Moorgate tube crash

The Moorgate tube crash occurred on 28 February 1975 at 8:46 am on the London Underground's Northern City Line; 43 people died and 74 were injured after a train failed to stop at the line's southern terminus, Moorgate station, and crashed into its end wall. It is considered the worst peacetime accident on the London Underground. No fault was found with the train, and the inquiry by the Department of the Environment concluded that the accident was caused by the actions of Leslie Newson, the 56-year-old driver.

| Moorgate tube crash | |

|---|---|

Dead-end tunnel at platform 9, Moorgate station | |

| Details | |

| Date | 28 February 1975 8:46 am |

| Location | Moorgate, London |

| Line | Northern City Line |

| Operator | London Underground |

| Cause | Driver failed to stop |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 1 |

| Passengers | c. 300 |

| Deaths | 43 |

| Injured | 74 |

| List of UK rail accidents by year | |

The crash forced the first carriage into the roof of the tunnel at the front and back, but the middle remained on the trackbed; the 16-metre-long (52 ft) coach was crushed to 6.1 metres (20 ft). The second carriage was concertinaed at the front as it collided with the first, and the third rode over the rear of the second. The brakes were not applied and the dead man's handle was still depressed when the train crashed. The London Fire Brigade, Ambulance Service and City of London Police attended the scene. It took 13 hours to remove the injured, many of whom had to be cut free from the wreckage. With no services running into the adjoining platform to produce the piston effect pushing air into the station, ventilation was poor and temperatures in the tunnel rose to over 49 °C (120 °F). It took a further four days to extract the last body, that of Newson; his cab, normally 91 centimetres (3 ft) deep, had been crushed to 15 centimetres (6 in).

The post-mortem on Newson showed no medical reason to explain the crash. A cause has never been established, and theories include suicide, that he may have been distracted, or that he was affected by conditions such as transient global amnesia or akinesis with mutism. The subsequent inquest established that Newson had also inexplicably overshot platforms on the same route on two other occasions earlier in the week of the accident. Tests showed that Newson had a blood alcohol level of 80 mg/100 ml—the level at which one can be prosecuted for drink-driving, though the alcohol may have been produced by the natural decomposition process over four days at a high temperature.

In the aftermath of the crash, London Underground introduced a safety system that automatically stops a train when travelling too fast. This became known informally as Moorgate protection. Northern City Line services into Moorgate ended in October 1975 and British Rail services started in August 1976. After a long campaign by relatives of the dead, two memorials were unveiled near the station, one in July 2013 and one in February 2014.

Background

London Underground—also known as the Underground or the Tube—is a public rapid transit system serving London and some parts of the adjacent counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire.[1] The first line opened in 1863 and by 1975 the network contained 250 miles (400 km) of route track; that year three million people used the service each day.[2][3] The Tube was one of the safest methods of transport in Britain in 1975. Apart from suicides, there were only 14 deaths on the Underground between 1938 and 1975, 12 of which occurred in the 1953 Stratford crash.[2]

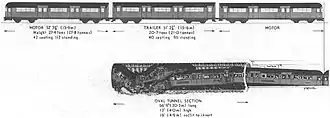

Moorgate station, in the City of London, was the terminus at the southern end of the Northern City Line, five stops and 2.6 miles (4.2 km) from the northern end at Drayton Park. Moorgate is an interchange between the Underground network and suburban overground services. The station contains ten platforms; numbers 7 to 10 are deep level, and numbers 9 and 10 are used for the Northern City Line service.[4] At the end of platform 9 in 1975 was a red warning light atop a post, situated in front of a 61-centimetre-high (2 ft) sand drag placed to stop overrunning trains. The drag was 11 metres (36 ft) long, of which 5.8 metres (19 ft) was on the tracks in front of the platform, and 5.2 metres (17 ft) was inside an overrun tunnel that was 20.3 metres (67 ft) long, 4 metres (13 ft) high and 4.9 metres (16 ft) wide. The tunnel had been designed to accommodate larger main line rolling stock and so was wider than the standard tube tunnel width of 3.7 metres (12 ft). A buffer stop, which had once been hydraulic, but had not been functioning as such for some time prior to the crash, was at the end of the tunnel, in front of a solid wall.[5][6] The approach to Moorgate from Old Street station, the stop prior to the terminus, was on a falling gradient of 1 in 150 for 196 metres (642 ft) before levelling out for 71 metres (233 ft) to platform 9; a scissors crossover was located just prior to platforms 9 and 10.[7] There was a speed limit of 40 miles per hour (64 km/h) on the line, and a limit of 15 miles per hour (24 km/h) on entry into Moorgate station.[8]

