Enlil

Enlil,[lower-alpha 1] later known as Elil, is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with wind, air, earth, and storms.[5] He is first attested as the chief deity of the Sumerian pantheon,[6] but he was later worshipped by the Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Hurrians. Enlil's primary center of worship was the Ekur temple in the city of Nippur, which was believed to have been built by Enlil himself and was regarded as the "mooring-rope" of heaven and earth. He is also sometimes referred to in Sumerian texts as Nunamnir. According to one Sumerian hymn, Enlil himself was so holy that not even the other gods could look upon him. Enlil rose to prominence during the twenty-fourth century BC with the rise of Nippur. His cult fell into decline after Nippur was sacked by the Elamites in 1230 BC and he was eventually supplanted as the chief god of the Mesopotamian pantheon by the Babylonian national god Marduk.

| Enlil | |

|---|---|

Statuette of Enlil sitting on his throne from the site of Nippur, dated to 1800 – 1600 BC, now on display in the Iraq Museum | |

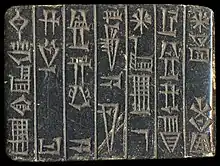

| Cuneiform | 𒀭𒂗𒆤 |

| Abode | Nippur |

| Symbol | Horned crown |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | An and Ki |

| Consort | Ninlil, Ninhursag,[1] Ki |

| Children | Ninurta, Nanna, Nergal, Ninazu, and Enbilulu |

| Equivalents | |

| Babylonian equivalent | Elil |

| Hurrian equivalent | Kumarbi |

| Hebrew equivalent | El |

| Canaanite equivalent | El or Dagan |

Enlil plays a vital role in the Sumerian creation myth; he separates An (heaven) from Ki (earth), thus making the world habitable for humans. In the Sumerian flood myth, Enlil rewards Ziusudra with immortality for having survived the flood and, in the Babylonian flood myth, Enlil is the cause of the flood himself, having sent the flood to exterminate the human race, who made too much noise and prevented him from sleeping. The myth of Enlil and Ninlil is about Enlil's serial seduction of the goddess Ninlil in various guises, resulting in the conception of the moon-god Nanna and the Underworld deities Nergal, Ninazu, and Enbilulu. Enlil was regarded as the inventor of the mattock and the patron of agriculture. Enlil also features prominently in several myths involving his son Ninurta, including Anzû and the Tablet of Destinies and Lugale.

Etymology

Enlil's name comes from ancient Sumerian EN (𒂗), meaning "lord" and LÍL (𒆤), the meaning of which is contentious,[7][2][8] and which has sometimes been interpreted as meaning winds as a weather phenomenon (making Enlil a weather and sky god, "Lord [of the] Wind" or "Lord [of the] Storm"),[9][3][4] or alternatively as signifying a spirit or phantom whose presence may be felt as stirring of the air, or possibly as representing a partial Semitic loanword rather than a Sumerian word at all.[10] Enlil's name is not a genitive construction,[11] suggesting that Enlil was seen as the personification of LÍL rather than merely the cause of LÍL.[11]

Piotr Steinkeller has written that the meaning of LÍL may not actually be a clue to a specific divine domain of Enlil's, whether storms, spirits, or otherwise, since Enlil may have been "a typical universal god [...] without any specific domain."[12]

Worship

Enlil who sits broadly on the white dais, on the lofty dais, who perfects the decrees of power, lordship, and princeship, the earth-gods bow down in fear before him, the heaven-gods humble themselves before him...

— Sumerian hymn to Enlil, translated by Samuel Noah Kramer[13]

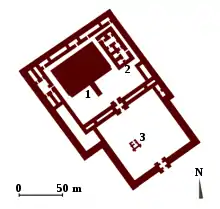

Enlil was the patron god of the Sumerian city-state of Nippur[14] and his main center of worship was the Ekur temple located there.[15] The name of the temple literally means "Mountain House" in ancient Sumerian.[16] The Ekur was believed to have been built and established by Enlil himself.[16] It was believed to be the "mooring-rope" of heaven and earth,[16] meaning that it was seen as "a channel of communication between earth and heaven".[17] A hymn written during the reign of Ur-Nammu, the founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur, describes the E-kur in great detail, stating that its gates were carved with scenes of Imdugud, a lesser deity sometimes shown as a giant bird, slaying a lion and an eagle snatching up a sinner.[16]

