Monopolistic competition

Monopolistic competition is a type of imperfect competition such that there are many producers competing against each other, but selling products that are differentiated from one another (e.g. by branding or quality) and hence are not perfect substitutes. In monopolistic competition, a company takes the prices charged by its rivals as given and ignores the impact of its own prices on the prices of other companies.[1][2] If this happens in the presence of a coercive government, monopolistic competition will fall into government-granted monopoly. Unlike perfect competition, the company maintains spare capacity. Models of monopolistic competition are often used to model industries. Textbook examples of industries with market structures similar to monopolistic competition include restaurants, cereals, clothing, shoes, and service industries in large cities. The "founding father" of the theory of monopolistic competition is Edward Hastings Chamberlin, who wrote a pioneering book on the subject, Theory of Monopolistic Competition (1933).[3] Joan Robinson published a book The Economics of Imperfect Competition with a comparable theme of distinguishing perfect from imperfect competition. Further work on monopolistic competition was undertaken by Dixit and Stiglitz who created the Dixit-Stiglitz model which has proved applicable used in the sub fields of international trade theory, macroeconomics and economic geography.

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

Monopolistically competitive markets have the following characteristics:

- There are many producers and many consumers in the market, and no business has total control over the market price.

- Consumers perceive that there are non-price differences among the competitors' products.

- Companies operate with the knowledge that their actions will not affect other companies' actions.

- There are few barriers to entry and exit.[4]

- Producers have a degree of control over price.

- The principal goal of the company is to maximise its profits.

- Factor prices and technology are given.

- A company is assumed to behave as if it knew its demand and cost curves with certainty.

- The decision regarding price and output of any company does not affect the behaviour of other companies in a group, i.e., impact of the decision made by a single company is spread sufficiently evenly across the entire group. Thus, there is no conscious rivalry among the company.

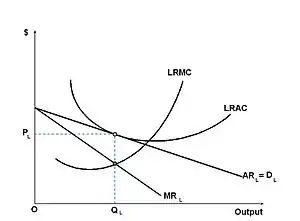

- Each company earns only normal profit in the long run.

- Each company spends substantial amount on advertisement. The publicity and advertisement costs are known as selling costs.

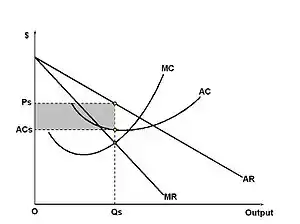

The long-run characteristics of a monopolistically competitive market are almost the same as a perfectly competitive market. Two differences between the two are that monopolistic competition produces heterogeneous products and that monopolistic competition involves a great deal of non-price competition, which is based on subtle product differentiation. A firm making profits in the short run will nonetheless only break even in the long run because demand will decrease and average total cost will increase. This means in the long run, a monopolistically-competitive company will make zero economic profit. This illustrates the amount of influence the company has over the market; because of brand loyalty, it can raise its prices without losing all of its customers. This means that an individual company's demand curve is downward sloping, in contrast to perfect competition, which has a perfectly elastic demand schedule.

Characteristics

There are six characteristics of monopolistic competition (MC):

- Product differentiation

- Many companies

- Freedom of entry and exit

- Independent decision making

- Some degree of market power

- Buyers and sellers do not have perfect information[5][6]

Product differentiation

MC companies sell products that have real or perceived non-price differences. Examples of these differences could include physical aspects of the product, location from which it sells the product or intangible aspects of the product, among others.[7] However, the differences are not so great as to eliminate other goods as substitutes. Technically, the cross price elasticity of demand between goods in such a market is positive. In fact, the cross elasticity of demand would be high.[8] MC goods are best described as close but imperfect substitutes.[8] The goods perform the same basic functions but have differences in qualities such as type, style, quality, reputation, appearance, and location that tend to distinguish them from each other. For example, the basic function of motor vehicles is the same—to move people and objects from point to point in reasonable comfort and safety. Yet there are many different types of motor vehicles such as motor scooters, motor cycles, trucks and cars, and many variations even within these categories.

Many companies

There are many companies in each MC product group and many companies on the side lines prepared to enter the market. A product group is a "collection of similar products".[9] The fact that there are "many companies" means that each company has a small market share.[10] This gives each MC company the freedom to set prices without engaging in strategic decision making regarding the prices of other companies (no mutual independence) and each company's actions have a negligible impact on the market. For example, a company could cut prices and increase sales without fear that its actions will prompt retaliatory responses from competitors.

The number of companies that an MC market structure will support at market equilibrium depends on factors such as fixed costs, economies of scale, and the degree of product differentiation. For example, the higher the fixed costs, the fewer companies the market will support.[11]

Freedom of entry and exit

Like perfect competition, under monopolistic competition also, the companies can enter or exit freely. The companies will enter when the existing companies are making super-normal profits. With the entry of new companies, the supply would increase which would reduce the price and hence the existing companies will be left only with normal profits. Similarly, if the existing companies are sustaining losses, some of the marginal firms will exit. It will reduce the supply due to which price would rise and the existing firms will be left only with normal profit.

