Ziggurat

A ziggurat (/ˈzɪɡʊˌræt/; Cuneiform: 𒅆𒂍𒉪, Akkadian: ziqqurratum,[2] D-stem of zaqārum 'to protrude, to build high',[3] cognate with other Semitic languages like Hebrew zaqar (זָקַר) 'protrude'[4][5]) is a type of massive structure built in ancient Mesopotamia. It has the form of a terraced compound of successively receding storeys or levels. Notable ziggurats include the Great Ziggurat of Ur near Nasiriyah, the Ziggurat of Aqar Quf near Baghdad, the now destroyed Etemenanki in Babylon, Chogha Zanbil in Khūzestān and Sialk Plus, Sumer in general. The Sumerians believed that the Gods lived in the temple at the top of the Ziggurats, so only priests and other highly respected individuals could enter. Society offered them many things such as music, harvest, and creating devotional statues to live in the temple.

History

The word ziggurat comes from ziqqurratum (height, pinnacle), in ancient Assyrian. From zaqārum, to be high up. The Ziggurat of Ur is a Neo-Sumerian ziggurat built by King Ur-Nammu, who dedicated it in honor of Nanna/Sîn in approximately the 21st century BC during the Third Dynasty of Ur.[6]

Description

.jpg.webp)

Ziggurats were built by ancient Sumerians, Akkadians, Elamites, Eblaites and Babylonians for local religions. Each ziggurat was part of a temple complex that included other buildings. The precursors of the ziggurat were raised platforms that date from the Ubaid period[7] during the sixth millennium BC. The ziggurats began as platforms (usually oval, rectangular or square). The ziggurat was a mastaba-like structure with a flat top. The sun-baked bricks made up the core of the ziggurat with facings of fired bricks on the outside. Each step was slightly smaller than the step below it. The facings were often glazed in different colors and may have had astrological significance. Kings sometimes had their names engraved on these glazed bricks. The number of floors ranged from two to seven.

According to archaeologist Harriet Crawford,

It is usually assumed that the ziggurats supported a shrine, though the only evidence for this comes from Herodotus, and physical evidence is non-existent ... The likelihood of such a shrine ever being found is remote. Erosion has usually reduced the surviving ziggurats to a fraction of their original height, but textual evidence may yet provide more facts about the purpose of these shrines. In the present state of our knowledge it seems reasonable to adopt as a working hypothesis the suggestion that the ziggurats developed out of the earlier temples on platforms and that small shrines stood on the highest stages ...[8]

Access to the shrine would have been by a series of ramps on one side of the ziggurat or by a spiral ramp from base to summit. The Mesopotamian ziggurats were not places for public worship or ceremonies. They were believed to be dwelling places for the gods, and each city had its own patron god. Only priests were permitted on the ziggurat or in the rooms at its base, and it was their responsibility to care for the gods and attend to their needs. The priests were very powerful members of Sumerian and Assyro-Babylonian society.

One of the best-preserved ziggurats is Chogha Zanbil in western Iran.[9] The Sialk ziggurat, in Kashan, Iran, is one of the oldest known ziggurats, dating to the early 3rd millennium BCE.[10][11] Ziggurat designs ranged from simple bases upon which a temple sat, to marvels of mathematics and construction which spanned several terraced stories and were topped with a temple.

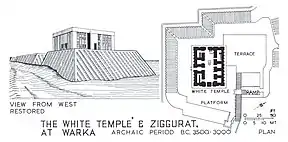

An example of a simple ziggurat is the White Temple of Uruk, in ancient Sumer. The ziggurat itself is the base on which the White Temple is set. Its purpose is to get the temple closer to the heavens, and provide access from the ground to it via steps. The Mesopotamians believed that these pyramid temples connected heaven and earth. In fact, the ziggurat at Babylon was known as Etemenanki, which means "House of the foundation of heaven and earth" in Sumerian.

The date of its original construction is unknown, with suggested dates ranging from the fourteenth to the ninth century BC, with textual evidence suggesting it existed in the second millennium.[12] Unfortunately, not much of even the base is left of this massive structure, yet archeological findings and historical accounts put this tower at seven multicolored tiers, topped with a temple of exquisite proportions. The temple is thought to have been painted and maintained an indigo color, matching the tops of the tiers. It is known that there were three staircases leading to the temple, two of which (side flanked) were thought to have only ascended half the ziggurat's height.

Interpretation and significance

According to Herodotus, at the top of each ziggurat was a shrine, although none of these shrines has survived.[7] One practical function of the ziggurats was a high place on which the priests could escape rising water that annually inundated lowlands and occasionally flooded for hundreds of kilometres, for example, the 1967 flood.[13] Another practical function of the ziggurat was security. Since the shrine was accessible only by way of three stairways,[14] a small number of guards could prevent non-priests from spying on the rituals at the shrine on top of the ziggurat, such as initiation rituals like the Eleusinian mysteries, cooking of sacrificial food and burning of sacrificial animals. Each ziggurat was part of a temple complex that included a courtyard, storage rooms, bathrooms, and living quarters, around which a city spread,[15] as well as a place for the people to worship.

