History of the Kurds

The Kurds (Kurdish: کورد, Kurd), also the Kurdish people, (Kurdish: گەلی کورد, Gelê Kurd), are an Iranian[1][2][3] ethnic group in the Middle East. They have historically inhabited the mountainous areas to the south of Lake Van and Lake Urmia, a geographical area collectively referred to as Kurdistan. Most Kurds speak Northern Kurdish Kurmanji Kurdish (Kurmanji) and Central Kurdish (Sorani).

|

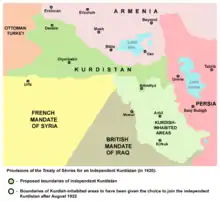

There are various hypotheses as to predecessor populations of the Kurds, such as the Carduchoi of Classical Antiquity. The earliest known Kurdish dynasties under Islamic rule (10th to 12th centuries) are the Hasanwayhids, the Marwanids, the Rawadids, the Shaddadids, followed by the Ayyubid dynasty founded by Saladin. The Battle of Chaldiran of 1514 is an important turning point in Kurdish history, marking the alliance of Kurds with the Ottomans. The Sharafnameh of 1597 is the first account of Kurdish history. Kurdish history in the 20th century is marked by a rising sense of Kurdish nationhood focused on the goal of an independent Kurdistan as scheduled by the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920. Partial autonomy was reached by Kurdistan Uyezd (1923–1926) and by Iraqi Kurdistan (since 1991), while notably in Turkish Kurdistan, an armed conflict between the Kurdish insurgent groups and Turkish Armed Forces was ongoing from 1984 to 1999, and the region continues to be unstable with renewed violence flaring up in the 2000s.

Name

There are different theories about the origin of the name Kurd. According to one theory, it originates in Middle Persian as كورت kwrt-, a term for "nomad; tent-dweller".[Note 1] After the Muslim conquest of Persia, this term was adopted into Arabic as kurd-, and was used specifically for nomadic tribes.[Note 2]

The ethnonym Kurd may ultimately derive from an ancient toponym in the upper Tigris basin. According to the English Orientalist Godfrey Rolles Driver, the term Kurd is related to the Sumerian Karda which was found in Sumerian clay tablets of the third millennium B.C. He wrote in a paper published in 1923 that the term Kurd was not used differently by different nations and by examining the philological variations of Karda in different languages, such as Cordueni, Gordyeni, Kordyoui, Karduchi, Kardueni, Qardu, Kardaye, Qardawaye, he finds that the similarities undoubtedly refer to a common descent.[7]

As for the Middle Persian noun kwrt- originating in an ancient toponym, it has been argued that it may ultimately reflect a Bronze Age toponym Qardu, Kar-da,[8] which may also be reflected in the Arabic (Quranic) toponym Ǧūdī (re-adopted in Kurdish as Cûdî) [9][10] The name would be continued in classical antiquity as the first element in the toponym Corduene, and its inhabitants, mentioned by Xenophon as the tribe of the Carduchoi who opposed the retreat of the Ten Thousand through the mountains north of Mesopotamia in the 4th century BC. This view is supported by some recent academic sources which have considered Corduene as proto-Kurdish region.[11] However, some modern scholars reject these connections.[12][13] Alternatively, kwrt- may be a derivation from the name of the Cyrtii tribe instead.[Note 3]

According to some sources, by the 16th century, there seems to develop an ethnic identity designated by the term Kurd among various Northwestern Iranian groups,[Note 4][Note 5][Note 6][Note 7] without reference to any specific Iranian language.[6][Note 6]

Kurdish scholar Mehrdad Izady argues that any nomadic groups called kurd in medieval Arabic are "bona fide ethnic Kurds", and that it is conversely the non-Kurdish groups descended from them who have "acquired separate ethnic identities since the end of the medieval period".[Note 8]

Sherefxan Bidlisi in the 16th century states that there are four divisions of "Kurds": Kurmanj, Lur, Kalhor and Guran, each of which speak a different dialect or language variation. Paul (2008) notes that the 16th-century usage of the term Kurd as recorded by Bidlisi, regardless of linguistic grouping, might still reflect an incipient Northwestern Iranian "Kurdish" ethnic identity uniting the Kurmanj, Kalhor, and Guran.[Note 9]

