Sumerian language

Sumerian (Cuneiform: 𒅴𒂠 Emegir "native tongue") is the language of ancient Sumer. It is one of the oldest attested languages, dating back to at least 3000 BC.[1] It is accepted to be a local language isolate and to have been spoken in ancient Mesopotamia, in the area that is modern-day Iraq.

| Sumerian | |

|---|---|

| 𒅴𒂠 Emegir | |

| Native to | Sumer and Akkad |

| Region | Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) |

| Era | Attested from c. 3000 BC. Effectively extinct from about 2000–1800 BC; used as classical language until about 100 AD. |

| Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | sux |

| ISO 639-3 | sux |

| Glottolog | sume1241 |

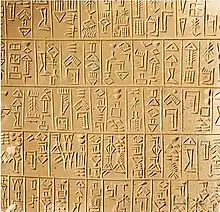

A list of gifts, Adab, 26th century BC | |

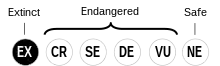

Sumerian is an extinct language according to the classification system of the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Akkadian, a Semitic language, gradually replaced Sumerian as a spoken language in the area around 2000 BC (the exact date is debated),[2] but Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary and scientific language in Akkadian-speaking Mesopotamian states such as Assyria and Babylonia until the 1st century AD.[3][4] Thereafter it seems to have fallen into obscurity until the 19th century, when Assyriologists began deciphering the cuneiform inscriptions and excavated tablets that had been left by its speakers.

Stages

The history of written Sumerian can be divided into several periods:

- Archaic Sumerian – 31st–26th century BC

- Old or Classical Sumerian – 26th–23rd century BC

- Neo-Sumerian – 23rd–21st century BC

- Late Sumerian – 20th–18th century BC

- Post-Sumerian – after 1700 BC.

Archaic Sumerian is the earliest stage of inscriptions with linguistic content, beginning with the Jemdet Nasr (Uruk III) period from about the 31st to 30th centuries BC. It succeeds the proto-literate period, which spans roughly the 35th to 30th centuries.

Some versions of the chronology may omit the Late Sumerian phase and regard all texts written after 2000 BC as Post-Sumerian.[7] The term "Post-Sumerian" is meant to refer to the time when the language was already extinct and preserved by Babylonians and Assyrians only as a liturgical and classical language for religious, artistic and scholarly purposes. The extinction has traditionally been dated approximately to the end of the Third Dynasty of Ur, the last predominantly Sumerian state in Mesopotamia, about 2000 BC. However, that date is very approximate, as many scholars have contended that Sumerian was already dead or dying as early as around 2100 BC, by the beginning of the Ur III period,[2][8] and others believe that Sumerian persisted, as a spoken language, in a small part of Southern Mesopotamia (Nippur and its surroundings) until as late as 1700 BC.[2] Whatever the status of spoken Sumerian between 2000 and 1700 BC, it is from then that a particularly large quantity of literary texts and bilingual Sumerian-Akkadian lexical lists survive, especially from the scribal school of Nippur. They and the particularly intensive official and literary use of the language in Akkadian-speaking states during the same time call for a distinction between the Late Sumerian and the Post-Sumerian periods. Sumerian school documents from the Sealand Dynasty were found at Tell Khaiber, some of which contain year names from the reign of a king with the Sumerian throne name Aya-dara-galama.[9]

Dialects

The standard variety of Sumerian was Emegir (𒅴𒂠 eme-gir₁₅). A notable variety or sociolect was Emesal (𒅴𒊩 eme-sal), possibly to be interpreted as "fine tongue" or "high-pitched voice" (Rubio 2007, p. 1369). Other terms for dialects or registers were eme-galam "high tongue", eme-si-sa "straight tongue", eme-te-na "oblique[?] tongue", etc.[10]

Emesal is used exclusively by female characters in some literary texts (that may be compared to the female languages or language varieties that exist or have existed in some cultures, such as among the Chukchis and the Garifuna). In addition, it is dominant in certain genres of cult songs such as the hymns sung by Gala priests.[11] The special features of Emesal are mostly phonological (for example, m is often used instead of g̃ [i.e. [ŋ]], as in me instead of standard g̃e26 for "I"), but words different from the standard language are also used (ga-ša-an rather than standard nin, "lady").[12]

Classification

Sumerian is a language isolate.[13][14][15][16] Ever since decipherment, it has been the subject of much effort to relate it to a wide variety of languages. Because it has a peculiar prestige as one of the most ancient written languages, proposals for linguistic affinity sometimes have a nationalistic background. Such proposals enjoy virtually no support among linguists because of their unverifiability.[17] Sumerian was at one time widely held to be an Indo-European language, but that view later came to be almost universally rejected.[18]

Among its proposed linguistic affiliates are:

- Kartvelian languages[19][20] (Nicholas Marr)

- Austroasiatic languages, specifically Munda languages (Igor M. Diakonoff[21])

- Dravidian languages (A. Sathasivam) [22]

- Uralic languages (Simo Parpola[23]) or, more generally, Ural–Altaic languages (Simo Parpola,[23] C. G. Gostony,[24] András Zakar,[25] Ida Bobula[26][27])

- Basque language[26]

- Nostratic languages (Allan Bomhard[26][28])

- Sino-Tibetan languages, specifically Tibeto-Burman languages (Jan Braun,[29] following C. J. Ball, V. Christian, K. Bouda,[30] and V. Emeliyanov)

- Dené–Caucasian languages (John Bengtson[31])

It has also been suggested that the Sumerian language descended from a late prehistoric creole language (Høyrup 1992).[26][32] However, no conclusive evidence, only some typological features, can be found to support Høyrup's view.

A more widespread hypothesis posits a Proto-Euphratean language that preceded Sumerian in Southern Mesopotamia and exerted an areal influence on it, especially in the form of polysyllabic words that appear "un-Sumerian"—making them suspect of being loanwords—and are not traceable to any other known language. There is little speculation as to the affinities of this substratum language, or these languages, and it is thus best treated as unclassified. Researchers such as Gonzalo Rubio[33] disagree with the assumption of a single substratum language and argue that several languages are involved. A related proposal by Gordon Whittaker[34] is that the language of the proto-literary texts from the Late Uruk period (c. 3350–3100 BC) is really an early Indo-European language which he terms "Euphratic".

Writing system

Development

_circa_2400_BCE.jpg.webp)

The Sumerian language is one of the earliest known written languages. The "proto-literate" period of Sumerian writing spans c. 3300 to 3000 BC. In this period, records are purely logographic, with no phonological content. The oldest document of the proto-literate period is the Kish tablet. Falkenstein (1936) lists 939 signs used in the proto-literate period (late Uruk, 34th to 31st centuries).

Records with unambiguously linguistic content, identifiably Sumerian, are those found at Jemdet Nasr, dating to the 31st or 30th century BC. From about 2600 BC, the logographic symbols were generalized using a wedge-shaped stylus to impress the shapes into wet clay. This cuneiform ("wedge-shaped") mode of writing co-existed with the pre-cuneiform archaic mode. Deimel (1922) lists 870 signs used in the Early Dynastic IIIa period (26th century). In the same period the large set of logographic signs had been simplified into a logosyllabic script comprising several hundred signs. Rosengarten (1967) lists 468 signs used in Sumerian (pre-Sargonian) Lagash. The pre-Sargonian period of the 26th to 24th centuries BC is the "Classical Sumerian" stage of the language.