Independent decision making

Each MC company independently sets the terms of exchange for its product.[12] The company gives no consideration to what effect its decision may have on its competitors.[12] The theory is that any action will have such a negligible effect on the overall market demand that an MC company can act without fear of prompting heightened competition. In other words, each company feels free to set prices as if it were a monopoly rather than an oligopoly.

Market power

MC companies have some degree of market power, although relatively low. Market power means that the company has control over the terms and conditions of exchange. All MC companies are price makers. An MC companies can raise its prices without losing all its customers. The company can also lower prices without triggering a potentially ruinous price war with competitors. The source of an MC company's market power is not barriers to entry since they are low. Rather, an MC company has market power because it has relatively few competitors, those competitors do not engage in strategic decision making and the companies sells differentiated product.[13] Market power also means that an MC company faces a downward sloping demand curve. In the long run, the demand curve is highly elastic, meaning that it is sensitive to price changes although it is not completely "flat". In the short run, economic profit is positive, but it approaches zero in the long run.[14]

Imperfect information

No other sellers or buyers have complete market information, like market demand or market supply.[15]

| Market Structure | Number of firms | Market power | Elasticity of demand | Product differentiation | Excess profits | Efficiency | Profit maximization condition | Pricing power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect competition | Infinite | None | Perfectly elastic | None | Yes/no (short/long) | Yes[16] | P=MR=MC[17] | Price taker[17] |

| Monopolistic competition | Many | Low | Highly elastic (long run)[18] | High[19] | Yes/No (Short/Long)[20] | No[21] | MR=MC[17] | Price setter[17] |

| Monopoly | One | High | Relatively inelastic | Absolute (across industries) | Yes | No | MR=MC[17] | Price setter[17] |

Inefficiency

There are two sources of inefficiency in the MC market structure. The first source of inefficiency is that, at its optimum output, the company charges a price that exceeds marginal costs. The MC company maximises profits where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Since the MC company's demand curve is downwards-sloping, the company will charge a price that exceeds marginal costs. The monopoly power possessed by a MC company means that at its profit-maximising level of production, there will be a net loss of consumer (and producer) surplus. The second source of inefficiency is the fact that MC companies operate with excess capacity. That is that the MC company's profit-maximising output is less than the output associated with minimum average cost. Both an MC and PC company will operate at a point where demand or price equals average cost. For a PC company, this equilibrium condition occurs where the perfectly elastic demand curve equals minimum average cost. A MC company's demand curve is not flat but is downwards-sloping. Thus, the demand curve will be tangential to the long-run average cost curve at a point to the left of its minimum. The result is excess capacity.[22]

Socially-undesirable aspects compared to perfect competition

- Selling costs: Producers under monopolistic competition often spend substantial amounts on advertising and publicity. Much of this expenditure is wasteful from the social point of view. The producer can reduce the price of the product instead of spending on publicity.

- Excess capacity: Under Imperfect competition, the installed capacity of every firm is large, but not fully used. Total output is, therefore, less than the output which is socially desirable. Since production capacity is not fully used, the resources lie idle. Therefore, the production under monopolistic competition is below the full capacity level.

- Unemployment: Idle capacity under monopolistic competition expenditure leads to unemployment. In particular, unemployment of workers leads to poverty and misery in the society. If idle capacity is fully used, the problem of unemployment can be solved to some extent.

- Cross transport: Under monopolistic competition expenditure is incurred on cross transportation. If the goods are sold locally, wasteful expenditure on cross transport could be avoided.

- Lack of specialisation: Under monopolistic competition, there is little scope for specialisation or standardisation. Product differentiation practised under this competition leads to wasteful expenditure. It is argued that instead of producing too many similar products, only a few standardised products may be produced. This would ensure better allocation of resources and would promote the economic success of the society.

- Inefficiency: Under perfect competition, an inefficient company is thrown out of the industry. But under monopolistic competition, inefficient companies continue to survive.

Problems

Monopolistically-competitive companies are inefficient, it is usually the case that the costs of regulating prices for products sold in monopolistic competition exceed the benefits of such regulation.[23] A monopolistically-competitive company might be said to be marginally inefficient because the company produces at an output where average total cost is not a minimum. A monopolistically-competitive market is productively inefficient market structure because marginal cost is less than price in the long run. Monopolistically-competitive markets are also allocative-inefficient, as the company charges prices that exceed marginal cost. Product differentiation increases total utility by better meeting people's wants than homogenous products in a perfectly competitive market.[23]

Another concern is that monopolistic competition fosters advertising. There are two main ways to conceive how advertising works under a monopolistic competition framework. Advertising can either cause a company's perceived demand curve to become more inelastic; or advertising causes demand for the company's product to increase. In either case, a successful advertising campaign may allow a company to sell a greater quantity or to charge a higher price, or both, and thus increase its profits.[24] This allows the creation of brand names. Advertising induces customers into spending more on products because of the name associated with them rather than because of rational factors. Defenders of advertising dispute this, arguing that brand names can represent a guarantee of quality and that advertising helps reduce the cost to consumers of weighing the trade-offs of numerous competing brands. There are unique information and information processing costs associated with selecting a brand in a monopolistically competitive environment. In a monopoly market, the consumer is faced with a single brand, making information gathering relatively inexpensive. In a perfectly competitive industry, the consumer is faced with many brands, but because the brands are virtually identical information gathering is also relatively inexpensive. In a monopolistically competitive market, the consumer must collect and process information on a large number of different brands to be able to select the best of them. In many cases, the cost of gathering information necessary to selecting the best brand can exceed the benefit of consuming the best brand instead of a randomly selected brand. The result is that the consumer is confused. Some brands gain prestige value and can extract an additional price for that.