From November 1966 the Northern City Line ran 1938 rolling stock.[9] Weekly checks were made on the stock's brakes, doors and compressors; all equipment on the train was examined on a six-week basis and the cars were lifted from their bogies for a thorough examination once a year.[10][11]

Crash

On 28 February 1975 the first shift of the Northern City Line service was driven by Leslie Newson, 56, who had worked for London Transport since 1969 and been driving on the Northern City Line for the previous three months.[12] Newson was known by his colleagues as a careful and conscientious motorman (driver). On 28 February he carried a bottle of milk, sugar, his rule book, and a notebook in his work satchel;[lower-alpha 1] he also had £270 in his jacket to buy a second-hand car for his daughter after work.[lower-alpha 2] According to staff on duty his behaviour appeared normal. Before his shift began he had a cup of tea and shared his sugar with a colleague; he jokingly said to the colleague "Go easy on it, I shall want another cup when I come off duty".[15]

The first return trips of the day between Drayton Park and Moorgate, which started at 6:40 am, passed without incident. Robert Harris, the 18-year-old guard who had started working for London Underground in August 1974, was late and joined the train when it returned to Moorgate at 6:53 am; a driver waiting to go on duty took his place until his arrival. Newson and Harris made three further return trips before the train undertook its final journey from Drayton Park at 8:38 am, thirty seconds late. The train carried approximately 300 passengers; it was a Friday and, as it was the peak of rush hour, most of the travellers were commuters. As the exit from platform 9 was next to the overrun tunnel, the first two carriages were more popular with commuters and more full than the remaining four.[16] Although pupils from the nearby City of London School for Girls would normally have been on the service at that time, the pupils had a day's holiday as the school was in use for external examinations. The journalist Sally Holloway, in her history of the crash, observes that the number of casualties could have been higher if the girls had been attending school.[17]

After the train departed Old Street on its 56-second journey to Moorgate, Harris was bored and left his position at the guard's control panel—which contained the controls for the emergency brake—at the front of the rear carriage and walked to the back of the train to look for a newspaper. He did not find one and spent his time reading the advertisements on the walls at the rear of the carriage.[18]

On arrival at Moorgate at 8:46 am, the train, which comprised two units of three connected cars, did not slow. It was still under power and no brakes were applied; it passed through the station at 30–40 mph (48–64 km/h). The signalman on duty later reported that the train appeared to be accelerating as it passed along the platform. A passenger waiting to take the return journey stated that Newson appeared "to be staring straight ahead and to be somewhat larger than life". Tests were later done on trains entering platform 9 at slow speed. These showed that because of the station lighting, it was impossible to clearly see the driver's eyes.[19] Witnesses standing on the platform saw Newson sitting upright and facing forward, his uniform neat and still wearing his hat; his hands appeared to be on the train's controls as far as they could tell.[20]

The brakes were not applied and the dead man's handle was still depressed when the train entered the overrun tunnel, throwing up sand from the drag;[lower-alpha 3] when the driver's cab crashed into the hydraulic buffer, the carriage was separated from its bogie and the coachwork was forced into the end wall and the roof. The first 15 seats of the carriage were crushed into 0.61 metres (2 ft).[22] The second coach was forced under the rear of the first, which buckled at three points into the shape of a V with a tail, and had its rear forced into the tunnel roof. With the weight of the train piling up behind it, the 16-metre-long (52 ft) front coach was crushed to 6.1 metres (20 ft). The third car was damaged at both ends, more significantly at the leading end as it rode over the second.[23] Javier Gonzalez, a passenger who was travelling in the front carriage, described the moment the train crashed:

Just above my newspaper I saw a lady sitting opposite me and then the lights went out. I have the image of her face to this day. She died. As darkness came, there was a very loud noise of the crash, metal and glass breaking, no screams, all in the fraction of the second, one takes to breathe in. It was all over in no time.[24]

Forty-two passengers and the driver died; seventy-four people were treated in hospital for their injuries.[25] It was, and remains, the worst peacetime accident on the Underground.[26]

