IV to reach a deal if at all possible, since doing so would greatly increase his own influence over the entire Orthodox Christian population. Manuel offered a large sum of money to the Pope for the provision of troops, with the request that the Pope grant the Byzantine emperor lordship of three maritime cities in return for assistance in expelling William from Sicily. Manuel also promised to pay 5,000 pounds of gold to the Pope and the Curia.[32] Negotiations were hurriedly carried out, and an alliance was formed between Manuel and Hadrian.[28]

| "Alexios Komnenos and Doukas ... had become captive to the Normans' lord [and] again ruined matters. For as they had already pledged to the Sicilians many things not then desired by the emperor, they robbed the Romans of very great and noble achievements. [They] ... very likely deprived the Roman of the cities too soon." |

| John Cinnamus[33] |

At this point, just as the war seemed decided in his favour, events turned against Manuel. Byzantine commander Michael Palaiologos alienated allies with his attitude, stalling the campaign as Count Robert III of Loritello refused to speak to him. Although the two were reconciled, the campaign had lost some of its momentum: Michael was soon recalled to Constantinople, and his loss was a major blow to the campaign. The turning point was the Battle of Brindisi, where the Normans launched a major counter-attack by both land and sea. At the approach of the enemy, the mercenaries that had been hired with Manuel's gold demanded huge increases in their pay. When this was refused, they deserted. Even the local barons started to melt away, and soon John Doukas was left hopelessly outnumbered. The arrival of Alexios Komnenos Bryennios with some ships failed to retrieve the Byzantine position.[d] The naval battle was decided in favour of the Normans, while John Doukas and Alexios Bryennios (along with four Byzantine ships) were captured.[34] Manuel then sent Alexios Axouch to Ancona to raise another army, but by this time William had already retaken all of the Byzantine conquests in Apulia. The defeat at Brindisi put an end to the restored Byzantine reign in Italy; in 1158 the Byzantine army left Italy and never returned again.[35] Both Nicetas Choniates and Kinnamos, the major Byzantine historians of this period, agree, however, that the peace terms Axouch secured from William allowed Manuel to extricate himself from the war with dignity, despite a devastating raid by a Norman fleet of 164 ships (carrying 10,000 men) on Euboea and Almira in 1156.[36]

Failure of the Church union

.png.webp)

During the Italian campaign, and afterwards, during the struggle of the Papal Curia with Frederick, Manuel tried to sway the popes with hints of a possible union between the Eastern and Western churches. Although in 1155 Pope Adrian IV had expressed his eagerness to prompt the reunion of the churches,[e] hopes for a lasting Papal-Byzantine alliance came up against insuperable problems. Adrian IV and his successors demanded recognition of their religious authority over all Christians everywhere and sought superiority over the Byzantine emperor; they were not at all willing to fall into a state of dependence from one emperor to the other.[31] Manuel, on the other hand, wanted an official recognition of his secular authority over both East and West.[37] Such conditions would not be accepted by either side. Even if a pro-western emperor such as Manuel agreed, the Greek citizens of the empire would have rejected outright any union of this sort, as they did almost three hundred years later when the Orthodox and Catholic churches were briefly united under the pope. In spite of his friendliness towards the Roman Church and his cordial relations with all the popes, Manuel was never honoured with the title of augustus by the popes. And although he twice sent embassies to Pope Alexander III (in 1167 and 1169) offering to reunite the Greek and Latin churches, Alexander refused, under pretext of the troubles that would follow union.[38]

The final results of the Italian campaign were limited in terms of the advantages gained by the Empire. The city of Ancona became a Byzantine base in Italy, accepting Manuel as sovereign. The Normans of Sicily had been damaged and now came to terms with the Empire, ensuring peace for the rest of Manuel's reign. The Empire's ability to get involved in Italian affairs had been demonstrated. However, given the enormous quantities of gold which had been lavished on the project, it also demonstrated the limits of what money and diplomacy alone could achieve. The expense of Manuel's involvement in Italy must have cost the treasury a great deal (probably more than 2.16 million hyperpyra or 30,000 pounds of gold), and yet it produced only limited solid gains.[39][40]

Byzantine policy in Italy after 1158

After 1158, under the new conditions, the aims of the Byzantine policy changed. Manuel now decided to oppose the objective of the Hohenstaufen dynasty to directly annex Italy, which Frederick believed should acknowledge his power. When the war between Frederick Barbarossa and the northern Italian communes started, Manuel actively supported the Lombard League with money subsidies, agents, and, occasionally, troops.[41] The walls of Milan, demolished by the Germans, were restored with Manuel's aid.[42] Ancona remained important as a centre of Byzantine influence in Italy. The Anconitans made a voluntary submission to Manuel, and the Byzantines maintained representatives in the city.[43] Frederick's defeat at the Battle of Legnano, on 29 May 1176, seemed rather to improve Manuel's position in Italy. According to Kinnamos, Cremona, Pavia and a number of other "Ligurian" cities went over to Manuel;[44] his relations were also particularly favourable in regard to Genoa and Pisa, but not to Venice. In March 1171 Manuel had suddenly broken with Venice, ordering all 20,000 Venetians on imperial territory to be arrested and their property confiscated.[45] Venice, incensed, sent a fleet of 120 ships against Byzantium. Due to an epidemic, and pursued by 150 Byzantine ships, the fleet was forced to return without great success.[46] In all probability, friendly relations between Byzantium and Venice were not restored in Manuel's lifetime.[31]

Balkan frontier

On his northern frontier Manuel expended considerable effort to preserve the conquests made by Basil II over one hundred years earlier and maintained, sometimes tenuously, ever since. Due to distraction from his neighbours on the Balkan frontier, Manuel was kept from his main objective, the subjugation of the Normans of Sicily. Relations had been good with the Serbs and Hungarians since 1129, so the Serb rebellion came as a shock. The Serbs of Rascia, being so induced by Roger II of Sicily, invaded Byzantine territory in 1149.[3]

