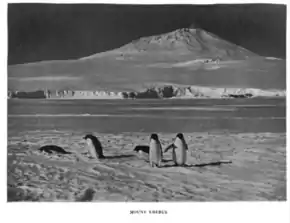

Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus ( /ˈɛrɪbəs/) is the second-highest volcano in Antarctica (after Mount Sidley), the highest active volcano in Antarctica, and the southernmost active volcano on Earth. It is the sixth-highest ultra mountain on the continent.[1] With a summit elevation of 3,794 metres (12,448 ft), it is located in the Ross Dependency on Ross Island, which is also home to three inactive volcanoes: Mount Terror, Mount Bird, and Mount Terra Nova.

| Mount Erebus | |

|---|---|

Mount Erebus | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,794 m (12,448 ft)[1] |

| Prominence | 3,794 m (12,448 ft)[1] Ranked 34th |

| Isolation | 121 km (75 mi) |

| Listing | Ultra |

| Coordinates | 77°31′47″S 167°09′12″E[2] |

| Geography | |

Mount Erebus Mount Erebus in Antarctica | |

| Location | Ross Island, Antarctica (claimed by New Zealand as part of the Ross Dependency) |

| Topo map | Ross Island |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 1.3 million years |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano (composite cone) |

| Volcanic belt | McMurdo Volcanic Group |

| Last eruption | Currently erupting |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1908 by Edgeworth David and party[3] |

| Easiest route | Basic snow & ice climb |

The volcano has been active since about 1.3 million years ago and has a long-lived lava lake in its inner summit crater that has been present since at least the early 1970s.

The volcano was the site of the Air New Zealand Flight 901 accident, which occurred in November 1979.

Geology and volcanology

Mount Erebus is the world's southernmost active volcano. It is the current eruptive centre of the Erebus hotspot. The summit contains a persistent convecting phonolitic lava lake, one of five long-lasting lava lakes on Earth. Characteristic eruptive activity consists of Strombolian eruptions from the lava lake or from one of several subsidiary vents, all within the volcano's inner crater.[4][5] The volcano is scientifically remarkable in that its relatively low-level and unusually persistent eruptive activity enables long-term volcanological study of a Strombolian eruptive system very close (hundreds of metres) to the active vents, a characteristic shared with only a few volcanoes on Earth, such as Stromboli in Italy. Scientific study of the volcano is also facilitated by its proximity to McMurdo Station (U.S.) and Scott Base (New Zealand), both sited on Ross Island around 35 km away.

Mount Erebus is classified as a polygenetic stratovolcano. The bottom half of the volcano is a shield and the top half is a stratocone. The composition of the current eruptive products of Erebus are anorthoclase-porphyritic tephritic phonolite and phonolite, which are the bulk of exposed lava flow on the volcano. The oldest eruptive products consist of relatively undifferentiated and nonviscous basanite lavas that form the low broad platform shield of Erebus. Slightly younger basanite and phonotephrite lavas crop out on Fang Ridge – an eroded remnant of an early Erebus volcano – and at other isolated locations on the flanks of Erebus. Erebus is the world's only presently erupting phonolite volcano.[6]

Lava flows of more viscous phonotephrite and trachyte erupted after the basanite. The upper slopes of Mount Erebus are dominated by steeply dipping (about 30°) tephritic phonolite lava flows with large-scale flow levees. A conspicuous break in slope around 3,200 m ASL calls attention to a summit plateau representing a caldera. The summit caldera was created by an explosive VEI-6 eruption that occurred 18,000 ± 7,000 years ago.[7] It is filled with small volume tephritic phonolite and phonolite lava flows. In the center of the summit caldera is a small, steep-sided cone composed primarily of decomposed lava bombs and a large deposit of anorthoclase crystals known as Erebus crystals. The active lava lake in this summit cone undergoes continuous degassing.

Following studies conducted in the early 1990's, it was found that Mount Erebus releases small amounts of gold crystals in the gases produced from the volcano; these crystals range in size from 20 to 60 micrometres. It is estimated that around 80 grams of gold are released by the volcano in this manner each day.[8]

Researchers spent more than three months during the 2007–08 field season installing an atypically dense array of seismometers around Mount Erebus to listen to waves of energy generated by small, controlled blasts from explosives they buried along its flanks and perimeter, and to record scattered seismic signals generated by lava lake eruptions and local ice quakes. By studying the refracted and scattered seismic waves, the scientists produced an image of the uppermost (top few km) of the volcano to understand the geometry of its "plumbing" and how the magma rises to the lava lake. [9][10] These results demonstrated a complex upper-volcano conduit system with appreciable upper-volcano magma storage to the northwest of the lava lake at depths hundreds of meters below the surface.

