Mayan languages

The Mayan languages[notes 1] form a language family spoken in Mesoamerica, both in the south of Mexico and northern Central America. Mayan languages are spoken by at least 6 million Maya people, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize, El Salvador and Honduras. In 1996, Guatemala formally recognized 21 Mayan languages by name,[1][notes 2] and Mexico recognizes eight within its territory.

| Mayan | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Mesoamerica: Southern Mexico; Guatemala; Belize; western Honduras and El Salvador; small refugee and emigrant populations, especially in the United States and Canada |

Native speakers | 6.0 million |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Mayan |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | myn |

| Glottolog | maya1287 |

Location of Mayan speaking populations. See below for a detailed map of the different languages. | |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Maya civilization |

|---|

|

|

| History |

| Preclassic Maya |

| Classic Maya collapse |

| Spanish conquest of the Maya |

|

|

|

The Mayan language family is one of the best-documented and most studied in the Americas.[2] Modern Mayan languages descend from the Proto-Mayan language, thought to have been spoken at least 5,000 years ago; it has been partially reconstructed using the comparative method. The proto-Mayan language diversified into at least six different branches: the Huastecan, Quichean, Yucatecan, Qanjobalan, Mamean and Chʼolan–Tzeltalan branches.

Mayan languages form part of the Mesoamerican language area, an area of linguistic convergence developed throughout millennia of interaction between the peoples of Mesoamerica. All Mayan languages display the basic diagnostic traits of this linguistic area. For example, all use relational nouns instead of prepositions to indicate spatial relationships. They also possess grammatical and typological features that set them apart from other languages of Mesoamerica, such as the use of ergativity in the grammatical treatment of verbs and their subjects and objects, specific inflectional categories on verbs, and a special word class of "positionals" which is typical of all Mayan languages.

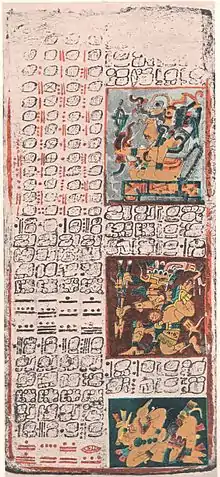

During the pre-Columbian era of Mesoamerican history, some Mayan languages were written in the logo-syllabic Maya script. Its use was particularly widespread during the Classic period of Maya civilization (c. 250–900). The surviving corpus of over 5,000 known individual Maya inscriptions on buildings, monuments, pottery and bark-paper codices,[3] combined with the rich post-Conquest literature in Mayan languages written in the Latin script, provides a basis for the modern understanding of pre-Columbian history unparalleled in the Americas.

History

Proto-Mayan

Mayan languages are the descendants of a proto-language called Proto-Mayan or, in Kʼicheʼ Maya, Nabʼee Mayaʼ Tzij ("the old Maya Language").[4] The Proto-Mayan language is believed to have been spoken in the Cuchumatanes highlands of central Guatemala in an area corresponding roughly to where Qʼanjobalan is spoken today.[5] The earliest proposal which identified the Chiapas-Guatemalan highlands as the likely "cradle" of Mayan languages was published by the German antiquarian and scholar Karl Sapper in 1912.[notes 4] Terrence Kaufman and John Justeson have reconstructed more than 3000 lexical items for the proto-Mayan language.[6]

According to the prevailing classification scheme by Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman, the first division occurred around 2200 BCE, when Huastecan split away from Mayan proper after its speakers moved northwest along the Gulf Coast of Mexico.[7] Proto-Yucatecan and Proto-Chʼolan speakers subsequently split off from the main group and moved north into the Yucatán Peninsula. Speakers of the western branch moved south into the areas now inhabited by Mamean and Quichean people. When speakers of proto-Tzeltalan later separated from the Chʼolan group and moved south into the Chiapas Highlands, they came into contact with speakers of Mixe–Zoque languages.[8] According to an alternative theory by Robertson and Houston, Huastecan stayed in the Guatemalan highlands with speakers of Chʼolan–Tzeltalan, separating from that branch at a much later date than proposed by Kaufman.[9]

In the Archaic period (before 2000 BCE), a number of loanwords from Mixe–Zoquean languages seem to have entered the proto-Mayan language. This has led to hypotheses that the early Maya were dominated by speakers of Mixe–Zoquean languages, possibly the Olmec.[notes 5] In the case of the Xincan and Lencan languages, on the other hand, Mayan languages are more often the source than the receiver of loanwords. Mayan language specialists such as Campbell believe this suggests a period of intense contact between Maya and the Lencan and Xinca people, possibly during the Classic period (250–900).[2]

Classic period

During the Classic period the major branches began diversifying into separate languages. The split between Proto-Yucatecan (in the north, that is, the Yucatán Peninsula) and Proto-Chʼolan (in the south, that is, the Chiapas highlands and Petén Basin) had already occurred by the Classic period, when most extant Maya inscriptions were written. Both variants are attested in hieroglyphic inscriptions at the Maya sites of the time, and both are commonly referred to as "Classic Maya language". Although a single prestige language was by far the most frequently recorded on extant hieroglyphic texts, evidence for at least three different varieties of Mayan have been discovered within the hieroglyphic corpus—an Eastern Chʼolan variety found in texts written in the southern Maya area and the highlands, a Western Chʼolan variety diffused from the Usumacinta region from the mid-7th century on,[10] and a Yucatecan variety found in the texts from the Yucatán Peninsula.[11] The reason why only few linguistic varieties are found in the glyphic texts is probably that these served as prestige dialects throughout the Maya region; hieroglyphic texts would have been composed in the language of the elite.[11]

Stephen Houston, John Robertson and David Stuart have suggested that the specific variety of Chʼolan found in the majority of Southern Lowland glyphic texts was a language they dub "Classic Chʼoltiʼan", the ancestor language of the modern Chʼortiʼ and Chʼoltiʼ languages. They propose that it originated in western and south-central Petén Basin, and that it was used in the inscriptions and perhaps also spoken by elites and priests.[12] However, Mora-Marín has argued that traits shared by Classic Lowland Maya and the Chʼoltiʼan languages are retentions rather than innovations, and that the diversification of Chʼolan in fact post-dates the classic period. The language of the classical lowland inscriptions then would have been proto-Chʼolan.[13]

Colonial period

During the Spanish colonization of Central America, all indigenous languages were eclipsed by Spanish, which became the new prestige language. The use of Mayan languages in many important domains of society, including administration, religion and literature, came to an end. Yet the Maya area was more resistant to outside influence than others,[notes 6] and perhaps for this reason, many Maya communities still retain a high proportion of monolingual speakers. The Maya area is now dominated by the Spanish language. While a number of Mayan languages are moribund or are considered endangered, others remain quite viable, with speakers across all age groups and native language use in all domains of society.[notes 7]

Modern period

As Maya archaeology advanced during the 20th century and nationalist and ethnic-pride-based ideologies spread, the Mayan-speaking peoples began to develop a shared ethnic identity as Maya, the heirs of the Maya civilization.[notes 8]

The word "Maya" was likely derived from the postclassical Yucatán city of Mayapan; its more restricted meaning in pre-colonial and colonial times points to an origin in a particular region of the Yucatán Peninsula. The broader meaning of "Maya" now current, while defined by linguistic relationships, is also used to refer to ethnic or cultural traits. Most Maya identify first and foremost with a particular ethnic group, e.g. as "Yucatec" or "Kʼicheʼ"; but they also recognize a shared Maya kinship.[14] Language has been fundamental in defining the boundaries of that kinship. Fabri writes: "The term Maya is problematic because Maya peoples do not constitute a homogeneous identity. Maya, rather, has become a strategy of self-representation for the Maya movements and its followers. The Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (ALMG) finds twenty-one distinct Mayan languages."[15] This pride in unity has led to an insistence on the distinctions of different Mayan languages, some of which are so closely related that they could easily be referred to as dialects of a single language. But, given that the term "dialect" has been used by some with racialist overtones in the past, as scholars made a spurious distinction between Amerindian "dialects" and European "languages", the preferred usage in Mesoamerica in recent years has been to designate the linguistic varieties spoken by different ethnic group as separate languages.[notes 9]