Influence

The biblical account of the Tower of Babel has been associated by modern scholars to the massive construction undertakings of the ziggurats of Mesopotamia,[16] and in particular to the ziggurat of Etemenanki in Babylon in light of the Tower of Babel Stele[17] describing its restoration by Nebuchadnezzar II.

The design of Egyptian pyramids, especially the stepped designs of the oldest pyramids (Pyramid of Zoser at Saqqara, 2600 BCE), may have been an evolution from the ziggurats built in Mesopotamia.[18][19]

The shape of the ziggurat experienced a revival in modern architecture and Brutalist architecture starting in the 1970s. The Al Zaqura Building is a government building situated in Baghdad. It serves the office of the prime minister of Iraq. The Babylon Hotel in Baghdad also is inspired by the ziggurat. The Chet Holifield Federal Building is colloquially known as "the Ziggurat" due to its form. It is a United States government building in Laguna Niguel, California, built between 1968 and 1971. Further examples include The Ziggurat in West Sacramento, California, and the SIS Building in London.

See Category:Ziggurat style modern architecture

References

Citations

- Crüsemann, Nicola; Ess, Margarete van; Hilgert, Markus; Salje, Beate; Potts, Timothy (2019). Uruk: First City of the Ancient World. Getty Publications. p. 325. ISBN 978-1-60606-444-3.

- "Search Entry". www.assyrianlanguages.org. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- "Search Entry". www.assyrianlanguages.org. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- "מילון מורפיקס | זקר באנגלית | פירוש זקר בעברית". www.morfix.co.il. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- see also Akkadian zaqru 'protruding, high', corresponding to Hebrew zaqur (זָקוּר) 'protruding out, upwards'

- "The Ziggurat of Ur". British Museum. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Crawford 1993, p. 73.

- Crawford 1993, p. 85.

- "Tchogha Zanbil". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

It is the largest ziggurat outside of Mesopotamia and the best preserved of this type of stepped pyramidal monument.

- Matthews, R; Nashli, H. F., eds. (2013). The Neolithisation of Iran: the formation of new societies. Oxford: British Association for Near Eastern Archaeology and Oxbow Books. p. 272.

- Fazeli, H.; Beshkani A.; Markosian A.; Ilkani H.; Young R. L. (2010). "The Neolithic to Chalcolithic Transition in the Qazvin Plain, Iran: Chronology and Subsistence Strategies". Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran and Turan (41): 1–17.

- George, Andrew R. (2007). "The Tower of Babel: Archaeology, history, and cuneiform texts" (PDF). Archiv für Orientforschung. 2005/2006 (51): 75–95.

- Aramco World Magazine, March–April 1968, pp. 32–33

- Crawford 1993, p. 75.

- Oppenheimer 1977, pp. 112, 326–328.

- Harris, Stephen L. (2002). Understanding the Bible. McGraw-Hill. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780767429160.

- "MS 2063 - The Schoyen Collection". www.schoyencollection.com. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- "The stepped design of the Pyramid of Zoser at Saqqara, the oldest known pyramid along the Nile, suggests that it was borrowed from the Mesopotamian ziggurat concept." in Held, Colbert C. (University of Nebraska) (2018). Middle East Patterns, Student Economy Edition: Places, People, and Politics. Routledge. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-429-96199-1.

- Samuels, Charlie (2010). Ancient Science (Prehistory – A.D. 500): Prehistory-A.D. 500. Gareth Stevens Publishing LLLP. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4339-4137-5.

Sources

- Oppenheimer, A. Leo (1977). Ancient Mesopotamia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-63187-7.

- Tillison, Malachi (1993). Sumer and the Sumerians. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38850-3.

- Crawford, Harriet (1993). Sumer and the Sumerians. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38850-3.

Further reading

- Black, J.A.; Green, A. "Ziggurat". In Bienkowski, P.; Millard, A. (eds.). Dictionary of the Ancient Near East. London: British Museum. pp. 327–328.

- Beck, Roger B.; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S.; Naylor, Phillip C.; Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- Busink, T. (1970). "L´origine et évolution de la ziggurat babylonienne". Jaarbericht van Het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap Ex Oriente Lux. 21: 91–141.

- Chadwick, R. (November 1992). "Calendars, Ziggurats, and the Stars". The Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies Bulletin. Toronto. 24: 7–24.

- Killick, R.G. "Ziggurat". In Turner, J. (ed.). The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 33. New York & London: Macmillan. pp. 675–676.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2002). Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-026574-0.

- Lenzen, H.J. (1942). Die Entwicklung der Zikurrat von ihren Anfängen bis zur Zeit der III. Dynastie von Ur. Leipzig.

- Roaf, M. (1990). Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East. New York. pp. 104–107.

- Stone, E.C. (1997). "Ziggurat". In Meyers, E.M. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East. Vol. 5. New York & Oxford: Oxford. pp. 390–391.