Ice fumaroles

Mt. Erebus is notable for its numerous ice fumaroles – ice towers that form around gases that escape from vents in the surface.[11] The ice caves associated with the fumaroles are dark, in polar alpine environments starved in organics and with oxygenated hydrothermal circulation in highly reducing host rock. The life is sparse, mainly bacteria and fungi. This makes it of special interest for studying oligotrophs – organisms that can survive on minimal amounts of resources.

The caves on Erebus are of special interest for astrobiology,[12] as most surface caves are influenced by human activities, or by organics from the surface brought in by animals (e.g. bats and birds) or ground water.[13] The caves at Erebus are at high altitude, yet accessible for study. Almost no chance exists of photosynthetic-based organics, or of animals in a food chain based on photosynthetic life, and no overlying soil to wash down into them.

They are dynamic systems that collapse and rebuild, but persist over decades. The air inside the caves has 80 to 100% humidity, and up to 3% carbon dioxide (CO2), and some carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen (H2), but almost no methane (CH4) or hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Many of them are completely dark, so cannot support photosynthesis. Organics can only come from the atmosphere, or from ice algae that grow on the surface in summer, which may eventually find their way into the caves through burial and melting. As a result, most micro-organisms there are chemolithoautotrophic i.e. microbes that get all of their energy from chemical reactions with the rocks, and that do not depend on any other lifeforms to survive. The organisms survive using CO2 fixation and some may use CO oxidization for the metabolism. The main types of microbe found there are Chloroflexota and Acidobacteriota.[14][15] In 2019, the Marsden Fund granted nearly NZ$1 million to the University of Waikato and the University of Canterbury to study the micro-organisms in the geothermal fumaroles.[16]

Named features

Mount Erebus is large enough to have several named features on its slopes, including a number of craters and rock formations.

Named craters located on Mount Erebus include Side Crater, a nearly circular crater named for its location on the side of the main summit cone, and Western Crater, named for the slope on which it sits.[17][18]

There are many rock formations on Mount Erebus. On the northwest upper slope of the active cone near a former exploration camp site, lava flow has formed a prominent outcropping called Nausea Knob, named for the nausea caused by elevation sickness.[19] Also on the northwest slope sits Tarr Nunatak, named by the New Zealand Geographic Board (NZGB) in 2000 after Sgt. L.W. Tarr, an aircraft mechanic with the New Zealand contingent of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition.[20] On the southwest rim of the summit caldera sits Seismic Bluff, named for a seismic station nearby.[21] The Cashman Crags are two rock summits at about 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) high on the west slope of Mount Erebus, 0.6 nautical miles (1.1 km) southwest of Hoopers Shoulder. The crags were named by the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names after Katharine Cashman,[22] United States Antarctic Research Program team member.[23]

History

Discovery and naming

Mount Erebus was discovered on 27 January 1841 (and observed to be in eruption),[24] by polar explorer Sir James Clark Ross on his Antarctic expedition, who named it and its companion, Mount Terror, after his ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror (which were later used by Sir John Franklin on his disastrous Arctic expedition). Present with Ross on HMS Erebus was the young Joseph Hooker, future president of the Royal Society and close friend of Charles Darwin. Erebus is a dark region in Hades in Greek mythology, personified as the Ancient Greek primordial deity of darkness, the son of Chaos.[25]

Historic sites

The mountain was surveyed in December 1912 by a science party from Robert Falcon Scott's Terra Nova expedition, who also collected geological samples. Two of the camp sites they used have been recognised for their historic significance:

- Upper “Summit Camp” site (HSM 89) consists of part of a circle of rocks, which were probably used to weight the tent valances.

- Lower “Camp E” site (HSM 90) consists of a slightly elevated area of gravel, as well as some aligned rocks, which may have been used to weight the tent valances.