Manuel forced the rebellious Serbs, and their leader, Uroš II, to vassalage (1150–1152).[47] He then made repeated attacks upon the Hungarians with a view to annexing their territory along the Sava. In the wars of 1151–1153 and 1163–1168 Manuel led his troops into Hungary and a spectacular raid deep into enemy territory yielded substantial war booty. In 1167, Manuel sent 15,000 men under the command of Andronikos Kontostephanos against the Hungarians,[48] scoring a decisive victory at the Battle of Sirmium and enabling the Empire to conclude a very advantageous peace with the Kingdom of Hungary by which Syrmia, Bosnia and Dalmatia were ceded. By 1168 nearly the whole of the eastern Adriatic coast lay in Manuel's hands.[49]

Efforts were also made towards a diplomatic annexation of Hungary. The Hungarian heir Béla, younger brother of the Hungarian king Stephen III, was sent to Constantinople to be educated in the emperor's court. Manuel intended the youth to marry his daughter, Maria, and to make him his heir, thus securing the union of Hungary with the Empire. At court Béla assumed the name Alexius and received the title of despot, which had previously been applied only to the emperor himself. However, two unforeseen dynastic events drastically altered the situation. In 1169, Manuel's young wife gave birth to a son, thus depriving Béla of his status as heir of the Byzantine throne (although Manuel would not renounce the Croatian lands he had taken from Hungary). Then, in 1172, Stephen died childless, and Béla went home to take his throne. Before leaving Constantinople, he swore a solemn oath to Manuel that he would always "keep in mind the interests of the emperor and of the Romans". Béla III kept his word: as long as Manuel lived, he made no attempt to retrieve his Croatian inheritance, which he only afterwards reincorporated into Hungary.[49]

Relations with Kievan Rus' (Russia)

Manuel Komnenos attempted to draw the Russian principalities into his net of diplomacy directed against Hungary, and to a lesser extent Norman Sicily. This polarised the Russian princes into pro- and anti-Byzantine camps. In the late 1140s three princes were competing for primacy in Russia: prince Iziaslav II of Kiev was related to Géza II of Hungary and was hostile to Byzantium; Prince Yuri Dolgoruki of Suzdal was Manuel's ally (symmachos), and Vladimirko of Galicia is described as Manuel's vassal (hypospondos). Galicia was situated on the northern and north-eastern borders of Hungary and, therefore, was of great strategic importance in the Byzantine-Hungarian conflicts. Following the deaths of both Iziaslav and Vladimirko, the situation became reversed; when Yuri of Suzdal, Manuel's ally, took over Kiev and Yaroslav, the new ruler of Galicia, adopted a pro-Hungarian stance.[50]

In 1164–65 Manuel's cousin Andronikos, the future emperor, escaped from captivity in Byzantium and fled to the court of Yaroslav in Galicia. This situation, holding out the alarming prospect of Andronikos making a bid for Manuel's throne sponsored by both Galicia and Hungary, spurred the Byzantines into an unprecedented flurry of diplomacy. Manuel pardoned Andronikos and persuaded him to return to Constantinople in 1165. A mission to Kiev, then ruled by Prince Rostislav, resulted in a favourable treaty and a pledge to supply the Empire with auxiliary troops; Yaroslav of Galicia was also persuaded to renounce his Hungarian connections and return fully into the imperial fold. As late as 1200 the princes of Galicia were providing invaluable services against the enemies of the Empire, at that time the Cumans.[51]

The restoration of relations with Galicia had an immediate benefit for Manuel when, in 1166, he dispatched two armies to attack the eastern provinces of Hungary in a vast pincer movement. One army crossed the Walachian Plain and entered Hungary through the Transylvanian Alps (Southern Carpathians), while the other army made a wide circuit to Galicia and, with Galician aid, crossed the Carpathian Mountains. Since the Hungarians had most of their forces concentrated on the Sirmium and Belgrade frontier, they were caught off guard by the Byzantine invasion; this resulted in the Hungarian province of Transylvania being thoroughly ravaged by the Byzantine armies.[52]

Invasion of Egypt

Alliance with the Kingdom of Jerusalem

Control of Egypt was a decades-old dream of the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, and its king Amalric I needed all the military and financial support he could get for his planned campaign.[53] Amalric also realised that if he were to pursue his ambitions in Egypt, he might have to leave Antioch to the hegemony of Manuel, who had paid 100,000 dinars for the release of Bohemond III.[54][55] In 1165, he sent envoys to the Byzantine court to negotiate a marriage alliance (Manuel had already married Amalric's cousin Maria of Antioch in 1161).[56] After a long interval of two years, Amalric married Manuel's grandniece Maria Komnene in 1167, and "swore all that his brother Baldwin had sworn before."[f] A formal alliance was negotiated in 1168, whereby the two rulers arranged for a conquest and partition of Egypt, with Manuel taking the coastal area, and Amalric the interior. In the autumn of 1169 Manuel sent a joint expedition with Amalric to Egypt: a Byzantine army and a naval force of 20 large warships, 150 galleys, and 60 transports, under the command of the megas doux Andronikos Kontostephanos, joined forces with Amalric at Ascalon.[56][57] William of Tyre, who negotiated the alliance, was impressed in particular by the large transport ships that were used to transport the cavalry forces of the army.[58]

Although such a long-range attack on a state far from the centre of the Empire may seem extraordinary (the last time the Empire had attempted anything on this scale was the failed invasion of Sicily over one hundred and twenty years earlier), it can be explained in terms of Manuel's foreign policy, which was to use the Latins to ensure the survival of the Empire. This focus on the bigger picture of the eastern Mediterranean and even further afield thus led Manuel to intervene in Egypt: it was believed that in the context of the wider struggle between the crusader states and the Islamic powers of the east, control of Egypt would be the deciding factor. It had become clear that the ailing Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt held the key to the fate of the crusader states. If Egypt came out of its isolation and joined forces with the Muslims under Nur ad-Din, the crusader cause was in trouble.[53]

A successful invasion of Egypt would have several further advantages for the Byzantine Empire. Egypt was a rich province, and in the days of the Roman Empire it had supplied much of the grain for Constantinople before it was lost to the Arabs in the 7th century. The revenues that the Empire could have expected to gain from the conquest of Egypt would have been considerable, even if these would have to be shared with the Crusaders. Furthermore, Manuel may have wanted to encourage Amalric's plans, not only to deflect the ambitions of the Latins away from Antioch, but also to create new opportunities for joint military ventures that would keep the King of Jerusalem in his debt, and would also allow the Empire to share in territorial gains.[53]