Early history

Kurdish is a language of the Northwestern Iranian group which has likely separated from the other dialects of Central Iran during the early centuries AD (the Middle Iranian period). Kurdish has in turn emerged as a group within Northwest Iranian during the Medieval Period (roughly 10th to 16th centuries).[15]

The Kurdish people are believed to be of heterogeneous origins, both from Iranian-speaking and non-Iranian peoples.[20][Note 10] combining a number of earlier tribal or ethnic groups[Note 11] including Lullubi,[23] Guti,[24][25][23] Cyrtians,[26] Carduchi.[27][28][Note 12]

The present state of knowledge about Kurdish allows, at least roughly, drawing the approximate borders of the areas where the main ethnic core of the speakers of the contemporary Kurdish dialects was formed. The most argued hypothesis on the localisation of the ethnic territory of the Kurds remains D.N. Mackenzie's theory, proposed in the early 1960s.[30] Developing the ideas of P. Tedesco[31] and regarding the common phonetic isoglosses shared by Kurdish, Persian, and Baluchi, D.N. Mackenzie concluded that the speakers of these three languages form a unity within Northwestern Iranian. He has tried to reconstruct such a Persian-Kurdish-Baluchi linguistic unity presumably in the central parts of Iran. According to his theory, the Persians (or Proto-Persians) occupied the province of Fars in the southwest (proceeding from the fact that the Achaemenids spoke Persian), the Balochs (Proto-Balochs) inhabited the central areas of Western Iran, and the Kurds (Proto-Kurds), in the wording of G. Windfuhr (1975: 459), lived either in northwestern Luristan or in the province of Isfahan.[32]

Early Kurdish principalities

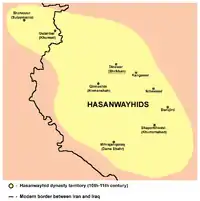

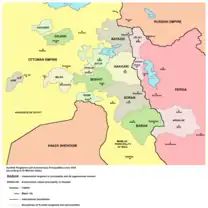

In the second half of the 10th century there were five Kurdish principalities: in the north the Shaddadid (951–1174) (in parts of Armenia and Arran) and Rawadid (955–1221) in Tabriz and Maragheh, in the East the Hasanwayhids (959–1015), the Annazid (990–1117) (in Kermanshah, Dinawar and Khanaqin) and in the West the Marwanid (990–1096) of Diyarbakır.

Later in the 12th century, the Kurdish[33] Hazaraspid dynasty established its rule in southern Zagros and Luristan and conquered territories of Kuhgiluya, Khuzestan and Golpayegan in the 13th century and annexed Shushtar, Hoveizeh and Basra in the 14th century.

One of these dynasties may have been able, during the decades, to impose its supremacy on the others and build a state incorporating the whole Kurdish country if the course of history had not been disrupted by the massive invasions of tribes surging out of the steppes of Central Asia. Having conquered Iran and imposed their yoke on the caliph of Baghdad, the Seljuq Turks annexed the Kurdish principalities one by one. Around 1150, Ahmad Sanjar, the last of the great Seljuq monarchs, created a province out of these lands and called it Kurdistan. The province of Kurdistan, formed by Sanjar, had as its capital the village Bahar (which means lake or sea), near ancient Ecbatana (Hamadan). It included the vilayets of Sinjar and Shahrazur to the west of the Zagros mountain range and those of Hamadan, Dinawar and Kermanshah to the east of this range. An autochthonous civilization developed around the town of Dinawar (today ruined), located 75 km North-East of Kermanshah, whose radiance was later only partially replaced by that of Senna, 90 km further North.[34]

Marco Polo (1254–1324) met Kurds in Mosul on his way to China, and he wrote what he had learned about Kurdistan and the Kurds to enlighten his European contemporaries. The Italian Kurdologist Mirella Galetti, sorted these writings which were translated into Kurdish.[35]

Ayyubid period

One of the periods where Kurds were at the peak of their power was during the 12th century, when Saladin, who belonged to the Rawadiya branch of the Hadabani tribe, founded the Ayyubid dynasty, under which several Kurdish chieftainships were established. The dynasty ruled areas extending from the Kurdish regions to as far as Egypt and Yemen.[36][37]