Rescue

The first call to the emergency services was received at 8:48 am; the London Ambulance Service arrived at 8:54 am[27] and the London Fire Brigade at 8:57 am.[28] At around the same time the City of London Police alerted nearby St Bartholomew's Hospital (Barts) that "a tube train had hit the buffers" at Moorgate, but there was no indication at that stage of the seriousness of the crash. A small assessment team comprising a casualty officer and a medical student was sent from the hospital; 15 minutes later a resuscitation unit was sent, although the hospital staff were still unaware of the scale of the problem.[29][lower-alpha 4] The City of London Police also contacted the medical unit of BP at Britannic House, Finsbury Circus. Dr Donald Dean and a team of two doctors and two nurses walked around to the station to assist, and were the first medical assistance at the scene. After assessing the situation, Dean realised that he did not have enough painkillers with him, or in BP stores, so he went to the Moorgate branch of Boots where the pharmacist gave him the shop's entire supply of morphine and pethidine.[31] The Fire Brigade undertook a brief inspection of the site and, once they saw what they were dealing with, the status was updated to a Major Accident event; additional ambulances and fire tenders were soon sent.[32] One of the doctors from Barts later described the scene:

The front carriage was an indescribable tangle of twisted metal and in it the living and the dead were heaped together, intertwined among themselves and the wreckage. It was impossible to estimate the number [of casualties] involved with any degree of accuracy because the lighting was poor, the victims were all tangled together, and everything was covered with a thick layer of black dust. Many of the victims were writhing in agony and were screaming for individual attention. It was obvious from an early stage that the main problem was the disentanglement of a heap of people, many of whom appeared to be in imminent danger of suffocation.[33]

By around 9:00 am the last casualty had been removed from the third carriage.[34] By 9:30 am Moorgate and many of the surrounding roads had been cordoned off to allow space for the co-ordination teams above ground to manage the flow of vehicles—particularly for ambulances taking casualties to hospitals. A message was sent from the London Fire Brigade headquarters to all fire stations in London; it estimated that there were still 50 people trapped and warned that "this incident will be protracted".[35] To make a clear passage through the wreckage for equipment, the emergency services and injured commuters, a circular route was organised through the carriages. Firemen cut holes in parts of the structure, including in the floors and ceilings of the carriages through which it was possible to move, even if it meant crawling through some areas.[36] At 10:00 am a medical team arrived from The London Hospital and set up a makeshift operating theatre on a platform near the triage team.[37]

Platform 9 was 21 metres (70 ft) underground, and fire and ambulance crews had to carry all the equipment they needed through the station and down to the scene of the accident. The depth at which they were operating, and the shielding effect of the soil and concrete, meant their radios could not get through to the surface. Messages and requests for further supplies were passed by runners, which led to mistakes: one doctor requested further supplies of the pain-killing gas Entonox, but by the time the request reached the surface, it had been garbled to "the doctor wants an empty box".[38][39] The fire brigade deployed a small team with "Figaro", an experimental radio system that worked in deep locations.[34] Working conditions for the emergency services became increasingly difficult throughout the day.[34] The crash had thrown soot and dirt into the air from the sand drag, and from between the two metal layers of the tube carriages. Everything was covered with a thick layer of the residue which was easily disturbed.[40] The lamps and cutting gear used by the fire brigade raised the temperature to over 49 °C (120 °F) and oxygen levels began to drop. In the deep lines at Moorgate, ventilation is produced by the piston effect, created by trains forcing air through the tube lines. With services stopped since the crash, no fresh air was reaching platforms 9 and 10.[41] A large electric fan was placed at the top of the escalators in an attempt to remedy the situation, but soot and dirt was disturbed and little draught was created; the machine was soon turned off.[42]

By 12:00 noon only five live casualties were left to be extracted;[39] by 3:15 pm only two were left: Margaret Liles, a 19-year-old Woman Police Constable (WPC), and Jeff Benton, who worked at the London Stock Exchange. They were in the front part of the first carriage at the time of the crash and ended up trapped together, pinned down under the girders of the carriage's structure.[43] The Fire Brigade worked for several hours to release Benton, but it became apparent that Liles needed to be removed first, which could only be done by amputating her left foot. She was finally removed from the wreckage after the procedure at 8.55 pm; Benton was removed at 10:00 pm.[44][45] As soon as Benton had been removed, all equipment was turned off and silence was ordered among the emergency services. Shouts were made for any people trapped to respond; there were no responses and the site medical officer declared that all the remaining bodies in the wreckage were dead.[46] During the day mouth-to-mouth resuscitation had been needed to save two people, and two victims died of crush syndrome soon after being released from the wreckage.[47] Benton also died of crush syndrome, in hospital on 27 March 1975, despite initially good progress.[48]

