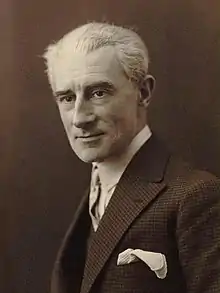

Maurice Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel[n 1] (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In the 1920s and 1930s Ravel was internationally regarded as France's greatest living composer.

Born to a music-loving family, Ravel attended France's premier music college, the Paris Conservatoire; he was not well regarded by its conservative establishment, whose biased treatment of him caused a scandal. After leaving the conservatoire, Ravel found his own way as a composer, developing a style of great clarity and incorporating elements of modernism, baroque, neoclassicism and, in his later works, jazz. He liked to experiment with musical form, as in his best-known work, Boléro (1928), in which repetition takes the place of development. Renowned for his abilities in orchestration, Ravel made some orchestral arrangements of other composers' piano music, of which his 1922 version of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition is the best known.

A slow and painstaking worker, Ravel composed fewer pieces than many of his contemporaries. Among his works to enter the repertoire are pieces for piano, chamber music, two piano concertos, ballet music, two operas and eight song cycles; he wrote no symphonies or church music. Many of his works exist in two versions: first, a piano score and later an orchestration. Some of his piano music, such as Gaspard de la nuit (1908), is exceptionally difficult to play, and his complex orchestral works such as Daphnis et Chloé (1912) require skilful balance in performance.

Ravel was among the first composers to recognise the potential of recording to bring their music to a wider public. From the 1920s, despite limited technique as a pianist or conductor, he took part in recordings of several of his works; others were made under his supervision.

Life and career

Early years

Ravel was born in the Basque town of Ciboure, France, near Biarritz, 18 kilometres (11 mi) from the Spanish border. His father, Pierre-Joseph Ravel, was an educated and successful engineer, inventor and manufacturer, born in Versoix near the Franco-Swiss border.[4][n 2] His mother, Marie, née Delouart, was Basque but had grown up in Madrid. In 19th-century terms, Joseph had married beneath his status – Marie was illegitimate and barely literate – but the marriage was a happy one.[7] Some of Joseph's inventions were successful, including an early internal combustion engine and a notorious circus machine, the "Whirlwind of Death", an automotive loop-the-loop that was a major attraction until a fatal accident at Barnum and Bailey's Circus in 1903.[8]

Both Ravel's parents were Roman Catholics; Marie was also something of a free-thinker, a trait inherited by her elder son.[9] He was baptised in the Ciboure parish church six days after he was born. The family moved to Paris three months later, and there a younger son, Édouard, was born. (He was close to his father, whom he eventually followed into the engineering profession.)[10] Maurice was particularly devoted to their mother; her Basque-Spanish heritage was a strong influence on his life and music.[11] Among his earliest memories were folk songs she sang to him.[10] The household was not rich, but the family was comfortable, and the two boys had happy childhoods.[12]

Ravel senior delighted in taking his sons to factories to see the latest mechanical devices, but he also had a keen interest in music and culture in general.[13] In later life, Ravel recalled, "Throughout my childhood I was sensitive to music. My father, much better educated in this art than most amateurs are, knew how to develop my taste and to stimulate my enthusiasm at an early age."[14] There is no record that Ravel received any formal general schooling in his early years; his biographer Roger Nichols suggests that the boy may have been chiefly educated by his father.[15]

When he was seven, Ravel started piano lessons with Henri Ghys, a friend of Emmanuel Chabrier; five years later, in 1887, he began studying harmony, counterpoint and composition with Charles-René, a pupil of Léo Delibes.[15] Without being anything of a child prodigy, he was a highly musical boy.[16] Charles-René found that Ravel's conception of music was natural to him "and not, as in the case of so many others, the result of effort".[17] Ravel's earliest known compositions date from this period: variations on a chorale by Schumann, variations on a theme by Grieg and a single movement of a piano sonata.[18] They survive only in fragmentary form.[19]

In 1888 Ravel met the young pianist Ricardo Viñes, who became not only a lifelong friend, but also one of the foremost interpreters of his works, and an important link between Ravel and Spanish music.[20] The two shared an appreciation of Wagner, Russian music, and the writings of Poe, Baudelaire and Mallarmé.[21] At the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889, Ravel was much struck by the new Russian works conducted by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.[22] This music had a lasting effect on both Ravel and his older contemporary Claude Debussy, as did the exotic sound of the Javanese gamelan, also heard during the Exposition.[18]

Émile Decombes took over as Ravel's piano teacher in 1889; in the same year Ravel gave his earliest public performance.[23] Aged fourteen, he took part in a concert at the Salle Érard along with other pupils of Decombes, including Reynaldo Hahn and Alfred Cortot.[24]

Paris Conservatoire

With the encouragement of his parents, Ravel applied for entry to France's most important musical college, the Conservatoire de Paris. In November 1889, playing music by Chopin, he passed the examination for admission to the preparatory piano class run by Eugène Anthiome.[25] Ravel won the first prize in the Conservatoire's piano competition in 1891, but otherwise he did not stand out as a student.[26] Nevertheless, these years were a time of considerable advance in his development as a composer. The musicologist Arbie Orenstein writes that for Ravel the 1890s were a period "of immense growth ... from adolescence to maturity".[27]

In 1891 Ravel progressed to the classes of Charles-Wilfrid de Bériot, for piano, and Émile Pessard, for harmony.[23] He made solid, unspectacular progress, with particular encouragement from Bériot but, in the words of the musicologist Barbara L. Kelly, he "was only teachable on his own terms".[28] His later teacher Gabriel Fauré understood this, but it was not generally acceptable to the conservative faculty of the Conservatoire of the 1890s.[28] Ravel was expelled in 1895, having won no more prizes.[n 3] His earliest works to survive in full are from these student days: Sérénade grotesque, for piano, and "Ballade de la Reine morte d'aimer",[n 4] a mélodie setting a poem by Roland de Marès (both 1893).[18]

Ravel was never so assiduous a student of the piano as his colleagues such as Viñes and Cortot were.[n 5] It was plain that as a pianist he would never match them, and his overriding ambition was to be a composer.[26] From this point he concentrated on composition. His works from the period include the songs "Un grand sommeil noir" and "D'Anne jouant de l'espinette" to words by Paul Verlaine and Clément Marot,[18][n 6] and the piano pieces Menuet antique and Habanera (for four hands), the latter eventually incorporated into the Rapsodie espagnole.[31] At around this time, Joseph Ravel introduced his son to Erik Satie, who was earning a living as a café pianist. Ravel was one of the first musicians – Debussy was another – who recognised Satie's originality and talent.[32] Satie's constant experiments in musical form were an inspiration to Ravel, who counted them "of inestimable value".[33]

In 1897 Ravel was readmitted to the Conservatoire, studying composition with Fauré, and taking private lessons in counterpoint with André Gedalge.[23] Both these teachers, particularly Fauré, regarded him highly and were key influences on his development as a composer.[18] As Ravel's course progressed, Fauré reported "a distinct gain in maturity ... engaging wealth of imagination".[34] Ravel's standing at the Conservatoire was nevertheless undermined by the hostility of the Director, Théodore Dubois, who deplored the young man's musically and politically progressive outlook.[35] Consequently, according to a fellow student, Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi, he was "a marked man, against whom all weapons were good".[36] He wrote some substantial works while studying with Fauré, including the overture Shéhérazade and a violin sonata, but he won no prizes, and therefore was expelled again in 1900. As a former student he was allowed to attend Fauré's classes as a non-participating "auditeur" until finally abandoning the Conservatoire in 1903.[37]

In May 1897 Ravel conducted the first performance of the Shéhérazade overture, which had a mixed reception, with boos mingling with applause from the audience, and unflattering reviews from the critics. One described the piece as "a jolting debut: a clumsy plagiarism of the Russian School" and called Ravel a "mediocrely gifted debutant ... who will perhaps become something if not someone in about ten years, if he works hard".[38][n 7] Another critic, Pierre Lalo, thought that Ravel showed talent, but was too indebted to Debussy and should instead emulate Beethoven.[40] Over the succeeding decades Lalo became Ravel's most implacable critic.[40] In 1899 Ravel composed his first piece to become widely known, though it made little impact initially: Pavane pour une infante défunte ("Pavane for a dead princess").[41] It was originally a solo piano work, commissioned by the Princesse de Polignac.[42][n 8]

From the start of his career, Ravel appeared calmly indifferent to blame or praise. Those who knew him well believed that this was no pose but wholly genuine.[43] The only opinion of his music that he truly valued was his own, perfectionist and severely self-critical.[44] At twenty years of age he was, in the words of the biographer Burnett James, "self-possessed, a little aloof, intellectually biased, given to mild banter".[45] He dressed like a dandy and was meticulous about his appearance and demeanour.[46] Orenstein comments that, short in stature,[n 9] light in frame and bony in features, Ravel had the "appearance of a well-dressed jockey", whose large head seemed suitably matched to his formidable intellect.[47] During the late 1890s and into the early years of the next century, Ravel was bearded in the fashion of the day; from his mid-thirties he was clean-shaven.[48]