The cuneiform script was adapted to Akkadian writing beginning in the mid-third millennium. Over the long period of bi-lingual overlap of active Sumerian and Akkadian usage the two languages influenced each other, as reflected in numerous loanwords and even word order changes.[35]

Transcription

Depending on the context, a cuneiform sign can be read either as one of several possible logograms, each of which corresponds to a word in the Sumerian spoken language, as a phonetic syllable (V, VC, CV, or CVC), or as a determinative (a marker of semantic category, such as occupation or place). (See the article Transliterating cuneiform languages.) Some Sumerian logograms were written with multiple cuneiform signs. These logograms are called diri-spellings, after the logogram 'diri' which is written with the signs SI and A. The text transliteration of a tablet will show just the logogram, such as the word 'diri', not the separate component signs.

Not all epigraphists are equally reliable, and before publication of an important treatment of a text, scholars will often arrange to collate the published transcription against the actual tablet, to see if any signs, especially broken or damaged signs, should be represented differently.

Historiography

The key to reading logosyllabic cuneiform came from the Behistun inscription, a trilingual cuneiform inscription written in Old Persian, Elamite and Akkadian. (In a similar manner, the key to understanding Egyptian hieroglyphs was the bilingual (Greek and Egyptian with the Egyptian text in two scripts) Rosetta stone and Jean-François Champollion's transcription in 1822.)

In 1838 Henry Rawlinson, building on the 1802 work of Georg Friedrich Grotefend, was able to decipher the Old Persian section of the Behistun inscriptions, using his knowledge of modern Persian. When he recovered the rest of the text in 1843, he and others were gradually able to translate the Elamite and Akkadian sections of it, starting with the 37 signs he had deciphered for the Old Persian. Meanwhile, many more cuneiform texts were coming to light from archaeological excavations, mostly in the Semitic Akkadian language, which were duly deciphered.

By 1850, however, Edward Hincks came to suspect a non-Semitic origin for cuneiform. Semitic languages are structured according to consonantal forms, whereas cuneiform, when functioning phonetically, was a syllabary, binding consonants to particular vowels. Furthermore, no Semitic words could be found to explain the syllabic values given to particular signs.[38] Julius Oppert suggested that a non-Semitic language had preceded Akkadian in Mesopotamia, and that speakers of this language had developed the cuneiform script.

In 1855 Rawlinson announced the discovery of non-Semitic inscriptions at the southern Babylonian sites of Nippur, Larsa, and Uruk.

In 1856, Hincks argued that the untranslated language was agglutinative in character. The language was called "Scythic" by some, and, confusingly, "Akkadian" by others. In 1869, Oppert proposed the name "Sumerian", based on the known title "King of Sumer and Akkad", reasoning that if Akkad signified the Semitic portion of the kingdom, Sumer might describe the non-Semitic annex.

Credit for being first to scientifically treat a bilingual Sumerian-Akkadian text belongs to Paul Haupt, who published Die sumerischen Familiengesetze (The Sumerian family laws) in 1879.[39]

Ernest de Sarzec began excavating the Sumerian site of Tello (ancient Girsu, capital of the state of Lagash) in 1877, and published the first part of Découvertes en Chaldée with transcriptions of Sumerian tablets in 1884. The University of Pennsylvania began excavating Sumerian Nippur in 1888.

A Classified List of Sumerian Ideographs by R. Brünnow appeared in 1889.

The bewildering number and variety of phonetic values that signs could have in Sumerian led to a detour in understanding the language – a Paris-based orientalist, Joseph Halévy, argued from 1874 onward that Sumerian was not a natural language, but rather a secret code (a cryptolect), and for over a decade the leading Assyriologists battled over this issue. For a dozen years, starting in 1885, Friedrich Delitzsch accepted Halévy's arguments, not renouncing Halévy until 1897.[40]

François Thureau-Dangin working at the Louvre in Paris also made significant contributions to deciphering Sumerian with publications from 1898 to 1938, such as his 1905 publication of Les inscriptions de Sumer et d'Akkad. Charles Fossey at the Collège de France in Paris was another prolific and reliable scholar. His pioneering Contribution au Dictionnaire sumérien–assyrien, Paris 1905–1907, turns out to provide the foundation for P. Anton Deimel's 1934 Sumerisch-Akkadisches Glossar (vol. III of Deimel's 4-volume Sumerisches Lexikon).

In 1908, Stephen Herbert Langdon summarized the rapid expansion in knowledge of Sumerian and Akkadian vocabulary in the pages of Babyloniaca, a journal edited by Charles Virolleaud, in an article "Sumerian-Assyrian Vocabularies", which reviewed a valuable new book on rare logograms by Bruno Meissner.[41] Subsequent scholars have found Langdon's work, including his tablet transcriptions, to be not entirely reliable.

In 1944, the Sumerologist Samuel Noah Kramer provided a detailed and readable summary of the decipherment of Sumerian in his Sumerian Mythology.[42]

Friedrich Delitzsch published a learned Sumerian dictionary and grammar in the form of his Sumerisches Glossar and Grundzüge der sumerischen Grammatik, both appearing in 1914. Delitzsch's student, Arno Poebel, published a grammar with the same title, Grundzüge der sumerischen Grammatik, in 1923, and for 50 years it would be the standard for students studying Sumerian. Poebel's grammar was finally superseded in 1984 on the publication of The Sumerian Language: An Introduction to its History and Grammatical Structure, by Marie-Louise Thomsen. While much of Thomsen's understanding of Sumerian grammar would later be rejected by most or all Sumerologists, Thomsen's grammar (often with express mention of the critiques put forward by Pascal Attinger in his 1993 Eléments de linguistique sumérienne: La construction de du11/e/di 'dire') is the starting point of most recent academic discussions of Sumerian grammar.

More recent monograph-length grammars of Sumerian include Dietz-Otto Edzard's 2003 Sumerian Grammar and Bram Jagersma's 2010 A Descriptive Grammar of Sumerian (currently digital, but soon to be printed in revised form by Oxford University Press). Piotr Michalowski's essay (entitled, simply, "Sumerian") in the 2004 The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages has also been recognized as a good modern grammatical sketch.

There is relatively little consensus, even among reasonable Sumerologists, in comparison to the state of most modern or classical languages. Verbal morphology, in particular, is hotly disputed. In addition to the general grammars, there are many monographs and articles about particular areas of Sumerian grammar, without which a survey of the field could not be considered complete.

The primary institutional lexical effort in Sumerian is the Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary project, begun in 1974. In 2004, the PSD was released on the Web as the ePSD. The project is currently supervised by Steve Tinney. It has not been updated online since 2006, but Tinney and colleagues are working on a new edition of the ePSD, a working draft of which is available online.

Phonology

Assumed phonological or morphological forms will be between slashes //, with plain text used for the standard Assyriological transcription of Sumerian. Most of the following examples are unattested.

Phonemic inventory

Modern knowledge of Sumerian phonology is flawed and incomplete because of the lack of speakers, the transmission through the filter of Akkadian phonology and the difficulties posed by the cuneiform script. As I. M. Diakonoff observes, "when we try to find out the morphophonological structure of the Sumerian language, we must constantly bear in mind that we are not dealing with a language directly but are reconstructing it from a very imperfect mnemonic writing system which had not been basically aimed at the rendering of morphophonemics".[43]

Consonants

Sumerian is conjectured to have at least the following consonants:

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ŋ ⟨g̃⟩ | |||

| Plosive | plain | p ⟨b⟩ | t ⟨d⟩ | k ⟨g⟩ | ʔ[lower-alpha 1] | |

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨p⟩ | tʰ ⟨t⟩ | kʰ ⟨k⟩ | |||

| Fricative | s ⟨s⟩ | ʃ ⟨š⟩ | x ⟨ḫ~h⟩ | h[lower-alpha 1] | ||

| Affricate | plain | t͡s ⟨z⟩ | ||||

| aspirated | t͡sʰ ⟨ř~dr⟩ | |||||

| Tap | ɾ ⟨r⟩ | |||||

| Liquid | l ⟨l⟩ | |||||

| Semivowel | j[lower-alpha 1] | |||||

- a simple distribution of six stop consonants, in three places of articulation distinguished by aspiration, though later stages may have featured voicing:

- p (voiceless aspirated bilabial plosive),

- t (voiceless aspirated alveolar plosive),

- k (voiceless aspirated velar plosive),

- As a rule, /p/, /t/ and /k/ did not occur word-finally.[44]

- b (voiced unaspirated bilabial plosive),

- d (voiced unaspirated alveolar plosive),

- g (voiced unaspirated velar plosive).

