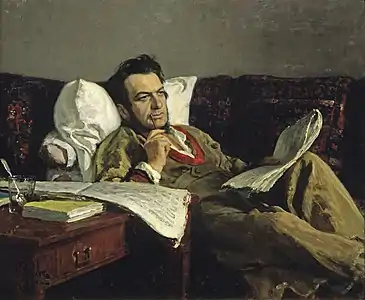

Mikhail Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (Russian: Михаил Иванович Глинка[lower-alpha 1], tr. Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka[lower-alpha 2], IPA: [mʲɪxɐˈil ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkə] (![]() listen); 1 June [O.S. 20 May] 1804 – 15 February [O.S. 3 February] 1857) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognition within his own country and is often regarded as the fountainhead of Russian classical music.[2] His compositions were an important influence on Russian composers, notably the members of The Five, who produced a distinctive Russian style of music.

listen); 1 June [O.S. 20 May] 1804 – 15 February [O.S. 3 February] 1857) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognition within his own country and is often regarded as the fountainhead of Russian classical music.[2] His compositions were an important influence on Russian composers, notably the members of The Five, who produced a distinctive Russian style of music.

Early life and education

Glinka was born in the village of Novospasskoye, not far from the Desna River in the Smolensk Governorate of the Russian Empire (now in the Yelninsky District of the Smolensk Oblast). His wealthy father had retired as an army captain, and the family had a strong tradition of loyalty and service to the tsars, and several members of his extended family had lively cultural interests. His great-great-grandfather was a Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth nobleman, Wiktoryn Władysław Glinka of the Trzaska coat of arms who was given lands in the Smolensk Voivodeship. In 1655, Wiktoryn converted to Eastern Orthodoxy with the new name Yakov Yakovlevich (Jacob, son of Jacob), and remained the owner of his lands under the tsar. The coat of arms was originally received after the conversion from Lithuanian Paganism to Catholicism according to the Union of Horodło.[3][4]

Mikhail was raised by his overprotective and pampering paternal grandmother, who fed him sweets, wrapped him in furs, and confined him to her room, which was kept at 25 °C (77 °F) Accordingly, he developed a sickly disposition, later in his life retaining the services of numerous physicians, and often falling victim to quacks. The only music he heard in his youthful confinement was the sounds of the village church bells and the folk songs of passing peasant choirs. The church bells were tuned to a dissonant chord, and so his ears became used to strident harmony. While his nurse would sometimes sing folksongs, the peasant choirs who sang using the podgolosochnaya technique (an improvised style—literally "under the voice"—using improvised dissonant harmonies below the melody) influenced his independence from the smooth progressions of Western harmony.

After his grandmother's death, he moved to his maternal uncle's estate some 10 kilometres (6 mi) away, where he heard his uncle's orchestra, whose repertoire included Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. At the age of about ten he heard them play a clarinet quartet by Finnish composer Bernhard Henrik Crusell, which had a profound effect upon him. "Music is my soul", he wrote many years later, recalling the experience. While his governess taught him Russian, German, French and geography, he also received instruction on the piano and violin.

At 13, Glinka went to the capital, Saint Petersburg, to attend a school for children of the nobility. He learned Latin, English, and Persian, studied mathematics and zoology, and considerably widened his musical experience. He had three piano lessons from John Field, the Irish composer of nocturnes, who spent some time in Saint Petersburg. He then continued his piano lessons with Charles Mayer and began composing.[3]

When he left school his father wanted him to join the Foreign Office, and he was appointed assistant secretary of the Department of Public Highways. The light work allowed Glinka to settle into the life of a musical dilettante, frequenting the city's drawing rooms and social gatherings. He was already composing a large amount of music, such as melancholy romances which amused the rich amateurs. His songs are among the most interesting parts of his work from this period.

In 1830, at a physician's recommendation, Glinka traveled to Italy with tenor Nikolai Kuzmich Ivanov. They took a leisurely pace, ambling through Germany and Switzerland, before settling in Milan. There, Glinka took lessons at the conservatory with Francesco Basili. He struggled with counterpoint, which he found irksome. After three years listening to singers, romancing women with his music, and meeting famous people including Mendelssohn and Berlioz, he became disenchanted with Italy. He realized that his life's mission was to return to Russia, write in a Russian manner, and do for Russian music what Donizetti and Bellini had done for Italian music.

His return took him through the Alps, and he stopped for a while in Vienna, where he heard the music of Franz Liszt. He stayed another five months in Berlin, where he studied composition under the distinguished teacher Siegfried Dehn. A Capriccio on Russian Themes for piano duet and an unfinished Symphony on Two Russian Themes were important products of this period.

When word reached Glinka of his father's death in 1834, he left Berlin and returned to Novospasskoye.