Les Apaches and Debussy

Around 1900 Ravel and a number of innovative young artists, poets, critics and musicians joined together in an informal group; they came to be known as Les Apaches ("The Hooligans"), a name coined by Viñes to represent their status as "artistic outcasts".[49] They met regularly until the beginning of the First World War, and members stimulated one another with intellectual argument and performances of their works. The membership of the group was fluid, and at various times included Igor Stravinsky and Manuel de Falla as well as their French friends.[n 10]

Among the enthusiasms of the Apaches was the music of Debussy. Ravel, twelve years his junior, had known Debussy slightly since the 1890s, and their friendship, though never close, continued for more than ten years.[51] In 1902 André Messager conducted the premiere of Debussy's opera Pelléas et Mélisande at the Opéra-Comique. It divided musical opinion. Dubois unavailingly forbade Conservatoire students to attend, and the conductor's friend and former teacher Camille Saint-Saëns was prominent among those who detested the piece.[52] The Apaches were loud in their support.[53] The first run of the opera consisted of fourteen performances: Ravel attended all of them.[54]

Debussy was widely held to be an Impressionist composer – a label he intensely disliked. Many music lovers began to apply the same term to Ravel, and the works of the two composers were frequently taken as part of a single genre.[55] Ravel thought that Debussy was indeed an Impressionist but that he himself was not.[56][n 11] Orenstein comments that Debussy was more spontaneous and casual in his composing while Ravel was more attentive to form and craftsmanship.[58] Ravel wrote that Debussy's "genius was obviously one of great individuality, creating its own laws, constantly in evolution, expressing itself freely, yet always faithful to French tradition. For Debussy, the musician and the man, I have had profound admiration, but by nature I am different from Debussy ... I think I have always personally followed a direction opposed to that of [his] symbolism."[59] During the first years of the new century Ravel's new works included the piano piece Jeux d'eau[n 12] (1901), the String Quartet and the orchestral song cycle Shéhérazade (both 1903).[60] Commentators have noted some Debussian touches in some parts of these works. Nichols calls the quartet "at once homage to and exorcism of Debussy's influence".[61]

The two composers ceased to be on friendly terms in the middle of the first decade of the 1900s, for musical and possibly personal reasons. Their admirers began to form factions, with adherents of one composer denigrating the other. Disputes arose about the chronology of the composers' works and who influenced whom.[51] Prominent in the anti-Ravel camp was Lalo, who wrote, "Where M. Debussy is all sensitivity, M. Ravel is all insensitivity, borrowing without hesitation not only technique but the sensitivity of other people."[62] The public tension led to personal estrangement.[62] Ravel said, "It's probably better for us, after all, to be on frigid terms for illogical reasons."[63] Nichols suggests an additional reason for the rift. In 1904 Debussy left his wife and went to live with the singer Emma Bardac. Ravel, together with his close friend and confidante Misia Edwards and the opera star Lucienne Bréval, contributed to a modest regular income for the deserted Lilly Debussy, a fact that Nichols suggests may have rankled with her husband.[64]

Scandal and success

During the first years of the new century Ravel made five attempts to win France's most prestigious prize for young composers, the Prix de Rome, past winners of which included Berlioz, Gounod, Bizet, Massenet and Debussy.[65] In 1900 Ravel was eliminated in the first round; in 1901 he won the second prize for the competition.[66] In 1902 and 1903 he won nothing: according to the musicologist Paul Landormy, the judges suspected Ravel of making fun of them by submitting cantatas so academic as to seem like parodies.[60][n 13] In 1905 Ravel, by now thirty, competed for the last time, inadvertently causing a furore. He was eliminated in the first round, which even critics unsympathetic to his music, including Lalo, denounced as unjustifiable.[68] The press's indignation grew when it emerged that the senior professor at the Conservatoire, Charles Lenepveu, was on the jury, and only his students were selected for the final round;[69] his insistence that this was pure coincidence was not well received.[70] L'affaire Ravel became a national scandal, leading to the early retirement of Dubois and his replacement by Fauré, appointed by the government to carry out a radical reorganisation of the Conservatoire.[71]

Among those taking a close interest in the controversy was Alfred Edwards, owner and editor of Le Matin, for which Lalo wrote. Edwards was married to Ravel's friend Misia;[n 14] the couple took Ravel on a seven-week Rhine cruise on their yacht in June and July 1905, the first time he had travelled abroad.[73]

By the latter part of the 1900s Ravel had established a pattern of writing works for piano and subsequently arranging them for full orchestra.[74] He was in general a slow and painstaking worker, and reworking his earlier piano compositions enabled him to increase the number of pieces published and performed.[75] There appears to have been no mercenary motive for this; Ravel was known for his indifference to financial matters.[76] The pieces that began as piano compositions and were then given orchestral dress were Pavane pour une infante défunte (orchestrated 1910), Une barque sur l'océan (1906, from the 1905 piano suite Miroirs), the Habanera section of Rapsodie espagnole (1907–08), Ma mère l'Oye (1908–10, orchestrated 1911), Valses nobles et sentimentales (1911, orchestrated 1912), Alborada del gracioso (from Miroirs, orchestrated 1918) and Le tombeau de Couperin (1914–17, orchestrated 1919).[18]

Ravel was not by inclination a teacher, but he gave lessons to a few young musicians he felt could benefit from them. Manuel Rosenthal was one, and records that Ravel was a very demanding teacher when he thought his pupil had talent. Like his own teacher, Fauré, he was concerned that his pupils should find their own individual voices and not be excessively influenced by established masters.[77] He warned Rosenthal that it was impossible to learn from studying Debussy's music: "Only Debussy could have written it and made it sound like only Debussy can sound."[78] When George Gershwin asked him for lessons in the 1920s, Ravel, after serious consideration, refused, on the grounds that they "would probably cause him to write bad Ravel and lose his great gift of melody and spontaneity".[79][n 15] The best-known composer who studied with Ravel was probably Ralph Vaughan Williams, who was his pupil for three months in 1907–08. Vaughan Williams recalled that Ravel helped him escape from "the heavy contrapuntal Teutonic manner ... Complexe mais pas compliqué was his motto."[81]

Vaughan Williams's recollections throw some light on Ravel's private life, about which the latter's reserved and secretive personality has led to much speculation. Vaughan Williams, Rosenthal and Marguerite Long have all recorded that Ravel frequented brothels;[82] Long attributed this to his self-consciousness about his diminutive stature, and consequent lack of confidence with women.[76] By other accounts, none of them first-hand, Ravel was in love with Misia Edwards,[72] or wanted to marry the violinist Hélène Jourdan-Morhange.[83] Rosenthal records and discounts contemporary speculation that Ravel, a lifelong bachelor, may have been homosexual.[84] Such speculation recurred in a 2000 life of Ravel by Benjamin Ivry;[85] subsequent studies have concluded that Ravel's sexuality and personal life remain a mystery.[86]

Ravel's first concert outside France was in 1909. As the guest of the Vaughan Williamses, he visited London, where he played for the Société des Concerts Français, gaining favourable reviews and enhancing his growing international reputation.[87][n 16]

1910 to First World War

The Société Nationale de Musique, founded in 1871 to promote the music of rising French composers, had been dominated since the mid-1880s by a conservative faction led by Vincent d'Indy.[89] Ravel, together with several other former pupils of Fauré, set up a new, modernist organisation, the Société Musicale Indépendente, with Fauré as its president.[n 17] The new society's inaugural concert took place on 20 April 1910; the seven items on the programme included premieres of Fauré's song cycle La chanson d'Ève, Debussy's piano suite D'un cahier d'esquisses, Zoltán Kodály's Six pièces pour piano and the original piano duet version of Ravel's Ma mère l'Oye. The performers included Fauré, Florent Schmitt, Ernest Bloch, Pierre Monteux and, in the Debussy work, Ravel.[91] Kelly considers it a sign of Ravel's new influence that the society featured Satie's music in a concert in January 1911.[18]

The first of Ravel's two operas, the one-act comedy L'heure espagnole[n 18] was premiered in 1911. The work had been completed in 1907, but the manager of the Opéra-Comique, Albert Carré, repeatedly deferred its presentation. He was concerned that its plot – a bedroom farce – would be badly received by the ultra-respectable mothers and daughters who were an important part of the Opéra-Comique's audience.[92] The piece was only modestly successful at its first production, and it was not until the 1920s that it became popular.[93]