They have been designated historic sites or monuments following a proposal by the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and the United States to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting.[26]

Climbing

Mount Erebus' summit crater rim was first achieved by members of Sir Ernest Shackleton's party; Professor Edgeworth David, Sir Douglas Mawson, Dr Alister Mackay, Jameson Adams, Dr Eric Marshall and Phillip Brocklehurst (who did not reach the summit), in 1908. Its first known solo ascent and the first winter ascent was accomplished by British mountaineer Roger Mear on 7 June 1985, a member of the "In the Footsteps of Scott" expedition.[27] On 19–20 January 1991, Charles J. Blackmer, an iron-worker for many years at McMurdo Station and the South Pole, accomplished a solo ascent in about 17 hours completely unsupported, by snow mobile and on foot.[28][29]

Robotic exploration

In 1992, the inside of the volcano was explored by Dante I, an eight legged tethered robotic explorer.[30] Dante was designed to acquire gas samples from the magma lake inside the inner crater of Mount Erebus to understand the chemistry better through the use of the on-board gas chromatograph, as well as measuring the temperature inside the volcano and the radioactivity of the materials present in such volcanoes. Dante successfully scaled a significant portion of the crater before technical difficulties emerged with the fibre-optic cable used for communications between the walker and base station. Since Dante had not yet reached the bottom of the crater, no data of volcanic significance was recorded. The expedition proved to be highly successful in terms of robotic and computer science, and was possibly the first expedition by a robotic platform to Antarctica.

Air New Zealand Flight 901

Air New Zealand Flight 901 was a scheduled sightseeing service from Auckland Airport in New Zealand to Antarctica and return with a scheduled stop at Christchurch Airport to refuel before returning to Auckland.[31] The Air New Zealand flyover service, for the purposes of Antarctic sightseeing, was operated with McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 aircraft and began in February 1977. The flight crashed into Mount Erebus on November 28, 1979, killing all 257 people on board. Passenger photographs taken seconds before the collision ruled out the "flying in a cloud" theory, showing perfectly clear visibility well beneath the cloud base, with landmarks 13 miles (21 km) to the left and 10 miles (16 km) to the right of the aircraft visible.[32] The mountain directly ahead was lit by sunlight shining from directly behind the aircraft through the cloud deck above, resulting in a lack of shadows that made Mount Erebus effectively invisible against the overcast sky beyond in a classic whiteout (more accurately, "flat-light") phenomenon.[33] Further investigation of the crash showed an Air New Zealand navigational error and a cover-up that resulted in about $100 million in lawsuits. Air New Zealand discontinued its flyovers of Antarctica. Its final flight was on February 17, 1980. During the Antarctic summer, snow melt on the flanks of Mount Erebus continually reveals debris from the crash that is visible from the air.[31]

Image gallery

Topographic map of Ross Island (1:250,000 scale)

Topographic map of Ross Island (1:250,000 scale)

Mount Erebus is in the lower left.

Mount Bird is in the upper left.

Mount Terra Nova is in the middle.

Mount Terror is in the right..jpg.webp) Aerial view of Mount Erebus craters

Aerial view of Mount Erebus craters Satellite picture of Mount Erebus showing glow from its persistent lava lake

Satellite picture of Mount Erebus showing glow from its persistent lava lake Mount Erebus in December 1955

Mount Erebus in December 1955

See also

- Charles Neider

- Coleman Peak

- Erebus Glacier

- Erebus Ice Tongue

- Ice Tower Ridge

- List of volcanoes in Antarctica

- Lower Erebus Hut – home of MEVO

- Volcanic Seven Summits#Volcanic Seven Second Summits

- Helo Cliffs, a prominent feature on the caldera

References

- "Mount Erebus". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- "Mount Erebus". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "Antarctic explorers". Australian Antarctic Division. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- Kyle, P. R., ed. (1994). Volcanological and Environmental Studies of Mount Erebus, Antarctica. Antarctic Research Series. Washington DC: American Geophysical Union. ISBN 0-87590-875-6. OCLC 1132108108.

- Aster, R.; Mah, S.; Kyle, P.; McIntosh, W.; Dunbar, N.; Johnson, J. (2003). "Very long period oscillations of Mount Erebus volcano". J. Geophys. Res. 108 (B11): 2522. Bibcode:2003JGRB..108.2522A. doi:10.1029/2002JB002101.