Aftermath

Clearing up

Work on removing the bodies and clearing the wreckage from the tunnel began after the last casualty had been removed. With no casualties remaining, the Fire Brigade were able to use flame cutting equipment. After the third carriage was cut free from the second, at 1:00 am on 1 March the third carriage began to be winched back down the track; as it began moving a body that no-one had seen fell from the wreckage and onto the track. According to Joseph Milner, the chief fire officer of the London Fire Brigade, the body gave "the first indication of how protracted would be the work ahead". Once the carriage had been removed, a doctor again checked for further signs of living casualties; none were found.[44]

The use of the flame cutting equipment had a detrimental effect on the atmosphere on the platform. Oxygen levels dropped from the norm of 21 per cent to 16 per cent and the smell of decomposition from the bodies trapped in the wreckage was noticed by workers.[49] Those working on the platform or tunnel were restricted to 20-minute spells working, followed by 40 minutes' recovery time on the surface. All workers had to wear gloves and masks; any cuts had to be reported, and no-one with a cut was allowed to be involved in the extrication of a body.[50] Temperatures improved after a company donated an air conditioning unit, which was installed at ground level, and the air piped down into the tunnel.[51]

During 1 and 2 March the wreckage of the second carriage was cut away in sections and winched free; clearance of the carriages continued round the clock until a break was forced by a telephoned bomb scare at 10:00 pm on 2 March, which forced the crews to evacuate the station.[52] The last passenger was removed from the front carriage at 3:20 pm on 4 March, which left only the driver's body. Gordon Hafter, London Underground's chief engineer, and Lieutenant Colonel Ian McNaughton, the Chief Inspecting Officer of Railways, examined the driver's cab;[lower-alpha 5] normally 91 centimetres (3 ft) deep, it had been crushed to 15 centimetres (6 in). They ascertained that Newson was at his controls, although his head had been forced through the front window.[55][56] Hafter reported his examination about Newson to the subsequent inquiry:

His left hand was close to, but not actually on the driver's brake handle and his right arm was hanging down to the right of the main controller. His head was to the left of the dead man's handle which had been forced upwards, beyond its normal travel, and was resting on his right shoulder.[57]

Newson's body was removed at 8:05 pm on 4 March;[58] the Fire Brigade cleared the remainder of the wreckage by 5:00 am on 5 March and handed control of the platform back to London Underground.[59] The rescue and clean-up operation involved the efforts of 1,324 firemen, 240 policemen, 80 ambulance men, 16 doctors and several nurses.[60]

Services on the line had been suspended on the day of the crash. A shuttle service between Drayton Park and Old Street was used from 1 March 1975 until normal traffic returned on 10 March.[25][61]

Investigation and inquiry

The post-mortem was undertaken on Newson by the Home Office pathologist Keith Simpson on 4 March 1975. He found no physical conditions, such as a stroke or heart attack, that would have explained the crash.[62] Initial findings showed no drugs or alcohol in Newson's bloodstream, and there was no evidence of liver damage from heavy drinking.[27]

On 7 March 1975 Anthony Crosland, the Secretary of State for the Environment, instructed McNaughton to undertake an investigation of the crash.[63] McNaughton's inquiry began on 13 March and was paused after a day and a half; during that time it was established that the mechanics of the train were in working order and that there were no known problems with Newson's health, although the results of pathological tests were still awaited. McNaughton said he was perplexed as to the causes of the crash, but that he would proceed with the next part of his inquiry, which was to undertake further enquiries and to consider measures so the accident could not be repeated.[64]

The coroner's inquest was held between 14 and 18 April 1975.[65] David Paul, the coroner, was unhappy that a government inquiry had already begun, as evidence was in the public domain, and could affect the inquest's jury. Sixty-one witnesses gave evidence.[66] An analysis of Newson's kidneys by the toxicologist Dr Anne Robinson showed his blood alcohol level at the time of the post-mortem was 80 mg/100 ml. Robinson stated that there were several biological processes that produced alcohol in the body after death, and it was not possible to reach a definite conclusion as to whether this was the result of consumption of alcohol or a product of the process of decomposition. She added "there are so many unknown factors here that it is difficult to be precise and definite. One has to make a number of assumptions", although she stated that it was likely that he had been drinking.[67] 80 mg/100 ml was—and, as at 2022, still is—the legal limit in England for driving.[68] It was the highest reading of four samples taken from Newson's body; the lowest was 20 mg/100 ml.[69] Newson's widow stated that her husband drank spirits only rarely; David Paul agreed that it was out of character with all he had heard, and agreed that further tests could be run on Newson's samples.[70] On the final day of the inquiry, Dr Roy Goulding, a specialist in the forensic examination of poisons, stated that while he reached the same results of 80 mg/100 ml, his conclusions differed from Robinson's; Goulding stated that as alcohol was naturally produced in the blood after death, it was not possible to confirm that Newson had been drinking prior to the crash. Several of Newson's colleagues reported that they had no suspicions that Newson had been drinking, and that his behaviour on the morning of the crash was normal. David Paul asked Simpson to comment on the findings relating to alcohol levels. He informed the coroner that "it is generally accepted that as much as 80 mg/100ml may make its appearance in a decomposing body after four days in a [relatively] high temperature".[27] The jury returned verdicts of accidental death.[71]

