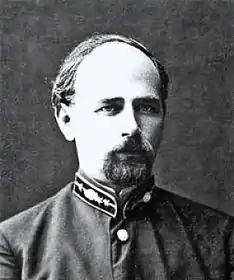

Mykola Leontovych

Mykola Dmytrovych Leontovych (13 December [O.S. 1 December] 1877 – 23 January 1921; Ukrainian: Микола Дмитрович Леонтович; also Leontovich) was a Ukrainian composer, conductor, ethnomusicologist and teacher. His music was inspired by Mykola Lysenko and the Ukrainian National Music School. Leontovych specialised in a cappella choral music, ranging from original compositions, to church music, to elaborate arrangements of folk music.

Mykola Leontovych | |

|---|---|

| Микола Леонтович | |

| |

| Born | Mykola Dmytrovych Leontovych 13 December 1877 Monastyrok, Podolia, Russian Empire today Ukraine |

| Died | 23 January 1921 (aged 43) Markivka, Podolian Governorate, Ukrainian SSR |

| Occupation |

|

Leontovych was born and raised in the Podolia province of the Russian Empire (now in Ukraine). He was educated as a priest in the Kamianets-Podilskyi Theological Seminary and later furthered his musical education at the Saint Petersburg Court Capella and private lessons with Boleslav Yavorsky. With the independence of the Ukrainian state in the 1917 revolution, Leontovych moved to Kyiv where he worked at the Kyiv Conservatory and the Mykola Lysenko Institute of Music and Drama. He is recognised for composing Shchedryk in 1904 (which premiered in 1916), known to the English-speaking world as Carol of the Bells or Ring, Christmas Bells. He is known as a martyr in the Eastern Orthodox Ukrainian Church, where he is also remembered for his liturgy, the first liturgy composed in the vernacular, specifically in the modern Ukrainian language. He was assassinated by a Soviet agent in 1921.

During his lifetime, Leontovych's compositions and arrangements became popular with professional and amateur groups alike across the Ukrainian region of the Russian Empire. Performances of his works in western Europe and North America earned him the nickname "the Ukrainian Bach" in France. Apart from his very popular Shchedryk, Leontovych's music is performed primarily in Ukraine and the Ukrainian diaspora.

Biography

Early life and education

Mykola Leontovych was born on December 13 [O.S. 1 December] 1877 in the Monastyrok community, near the village of Selevyntsi, in the Podolia province of Ukraine (then a part of the Russian Empire).[1] His father, grandfather, and great grandfather were village priests.[2] His father, Dmytro Feofanovych Leontovych, was skilled at singing and playing cello, double bass, harmonium, violin, and guitar, in addition to directing a school choir. Leontovych received his first musical lessons from him. His mother, Mariya Yosypivna Leontovych, was also a singer.[3][4]

Other members of Leontovych's family also grew up to have careers in music. His younger brother became a professional singer, his sister Mariya studied singing in Odesa, his sister Olena studied fortepiano at the Kyiv Conservatory, and his sister Victoriya also knew how to play several musical instruments.[3]

In the summer of 1879, Dmytro Leontovych was moved to a new parish located in the village of Shershni in suburbs of Bar, Ukraine in Bar's district, where he would spend his childhood.[4] Then, in 1887, Leontovych was admitted to Nemyriv gymnasium. Due to financial problems a year later, however, his father transferred him to the Sharhorod Spiritual Beginners School, whose pupils received full financial support.[5] At the school, Leontovych mastered singing, and was able to freely read difficult passages from religious choral texts.[4]

Theological seminary

In 1892, Leontovych began his studies at the theological seminary in Kamianets-Podilskyi, which both his father and grandfather had attended. His younger brother Oleksandr was enrolled as well, graduating two years after Mykola.[4]

During his studies there, Leontovych continued to advance his skills on the violin and learnt to play a variety of other instruments.[2] He also participated in the seminary's choir, and when an orchestra was formed during his third year of study, Leontovych joined, playing the violin until his graduation. Leontovych studied music theory and started writing choral arrangements as a student at the seminary.[4]