Kurdish principalities after the Mongol period

After the Mongol period, Kurds established several independent states or principalities such as Ardalan, Badinan, Baban, Soran, Hakkari and Badlis. A comprehensive history of these states and their relationship with their neighbors is given in the famous textbook of Sharafnama written by Prince Sharaf al-Din Biltisi in 1597. The most prominent among these was Ardalan which was established in the early 14th century. The state of Ardalan controlled the territories of Zardiawa (Karadagh), Khanaqin, Kirkuk, Kifri, and Hawraman, despite being vassals themselves of the various in Persia centred succeeding Turkic federations in the region, namely that of the Kara Koyunlu, and the Ak Koyunlu specifically. The capital city of this state of Ardalan was first in Sharazour in Iraqi Kurdistan, but was moved to Sinne (in Iran) later on. The Ardalan Dynasty was allowed to rule the region as vassals by many of the sovereign rulers over the wider territory, until the Qajar monarch Nasser-al-Din Shah (1848–1896) ended their rule in 1867.

Kurdish quarters

In the Middle Ages, in many cities outside of Kurdistan, Kurdish quarters were formed as a result of an influx of Kurdish tribal forces, as well as scholars.[38] In these cities, Kurds often also had mosques, madrasahs and other edifices.

- In Aleppo, the Haret al-Akrad. The city of Aleppo also had Kurdish mosques like al-Zarzari, al-Mihrani, al-Bashnawayin.[39]

- In Baghdad, Darb al-Kurd, recorded since the 11th century.[40]

- In Barda, Bab al-Akrad,[41] recorded in the 10th century.

- In Cairo, Haret al-Akrad, at al-Maqs.[42]

- In Damascus, Mount Qasyun at Rukn al-dîn and Suq al-Saruja.[43] Kurdish notables had also built mosques and madrasahs by name of al-Mudjadiyya, Sab‘ al-Madjânîn, al-Mihrani. Some other notables who patronized buildings were Balâchû al-Kurdî, Musa al-Kurdi, Habib al-Kurdi. There also was a Kurdish cemetery.[39]

- In Gaza, Shuja'iyya,[44][45] named after Shuja' al-Din Uthman al-Kurdi, who died in 1239.

- In Hebron, Haret al-Akrad: associated with the Ayyubid conquests.

- In Jerusalem, Haret al-Akrad (later Haret esh-Sharaf,[46][47] named after a certain Sharaf ad-Din Musa, who died in 1369).[48] The city also had a madrasah-ribat by the name of Ribat al-Kurd, built in 1294 by Amir Kurd al-Mansuri (Kurt al-Manṣūrī).[49]

Safavid period

For many centuries, starting in the early modern period with Ismail I, Shah of Safavid Persia, and Ottoman Sultan Selim I, the Kurds came under the suzerainty of the two most powerful empires of the Near East and staunch arch rivals, the Sunni Ottoman Empire and the various Shia Empires. It started off with the rule of Ismail I, who ruled over all regions that encompass native Kurdish living areas, and far beyond. During the years 1506–1510, Yazidis revolted against Ismail I (who may have had Kurdish ancestry himself).[50][51][52][53][Note 13][56][Note 14][Note 15][Note 16][Note 17][Note 18][Note 19] Their leader, Shir Sarim, was defeated and captured in a bloody battle wherein several important officers of Ismail lost their lives. The Kurdish prisoners were put to death "with torments worse than which there may not be".[63]

In the mid-17th century the Kurds on the western borders disposed of firearms, According to Tavernier, the mountain people between Nineveh and Isfahan would not sell anything but for gunpowder and bullets. Even so, firearms were incorporated neither wholesale nor wholeheartedly among the Kurds, apparently for the same reasons that hindered their acceptance in iran proper. In a Persian statistical overview of tribes dating from the period of Shah sultan Husayn in the early 18th century, it is said that the Kurds of Zafaranlo tribe refused to carry the Tufang, because they considered it unmanly to do so, as a result of which most continued to fight with lance and sword, and some with arrow and bow.[64]