Failure of the expedition

The joined forces of Manuel and Amalric laid siege to Damietta on 27 October 1169, but the siege was unsuccessful due to the failure of the Crusaders and the Byzantines to co-operate fully.[59] According to Byzantine forces, Amalric, not wanting to share the profits of victory, dragged out the operation until the emperor's men ran short of provisions and were particularly affected by famine; Amalric then launched an assault, which he promptly aborted by negotiating a truce with the defenders. On the other hand, William of Tyre remarked that the Greeks were not entirely blameless.[60] Whatever the truth of the allegations of both sides, when the rains came, both the Latin army and the Byzantine fleet returned home, although half of the Byzantine fleet was lost in a sudden storm.[61]

Despite the bad feelings generated at Damietta, Amalric still refused to abandon his dream of conquering Egypt, and he continued to seek good relations with the Byzantines in the hopes of another joined attack, which never took place.[62] In 1171 Amalric came to Constantinople in person, after Egypt had fallen to Saladin. Manuel was thus able to organise a grand ceremonial reception which both honoured Amalric and underlined his dependence: for the rest of Amalric's reign, Jerusalem was a Byzantine satellite, and Manuel was able to act as a protector of the Holy Places, exerting a growing influence in the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[63] In 1177, a fleet of 150 ships was sent by Manuel I to invade Egypt, but returned home after appearing off Acre due to the refusal of Count Philip of Flanders and many important nobles of the Kingdom of Jerusalem to help.[64]

Kilij Arslan II and the Seljuk Turks

Between 1158 and 1162, a series of Byzantine campaigns against the Seljuk Turks of the Sultanate of Rûm resulted in a treaty favourable to the Empire. According to the agreement, certain frontier regions, including the city of Sivas, should be handed over to Manuel in return for some quantity of cash, while it also obliged the Seljuk Sultan Kilij Arslan II to recognize his overlordship.[41][65] Kilij Arslan II used the peace with Byzantium, and the power vacuum caused by the death in 1174 of Nur ad-Din Zangi the ruler of Syria, to expel the Danishmends from their Anatolian emirates. When the Seljuk sultan refused to cede some of the territory he had taken from the Danishmends to the Byzantines, as he was obliged to do as part of his treaty obligations, Manuel decided that it was time to deal with the Turks once and for all.[41][66][67] Therefore, he assembled the full imperial army and marched against the Seljuk capital, Iconium (Konya).[41] Manuel's strategy was to prepare the advanced bases of Dorylaeum and Sublaeum, and then to use them to strike as quickly as possible at Iconium.[68]

Yet Manuel's army of 35,000 men was large and unwieldy—according to a letter that Manuel sent to King Henry II of England, the advancing column was ten miles (16 km) long.[69] Manuel marched against Iconium via Laodicea, Chonae, Lampe, Celaenae, Choma and Antioch. Just outside the entrance to the pass at Myriokephalon, Manuel was met by Turkish ambassadors, who offered peace on generous terms. Most of Manuel's generals and experienced courtiers urged him to accept the offer. The younger and more aggressive members of the court urged Manuel to attack, however, and he took their advice and continued his advance.[25]

Manuel made serious tactical errors, such as failing to properly scout out the route ahead.[70] These failings caused him to lead his forces straight into a classic ambush. On 17 September 1176 Manuel was checked by Seljuk Sultan Kilij Arslan II at the Battle of Myriokephalon (in highlands near the Tzibritze pass), in which his army was ambushed while marching through the narrow mountain pass.[41][71] The Byzantines were hemmed in by the narrowness of the pass, this allowed the Seljuks to concentrate their attacks on part of the Byzantine army, especially the baggage and siege train, without the rest being able to intervene.[72] The army's siege equipment was quickly destroyed, and Manuel was forced to withdraw—without siege engines, the conquest of Iconium was impossible. According to Byzantine sources, Manuel lost his nerve both during and after the battle, fluctuating between extremes of self-delusion and self-abasement;[73] according to William of Tyre, he was never the same again.

The terms by which Kilij Arslan II allowed Manuel and his army to leave were that he should remove his forts and armies on the frontier at Dorylaeum and Sublaeum. Since the Sultan had already failed to keep his side of the earlier treaty of 1162, however, Manuel only ordered the fortifications of Sublaeum to be dismantled, but not the fortifications of Dorylaeum.[74] Nevertheless, defeat at Myriokephalon was an embarrassment for both Manuel personally and also for his empire. The Komnenian emperors had worked hard since the Battle of Manzikert, 105 years earlier, to restore the reputation of the empire. Yet because of his over-confidence, Manuel had demonstrated to the whole world that Byzantium still could not decisively defeat the Seljuks, despite the advances made during the past century. In western opinion, Myriokephalon cut Manuel down to a humbler size: not that of Emperor of the Romans but that of King of the Greeks.[71]

The defeat at Myriokephalon has often been depicted as a catastrophe in which the entire Byzantine army was destroyed. Manuel himself compared the defeat to Manzikert; it seemed to him that the Byzantine defeat at Myriokephalon complemented the destruction at Manzikert. In reality, although a defeat, it was not too costly and did not significantly diminish the Byzantine army.[71] Most of the casualties were borne by the right wing, largely composed of allied troops commanded by Baldwin of Antioch, and also by the baggage train, which was the main target of the Turkish ambush.[75]

The limited losses inflicted on native Byzantine troops were quickly recovered, and in the following year Manuel's forces defeated a force of "picked Turks".[68] John Komnenos Vatatzes, who was sent by the Emperor to repel the Turkish invasion, not only brought troops from the capital but also was able to gather an army along the way. Vatatzes caught the Turks in an ambush as they were crossing the Meander River; the subsequent Battle of Hyelion and Leimocheir effectively destroyed them as a fighting force. This is an indication that the Byzantine army remained strong and that the defensive program of western Asia Minor was still successful.[76] After the victory on the Meander, Manuel himself advanced with a small army to drive the Turks from Panasium, south of Cotyaeum.[74]

In 1178, however, a Byzantine army retreated after encountering a Turkish force at Charax, allowing the Turks to capture many livestock.[3] The city of Claudiopolis in Bithynia was besieged by the Turks in 1179, forcing Manuel to lead a small cavalry force to save the city, and then, even as late as 1180, the Byzantines succeeded in scoring a victory over the Turks.[3]

The continuous warfare had a serious effect upon Manuel's vitality; he declined in health and in 1180 succumbed to a slow fever. Furthermore, like Manzikert, the balance between the two powers began to gradually shift—Manuel never again attacked the Turks, and after his death they began to move further west, deeper into Byzantine territory.