When the seminary's choir director died, the school administration requested that Leontovych take over this position. As the conductor of the choir, Leontovych added secular music to the repertoire of traditional church music. This included Ukrainian folk songs arranged by Mykola Lysenko, Porfyriy Demutskiy, and himself.[4] Leontovych graduated from the Kamianets-Podilskiy Theological Seminary in 1899 and broke the family tradition by becoming a music teacher instead of a priest.[3][4]

Early musical career and family

At the time, a career in music in Ukraine meant having an unstable income, causing Leontovych to seek employment wherever he could find it.[6] Leontovych worked in Kyiv, Yekaterinoslav, and Podolia guberniyas over the next few years in order to remain gainfully employed.[4][7] His first position after graduating was in a secondary school in the village of Chukiv (present-day Vinnytsia Oblast) as a vocal and maths teacher.[4] During this time, Leontovych continued to transcribe and arrange folk songs. He completed his First Compilation of Songs from Podolia and began working on his second compilation.[4] He also inspired the children at the school to sing in the choir and play in the orchestra. He would later write a book about this as a professor at the Kyiv Conservatory, titled Як я організував оркестр у сільській школі (How I Organised an Orchestra in a Village School).[8]

After several conflicts with the school's administration, Leontovych got a new job as a teacher of church music and calligraphy at the Theological College in Tyvriv.[4] Besides working with the college choir, Leontovych organised an amateur orchestra that often performed at college events. As he did earlier with choirs, Leontovych included arrangements of folk songs among the usual religious works sung in theological schools. These included arrangements by Mykola Lysenko, his own choral arrangements of folk songs, and entirely original works. One such work was based on a poem by Taras Shevchenko titled Зоре моя вечірняя (Oh My Evening Star).[4]

During this period, Leontovych met a Volhynian girl named Claudia Feropontivna Zhovtevych, whom he married on 22 March 1902. The young couple's first daughter, Halyna, was born in 1903.[4] They later had a second daughter named Yevheniya.[2]

Financial hardships prompted Leontovych to accept an offer to move to the city of Vinnytsia to instruct at the Church-Educators' College. Again, he organised a choir and, later, a concert band, with which he performed both secular and spiritual music. In 1903, he published his Second Compilation of Songs from Podolia which he dedicated to Mykola Lysenko.[4]

In 1903 and 1904, during his vacation from the Church-Educators' College, Leontovych travelled to St. Petersburg. There, he attended lectures held at the St. Petersburg Court Capella, which was associated with composers Maksym Berezovsky, Dmytro Bortniansky, and Mikhail Glinka. He studied music theory, harmony, and polyphony with Semen Barmotin, and choral performance with Aleksey Puzyrevskiy, both of whom were well known at the time.[4][8] On 22 April 1904, he earnt his credentials as a choirmaster of church choruses.[1][8]

Again, disputes with the administration of the college resulted in Leontovych's seeking new employment.[4] In the spring of 1904, he left Podolia and moved to the Donbas province in eastern Ukraine, where he became a teacher of vocal and instrumental music in a school for railroad workers' children.[8] During the Russian Revolution of 1905, Leontovych organised a choir of workers that performed in meetings. These works included arrangements of Ukrainian, Jewish, Armenian, Russian, and Polish folk songs.[4] Leontovych's activity caught the attention of local authorities, and in the spring of 1908, he was forced to move back to his native Podolia province to the city of Tulchyn.[8]