In 1912 Ravel had three ballets premiered. The first, to the orchestrated and expanded version of Ma mère l'Oye, opened at the Théâtre des Arts in January.[94] The reviews were excellent: the Mercure de France called the score "absolutely ravishing, a masterwork in miniature".[95] The music rapidly entered the concert repertoire; it was played at the Queen's Hall, London, within weeks of the Paris premiere, and was repeated at the Proms later in the same year. The Times praised "the enchantment of the work ... the effect of mirage, by which something quite real seems to float on nothing".[96] New York audiences heard the work in the same year.[97] Ravel's second ballet of 1912 was Adélaïde ou le langage des fleurs, danced to the score of Valses nobles et sentimentales, which opened at the Châtelet in April. Daphnis et Chloé opened at the same theatre in June. This was his largest-scale orchestral work, and took him immense trouble and several years to complete.[98]

Daphnis et Chloé was commissioned in or about 1909 by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev for his company, the Ballets Russes.[n 19] Ravel began work with Diaghilev's choreographer, Michel Fokine, and designer, Léon Bakst.[100] Fokine had a reputation for his modern approach to dance, with individual numbers replaced by continuous music. This appealed to Ravel, and after discussing the action in great detail with Fokine, Ravel began composing the music.[101] There were frequent disagreements between the collaborators, and the premiere was under-rehearsed because of the late completion of the work.[102] It had an unenthusiastic reception and was quickly withdrawn, although it was revived successfully a year later in Monte Carlo and London.[103] The effort to complete the ballet took its toll on Ravel's health;[n 20] neurasthenia obliged him to rest for several months after the premiere.[105]

Ravel composed little during 1913. He collaborated with Stravinsky on a performing version of Mussorgsky's unfinished opera Khovanshchina, and his own works were the Trois poèmes de Mallarmé for soprano and chamber ensemble, and two short piano pieces, À la manière de Borodine and À la manière de Chabrier.[23] In 1913, together with Debussy, Ravel was among the musicians present at the dress rehearsal of The Rite of Spring.[106] Stravinsky later said that Ravel was the only person who immediately understood the music.[107] Ravel predicted that the premiere of the Rite would be seen as an event of historic importance equal to that of Pelléas et Mélisande.[108][n 21]

War

When Germany invaded France in 1914 Ravel tried to join the French Air Force. He considered his small stature and light weight ideal for an aviator, but was rejected because of his age and a minor heart complaint.[110] While waiting to be enlisted, Ravel composed Trois Chansons, his only work for a cappella choir, setting his own texts in the tradition of French 16th-century chansons. He dedicated the three songs to people who might help him to enlist.[111] After several unsuccessful attempts to enlist, Ravel finally joined the Thirteenth Artillery Regiment as a lorry driver in March 1915, when he was forty.[112] Stravinsky expressed admiration for his friend's courage: "at his age and with his name he could have had an easier place, or done nothing".[113] Some of Ravel's duties put him in mortal danger, driving munitions at night under heavy German bombardment. At the same time his peace of mind was undermined by his mother's failing health. His own health also deteriorated; he suffered from insomnia and digestive problems, underwent a bowel operation following amoebic dysentery in September 1916, and had frostbite in his feet the following winter.[114]

During the war, the Ligue Nationale pour la Defense de la Musique Française was formed by Saint-Saëns, Dubois, d'Indy and others, campaigning for a ban on the performance of contemporary German music.[115] Ravel declined to join, telling the committee of the league in 1916, "It would be dangerous for French composers to ignore systematically the productions of their foreign colleagues, and thus form themselves into a sort of national coterie: our musical art, which is so rich at the present time, would soon degenerate, becoming isolated in banal formulas."[116] The league responded by banning Ravel's music from its concerts.[117]

Ravel's mother died in January 1917, and he fell into a "horrible despair", compounding the distress he felt at the suffering endured by the people of his country during the war.[118] He composed few works in the war years. The Piano Trio was almost complete when the conflict began, and the most substantial of his wartime works is Le tombeau de Couperin, composed between 1914 and 1917. The suite celebrates the tradition of François Couperin, the 18th-century French composer; each movement is dedicated to a friend of Ravel's who died in the war.[119]

1920s

After the war, those close to Ravel recognised that he had lost much of his physical and mental stamina. As the musicologist Stephen Zank puts it, "Ravel's emotional equilibrium, so hard won in the previous decade, had been seriously compromised."[120] His output, never large, became smaller.[120] Nonetheless, after the death of Debussy in 1918, he was generally seen, in France and abroad, as the leading French composer of the era.[121] Fauré wrote to him, "I am happier than you can imagine about the solid position which you occupy and which you have acquired so brilliantly and so rapidly. It is a source of joy and pride for your old professor."[121] Ravel was offered the Legion of Honour in 1920,[n 22] and although he declined the decoration, he was viewed by the new generation of composers typified by Satie's protégés Les Six as an establishment figure. Satie had turned against him, and commented, "Ravel refuses the Légion d'honneur, but all his music accepts it."[124][n 23] Despite this attack, Ravel continued to admire Satie's early music, and always acknowledged the older man's influence on his own development.[56] Ravel took a benign view of Les Six, promoting their music, and defending it against journalistic attacks. He regarded their reaction against his works as natural, and preferable to their copying his style.[128] Through the Société Musicale Indépendente, he was able to encourage them and composers from other countries. The Société presented concerts of recent works by American composers including Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson and George Antheil and by Vaughan Williams and his English colleagues Arnold Bax and Cyril Scott.[129]

Orenstein and Zank both comment that, although Ravel's post-war output was small, averaging only one composition a year, it included some of his finest works.[130] In 1920 he completed La valse, in response to a commission from Diaghilev. He had worked on it intermittently for some years, planning a concert piece, "a sort of apotheosis of the Viennese waltz, mingled with, in my mind, the impression of a fantastic, fatal whirling".[131] It was rejected by Diaghilev, who said, "It's a masterpiece, but it's not a ballet. It's the portrait of a ballet."[132] Ravel heard Diaghilev's verdict without protest or argument, left, and had no further dealings with him.[133][n 24] Nichols comments that Ravel had the satisfaction of seeing the ballet staged twice by other managements before Diaghilev died.[136] A ballet danced to the orchestral version of Le tombeau de Couperin was given at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in November 1920, and the premiere of La valse followed in December.[137] The following year Daphnis et Chloé and L'heure espagnole were successfully revived at the Paris Opéra.[137]

In the post-war era there was a reaction against the large-scale music of composers such as Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss.[138] Stravinsky, whose Rite of Spring was written for a huge orchestra, began to work on a much smaller scale. His 1923 ballet score Les noces is composed for voices and twenty-one instruments.[139] Ravel did not like the work (his opinion caused a cooling in Stravinsky's friendship with him)[140] but he was in sympathy with the fashion for "dépouillement" – the "stripping away" of pre-war extravagance to reveal the essentials.[128] Many of his works from the 1920s are noticeably sparer in texture than earlier pieces.[141] Other influences on him in this period were jazz and atonality. Jazz was popular in Parisian cafés, and French composers such as Darius Milhaud incorporated elements of it in their work.[142] Ravel commented that he preferred jazz to grand opera,[143] and its influence is heard in his later music.[144] Arnold Schönberg's abandonment of conventional tonality also had echoes in some of Ravel's music such as the Chansons madécasses[n 25] (1926), which Ravel doubted he could have written without the example of Pierrot Lunaire.[145] His other major works from the 1920s include the orchestral arrangement of Mussorgsky's piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition (1922), the opera L'enfant et les sortilèges[n 26] to a libretto by Colette (1926), Tzigane (1924) and the Violin Sonata (1927).[137]

Finding city life fatiguing, Ravel moved to the countryside.[146] In May 1921 he took up residence at Le Belvédère, a small house on the fringe of Montfort-l'Amaury, 50 kilometres (31 mi) west of Paris, in the Yvelines département. Looked after by a devoted housekeeper, Mme Revelot, he lived there for the rest of his life.[147] At Le Belvédère Ravel composed and gardened, when not performing in Paris or abroad. His touring schedule increased considerably in the 1920s, with concerts in Britain, Sweden, Denmark, the US, Canada, Spain, Austria and Italy.[137]

Ravel was fascinated by the dynamism of American life, its huge cities, skyscrapers, and its advanced technology, and was impressed by its jazz, Negro spirituals, and the excellence of American orchestras. American cuisine was apparently another matter.