The Sumerians believed that the sole purpose of humanity's existence was to serve the gods.[18][19] They thought that a god's statue was a physical embodiment of the god himself.[20][21] As such, cult statues were given constant care and attention[22][20] and a set of priests were assigned to tend to them.[23] People worshipped Enlil by offering food and other human necessities to him.[18] The food, which was ritually laid out before the god's cult statue in the form of a feast,[22][20] was believed to be Enlil's daily meal,[18] but, after the ritual, it would be distributed among his priests.[18] These priests were also responsible for changing the cult statue's clothing.[21]

The Sumerians envisioned Enlil as a benevolent, fatherly deity, who watches over humanity and cares for their well-being.[24] One Sumerian hymn describes Enlil as so glorious that even the other gods could not look upon him.[25][26] The same hymn also states that, without Enlil, civilization could not exist.[26] Enlil's epithets include titles such as "the Great Mountain" and "King of the Foreign Lands".[25] Enlil is also sometimes described as a "raging storm", a "wild bull", and a "merchant".[25] The Mesopotamians envisioned him as a creator, a father, a king, and the supreme lord of the universe.[25][27] He was also known as "Nunamnir"[25] and is referred to in at least one text as the "East Wind and North Wind".[25]

Kings regarded Enlil as a model ruler and sought to emulate his example.[28] Enlil was said to be supremely just[13] and intolerant towards evil.[13] Rulers from all over Sumer would travel to Enlil's temple in Nippur to be legitimized.[29] They would return Enlil's favor by devoting lands and precious objects to his temple as offerings.[30] Nippur was the only Sumerian city-state that never built a palace;[18] this was intended to symbolize the city's importance as the center of the cult of Enlil by showing that Enlil himself was the city's king.[18] Even during the Babylonian Period, when Marduk had superseded Enlil as the supreme god, Babylonian kings still traveled to the holy city of Nippur to seek recognition of their right to rule.[30]

Enlil first rose to prominence during the twenty-fourth century BC, when the importance of the god An began to wane.[31][32] During this time period, Enlil and An are frequently invoked together in inscriptions.[31] Enlil remained the supreme god in Mesopotamia throughout the Amorite Period,[33] with Amorite monarchs proclaiming Enlil as the source of their legitimacy.[33] Enlil's importance began to wane after the Babylonian king Hammurabi conquered Sumer.[34] The Babylonians worshipped Enlil under the name "Elil"[5] and the Hurrians syncretized him with their own god Kumarbi.[5] In one Hurrian ritual, Enlil and Apantu are invoked as "the father and mother of Išḫara".[35] Enlil is also invoked alongside Ninlil as a member of "the mighty and firmly established gods".[35]

During the Kassite Period (c. 1592 BC – 1155 BC), Nippur briefly managed to regain influence in the region and Enlil rose to prominence once again.[34] From around 1300 BC onwards, Enlil was syncretized with the Assyrian national god Aššur,[36] who was the most important deity in the Assyrian pantheon.[37] Then, in 1230 BC, the Elamites attacked Nippur and the city fell into decline, taking the cult of Enlil along with it.[34] Approximately one hundred years later, Enlil's role as the head of the pantheon was given to Marduk, the national god of the Babylonians.[34]

Iconography

Enlil was represented by the symbol of a horned cap, which consisted of up to seven superimposed pairs of ox-horns.[38] Such crowns were an important symbol of divinity;[39][40] gods had been shown wearing them ever since the third millennium BC.[39] The horned cap remained consistent in form and meaning from the earliest days of Sumerian prehistory up until the time of the Persian conquest and beyond.[39][21]

The Sumerians had a complex numerological system, in which certain numbers were believed to hold special ritual significance.[41] Within this system, Enlil was associated with the number fifty, which was considered sacred to him.[42] Enlil was part of a triad of deities, which also included An and Enki.[43][44][45][46] These three deities together were the embodiment of all the fixed stars in the night sky.[47][45] An was identified with all the stars of the equatorial sky, Enlil with those of the northern sky, and Enki with those of the southern sky.[47][45] The path of Enlil's celestial orbit was a continuous, symmetrical circle around the north celestial pole,[48] but those of An and Enki were believed to intersect at various points.[49] Enlil was associated with the constellation Boötes.[25]