In Guatemala, matters such as developing standardized orthographies for the Mayan languages are governed by the Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (ALMG; Guatemalan Academy of Mayan Languages), which was founded by Maya organisations in 1986. Following the 1996 peace accords, it has been gaining a growing recognition as the regulatory authority on Mayan languages both among Mayan scholars and the Maya peoples.[16][17]

Genealogy and classification

Relations with other families

The Mayan language family has no demonstrated genetic relationship to other language families. Similarities with some languages of Mesoamerica are understood to be due to diffusion of linguistic traits from neighboring languages into Mayan and not to common ancestry. Mesoamerica has been proven to be an area of substantial linguistic diffusion.[18]

A wide range of proposals have tried to link the Mayan family to other language families or isolates, but none is generally supported by linguists. Examples include linking Mayan with the Uru–Chipaya languages, Mapuche, the Lencan languages, Purépecha, and Huave. Mayan has also been included in various Hokan, Penutian, and Siouan hypotheses. The linguist Joseph Greenberg included Mayan in his highly controversial Amerind hypothesis, which is rejected by most historical linguists as unsupported by available evidence.[19]

Writing in 1997, Lyle Campbell, an expert in Mayan languages and historical linguistics, argued that the most promising proposal is the "Macro-Mayan" hypothesis, which posits links between Mayan, the Mixe–Zoque languages and the Totonacan languages, but more research is needed to support or disprove this hypothesis.[2] In 2015, Campbell noted that recent evidence presented by David Mora-Marin makes the case for a relationship between Mayan and Mixe-Zoquean languages "much more plausible".[20][21]

Subdivisions

The Mayan family consists of thirty languages. Typically, these languages are grouped into 5-6 major subgroups (Yucatecan, Huastecan, Chʼolan–Tzeltalan, Qʼanjobʼalan, Mamean, and Kʼichean).[7][22][23] The Mayan language family is extremely well documented, and its internal genealogical classification scheme is widely accepted and established, except for some minor unresolved differences.[24]

One point still at issue is the position of Chʼolan and Qʼanjobalan–Chujean. Some scholars think these form a separate Western branch[7] (as in the diagram below). Other linguists do not support the positing of an especially close relationship between Chʼolan and Qʼanjobalan–Chujean; consequently they classify these as two distinct branches emanating directly from the proto-language.[25] An alternative proposed classification groups the Huastecan branch as springing from the Chʼolan–Tzeltalan node, rather than as an outlying branch springing directly from the proto-Mayan node.[9][12]

Distribution

Studies estimate that Mayan languages are spoken by more than 6 million people. Most of them live in Guatemala where depending on estimates 40%-60% of the population speaks a Mayan language. In Mexico the Mayan speaking population was estimated at 2.5 million people in 2010, whereas the Belizean speaker population figures around 30,000.[23]

Western branch

The Chʼolan languages were formerly widespread throughout the Maya area, but today the language with most speakers is Chʼol, spoken by 130,000 in Chiapas.[26] Its closest relative, the Chontal Maya language,[notes 10] is spoken by 55,000[27] in the state of Tabasco. Another related language, now endangered, is Chʼortiʼ, which is spoken by 30,000 in Guatemala.[28] It was previously also spoken in the extreme west of Honduras and El Salvador, but the Salvadorian variant is now extinct and the Honduran one is considered moribund. Chʼoltiʼ, a sister language of Chʼortiʼ, is also extinct.[7] Chʼolan languages are believed to be the most conservative in vocabulary and phonology, and are closely related to the language of the Classic-era inscriptions found in the Central Lowlands. They may have served as prestige languages, coexisting with other dialects in some areas. This assumption provides a plausible explanation for the geographical distance between the Chʼortiʼ zone and the areas where Chʼol and Chontal are spoken.[29]

The closest relatives of the Chʼolan languages are the languages of the Tzeltalan branch, Tzotzil and Tzeltal, both spoken in Chiapas by large and stable or growing populations (265,000 for Tzotzil and 215,000 for Tzeltal).[30] Tzeltal has tens of thousands of monolingual speakers.[31]

Qʼanjobʼal is spoken by 77,700 in Guatemala's Huehuetenango department,[32] with small populations elsewhere. The region of Qʼanjobalan speakers in Guatemala, due to genocidal policies during the Civil War and its close proximity to the Mexican border, was the source of a number of refugees. Thus there are now small Qʼanjobʼal, Jakaltek, and Akatek populations in various locations in Mexico, the United States (such as Tuscarawas County, Ohio[33] and Los Angeles, California[34]), and, through postwar resettlement, other parts of Guatemala.[35] Jakaltek (also known as Poptiʼ[36]) is spoken by almost 100,000 in several municipalities[37] of Huehuetenango. Another member of this branch is Akatek, with over 50,000 speakers in San Miguel Acatán and San Rafael La Independencia.[38]

Chuj is spoken by 40,000 people in Huehuetenango, and by 9,500 people, primarily refugees, over the border in Mexico, in the municipality of La Trinitaria, Chiapas, and the villages of Tziscau and Cuauhtémoc. Tojolabʼal is spoken in eastern Chiapas by 36,000 people.[39]

Eastern branch

The Quichean–Mamean languages and dialects, with two sub-branches and three subfamilies, are spoken in the Guatemalan highlands.

Qʼeqchiʼ (sometimes spelled Kekchi), which constitutes its own sub-branch within Quichean–Mamean, is spoken by about 800,000 people in the southern Petén, Izabal and Alta Verapaz departments of Guatemala, and also in Belize by 9,000 speakers. In El Salvador it is spoken by 12,000 as a result of recent migrations.[40]

The Uspantek language, which also springs directly from the Quichean–Mamean node, is native only to the Uspantán municipio in the department of El Quiché, and has 3,000 speakers.[41]

Within the Quichean sub-branch Kʼicheʼ (Quiché), the Mayan language with the largest number of speakers, is spoken by around 1,000,000 Kʼicheʼ Maya in the Guatemalan highlands, around the towns of Chichicastenango and Quetzaltenango and in the Cuchumatán mountains, as well as by urban emigrants in Guatemala City.[32] The famous Maya mythological document, Popol Vuh, is written in an antiquated Kʼicheʼ often called Classical Kʼicheʼ (or Quiché). The Kʼicheʼ culture was at its pinnacle at the time of the Spanish conquest. Qʼumarkaj, near the present-day city of Santa Cruz del Quiché, was its economic and ceremonial center.[42] Achi is spoken by 85,000 people in Cubulco and Rabinal, two municipios of Baja Verapaz. In some classifications, e.g. the one by Campbell, Achi is counted as a form of Kʼicheʼ. However, owing to a historical division between the two ethnic groups, the Achi Maya do not regard themselves as Kʼicheʼ.[notes 11] The Kaqchikel language is spoken by about 400,000 people in an area stretching from Guatemala City westward to the northern shore of Lake Atitlán.[43] Tzʼutujil has about 90,000 speakers in the vicinity of Lake Atitlán.[44] Other members of the Kʼichean branch are Sakapultek, spoken by about 15,000 people mostly in El Quiché department,[45] and Sipakapense, which is spoken by 8,000 people in Sipacapa, San Marcos.[46]

The largest language in the Mamean sub-branch is Mam, spoken by 478,000 people in the departments of San Marcos and Huehuetenango. Awakatek is the language of 20,000 inhabitants of central Aguacatán, another municipality of Huehuetenango. Ixil (possibly three different languages) is spoken by 70,000 in the "Ixil Triangle" region of the department of El Quiché.[47] Tektitek (or Teko) is spoken by over 6,000 people in the municipality of Tectitán, and 1,000 refugees in Mexico. According to the Ethnologue the number of speakers of Tektitek is growing.[48]