- a phoneme usually represented by /ř/ (sometimes written dr) that was probably a voiceless aspirated alveolar affricate. This phoneme later became /d/ or /r/ in northern and southern dialects, respectively.

- a simple distribution of three nasal consonants in similar distribution to the stops:

- m (bilabial nasal),

- n (alveolar nasal),

- g̃ (frequently printed ĝ due to typesetting constraints, increasingly transcribed as ŋ) /ŋ/ (likely a velar nasal, as in sing, it has also been argued to be a labiovelar nasal [ŋʷ] or a nasalized labiovelar[45]).

- a set of three sibilants:

- s, likely a voiceless alveolar fricative,

- z, likely a voiceless unaspirated alveolar affricate, /t͡s/, as shown by Akkadian loans from /s/=[t͡s] to Sumerian /z/. In early Sumerian, this would have been the unaspirated counterpart to /ř/.[46]

- š (generally described as a voiceless postalveolar fricative, /ʃ/, as in ship)

- ḫ (a velar fricative, /x/, sometimes written h)

- two liquid consonants:

- l (a lateral consonant)

- r (a rhotic consonant)

The existence of various other consonants has been hypothesized based on graphic alternations and loans, though none have found wide acceptance. For example, Diakonoff lists evidence for two l-sounds, two r-sounds, two h-sounds, and two g-sounds (excluding the velar nasal), and assumes a phonemic difference between consonants that are dropped word-finally (such as the g in zag > za3) and consonants that remain (such as the g in lag). Other "hidden" consonant phonemes that have been suggested include semivowels such as /j/ and /w/,[47] and a glottal fricative /h/ or a glottal stop that could explain the absence of vowel contraction in some words[48]—though objections have been raised against that as well.[49] A recent descriptive grammar by Bram Jagersma includes /j/, /h/, and /ʔ/ as unwritten consonants, with the glottal stop even serving as the first-person pronominal prefix.[50]

Very often, a word-final consonant was not expressed in writing—and was possibly omitted in pronunciation—so it surfaced only when followed by a vowel: for example the /k/ of the genitive case ending -ak does not appear in e2 lugal-la "the king's house", but it becomes obvious in e2 lugal-la-kam "(it) is the king's house" (compare liaison in French).

Vowels

The vowels that are clearly distinguished by the cuneiform script are /a/, /e/, /i/, and /u/. Various researchers have posited the existence of more vowel phonemes such as /o/ and even /ɛ/ and /ɔ/, which would have been concealed by the transmission through Akkadian, as that language does not distinguish them.[51][52] That would explain the seeming existence of numerous homophones in transliterated Sumerian, as well as some details of the phenomena mentioned in the next paragraph.[53] These hypotheses are not yet generally accepted.[45]

There is some evidence for vowel harmony according to vowel height or advanced tongue root in the prefix i3/e- in inscriptions from pre-Sargonic Lagash,[51] and perhaps even more than one vowel harmony rule.[54][52] There also appear to be many cases of partial or complete assimilation of the vowel of certain prefixes and suffixes to one in the adjacent syllable reflected in writing in some of the later periods, and there is a noticeable, albeit not absolute, tendency for disyllabic stems to have the same vowel in both syllables.[55] These patterns, too, are interpreted as evidence for a richer vowel inventory by some researchers.[51][52] What appears to be vowel contraction in hiatus (*/aa/, */ia/, */ua/ > a, */ae/ > a, */ue/ > u, etc.) is also very common.

Syllables could have any of the following structures: V, CV, VC, CVC. More complex syllables, if Sumerian had them, are not expressed as such by the cuneiform script.

Grammar

Ever since its decipherment, research of Sumerian has been made difficult not only by the lack of any native speakers, but also by the relative sparseness of linguistic data, the apparent lack of a closely related language, and the features of the writing system. Typologically, as mentioned above, Sumerian is classified as an agglutinative, split ergative, and subject-object-verb language. It behaves as a nominative–accusative language in the 1st and 2nd persons of the incomplete tense-aspect, but as ergative–absolutive in most other forms of the indicative mood. Sumerian nouns are organized in two grammatical genders based on animacy: animate and inanimate. Animate nouns include humans, gods, and in some instances the word for "statue". Case is indicated by suffixes on the noun. Noun phrases are right branching with adjectives and modifiers following nouns.[56]

Sumerian verbs have a tense-aspect complex, contrasting complete and incomplete actions/states. The two have different conjugations and many have different roots. Verbs also mark mood, voice, polarity, iterativity, and intensity; and agree with subjects and objects in number, person, animacy, and case. Sumerian moods are: indicative, imperative, cohortative, precative/affirmative, prospective aspect/cohortative mood, affirmative/negative-volitive, unrealised-volitive?, negative?, affirmative?, polarative, and are marked by a verbal prefix. The prefixes appear to conflate mood, aspect, and polarity; and their meanings are also affected by the tense-aspect complex. Sumerian voices are: active, and middle or passive. Verbs are marked for three persons: 1st, 2nd, 3rd; in two numbers: singular and plural. Finite verbs have three classes of prefixes: modal prefixes, conjugational prefixes, and pronominal/dimensional prefixes. Modal prefixes confer the above moods on the verb. Conjugational prefixes are thought to confer perhaps venitive/andative, being/action, focus, valency, or voice distinctions on the verb. Pronominal/dimensional prefixes correspond to noun phrases and their cases. Non-finite verbs include participles and relative clause verbs, both formed through nominalisation. Finite verbs take prefixes and suffixes, non-finite verbs only take suffixes. Verbal roots are mostly monosyllabic, though verbal root duplication and suppletion can also occur to indicate plurality. Root duplication can also indicate iterativity or intensity of the verb.[57]

Noun phrases

The Sumerian noun is typically a one or two-syllable root (igi "eye", e2 "house, household", nin "lady"), although there are also some roots with three syllables like šakanka "market". There are two grammatical genders, usually called human and non-human (the first includes gods and the word for "statue" in some instances, but not plants or animals, the latter also includes collective plural nouns), whose assignment is semantically predictable.

The adjectives and other modifiers follow the noun (lugal maḫ "great king"). The noun itself is not inflected; rather, grammatical markers attach to the noun phrase as a whole, in a certain order. Typically, that order would be:

| noun | adjective | numeral | genitive phrase | relative clause | possessive marker | plural marker | case marker |

|---|

An example may be /dig̃ir gal-gal-g̃u-ne-ra/ ("god great (reduplicated)-my-plural-dative" = "for all my great gods").[58] The possessive, plural and case markers are traditionally referred to as "suffixes", but have recently also been described as enclitics[59] or postpositions.[60]

The plural markers are /-(e)ne/ (optional) for nouns of the human gender. Non-human nouns are not marked by a plural suffix. However, plurality can also be expressed with the adjective ḫi-a "various", with the plural of the copula /-meš/, by reduplication of the noun (kur-kur "all foreign lands") or of the following adjective (a gal-gal "all the great waters") (reduplication is believed to signify totality) or by the plurality of only the verb form. Plural reference in the verb form occurs only for human nouns.