Arbie Orenstein[148]

After two months of planning, Ravel made a four-month tour of North America in 1928, playing and conducting. His fee was a guaranteed minimum of $10,000 and a constant supply of Gauloises cigarettes.[149] He appeared with most of the leading orchestras in Canada and the US and visited twenty-five cities.[150] Audiences were enthusiastic and the critics were complimentary.[n 27] At an all-Ravel programme conducted by Serge Koussevitzky in New York, the entire audience stood up and applauded as the composer took his seat. Ravel was touched by this spontaneous gesture and observed, "You know, this doesn't happen to me in Paris."[148] Orenstein, commenting that this tour marked the zenith of Ravel's international reputation, lists its non-musical highlights as a visit to Poe's house in New York, and excursions to Niagara Falls and the Grand Canyon.[148] Ravel was unmoved by his new international celebrity. He commented that the critics' recent enthusiasm was of no more importance than their earlier judgment, when they called him "the most perfect example of insensitivity and lack of emotion".[152]

The last composition Ravel completed in the 1920s, Boléro, became his most famous. He was commissioned to provide a score for Ida Rubinstein's ballet company, and having been unable to secure the rights to orchestrate Albéniz's Iberia, he decided on "an experiment in a very special and limited direction ... a piece lasting seventeen minutes and consisting wholly of orchestral tissue without music".[153] Ravel continued that the work was "one long, very gradual crescendo. There are no contrasts, and there is practically no invention except the plan and the manner of the execution. The themes are altogether impersonal."[153] He was astonished, and not wholly pleased, that it became a mass success. When one elderly member of the audience at the Opéra shouted "Rubbish!" at the premiere, he remarked, "That old lady got the message!"[154] The work was popularised by the conductor Arturo Toscanini,[155] and has been recorded several hundred times.[n 28] Ravel commented to Arthur Honegger, one of Les Six, "I've written only one masterpiece – Boléro. Unfortunately there's no music in it."[157]

Last years

At the beginning of the 1930s Ravel was working on two piano concertos. He completed the Piano Concerto in D major for the Left Hand first. It was commissioned by the Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who had lost his right arm during the war. Ravel was stimulated by the technical challenges of the project: "In a work of this kind, it is essential to give the impression of a texture no thinner than that of a part written for both hands."[158] Ravel, not proficient enough to perform the work with only his left hand, demonstrated it with both hands.[n 29] Wittgenstein was initially disappointed by the piece, but after long study he became fascinated by it and ranked it as a great work.[160] In January 1932 he premiered it in Vienna to instant acclaim, and performed it in Paris with Ravel conducting the following year.[161] The critic Henry Prunières wrote, "From the opening measures, we are plunged into a world in which Ravel has but rarely introduced us."[152]

The Piano Concerto in G major was completed a year later. After the premiere in January 1932 there was high praise for the soloist, Marguerite Long, and for Ravel's score, though not for his conducting.[162] Long, the dedicatee, played the concerto in more than twenty European cities, with the composer conducting;[163] they planned to record it together, but at the sessions Ravel confined himself to supervising proceedings and Pedro de Freitas Branco conducted.[164]

His final years were cruel, for he was gradually losing his memory and some of his coordinating powers, and he was, of course, quite aware of it.

Igor Stravinsky[165]

In October 1932 Ravel suffered a blow to the head in a taxi accident. The injury was not thought serious at the time, but in a study for the British Medical Journal in 1988 the neurologist R. A. Henson concludes that it may have exacerbated an existing cerebral condition.[166] As early as 1927 close friends had been concerned at Ravel's growing absent-mindedness, and within a year of the accident he started to experience symptoms suggesting aphasia.[167] Before the accident he had begun work on music for a film, Don Quixote (1933), but he was unable to meet the production schedule, and Jacques Ibert wrote most of the score.[168] Ravel completed three songs for baritone and orchestra intended for the film; they were published as Don Quichotte à Dulcinée. The manuscript orchestral score is in Ravel's hand, but Lucien Garban and Manuel Rosenthal helped in transcription. Ravel composed no more after this.[166] The exact nature of his illness is unknown. Experts have ruled out the possibility of a tumour, and have variously suggested frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer's disease and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.[169][n 30] Though no longer able to write music or perform, Ravel remained physically and socially active until his last months. Henson notes that Ravel preserved most or all his auditory imagery and could still hear music in his head.[166]

In 1937 Ravel began to suffer pain from his condition, and was examined by Clovis Vincent, a well-known Paris neurosurgeon. Vincent advised surgical treatment. He thought a tumour unlikely, and expected to find ventricular dilatation that surgery might prevent from progressing. Ravel's brother Edouard accepted this advice; as Henson comments, the patient was in no state to express a considered view. After the operation there seemed to be an improvement in his condition, but it was short-lived, and he soon lapsed into a coma. He died on 28 December, at the age of 62.[172]

On 30 December 1937 Ravel was interred next to his parents in a granite tomb at Levallois-Perret cemetery, in north-west Paris. He was an atheist and there was no religious ceremony.[173]

Music

Marcel Marnat's catalogue of Ravel's complete works lists eighty-five works, including many incomplete or abandoned.[174] Though that total is small in comparison with the output of his major contemporaries,[n 31] it is nevertheless inflated by Ravel's frequent practice of writing works for piano and later rewriting them as independent pieces for orchestra.[75] The performable body of works numbers about sixty; slightly more than half are instrumental. Ravel's music includes pieces for piano, chamber music, two piano concerti, ballet music, opera and song cycles. He wrote no symphonies or church works.[174]

Ravel drew on many generations of French composers from Couperin and Rameau to Fauré and the more recent innovations of Satie and Debussy. Foreign influences include Mozart, Schubert, Liszt and Chopin.[176] He considered himself in many ways a classicist, often using traditional structures and forms, such as the ternary, to present his new melodic and rhythmic content and innovative harmonies.[177] The influence of jazz on his later music is heard within conventional classical structures in the Piano Concerto and the Violin Sonata.[178]

Whatever sauce you put around the melody is a matter of taste. What is important is the melodic line.

Ravel to Vaughan Williams[179]

Ravel placed high importance on melody, telling Vaughan Williams that there is "an implied melodic outline in all vital music".[180] As a result, there are few leading notes in his output.[181] Chords of the ninth and eleventh and unresolved appoggiaturas, such as those in the Valses nobles et sentimentales, are characteristic of Ravel's harmonic language.[182]

Dance forms appealed to Ravel, most famously the bolero and pavane, but also the minuet, forlane, rigaudon, waltz, czardas, habanera and passacaglia. National and regional consciousness was important to him, and although a planned concerto on Basque themes never materialised, his works include allusions to Hebraic, Greek, Hungarian and gypsy themes.[183] He wrote several short pieces paying tribute to composers he admired – Borodin, Chabrier, Fauré and Haydn, interpreting their characteristics in a Ravellian style.[184] Another important influence was literary rather than musical: Ravel said that he learnt from Poe that "true art is a perfect balance between pure intellect and emotion",[185] with the corollary that a piece of music should be a perfectly balanced entity with no irrelevant material allowed to intrude.[186]

Operas

Ravel completed two operas, and worked on three others. The unrealised three were Olympia, La cloche engloutie and Jeanne d'Arc. Olympia was to be based on Hoffmann's The Sandman; he made sketches for it in 1898–99, but did not progress far. La cloche engloutie after Hauptmann's The Sunken Bell occupied him intermittently from 1906 to 1912, Ravel destroyed the sketches for both these works, except for a "Symphonie horlogère" which he incorporated into the opening of L'heure espagnole.[187] The third unrealised project was an operatic version of Joseph Delteil's 1925 novel about Joan of Arc. It was to be a large-scale, full-length work for the Paris Opéra, but Ravel's final illness prevented him from writing it.[188]

Ravel's first completed opera was L'heure espagnole (premiered in 1911), described as a "comédie musicale".[189] It is among the works set in or illustrating Spain that Ravel wrote throughout his career. Nichols comments that the essential Spanish colouring gave Ravel a reason for virtuoso use of the modern orchestra, which the composer considered "perfectly designed for underlining and exaggerating comic effects".[190] Edward Burlingame Hill found Ravel's vocal writing particularly skilful in the work, "giving the singers something besides recitative without hampering the action", and "commenting orchestrally upon the dramatic situations and the sentiments of the actors without diverting attention from the stage".[191] Some find the characters artificial and the piece lacking in humanity.[189] The critic David Murray writes that the score "glows with the famous Ravel tendresse."[192]

The second opera, also in one act, is L'enfant et les sortilèges (1926), a "fantaisie lyrique" to a libretto by Colette. She and Ravel had planned the story as a ballet, but at the composer's suggestion Colette turned it into an opera libretto. It is more uncompromisingly modern in its musical style than L'heure espagnole, and the jazz elements and bitonality of much of the work upset many Parisian opera-goers. Ravel was once again accused of artificiality and lack of human emotion, but Nichols finds "profoundly serious feeling at the heart of this vivid and entertaining work".[193] The score presents an impression of simplicity, disguising intricate links between themes, with, in Murray's phrase, "extraordinary and bewitching sounds from the orchestra pit throughout".[194]

Although one-act operas are generally staged less often than full-length ones,[195] Ravel's are produced regularly in France and abroad.[196]