The Poqom languages are closely related to Core Quichean, with which they constitute a Poqom-Kʼichean sub-branch on the Quichean–Mamean node.[49] Poqomchiʼ is spoken by 90,000 people[50] in Purulhá, Baja Verapaz, and in the following municipalities of Alta Verapaz: Santa Cruz Verapaz, San Cristóbal Verapaz, Tactic, Tamahú and Tucurú. Poqomam is spoken by around 49,000 people in several small pockets in Guatemala.[51]

Yucatecan branch

Yucatec Maya (known simply as "Maya" to its speakers) is the most commonly spoken Mayan language in Mexico. It is currently spoken by approximately 800,000 people, the vast majority of whom are to be found on the Yucatán Peninsula.[32][52] It remains common in Yucatán and in the adjacent states of Quintana Roo and Campeche.[53]

The other three Yucatecan languages are Mopan, spoken by around 10,000 speakers primarily in Belize; Itzaʼ, an extinct or moribund language from Guatemala's Petén Basin;[54] and Lacandón or Lakantum, also severely endangered with about 1,000 speakers in a few villages on the outskirts of the Selva Lacandona, in Chiapas.[55]

Huastecan branch

Wastek (also spelled Huastec and Huaxtec) is spoken in the Mexican states of Veracruz and San Luis Potosí by around 110,000 people.[56] It is the most divergent of modern Mayan languages. Chicomuceltec was a language related to Wastek and spoken in Chiapas that became extinct some time before 1982.[57]

Phonology

Proto-Mayan sound system

Proto-Mayan (the common ancestor of the Mayan languages as reconstructed using the comparative method) has a predominant CVC syllable structure, only allowing consonant clusters across syllable boundaries.[7][22][notes 12] Most Proto-Mayan roots were monosyllabic except for a few disyllabic nominal roots. Due to subsequent vowel loss many Mayan languages now show complex consonant clusters at both ends of syllables. Following the reconstruction of Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman, the Proto-Mayan language had the following sounds.[22] It has been suggested that proto-Mayan was a tonal language, based on the fact that four different contemporary Mayan languages have tone (Yucatec, Uspantek, San Bartolo Tzotzil[notes 13] and Mochoʼ), but since these languages each can be shown to have innovated tone in different ways, Campbell considers this unlikely.[22]

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | Short | Long | Short | Long | |

| High | i | iː | u | uː | ||

| Mid | e | eː | o | oː | ||

| Low | a | aː | ||||

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Plosive | Plain | p | t | tʲ | k | q | ʔ |

| Glottalic | ɓ | tʼ | tʲʼ | kʼ | qʼ | ||

| Affricate | Plain | t͡s | t͡ʃ | ||||

| Glottalic | t͡sʼ | t͡ʃʼ | |||||

| Fricative | s | ʃ | x | h | |||

| Liquid | l r | ||||||

| Glide | j | w | |||||

Phonological evolution of Proto-Mayan

The classification of Mayan languages is based on changes shared between groups of languages. For example, languages of the western group (such as Huastecan, Yucatecan and Chʼolan) all changed the Proto-Mayan phoneme */r/ into [j], some languages of the eastern branch retained [r] (Kʼichean), and others changed it into [tʃ] or, word-finally, [t] (Mamean). The shared innovations between Huastecan, Yucatecan and Chʼolan show that they separated from the other Mayan languages before the changes found in other branches had taken place.[58]

| Proto-Mayan | Wastek | Yucatec | Mopan | Tzeltal | Chuj | Qʼanjobʼal | Mam | Ixil | Kʼicheʼ | Kaqchikel | Poqomam | Qʼeqchiʼ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *[raʔʃ] "green" |

[jaʃ] | [jaʔʃ] | [jaʔaʃ] | [jaʃ] | [jaʔaʃ] | [jaʃ] | [tʃaʃ] | [tʃaʔʃ] | [raʃ] | [rɐʃ] | [raʃ] | [raʃ] |

| *[war] "sleep" |

[waj] | [waj] | [wɐjn] | [waj] | [waj] | [waj] | [wit] (Awakatek) |

[wat] | [war] | [war] | [wɨr] | [war] |

The palatalized plosives [tʲʼ] and [tʲ] are not found in most of the modern families. Instead they are reflected differently in different branches, allowing a reconstruction of these phonemes as palatalized plosives. In the eastern branch (Chujean-Qʼanjobalan and Chʼolan) they are reflected as [t] and [tʼ]. In Mamean they are reflected as [ts] and [tsʼ] and in Quichean as [tʃ] and [tʃʼ]. Yucatec stands out from other western languages in that its palatalized plosives are sometimes changed into [tʃ] and sometimes [t].[59]

| Proto-Mayan | Yucatec | Ch'ol | Chʼortiʼ | Chuj | Qʼanjobʼal | Poptiʼ (Jakaltek) | Mam | Ixil | Kʼicheʼ | Kaqchikel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *[tʲeːʔ] "tree" |

[tʃeʔ] | /tʲeʔ/ | /teʔ/ | /teʔ/ | [teʔ] | [teʔ] | [tseːʔ] | [tseʔ] | [tʃeːʔ] | [tʃeʔ] |

| *[tʲaʔŋ] "ashes" |

[taʔn] | /taʔaŋ/ | [tan] | [taŋ] | [tsaːx] | [tsaʔ] | [tʃaːx] | [tʃax] |

The Proto-Mayan velar nasal *[ŋ] is reflected as [x] in the eastern branches (Quichean–Mamean), [n] in Qʼanjobalan, Chʼolan and Yucatecan, [h] in Huastecan, and only conserved as [ŋ] in Chuj and Jakaltek.[58][61][62]

| Proto-Mayan | Yucatec | Chʼortiʼ | Qʼanjobal | Chuj | Jakaltek (Poptiʼ) | Ixil | Kʼicheʼ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *[ŋeːh] "tail" |

[neːh] | /nex/ | [ne] | /ŋeh/ | [ŋe] | [xeh] | [xeːʔ] |

Diphthongs

Vowel quality is typically classified as having monophthongal vowels. In traditionally diphthongized contexts, Mayan languages will realize the V-V sequence by inserting a hiatus-breaking glottal stop or glide insertion between the vowels. Some Kʼichean-branch languages have exhibited developed diphthongs from historical long vowels, by breaking /e:/ and /o:/.[63]

Grammar

The morphology of Mayan languages is simpler than that of other Mesoamerican languages,[notes 14] yet its morphology is still considered agglutinating and polysynthetic.[64] Verbs are marked for aspect or tense, the person of the subject, the person of the object (in the case of transitive verbs), and for plurality of person. Possessed nouns are marked for person of possessor. In Mayan languages, nouns are not marked for case, and gender is not explicitly marked.