Tulchyn period

Leontovych's move to Tulchyn marked the beginning of a period of compositional maturity and major artistic achievements in the life of the composer.[4] In Tulchyn, Leontovych taught vocal and instrumental music at the Tulchyn Eparchy Women's College to the daughters of village priests.[8] There, he met composer Kyrylo Stetsenko who was a student of Mykola Lysenko and also specialised in choral music. Stetsenko lived in a nearby village at the time where he was working as a priest, and their acquaintance developed into a lasting friendship that influenced Leontovych's music.[4] Stetsenko was the first critic of Leontovych's music, saying, "Leontovych is a famous music expert from Podolia. He recorded many folk songs... These songs are harmonised for mixed choir. These harmonisations have revealed the author to be a great expert of both choral singing and theoretical studies".[2] Leontovych also transitioned to more renowned music during his choir performances, such as Russian composers Mikhail Glinka, Alexey Verstovsky, and Peter Tchaikovsky in addition to Ukrainian composers Mykola Lysenko, Kyrylo Stetsenko, and Petro Nishchynskyi.[8]

From 1909, he studied under musical theoretic Boleslav Yavorsky,[5][8] whom he periodically visited in Moscow and Kyiv over the next twelve years. Leontovych also became involved with theatrical music in Tulchyn and its community life by taking charge of a local organisation called Prosvita, meaning "enlightenment".[4][8]

This period in his career was among the most productive, as he created numerous choral arrangements. These included his famous Shchedryk, as well as Піють півні (The Roosters are Singing), Мала мати одну дочку (A Mother had One Daughter), Дударик (Little Dudka Player), Ой зійшла зоря (Oh, the Star has Risen), amongst others. In 1914, Stetsenko convinced Leontovych to have his music performed by the student choir of the Kyiv University under the leadership of Alexander Koshetz. On 26 December 1916, the performance of his arrangement of Shchedryk brought Leontovych great success from the public in Kyiv and raised the interest of intellectuals.[8]

Career in Kyiv

During the October Revolution and the establishment of the Ukrainian People's Republic in 1918, Leontovych relocated without his family to Ukraine's capital Kyiv, where he was active as both a conductor and composer. Several of his pieces gained popularity among professional and amateurs groups alike, who added them to their repertoire. In the beginning of 1919, the rest of his family also relocated to Kyiv. During this period, Leontovych also began teaching choir conducting alongside Hryhoriy Veryovka at the Kyiv Conservatory, and also taught at the Mykola Lysenko Institute of Music and Drama.[8] Leontovych was one of the organisers of the first Ukrainian State Orchestra. He participated in the founding of the Ukrainian Republic Capella of which he was the commissioner.[4]

Move-back to Tulchyn and assassination

During the conquest of Kyiv on 31 August 1919, the Denikin Army persecuted the Ukrainian intelligentsia.[9] Fleeing persecution, Leontovych returned to Tulchyn with his family. There, he started the city's first music school, since the college where he had worked was closed down by the Bolsheviks. He also began to work on his first major symphonic work, the opera Na Rusalchyn Velykden' (On the water nymph's Great Day).[8]

During the night of 22–23 January 1921, Mykola Leontovych was murdered by Chekist (Soviet state security) agent Afanasy Grishchenko. Leontovych was staying at the home of his parents, whom he was visiting for the Eastern Orthodox Feast of the Nativity (25 December in the Julian calendar, which, in the Gregorian calendar, adopted by the USSR only in 1918, falls in January). The undercover Chekist had also asked to stay the night at the house and shared a room with Mykola. At dawn he shot the composer (who died of blood loss a few hours later) after robbing his family.[4][8][10][11]

Several facts point to a political motive behind the assassination.[11][12] Leontovych's participation in the independence movement, such as commissioning Ukrainian Republic Capella, aimed at promoting Ukraine as an independent state, earned him many enemies. His older daughter Halyna later recalled her father saying, shortly before his death, that he had documents to leave the country for Romania, and that he had these documents with him among his sheet music during a concert. However, after returning from tea following the concert, Leontovych noticed that someone had gone through his papers.[12] His plans to leave the country, along with the fact that he was killed by a Soviet agent, also indicate political reasons for his death.[11][12]

Character

Mykola Leontovych was highly critical of himself. According to his first biographer Oles' Chapkivskyi, a contemporary of the composer, Leontovych would sometimes work on one choral setting without letting anyone else see it for up to four years.[3] After the publication of his Second Compilation of Songs from Podolia, he changed his mind and was not fully satisfied with it, and as a result he bought all 300 copies and had them destroyed.[8]