Other vocal works

A substantial proportion of Ravel's output was vocal. His early works in that sphere include cantatas written for his unsuccessful attempts at the Prix de Rome. His other vocal music from that period shows Debussy's influence, in what Kelly describes as "a static, recitative-like vocal style", prominent piano parts and rhythmic flexibility.[18] By 1906 Ravel was taking even further than Debussy the natural, sometimes colloquial, setting of the French language in Histoires naturelles. The same technique is highlighted in Trois poèmes de Mallarmé (1913); Debussy set two of the three poems at the same time as Ravel, and the former's word-setting is noticeably more formal than the latter's, in which syllables are often elided. In the cycles Shéhérazade and Chansons madécasses, Ravel gives vent to his taste for the exotic, even the sensual, in both the vocal line and the accompaniment.[18][197]

Ravel's songs often draw on vernacular styles, using elements of many folk traditions in such works as Cinq mélodies populaires grecques, Deux mélodies hébraïques and Chants populaires.[198] Among the poets on whose lyrics he drew were Marot, Léon-Paul Fargue, Leconte de Lisle and Verlaine. For three songs dating from 1914 to 1915, he wrote his own texts.[199]

Although Ravel wrote for mixed choirs and male solo voices, he is chiefly associated, in his songs, with the soprano and mezzo-soprano voices. Even when setting lyrics clearly narrated by a man, he often favoured a female voice,[200] and he seems to have preferred his best-known cycle, Shéhérazade, to be sung by a woman, although a tenor voice is a permitted alternative in the score.[201]

Orchestral works

During his lifetime it was above all as a master of orchestration that Ravel was famous.[202] He minutely studied the ability of each orchestral instrument to determine its potential, putting its individual colour and timbre to maximum use.[203] The critic Alexis Roland-Manuel wrote, "In reality he is, with Stravinsky, the one man in the world who best knows the weight of a trombone-note, the harmonics of a 'cello or a pp tam-tam in the relationships of one orchestral group to another."[204]

For all Ravel's orchestral mastery, only four of his works were conceived as concert works for symphony orchestra: Rapsodie espagnole, La valse and the two concertos. All the other orchestral works were written either for the stage, as in Daphnis et Chloé, or as a reworking of piano pieces, Alborada del gracioso and Une barque sur l'ocean, (Miroirs), Valses nobles et sentimentales, Ma mère l'Oye, Tzigane (originally for violin and piano) and Le tombeau de Couperin.[205] In the orchestral versions, the instrumentation generally clarifies the harmonic language of the score and brings sharpness to classical dance rhythms.[206] Occasionally, as in the Alborada del gracioso, critics have found the later orchestral version less persuasive than the sharp-edged piano original.[207]

In some of his scores from the 1920s, including Daphnis et Chloé, Ravel frequently divides his upper strings, having them play in six to eight parts while the woodwind are required to play with extreme agility. His writing for the brass ranges from softly muted to triple-forte outbursts at climactic points.[208] In the 1930s he tended to simplify his orchestral textures. The lighter tone of the G major Piano Concerto follows the models of Mozart and Saint-Saëns, alongside use of jazz-like themes.[209] The critics Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor comment that in the slow movement, "one of the most beautiful tunes Ravel ever invented", the composer "can truly be said to join hands with Mozart".[210] The most popular of Ravel's orchestral works, Boléro (1928), was conceived several years before its completion; in 1924 he said that he was contemplating "a symphonic poem without a subject, where the whole interest will be in the rhythm".[211]

Ravel made orchestral versions of piano works by Schumann, Chabrier, Debussy and Mussorgsky's piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition. Orchestral versions of the last by Mikhail Tushmalov, Sir Henry Wood and Leo Funtek predated Ravel's 1922 version, and many more have been made since, but Ravel's remains the best known.[212] Kelly remarks on its "dazzling array of instrumental colour",[18] and a contemporary reviewer commented on how, in dealing with another composer's music, Ravel had produced an orchestral sound wholly unlike his own.[213]

Piano music

Although Ravel wrote fewer than thirty works for the piano, they exemplify his range; Orenstein remarks that the composer keeps his personal touch "from the striking simplicity of Ma mère l'Oye to the transcendental virtuosity of Gaspard de la nuit".[214] Ravel's earliest major work for piano, Jeux d'eau (1901), is frequently cited as evidence that he evolved his style independently of Debussy, whose major works for piano all came later.[215] When writing for solo piano, Ravel rarely aimed at the intimate chamber effect characteristic of Debussy, but sought a Lisztian virtuosity.[216] The authors of The Record Guide consider that works such as Gaspard de la Nuit and Miroirs have a beauty and originality with a deeper inspiration "in the harmonic and melodic genius of Ravel himself".[216]

Most of Ravel's piano music is extremely difficult to play, and presents pianists with a balance of technical and artistic challenges.[217][n 32] Writing of the piano music the critic Andrew Clark commented in 2013, "A successful Ravel interpretation is a finely balanced thing. It involves subtle musicianship, a feeling for pianistic colour and the sort of lightly worn virtuosity that masks the advanced technical challenges he makes in Alborada del gracioso ... and the two outer movements of Gaspard de la nuit. Too much temperament, and the music loses its classical shape; too little, and it sounds pale."[219] This balance caused a breach between the composer and Viñes, who said that if he observed the nuances and speeds Ravel stipulated in Gaspard de la nuit, "Le gibet" would "bore the audience to death".[220] Some pianists continue to attract criticism for over-interpreting Ravel's piano writing.[221][n 33]

Ravel's regard for his predecessors is heard in several of his piano works; Menuet sur le nom de Haydn (1909), À la manière de Borodine (1912), À la manière de Chabrier (1913) and Le tombeau de Couperin all incorporate elements of the named composers interpreted in a characteristically Ravellian manner.[223] Clark comments that those piano works which Ravel later orchestrated are overshadowed by the revised versions: "Listen to Le tombeau de Couperin and the complete ballet music for Ma mère L'Oye in the classic recordings conducted by André Cluytens, and the piano versions never sound quite the same again."[219]

Chamber music

Apart from a one-movement sonata for violin and piano dating from 1899, unpublished in the composer's lifetime, Ravel wrote seven chamber works.[18] The earliest is the String Quartet (1902–03), dedicated to Fauré, and showing the influence of Debussy's quartet of ten years earlier. Like the Debussy, it differs from the more monumental quartets of the established French school of Franck and his followers, with more succinct melodies, fluently interchanged, in flexible tempos and varieties of instrumental colour.[224] The Introduction and Allegro for harp, flute, clarinet and string quartet (1905) was composed very quickly by Ravel's standards. It is an ethereal piece in the vein of the Pavane pour une infante défunte.[225] Ravel also worked at unusual speed on the Piano Trio (1914) to complete it before joining the French Army. It contains Basque, Baroque and far Eastern influences, and shows Ravel's growing technical skill, dealing with the difficulties of balancing the percussive piano with the sustained sound of the violin and cello, "blending the two disparate elements in a musical language that is unmistakably his own," in the words of the commentator Keith Anderson.[226]

Ravel's four chamber works composed after the First World War are the Sonata for Violin and Cello (1920–22), the "Berceuse sur le nom de Gabriel Fauré" for violin and piano (1922), the chamber original of Tzigane for violin and piano (1924) and finally the Violin Sonata (1923–27).[18] The two middle works are respectively an affectionate tribute to Ravel's teacher,[227] and a virtuoso display piece for the violinist Jelly d'Arányi.[228] The Violin and Cello Sonata is a departure from the rich textures and harmonies of the pre-war Piano Trio: the composer said that it marked a turning point in his career, with thinness of texture pushed to the extreme and harmonic charm renounced in favour of pure melody.[229] His last chamber work, the Violin Sonata (sometimes called the Second after the posthumous publication of his student sonata), is a frequently dissonant work. Ravel said that the violin and piano are "essentially incompatible" instruments, and that his Sonata reveals their incompatibility.[229] Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor consider the post-war sonatas "rather laboured and unsatisfactory",[230] and neither work has matched the popularity of Ravel's pre-war chamber works.[231]

Recordings

Ravel's interpretations of some of his piano works were captured on piano roll between 1914 and 1928, although some rolls supposedly played by him may have been made under his supervision by Robert Casadesus, a better pianist.[232] Transfers of the rolls have been released on compact disc.[232] In 1913 there was a gramophone recording of Jeux d'eau played by Mark Hambourg, and by the early 1920s there were discs featuring the Pavane pour une infante défunte and Ondine, and movements from the String Quartet, Le tombeau de Couperin and Ma mère l'Oye.[233] Ravel was among the first composers who recognised the potential of recording to bring their music to a wider public,[n 34] and throughout the 1920s there was a steady stream of recordings of his works, some of which featured the composer as pianist or conductor.[235] A 1932 recording of the G major Piano Concerto was advertised as "Conducted by the composer",[236] although he had in fact supervised the sessions while a more proficient conductor took the baton.[237] Recordings for which Ravel actually was the conductor included a Boléro in 1930, and a sound film of a 1933 performance of the D major concerto with Wittgenstein as soloist.[238]