The generally recognised case markers are:

| case | ending |

|---|---|

| absolutive | /-Ø/ |

| ergative | /-e/ (only with animates) |

| allative | /-e/ (only with inanimates) |

| genitive | /-ak/[lower-alpha 2] |

| equative | /-gin/ |

| dative | /-r(a)/ |

| terminative | /-(e)š(e)/ |

| comitative | /-da/ |

| locative | /-a/ |

| ablative | /-ta/[lower-alpha 3] |

More endings are recognised by some researchers; e.g. Bram Jagersma notes a separate adverbiative case in /-eš/ and a second locative used mostly with infinite verb forms.[61]

Additional spatial or temporal meanings can be expressed by genitive phrases like "at the head of" = "above", "at the face of" = "in front of", "at the outer side of" = "because of" etc.: bar udu ḫad2-ak-a = "outer.side sheep white-genitive-locative" = "in the outer side of a white sheep" = "because of a white sheep".

The embedded structure of the noun phrase can be further illustrated with the phrase sipad udu siki-ak-ak-ene ("the shepherds of woolly sheep"), where the first genitive morpheme (-a(k)) subordinates siki "wool" to udu "sheep", and the second subordinates udu siki-a(k) "sheep of wool" (or "woolly sheep") to sipad "shepherd".[62]

Pronouns

The attested personal pronouns are:

| independent | possessive suffix/enclitic | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person singular | g̃e26-e | -g̃u10 |

| 2nd person singular | ze2-e | -zu |

| 3rd person singular animate | a-ne or e-ne | -(a)-n(i) |

| 3rd person singular inanimate | -b(i) | |

| 1st person plural | -me | |

| 2nd person plural | -zu-ne-ne | |

| 3rd person plural animate | a/e-ne-ne | -b(i) |

| 3rd person plural inanimate | -b(i) |

For most of the suffixes, vowels are subject to loss if they are attached to vowel-final words.

Numerals

Sumerian has a combination decimal and sexagesimal system (for example, 600 is 'ten sixties'), so that the Sumerian lexical numeral system is sexagesimal with 10 as a subbase.[63] Numerals and composite numbers are as follows:

| number | name | explanation notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | diš, deš,[64] dili | |

| 2 | min, mina[65] | |

| 3 | eš[66] | |

| 4 | limmu, lím[67] | |

| 5 | ia, í[68] | |

| 6 | aš[69] | ía 'five' + aš 'one' |

| 7 | imin[70] | |

| 8 | ussu[71] | |

| 9 | ilimmu[70] | ía/í (5) + limmu (4) |

| 10 | u, hà, hù, a, u[68] | |

| 11 | u-diš (?) | |

| 20 | niš | |

| 30 | ušu | |

| 40 | nimin | 'less two [tens]' |

| 50 | ninnu | 'less ten' |

| 60 | g̃iš(d), g̃eš(d)[72] | |

| 600 | g̃eš(d)u | ten g̃eš(d) |

| 1000 | lim | |

| 3600 | šar |

General

The Sumerian finite verb distinguishes a number of moods and agrees (more or less consistently) with the subject and the object in person, number and gender. The verb chain may also incorporate pronominal references to the verb's other modifiers, which has also traditionally been described as "agreement", although, in fact, such a reference and the presence of an actual modifier in the clause need not co-occur: not only e2-še3 ib2-ši-du-un "I'm going to the house", but also e2-še3 i3-du-un "I'm going to the house" and simply ib2-ši-du-un "I'm going to it" are possible.[60]

The Sumerian verb also makes a binary distinction according to a category that some regard as tense (past vs present-future), others as aspect (perfective vs imperfective), and that will be designated as TA (tense/aspect) in the following. The two members of the opposition entail different conjugation patterns and, at least for many verbs, different stems; they are theory-neutrally referred to with the Akkadian grammatical terms for the two respective forms – ḫamṭu (quick) and marû (slow, fat). Finally, opinions differ on whether the verb has a passive or a middle voice and how it is expressed.

The verbal root is almost always a monosyllable and, together with various affixes, forms a so-called verbal chain which is described as a sequence of about 15 slots, though the precise models differ.[73] The finite verb has both prefixes and suffixes, while the non-finite verb may only have suffixes. Broadly, the prefixes have been divided in three groups that occur in the following order: modal prefixes, "conjugation prefixes", and pronominal and dimensional prefixes.[74] The suffixes are a future or imperfective marker /-ed-/, pronominal suffixes, and an /-a/ ending that nominalizes the whole verb chain. The overall structure can be summarized as follows:

| slot | modal prefix | conjugation prefix | pronominal prefix | dimensional prefix | pronominal prefix | stem | future/imperfective | pronominal suffix | nominalizer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| common

morphemes |

Ø-, ḫa-, u-, ga- |

mu-, i- (e-,a-), ba-, bi- |

-Ø-, -e-/r-, -n-, -b- |

-a-, -da-, -ta-, |

-Ø-, -e-/r-, -n-, -b- |

-e(d)- | -en -en -Ø, -e -enden |

-a |

Note also that more than one pairing of a pronominal prefix and a dimensional prefix may occur within the verb chain.

Modal prefixes

The modal prefixes are :

- /Ø-/ (indicative),

- /nu-/ and /la-/, /li-/ (negative; /la/ and /li/ are used before the conjugation prefixes ba- and bi2-),

- /ga-/ (cohortative, "let me/us"),

- /ḫa-/ or /ḫe-/ with further assimilation of the vowel in later periods (precative or affirmative),

- /u-/ (prospective "after/when/if", also used as a mild imperative),

- /na-/ (negative or affirmative),

- /bara-/ (negative or vetitive),

- /nuš-/ (unrealizable wish?) and

- /ša-/ with further assimilation of the vowel in later periods (affirmative?).

Their meaning can depend on the TA.

"Conjugation prefixes"

The meaning, structure, identity and even the number of "conjugation prefixes" have always been a subject of disagreements. The term "conjugation prefix" simply alludes to the fact that a finite verb in the indicative mood must always contain one of them. Some of their most frequent expressions in writing are mu-, i3- (ED Lagaš variant: e-), ba-, bi2- (ED Lagaš: bi- or be2), im-, im-ma- (ED Lagaš e-ma-), im-mi- (ED Lagaš i3-mi or e-me-), mi- (always followed by pronominal-dimensional -ni-) and al-, and to a lesser extent a-, am3-, am3-ma-, and am3-mi-; virtually all analyses attempt to describe many of the above as combinations or allomorphs of each other.

The starting point of most analyses are the obvious facts that the 1st person dative always requires mu-, and that the verb in a "passive" clause without an overt agent tends to have ba-. Proposed explanations usually revolve around the subtleties of spatial grammar, information structure (focus[75]), verb valency, and, most recently, voice.[76] Mu-, im- and am3- have been described as ventive morphemes, while ba- and bi2- are sometimes analyzed as actually belonging to the pronominal-dimensional group (inanimate pronominal /-b-/ + dative /-a-/ or directive /-i-/).[77] Im-ma-, im-mi-, am3-ma- and am3-mi- are then considered by some as a combination of the ventive and /ba-/, /bi-/[77] or otherwise a variety of the ventive.[78] The element i3- has been argued to be a mere prothetic vowel, al- a stative prefix, ba- a middle voice prefix, etcetera.

Pronominal and dimensional prefixes

The dimensional prefixes of the verb chain basically correspond to, and often repeat, the case markers of the noun phrase. Like the latter, they are attached to a "head" – a pronominal prefix. The other place where a pronominal prefix can be placed is immediately before the stem, where it can have a different allomorph and expresses the absolutive or the ergative participant (the transitive subject, the intransitive subject or the direct object), depending on the TA and other factors, as explained below. However, this neat system is obscured by the tendency to drop or merge many of the prefixes in writing and possibly in pronunciation as well.