Chapkivskyi also described Leontоvych as having a shy personality, saying "He abstained from fame, feared attention and advertisement."[n 1] On the other hand, Chapkivskyi claimed that Leontovych's jealousy, fear of competition, and fear of non-acceptance from the established musical society, caused the music of Leontovych to be little known.[13]

Zynoviy Yaropud of the Kamianets-Podilskyi State Pedagogical University writes that "all of [Leontovych's] contemporaries called him a quiet, gentle person. He was not an active leader of the national-revolutionary movement, which revealed in the years of 1917–1921 a whole handful of prominent fighters for the Ukrainian republic,"[13][n 2] revealing that the composer was politically quiet, but not indifferent.

Leontovych's friend, O. Buzhanskiy, recalls that the composer was "always full of humour; spoke so that everyone was laughing to tears, but he remained serious and stayed calm." Stetsenko also described Leontovych to be a "witty storyteller" and that his students at the Church Educator's School in Tulchyn were "in love with him" because of his storytelling.[12]

Religious views

Mykola Leontovych grew up in a highly religious environment. He was a member of the Eastern Orthodox Church, descended from a line of village priests. He was also a graduate of the Podollia Theological Seminary in Kamianets-Podilskyi, which, for the most part, trained Orthodox Christian clergy.[3]

As a person with a professional theological education, Leontovych kept up with the movement of the establishment and recognition of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, which was reestablished in 1918. The composer's output during this period became rich in new sacred music, following the examples of Kyrylo Stetsenko (a close friend of Leontovych's, also an orthodox priest and composer[14]) and Alexander Koshetz. Leontovych's works form this time included На воскресіння Христа (On the Resurrection of Christ), Хваліте ім’я Господнє (Praise ye the Name of the Lord), and Світе тихий (Oh Quiet Light), among others. A milestone in the development of Ukrainian spiritual music was the composition of his liturgy, which was first performed in the St. Nicholas Military Cathedral at the Kyiv, Pechersk on 22 May 1919.[8]

Commemoration

On 1 February 1921, nine days after Leontovych's death, a large number of artists, professors, and students of the Mykola Lysenko Institute of Music and Drama in Kyiv gathered to commemorate him, as is expected according to Christian tradition. They established the Committee for the Memory of Mykola Leontovych, which later became the All-Ukrainian Mykola Leontovych Music Society, and promoted Ukrainian music until 1928.[8]

Ukrainian writer and politician of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Pavlo Tychyna, was an admirer of Leontovych and wrote about the composer's death in prose. Poets Maksym Rylskyi and Mykola Bazhan also dedicated poetry to him.[13]

The name of Leontovych is carried by musical groups, such as the Leontovych Bandurist Capella, and by educational institutions such as the Vinnytsia College of Arts and Culture. Streets in Kyiv and other cities have been named after him. There is a memorial museum dedicated to him in the city of Tulchyn, and another was established in 1977 in the village of Markivka where he was buried.[13][15]

In 2002, to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the composer's birth, the city of Kamianets-Podilskyi held an all-Ukrainian scientific conference entitled "Mykola Leontovych and Modern Education and Science," with guests from the Ukrainian ministry of education and science, the Ukrainian composers' Union, and many local authorities. During this event, the city held a ceremonial opening of a memorial plaque to the composer, placed next to the old building formerly used by the Podollia Theological Seminary.[3]

Music

Mykola Leontovych specialised in a cappella choral music.[16] He is remembered today mostly through the musical works he left behind, which include over 150 choral compositions. These range from artistic arrangements of folk songs, religious works (including his liturgy), cantatas, and choral compositions set to the words of various Ukrainian poets.[1] His two most famous works are the choral miniatures Schedryk and Dudaryk.[16]