Doctrinal controversies (1156–1180)

Three major theological controversies occurred during Manuel's reign. In 1156–1157 the question was raised whether Christ had offered himself as a sacrifice for the sins of the world to the Father and to the Holy Spirit only, or also to the Logos (i.e., to himself).[77] In the end a synod held at Constantinople in 1157 adopted a compromise formula, that the Word made flesh offered a double sacrifice to the Holy Trinity, despite the dissidence of Patriarch of Antioch-elect Soterichus Panteugenus.[3]

Ten years later, a controversy arose as to whether the saying of Christ, "My Father is greater than I", referred to his divine nature, to his human nature, or to the union of the two.[77] Demetrius of Lampe, a Byzantine diplomat recently returned from the West, ridiculed the way the verse was interpreted there, that Christ was inferior to his father in his humanity but equal in his divinity. Manuel, on the other hand, perhaps with an eye on the project for Church union, found that the formula made sense, and prevailed over a majority in a synod convened on 2 March 1166 to decide the issue, where he had the support of the patriarch Luke Chrysoberges[3] and later Patriarch Michael III.[78] Those who refused to submit to the synod's decisions had their property confiscated or were exiled.[g] The political dimensions of this controversy are apparent from the fact that a leading dissenter from the Emperor's doctrine was his nephew Alexios Kontostephanos.[79]

A third controversy sprung up in 1180, when Manuel objected to the formula of solemn abjuration, which was exacted from Muslim converts. One of the more striking anathemas of this abjuration was that directed against the deity worshipped by Muhammad and his followers:[80]

And before all, I anathematize the God of Muhammad about whom he [Muhammad] says, "He is God alone, God made of solid, hammer-beaten metal; He begets not and is not begotten, nor is there like unto Him any one."

The emperor ordered the deletion of this anathema from the Church's catechetical texts, a measure that provoked vehement opposition from both the Patriarch and bishops.[80]

Chivalric narrations

Manuel is representative of a new kind of Byzantine ruler who was influenced by his contact with western Crusaders. He arranged jousting matches, even participating in them, an unusual and discomforting sight for the Byzantines. Endowed with a fine physique, Manuel has been the subject of exaggeration in the Byzantine sources of his era, where he is presented as a man of great personal courage. According to the story of his exploits, which appear as a model or a copy of the romances of chivalry, such was his strength and exercise in arms that Raymond of Antioch was incapable of wielding his lance and buckler. In a famous tournament, he is said to have entered the lists on a fiery courser, and to have overturned two of the stoutest Italian knights. In one day, he is said to have slain forty Turks with his own hand, and in a battle against the Hungarians he allegedly snatched a banner, and was the first, almost alone, who passed a bridge that separated his army from the enemy. On another occasion, he is said to have cut his way through a squadron of five hundred Turks, without receiving a wound; he had previously posted an ambuscade in a wood and was accompanied only by his brother and Axouch.[81]

Family

Manuel had two wives. His first marriage, in 1146, was to Bertha of Sulzbach, a sister-in-law of Conrad III of Germany. She died in 1159. Children:

Manuel's second marriage was to Maria of Antioch (nicknamed Xene), a daughter of Raymond and Constance of Antioch, in 1161. By this marriage, Manuel had one son:

- Alexios II Komnenos, who succeeded as emperor in 1180.[83]

Manuel had several illegitimate children:

By Theodora Vatatzina:

- Alexios Komnenos (born in the early 1160s), who was recognised as the emperor's son, and indeed received a title (sebastokrator). He was briefly married to Eirene Komnene, illegitimate daughter of Andronikos I Komnenos, in 1183–1184, and was then blinded by his father-in-law. He lived until at least 1191 and was known personally to Choniates.[84]

By Maria Taronitissa, the wife of John Doukas Komnenos:

- Alexios Komnenos, a pinkernes ("cupbearer"), who fled Constantinople in 1184 and was a figurehead of the Norman invasion and the siege of Thessalonica in 1185.

By other lovers:

- A daughter whose name is unknown. She was born around 1150 and married Theodore Maurozomes before 1170. Her son was Manuel Maurozomes, whose daughter married Kaykhusraw I, the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm, and her descendants ruled the sultanate from 1220–1246.[85]

- A daughter whose name is unknown, born around 1155. She was the maternal grandmother of the author Demetrios Tornikes.[86]

Assessments

Foreign and military affairs

As a young man, Manuel had been determined to restore by force of arms the predominance of the Byzantine Empire in the Mediterranean countries. By the time he died in 1180, 37 years had passed since that momentous day in 1143 when, amid the wilds of Cilicia, his father had proclaimed him emperor. These years had seen Manuel involved in conflict with his neighbours on all sides. Manuel's father and grandfather before him had worked patiently to undo the damage done by the battle of Manzikert and its aftermath. Thanks to their efforts, the empire Manuel inherited was stronger and better organised than at any time for a century. While it is clear that Manuel used these assets to the full, it is not so clear how much he added to them, and there is room for doubt as to whether he used them to best effect.[1]

| "The most singular feature in the character of Manuel is the contrast and vicissitude of labour and sloth, of hardiness and effeminacy. In war he seemed ignorant of peace, in peace he appeared incapable of war." |

| Edward Gibbon[87] |

Manuel had proven himself to be an energetic emperor who saw possibilities everywhere, and whose optimistic outlook had shaped his approach to foreign policy. However, in spite of his military prowess Manuel achieved but a slight degree of his object of restoring the Byzantine Empire. Retrospectively, some commentators have criticised some of Manuel's aims as unrealistic, in particular citing the expeditions he sent to Egypt as proof of dreams of grandeur on an unattainable scale. His greatest military campaign, his grand expedition against the Turkish Sultanate of Iconium, ended in humiliating defeat, and his greatest diplomatic effort apparently collapsed, when Pope Alexander III became reconciled to the German emperor Frederick Barbarossa at the Peace of Venice. Historian Mark C. Bartusis argues that Manuel (and his father as well) tried to rebuild a national army, but his reforms were adequate for neither his ambitions nor his needs; the defeat at Myriokephalon underscored the fundamental weakness of his policies.[88] According to Edward Gibbon, Manuel's victories were not productive of any permanent or useful conquest.[87]

His advisors on western church affairs included the Pisan scholar Hugh Eteriano.