Mythology

Origins myths

The main source of information about the Sumerian creation myth is the prologue to the epic poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld (ETCSL 1.8.1.4),[50] which briefly describes the process of creation: originally, there was only Nammu, the primeval sea.[51] Then, Nammu gave birth to An, the sky, and Ki, the earth.[51] An and Ki mated with each other, causing Ki to give birth to Enlil.[51] Enlil separated An from Ki and carried off the earth as his domain, while An carried off the sky.[52] Enlil marries his mother, Ki, and from this union all the plant and animal life on earth is produced.[53]

Enlil and Ninlil (ETCSL 1.2.1) is a nearly complete 152-line Sumerian poem describing the affair between Enlil and the goddess Ninlil.[54][55] First, Ninlil's mother Nunbarshegunu instructs Ninlil to go bathe in the river.[56] Ninlil goes to the river, where Enlil seduces her and impregnates her with their son, the moon-god Nanna.[55] Because of this, Enlil is banished to Kur, the Sumerian underworld.[55] Ninlil follows Enlil to the underworld, where he impersonates the "man of the gate".[57] Ninlil demands to know where Enlil has gone, but Enlil, still impersonating the gatekeeper, refuses to answer.[57] He then seduces Ninlil and impregnates her with Nergal, the god of death.[58] The same scenario repeats, only this time Enlil instead impersonates the "man of the river of the nether world, the man-devouring river"; once again, he seduces Ninlil and impregnates her with the god Ninazu.[59] Finally, Enlil impersonates the "man of the boat"; once again, he seduces Ninlil and impregnates her with Enbilulu, the "inspector of the canals".[60]

The story of Enlil's courtship with Ninlil is primarily a genealogical myth invented to explain the origins of the moon-god Nanna, as well as the various gods of the Underworld,[54] but it is also, to some extent, a coming-of-age story describing Enlil and Ninlil's emergence from adolescence into adulthood.[61] The story also explains Ninlil's role as Enlil's consort; in the poem, Ninlil declares, "As Enlil is your master, so am I also your mistress!"[62] The story is also historically significant because, if the current interpretation of it is correct, it is the oldest known myth in which a god changes shape.[54]

Flood myth

In the Sumerian version of the flood story (ETCSL 1.7.4), the causes of the flood are unclear because the portion of the tablet recording the beginning of the story has been destroyed.[63] Somehow, a mortal known as Ziusudra manages to survive the flood, likely through the help of the god Enki.[64] The tablet begins in the middle of the description of the flood.[64] The flood lasts for seven days and seven nights before it subsides.[65] Then, Utu, the god of the Sun, emerges.[65] Ziusudra opens a window in the side of the boat and falls down prostrate before the god.[65] Next, he sacrifices an ox and a sheep in honor of Utu.[65] At this point, the text breaks off again.[65] When it picks back up, Enlil and An are in the midst of declaring Ziusudra immortal as an honor for having managed to survive the flood. The remaining portion of the tablet after this point is destroyed.[65]

In the later Akkadian version of the flood story, recorded in the Epic of Gilgamesh, Enlil actually causes the flood,[66] seeking to annihilate every living thing on earth because the humans, who are vastly overpopulated, make too much noise and prevent him from sleeping.[67] In this version of the story, the hero is Utnapishtim,[68] who is warned ahead of time by Ea, the Babylonian equivalent of Enki, that the flood is coming.[69] The flood lasts for seven days; when it ends, Ishtar, who had mourned the destruction of humanity,[70] promises Utnapishtim that Enlil will never cause a flood again.[71] When Enlil sees that Utnapishtim and his family have survived, he is outraged,[72] but his son Ninurta speaks up in favor of humanity, arguing that, instead of causing floods, Enlil should simply ensure that humans never become overpopulated by reducing their numbers using wild animals and famines.[73] Enlil goes into the boat; Utnapishtim and his wife bow before him.[73] Enlil, now appeased, grants Utnapishtim immortality as a reward for his loyalty to the gods.[74]

Chief god and arbitrator

Plucks at the roots, tears at the crown, the pickax spares the... plants; the pickax, its fate is decreed by father Enlil, the pickax is exalted.