The generally recognized dimensional prefixes are shown in the table below; if several occur within the same verb complex, they are placed in the order they are listed in.

| dative | comitative | ablative | terminative | directive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /-a-/?[lower-alpha 4] | -da- | -ta- | -ši- (early -še3-) | /-i-/? |

The pronominal prefixes are:

| prefix | Notes | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person singular | -Ø-?, -e-? | Sometimes thought to represent a glottal stop /ʔ/ (so Zólyomi, e.g. 2017, and Jagersma, e.g. 2009). |

| 2nd person singular | -e-, -r- | |

| 3rd person singular animate | -n- | |

| 3rd person singular inanimate | -b- | |

| 1st person plural | -me- | For a subject or object (immediately before the stem), the singular is used instead. |

| 2nd person plural | -re-? | |

| 3rd person plural | -ne- |

The morphemes /-n-/ and /-b-/ are clearly the prefixes for the 3rd person singular animate and inanimate respectively; the 2nd person singular appears as -e- in most contexts, but as /-r-/ before the dative (-ra-), leading some[79] to assume a phonetic /-ir-/ or /-jr-/. The 1st person may appear as -e-, too, but is more commonly not expressed at all (the same may frequently apply to 3rd and 2nd persons); it is, however, cued by the choice of mu- as conjugation prefix[78] (/mu-/ + /-a-/ → ma-). The 1st, 2nd and 3rd plural infixes are -me-, -re?- and -ne- in the dative[78] and perhaps in other contexts as well,[79] though not in the pre-stem position (see below).

An additional exception from the system is the prefix -ni- which corresponds to a noun phrase in the locative – in which case it doesn't seem to be preceded by a pronominal prefix – and, according to Gábor Zólyomi and others, to an animate one in the directive – in the latter case it is analyzed as pronominal /-n-/ + directive /-i-/. Zólyomi and others also believe that special meanings can be expressed by combinations of non-identical noun case and verb prefix.[80] Also according to some researchers[81] /-ni-/ and /bi-/ acquire the forms /-n-/ and /-b-/ (coinciding with the absolutive–ergative pronominal prefixes) before the stem if there isn't already an absolutive–ergative pronominal prefix in pre-stem position: mu-un-kur9 = /mu-ni-kur/ "he went in there" (as opposed to mu-ni-kur9 = mu-ni-in-kur9 = /mu-ni-n-kur/ "he brought in – caused [something or someone] to go in – there".

Pronominal suffixes and conjugation

The pronominal suffixes are as follows:

| marû | ḫamṭu | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person singular | /-en/ | |

| 2nd person singular | /-en/ | |

| 3rd person singular | /-e/ | /-Ø/ |

| 1st person plural | /-enden/ | |

| 2nd person plural | /-enzen/ | |

| 3rd person plural | /-ene/ | /-eš/ |

The initial vowel in all of the above suffixes can be assimilated to the root.

The general principle for pronominal agreement in conjugation is that in ḫamṭu TA, the transitive subject is expressed by the prefix, and the direct object by the suffix, and in the marû TA it is the other way round; as for the intransitive subject, it is expressed, in both TAs, by the suffixes and is thus treated like the object in ḫamṭu and like the subject in marû (except that its third person is expressed, not only in ḫamṭu but also in marû, by the suffixes used for the object in the ḫamṭu TA). A major exception from this generalization are the plural forms – in them, not only the prefix (as in the singular), but also the suffix expresses the transitive subject.

Additionally, the prefixes of the plural are identical to those of the singular – /-?-/ or /-e-/, /-e-/, /-n-/, /-b-/ – as opposed to the -me-, -re-?, -ne- that are presumed for non-pre-stem position – and some scholars believe that the prefixes of the 1st and second person are /-en-/ rather than /-e-/ when they stand for the object.[82] Before the pronominal suffixes, a suffix /-e(d)-/ with a future or related modal meaning can be inserted, accounting for occurrences of -e in the third-person singular marû of intransitive forms; because of its meaning, it can also be said to signal marû in these forms.[79]

The use of the personal affixes in conjugation can be summarised as follows:

| ḫamṭu | marû | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct object | Intransitive subject | Transitive subject | Direct object | Intransitive subject | Transitive subject | |

| 1st sing | ...-en | ...-en | -Ø/-e-... | -Ø/-e-... | ...-en | ...-en |

| 2nd sing | ...-en | ...-en | -e-... | -e-... | ...-en | ...-en |

| 3rd sing

animate |

...-Ø | ...-Ø | -n-... | -n-... | ...-Ø | ...-e |

| 3rd sing inanimate | ...-Ø | ...-Ø | -b-... | -b-... | ...-Ø | ...-e |

| 1st pl | ...-enden | ...-enden | -Ø/e-...-enden | -Ø/-e-...? | ...-enden | ...-enden |

| 2nd pl | ...-enzen | ...-enzen | -e-...-enzen | -e-...? | ...-enzen | ...-enzen |

| 3rd pl (animates only) | ...-eš | ...-eš | -n-...-eš | -ne-...? | ...-eš | ...-ene |

Examples for TA and pronominal agreement: (ḫamṭu is rendered with past tense, marû with present): /i-gub-en/ ("I stood" or "I stand"), /i-n-gub-en/ ("he placed me" or "I place him"); /i-sug-enden/ ("we stood/stand"); /i-n-dim-enden/ ("he created us" or "we create him"); /mu-e?-dim-enden/ ("we created [someone or something]"); i3-gub-be2 = /i-gub-ed/ ("he will/must stand"); ib2-gub-be2 = /i-b-gub-e/ ("he places it"); /i-b-dim-ene/ ("they create it"), /i-n-dim-eš/ ("they created [someone or something]" or "he created them"), /i-sug-eš/ ("they stood" or "they stand").

Confusingly, the subject and object prefixes (/-n-/, /-b-/, /-e-/) are not commonly spelled out in early texts, although the "full" spellings do become more usual during the Third Dynasty of Ur (in the Neo-Sumerian period) and especially during the Late Sumerian period. Thus, in earlier texts, one finds mu-ak and i3-ak (e-ak in early dynastic Lagash) instead of mu-un-ak and in-ak for /mu-n-ak/ and /i-n-ak/ "he/she made", and also mu-ak instead of mu-e-ak "you made". Similarly, pre-Ur III texts also spell the first- and second-person suffix /-en/ as -e, making it coincide with the third person in the marû form.

Stem

The verbal stem itself can also express grammatical distinctions. The plurality of the absolutive participant[78] can be expressed by complete reduplication of the stem or by a suppletive stem. Reduplication can also express "plurality of the action itself",[78] intensity or iterativity.[47]

With respect to TA marking, verbs are divided in four types; ḫamṭu is always the unmarked TA.

- The stems of the 1st type, regular verbs, do not express TA at all according to most scholars, or, according to M. Yoshikawa and others, express marû TA by adding an (assimilating) /-e-/ as in gub-be2 or gub-bu vs gub (which is, however, nowhere distinguishable from the first vowel of the pronominal suffixes except for intransitive marû 3rd person singular).

- The 2nd type express marû by partial reduplication of the stem, e.g. kur9 vs ku4-ku4.

- The 3rd type express marû by adding a consonant, e.g. te vs teg̃3.

- The 4th type use a suppletive stem, e.g. dug4 vs e. Thus, as many as four different suppletive stems can exist, as in the admittedly extreme case of the verb "to go": g̃en ("to go", ḫamṭu sing.), du (marû sing.), (e-)re7 (ḫamṭu plur.), sub2 (marû plur.)

Other issues

The nominalizing suffix /-a/ converts non-finite and finite verbs into participles and relative clauses: šum-ma "given",[83][lower-alpha 5] mu-na-an-šum-ma "which he gave to him", "who gave (something) to him", etc.. Adding /-a/ after the future/modal suffix /-ed/ produces a form with a meaning similar to the Latin gerundive: šum-mu-da = "which will/should be given". On the other hand, adding a (locative-terminative?) /-e/ after the /-ed/ yields a form with a meaning similar to the Latin ad + gerund (acc.) construction: šum-mu-de3 = "(in order) to give".