Internal affairs

Choniates criticised Manuel for raising taxes and pointed to Manuel's reign as a period of excess; according to Choniates, the money thus raised was spent lavishly at the cost of his citizens. Whether one reads the Greek encomiastic sources, or the Latin and oriental sources, the impression is consistent with Choniates' picture of an emperor who spent lavishly in all available ways, rarely economising in one sector in order to develop another.[26] Manuel spared no expense on the army, the navy, diplomacy, ceremonial, palace-building, the Komnenian family, and other seekers of patronage. A significant amount of this expenditure was pure financial loss to the Empire, like the subsidies poured into Italy and the crusader states, and the sums spent on the failed expeditions of 1155–1156, 1169 and 1176.[89]

The problems this created were counterbalanced to some extent by his successes, particularly in the Balkans; Manuel extended the frontiers of his Empire in the Balkan region, ensuring security for the whole of Greece and Bulgaria. Had he been more successful in all his ventures, he would have controlled not only the most productive farmland around the Eastern Mediterranean and Adriatic seas, but also the entire trading facilities of the area. Even if he did not achieve his ambitious goals, his wars against Hungary brought him control of the Dalmatian coast, the rich agricultural region of Sirmium, and the Danube trade route from Hungary to the Black Sea. His Balkan expeditions are said to have taken great booty in slaves and livestock;[90] Kinnamos was impressed by the amount of arms taken from the Hungarian dead after the battle of 1167.[91] And even if Manuel's wars against the Turks probably realised a net loss, his commanders took livestock and captives on at least two occasions.[90]

This allowed the Western provinces to flourish in an economic revival that had begun in the time of his grandfather Alexios I and continued till the close of the century. Indeed, it has been argued that Byzantium in the 12th century was richer and more prosperous than at any time since the Persian invasion during the reign of Herakleios, some five hundred years earlier. There is good evidence from this period of new construction and new churches, even in remote areas, strongly suggesting that wealth was widespread.[92] Trade was also flourishing; it has been estimated that the population of Constantinople, the biggest commercial centre of the Empire, was between half a million and one million during Manuel's reign, making it by far the largest city in Europe. A major source of Manuel's wealth was the kommerkion, a customs duty levied at Constantinople on all imports and exports.[93] The kommerkion was stated to have collected 20,000 hyperpyra each day.[94]

Furthermore, Constantinople was undergoing expansion. The cosmopolitan character of the city was being reinforced by the arrival of Italian merchants and Crusaders en route to the Holy Land. The Venetians, the Genoese, and others opened up the ports of the Aegean to commerce, shipping goods from the Crusader kingdoms of Outremer and Fatimid Egypt to the west and trading with Byzantium via Constantinople.[95] These maritime traders stimulated demand in the towns and cities of Greece, Macedonia, and the Greek Islands, generating new sources of wealth in a predominantly agrarian economy.[96] Thessaloniki, the second city of the Empire, hosted a famous summer fair that attracted traders from across the Balkans and even further afield to its bustling market stalls. In Corinth, silk production fuelled a thriving economy. All this is a testament to the success of the Komnenian Emperors in securing a Pax Byzantina in these heartland territories.[92]

Legacy

To the rhetors of his court, Manuel was the "divine emperor". A generation after his death, Choniates referred to him as "the most blessed among emperors", and a century later John Stavrakios described him as "great in fine deeds". John Phokas, a soldier who fought in Manuel's army, characterised him some years later as the "world saving" and glorious emperor.[97] Manuel would be remembered in France, Italy, and the Crusader states as the most powerful sovereign in the world.[3] A Genoese analyst noted that with the passing of "Lord Manuel of divine memory, the most blessed emperor of Constantinople ... all Christendom incurred great ruin and detriment."[98] William of Tyre called Manuel "a wise and discreet prince of great magnificence, worthy of praise in every respect", "a great-souled man of incomparable energy", whose "memory will ever be held in benediction." Manuel was further extolled by Robert of Clari as "a right worthy man, [...] and richest of all the Christians who ever were, and the most bountiful."[99]

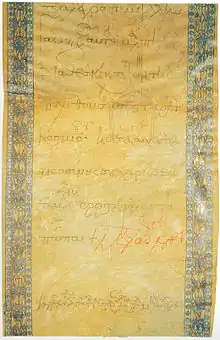

A telling reminder of the influence that Manuel held in the Crusader states in particular can still be seen in the church of the Holy Nativity in Bethlehem. In the 1160s the nave was redecorated with mosaics showing the councils of the church.[100] Manuel was one of the patrons of the work. On the south wall, an inscription in Greek reads: "the present work was finished by Ephraim the monk, painter and mosaicist, in the reign of the great emperor Manuel Porphyrogennetos Komnenos and in the time of the great king of Jerusalem, Amalric." That Manuel's name was placed first was a symbolic, public recognition of Manuel's overlordship as leader of the Christian world. Manuel's role as protector of the Orthodox Christians and Christian holy places in general is also evident in his successful attempts to secure rights over the Holy Land. Manuel participated in the building and decorating of many of the basilicas and Greek monasteries in the Holy Land, including the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, where thanks to his efforts the Byzantine clergy were allowed to perform the Greek liturgy each day. All this reinforced his position as overlord of the Crusader states, with his hegemony over Antioch and Jerusalem secured by agreement with Raynald, Prince of Antioch, and Amalric, King of Jerusalem respectively. Manuel was also the last Byzantine emperor who, thanks to his military and diplomatic success in the Balkans, could call himself "ruler of Dalmatia, Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia, Bulgaria and Hungary".[101]