Displacement of the Kurds

Removal of the population from along their borders with the Ottomans in Kurdistan and the Caucasus was of strategic importance to the Safavids. Hundreds of thousands of Kurds were moved to other regions in the Safavid empire, only to defend the borders there. Hundreds of thousands of other ethnic groups living in the Safavid empire such as the Armenians, Assyrians, Georgians, Circassians, and Turkomans, were also removed from the border regions and resettled in the interior of Persia, but mainly for other reasons such as socio-economic, and bureaucratic ones. During several periods, as the borders moved progressively eastward, with the Ottomans pushing deeper into the Persian domains, entire Kurdish regions of Anatolia were at one point or another exposed to horrific acts of despoliation and deportation. These began under the reign of the Safavid Shah Tahmasp I (ruled 1524–1576). Between 1534 and 1535, Tahmasp, using a policy of scorched earth against his Ottoman arch rivals, began the systematic destruction of the old Kurdish cities and the countryside. When retreating before the Ottoman army, Tahmasp ordered the destruction of crops and settlements of all sizes, driving the inhabitants before him into Azerbaijan, from where they were later transferred permanently, nearly 1,600 km (1,000 miles) east, into Khurasan.

Shah Abbas inherited a state threatened by the Ottomans in the west and the Uzbeks in the northeast. He bought off the former, in order to gain time to defeat the latter, after which he selectively depopulated the Zagros and Caucasus approaches, deporting Kurds, Armenians, Georgians, North Caucasians and others who might, willingly or not, supply, support or be any use in an Ottoman campaign in the region. Shah Abbas forcibly depopulated much of the Kurdish lands ahead of the Ottoman expansion. He made it lucrative and prestigious for Kurds to become military conscripts, and raised an army of tens of thousands of predominantly Kurdish soldiers. Abbas also razed villages to the ground and marched the people into the Persian heartland.[65]

The magnitude of Safavid Scorched earth policy can be glimpsed through the works of the Safavid court historians. One of these, Iskandar Bayg Munshi, describing just one episode, writes in the Alam-ara ye Abbasi that Shah Abbas, in furthering the scorched earth policy of his predecessors, set upon the country north of the Araxes and west of Urmia, and between Kars and Lake Van, which he commanded to be laid waste and the population of the countryside and the entire towns rounded up and led out of harm's way. Resistance was met "with massacres and mutilation; all immovable property, houses, churches, mosques, crops ... were destroyed, and the whole horde of prisoners was hurried southeast before the Ottomans should counterattack". Many of these Kurds ended up in Khurasan, but many others were scattered into the Alburz mountains, central Persia, and even Balochistan. They became the nucleus of several modern Kurdish enclaves outside Kurdistan proper, in Iran and Turkmenistan. On one occasion Abbas I is said to have intended to transplant 40,000 Kurds to northern Khorasan but to have succeeded in deporting only 15,000 before his troops were defeated.[66][67] While the deported Kurds became the nucleus of the modern central Anatolian Kurdish enclave, the Turkmen tribes in Kurdistan eventually assimilated.[68]

Massacre of Ganja

According to the early 17th century Armenian historian Arak'el Davrizhetsi, the Sunni Kurdish tribe of Jekirlu inhabited the region of Ganja. In 1606, when Shah Abbas reconquered Ganja, he ordered a general massacre of the Jekirlu. Even infants were slaughtered with sharp swords.[69]

Battle of Dimdim

There is a well documented historical account of a long battle in 1609–1610 between Kurds and the Safavid Empire. The battle took place around a fortress called "Dimdim" (DimDim) in Beradost region around Lake Urmia in northwestern Iran. In 1609, the ruined structure was rebuilt by "Emîr Xan Lepzêrîn" (Golden Hand Khan), ruler of Beradost, who sought to maintain the independence of his expanding principality in the face of both Ottoman and Safavid penetration into the region. Rebuilding Dimdim was considered a move toward independence that could threaten Safavid power in the northwest. Many Kurds, including the rulers of Mukriyan rallied around Amir Khan. After a long and bloody siege led by the Safavid grand vizier Hatem Beg, which lasted from November 1609 to the summer of 1610, Dimdim was captured. All the defenders were massacred. Shah Abbas ordered a general massacre in Beradost and Mukriyan (reported by Eskandar Beg Turkoman, Safavid Historian in the Book Alam Aray-e Abbasi) and resettled the Turkish Afshar tribe in the region while deporting many Kurdish tribes to Khorasan. Although Persian historians (like Eskandar Beg) depicted the first battle of Dimdim as a result of Kurdish mutiny or treason, in Kurdish oral traditions (Beytî dimdim), literary works (Dzhalilov, pp. 67–72), and histories, it was treated as a struggle of the Kurdish people against foreign domination. In fact, Beytî dimdim is considered a national epic second only to Mem û Zîn by Ahmad Khani. The first literary account of this battle is written by Faqi Tayran.[70][71][72]