The copula verb /me/ "to be" is mostly used as an enclitic: -men, -men, -am, -menden, -menzen, -(a)meš.

The imperative mood construction is produced with a singular ḫamṭu stem, but using the marû agreement pattern, by turning all prefixes into suffixes: mu-na-an-sum "he gave (something) to him", mu-na-e-sum-mu-un-ze2-en "you (plur.) gave (something) to him" – sum-mu-na-ab "give it to him!", sum-mu-na-ab-ze2-en "give (plur.) it to him!" Compare the French vous le lui donnez, but donnez-le-lui![78]

Syntax

The basic word order is subject–object–verb; verb finality is only violated in rare instances, in poetry. The moving of a constituent towards the beginning of the phrase may be a way to highlight it,[84] as may the addition of the copula to it. The so-called anticipatory genitive (e2-a lugal-bi "the owner of the house/temple", lit. "of the house, its owner") is common and may signal the possessor's topicality.[84] There are various ways to express subordination, some of which have already been hinted at; they include the nominalization of a verb, which can then be followed by case morphemes and possessive pronouns (kur9-ra-ni "when he entered"[lower-alpha 6]) and included in "prepositional" constructions (eg̃er a-ma-ru ba-ur3-ra-ta "back – flood – conjugation prefix – sweep over – nominalizing suffix – [genitive suffix?] – ablative suffix" = "from the back of the Flood's sweeping-over" = "after the Flood had swept over"). Subordinating conjunctions such as ud-da "when, if", tukum-bi "if" are also used, though the coordinating conjunction u3 "and", a Semitic adoption, is rarely used. A specific problem of Sumerian syntax is posed by the numerous so-called compound verbs, which usually involve a noun immediately before the verb, forming a lexical or idiomatic unit[85] (e.g. šu...ti, lit. "hand-approach" = "receive"; igi...du8, lit. "eye-open" = "see"). Some of them are claimed to have a special agreement pattern that they share with causative constructions: their logical object, like the causee, receives, in the verb, the directive infix, but in the noun, the dative suffix if animate and the directive if inanimate.[80]

Sample text

Inscription by Entemena of Lagaš

This text was inscribed on a small clay cone c. 2400 BC. It recounts the beginning of a war between the city-states of Lagaš and Umma during the Early Dynastic III period, one of the earliest border conflicts recorded. (RIME 1.09.05.01)[86]

𒀭𒂗𒆤

den-lil2

𒈗

lugal

𒆳𒆳𒊏

kur-kur-ra

𒀊𒁀

ab-ba

𒀭𒀭𒌷𒉈𒆤

dig̃ir-dig̃ir-re2-ne-ke4

𒅗

inim

𒄀𒈾𒉌𒋫

gi-na-ni-ta

𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄈𒋢

dnin-g̃ir2-su

𒀭𒇋𒁉

dšara2-bi

𒆠

ki

𒂊𒉈𒋩

e-ne-sur

"Enlil, king of all the lands, father of all the gods, by his firm command, fixed the border between Ningirsu and Šara."

𒈨𒁲

me-silim

𒈗

lugal

𒆧𒆠𒆤

kiški-ke4

𒅗

inim

𒀭𒅗𒁲𒈾𒋫

dištaran-na-ta

𒂠

eš2

𒃷

gana2

𒁉𒊏

be2-ra

𒆠𒁀

ki-ba

𒈾

na

𒉈𒆕

bi2-ru2

"Mesilim, king of Kiš, at the command of Ištaran, measured the field and set up a stele there."

𒍑

uš

𒉺𒋼𒋛

ensi2

𒄑𒆵𒆠𒆤

ummaki-ke4

𒉆

nam

𒅗𒈠

inim-ma

𒋛𒀀𒋛𒀀𒂠

diri-diri-še3

𒂊𒀝

e-ak

"Ush, ruler of Umma, acted unspeakably."

𒈾𒆕𒀀𒁉

na-ru2-a-bi

𒉌𒉻

i3-pad

𒂔

edin

𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠𒂠

lagaški-še3

𒉌𒁺

i3-g̃en

"He ripped out that stele and marched toward the plain of Lagaš."

𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄈𒋢

dnin-g̃ir2-su

𒌨𒊕

ur-sag

𒀭𒂗𒆤𒇲𒆤

den-lil2-la2-ke4

𒅗

inim

𒋛𒁲𒉌𒋫

si-sa2-ni-ta

𒄑𒆵𒆠𒁕

ummaki-da

𒁮𒄩𒊏

dam-ḫa-ra

𒂊𒁕𒀝

e-da-ak

"Ningirsu, warrior of Enlil, at his just command, made war with Umma."

𒅗

inim

𒀭𒂗𒆤𒇲𒋫

den-lil2-la2-ta

𒊓

sa

𒌋

šu4

𒃲

gal

𒉈𒌋

bi2-šu4

𒅖𒇯𒋺𒁉

SAḪAR.DU6.TAKA4-bi

𒂔𒈾

eden-na

𒆠

ki

𒁀𒉌𒍑𒍑

ba-ni-us2-us2

"At Enlil's command, he threw his great battle net over it and heaped up burial mounds for it on the plain."

𒂍𒀭𒈾𒁺

e2-an-na-tum2

𒉺𒋼𒋛

ensi2

𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠

lagaški

𒉺𒄑𒉋𒂵

pa-bil3-ga

𒂗𒋼𒈨𒈾

en-mete-na

𒉺𒋼𒋛

ensi2

𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠𒅗𒆤

lagaški-ka-ke4

"Eannatum, ruler of Lagash, uncle of Entemena, ruler of Lagaš"

𒂗𒀉𒆗𒇷

en-a2-kal-le

𒉺𒋼𒋛

ensi2

𒄑𒆵𒆠𒁕

ummaki-da

𒆠

ki

𒂊𒁕𒋩

e-da-sur

"fixed the border with Enakale, ruler of Umma"

See also

- List of extinct languages of Asia

- List of languages by first written accounts

- Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary

- Sumerian literature

References

- Notes

- Not usually transcribed

- In some cases k is omitted. For example as in "e2 lugal-la (The house of the king, originally it should be e2-lugal-ak but because of auslaut and k omission, it turned into e2 lugal-la)". However k reappears if another grammatical marker is added as in "e2 lugal-la-ke-ne (with the plural marker -ene)"

- The naming and number of cases vary according to differing analyses of Sumerian linguistics.

- But apparently -e in the plural, see below.

- The reduplication of the consonants m in this example is an auslaut. Find more info in this link #

- A newer interpretation is that the last syllable in such examples is to be read -ne, i.e. 3rd person possessive -ni plus directive -e. In contrast, in the 1st and 2nd persons, we find this apparent -ni attached to 1st and 2nd person pronouns (zig-a-g̃u-ni 'as I rose'), which leads Jagersma to interpret it as an otherwise obsolete locative ending: lit. 'at my rising' (Jagersma 2009: 672-674).

- Prince 1914, p. 74.

- Prince 1908, p. xvii.

- Delitzsch 1914, p. 60-62.

- Langdon 1911, p. 117.

- Prince 1908, p. xvii-xviii.

- Numbers 1-12; table after J.D. Prince,[lower-alpha 7] who said: "Delitzsch gives the Sumerian numerals (pp. 60-62) somewhat differently from Langdon (p. 117) and MSL (pp. xvii-xviii), as shown in the following comparative table:"[lower-alpha 8]

Delitzsch[lower-alpha 9] Langdon[lower-alpha 10] MSL[lower-alpha 11] as, ge, din, dilli aš diš mina, min min, man man, min, dab, tab eš eššu eš, iš limmu lammu limmu ia ia ia aš ašša aš umun, imin imin iminna ussu ussu us ilimmu elimmu ilim u, ģa; a, ģa u u neš, niš niš niš usu usu usu, es, is

- Citations

- "What Are the Oldest Languages in the World Still Widely Spoken Today?". Mondly Blog. 2020-05-13. Retrieved 2022-07-09.