Manuel died on 24 September 1180,[102] having just celebrated the betrothal of his son Alexios II to the daughter of the king of France.[103] He was laid to rest alongside his father in the Pantokrator Monastery in Constantinople.[104] Thanks to the diplomacy and campaigning of Alexios, John and Manuel, the empire was a great power, economically prosperous, and secure on its frontiers; but there were serious problems as well. Internally, the Byzantine court required a strong leader to hold it together, and after Manuel's death stability was seriously endangered from within. Some of the foreign enemies of the Empire were lurking on the flanks, waiting for a chance to attack, in particular the Turks in Anatolia, whom Manuel had ultimately failed to defeat, and the Normans in Sicily, who had already tried but failed to invade the Empire on several occasions. Even the Venetians, the single most important western ally of Byzantium, were on bad terms with the empire at Manuel's death in 1180. Given this situation, it would have taken a strong emperor to secure the Empire against the foreign threats it now faced, and to rebuild the depleted imperial treasury. But Manuel's son was a minor, and his unpopular regency government was overthrown in a violent coup d'état. This troubled succession weakened the dynastic continuity and solidarity on which the strength of the Byzantine state had come to rely.[103]

See also

- List of Byzantine emperors

Notes

^ a: The mood that prevailed before the end of 1147 is best conveyed by a verse encomium to Manuel (one of the poems included in a list transmitted under the name of Theodore Prodromos in Codex Marcianus graecus XI.22 known as Manganeios Prodromos), which was probably an imperial commission, and must have been written shortly after the Germans had crossed the Bosporus. Here Conrad is accused of wanting to take Constantinople by force, and to install a Latin patriarch (Manganeios Prodromos, no 20.1).[105]

^ b: According to Paul Magdalino, one of Manuel's primary goals was a partition of Italy with the German empire, in which Byzantium would get the Adriatic coast. His unilateral pursuit, however, antagonized the new German emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, whose own plans for imperial restoration ruled out any partnership with Byzantium. Manuel was thus obliged to treat Frederick as his main enemy, and to form a web of relationships with other western powers, including the papacy, his old enemy, the Norman kingdom, Hungary, several magnates and cities throughout Italy, and, above all, the crusader states.[103]

^ c: Magdalino underscores that, whereas John had removed the Rupenid princes from power in Cilicia twenty years earlier, Manuel allowed Toros to hold most of his strongholds he had taken, and effectively restored only the coastal area to imperial rule. From Raynald, Manuel secured recognition of imperial suzerainty over Antioch, with the promise to hand over the citadel, to instal a patriarch sent from Constantinople (not actually implemented until 1165–66), and to provide troops for the emperor's service, but nothing seems to have been said about the reversion of Antioch to direct imperial rule. According to Magdalino, this suggests that Manuel had dropped this demand on which both his grandfather and father insisted.[22] For his part, historian Zachary Nugent Brooke believes that the victory of Christianity against Nur ad-Din was made impossible, since both Greeks and Latins were concerned primarily with their own interests. He characterises the policy of Manuel as "short-sighted", because "he lost a splendid opportunity of recovering the former possessions of the Empire, and by his departure threw away most of the actual fruits of his expedition".[106] According to Piers Paul Read, Manuel's deal with Nur ad-Din was for the Latins another expression of Greeks' perfidy.[19]

^ d: Alexios had been ordered to bring soldiers, but he merely brought his empty ships to Brindisi.[34]

^ e: In 1155 Hadrian sent legates to Manuel, with a letter for Basil, Archbishop of Thessaloniki, in which he exhorted that bishop to procure the reünion of the churches. Basil answered that there was no division between the Greeks and Latins, since they held the same faith and offered the same sacrifice. "As for the causes of scandal, weak in themselves, that have separated us from each other", he added, "your Holiness can cause them to cease, by your own extended authority and the help of the Emperor of the West."[107]

^ f: This probably meant that Amalric repeated Baldwin's assurances regarding the status of Antioch as an imperial fief.[56]

^ g: According to Michael Angold, after the controversy of 1166 Manuel took his responsibilities very seriously, and tightened his grip over the church. 1166 was also the year in which Manuel first referred in his legislation to his role as the disciplinarian of the church (epistemonarkhes).[108]

References

- P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 3

- P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 3–4

- A. Stone (2007) Manuel I Comnenus. DIR

- John Kinnamos (c. 1118) History I.10. Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae XIII. "Ioannes post diebus moritus... octavo die mensis".

- Gibbon, The decline and fall of the Roman Empire, 72

- Gibbon, The decline and fall of the Roman Empire, 72

* J. H. Norwich, A short history of Byzantium

* A. Stone, Manuel I Comnenus - J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall, 87–88

- "Byzantium". Papyros-Larousse-Britannica. 2006.

- J. Cinnamus, Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus, 33–35

* P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 40 - W. Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, 640

- J. Cinnamus, Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus, 47

* P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 42 - Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, p. 42

- A. Komnene, The Alexiad, 333

- Kinnamos, pp. 65–67

- Birkenmeier, p. 110

- P. Magdalino, The Byzantine Empire, 621

- Letter by the Emperor Manuel I Komnenos Archived 2 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Vatican Secret Archives.

- P. P. Read, The Templars, 238

- P. P. Read, The Templars, 239

- William of Tyre, Historia, XVIII, 10

- C. Hillenbrand, The Imprisonment of Raynald of Châtillon, 80

* T. F. Madden, The New Concise History of the Crusades, 65 - P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 67

- Jeffreys, Elizabeth; Jeffreys, Michael (2015) "A Constantinopolitan Poet Views Frankish Antioch". In: Chrissis, Nikolaos G.; Kedar, Benjamin Z.; Phillips, Jonathan (eds.) Crusades, Ashgate, ISBN 978-1-472-46841-3, vol. 14, p. 53

- B. Hamilton, William of Tyre and the Byzantine Empire, 226

* William of Tyre, Historia, XVIII, 23 - Z. N. Brooke, A History of Europe, from 911 to 1198, 482

* P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 67

* J. H. Norwich, A short history of Byzantium - K. Paparrigopoulos, History of the Greek Nation, Db, 134

- J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall, 98 and 103

- J. Duggan, The Pope and the Princes, 122

- J. W. Birkenmeier, The Development of the Komnenian Army, 114

* J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall, 112 - J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall, 112–113