— Enlil's Invention of the Pickax, translated by Samuel Noah Kramer[75]

A nearly complete 108-line poem from the Early Dynastic Period (c. 2900 – 2350 BC) describes Enlil's invention of the mattock,[76][77] a key agricultural pick, hoe, ax, or digging tool of the Sumerians.[78][77] In the poem, Enlil conjures the mattock into existence and decrees its fate.[79] The mattock is described as gloriously beautiful; it is made of pure gold and its head is carved from lapis lazuli.[79] Enlil gives the tool over to the humans, who use it to build cities,[75] subjugate their people,[75] and pull up weeds.[75] Enlil was believed to aid in the growth of plants.[78]

The Sumerian poem Enlil Chooses the Farmer-God (ETCSL 5.3.3) describes how Enlil, hoping "to establish abundance and prosperity", creates two gods Emesh and Enten, a shepherd and a farmer, respectively.[80] The two gods argue and Emesh lays claim to Enten's position.[81] They take the dispute before Enlil, who rules in favor of Enten;[82] the two gods rejoice and reconcile.[82]

Ninurta myths

In the Sumerian poem Lugale (ETCSL 1.6.2), Enlil gives advice to his son, the god Ninurta, advising him on a strategy to slay the demon Asag.[83] This advice is relayed to Ninurta by way of Sharur, his enchanted talking mace, which had been sent by Ninurta to the realm of the gods to seek counsel from Enlil directly.[83]

In the Old, Middle, and Late Babylonian myth of Anzû and the Tablet of Destinies, the Anzû, a giant, monstrous bird,[84] betrays Enlil and steals the Tablet of Destinies,[85] a sacred clay tablet belonging to Enlil that grants him his authority,[86] while Enlil is preparing for a bath.[87] The rivers dry up and the gods are stripped of their powers.[87] The gods send Adad, Gerra, and Shara to defeat the Anzû,[87] but all of them fail.[87] Finally, Ea proposes that the gods should send Ninurta, Enlil's son.[87] Ninurta successfully defeats the Anzû and returns the Tablet of Destinies to his father.[87] As a reward, Ninurta is a granted a prominent seat on the council of the gods.[87]

War of the gods

A badly damaged text from the Neo-Assyrian Period (911 — 612 BC) describes Marduk leading his army of Anunnaki into the sacred city of Nippur and causing a disturbance.[88] The disturbance causes a flood,[88] which forces the resident gods of Nippur under the leadership of Enlil to take shelter in the Eshumesha temple to Ninurta.[88] Enlil is enraged at Marduk's transgression and orders the gods of Eshumesha to take Marduk and the other Anunnaki as prisoners.[88] The Anunnaki are captured,[88] but Marduk appoints his front-runner Mushteshirhablim to lead a revolt against the gods of Eshumesha[89] and sends his messenger Neretagmil to alert Nabu, the god of literacy.[89] When the Eshumesha gods hear Nabu speak, they come out of their temple to search for him.[90] Marduk defeats the Eshumesha gods and takes 360 of them as prisoners of war, including Enlil himself.[90] Enlil protests that the Eshumesha gods are innocent,[90] so Marduk puts them on trial before the Anunnaki.[90] The text ends with a warning from Damkianna (another name for Ninhursag) to the gods and to humanity, pleading them not to repeat the war between the Anunnaki and the gods of Eshumesha.[90]

See also

- Ancient Mesopotamian religion

- El

- Hymn to Enlil

- Shu (Egyptian god)

- Yahweh

References

Citations

- Holland 2009.

- Halloran 2006.

- Holland 2009, p. 114.

- Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 182.

- Coleman & Davidson 2015, p. 108.

- Kramer 1983, pp. 115–121.

- Stone, Adam. "Enlil/Ellil (god)". Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses. Oracc and the UK Higher Education Academy. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Wang, Xianhua. The Metamorphosis of Enlil in Early Mesopotamia. pp. 6–22. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1989). "The líl of En-líl". In Berens, H.; Loding, D. M.; Roth, M. T. (eds.). DUMU-É-DUB-BA-A: Studies in Honor of Åke W. Sjöberg. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. pp. 267–276. ISBN 978-0934718981.