On 19 March a memorial service was held at St Paul's Cathedral, London, attended by 2,000 mourners, including representatives of the emergency services and Newson's widow and family.[60][72]

McNaughton published his report almost a year later, on 4 March 1976. He wrote that tests showed no equipment fault on the train, and that the dead man's handle had no defect. From X-rays it was clear that at the moment of the crash Newson's hand was on the dead man's handle. There were no electrical burns on his skin or clothing to indicate an electrical fault.[73] McNaughton observed that because of Harris's lack of experience, he could not have taken any action to stop the accident from happening, although he thought the young man "displayed himself as idle and undisciplined".[74] He concluded that "the accident was solely due to a lapse on the part of the driver, Motorman Newson".[75]

Given the inquest findings relating to alcohol in Newson's bloodstream, McNaughton examined the possibility that Newson was drunk. He received expert advice that even if Newson had drunk sufficient alcohol to achieve a blood alcohol level of 80 mg/100 ml, it would not account for the crash.[76] McNaughton also examined the possibility of suicide by Newson, but considered it unlikely, given other indications, including Newson's plans for purchasing a car later in the day and that he had driven the route without error for the preceding 21⁄2 hours.[77][78] During the inquest Harris testified that Newson had also overshot a platform three or four days before the accident, and a passenger had also reported a second overshoot by Newson that week. The suicide expert Bruce Danto stated of the overshoots, "that does not sound like misjudgment to me. That sounds like a man who is getting the feeling of how to run a train into a wall".[79]

McNaughton investigated the possibility that Newson may have been daydreaming or distracted to the point that he did not realise the train was entering Moorgate. McNaughton concluded that as the train went over the scissor crossing before the platform, it would have brought the driver to his senses. It was also likely that Newson would have realised his circumstances before the train hit the wall, and would have thrown his hands up in front of his face in a reflex action.[80] Medical evidence presented to the inquiry raised the possibility that the driver had been affected by conditions such as transient global amnesia or akinesis with mutism, where the brain continues to function and the individual remains aware, although not being able to move physically. There was no evidence to indicate either condition: to positively diagnose akinesis with mutism would depend on a microscopic examination of the brain, which was not possible because of decomposition, and transient global amnesia leaves no traces.[81] McNaughton's report found that there was insufficient evidence to say if the accident was due to a deliberate act or a medical condition.

I must conclude, therefore, that the cause of this accident lay entirely in the behaviour of Motorman Newson during the final minute before the accident occurred. Whether his behaviour was deliberate or whether it was the result of a suddenly arising physical condition not revealed as a result of post-mortem examination, there is not sufficient evidence to examine, but I am satisfied that no part of the responsibility for the accident rests with any other person and that there was no fault or condition of the train, track or signalling that in any way contributed to it.[82]

Legacy

London Underground services into Moorgate on the Northern City Line had previously been scheduled to be replaced by British Rail services from Welwyn Garden City and Hertford; the accident did not change the plan.[83] The last London Underground services on the Northern City Line ran into Moorgate on 4 October 1975 and British Rail services started in August 1976, having previously terminated at Broad Street station.[84]

When platform 9 reopened there had been changes introduced to aid drivers. The back wall of the tunnel was painted white and a large, heavy-duty buffer preceded the sand drag.[85] Shortly after the crash, London Underground imposed a speed limit of 10 mph (16 km/h) for all trains entering terminal platforms. Operating instructions were changed so that the protecting signal at terminal platforms was held at danger until trains approaching were travelling slowly, or had been brought to a stop, although this caused delays and operating problems.[86]