Ottoman period

.jpg.webp)

When Sultan Selim I, after defeating Shah Ismail I in 1514, annexed Western Armenia and Kurdistan, he entrusted the organisation of the conquered territories to Idris, the historian, who was a Kurd of Bitlis. He divided the territory into sanjaks or districts, and, making no attempt to interfere with the principle of heredity, installed the local chiefs as governors. He also resettled the rich pastoral country between Erzerum and Yerevan, which had lain in waste since the passage of Timur, with Kurds from the Hakkari and Bohtan districts.

Janpulat Revolt

The Janpulat (Turkish: Canpulatoğlu, Arabic: Junblat[73]) clan was ruled by local Kurdish feudal lords in the Jabal al-Akrad and Aleppo region for almost a century before the Ottoman conquest of Syria. Their leader, Hussein Janpulatoğlu, was appointed as governor of Aleppo in 1604, however he was executed by Çiğalzade Sinan Pasha allegedly for his late arrival at the Battle of Urmia. According to Abul Wafa Al-Urdi, Janpulat had been murdered because of his Kurdish origins. His nephew, Ali Janbulad, revolted in revenge and declared sovereignty in 1606 and was supported by the Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinand I.[74] He conquered a region stretching from Hama to Adana with 30,000 troops.[75] Grand Vizier, Murad Pasha, marched against him with a large army in 1607. Ali Pasha managed to escape and was later pardoned and appointed governor of province of Temesvár in Hungary. He was eventually executed by Murad Pasha in Belgrade in 1610.[76]

Rozhiki Revolt

In 1655, Abdal Khan the Kurdish Rozhiki ruler of Bidlis, formed a private army and fought a full scale war against the Ottoman troops. Evliya Çelebi noted the presence of many Yazidis in his army.[77] The main reason for this armed insurrection was the discord between Abdal Khan and Melek Ahmad Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Diyarbakır and Abdal Khan. The Ottoman troops marched onto Bidlis and committed atrocities against civilians as they passed through Rozhiki territory. Abdal Khan had built great stone redoubts around Bitlis, and also old city walls were defended by a large army of Kurdish infantry armed with muskets. Ottomans attacked the outer defensive perimeter and defeated Rozhiki soldiers, then they rushed to loot Bidlis and attacked the civilians. Once the Ottoman force established its camp in Bidlis, in an act of revenge, Abdal Khan made a failed attempt to assassinate Melek Ahmad Pasha. A unit of twenty Kurdish soldiers rode into the tent of Yusuf Kethuda, the second-in-command and fought a ferocious battle with his guards. After the fall of Bidlis, 1,400 Kurds continued to resist from the city's old citadel. While most of these surrendered and were given amnesty, 300 of them were massacred by Melek Ahmad with 70 of them dismembered by sword and cut into pieces.[78]

Bedr Khan of Botan

Except for the short Iranian recapture under Nader Shah in the first half of the 18th century, the system of administration introduced by Idris remained unchanged until the close of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29. But the Kurds, owing to the remoteness of their country from the capital and the decline of Turkey, had greatly increased in influence and power, and had spread westwards over the country as far as Ankara.

After the war with Russia, the Kurds attempted to free themselves from Ottoman control which resulted in the Bedr Khan clan uprising in 1834. The Ottoman Porte made the decision to then end the autonomous regions of the Eastern portion of the Empire. This was done by Rashid Pasha, also a Kurd.[79] The principal towns were strongly garrisoned, and many of the Kurd beys were replaced by Turkish governors. A rising under Bedr Khan Bey in 1843 was firmly repressed, and after the Crimean War the Turks strengthened their hold on the country. In the 1830's, Bedr Khan was defeated by the united Assyrians of Hakkari.[80]