- Michalowski, Piotr (1998). "The unbearable lightness of Enlil". In Prosecký, J. (ed.). Intellectual Life of the Ancient Near East. The Oriental Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. p. 240.

- van der Toorn, Becking & Willem 1999, p. 356.

- Steinkeller, Piotr (1999). "On Rulers, Priests, and Sacred Marriage: Tracing the Evolution of Early Sumerian Kingship". In Watanabe, K. (ed.). Priests and Officials in the Ancient Near East. p. 114, n. 36.

- Kramer 1963, p. 120.

- Hallo 1996, pp. 231–234.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 74 and 76.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 74.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 53.

- Janzen 2004, p. 247.

- Kramer 1963, p. 123.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 94.

- Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 186.

- Nemet-Nejat 1998, pp. 186–187.

- Nemet-Nejat 1998, pp. 186–188.

- Kramer 1963, p. 119.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 76.

- Kramer 1963, p. 121.

- Kramer 1963, pp. 119–121.

- Grottanelli & Mander 2005, p. 5,162a.

- Littleton 2005, pp. 480–482.

- Littleton 2005, p. 482.

- Schneider 2011, p. 58.

- Kramer 1963, p. 118.

- Schneider 2011, pp. 58–59.

- Schneider 2011, p. 59.

- Archi 1990, p. 114.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 38.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 37.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 102.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 98.

- Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 185.

- McEvilley 2002, pp. 171–172.

- Röllig 1971, pp. 499–500.

- Tsumura 2005, p. 134.

- Delaporte 1996, p. 137.

- Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 203.

- Kramer 1963, pp. 118–122.

- Rogers 1998, p. 13.

- Levenda 2008, p. 29.

- Levenda 2008, pp. 29–30.

- Kramer 1961, pp. 30–33.

- Kramer 1961, pp. 37–40.

- Kramer 1961, pp. 37–41.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (2020-03-05). Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-83974-294-1.

- Kramer 1961, p. 43.

- Jacobsen 1946, pp. 128–152.

- Kramer 1961, p. 44.

- Kramer 1961, pp. 44–45.

- Kramer 1961, p. 45.

- Kramer 1961, p. 46.

- Black, Cunningham & Robson 2006, p. 106.

- Leick 2013, p. 66.

- Leick 2013, p. 67.

- Kramer 1961, p. 97.

- Kramer 1961, pp. 97–98.

- Kramer 1961, p. 98.

- Dalley 1989, p. 109.

- Dalley 1989, pp. 109–111.

- Dalley 1989, pp. 109–110.

- Dalley 1989, pp. 110–111.

- Dalley 1989, p. 113.

- Dalley 1989, pp. 114–115.

- Dalley 1989, p. 115.

- Dalley 1989, pp. 115–116.

- Dalley 1989, p. 116.

- Kramer 1961, p. 53.

- Kramer 1961, pp. 51–53.

- Green 2003, p. 37.

- Hooke 2004.

- Kramer 1961, p. 52.

- Kramer 1961, pp. 49–50.

- Kramer 1961, p. 50.

- Kramer 1961, p. 51.

- Penglase 1994, p. 68.

- Leick 1991, p. 9.

- Leick 1991, pp. 9–10.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 173.

- Leick 1991, p. 10.

- Oshima 2010, p. 145.

- Oshima 2010, pp. 145–146.

- Oshima 2010, p. 146.

Bibliography

- Archi, Alfonso (1990), "The Names of the Primeval Gods", Orientalia, NOVA, Rome, Italy: Gregorian Biblical Press, 59 (2): 114–129, JSTOR 43075881

- Black, Jeremy A.; Cunningham, Graham; Robson, Eleanor (2006), The Literature of Ancient Sumer, Oxford University Press, p. 106, ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, The British Museum Press, ISBN 0-7141-1705-6

- Coleman, J. A.; Davidson, George (2015), The Dictionary of Mythology: An A-Z of Themes, Legends, and Heroes, London, England: Arcturus Publishing Limited, p. 108, ISBN 978-1-78404-478-7

- Dalley, Stephanie (1989), Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-283589-0

- Delaporte, L. (1996) [1925], Mesopotamia: The Babylonian and Assyrian Civilization, The History of Civilization, translated by Childe, V. Gordon, New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-15588-6

- Green, Alberto R. W. (2003). The Storm-God in the Ancient Near East. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060699.