Word order

Proto-Mayan is thought to have had a basic verb–object–subject word order with possibilities of switching to VSO in certain circumstances, such as complex sentences, sentences where object and subject were of equal animacy and when the subject was definite.[notes 15] Today Yucatecan, Tzotzil and Tojolabʼal have a basic fixed VOS word order. Mamean, Qʼanjobʼal, Jakaltek and one dialect of Chuj have a fixed VSO one. Only Chʼortiʼ has a basic SVO word order. Other Mayan languages allow both VSO and VOS word orders.[65]

Numeral classifiers

In many Mayan languages, counting requires the use of numeral classifiers, which specify the class of items being counted; the numeral cannot appear without an accompanying classifier. Some Mayan languages, such as Kaqchikel, do not use numeral classifiers. Class is usually assigned according to whether the object is animate or inanimate or according to an object's general shape.[66] Thus when counting "flat" objects, a different form of numeral classifier is used than when counting round things, oblong items or people. In some Mayan languages such as Chontal, classifiers take the form of affixes attached to the numeral; in others such as Tzeltal, they are free forms. Jakaltek has both numeral classifiers and noun classifiers, and the noun classifiers can also be used as pronouns.[67]

The meaning denoted by a noun may be altered significantly by changing the accompanying classifier. In Chontal, for example, when the classifier -tek is used with names of plants it is understood that the objects being enumerated are whole trees. If in this expression a different classifier, -tsʼit (for counting long, slender objects) is substituted for -tek, this conveys the meaning that only sticks or branches of the tree are being counted:[68]

| untek wop (one-tree Jahuacte) | untsʼit wop (one-stick jahuacte) |

un- one- tek "plant" wop jahuacte tree "one jahuacte tree" |

un- one- tsʼit "long.slender.object" wop jahuacte tree "one stick from a jahuacte tree" |

Possession

The morphology of Mayan nouns is fairly simple: they inflect for number (plural or singular), and, when possessed, for person and number of their possessor. Pronominal possession is expressed by a set of possessive prefixes attached to the noun, as in Kaqchikel ru-kej "his/her horse". Nouns may furthermore adopt a special form marking them as possessed. For nominal possessors, the possessed noun is inflected as possessed by a third-person possessor, and followed by the possessor noun, e.g. Kaqchikel ru-kej ri achin "the man's horse" (literally "his horse the man").[69] This type of formation is a main diagnostic trait of the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area and recurs throughout Mesoamerica.[70]

Mayan languages often contrast alienable and inalienable possession by varying the way the noun is (or is not) marked as possessed. Jakaltek, for example, contrasts inalienably possessed wetʃel "my photo (in which I am depicted)" with alienably possessed wetʃele "my photo (taken by me)". The prefix we- marks the first person singular possessor in both, but the absence of the -e possessive suffix in the first form marks inalienable possession.[69]

Relational nouns

Mayan languages which have prepositions at all normally have only one. To express location and other relations between entities, use is made of a special class of "relational nouns". This pattern is also recurrent throughout Mesoamerica and is another diagnostic trait of the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area. In Mayan most relational nouns are metaphorically derived from body parts so that "on top of", for example, is expressed by the word for head.[71]

Subjects and objects

Mayan languages are ergative in their alignment. This means that the subject of an intransitive verb is treated similarly to the object of a transitive verb, but differently from the subject of a transitive verb.[72]

Mayan languages have two sets of affixes that are attached to a verb to indicate the person of its arguments. One set (often referred to in Mayan grammars as set B) indicates the person of subjects of intransitive verbs, and of objects of transitive verbs. They can also be used with adjective or noun predicates to indicate the subject.[73]

| Usage | Language of example | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject of an intransitive verb | Kaqchikel | x-ix-ok | "You [plural] entered" |

| Object of a transitive verb | Kaqchikel | x-ix-ru-chöp | "He/she took you [plural]" |

| Subject of an adjective predicate | Kaqchikel | ix-samajel | "You [plural] are hard-working." |

| Subject of a noun predicate | Tzotzil | ʼantz-ot | "You are a woman." |

Another set (set A) is used to indicate the person of subjects of transitive verbs (and in some languages, such as Yucatec, also the subjects of intransitive verbs, but only in the incompletive aspects), and also the possessors of nouns (including relational nouns).[notes 16]

| Usage | Language of example | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject of a transitive verb |

Kaqchikel | x-ix-ru-chöp | "He/she took you guys" |

| Possessive marker | Kaqchikel | ru-kej ri achin | "the man's horse" (literally: "his horse the man") |

| Relational marker | Classical Kʼicheʼ | u-wach ulew | "on the earth" (literally: "its face the earth", i.e. "face of the earth") |

Verbs

In addition to subject and object (agent and patient), the Mayan verb has affixes signalling aspect, tense, and mood as in the following example:

Aspect/mood/tense k- INCOMPL Class A prefix in- 1SG.P Class B prefix a- 2SG.A Root chʼay hit Aspect/mood/voice -o INCOMPL Plural

(Kʼicheʼ) kinachʼayo "You are hitting me" |

Tense systems in Mayan languages are generally simple. Jakaltek, for example, contrasts only past and non-past, while Mam has only future and non-future. Aspect systems are normally more prominent. Mood does not normally form a separate system in Mayan, but is instead intertwined with the tense/aspect system.[74] Kaufman has reconstructed a tense/aspect/mood system for proto-Mayan that includes seven aspects: incompletive, progressive, completive/punctual, imperative, potential/future, optative, and perfective.[75]

Mayan languages tend to have a rich set of grammatical voices. Proto-Mayan had at least one passive construction as well as an antipassive rule for downplaying the importance of the agent in relation to the patient. Modern Kʼicheʼ has two antipassives: one which ascribes focus to the object and another that emphasizes the verbal action.[76] Other voice-related constructions occurring in Mayan languages are the following: mediopassive, incorporational (incorporating a direct object into the verb), instrumental (promoting the instrument to object position) and referential (a kind of applicative promoting an indirect argument such as a benefactive or recipient to the object position).[77]

Statives and positionals

In Mayan languages, statives are a class of predicative words expressing a quality or state, whose syntactic properties fall in between those of verbs and adjectives in Indo-European languages. Like verbs, statives can sometimes be inflected for person but normally lack inflections for tense, aspect and other purely verbal categories. Statives can be adjectives, positionals or numerals.[78]

Positionals, a class of roots characteristic of, if not unique to, the Mayan languages, form stative adjectives and verbs (usually with the help of suffixes) with meanings related to the position or shape of an object or person. Mayan languages have between 250 and 500 distinct positional roots:[78]

Telan ay jun naq winaq yul bʼe.

- There is a man lying down fallen on the road.

Woqan hin kʼal ay max ekkʼu.

- I spent the entire day sitting down.

Yet ewi xoyan ay jun lobʼaj stina.

- Yesterday there was a snake lying curled up in the entrance of the house.

In these three Qʼanjobʼal sentences, the positionals are telan ("something large or cylindrical lying down as if having fallen"), woqan ("person sitting on a chairlike object"), and xoyan ("curled up like a rope or snake").[79]

Word formation

Compounding of noun roots to form new nouns is commonplace; there are also many morphological processes to derive nouns from verbs. Verbs also admit highly productive derivational affixes of several kinds, most of which specify transitivity or voice.[80]

As in other Mesoamerican languages, there is a widespread metaphorical use of roots denoting body parts, particularly to form locatives and relational nouns, such as Kaqchikel -pan ("inside" and "stomach") or -wi ("head-hair" and "on top of").[81]

Mayan loanwords

A number of loanwords of Mayan or potentially Mayan origins are found in many other languages, principally Spanish, English, and some neighboring Mesoamerican languages. In addition, Mayan languages borrowed words, especially from Spanish.[82]

A Mayan loanword is cigar. sic is Mayan for "tobacco" and sicar means "to smoke tobacco leaves". This is the most likely origin for cigar and thus cigarette.[83]

The English word "hurricane", which is a borrowing from the Spanish word huracán is considered to be related to the name of Maya storm deity Jun Raqan. However, it is probable that the word passed into European languages from a Cariban language or Taíno.[84]

Writing systems

The complex script used to write Mayan languages in pre-Columbian times and known today from engravings at several Maya archaeological sites has been deciphered almost completely. The script is a mix between a logographic and a syllabic system.[85]

In colonial times Mayan languages came to be written in a script derived from the Latin alphabet; orthographies were developed mostly by missionary grammarians.[86] Not all modern Mayan languages have standardized orthographies, but the Mayan languages of Guatemala use a standardized, Latin-based phonemic spelling system developed by the Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (ALMG).[16][17] Orthographies for the languages of Mexico are currently being developed by the Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI).[22][87]