The modernizing and centralizing efforts of Sultan Mahmud II antagonized Kurdish feudal chiefs. As a result two powerful Kurdish families rebelled against the Ottomans in 1830. Bedr Khan of Botan rose up in the west of Kurdistan, around Diyarbakır, and Muhammad Pasha of Rawanduz rebelled in the east and established his authority in Mosul and Erbil. At this time, Turkish troops were preoccupied with invading Egyptian troops in Syria and were unable to suppress the revolt. As a result, Bedr Khan extended his authority to Diyarbakır, Siverik (Siverek), Veransher (Viranşehir), Sairt (Siirt), Sulaimania (Sulaymaniyah) and Sauj Bulaq (Mahabad). He established a Kurdish principality in these regions until 1845. He struck his own coins, and his name was included in Friday sermons. In 1847, the Turkish forces turned their attention toward this area, and defeated Bedr Khan and exiled him to Crete. He was later allowed to return to Damascus, where he lived until his death in 1868. Bedr Khan Beg made two campaigns in 1843 and 1846 against the Assyrian Christians (Nestorians) of Hakkari and massacred up to 4,000 Assyrians in an attempt to Islamize the region; those Assyrians who met their fate were the mother and the two brothers of the yet to be spiritual Assyrian leader Mar Shimun.[81]

Bedr Khan became king when his brother died. His brother's son became very upset over this, which the Turks exploited in tricking him into fighting his uncle. They told him that they would make him king if he killed Bedr Khan. Bedr Khan's nephew brought many Kurdish warriors with to attack his uncle's forces. After defeating Bedr Khan, Bedr Khan's nephew was executed instead of becoming king as the Turks had promised.[79] There are two famous Kurdish songs about this battle, called "Ezdin Shêr" and "Ez Xelef im". After this, there were further revolts in 1850 and 1852.[82]

Kurdistan as an administrative entity had a brief and shaky existence of 17 years between 13 December 1847 (following Bedirhan Bey's revolt) and 1864, under the initiative of Koca Mustafa Reşit Pasha during the Tanzimat period (1839–1876) of the Ottoman Empire. The capital of the province was, at first, Ahlat, and covered Diyarbekir, Muş, Van, Hakkari, Botan (Cizre) and Mardin. In the following years, the capital was transferred several times, first from Ahlat to Van, then to Muş and finally to Diyarbakır. Its area was reduced in 1856 and the province of Kurdistan within the Ottoman Empire was abolished in 1864. Instead, the former provinces of Diyarbekir and Van have been re-constituted.[83] Around 1880, Shaikh Ubaidullah led a revolt aiming at bringing the areas between Lakes Van and Urmia under his own rule, however Ottoman and Qajar forces succeeded in defeating the revolt.[84]

Shaikh Ubaidullah's Revolt and Armenians

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 was followed by the uprising of Sheikh Ubeydullah in 1880–1881 to found an independent Kurd principality under the protection of Turkey. The attempt, at first encouraged by the Porte, as a reply to the projected creation of an Armenian state under the suzerainty of Russia, collapsed after Ubeydullah's raid into Persia, when various circumstances led the central government to reassert its supreme authority. Until the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829 there had been little hostile feeling between the Kurds and the Armenians, and as late as 1877–1878 the mountaineers of both races had co-existed fairly well together.

In 1891, the activity of the Armenian Committees induced the Porte to strengthen the position of the Kurds by raising a body of Kurdish irregular cavalry, who were well-armed Hamidieh soldiers after the Sultan Abd-ul-Hamid II. Minor disturbances constantly occurred, and were soon followed by a massacre and rape of Armenians at Sasun by Kurdish nomads and Ottoman troops.[85]

20th century history

Rise of nationalism

Kurdish nationalism emerged at the end of the 19th Century around the same time as Turks and Arabs began to embrace an ethnic sense of identity in place of earlier forms of solidarity such as the idea of Ottoman citizenship or membership of a religious community, or millet.[86] Revolts occurred sporadically but only in 1880 with the uprising led by Sheikh Ubeydullah were demands as an ethnic group or nation made. Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid responded by a campaign of integration by co-opting prominent Kurdish opponents to strong Ottoman power with prestigious positions in his government. This strategy appears successful given the loyalty displayed by the Kurdish Hamidiye regiments during World War I.[87]

The Kurdish ethnonationalist movement that emerged following World War I and end of the Ottoman empire was largely reactionary to the changes taking place in mainstream Turkey, primarily radical secularization which the strongly Muslim Kurds abhorred, centralization of authority which threatened the power of local chieftains and Kurdish autonomy, and rampant Turkish nationalism in the new Turkish Republic which obviously threatened to marginalize them.[88]