Honours and legacy

Ravel declined not only the Légion d'honneur, but all state honours from France, refusing to let his name go forward for election to the Institut de France.[239] He accepted foreign awards, including honorary membership of the Royal Philharmonic Society in 1921,[240] the Belgian Ordre de Léopold in 1926, and an honorary doctorate from the University of Oxford in 1928.[241]

After Ravel's death, his brother and legatee, Edouard, turned the composer's house at Montfort-l'Amaury into a museum, leaving it substantially as Ravel had known it. As of 2022, the maison-musée de Maurice Ravel remains open for guided tours.[242]

In his later years, Edouard Ravel declared his intention to leave the bulk of the composer's estate to the city of Paris for the endowment of a Nobel Prize in music, but evidently changed his mind.[243] After his death in 1960, the estate passed through several hands. Despite the substantial royalties paid for performing Ravel's music, the news magazine Le Point reported in 2000 that it was unclear who the beneficiaries were.[244] The British newspaper The Guardian reported in 2001 that no money from royalties had been forthcoming for the maintenance of the Ravel museum at Montfort-l'Amaury, which was in a poor state of repair.[243]

Many works were dedicated to Ravel, including:[245]

- Air Louis XIII by Balthazar de Beaujoyeulx

- Chant de joie by Arthur Honegger

- Esquisse d'Espagne by Gustave Samazeuilh

- 4 Hommages pour le piano by Ricardo Viñes

- 11 Inventions by Erwin Schulhoff

- 3 Japanese Lyrics by Stravinsky

- 9 Pezzi by Alfredo Casella

- Piano Concerto for the Left Hand No. 2 by Utsyo Chakraborty

- 3 Pieces by Arthur Honegger

- 4 Poemes hindous by Maurice Delage

- 7 Preludes by Alexandre Tansman

- 24 Preludes by Robert Casadesus

- 3 Sarabandes by Erik Satie

- String Trio by Roland-Manuel

Many works have been written in memoriam of Ravel, including:

- Elegy in Memory of Maurice Ravel by David Diamond[246]

- Waltz "In Memoriam of Maurice Ravel" (1976) by Robert Moran (also has been arranged for harp by Mario Falcao)[247]

- Sinfonia in memoriam Maurice Ravel (1940) by Rudolf Escher[248]

- Douze etudes d'interprétation: No. 4 "Main gauche seule (in memoriam Maurice Ravel)" (1983) by Maurice Ohana[249]

- Toccata and Fugue in memoriam Maurice Ravel, for organ by Josef Friedrich Doppelbauer[250]

- Déjà Vu - in memoriam Maurice Ravel by Lukáš Sommer[251]

- In Memoriam Maurice Ravel (1938) poetry and illustrations by Robert Franquinet[252]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- /rəˈvɛl, ræˈvɛl/ rə-VEL, rav-EL;[1][2][3] French: [ʒɔzɛf mɔʁis ʁavɛl]

- Joseph's family is described in some sources as French and in others as Swiss; Versoix is in present-day (2015) Switzerland, but as the historian Philippe Morant observes, the nationality of families from the area changed several times over the generations as borders were moved; Joseph held a French passport,[5] but Ravel preferred to say simply that his paternal ancestors came from the Jura.[6]

- Students who failed in three consecutive years to win a competitive medal were automatically expelled ("faute de récompense") from their course.[23][29]

- "Ballad of the queen who died of love"

- When he was a boy his mother had occasionally had to bribe him to do his piano exercises,[26] and throughout his life colleagues commented on his aversion to practice.[30]

- Respectively, "A great black sleep" and "Anne playing the spinet".

- This critic was "Willy", Henri Gauthier-Villars, who came to be an admirer of Ravel. Ravel came to share his poor view of the overture, calling it "a clumsy botch-up".[39]

- Ravel produced an orchestral version eleven years later.[23]

- Ravel was 160 centimetres (5ft 3in) tall.[47]

- Other members were the composers Florent Schmitt, Maurice Delage and Paul Ladmirault, the poets Léon-Paul Fargue and Tristan Klingsor, the painter Paul Sordes and the critic Michel Calvocoressi.[50]

- Ravel later came to the view that "Impressionism" was not a suitable term for any music, and was essentially relevant only to painting.[57]

- Literally "Games of water", sometimes translated as "Fountains"

- Ravel admitted in 1926 that he had submitted at least one piece deliberately parodying the required conventional form: the cantata Myrrha, which he wrote for the 1901 competition.[67]

- The musicologist David Lamaze has suggested that Ravel felt a long-lasting romantic attraction to Misia, and posits that her name is incorporated in Ravel's music in the recurring pattern of the notes E, B, A – "Mi, Si, La" in French solfège.[72]

- This remark was modified by Hollywood writers for the film Rhapsody in Blue in 1945, in which Ravel (played by Oscar Loraine) tells Gershwin (Robert Alda) "If you study with me you'll only write second-rate Ravel instead of first-rate Gershwin."[80]

- Ravel, known for his gourmet tastes, developed an unexpected enthusiasm for English cooking, particularly steak and kidney pudding with stout.[88]

- Fauré also retained the presidency of the rival Société Nationale, retaining the affection and respect of members of both bodies, including d'Indy.[90]

- "The Spanish Hour"

- The year in which the work was commissioned is generally thought to be 1909, although Ravel recalled it as being as early as 1907.[99]

- Ravel wrote to a friend, "I have to tell you that the last week has been insane: preparing a ballet libretto for the next Russian season. [I've been] working up to 3 a.m. almost every night. To confuse matters, Fokine does not know a word of French, and I can only curse in Russian. Irrespective of the translators, you can imagine the timbre of these conversations."[104]

- The public premiere was the scene of a near-riot, with factions of the audience for and against the work, but the music rapidly entered the repertory in the theatre and the concert hall.[109]

- He never made clear his reason for refusing it. Several theories have been put forward. Rosenthal believed that it was because so many had died in a war in which Ravel had not actually fought.[122] Another suggestion is that Ravel felt betrayed because despite his wishes his ailing mother had been told that he had joined the army.[122] Edouard Ravel said that his brother refused the award because it had been announced without the recipient's prior acceptance.[122] Many biographers believe that Ravel's experience during the Prix de Rome scandal convinced him that state institutions were inimical to progressive artists.[123]

- Satie was known for turning against friends. In 1917, using obscene language, he inveighed against Ravel to the teenaged Francis Poulenc.[125] By 1924 Satie had repudiated Poulenc and another former friend Georges Auric.[126] Poulenc told a friend that he was delighted not to see Satie any more: "I admire him as ever, but breathe a sigh of relief at finally not having to listen to his eternal ramblings on the subject of Ravel ..."[127]

- According to some sources, when Diaghilev encountered him in 1925, Ravel refused to shake his hand, and one of the two men challenged the other to a duel. Harold Schonberg names Diaghilev as the challenger, and Gerald Larner names Ravel.[134] No duel took place, and no such incident is mentioned in the biographies by Orenstein or Nichols, though both record that the breach was total and permanent.[135]

- "Madagascan Songs"

- "The Child and the Spells"

- In The New York Times Olin Downes wrote, "Mr. Ravel has pursued his way as an artist quietly and very well. He has disdained superficial or meretricious effects. He has been his own most unsparing critic."[151]

- In 2015 WorldCat listed more than 3,500 new or reissued recordings of the piece.[156]

- It was a matter for affectionate debate among Ravel's friends and colleagues whether he was worse at conducting or playing.[159]

- In 2008 The New York Times published an article suggesting that the early effects of frontotemporal dementia in 1928 might account for the repetitive nature of Boléro.[170] This followed a 2002 article in The European Journal of Neurology, examining Ravel's clinical history and arguing that Boléro and the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand both suggest the impacts of neurological disease.[171]

- Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians credits Saint-Saëns with 169 works, Fauré with 121 works and Debussy with 182.[175]

- In 2009 the pianist Steven Osborne wrote of Gaspard, "This bloody opening! I feel I've tried every possible fingering and nothing works. In desperation, I divide the notes of the first bar between my two hands rather than playing them with just one, and suddenly I see a way forward. But now I need a third hand for the melody."[218]

- In a 2001 survey of recordings of Gaspard de la nuit the critic Andrew Clements wrote, "Ivo Pogorelich ... deserves to be on that list too, but his phrasing is so indulgent that in the end it cannot be taken seriously ... Ravel's writing is so minutely calculated and carefully defined that he leaves interpreters little room for manoeuvre; Ashkenazy takes a few liberties, so too does Argerich."[221] Ravel himself admonished Marguerite Long, "You should not interpret my music: you should realise it." ("Il ne faut pas interpreter ma music, il faut le réaliser.")[222]

- Other composers who made recordings of their music during the early years of the gramophone included Elgar, Grieg, Rachmaninoff and Richard Strauss.[234]

References

- "Ravel, Maurice". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021.