Leontovych also commenced work on an opera (Na rusalchyn velykden’ – On the Water Nymph's Easter) based on Ukrainian myths and the works of Borys Hrinchenko. By the end of 1920, he had finished the first of three acts. However, Leontovych was murdered before he could complete the opera. Attempts to complete and edit the opera were made by Ukrainian composer Mykhailo Verykivsky.[17] Composer Myroslav Skoryk and poet Diodor Bobyr used the musical material of the unfinished opera to make a one-act operetta; this premiered in 1977 at the Kyiv State Opera and Ballet Theatre, one hundred years after Leontovych's birth. The North American premiere took place in Toronto on 11 April 2003.[7]

One of the largest influences in Mykola Leontovych's music is that of Mykola Lysenko,[16] who is considered "the father of Ukrainian classical music".[18][19] Leontovych admired Lysenko's music ever since he was a student at the Kamianets-Podilskyi Theological Seminary, when he had the seminary's choir perform the composer's music. Since then, he would perform Lysenko's music in concerts wherever he worked.[4]

Shchedryk/Carol of the Bells

Mykola Leontovych's Shchedryk is his most well-known piece. In its English version as a Christmas carol, it is known as the holiday favourite Carol of the Bells.[1][2][4][16] It is famous for its four-note ostinato motif and has been arranged over 150 times since 2004.[1] The original Ukrainian text of Shchedryk used hemiola, a shifting of accents within each measure between 6/8 and 3/4, which is lost in the English versions. The most popular English adaptation was composed in 1936 by Peter J Wilhousky who was influenced by the culture of his Eastern European parents and the traditional Christian story of carols ringing out at the birth of Jesus, although other English adaptations of the song were also made in 1947 by M. L. Holman, 1957, and 1972.[20]

The song has been used many times in the soundtracks for films and television. For example, it was used in the box office hits The Santa Clause[21] and Home Alone,[22] Will Vinton's award-winning A Claymation Christmas Celebration,[23] and as a parody called Carol of the Meows in The O.C.'s episode "The Chrismukkah That Almost Wasn't".[24] A modernised version of Carol of the Bells was played in The Office. It has also been arranged and performed by many groups, regardless of singing style or genre, ranging from classical (Vienna Boys Choir),[25] to traditional music groups (Celtic Woman),[26] to pop singers and groups (Jessica Simpson[27] and Destiny's Child[28]).

Musical style

Leontovych had an original style. Many of his works have "deft use of imitative counterpoint and impressionistic harmony."[16] He had a strong desire for his music to arouse the senses, especially sight, saying, "I'm interested in which colours you used for high tones, and which for the low ones. I myself often think about that, to combine sound and colour."[n 3][29]

His choral compositions feature rich harmony, vocal polyphony, and imitation. His earlier choral arrangements of folk songs were primarily strophic arrangements of the melody. As the composer gained more experience, the structure of his choral compositions and arrangements of folk songs became more frequently intertwined with text.[1]

Leontovych arranged many Ukrainian folk songs, creating artistically independent choral compositions based on their melodies and lyrics. He followed the traditions of improvisation of Ukrainian kobzars, who would interpret every new strophe differently. He also employed humming and the variability in timbre of singers' voices as techniques in reaching a desired emotional or sensual effect.[29]

A central topic of Leontovych's work is choral music about everyday life. His music frequently reflect actual actions and events. An example of this is his shchedrivka Ой там за горою (Oh there behind the Mountain) in which a tenor initially starts the song with a solo and the rest of the voices of the choir gradually come in, reflecting carolling when new groups of singers join in. Then, a switching of parts begins between different groups of the choir, recreating the clamorous atmosphere of the New Year's Eve.[29]

Reception and popularity

For most of his career, Leontovych kept his music to himself, only performing it during his own concerts. This was because of the composer's highly self-critical and shy personality.[13] Leontovych's first critic was his friend and fellow priest and composer Kyrylo Stetsenko, who described him to be "a great expert of both choral singing and theoretical studies".[2] He also convinced Leontovych to publish his music and have it performed by the Kyiv University.[4]