Glyphic writing

The pre-Columbian Maya civilization developed and used an intricate and fully functional writing system, which is the only Mesoamerican script that can be said to be almost fully deciphered. Earlier-established civilizations to the west and north of the Maya homelands that also had scripts recorded in surviving inscriptions include the Zapotec, Olmec, and the Zoque-speaking peoples of the southern Veracruz and western Chiapas area—but their scripts are as yet largely undeciphered. It is generally agreed that the Maya writing system was adapted from one or more of these earlier systems. A number of references identify the undeciphered Olmec script as its most likely precursor.[88][89]

In the course of the deciphering of the Maya hieroglyphic script, scholars have come to understand that it was a fully functioning writing system in which it was possible to express unambiguously any sentence of the spoken language. The system is of a type best classified as logosyllabic, in which symbols (glyphs or graphemes) can be used as either logograms or syllables.[85] The script has a complete syllabary (although not all possible syllables have yet been identified), and a Maya scribe would have been able to write anything phonetically, syllable by syllable, using these symbols.[85]

At least two major Mayan languages have been confidently identified in hieroglyphic texts, with at least one other language probably identified. An archaic language variety known as Classic Maya predominates in these texts, particularly in the Classic-era inscriptions of the southern and central lowland areas. This language is most closely related to the Chʼolan branch of the language family, modern descendants of which include Chʼol, Chʼortiʼ and Chontal. Inscriptions in an early Yucatecan language (the ancestor of the main surviving Yucatec language) have also been recognised or proposed, mainly in the Yucatán Peninsula region and from a later period. Three of the four extant Maya codices are based on Yucatec. It has also been surmised that some inscriptions found in the Chiapas highlands region may be in a Tzeltalan language whose modern descendants are Tzeltal and Tzotzil.[29] Other regional varieties and dialects are also presumed to have been used, but have not yet been identified with certainty.[11]

Use and knowledge of the Maya script continued until the 16th century Spanish conquest at least. Bishop Diego de Landa Calderón of the Catholic Archdiocese of Yucatán prohibited the use of the written language, effectively ending the Mesoamerican tradition of literacy in the native script. He worked with the Spanish colonizers to destroy the bulk of Mayan texts as part of his efforts to convert the locals to Christianity and away from what he perceived as pagan idolatry. Later he described the use of hieroglyphic writing in the religious practices of Yucatecan Maya in his Relación de las cosas de Yucatán.[90]

Colonial orthography

Colonial orthography is marked by the use of c for /k/ (always hard, as in cic /kiik/), k for /q/ in Guatemala or for /kʼ/ in the Yucatán, h for /x/, and tz for /ts/; the absence of glottal stop or vowel length (apart sometimes for a double vowel letter for a long glottalized vowel, as in uuc /uʼuk/), the use of u for /w/, as in uac /wak/, and the variable use of z, ç, s for /s/. The greatest difference from modern orthography, however, is in the various attempts to transcribe the ejective consonants.[91]

About 1550, Francisco de la Parra invented distinctive letters for ejectives in the Mayan languages of Guatemala, the tresillo and cuatrillo (and derivatives). These were used in all subsequent Franciscan writing, and are occasionally seen even today [2005]. In 1605, Alonso Urbano doubled consonants for ejectives in Otomi (pp, tt, ttz, cc / cqu), and similar systems were adapted to Mayan. Another approach, in Yucatec, was to add a bar to the letter, or to double the stem.[91]

| Phoneme | Yucatec | Parra |

|---|---|---|

| pʼ | pp, ꝑ, ꝑꝑ, 𝕡* | |

| tʼ | th, tħ, ŧ | tt, th |

| tsʼ | ɔ, dz | ꜯ |

| tʃʼ | cħ | ꜯh |

| kʼ | k | ꜭ |

| qʼ | ꜫ |

*Only the stem of 𝕡 is doubled, but that is not supported by Unicode.

A ligature ꜩ for tz is used alongside ꜭ and ꜫ. The Yucatec convention of dz for /tsʼ/ is retained in Maya family names such as Dzib.

Modern orthography

Since the colonial period, practically all Maya writing has used a Latin alphabet. Formerly these were based largely on the Spanish alphabet and varied between authors, and it is only recently that standardized alphabets have been established. The first widely accepted alphabet was created for Yucatec Maya by the authors and contributors of the Diccionario Maya Cordemex, a project directed by Alfredo Barrera Vásquez and first published in 1980.[notes 17] Subsequently, the Guatemalan Academy of Mayan Languages (known by its Spanish acronym ALMG), founded in 1986, adapted these standards to 22 Mayan languages (primarily in Guatemala). The script is largely phonemic, but abandoned the distinction between the apostrophe for ejective consonants and the glottal stop, so that ejective /tʼ/ and the non-ejective sequence /tʔ/ (previously tʼ and t7) are both written tʼ.[92] Other major Maya languages, primarily in the Mexican state of Chiapas, such as Tzotzil, Tzeltal, Chʼol, and Tojolabʼal, are not generally included in this reformation, and are sometimes written with the conventions standardized by the Chiapan "State Center for Indigenous Language, Art, and Literature" (CELALI), which for instance writes "ts" rather than "tz" (thus Tseltal and Tsotsil).

| Vowels | Consonants | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA |

| a | [a] | aa | [aː] | ä | [ɐ] | bʼ | [ɓ] | b | [b] | ch | [t͡ʃ] | chʼ | [t͡ʃʼ] | h | [h] |

| e | [e] | ee | [eː] | ë | [ɛ] | j | [χ] | l | [l] | k | [k] | kʼ | [kʼ] | m | [m] |

| i | [i] | ii | [iː] | ï | [ɪ] | y | [j] | p | [p] | q | [q] | qʼ | [qʼ] | n | [n] |

| o | [o] | oo | [oː] | ö | [ɤ̞] | s | [s] | x | [ʃ] | t | [t] | tʼ | [tʼ] | nh | [ŋ] |

| u | [u] | uu | [uː] | ü | [ʊ] | w | [w] | r | [r] | tz | [t͡s] | tzʼ | [t͡sʼ] | ʼ | [ʔ] |

|

In tonal languages (primarily Yucatec), a high tone is indicated with an accent, as with "á" or "ée". | |||||||||||||||

For the languages that make a distinction between palato-alveolar and retroflex affricates and fricatives (Mam, Ixil, Tektitek, Awakatek, Qʼanjobʼal, Poptiʼ, and Akatek in Guatemala, and Yucatec in Mexico) the ALMG suggests the following set of conventions.

| ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ch | [tʃ] | chʼ | [tʃʼ] | x | [ʃ] |

| tx | [tʂ] | txʼ | [tʂʼ] | xh | [ʂ] |

Literature

From the classic language to the present day, a body of literature has been written in Mayan languages. The earliest texts to have been preserved are largely monumental inscriptions documenting rulership, succession, and ascension, conquest and calendrical and astronomical events. It is likely that other kinds of literature were written in perishable media such as codices made of bark, only four of which have survived the ravages of time and the campaign of destruction by Spanish missionaries.[93]

Shortly after the Spanish conquest, the Mayan languages began to be written with Latin letters. Colonial-era literature in Mayan languages include the famous Popol Vuh, a mythico-historical narrative written in 17th century Classical Quiché but believed to be based on an earlier work written in the 1550s, now lost. The Título de Totonicapán and the 17th century theatrical work the Rabinal Achí are other notable early works in Kʼicheʼ, the latter in the Achí dialect.[notes 18] The Annals of the Cakchiquels from the late 16th century, which provides a historical narrative of the Kaqchikel, contains elements paralleling some of the accounts appearing in the Popol Vuh. The historical and prophetical accounts in the several variations known collectively as the books of Chilam Balam are primary sources of early Yucatec Maya traditions.[notes 19] The only surviving book of early lyric poetry, the Songs of Dzitbalche by Ah Bam, comes from this same period.[94]