Career

While in Berlin, Glinka became enamored of a beautiful and talented singer, for whom he composed Six Studies for Contralto. He contrived a plan to return to her, but when his sister's German maid turned up without the necessary paperwork to cross to the border with him, he abandoned his plan as well as his love and turned north for Saint Petersburg. There he reunited with his mother, and made the acquaintance of Maria Petrovna Ivanova. After a brief courtship, they married, but the marriage was short-lived, as Maria was tactless and uninterested in his music. His initial fondness for her was said to have inspired the trio in the first act of his opera A Life for the Tsar (1836), but his naturally sweet disposition coarsened under his wife's and mother-in-law's constant criticism. When the marriage ended, she remarried, and Glinka moved in with his mother, and later with his sister, Lyudmila Shestakova.[3]

A Life for the Tsar was the first of Glinka's two great operas. It was originally entitled Ivan Susanin. Set in 1612, it tells the story of the Russian peasant and patriotic hero Ivan Susanin who sacrifices his life for the Tsar by leading astray a group of marauding Poles who were hunting him. The Tsar himself followed the work's progress with interest and suggested the change in the title. It was a great success at its premiere on 9 December 1836, under the direction of Catterino Cavos, who had written an opera on the same subject in Italy. The Tsar rewarded Glinka for his work with a ring valued at 4,000 rubles. (During the Soviet era, the opera was staged under its original title, Ivan Susanin.)

In 1837, Glinka was installed as the instructor of the Imperial Chapel Choir, with a yearly salary of 25,000 rubles and lodging at the court. In 1838, at the Tsar's suggestion, he traveled to Ukraine to gather new voices for the choir; the 19 new boys he found earned him another 1,500 rubles from the Tsar.

He soon embarked on his second opera, Ruslan and Lyudmila. The plot, based on the tale by Alexander Pushkin, was concocted in 15 minutes by Konstantin Bakhturin, a poet who was drunk at the time. Consequently, the opera is a dramatic muddle, yet the quality of Glinka's music is higher than in A Life for the Tsar. The override features a descending whole tone scale associated with the villainous dwarf Chernomor, who has abducted Lyudmila, daughter of the Prince of Kiev. There is much Italianate coloratura, and Act 3 contains several routine ballet numbers, but Glinka's great achievement lies in his use of folk melody which becomes thoroughly infused into the musical argument. Much of the borrowed folk material is oriental in origin. When it debuted on 9 December 1842, it was received coolly, but subsequently gained popularity.

Later years

.png.webp)

Glinka went through a dejected year after the poor reception of Ruslan and Lyudmila. His spirits rose when he travelled to Paris and Spain. In Spain he met Don Pedro Fernández, his secretary and companion for the last nine years of his life.[5] In Paris, Hector Berlioz conducted some excerpts from Glinka's operas and wrote an appreciative article about him. Glinka in turn admired Berlioz's music and resolved to compose some fantasies pittoresques for orchestra. Beginning in 1852, he spent two years in Paris, living quietly and frequently visiting the botanical and zoological gardens. He then moved to Berlin where, after five months, he died suddenly on 15 February 1857, following a cold. He was buried in Berlin, but a few months later his body was taken to Saint Petersburg and reinterred in the cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery.

The genesis of a Russian style

Glinka was the beginning of a new direction in Russian music.[6][7] Musical culture arrived in Russia from Europe, and for the first time specifically Russian music began to appear, in Glinka's operas. Historical events were often used as its basis, but for the first time they were presented realistically.[7][8]

The first to note this new direction was Alexander Serov.[9] He was then joined by his friend Vladimir Stasov,[9] who became the theorist of this cultural trend;[8] it was developed further by composers of "The Five".[6][7]

Modern Russian music critic Viktor Korshikov wrote: "Russian musical culture [would not have developed] without...three operas—Ivan Soussanine, Ruslan and Ludmila, and the Stone Guest have created Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin. Soussanine is an opera where the main character is the people; Ruslan is the mythical, deeply Russian intrigue; and in Guest, the drama dominates over the softness of the beauty of sound."[10] Two of these operas—Ivan Soussanine and Ruslan and Ludmila—were Glinka's.

Glinka's work, and that of the composers and other creative people he inspired, has been instrumental in the development of a distinctly Russian artistic style that occupies a prominent place in world culture.

Legacy

After Glinka's death, the relative merits of his two operas became a topic of heated debate in the musical press, especially between Vladimir Stasov and his former friend Alexander Serov. Glinka's orchestral composition Kamarinskaya (1848) was said by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky to be "the acorn from which the oak" of later Russian symphonic music grew.[11]

In 1884, Mitrofan Belyayev founded the annual Glinka Prize, whose early winners included Alexander Borodin, Mily Balakirev, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Cesar Cui and Anatoly Lyadov.