The successful debut of "Shchedryk" earnt Leontovych popularity among specialists and fans of choral music in Kyiv.[4] Leontovych's mentor-turned-coworker at the Kyiv Conservatory, Boleslav Yavorsky, also positively evaluated his newly written works.[4] During another concert, Leontovych's Lehenda, set to a poem by Mykola Voronyi, gained great popularity.[30]

After reviewing Leontovych's Second Compilation of Songs from Podolia, Lysenko wrote: "Leontovych has an original, illustrious gift. In his arrangements I found separate passages, movement of voices, which later developed in an ingeniously weaved musical network."[12][n 4]

The increase in popularity of Leontovych's music was aided by the head of the Ukrainian National Republic, Symon Petliura, who created and sponsored two choirs that would promote the awareness of and the culture of Ukraine.[31] One choir headed by Kyrylo Stetsenko toured across Ukraine, while the Ukrainian Republic Capella headed by Alexander Koshetz toured Europe and the Americas.[32] Performances by the Ukrainian Republic Capella made Leontovych known throughout the western world. In France, Leontovych earned the nickname, "Ukrainian Bach".[2][3][4][13] On 5 October 1921, the Capella performed Shchedryk in the Carnegie Hall in New York City. In 1936, ethnically Ukrainian Peter J. Wilhousky, who worked for Radio NBC, wrote his own lyrics for the song, which became known as the Carol of the Bells.[13]

Apart from Shchedryk, or the Carol of the Bells, Leontovych's music is currently performed mostly in Ukraine and few recordings are dedicated exclusively to him.[16] The Ukrainian diaspora remember him and perform his works. For example, the Oleksandr Koshyts Choir based in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, performs music of Ukrainian composers including Leontovych and have made a recording of his music.[33]

See also

- List of Ukrainian composers – see other Ukrainian composers of the same period

- Musical nationalism

Notes

- Original text: "боявся галасу", in which боявся=he feared, галасу=of -noise, -clamor, -commotion, -hustle and bustle. In other words he did not want all of the attention that came with fame

- Original text: "всі його сучасники називали тихою, лагідною людиною. Він не був активним лідером національно-революційного руху, який вияскравив у 1917–1921 роки ціле гроно видатних борців за Українську республіку" (tr. "All his contemporaries called him a quiet, gentle man. He was not an active leader of the national-revolutionary movement, which in 1917-1921 sparked a whole bunch of outstanding fighters for the Ukrainian Republic.")

- Original text: "Мене цікавить, які кольори ви використали для високих тонів, а які для низьких. Я сам часто думаю над тим, щоб поєднати звук і колір." (tr. "I'm interested in which colors you used for the highs and which for the lows. I often think about combining sound and color.")

- Original text: "Леонтович має оригінальний, яскравий дар. Я знайшов у цих обробках самостійні ходи, рух голосів, які потім розвивалися в геніально сплетену музичну мережку" (tr. "Leontovich has an original, bright gift. I found in these arrangements independent moves, the movement of voices, which then developed into an ingeniously woven musical network.")

References

- Wytwycky, Wasyl. "Leontovych, Mykola". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- "МИКОЛА ЛЕОНТОВИЧ - БАХ У ХОРОВІЙ МУЗИЦІ" [MYKOLA LEONTOVYCH - BACH IN CHOIR MUSIC] (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "До 125-річчя від дня народження Миколи Дмитровича ЛЕОНТОВИЧА" [To the 125th anniversary of the birth of Mykola Dmytrovych LEONTOVYCH]. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Monthly Newsletter of the Tylchyn Centralized Library System Archived 31 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Ukrainian)

- "Leontovych, Mykola Dmytrovych". UKRainskyi Obyednannyi Portal (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- РЕКВІЄМ ПО ЛЕОНТОВИЧУ (Requiem about Leontovych) Archived 18 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Article by Olga Melnyk on 18–31 December 2008 edition of the Ukrainian Gazette. Discusses "тривожні часи" (rough times) and poverty that Leontovych and others had to live through during that time.