In addition to these singular works, many early grammars of indigenous languages, called "artes", were written by priests and friars. Languages covered by these early grammars include Kaqchikel, Classical Quiché, Tzeltal, Tzotzil and Yucatec. Some of these came with indigenous-language translations of the Catholic catechism.[86]

While Mayan peoples continued to produce a rich oral literature in the postcolonial period (after 1821), very little written literature was produced in this period.[95][notes 20]

Because indigenous languages were excluded from the education systems of Mexico and Guatemala after independence, Mayan peoples remained largely illiterate in their native languages, learning to read and write in Spanish, if at all.[96] However, since the establishment of the Cordemex [97] and the Guatemalan Academy of Mayan Languages (1986), native language literacy has begun to spread and a number of indigenous writers have started a new tradition of writing in Mayan languages.[87][96] Notable among this new generation is the Kʼicheʼ poet Humberto Ak'abal, whose works are often published in dual-language Spanish/Kʼicheʼ editions,[98] as well as Kʼicheʼ scholar Luis Enrique Sam Colop (1955–2011) whose translations of the Popol Vuh into both Spanish and modern Kʼicheʼ achieved high acclaim.[99]

See also

- Mayan Sign Language

- Cauque Mayan (mixed language)

Notes

- In linguistics, it is conventional to use Mayan when referring to the languages, or an aspect of a language. In other academic fields, Maya is the preferred usage, serving as both a singular and plural noun, and as the adjectival form.

- Achiʼ is counted as a variant of Kʼicheʼ by the Guatemalan government.

- Based on Kaufman (1976).

- see attribution in Fernández de Miranda (1968, p. 75)

- This theory was first proposed by Campbell & Kaufman (1976)

- The last independent Maya kingdom (Tayasal) was not conquered until 1697, some 170 years after the first conquistadores arrived. During the Colonial and Postcolonial periods, Maya peoples periodically rebelled against the colonizers, such as the Caste War of Yucatán, which extended into the 20th century.

- Grenoble & Whaley (1998) characterized the situation this way: "Mayan languages typically have several hundreds of thousands of speakers, and a majority of Mayas speak a Mayan language as a first language. The driving concern of Maya communities is not to revitalize their language but to buttress it against the increasingly rapid spread of Spanish ... [rather than being] at the end of a process of language shift, [Mayan languages are] ... at the beginning."Grenoble & Whaley (1998, pp. xi–xii)

- Choi (2002) writes: "In the recent Maya cultural activism, maintenance of Mayan languages has been promoted in an attempt to support 'unified Maya identity'. However, there is a complex array of perceptions about Mayan language and identity among Maya who I researched in Momostenango, a highland Maya community in Guatemala. On the one hand, Maya denigrate Kʼicheʼ and have doubts about its potential to continue as a viable language because the command of Spanish is an economic and political necessity. On the other hand, they do recognize the value of Mayan language when they wish to claim the 'authentic Maya identity'. It is this conflation of conflicting and ambivalent ideologies that inform language choice..."

- See Suárez (1983) chapter 2 for a thorough discussion of the usage and meanings of the words "dialect" and "language" in Mesoamerica.

- Chontal Maya is not to be confused with the Tequistlatecan languages that are referred to as "Chontal of Oaxaca".

- The Ethnologue considers the dialects spoken in Cubulco and Rabinal to be distinct languages, two of the eight languages of a Quiché-Achi family. Raymond G., Gordon Jr. (ed.). Ethnologue, (2005). Language Family Tree for Mayan, accessed March 26, 2007.

- Proto-Mayan allowed roots of the shape CVC, CVVC, CVhC, CVʔC, and CVSC (where S is /s/, /ʃ/, or /x/)); see England (1994, pp. 77)

- Campbell (2015) mistakenly writes Tzeltal for Tzotzil, Avelino & Shin (2011) states that the reports of a fully developed tone contrast in San Bartolome Tzotzil are inaccurate

- Suárez (1983, p. 65) writes: "Neither Tarascan nor Mayan have words as complex as those found in Nahuatl, Totonac or Mixe–Zoque, but, in different ways both have a rich morphology."

- Lyle Campbell (1997) refers to studies by Norman and Campbell ((1978) "Toward a proto-Mayan syntax: a comparative perspective on grammar", in Papers in Mayan Linguistics, ed. Nora C. England, pp. 136–56. Columbia: Museum of Anthropology, University of Missouri) and by England (1991).

- Another view has been suggested by Carlos Lenkersdorf, an anthropologist who studied the Tojolabʼal language. He argued that a native Tojolabʼal speaker makes no cognitive distinctions between subject and object, or even between active and passive, animate and inanimate, seeing both subject and object as active participants in an action. For instance, in Tojolabʼal rather than saying "I teach you", one says the equivalent of "I-teach you-learn". See Lenkersdorf (1996, pp. 60–62)

- The Cordemex contains a lengthy introduction on the history, importance, and key resources of written Yucatec Maya, including a summary of the orthography used by the project (pp. 39a-42a).

- See Edmonson (1985) for a thorough treatment of colonial Quiché literature.

- Read Edmonson & Bricker (1985) for a thorough treatment of colonial Yucatec literature.

- See Gossen (1985) for examples of the Tzotzil tradition of oral literature.

Citations

- Spence et al. 1998.

- Campbell (1997, p. 165)

- Kettunen & Helmke 2020, p. 6.

- England 1994.

- Campbell 1997, p. 165.

- Kaufman & with Justeson 2003.

- Campbell & Kaufman 1985.

- Kaufman 1976.

- Robertson & Houston 2002.

- Hruby & Child 2004.

- Kettunen & Helmke (2020, p. 13)

- Houston, Robertson & Stuart 2000.

- Mora-Marín 2009.

- Choi 2002.

- Fabri 2003, p. 61. n1.

- French (2003)

- England (2007, pp. 14, 93)

- Campbell, Kaufman & Smith-Stark 1986.

- Campbell 1997, pp. passim.

- Mora-Marín 2016.

- Campbell 2015, p. 54.

- Campbell 2015.

- Bennett, Coon & Henderson 2015.

- Law 2013.

- Robertson 1977.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005). Ethnologue report on Chʼol de Tila, Ethnologue report on Chʼol de Tumbalá, both accessed March 07, 2007.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005). Ethnologue report on Chontal de Tabasco, accessed March 07, 2007.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005). Chʼortiʼ: A language of Guatemala. Ethnologue.com, accessed March 07, 2007.

- Kettunen & Helmke 2020, p. 13.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005) Family Tree for Tzeltalan accessed March 26, 2007.

- Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charl47547es D. Fennig (eds.). "Tzeltal" Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Eighteenth edition, (2015). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.). Ethnologue, (2005).

- Solá 2011.

- Popkin 2005.

- Rao 2015.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005). Gordon (2005) recognizes Eastern and Western dialects of Jakaltek, as well as Mochoʼ (also called Mototzintlec), a language with less than 200 speakers in the Chiapan villages of Tuzantán and Mototzintla.

- Jakaltek is spoken in the municipios of Jacaltenango, La Democracia, Concepción, San Antonio Huista and Santa Ana Huista, and in parts of the Nentón municipio.

- Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). "Akateko" Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Eighteenth edition, (2015). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005) Tojolabal: A language of Mexico. and Chuj: A language of Guatemala. Archived 2007-10-01 at the Wayback Machine both accessed March 19, 2007.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005). Ethnologue report on Qʼeqchi, accessed March 07, 2007.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005) Ethnologue report for Uspantec, accessed March 26, 2007.

- Edmonson 1968, pp. 250–251.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005). Family Tree for Kaqchikel, accessed March 26, 2007.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005). Ethnologue report on Eastern Tzʼutujil, Ethnologue report on Western Tzʼutujil Archived 2007-04-10 at the Wayback Machine, both accessed March 26, 2007.

- Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). "Sakapulteko" Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Eighteenth edition, (2015). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). "Sipakapense" Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Eighteenth edition, (2015). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005) Ethnologue report on Nebaj Ixil Archived 2008-05-04 at the Wayback Machine, Chajul Ixil Archived 2006-12-08 at the Wayback Machine & San Juan Cotzal Ixil, accessed March 07, 2008.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005) Ethnologue report for Tektitek, accessed March 07, 2007.

- Campbell 1997, p. 163.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005). Ethnologue report on Eastern Poqomam, Ethnologue report on Western Poqomchiʼ, both accessed March 07, 2007.

- Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). "Poqomam" Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Eighteenth edition, (2015). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- Población hablante de lengua indígena de 5 y más años por principales lenguas, 1970 a 2005 Archived 2007-08-25 at the Wayback Machine INEGI

- Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). "Maya, Yucatec" Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Eighteenth edition, (2015). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- There were only 12 remaining native speakers in 1986 according to Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.). Ethnologue, (2005).

- Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). "Lacandon" Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Eighteenth edition, (2015). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.). Ethnologue (2005).

- Campbell & Canger 1978.

- England (1994, pp. 30–31)

- England 1994, p. 35.

- Adapted from cognate list in England (1994).

- Kerry Hull ''An Abbreviated Dictionary of Ch’orti’ Maya''. 2005

- Nicholas A. Hopkins. ''A DICTIONARY OF THE CHUJ (MAYAN) LANGUAGE''. 2012

- England 2001.

- Suárez 1983, p. 65.

- England 1991.

- See, e.g., Tozzer (1977 [1921]), pp. 103, 290–292.

- Craig 1977, p. 141.

- Example follows Suárez (1983, p. 88)

- Suárez (1983, p. 85)

- Campbell, Kaufman & Smith-Stark 1986, pp. 544–545.

- Campbell, Kaufman & Smith-Stark 1986, pp. 545–546.

- Coon 2010, pp. 47–52.

- Suárez 1983, p. 77.

- Suaréz (1983), p. 71.

- England 1994, p. 126.

- Campbell (1997, p. 164)

- England 1994, p. 97–103.

- Coon & Preminger 2009.

- England 1994, p. 87.

- Suárez 1983, p. 65–67.

- Campbell, Kaufman & Smith-Stark 1986, p. 549.

- Hofling, Charles Andrew (2011). Mopan Maya-Spanish-English Dictionary. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-1607810292.

- Cigar, Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Read & González (2000), p.200

- Kettunen & Helmke (2020, p. 8)

- Suárez 1983, p. 5.

- Maxwell 2011.

- Schele & Freidel 1990.

- Soustelle 1984.

- Kettunen & Helmke 2020, pp. 9–11.

- Arzápalo Marín (2005)

- Josephe DeChicchis, "Revisiting an imperfection in Mayan orthography" Archived 2014-11-03 at the Wayback Machine , Journal of Policy Studies 37 (March 2011)

- Coe 1987, p. 161.

- Curl 2005.

- Suárez 1983, pp. 163–168.

- Maxwell 2015.

- Barrera Vásquez, Bastarrachea Manzano & Brito Sansores 1980.

- "Humberto Ak´abal" (in Spanish). Guatemala Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes. March 26, 2007. Archived from the original on February 14, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- "Luis Enrique Sam Colop, 1955–2011 | American Indian Studies". Ais.arizona.edu. Retrieved 2011-12-19.

References

- Arzápalo Marín, R. (2005). "La representación escritural del maya de Yucatán desde la época prehispánica hasta la colonia: Proyecciones hacia el siglo XXI". In Zwartjes; Altman (eds.). Missionary Linguistics II: Orthography and Phonology. Walter Benjamins.

- Avelino, H.; Shin, E. (2011). "Chapter I The Phonetics of Laryngalization in Yucatec Maya". In Avelino, Heriberto; Coon, Jessica; Norcliffe, Elisabeth (eds.). New perspectives in Mayan linguistics. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Barrera Vásquez, Alfredo; Bastarrachea Manzano, Juan Ramón; Brito Sansores, William (1980). Diccionario maya Cordemex : maya-español, español-maya. Mérida, Yucatán, México: Ediciones Cordemex. OCLC 7550928. (in Spanish and Yucatec Maya)

- Bennett, Ryan; Coon, Jessica; Henderson, Robert (2015). "Introduction to Mayan Linguistics" (PDF). Language and Linguistics Compass.

- Bolles, David (2003) [1997]. "Combined Dictionary–Concordance of the Yucatecan Mayan Language" (Revized ed.). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI). Retrieved 2006-12-12. (in Yucatec Maya and English)

- Bolles, David; Bolles, Alejandra (2004). "A Grammar of the Yucatecan Mayan Language" (revised online edition, 1996 Lee, New Hampshire). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI). The Foundation Research Department. Retrieved 2006-12-12. (in Yucatec Maya and English)

- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics, no. 4. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Campbell, Lyle; Canger, Una (1978). "Chicomuceltec's last throes". International Journal of American Linguistics. 44 (3): 228–230. doi:10.1086/465548. ISSN 0020-7071. S2CID 144743316.

- Campbell, Lyle; Kaufman, Terrence (1976). "A Linguistic Look at the Olmec". American Antiquity. 41 (1): 80–89. doi:10.2307/279044. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 279044. S2CID 162230234.

- Campbell, Lyle; Kaufman, Terrence (October 1985). "Mayan Linguistics: Where are We Now?". Annual Review of Anthropology. 14 (1): 187–198. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.14.100185.001155.

- Campbell, Lyle; Kaufman, Terrence; Smith-Stark, Thomas C. (1986). "Meso-America as a linguistic area". Language. 62 (3): 530–570. doi:10.1353/lan.1986.0105. S2CID 144784988.

- Campbell, Lyle (2015). "History and reconstruction of the Mayan languages". In Aissen, Judith; England, Nora C.; Maldonado, Roberto Zavala (eds.). The Mayan Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 43–61.

- Choi, Jinsook (2002). The Role of Language in Ideological Construction of Mayan Identities in Guatemala (PDF). Texas Linguistic Forum 45: Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Symposium about Language and Society—Austin, April 12–14. pp. 22–31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-19.

- Coe, Michael D. (1987). The Maya (4th revised ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27455-X.

- Coe, Michael D. (1992). Breaking the Maya Code. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05061-9. OCLC 26605966.

- Coon, Jessica (2010). Complementation in Chol (Mayan): A Theory of Split Ergativity (electronic version) (PhD). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- Coon, J.; Preminger, O. (2009). "Positional roots and case absorption". In Heriberto Avelino (ed.). New Perspectives in Mayan Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 35–58.

- Craig, Colette Grinevald (1977). The Structure of Jacaltec. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292740051.

- Curl, John (2005). Ancient American Poets. Tempe, AZ: Bilingual Press. ISBN 1-931010-21-8.

- Dienhart, John M. (1997). "The Mayan Languages- A Comparative Vocabulary". Odense University. Archived from the original (electronic version) on 2006-12-08. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- Edmonson, Munro S. (1968). "Classical Quiché". In Norman A. McQuown (Volume ed.) (ed.). Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 5: Linguistics. R. Wauchope (General Editor). Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 249–268. ISBN 0-292-73665-7.

- Edmonson, Munro S. (1985). "Quiche Literature". In Victoria Reifler Bricker (volume ed.) (ed.). Supplement to the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Volume 3. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-77593-8.

- Edmonson, Munro S.; Bricker, Victoria R. (1985). "Yucatecan Mayan Literature". In Victoria Reifler Bricker (volume ed.) (ed.). Supplement to the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Volume 3. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-77593-8.

- England, Nora C. (1994). Autonomia de los Idiomas Mayas: Historia e identidad. (Ukutaʼmiil Ramaqʼiil Utzijobʼaal ri Mayaʼ Amaaqʼ.) (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Guatemala City: Cholsamaj. ISBN 84-89451-05-2.