- "Ravel". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- "Ravel, Maurice". Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Longman. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- Nichols (2011), p. 1

- Nichols (2011), p. 390

- Quoted in Nichols (2011), p. 3

- Nichols (2011), p. 6

- James, p. 13

- Orenstein (1991), p. 9

- Orenstein (1991), p. 8

- Howat, p. 71

- Orenstein (1995), pp. 91–92

- Orenstein (1991), p. 10

- Quoted in Goss, p. 23

- Nichols (2011), p. 9

- Goss, p. 23

- Goss, p. 24

- Kelly, Barbara L. "Ravel, Maurice", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 26 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Orenstein (1967), p. 475

- James, p. 15

- Orenstein (1991), p. 16

- Orenstein (1991), pp. 11–12; and Nichols (2011), pp. 10–11

- Lesure and Nectoux, p. 9

- Orenstein (1991), p. 11

- Nichols (2011), pp. 11 and 390

- Orenstein (1995), p. 92

- Orenstein (1991), p. 14

- Kelly (2000), p. 7

- Nichols (2011), p. 14

- Nichols (1987), pp. 73 and 91

- Jankélévitch, pp. 8 and 20

- Nichols (1987), p. 183

- Quoted in Orenstein (1991), p. 33

- Nichols (1977), pp. 14–15

- Nichols (2011), p. 35; and Orenstein (1991), p. 26

- Nichols (1987), p. 178

- Nichols (1977), p. 15

- Orenstein (1991), p. 24

- Nichols (1977), p. 12

- Nichols (2011), p. 30

- Langham Smith, Richard. "Maurice Ravel – Biography" Archived 11 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, retrieved 4 March 2014

- Larner, pp. 59–60

- Nichols (1987), pp. 118 and 184

- Orenstein (1991), pp. 19 and 104

- James, p. 22

- Nichols (1987), pp. 10–14

- Orenstein (1991), p. 111

- Nichols, pp. 57 and 106; and Lesure and Nectoux, pp. 15, 16 and 28

- Orenstein (1991), p. 28

- Pasler, p. 403; Nichols (1977), p. 20; and Orenstein (1991), p. 28

- Nichols (1987), p. 101

- Orledge, p. 65 (Dubois); and Donnellon, pp. 8–9 (Saint-Saëns)

- McAuliffe, pp. 57–58

- McAuliffe, p. 58

- James, pp. 30–31

- Kelly (2000), p. 16

- Orenstein (2003), p. 421

- Orenstein (1991), p. 127

- Orenstein (1991), p. 33; and James, p. 20

- Landormy, p. 431

- Nichols (2011), p. 52

- James, p. 46

- Nichols (1987), p. 102

- Nichols (2011), pp. 58–59

- "Winners of the Prix de Rome", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 27 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Macdonald, p. 332

- Macdonald, p. 332; and Kelly, p. 8

- Hill, p. 134; and Duchen, pp. 149–150

- Nichols (1977), p. 32

- Woldu, pp. 247 and 249

- Nectoux, p. 267

- "Hidden clue to composer's passion" Archived 30 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 27 March 2009

- Nichols (2011), pp. 66–67

- Goddard, p. 292

- Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 607

- Nichols (1987), p. 32

- Nichols (2011), pp. 26–30; and Pollack, pp. 119–120

- Quoted in Nichols (1987), p. 67

- Pollack, p. 119

- Pollack, p. 728

- Vaughan Williams, p. 79

- Nichols (1987), pp. 70 (Vaughan Williams), 36 (Rosenthal) and 32 (Long)

- Nichols (1987), p. 35

- Nichols (1987), pp. 35–36

- Ivry, p. 4

- Whitesell, p. 78; and Nichols (2011), p. 350

- "Société des Concerts Français", The Times, 27 April 1909, p. 8; and Nichols (2011), pp. 108–109

- Nichols (2011), p. 109

- Strasser, p. 251

- Jones, p. 133

- "Courrier Musicale", Le Figaro, 20 April 1910, p. 6

- Kilpatrick, pp. 103–104, and 106

- Kilpatrick, p. 132

- Orenstein (1991), p. 65

- Quoted in Zank, p. 259

- "Promenade Concerts", The Times, 28 August 1912, p. 7

- "New York Symphony in New Aeolian Hall", The New York Times, 9 November 1912 (subscription required) Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Morrison, pp. 63–64; and Nichols (2011), p. 141

- Morrison, pp. 57–58

- Morrison, p. 54

- Nichols (1987), pp. 41–43

- Morrison, p. 50

- Orenstein (1991), p. 60; and "Return of the Russian Ballet", The Times, 10 June 1914, p. 11

- Quoted in Morrison, p. 54

- James, p. 72

- Canarina, p. 43

- Nichols (1987), p. 113

- Nichols (2011), p. 157

- Canarina, pp. 42 and 47

- Jankélévitch, p. 179

- Nichols (2011), p. 179

- Orenstein (1995), p. 93

- Quoted in Nichols (1987), p. 113

- Larner, p. 158

- Fulcher (2001), pp. 207–208

- Orenstein (2003), p. 169

- Fulcher (2001), p. 208

- Orenstein (2003), p. 180; and Nichols (2011), p. 187

- James, p. 81

- Zank, p. 11

- Orenstein (2003), pp. 230–231

- Fulcher (2005), p. 139

- Kelly (2000), p. 9; Macdonald, p. 333; and Zank, p. 10

- Kelly (2013), p. 56

- Poulenc and Audel, p. 175

- Schmidt. p. 136

- Kelly (2013), p. 57

- Kelly (2000), p. 25

- Orenstein (1991), pp. 82–83

- Orenstein (1967), p. 479; and Zank, p. 11

- Quoted in Orenstein (2003), p. 32

- Nichols (1987), p. 118

- Orenstein (1991), p. 78

- Schonberg, p. 468; and Larner, p. 188

- Orenstein (1991), p. 78; and Nichols (2011), p. 210

- Nichols (2011), p. 210

- Lesure and Nectoux, p. 10

- Orenstein (1991), p. 84

- "Noces, Les" Archived 16 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Oxford Companion to Music, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 11 March 2015 (subscription required).

- Francis Poulenc, quoted in Nichols (1987), p. 117

- Orenstein (1991), pp. 84, 186 and 197

- James, p. 101

- Nichols (2011), p. 289

- Perret, p. 347

- Kelly (2000), p. 24

- Lesure and Nectoux, p. 45

- Nichols (1987), p. 134; and "La maison-musée de Maurice Ravel", Ville Montfort-l'Amaury, retrieved 11 March 2015

- Orenstein (2003), p. 10

- Zank, p. 33

- Orenstein (1991), p. 95

- Downes, Olin. "Music: Ravel in American Debut", The New York Times, 16 January 1928, p. 25 (subscription required)

- Orenstein (1991), p. 104

- Quoted in Orenstein (2003), p. 477

- Nichols (1987), pp. 47–48

- Orenstein (1991), p. 99; and Nichols (2011), pp. 300–301

- "Ravel Bolero" Archived 26 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat, retrieved 21 April 2015

- Nichols (2011), p. 301

- James, p. 126

- Nichols (1987), p. 92

- Orenstein (1991), p 101

- Nichols and Mawer, p. 256

- Nichols and Mawer, p. 266

- Zank, p. 20

- Orenstein (2003), pp. 535–536

- Quoted in Nichols (1987), p. 173

- Henson, p. 1586

- Orenstein (1991), p. 105

- Nichols (2011), p. 330

- Henson, pp. 1586–1588

- Blakeslee, Sandra. "A Disease That Allowed Torrents of Creativity" Archived 22 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 8 April 2008

- Amaducci et al, p. 75

- Henson, p. 1588

- "Ravel and religion" Archived 5 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Maurice Ravel, retrieved 11 March 2015

- Marnat, pp. 721–784

- Nectoux Jean-Michel. "Fauré, Gabriel Archived 30 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine"; Ratner, Sabina Teller, et al. "Saint-Saëns, Camille"; and Lesure, François and Roy Howat. "Debussy, Claude", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 13 March 2015 (subscription required)

- Orenstein (1991), pp. 64 (Satie), 123 (Mozart and Schubert), 124 (Chopin and Liszt), 136 (Russians), 155 (Debussy) and 218 (Couperin and Rameau)

- Orenstein (1991), p. 135

- Nichols (2011), pp. 291, 314 and 319

- Quoted in Orenstein (1991), p. 131

- Orenstein (1991), p. 131

- Taruskin, p. 112; and "Leading note", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 13 March 2015 (subscription required)

- Orenstein (1991), p. 132

- Orenstein (1991), pp. 190 and 193

- Orenstein (1991), p. 192

- Lanford, pp. 245–246

- Lanford, pp. 248–249.