- Burgisser, Alain; Oppenheimer, Clive; Alletti, Marina; Kyle, Philip R.; Scaillet, Bruno; Carroll, Michael R. (November 2012). "Backward Tracking of Gas Chemistry Measurements at Erebus Volcano" (PDF). Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 13 (11). doi:10.1029/2012GC004243. S2CID 14494732.

- "VOGRIPA". www.bgs.ac.uk.

- Hecht, Jeff (7 September 1991). "Science: Antarctic gold dust". New Scientist. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- "Plumbing Erebus: Scientists use seismic technique to map interior of Antarctic volcano".

- Zandomeneghi, D.; Aster, R.; Kyle, P.; Barclay, A.; Chaput, J.; Knox, H. (2013). "Internal structure of Erebus volcano, Antarctica imaged by high-resolution active-source seismic tomography and coda interferometry". Journal of Geophysical Research. 118 (3): 1067–1078. Bibcode:2013JGRB..118.1067Z. doi:10.1002/jgrb.50073. S2CID 129121276.

- For photographs of ice fumaroles, see Ice Towers Archived 2015-01-01 at the Wayback Machine Mount Everest Volcano Observatory

- "Descent into a Frozen Underworld". Astrobiology Magazine. 17 February 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- AnOther (18 June 2015). "Mount Erebus: A Tale of Ice and Fire". AnOther. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- Tebo, Bradley M.; Davis, Richard E.; Anitori, Roberto P.; Connell, Laurie B.; Schiffman, Peter; Staudigel, Hubert (2015). "Microbial communities in dark oligotrophic volcanic ice cave ecosystems of Mt. Erebus, Antarctica". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 179. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00179. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 4356161. PMID 25814983.

- Wall, Mike (9 December 2011). "Antarctic Cave Microbes Shed Light on Life's Diversity". Livescience.

- Harris, Rosie (2019). "Micro-organisms in the volcanic vents of Erebus - a key to life on other planets?". Antarctic. 38 (3 & 4): 14–15. ISSN 0003-5327.

- "Side Crater". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- "Western Crater". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Nausea Knob". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Tarr Nunatak". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Seismic Bluff". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- The Royal Society: Katharine Cashman Retrieved 2021-05-10

- "Cashman Crags". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Ross, Voyage to the Southern Seas, vol. i, pp. 216–8.

- Hesiod, Theogony 116–124.

- "List of Historic Sites and Monuments approved by the ATCM (2013)" (PDF). Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- Mear, Roger; Swan, Robert; Fulcher, Lindsay (1987). A Walk to the Pole: To the Heart of Antarctica in the Footsteps of Scott. pp. 95–104. ISBN 978-0-517-56611-4. OCLC 16092953.

- Wheeler, Sara (1998). Terra Incognita. ISBN 9780679440789.

- Johnson, Nicholas (2005). Big Dead Place. ISBN 9780922915996.

- Wettergreen, David; Thorpe, Chuck; Whittaker, Red (December 1993). "Exploring Mount Erebus by Walking Robot". Robotics and Autonomous Systems. 11 (3–4): 171–185. doi:10.1016/0921-8890(93)90022-5. S2CID 1190583.

- Holmes, Paul (2011). Daughters of Erebus. Hodder Moa. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-86971-250-1. OCLC 740446014.

- Royal Commission Report, para 28

- Royal Commission Report, para 40(a)

- General

- LeMasurier, W. E.; Thomson, J. W., eds. (1990). Volcanoes of the Antarctic Plate and Southern Oceans. American Geophysical Union. ISBN 0-87590-172-7.

- Sims, Kenneth W. W.; Aster, Richard C.; Gaetani, Glenn \; Blichert-Toft, Janne; Phillips, Erin H.; Wallace, Paul J.; Mattioli, Glen S.; Rasmussen, Dan; Boyd, Eric S. (2021). "Mount Erebus" (PDF). Geological Society of London, Memoirs. doi:10.1144/m55-2019-8. eISSN 2041-4722. ISSN 0435-4052. S2CID 233522516.

External links

- A picture from space of the lava lake at the summit of Mount Erebus

- Erebus glacier tongue

- A panoramic view from the summit of Mount Erebus

- Video of Mount Erebus erupting in 2005

- List of published research about Mount Erebus, maintained by Mount Erebus Volcano Observatory

![]() Mount Erebus travel guide from Wikivoyage

Mount Erebus travel guide from Wikivoyage