- Grottanelli, Cristiano; Mander, Pietro (2005), "Kingship: Kingship in the Ancient Mediterranean World", in Lindsay Jones (ed.), Encyclopedia of Religion (second ed.), Detroit, Michigan: MacMillan Reference USA, ISBN 978-0028657332

- Halloran, John A. (2006), Sumerian Lexicon: Version 3.0

- Hallo, William W. (1996), "Review: Enki and the Theology of Eridu", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 116, pp. 231–234

- Holland, Glenn Stanfield (2009), Gods in the Desert: Religions of the Ancient Near East, Lanham, Maryland, Boulder, Colorado, New York City, New York, Toronto, Ontario, and Plymouth, England: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., ISBN 978-0-7425-9979-6

- Hooke, S. H. (2004), Middle Eastern Mythology, Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0486435510

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1946), "Sumerian Mythology: A Review Article", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 5 (2): 128–152, doi:10.1086/370777, JSTOR 542374, S2CID 162344845

- Janzen, David (2004), The Social Meanings of Sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible: A Study of Four Writings, Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-018158-4

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961), Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.: Revised Edition, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-1047-6

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963), The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-45238-7

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983), "The Sumerian Deluge Myth: Reviewed and Revised", Anatolian Studies, British Institute at Ankara, 33: 115–121, doi:10.2307/3642699, JSTOR 3642699, S2CID 163489322

- Leick, Gwendolyn (1991), A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology, New York City, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-19811-9

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2013) [1994], Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature, New York City, New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-92074-7

- Levenda, Peter (2008), Stairway to Heaven: Chinese Alchemists, Jewish Kabbalists, and the Art of Spiritual Transformation, New York City, New York and London, England: Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc., ISBN 978-0-8264-2850-9

- Littleton, C. Scott (2005), Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology: Volume IV: Druids – Gilgamesh, Epic of, New York City, New York: Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 0-7614-7563-X

- McEvilley, Thomas (2002), The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, New York City, New York: Allworth Press, ISBN 1-58115-203-5

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998), Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, Daily Life, Greenwood, ISBN 978-0313294976

- Oshima, Takayoshi (2010), ""Damkianna Shall Not Bring Back Her Burden in the Future": A new Mythological Text of Marduk, Enlil and Damkianna", in Horowitz, Wayne; Gabbay, Uri; Vukosavokić, Filip (eds.), A Woman of Valor: Jerusalem Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Joan Goodnick Westenholz, vol. 8, Madrid, Spain: Biblioteca del Próximo Oriente Antiguo, ISBN 978-84-00-09133-0

- Rogers, John H. (1998), "Origins of the Ancient Astronomical Constellations: I: The Mesopotamian Traditions", Journal of the British Astronomical Association, London, England: The British Astronomical Association, 108 (1): 9–28, Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R

- Röllig, Werner (1971), "Götterzahlen", in E. Ebeling; B. Miessner, Eds. (eds.), Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischeen Archäologie, vol. 3, Berlin, Germany: Walther de Gruyter & Co., pp. 499–500

- Penglase, Charles (1994), Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-15706-4

- Schneider, Tammi J. (2011), An Introduction to Ancient Mesopotamian Religion, Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-8028-2959-7

- Tsumura, David Toshio (2005), Creation and Destruction: A Reappraisal of the Chaoskampf Theory in the Old Testament, Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, ISBN 1-57506-106-6

- van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Willem, Pieter (1999), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (second ed.), Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, ISBN 0-8028-2491-9

External links

- Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses: Enlil/Ellil (god)

- Gateway to Babylon: "Enlil and Ninlil", trans. Thorkild Jacobsen.

- Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature: "Enlil and Ninlil" (original Sumerian) and English translation

- Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature: Sumerian Flood myth (original Sumerian) and English translation

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg.webp)