Outside Russia, several of Glinka's orchestral works have been fairly popular in concerts and recordings. Besides the well-known overtures to the operas (especially the brilliantly energetic overture to Ruslan), his major orchestral works include the symphonic poem Kamarinskaya (1848), based on Russian folk songs; and two Spanish works, A Night in Madrid (1848, 1851) and Jota Aragonesa (1845). He also composed many art songs and piano pieces, and some chamber music.[12]

A lesser work that received attention in the last decade of the 20th century was Glinka's "Patrioticheskaya Pesnya", supposedly written for a contest for a national anthem in 1833. In 1990, the Supreme Soviet of Russia adopted it as the regional anthem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, which till then was the only Soviet constituent state without its own anthem.[13] Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Russian SFSR, the hymn was retained unofficially until it was officially confirmed as the Russian national anthem in 1993, where it remained as such until 2000.[14]

Three Russian conservatories are named after Glinka:

- Nizhny Novgorod State Conservatory (Russian: Нижегородская государственная консерватория им. М.И.Глинки)[15]

- Novosibirsk State Conservatory (Russian: Новосибирская государственная консерватория (академия) им. М.И.Глинки)[16]

- Magnitogorsk State Conservatory (Russian: Магнитогорская государственная консерватория)[17]

Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Chernykh named a minor planet 2205 Glinka in his honor. It was discovered in 1973.[18] A crater on Mercury is also named after him.

Glinkastraße in Berlin was named in Glinka's honor. In the wake of the George Floyd protests, the Berlin U-Bahn station Mohrenstraße was proposed to be renamed "Glinkastraße", which is adjacent to the station. The plan was cancelled due to Glinka's reputed antisemitism.[19]

In September 2022 a street that was named after Glinka in Dnipro was renamed to honor Queen Elizabeth II.[20]

In popular culture

The stirring overture to Glinka's opera Ruslan and Lyudmila is heard as the theme of the long-running U.S. television comedy series Mom. Its creators felt the fast-paced, complex orchestral music reflected the characters' struggles to overcome their destructive habits and keep up with the demands of daily life.[21]

Works

- See: List of compositions by Mikhail Glinka.

Media

References

Notes

- "Russian – ALA-LC transliteration system". transliteration.com. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- "...regarded by his compatriots as the source and fountainhead of Russian Music", in "Russian Symphony Orchestra", New York Times, 1904-11-13, p. 10.

- "Михаил Иванович Глинка — русский композитор". Школьное дополнительное образование: классическая музыка. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- "Glinka family COA". gerbovnik.ru (in Russian). General Armorial of the Noble Families of the Russian Empire. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Grove Music Online "Glinka"

- Mikhail Glinka

- Creativity M.I. Glinka // ru: Творчество М.И. Глинки (лекция)

- Culture: The Works of Glinka // ru: Творчество Глинки

- "Александр Серов (Alexander Serov)" (in Russian). Классическая музыка. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- Victor Korshikov. Do you want, I'll teach you to love the opera. About the music, and not only. The publishing house. Moscow, 2007 // ru: Виктор Коршиков. Хотите, я научу вас любить оперу. О музыке и не только. Издательство ЯТЬ. Москва, 2007

- "Mikhail Glinka — Repertory Archive". abt.org. American Ballet Theatre. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- Ю. Н. Фост — Память о М. И. Глинке в Берлине

- Decree of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR of 23.11.1990 on the national anthem of the RSFSR [On the National Anthem of the Russian SFSR]. Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR (in Russian). lawrussia.ru. 23 November 1990. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Presidential Decree" [Presidential Decree on the National Anthem of the Russian Federation]. President of the Russian Federation (in Russian). lawrussia.ru. 11 December 1993. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "Нижегородская государственная консерватория им. М.И.Глинки (НГК им. М.И.Глинки)" (in Russian). uic.nnov.ru. Archived from the original on 11 January 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- "conservatoire.ru". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- magkmusic.com

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 179. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

- "Mohrenstrasse: Berlin farce over renaming of 'racist' station". BBC News. 9 July 2020.

- "In the center of Dnipro, the street of Stepan Bandera appeared - the mayor". Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 21 September 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- "Through a Farce Darkly: How a Glinka Overture Became the Theme Song for the Sitcom "Mom"". WMFT, Chicago. 27 October 2017.

Sources

- Brown, David (1974). Mikhail Glinka, a biographical and critical study, Oxford University Press.

- Glinka Mikhail Ivanovich, biographic encyclopedia, in Russian on biografija.ru

- Knowles, John Paine (Ed.), Theodore Thomas, and Karl Klauser (1891). Famous Composers and Their Works, J.B. Millet Company.

- Taruskin, Richard, "Glinka, Mikhail" in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, (Ed.) Stanley Sadie (London, 1992) ISBN 0-333-73432-7

External links

Works by or about Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka at Wikisource

Works by or about Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka at Wikisource- List of works (in German)

- Cylinder recording of a Glinka composition, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- Glinka – the author of Russian national anthem (in Russian) by K.Kovalev

- Leicestershire Schools Symphony Orchestra performs Russlan and Ludmilla overture on YouTube A short video from 1998

- The chorus "Glory" from the opera "A Life for the Tsar" on YouTube

- Free scores by Mikhail Glinka at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Mikhail Glinka in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Turgenev and Glinka (with music samples)