- A. A. Vasiliev, History of the Byzantine Empire, VII

- William of Tyre, Historia, XVIII, 2

- J. Cinnamus, Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus, 172

- J. W. Birkenmeier, The Development of the Komnenian Army, 115

* J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall, 115 - J. W. Birkenmeier, The Development of the Komnenian Army, 115–116

* A. A. Vasiliev, History of the Byzantine Empire, VII - J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall, 116

* P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 61 - J. W. Birkenmeier, The Development of the Komnenian Army, 114

- Abbé Guettée, The Papacy, Chapter VII

* J. W. Birkenmeier, The Development of the Komnenian Army, 114 - J. Birkenmeier, The Development of the Komnenian Army, 116

- W. Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, 643

- Rogers, Clifford J, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology: Vol. 1., 290

- P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 84

* A. A. Vasiliev, History of the Byzantine Empire, VII - Abulafia, D. (1984) Ancona, Byzantium and the Adriatic, 1155–1173, Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 52, pp. 195–216, 211

- J. Cinnamus, Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus, 231

* P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 84 - P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 93

- J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall, 131

- Curta, Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, xxiii

- J. W. Birkenmeier, The Development of the Komnenian Army, 241

- J. W. Sedlar, East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 372

- D. Obolensky, The Byzantine Commonwealth, 299–300.

- D. Obolensky, The Byzantine Commonwealth, 300–302.

- M. Angold, The Byzantine Empire, 1025–1204, 177.

- P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 73

- J. Harris, Byzantium and The Crusades, 107

- P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 73

* J. G. Rowe, Alexander III and the Jerusalem Crusade, 117 - P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 74

- J. Phillips, The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople, 158

- William of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea

- R. Rogers, Latin Siege Warfare in the Twelfth Century, 84–86

- William of Tyre, Historia, XX 15–17

- T. F. Madden, The New Concise History of the Crusades, 68

- T. F. Madden, The New Concise History of the Crusades, 68–69

- P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 75

* H. E. Mayer, The Latin East, 657 - J. Harris, Byzantium and The Crusades, 109

- I. Health, Byzantine Armies, 4

- Magdalino, pp. 78 and 95–96

- K. Paparrigopoulos, History of the Greek Nation, Db, 140

- J. W. Birkenmeier, The Development of the Komnenian Army, 128

- Birkenmeier, p. 132.

- J. Bradbury, Medieval Warfare, 176

- D. MacGillivray Nicol, Byzantium and Venice, 102

- Haldon 2001, pp. 142–143

- P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 98

- W. Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, 649

- J. W. Birkenmeier, The Development of the Komnenian Army, 128

* K. Paparrigopoulos, History of the Greek Nation, Db, 141 - J. W. Birkenmeier, The Development of the Komnenian Army, 196

- J. H. Kurtz, History of the Christian Church to the Restoration, 265–266

- P. Magdalino, p. 279.

- P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 217

- G. L. Hanson, Manuel I Komnenos and the "God of Muhammad", 55

- Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 73

* K. Paparrigopoulos, History of the Greek Nation, Db, 121 - Garland-Stone, Bertha-Irene of Sulzbach, first wife of Manuel I Comnenus

- K. Varzos, Genealogy of the Komnenian Dynasty, 155

- Každan-Epstein, Change in Byzantine Culture, 102

- C. M. Brand, The Turkish Element in Byzantium, 12

* P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 98 - K. Varzos, Genealogy of the Komnenian Dynasty, 157a

- Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, p. 74.

- M. Bartusis, The Late Byzantine Army, 5–6

- N. Choniates, O City of Byzantium, Annals of Niketas Choniates, 96–97

* P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 173 - P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 174

- J. Cinnamus, Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus, 274

- M. Angold, The Byzantine Empire, 1025–1204

- J. Harris, Byzantium and the Crusades, 25

- J. Harris, Byzantium and the Crusades, 26

- G. W. Day, Manuel and the Genoese, 289–290

- P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 143–144

- J. Harris, Byzantium and the Crusades

* P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 3 - G. W. Day, Manuel and the Genoese, 289–290

* P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 3 - Robert of Clari, "Account of the Fourth Crusade", 18 Archived 13 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- B. Zeitler, Cross-cultural interpretations

- J. W. Sedlar, East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 372–373

- Schreiner, Peter (1975). Die byzantinischen Kleinchroniken 1. Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae XII(1). p. 146. Chronik 14, 80, 4: "κδ' [24] τού σεπτεμβρίου μηνός, τής ιδ' [14] ίνδικτίώvoς, ςχπθ' [6689] έτους".

- P. Magdalino, The Medieval Empire, 194

- Melvani, N., (2018) 'The tombs of the Palaiologan emperors', Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 42 (2) pp.237-260

- Jeffreys-Jeffreys, The "Wild Beast from the West", 102

* P. Magdalino, The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 49 - Z. N. Brooke, A History of Europe, from 911 to 1198, 482

- Abbé Guettée, The Papacy, Chapter VII

- M. Angold, Church and Society under the Komneni, 99

Sources

Primary sources

- Choniates, Nicetas (1984). O City of Byzantium, Annals of Niketas Choniatēs. Translated by Harry J. Magoulias. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1764-2.

- Cinammus, John, Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus, trans. Charles M. Brand. Columbia University Press, 1976.

- Komnene (Comnena), Anna; Edgar Robert Ashton Sewter (1969). "XLVIII: The First Crusade". The Alexiad of Anna Comnena translated by Edgar Robert Ashton Sewter. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044215-4.

- Robert of Clari (c. 1208). Account of the Fourth Crusade.

- William of Tyre, Historia Rerum in Partibus Transmarinis Gestarum (A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea), translated by E. A. Babock and A. C. Krey (Columbia University Press, 1943). See the original text in the Latin library.

Secondary sources

- Abbé Guettée (1866). "Chapter VII". The Papacy: Its Historic Origin and Primitive Relations with the Eastern Churches. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009.

- Angold, Michael (1995). "Church and Politics under Manuel I Komnenos". Church and Society in Byzantium Under the Comneni, 1081–1261. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26432-4.

- Angold, Michael (1997). The Byzantine Empire, 1025–1204. Longman. ISBN 0-582-29468-1.