Evidence suggests that consumers use information obtained from advertising not only to assess the single brand advertised, but also to infer the possible existence of brands that the consumer has, heretofore, not observed, as well as to infer consumer satisfaction with brands similar to the advertised brand.[25]

Examples

In many markets, such as toothpaste, soap, air conditioning, smartphones and toilet paper, producers practice product differentiation by altering the physical composition of products, using special packaging, or simply claiming to have superior products based on brand images or advertising.[26]

See also

- Atomistic market

- Business oligarch

- Government-granted monopoly

- Imperfect competition

- Microeconomics

- Monopolistic competition in international trade

- Monopoly

- Natural monopoly

- Oligopoly

- Perfect competition

Notes

- Krugman, Paul; Obstfeld, Maurice (2008). International Economics: Theory and Policy. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-55398-0.

- Poiesz, Theo B. C. (2004). "The Free Market Illusion Psychological Limitations of Consumer Choice" (PDF). Tijdschrift voor Economie en Management. 49 (2): 309–338.

- "Monopolistic Competition". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Gans, Joshua; King, Stephen; Stonecash, Robin; Mankiw, N. Gregory (2003). Principles of Economics. Thomson Learning. ISBN 0-17-011441-4.

- Goodwin, N.; Nelson, J.; Ackerman, F.; Weisskopf, T. (2009). Microeconomics in Context (2nd ed.). Sharpe. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-7656-2301-0.

- Hirschey, M. (2000). Managerial Economics (Rev. ed.). Fort Worth: Dryden. p. 443. ISBN 0-03-025649-6.

- Klingensmith, J. Zachary (26 August 2019), "Monopolistic Competition", Introduction to Microeconomics, Affordable Course Transformation: The Pennsylvania State University, retrieved 1 November 2020

- Krugman; Wells (2009). Microeconomics (2nd ed.). New York: Worth. ISBN 978-0-7167-7159-3.

- Samuelson, W.; Marks, S. (2003). Managerial Economics (4th ed.). Wiley. p. 379. ISBN 0-470-00044-9.

- "Imperfect Competition: Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly". www2.harpercollege.edu. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Perloff, J. (2008). Microeconomics Theory & Applications with Calculus. Boston: Pearson. p. 485. ISBN 978-0-321-27794-7.

- Colander, David C. (2008). Microeconomics (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-07-334365-5.

- Perloff, J. (2008). Microeconomics Theory & Applications with Calculus. Boston: Pearson. p. 483. ISBN 978-0-321-27794-7.

- Staff, Investopedia. "Monopolistic Competition Definition". Investopedia. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Goodwin, N.; Nelson, J.; Ackerman, F.; Weisskopf, T. (2009). Microeconomics in Context (2nd ed.). Sharpe. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-7656-2301-0.

- Ayers, R.; Collinge, R. (2003). Microeconomics: Explore & Apply. Pearson. pp. 224–225. ISBN 0-13-177714-9.

- Perloff, J. (2008). Microeconomics Theory & Applications with Calculus. Boston: Pearson. p. 445. ISBN 978-0-321-27794-7.

- Ayers, R.; Collinge, R. (2003). Microeconomics: Explore & Apply. Pearson. p. 280. ISBN 0-13-177714-9.

- Pindyck, R.; Rubinfeld, D. (2001). Microeconomics (5th ed.). London: Prentice-Hall. p. 424. ISBN 0-13-030472-7.

- Pindyck, R.; Rubinfeld, D. (2001). Microeconomics (5th ed.). London: Prentice-Hall. p. 425. ISBN 0-13-030472-7.

- Pindyck, R.; Rubinfeld, D. (2001). Microeconomics (5th ed.). London: Prentice-Hall. p. 427. ISBN 0-13-030472-7.

- The company has not reached full capacity or minimum efficient scale. Minimum efficient scale is the level of production at which the long-run average cost curve first reaches its minimum. It is the point where the LRATC curve "begins to bottom out." Perloff, J. (2008). Microeconomics Theory & Applications with Calculus. Boston: Pearson. pp. 483–484. ISBN 978-0-321-27794-7.

- "What's so bad about monopoly power?". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- "Reading: Advertising and Monopolistic Competition | Microeconomics". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Antony Davies & Thomas Cline (2005). "A Consumer Behavior Approach to Modeling Monopolistic Competition". Journal of Economic Psychology. 26 (6): 797–826. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2005.05.003.

- Bain, Joe S. (1 September 2021). "Monopoly and Competition". Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 October 2022.