- Zank, pp. 105 and 367

- Nichols (1987), pp. 171–172

- Nichols, Roger. "Heure espagnole, L'" Archived 16 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 14 March 2015 (subscription required)

- Nichols (2011), p. 129

- Hill, p. 144

- Murray, p. 316

- Nichols, Roger. "Enfant et les sortilèges, L'" Archived 16 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 14 March 2015 (subscription required)

- Murray, p. 317

- White, p. 306

- "Maurice Ravel", Operabase, performances since 2013.

- Orenstein (1991), p. 157

- Jankélévitch, pp. 29–32

- Jankélévitch, p. 177

- Nichols (2011), p. 280

- Nichols (2011), p. 55

- Goddard, p. 291

- James, p. 21

- Quoted in Goddard, p. 292

- Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, pp. 611–612; and Goddard, p. 292

- Goddard, pp. 293–294

- Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 611

- Goddard, pp. 298–301

- Orenstein (1991), pp. 204–205

- Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 610

- Nichols (2011), p. 302

- Oldani, Robert W. "Musorgsky, Modest Petrovich", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 16 March 2015 (subscription required)

- Nichols (2011), p. 248

- Orenstein (1991), p. 193

- Orenstein (1981), p. 32; and Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 613

- Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 613

- Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, pp. 613–614

- Osborne, Steven. "Wrestling with Ravel : How do you get your fingers – and brain – round one of the most difficult pieces in the piano repertoire?", The Guardian, 30 September 2011

- Clark, Andrew. "All the best: Ravel's piano music" Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Financial Times, 16 January 2013

- Nichols (2011), p. 102

- Clements, Andrew. "Ravel: Gaspard de la Nuit" Archived 17 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 26 October 2001

- Schuller, pp. 7–8

- Orenstein (1991), p. 181

- Griffiths, Paul. "String quartet", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 31 March 2015 (subscription required)

- Anderson (1989), p. 4

- Anderson (1994), p. 5

- Phillips, p. 163

- Orenstein (1991), p. 88

- Orenstein (2003), p. 32

- Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 612

- De Voto, p. 113

- Orenstein (2003) pp. 532–533

- "Ravel" Archived 16 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Discography search, AHRC Research Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music, retrieved 15 March 2015

- Kennedy, Michael (ed). "Gramophone (Phonograph) Recordings", The Oxford Dictionary of Music, Oxford University Press, retrieved 6 April 2015 (subscription required)

- The Gramophone, Volume I, pp. 60, 183, 159 and 219; and Orenstein (2003), pp. 534–535

- Columbia advertisement,The Gramophone, Volume 10, p. xv

- Orenstein (2003), p. 536

- Orenstein (2003), pp. 534–537

- Nichols (2011), pp. 206–207

- "Honorary Members since 1826" Archived 14 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Royal Philharmonic Society, retrieved 7 April 2015

- Orenstein (1991), pp. 92 and 99

- "Maurice Ravel’s museum house", Montfort l’Amaury, retrieved 7 April 2022

- Henley, Jon. "Poor Ravel" Archived 3 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 25 April 2001

- Inchauspé, Irene. (In French) "A qui profite le Boléro de Ravel?" Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Le Point, 14 July 2000

- "Category:Ravel, Maurice - IMSLP: Free Sheet Music PDF Download". imslp.org. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- "David Diamond Papers, Music Division, Library of Congress" (PDF). Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- "American Harp Society Tape Library" (PDF). Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- "Donemus Webshop — Largo from the Sinfonia in memoriam Maurice Ravel". webshop.donemus.com. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- "Ohana, Maurice: 12 Etudes d'interpretation Vol.1 (piano)". Presto Music. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- "Doppelbauer, Josef Friedrich - Toccata und Fuge - organ". www.boosey.com. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- Lukáš Sommer: Déjà vu - in memoriam Maurice Ravel, retrieved 19 October 2022

- Franquinet, Robert (1938). In Memoriam Maurice Ravel. Maastricht: Stols. OCLC 236091095.

Sources

- Amaducci, L; E Grassi; F Boller (January 2002). "Maurice Ravel and right-hemisphere musical creativity: influence of disease on his last musical works?". European Journal of Neurology. 9 (1): 75–82. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00351.x. PMID 11784380.

- Anderson, Keith (1989). Notes to Naxos CD Debussy and Ravel String Quartets. Munich: Naxos. OCLC 884172234.

- Anderson, Keith (1994). Notes to Naxos CD French Piano Trios. Munich: Naxos. OCLC 811255627.

- Canarina, John (2003). Pierre Monteux, Maître. Pompton Plains, US: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57467-082-0.

- De Voto, Mark (2000). "Harmony in the chamber music". In Deborah Mawer (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ravel. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64856-1.

- Donnellon, Deirdre (2003). "French Music since Berlioz: Issues and Debates". In Richard Langham Smith; Caroline Potter (eds.). French Music since Berlioz. Aldershot, UK and Burlington, US: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-0282-8.

- Duchen, Jessica (2000). Gabriel Fauré. London: Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-3932-5.

- Fulcher, Jane F (2001). "Speaking the Truth to Power: The Dialogic Element in Debussy's Wartime Compositions". In Jane F Fulcher (ed.). Debussy and his World. Princeton, US: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09041-2.

- Fulcher, Jane F (2005). The Composer as Intellectual: Music and Ideology in France 1914–1940. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534296-3.

- Goddard, Scott (October 1925). "Maurice Ravel: Some Notes on His Orchestral Method". Music and Letters. 6 (4): 291–303. doi:10.1093/ml/6.4.291. JSTOR 725957.

- Goss, Madeleine (1940). Bolero: The Life of Maurice Ravel. New York: Holt. OCLC 2793964.

- Henson, R A (4 June 1988). "Maurice Ravel's Illness: A Tragedy of Lost Creativity". British Medical Journal. 296 (6636): 1585–1588. doi:10.1136/bmj.296.6636.1585. JSTOR 29530952. PMC 2545963. PMID 3135020.

- Hill, Edward Burlingame (January 1927). "Maurice Ravel". The Musical Quarterly. 13: 130–146. doi:10.1093/mq/xiii.1.130. JSTOR 738561.

- Howat, Roy (2000). "Ravel and the piano". In Deborah Mawer (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ravel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64856-1.

- Ivry, Benjamin (2000). Maurice Ravel: A Life. New York: Welcome Rain. ISBN 978-1-56649-152-5.

- James, Burnett (1987). Ravel. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-0987-8.

- Jankélévitch, Vladimir (1959) [1939]. Ravel. Margaret Crosland (trans). New York and London: Grove Press and John Calder. OCLC 474667514.

- Jones, J Barrie (1989). Gabriel Fauré: A Life in Letters. London: B T Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-5468-0.

- Kelly, Barbara L (2000). "History and Homage". In Deborah Mawer (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ravel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64856-1.

- Kelly, Barbara L (2013). Music and Ultra-modernism In France: A Fragile Consensus, 1913–1939. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-810-4.

- Kilpatrick, Emily (2009). "The Carbonne Copy: Tracing the première of L'Heure espagnole". Revue de Musicologie: 97–135. JSTOR 40648547.

- Landormy, Paul (October 1939). "Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)". The Musical Quarterly. 25 (4): 430–441. doi:10.1093/mq/xxv.4.430. JSTOR 738857.

- Lanford, Michael (September 2011). "Ravel and The Raven: The Realisation of an Inherited Aesthetic in Boléro". Cambridge Quarterly. 40 (3): 243–265. doi:10.1093/camqtly/bfr022.

- Larner, Gerald (1996). Maurice Ravel. London: Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-3270-8.

- Lesure, François; Jean-Michel Nectoux (1975). Maurice Ravel: Exposition (in French). Paris: Bibliothèque nationale. ISBN 978-2-7177-1234-6. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Macdonald, Hugh (April 1975). "Ravel and the Prix de Rome". The Musical Times. 116 (1586): 332–333. doi:10.2307/960328. JSTOR 960328.

- Marnat, Marcel (1986). "Catalogue chronologique de tous les travaux musicaux ébauchés ou terminés par Ravel". Maurice Ravel (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-01685-6.

- McAuliffe, Mary (2014). Twilight of the Belle Epoque. Lanham, US: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-2163-5.

- Morrison, Simon (Summer 2004). "The Origins of Daphnis et Chloé (1912)". 19th-Century Music. 28: 50–76. doi:10.1525/ncm.2004.28.1.50. ISSN 0148-2076. JSTOR 10.1525/ncm.2004.28.1.50.

- Murray, David (1997) [1993]. "Maurice Ravel". In Amanda Holden (ed.). The Penguin Opera Guide. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-051385-1.

- Nectoux, Jean-Michel (1991). Gabriel Fauré – A Musical Life. Roger Nichols (trans). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23524-2.

- Nichols, Roger (1977). Ravel. Master Musicians. London: Dent. ISBN 978-0-460-03146-2.

- Nichols, Roger (1987). Ravel Remembered. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-14986-5.