Moorgate protection

Since the death of a driver in 1971, when an empty stock train crashed into buffers in a tunnel siding near Tooting Broadway, London Underground had been introducing speed controls at such locations. By the time of the Moorgate crash, 12 of the 19 locations had the equipment installed. In July 1978, approval was given for Moorgate protection, Moorgate control or Trains Entering Terminal Stations (TETS) to be introduced at all dead-end termini on manually driven lines on the Underground system.[87][88]

At Moorgate's platform 9, three timed train stops were installed; the first at the scissors crossing, the second at the start of the platform and the third halfway down the platform. If the train passes any of these at more than 12.5 miles per hour (20.1 km/h) the emergency brake is applied.[89][90] Resistors were placed in the traction supply of trains, to prevent a train accelerating when entering the platform, although the value of these resistors had to be changed after installation. Relays switch the resistors out when the train is permitted to leave. The system was operational in all locations by 1984.[87]

This accident also led to changes in signalling. Previously it had always been standard policy for the last signal indication before a buffer-stop or bay platform to indicate "clear" (green) light to the train driver and "caution" (single-yellow) light if the platform was partly occupied. Following the Moorgate accident, signalling was changed to give an approach-controlled delayed yellow aspect when the line was clear to the buffer-stops and red plus a subsidiary aspect (two white lights at 45 degrees) when the line or platform was partly occupied.[91]

Memorials

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

In the south-west corner of Finsbury Square, 410 metres (450 yd) north of Moorgate station, a memorial lists those who died. Measuring 1.2 by 0.9 metres (4 ft × 3 ft), it was unveiled in July 2013 after a long campaign by relatives of the victims and supporters.[92][93] On 28 February 2014 a memorial plaque was unveiled by Fiona Woolf, the Lord Mayor of London, on the side of the station building, in Moor Place.[94]

In the media

In 1977 the BBC One programme Red Alert examined whether an accident like Moorgate could happen again.[95] The writer Laurence Marks, whose father died in the disaster, presented Me, My Dad and Moorgate, a Channel 4 documentary broadcast on 4 June 2006; he stated that he believed the crash was due to suicide by Newson.[96] In 2009 the BBC Radio 4 programme In Living Memory examined the causes of the crash,[97][98] and in 2015 Real Lives Reunited, aired on BBC One, recorded survivors meeting the firemen who cut them from the wreckage.[99]

Notes and references

Notes

- Newson used the notebook to record how to deal with train defects, and notes on how to be a better driver. He had covered both the notebook and manual in plastic to protect them, something the subsequent investigation thought "underlined the fact that Motorman Newson conducted himself in a most conscientious manner in respect of his job on the railway".[13]

- £270 equates to approximately £2100 in 2021, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[14]

- The dead man's handle must have continual downward pressure applied to it to run. If the pressure is reduced, the train's brakes are automatically applied.[21]

- The resuscitation unit consisted of an anaesthetic registrar, a surgical registrar and two nurses.[30]

- Hafter was a Chartered Engineer who had worked for London Underground for nearly thirty years. He oversaw maintenance of the company's rolling stock.[53] McNaughton had served with the Royal Engineers until 1963, specialising in transportation. He joined HM Railway Inspectorate the same year, and was made the Chief Inspecting Officer of Railways in 1972.[54]

References

- "An overview of the rail industry in Great Britain", Office of Rail and Road.

- Jordan 1975a, p. 11.

- "A brief history of the Underground", Transport for London.

- McNaughton 1976, pp. 2–3, paras 1 and 2.

- McNaughton 1976, pp. 3 and 21, paras 2 and 3.

- Medical staff of Three London Hospitals, The British Medical Journal, p. 278.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 3, para 2.

- Vaughan 2003, p. 21.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 166.

- Holloway 1988, pp. 94–95.

- McNaughton 1976, pp. 4 and 5, paras 16 and 18.

- Holloway 1988, pp. 7–8.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 8, para 44.

- Clark 2018.

- Vaughan 2003, p. 23; McNaughton 1976, p. 7, para 31.

- Foster 2015, p. 1; Milner 1975, p. i.

- Milner 1975, p. i; Holloway 1988, pp. 9 and 68.

- Vaughan 2003, p. 23; Holloway 1988, p. 11.

- Vaughan 2003, p. 24; Holloway 1988, p. 11; McNaughton 1976, pp. 8 and 9, paras 41 and 49.

- Vaughan 2003, p. 24.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 4, para 14.

- "Brake mystery in Tube disaster", The Guardian.

- Vaughan 2003, p. 25; McNaughton 1976, p. 5, para 20.