- Solomon, Sonia (30 March 2003). "Toronto choirs to pay tribute to Mykola Leontovych". The Ukrainian Weekly. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Kuzyk, Valentyna. "Mykola Dmytrovych LEONTOVYCH". National Organization of Composers of Ukraine (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- Путін і Денікін – одна дорога з України (Putin and Denikin – one road of Ukraine) Article by Vasyl Zilhalov on radiosvoboda.org. Published 25 May 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2011 (in Ukrainian)

- "Николай Леонтович " НотОбоз – большой нотный архив. Ноты для балалайки, баяна, кларнета, ноты песен... Ноти" [Nikolai Leontovich "NotOboz - a large musical archive. Sheet music for balalaika, button accordion, clarinet, sheet music ...] (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Вбивця стріляв у сплячого композитора" [The killer was shooting at the sleeping composer]. the newspaper '20 Minutes'.

- "«Щедрик» Леонтовича лунає по всьому світу" [Leontovych's "Shchedryk" echoes through the entire world]. pravda.if.ua.(in Ukrainian) Article published 20 January 2011 in Halychyna Gazette

- "Микола Леонтович - Бах у хоровій музиці" [Mykola Leontovych - Bach in choral music]. www.aratta-ukraine.com.

- "Кирило Григорович Стеценко – композитор, диригент, священик, громадський діяч" [Kyrylo Hryhorovych Stetsenko - composer, conductor, priest, public figure]. www.ar25.org.

- "Музей Леонтовича" [Museum of Leontovych] (description of Leontovych Museum in the village of Markivka). t-komp.narod.ru.

- Mykola Dmytrovich Leontovych About/Bio – ClassicalArchives.com

- "115 років від дня народження М.І.Вериківського (1896–1962)..." [115 years since the day of birth of M.I.Verykivsky...]. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011. biography of Verekivsky (in Ukrainian)

- The music of Mykola Lysenko Duma Music, Inc.

- Kononenko, Natalie (2003). "Preview of Taras Filenko and Tamara Bulat's The World of Mykola Lysenko: Ethnic Identity, Music, and Politics in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Ukraine". Western Folklore. 62 (4): 301–303. JSTOR 1500324. with this reference.

- "SEAN89BOWIECAT" (pseudonym) (2 December 2012). "Carol of the Bells". Carols.net. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- The Santa Clause (1994) – Soundtracks imdb.com

- Home Alone (1990) – Soundtracks imdb.com

- A Claymatin Christmas (1987) (TV) – Soundtracks imdb.com

- "Carol of the Meows". 16 November 2004.

- CD Universe Track listing of Vienna Boy's Choir Album Christmas Greetings From The Vienna Boys Choir

- iTunes Track listing Celtic Woman's Album Holidays & Hits: Christmas Celebration / The Greatest Journey

- iTunes Track listing of Jessica Simpson's 2010 Album Happy Christmas

- iTunes Track Listing of Destiny's Child's Album 8 Days of Christmas

- "Леонтович Микола Дмитрович - 100 видатних українців" [Leontovych Mykola Dmytrovych - 100 famous Ukrainians]. Dictionary entry on Leontovych from "100 famous Ukrainians", www.rozum.org.ua. Retrieved 2 August 2011. (in Ukrainian)

- Леонтович Микола Дмитрович (1877–1921) композитор, хоровий диригент, громадський діяч, педагог Article analyzing the music of Mykola Leontovych (in Ukrainian)

- Ukrainian Republican Kapelle Encyclopedia of Ukraine article by Wasyl Wytwycky

- Kyrylo stetsenko – His Life Archived 7 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine Article by Wasyl Sydorenko on Musica Leopolis

- "CDs/Cassettes". www.koshetz.org. CD's and cassettes sold the O. Koshetz Choir website including a CD entitled "Mykola Leontovych – Liturgical Music"

External links

- Free scores by Mykola Leontovych in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Works by or about Mykola Leontovych at Internet Archive

- Works by Mykola Leontovych at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Leontovych Mykola, Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- Museum-Apartment of M.D.Leontovych in Tulchyn