- Woods C. 2006 "Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian". In S. L. Sanders (ed) Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture: 91–120 Chicago.

- Joan Oates (1979). Babylon [Revised Edition] Thames and Hudston, Ltd. 1986 p. 30, 52–53.

- The A.K. Grayson, Penguin Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations, ed. Arthur Cotterell, Penguin Books Ltd. 1980. p. 92

- THUREAU-DANGIN, F. (1911). "Notes Assyriologiques". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 8 (3): 138–141. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23284567.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Sumerian Language[Usurped!]

- Michalowski, P., 2006: "The Lives of the Sumerian Language", in S.L. Sanders (ed.), Margins of Writing, Origins of Cultures, Chicago, 159–184

- Eleanor Robson, Information Flows in Rural Babylonia c. 1500 BC, in C. Johnston (ed.), The Concept of the Book: the Production, Progression and Dissemination of Information, London: Institute of English Studies/School of Advanced Study, January 2019 ISBN 9780992725747

- Sylvain Auroux (2000). History of the Language Sciences. Vol. 1. p. 2. ISBN 9783110194005.

- Hartmann, Henrike (1960). Die Musik der Sumerischen Kultur. p. 138.

- Rubio (2007). Morphology of Asia and Africa. p. 1370. ISBN 9781575061092.

- Piotr Michalowski, "Sumerian," The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages." Ed. Roger D. Woodard (2004, Cambridge University Press). Pages 19–59

- Georges Roŭ (1993). Ancient Iraq (3rd ed.). London: Penguin Books. p. 80-82.

- Joan Oates (1986). Babylon (Rev. ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. p. 19.

- John Haywood (2005). The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Civilizations. London: Penguin Books. p. 28.

- Piotr Michalowski, "Sumerian," The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages (2004, Cambridge), pg. 22

- Dewart, Leslie (1989). Evolution and Consciousness: The Role of Speech in the Origin and Development of Human Nature. p. 260.

- "unige.ch" (in French). 16 November 2006.

- "inrp.fr" (in French).

- DIAKONOFF, Igor M. (1997). "External Connections of the Sumerian Language". Mother Tongue. 3: 54–63.

- Sathasivam, A (2017). Proto-Sumero-Dravidian : The Common Origin of Sumerian and Dravidian Languages. Kingston, UK: History and Heritage Unit, Tamil Information Centre. ISBN 9781852010249.

- Simo Parpola (July 23, 2007). "Sumerian: A Uralic language". Language in the Ancient Near East. Compte rendu de la 53e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Moscow. (work in process)

- Gostony, C. G. 1975: Dictionnaire d'étymologie sumérienne et grammaire comparée. Paris.

- Zakar, András (1971). "Sumerian – Ural-Altaic affinities". Current Anthropology. 12 (2): 215–225. doi:10.1086/201193. JSTOR 2740574. S2CID 143879460..

- Aleksi Sahala 2009–2012. "Sumero-Indo-European Language Contacts" (PDF). – University of Helsinki.

- Bobula, Ida (1951). Sumerian affiliations. A Plea for Reconsideration. Washington D.C. (Mimeographed ms.)

- Bomhard, Allan R. & PJ Hopper (1984). Toward Proto-Nostratic: a new approach to the comparison of Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Afroasiatic. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory.

- Jan Braun (2004). "SUMERIAN AND TIBETO-BURMAN, Additional Studies". Wydawnictwo Agade. Warszawa. ISBN 83-87111-32-5..

- Yurii Mosenkis. "Austro-Asiatic Elamite and Tibeto-Burman Sumerian: the traces of the Eurasian Supermacrofamily Homeland in West Asia?".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Ruhlen, Merritt (1994). The Origin of Language: Tracing the Evolution of the Mother Tongue. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 143.

- Høyrup, Jens (1998). "Sumerian: The descendant of a proto-historical creole? An alternative approach to the Sumerian problem". Published: AIΩN. Annali del Dipartimento di Studi del Mondo Classico e del Mediterraneo Antico. Sezione linguistica. Istituto Universitario Orientale, Napoli. 14 (1992, publ. 1994): 21–72, Figs. 1–3.

- Rubio, Gonzalo (1999). "On the alleged 'pre-Sumerian substratum'". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 51 (1999): 1–16. doi:10.2307/1359726. JSTOR 1359726. S2CID 163985956.

- Whittaker, Gordon (2008). "The Case for Euphratic" (PDF). Bulletin of the Georgian National Academy of Sciences. Tbilisi. 2 (3): 156–168. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- Edzard, Dietz Otto, "Wann ist Sumerisch als gesprochene Sprache ausgestorben?", Acta Sumerologica 22, pp. 53-70, 2000

- Krejci, Jaroslav (1990). Before the European Challenge: The Great Civilizations of Asia and the Middle East. SUNY Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7914-0168-2.

- Mémoires. Mission archéologique en Iran. 1900. p. 53.

- Kevin J. Cathcart, "The Earliest Contributions to the Decipherment of Sumerian and Akkadian", Cuneiform Digital Library Journal, 2011

- In Keilschrift, Transcription und Übersetzung : nebst ausführlichem Commentar und zahlreichen Excursen : eine assyriologische Studie (Leipzig : J.C. Hinrichs, 1879)

- Hommel, Fritz. "The Sumerian Language and Its Affinities.", The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 18, no. 3, 1886, pp. 351–63

- "Sumerian-Assyrian Vocabularies".

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961) [1944]. Sumerian Mythology.

- Diakonoff 1976:112

- [Keetman, J. 2007. "Gab es ein h im Sumerischen?" In: Babel und Bibel 3, p.21]

- Michalowski, Piotr (2008): "Sumerian". In: Woodard, Roger D. (ed.) The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Aksum. Cambridge University Press. P.16

- Jagersma, Bram (January 2000). "Sound change in Sumerian: the so-called /dr/-phoneme". Acta Sumerologica 22: 81-87. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- "Sumerian language". The ETCSL project. Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford. 2005-03-29. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- Attinger, Pascal, 1993. Eléments de linguistique sumérienne. p. 212 ()

- [Keetman, J. 2007. "Gab es ein h im Sumerischen?" In: Babel und Bibel 3, passim]

- Jagersma, Abraham Hendrik (4 November 2010). A descriptive grammar of Sumerian. openaccess.leidenuniv.nl (Thesis). pp. 33, 388. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- Smith, Eric J M. 2007. [-ATR] "Harmony and the Vowel Inventory of Sumerian". Journal of Cuneiform Studies, volume 57

- Keetman, J. 2013. "Die sumerische Wurzelharmonie". Babel und Bibel 7 p.109-154

- "Zólyomi, Gábor. 2016. An introduction to the grammar of Sumerian. P. 12-13" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-16. Retrieved 2018-09-16.

- Keetman, J. 2009. "The limits of [ATR] vowel harmony in Sumerian and some remarks about the need of transparent data". Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires 2009, No. 65

- Michalowski, Piotr (2008): "Sumerian". In: Woodard, Roger D. (ed.) The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Aksum. Cambridge University Press. P.17

- Gábor Zólyomi: An Introduction to the Grammar of Sumerian Open Access textbook, Budapest 2017

- Introduction to Sumerian grammar by Daniel A. Foxvog at CDLI

- Kausen, Ernst. 2006. Sumerische Sprache. p.9

- Zólyomi, Gábor, 1993: Voice and Topicalization in Sumerian. PhD Dissertation

- Johnson, Cale, 2004: In the Eye of the Beholder: Quantificational, Pragmatic and Aspectual Features of the *bí- Verbal Formation in Sumerian, Dissertation. UCLA, Los Angeles Archived 2013-06-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Jagersma (2010: 137)

- Zólyomi, Gábor (2014). Grzegorek, Katarzyna; Borowska, Anna; Kirk, Allison (eds.). Copular Clauses and Focus Marking in Sumerian. De Gruyter. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-11-040169-1. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Stephen Chrisomalis (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge University Press. p. 236. ISBN 9780521878180. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- Halloran pdf 1999, p. 46.