- "1975: Horror Underground". BBC.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 2, Introduction.

- "Remembering the 1975 Moorgate tube crash". London Fire Brigade.

- Vaughan 2003, p. 25.

- Milner 1975, p. i.

- Finch & Nancekiecill 1975, p. 666; Holloway 1988, pp. 14–15.

- Finch & Nancekiecill 1975, p. 666.

- Holloway 1988, pp. 14–15 and 18.

- Holloway 1988, p. 17.

- Finch & Nancekiecill 1975, p. 669.

- Milner 1975, p. ii.

- Holloway 1988, pp. 28–29.

- Milner 1975, pp. ii–iii.

- Holloway 1988, p. 29.

- Prosser 2008, p. 22.

- Finch & Nancekiecill 1975, p. 670.

- Holloway 1988, p. 23.

- Foster 2015, p. 2; Holloway 1988, p. 43; Tendler 1975, p. 3.

- Holloway 1988, p. 60.

- Holloway 1988, p. 63.

- Milner 1975, p. iv.

- Jordan et al. 1975, p. 1.

- Holloway 1988, pp. 66–67.

- Finch & Nancekiecill 1975, pp. 670 and 671.

- Holloway 1988, p. 66.

- Holloway 1988, p. 76.

- Milner 1975, p. vi.

- Holloway 1988, p. 86.

- Holloway 1988, pp. 74–75 and 85–86.

- Holloway 1988, p. 132.

- Holloway 1988, p. 90.

- Holloway 1988, p. 88.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 10, para 59.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 10, para 62.

- Milner 1975, p. viii.

- Holloway 1988, p. 89.

- Heather 2015.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 400.

- McHardy 1975, p. 6.

- "Tube Inquiry". The Guardian.

- Jordan 1975b, p. 5.

- Holloway 1988, p. 118.

- Leigh 1975, p. 2.

- "Moorgate Alcohol Finding", The Guardian.

- Tunbridge & Harrison 2017, p. 6.

- Pounder 1988, p. 87.

- Jones 1975a, p. 2.

- Jones 1975b, p. 2.

- Smith 1975, p. 6.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 12, para 75.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 16, para 103.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 15, para 96.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 13, paras 82 and 83.

- "Suicide by the Driver in Moorgate Tube Train Disaster is a Possibility, Inspector Says". The Times.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 15, para 99.

- Me, My Dad and Moorgate, 4 June 2006, Event occurs at 25:23–28:43.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 16, para 101.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 13, para 83.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 16, para 104.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 19, para 126.

- Blake 2015, pp. 11, 20 and 128.

- Nationwide, 4 March 1976, Event occurs at 18:25–19:00.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, p. 401.

- Croome & Jackson 1993, pp. 400–401.

- "Signals Passed at Danger on London Underground". Transport for London, pp. 1–2.

- McNaughton 1976, p. 19, para 128.

- Vaughan 2003, p. 26.

- Kichenside & Williams 1978.

- "Moorgate Tube crash memorial unveiled in Finsbury Square". BBC News.

- Gruner & Blunden 2013.

- Dean 2014.

- "Red Alert". BBC Genome Project.

- Gilbert 2006, p. 22.

- "In Living Memory". BBC Genome.

- "In Living Memory". BBC.

- "Real Lives Reunited". BBC.

Sources

Books

- Blake, Jim (2015). London's Railways 1967–1977: A Snap Shot in Time. Barnsley, S Yorks: Pen and Sword Transport. ISBN 978-1-4738-3384-5.

- Croome, Desmond; Jackson, Alan (1993) [1962]. Rails Through the Clay: A History of London's Tube Railways (2 ed.). London: Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-151-4.

- Day, John R.; Reed, John (2008). The Story of London's Underground. London: Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-316-7.

- Holloway, Sally (1988). Moorgate: Anatomy of a Railway Disaster. London: David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8913-3.

- Kichenside, G. M.; Williams, Alan (1978). British Railway Signalling (4th ed.). London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0898-1.

- McNaughton, Lt Col I. K. A. (4 March 1976). Report on the Accident that occurred on 28th February 1975 at Moorgate Station (PDF). London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-550398-6.

- Vaughan, Adrian (2003). Tracks to Disaster. Hersham, Surrey: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-2985-9.

Journals and magazines

- Finch, Philip; Nancekiecill, David (1975). "The Role of Hospital Medical Teams at a Major Accident". Anaesthesia. 30 (5): 666–676. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1975.tb00929.x. PMID 1190404.