- England, Nora C. (2007). "The influence of Mayan-speaking linguists on the state of Mayan linguistics". Linguistische Berichte, Sonderheft. 14: 93–112.

- England, Nora C. (2001). Introducción a la gramática de los idiomas mayas (in Spanish). Cholsamaj Fundacion.

- England, N. C. (1991). "Changes in basic word order in Mayan languages". International Journal of American Linguistics. 57 (4): 446–486. doi:10.1086/ijal.57.4.3519735. S2CID 146516836.

- Fabri, Antonella (2003). "Genocide or Assimilation: Discourses of Women's Bodies, Health, and Nation in Guatemala". In Richard Harvey Brown (ed.). The Politics of Selfhood: Bodies and Identities in Global Capitalism. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3754-7.

- Fernández de Miranda, María Teresa (1968). "Inventory of Classificatory Materials". In Norman A. McQuown (Volume ed.) (ed.). Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 5: Linguistics. R. Wauchope (General Editor). Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 63–78. ISBN 0-292-73665-7.

- French, Brigittine M. (2003). "The politics of Mayan linguistics in Guatemala: native speakers, expert analysts, and the nation". Pragmatics. 13 (4): 483–498. doi:10.1075/prag.13.4.02fre. S2CID 145598734.

- Gossen, Gary (1985). "Tzotzil Literature". In Victoria Reifler Bricker (ed.). Supplement to the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Volume 3. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-77593-8.

- Grenoble, Lenore A.; Whaley, Lindsay J. (1998). "Preface" (PDF). In Lenore A. Grenoble; Lindsay J. Whaley (eds.). Endangered languages: Current issues and future prospects. Cambridge University Press. pp. xi–xii. ISBN 0-521-59102-3.

- Houston, Stephen D.; Robertson, John; Stuart, David (2000). "The Language of Classic Maya Inscriptions". Current Anthropology. 41 (3): 321–356. doi:10.1086/300142. ISSN 0011-3204. PMID 10768879. S2CID 741601.

- Hruby, Z. X.; Child, M. B. (2004). "Chontal linguistic influence in Ancient Maya writing". In S. Wichmann (ed.). The linguistics of Maya writin. pp. 13–26.

- Kaufman, Terrence (1976). "Archaeological and Linguistic Correlations in Mayaland and Associated Areas of Meso-America". World Archaeology. 8 (1): 101–118. doi:10.1080/00438243.1976.9979655. ISSN 0043-8243.

- Kaufman, Terrence; with Justeson, John (2003). "A Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary" (PDF). FAMSI.

- Kettunen, Harri; Helmke, Christophe (2020). Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs (PDF). Wayeb. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- Law, D. (2013). "Mayan historical linguistics in a new age". Language and Linguistics Compass. 7 (3): 141–156. doi:10.1111/lnc3.12012.

- Lenkersdorf, Carlos (1996). Los hombres verdaderos. Voces y testimonios tojolabales. Lengua y sociedad, naturaleza y cultura, artes y comunidad cósmica (in Spanish). Mexico City: Siglo XXI. ISBN 968-23-1998-6.

- Longacre, Robert (1968). "Systemic Comparison and Reconstruction". In Norman A. McQuown (Volume ed.) (ed.). Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 5: Linguistics. R. Wauchope (General Editor). Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 117–159. ISBN 0-292-73665-7.

- Maxwell, Judith M. (2015). "Change in Literacy and Literature in Highland Guatemala, Precontact to Present". Ethnohistory. 62 (3): 553–572. doi:10.1215/00141801-2890234.

- Maxwell, Judith M. (2011). "The path back to literacy". In Smith, T. J.; Adams, A. E. (eds.). After the Coup: An Ethnographic Reframing of Guatemala 1954. University of Illinois Press.

- Mora-Marín, David (2009). "A Test and Falsification of the 'Classic Chʼoltiʼan' Hypothesis: A Study of Three Proto Chʼolan Markers". International Journal of American Linguistics. 75 (2): 115–157. doi:10.1086/596592. S2CID 145216002.

- Mora-Marín, David (2016). "Testing the Proto-Mayan-Mije-Sokean Hypothesis". International Journal of American Linguistics. 82 (2): 125–180. doi:10.1086/685900. S2CID 147269181.

- McQuown, Norman A. (1968). "Classical Yucatec (Maya)". In Norman A. McQuown (Volume ed.) (ed.). Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 5: Linguistics. R. Wauchope (General Editor). Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 201–248. ISBN 0-292-73665-7.

- Oxlajuuj Keej Mayaʼ Ajtzʼiibʼ (OKMA) (1993). Mayaʼ chiiʼ. Los idiomas Mayas de Guatemala. Guatemala City: Cholsamaj. ISBN 84-89451-52-4.

- Popkin, E (2005). "The emergence of pan-Mayan ethnicity in the Guatemalan transnational community linking Santa Eulalia and Los Angeles". Current Sociology. 53 (4): 675–706. doi:10.1177/0011392105052721. S2CID 143851930.

- Rao, S. (2015). Language Futures from Uprooted Pasts: Emergent Language Activism in the Mayan Diaspora of the United States (Thesis). UCLA, MA thesis.

- Read, Kay Almere; González, Jason (2000). Handbook of Mesoamerican Mythology. Oxford: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-340-0. OCLC 43879188.

- Robertson, John (1977). "Proposed revision in Mayan subgrouping". International Journal of American Linguistics. 43 (2): 105–120. doi:10.1086/465466. S2CID 143665564.

- Robertson, John (1992). The History of Tense/Aspect/Mood/Voice in the Mayan Verbal Complex. University of Texas Press.

- Robertson, John; Houston, Stephen (2002). "El problema del Wasteko: Una perspectiva lingüística y arqueológica". In J.P. Laporte; B. Arroyo; H. Escobedo; H. Mejía (eds.). XVI Simposio de InvestigacionesArqueológicas en Guatemala. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala. pp. 714–724.

- Sapper, Karl (1912). Über einige Sprachen von Südchiapas. Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Congress of Americanists (1910) (in German). pp. 295–320.

- Schele, Linda; Freidel, David (1990). A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-07456-1.

- Solá, J. O. (2011). "The origins and formation of the Latino community in Northeast Ohio, 1900 to 2009". Ohio History. 118 (1): 112–129. doi:10.1353/ohh.2011.0014. S2CID 145103773.

- Soustelle, Jacques (1984). The Olmecs: The Oldest Civilization in Mexico. New York: Doubleday and Co. ISBN 0-385-17249-4.

- Spence, Jack; Dye, David R.; Worby, Paula; de Leon-Escribano, Carmen Rosa; Vickers, George; Lanchin, Mike (August 1998). "Promise and Reality: Implementation of the Guatemalan Peace Accords". Hemispheres Initiatives. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- Suárez, Jorge A. (1983). The Mesoamerican Indian Languages. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22834-4.

- Tozzer, Alfred M. (1977) [1921]. A Maya Grammar (unabridged republication ed.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23465-7.

- Wichmann, S. (2006). "Mayan historical linguistics and epigraphy: a new synthesis". Annual Review of Anthropology. 35: 279–294. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123257. S2CID 18014314.

- Wichmann, Søren; Brown, Cecil H. (2003). "Contact among some Mayan languages: Inferences from loanwords". Anthropological Linguistics: 57–93.

- Wichmann, Søren, ed. (2004). The linguistics of Maya writing. Utah University Press.

External links

- The Guatemalan Academy of Mayan Languages – Spanish/Mayan site, the primary authority on Mayan Languages (in Spanish)

- Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Program at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University

- Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Volumes 1–9. Published by the Peabody Museum Press and distributed by Harvard University Press

- Swadesh lists for Mayan languages (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Mayan languages and linguistics books from Cholsamaj

- Online bibliography of Mayan languages at the University of Texas

- Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan Mayan-Spanish dictionary (Spanish)