- Halloran pdf 1999, p. 37.

- Halloran pdf 1999, p. 8.

- Halloran pdf 1999, p. 35.

- Halloran pdf 1999, p. 11.

- Halloran pdf 1999.

- Halloran pdf 1999, p. 59.

- Halloran pdf 1999, p. 20.

- Jagersma (2010: 244)

- See e.g. Rubio 2007, Attinger 1993, Zólyomi 2005 ("Sumerisch". In: Sprachen des Alten Orients, ed. M. Streck), PPCS Morphological model Archived October 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- E.g. Attinger 1993, Rubio 2007

- Rubio 2007 and references therein

- Zólyomi 1993; Also Woods, Cristopher, 2008: The Grammar of Perspective: The Sumerian Conjugation Prefixes as a System of Voice

- E.g. Zólyomi 1993

- Rubio 2007

- Zólyomi 2005

- Zólyomi (2000). "Structural interference from Akkadian in Old Babylonian Sumerian" (PDF). Acta Sumerologica. 22.

- Zólyomi 1993, Attinger 1993

- Attinger 1993, Khachikyan 2007: ("Towards the Aspect System in Sumerian". In: Babel und Bibel 3.)

- "Epsd2/Sux/šum[give]".

- Zólyomi 1993

- Johnson 2004:22

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- "Cone of Enmetena, king of Lagash". 2020.

Bibliography

- Attinger, Pascal (1993). Eléments de linguistique sumérienne: La construction de du11/e/di. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck&Ruprecht. ISBN 3-7278-0869-1.

- Delitzsch, Friedrich (1914). Grundzüge der sumerischen Grammatik. J. C. Hinrichs. OCLC 923551546.

- Dewart, Leslie (1989). Evolution and Consciousness: The Role of Speech in the Origin and Development of Human Nature. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-2690-7.

- Diakonoff, I. M. (1976). "Ancient Writing and Ancient Written Language: Pitfalls and Peculiarities in the Study of Sumerian" (PDF). Assyriological Studies. 20 (Sumerological Studies in Honor of Thorkild Jakobsen): 99–121.

- Edzard, Dietz Otto (2003). Sumerian Grammar. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-12608-2. (grammar treatment for the advanced student)

- Halloran, John (11 August 1999). "Sumerian Lexicon" (PDF). Sumerian Language Page. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- Halloran, John Alan (2006). Sumerian Lexicon: A Dictionary Guide to the Ancient Sumerian Language. Logogram Pub. ISBN 978-0978-64291-4.

- Hayes, John (1990; 2nd ed. 2000), A Manual of Sumerian: Grammar and Texts. UNDENA, Malibu CA. ISBN 0-89003-197-5. (primer for the beginning student)

- Hayes, John (1997), Sumerian. Languages of the World/Materials #68, LincomEuropa, Munich. ISBN 3-929075-39-3. (41 pp. précis of the grammar)

- Jagersma, B. (2009), A Descriptive Grammar of Sumerian, Universitet Leiden, The Netherlands.

- Jestin, J. (1951), Abrégé de Grammaire Sumérienne, Geuthner, Paris. ISBN 2-7053-1743-0. (118pp overview and sketch, in French)

- Langdon, Stephen Herbert (1911). A Sumerian Grammar and Chrestomathy, with a Vocabulary of the Principal Roots in Sumerian, and List of the Most Important Syllabic and Vowel Transcriptions, by Stephen Langdon ... P. Geuthner. OCLC 251014503.

- Michalowski, Piotr (1980). "Sumerian as an Ergative Language". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 32 (2): 86–103. doi:10.2307/1359671. JSTOR 1359671. S2CID 164022054.

- Michalowski,Piotr, (2004), "Sumerian", The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages pp 19–59, ed. Roger Woodward. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-05-2156-256-0.

- Pinches, Theophilus G., "Further Light upon the Sumerian Language.", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1914, pp. 436–40

- Prince, John D. (1908). Materials for a Sumerian lexicon with a grammatical introduction. Assyriologische Bibliothek, 19. Hinrichs. OCLC 474982763.

- Prince, J. Dynely (October 1914). "Delitzsch's Sumerian Grammar". American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. U of Chicago. 31 (1): 67–78. doi:10.1086/369755. ISSN 1062-0516. S2CID 170226826.

- Rubio, Gonzalo (2007), "Sumerian Morphology". In Morphologies of Asia and Africa, vol. 2, pp. 1327–1379. Edited by Alan S. Kaye. Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, IN, ISBN 1-57506-109-0.

- Thomsen, Marie-Louise (2001) [1984]. The Sumerian Language: An Introduction to Its History and Grammatical Structure. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag. ISBN 87-500-3654-8. (Well-organized with over 800 translated text excerpts.)

- Volk, Konrad (1997). A Sumerian Reader. Rome: Pontificio Istituto Biblico. ISBN 88-7653-610-8. (collection of Sumerian texts, some transcribed, none translated)

- Zólyomi, Gábor. 2017. An Introduction to the Grammar of Sumerian. Open Access textbook, Budapest.

Further reading

- Friedrich Delitzsch (1914). Sumerisches glossar. J. C. Hinrichs. p. 295. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- Ebeling, J., & Cunningham, G. (2007). Analysing literary Sumerian : corpus-based approaches. London: Equinox. ISBN 1-84553-229-5

- Halloran, J. A. (2007). Sumerian lexicon: a dictionary guide to the ancient Sumerian language. Los Angeles, Calif: Logogram. ISBN 0-9786429-1-0

- Shin Shifra, Jacob Klein (1996). In Those Far Days. Tel Aviv, Am Oved and The Israeli Center for Libraries' project for translating Exemplary Literature to Hebrew. This is an anthology of Sumerian and Akkadian poetry, translated into Hebrew.

External links

- General

- Akkadian Unicode Font (to see Cuneiform text) Archive

- Linguistic overviews

- A Descriptive Grammar of Sumerian by Abraham Hendrik Jagersma (preliminary version)

- Sumerisch (An overview of Sumerian by Ernst Kausen, in German)

- Chapter VI of Magie chez les Chaldéens et les origines accadiennes (1874) by François Lenormant: the state of the art in the dawn of Sumerology, by the author of the first ever grammar of "Akkadian"

- Dictionaries

- Corpora

- The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL). Includes translations.

- CDLI: Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative a large corpus of Sumerian texts in transliteration, largely from the Early Dynastic and Ur III periods, accessible with images.

- Research

- Online publications arising from the ETCSL project (PDF)

- Structural Interference from Akkadian in Old Babylonian Sumerian by Gábor Zólyomi (PDF)

- Other online publications by Gábor Zólyomi (PDF)

- The Life and Death of the Sumerian Language in Comparative Perspective by Piotr Michalowski

- Online publications by Cale Johnson (PDF)

- Eléments de linguistique sumérienne (by Pascal Attinger, 1993; in French), at the digital library RERO DOC: Parts 1–4, Part 5.

- The Origin of Ergativity in Sumerian, and the Inversion in Pronominal Agreement: A Historical Explanation Based on Neo-Aramaic parallels, by E. Coghill & G. Deutscher, 2002 at the Internet Archive

.jpg.webp)