- Birkenmeier, John W. (2002). "The Campaigns of Manuel I Komnenos". The Development of the Komnenian Army: 1081–1180. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-11710-5.

- Bradbury, Jim (2006). "Military events". The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Read Country Books. ISBN 1-84664-983-8.

- Brand, Charles M. (1989). "The Turkish Element in Byzantium, Eleventh-Twelfth Centuries". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. 43: 1–25. doi:10.2307/1291603. JSTOR 1291603.

- Brooke, Zachary Nugent (2004). "East and West: 1155–1198". A History of Europe, from 911 to 1198. Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-415-22126-9.

- "Byzantium". Papyros-Larousse-Britannica (Volume XIII) (in Greek). 2006. ISBN 960-8322-84-7.

- Curta, Florin (2006). "Chronology". Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0.

- Day, Gerald. W. (June 1977). "Manuel and the Genoese: A Reappraisal of Byzantine Commercial Policy in the Late Twelfth Century". The Journal of Economic History. 37 (2): 289–301. doi:10.1017/S0022050700096947. S2CID 155065665.

- Duggan, Anne J. (2003). "The Pope and the Princes". Adrian IV, the English Pope, 1154–1159: Studies and Texts edited by Brenda Bolton and Anne J. Duggan. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-0708-9.

- Garland, Lynda, Stone, Andrew. "Bertha-Irene of Sulzbach, first wife of Manuel I Comnenus". Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- Gibbon, Edward (1995). "XLVIII: The Decline and Fall". The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Volume III). Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-043395-3.

- Haldon, John (2001), The Byzantine Wars, Stroud: Tempus, ISBN 0-7524-1777-0

- Hamilton, Bernard (2003). "William of Tyre and the Byzantine Empire". Porphyrogenita: : Essays on the History and Literature of Byzantium and the Latin East in Honor of Julian Chrysostomides, edited by Charalambos Dendrinos, Jonathan Harris, Eirene Harvalia-Crook and Judith Herrin. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-3696-8.

- Hanson, Graig L. (2003). "Manuel I Komnenos and the "God of Muhammad": A Study in Byzantine Ecclesiastical Politics". Medieval Christian Perceptions of Islam: A Book of Essays edited by John Tolan. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92892-3.

- Harris, Jonathan, Byzantium and the Crusades, Bloomsbury, 2nd ed., 2014. ISBN 978-1-78093-767-0

- Harris, Jonathan and Tolstoy, Dmitri, 'Alexander III and Byzantium', in Alexander III (1159–81: The Art of Survival, ed. P. Clarke and A. Duggan, Ashgate, 2012, pp. 301–13. ISBN 978 07546 6288 4

- Harris, Jonathan (2017). Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4742-5467-0.

- Heath, Ian (1995). Byzantine Armies 1118–1461 AD (Illustrated by Angus McBride). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-347-8.

- Hillenbrand, Carole (2003). "The Imprisonment of Raynald of Châtillon". Texts, Documents, and Artefacts: Islamic Studies in Honour of D. S. (Donald Sidney) Richards edited by Chase F. Robinson. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-10865-3.

- Jeffreys, Elizabeth; Jeffreys Michael (2001). "The "Wild Beast from the West": Immediate Literary Reactions in Byzantium to the Second Crusade" (PDF). The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World edited by Angeliki E. Laiou and Roy Parviz Mottahedeh. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 0-88402-277-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017.

- Každan, Alexander P.; Epstein, Ann Wharton (1990). "Popular and Aristocratic Popular Trends". Change in Byzantine Culture in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06962-5.

- Kurtz, Johann Heinrich (1860). "Dogmatic Controversies, 12th and 14th Centuries". History of the Christian Church to the Reformation. T. & T. Clark. ISBN 0-548-06187-4.

- "Letter by the Emperor Manuel I Komnenos To Pope Eugene III on the Issue of the Crusades". Vatican Secret Archives. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- Madden, Thomas F. (2005). "The Decline of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade". The New Concise History of the Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-3822-2.

- Magdalino, Paul (2004). "The Byzantine Empire (1118–1204)". In Luscombe, David; Riley-Smith, Jonathan (eds.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 4, c.1024–c.1198, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 611–643. ISBN 9781139054027.

- Magdalino, Paul (2002). "The Medieval Empire (780–1204)". The Oxford History of Byzantium By Cyril A. Mango. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814098-3.

- Magdalino, Paul (2002) [1993]. The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143–1180. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52653-1.

- Mayer, Hans (2004). "The Latin East, 1098–1205". In Luscombe, David; Riley-Smith, Jonathan (eds.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 4, c.1024–c.1198, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 644–674. ISBN 9781139054027.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1988). "The Parting of the Ways". Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34157-4.

- Norwich, John Julius (1998). A Short History of Byzantium. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-025960-0.

- Norwich, John J. (1995). Byzantium: The Decline and Fall. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0-679-41650-1.

- Obolensky, Dimitri (1971). The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe 500–1453. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 1-84212-019-0.

- Paparrigopoulos, Constantine; Karolidis, Pavlos (1925). History of the Hellenic Nation (in Greek). Vol. Db. Athens: Eleftheroudakis..

- Read, Piers Paul (2003) [1999]. The Templars (translated in Greek by G. Kousounelou). Enalios. ISBN 960-536-143-4.

- Rogers, Clifford J. (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology: Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195334036.

- Rogers, Randal (1997). "The Capture of the Palestinian Coast". Latin Siege Warfare in the Twelfth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820689-5.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). "Foreign Affairs". East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97290-4.

- Stone, Andrew. "Manuel I Comnenus (A.D. 1143–1180)". Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- Varzos, Konstantinos (1984). Η Γενεαλογία των Κομνηνών [The Genealogy of the Komnenoi] (PDF) (in Greek). Vol. A. Thessaloniki: Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Thessaloniki. OCLC 834784634.

- Vasiliev, Alexander Alexandrovich (1928–1935). "Byzantium and the Crusades". History of the Byzantine Empire. ISBN 0-299-80925-0.

- Zeitler, Barbara (1994). "Cross-cultural Interpretations of Imagery in the Middle Ages". The Art Bulletin. 76 (4): 680–694. doi:10.2307/3046063. JSTOR 3046063.