- Foster, Stefanie (4 March 2015). "Moorgate...the unresolved tragedy". Rail. p. 2. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- Milner, Joseph (June 1975). "A Struggle for Life". Fire. 68 (840): i–viii.

- Medical Staff of Three London Hospitals (27 September 1975). "Moorgate Tube Train Disaster: Part I: Response of Medical Services". The British Medical Journal. 3 (5986): 727–729. doi:10.1136/bmj.3.5986.727. JSTOR 20406944. PMC 1674657. PMID 1174871.

- Pounder, Derrick (10 January 1988). "Dead Sober or Dead Drunk? May Be Hard to Determine". The British Medical Journal. 316 (7,125): 87. doi:10.1136/bmj.316.7125.87. JSTOR 25176680. PMC 2665406. PMID 9462305.

- Prosser, Tony (November 2008). "Going Underground: a Complete History of Tunnel Disasters". Fire. 101 (1310): 22–24.

- "Red Alert 2". Radio Times. No. 2800. 9 July 1977. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

News articles

- "1975: Horror Underground". BBC. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "Brake Mystery in Tube Disaster". The Guardian. 1 March 1975. p. 1.

- Dean, Jon (5 March 2014). "Plaque is Unveiled in Memory of Moorgate Tube Disaster victims". Islington Gazette.

- Gilbert, Gerard (2 June 2006). "Reviews: A Son Rises from the Darkness; The Weekend's TV". The Independent. p. 22.

- Gruner, Peter; Blunden, Mark (14 June 2013). "Memorial for victims of Tube crash that killed 43". London Evening Standard.

- Jones, Tim (18 April 1975a). "Toxicologist Stands by Moorgate Test Result". The Times. p. 2.

- Jones, Tim (19 April 1975b). "Moorgate Tube Crash Inquest Fails to Establish Whether Train Driver had Drunk Alcohol". The Times. p. 2.

- Jordan, Philip (1 March 1975a). "The Odds Against Disaster". The Guardian. p. 11.

- Jordan, Philip (15 March 1975b). "Moorgate Crash Inquiry Halted". The Guardian. p. 5.

- Jordan, Philip; McHardy, Anne; Smith, Alan; Tickell, Tom; Chippindale, Peter; Redden, Richard; Mogul, Rafiq; Mackie, Lindsay (1 March 1975). "13-hour struggle". The Guardian. p. 1.

- Leigh, David (15 April 1975). "Coroner Complains of Ministry Inquiry into Tube Crash". The Times. p. 2.

- McHardy, Anne (6 March 1975). "Healthy driver throws doubt on crash cause". The Guardian. p. 6.

- "Moorgate Alcohol Finding". The Guardian. 16 April 1975. p. 24.

- "Moorgate Tube Crash Memorial Unveiled in Finsbury Square". BBC News. 28 July 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Smith, Alan (20 March 1975). "Moorgate 'Ray of Light'". The Guardian. p. 6.

- "Suicide by the Driver in Moorgate Tube Train Disaster is a Possibility, Inspector Says". The Times. 5 June 1976. p. 2.

- Tendler, Stewart (1 March 1975). "Doctors Toil in Sweltering Heat to Help Victims". The Times. p. 3.

- "Tube Inquiry". The Guardian. 8 March 1975. p. 1.

Websites and television

- "A brief history of the Underground". Transport for London. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Clark, Gregory (2018). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Heather, Chris (28 February 2015). "The Moorgate Tube crash". The National Archives. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- "In Living Memory". BBC Genome. 28 November 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- "The 1975 Moorgate tube disaster". In Living Memory, series 11. BBC. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- Me, My Dad and Moorgate. Channel 4 (Television production). 4 June 2006.

- Nationwide. BBC One (Television production). 4 March 1976.

- "An Overview of the Rail Industry in Great Britain" (PDF). Office of Rail and Road. February 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "Real Lives Reunited". BBC. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- "Remembering the 1975 Moorgate tube crash". London Fire Brigade. 28 February 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- "Signals Passed at Danger on London Underground" (PDF). Transport for London. 20 July 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Tunbridge, Rob; Harrison, Katy (October 2017). "Fifty Years of the Breathalyser – Where Now for Drink Driving?" (PDF). Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

Further reading

- Jones, Richard (2015). End of the Line: The Moorgate Disaster. Bridlington, Yorkshire: Lodge Books. ISBN 978-1-3262-1141-7.

External links

- BBC News account of the accident

- Photos of the wreckage at the London Transport Museum