Western powers (particularly the United Kingdom) fighting the Turks also promised the Kurds they would act as guarantors for Kurdish independence, a promise they subsequently broke. One particular organization, the Kurdish Teali Cemiyet (Society for the Rise of Kurdistan, or SAK) was central to the forging of a distinct Kurdish identity. It took advantage of period of political liberalization during the Second Constitutional Era (1908–1920) of Turkey to transform a renewed interest in Kurdish culture and language into a political nationalist movement based on ethnicity.[88]

After World War I

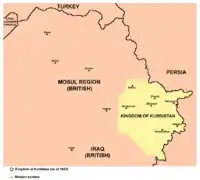

Some Kurdish groups sought self-determination and the championing in the Treaty of Sèvres of Kurdish autonomy in the aftermath of World War I, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk prevented such a result. Kurds backed by the United Kingdom declared independence in 1927 and established so-called Republic of Ararat. Turkey suppressed Kurdist revolts in 1925, 1930, and 1937–1938, while Iran did the same in the 1920s to Simko Shikak at Lake Urmia and Jaafar Sultan of Hewraman region who controlled the region between Marivan and north of Halabja.

From 1922 to 1924 in Iraq, a Kingdom of Kurdistan existed. When Ba'athist administrators thwarted Kurdish nationalist ambitions in Iraq, war broke out in the 1960s. In 1970 the Kurds rejected limited territorial self-rule within Iraq, demanding larger areas including the oil-rich Kirkuk region. For recent developments see Iraqi Kurdistan.

In 1922, an investigation was initiated for Nihad Pasha, the commander of El-Cezire front, by Adliye Encümeni (Council of Justice) of Grand National Assembly of Turkey with allegations of fraud. During a confidential convention on the issue on 22 July, a letter of introductions by the Cabinet of Ministers and signed by Mustafa Kemal was read. The text was referring to the region as "Kurdistan" three times and providing Nihad Pasha with full authorities to support the local Kurdish administrations (idare-i mahallîyeye dair teşkilâtlar) as per the principle of self-determination (Milletlerin kendi mukadderatlarını bizzat idare etme hakkı), in order to gradually establish a local government in the regions inhabited by Kurds (Kürtlerle meskûn menatık).[89]

In 1931, Iraqi Kurdish statesman Mihemed Emîn Zekî, while serving as the Minister of the Economy in the first Nuri as-Said government, drew the boundaries of Turkish Kurdistan as: "With mountains of Ararat and the Georgian border (including the region of Kars, where Kurds and Georgians live side by side) to the north, Iranian border to the east, Iraqi border to the south, and to the west, a line drawn from the west of Sivas to İskenderun. These boundaries are also in accord with those drawn by the Ottomans."[90] In 1932, Garo Sassouni, formerly a prominent figure of Dashnak Armenia, defined the borders of "Kurdistan proper" (excluding whole territory of Wilsonian Armenia) as: "... with a line from the south of Erzincan to Kharput, incorporating Dersim, Çarsancak, and Malatya, including the mountains of Cebel-i Bereket and reaching the Syrian border", also adding, "these are the broadest boundaries of Kurdistan that can be claimed by Kurds."[91]

During the 1920s and 1930s, several large-scale Kurdish revolts took place in this region. The most important ones were the Saikh Said Rebellion in 1925, the Ararat Revolt in 1930 and the Dersim Revolt in 1938 (see Kurds in Turkey). Following these rebellions, the area of Turkish Kurdistan was put under martial law and many Kurds were displaced. Government also encouraged resettlement of Albanians from Kosovo and Assyrians in the region to change the population makeup. These events and measures led to a long-lasting mutual distrust between Ankara and the Kurds.[92]

In 1937, during the period of Stalinism, many Kurds in Armenia, along with Kurds in Azerbaijan, became victims of forced migration, and were forcibly deported to Kazakhstan.[93][94]

World War II

During World War Two, the Kurds formed 10 companies in the Iraq Levies that the British had recruited in Iraq. Kurds supported the British in the defeating the pro-Nazi 1941 Iraqi coup d'état.[95] Twenty-five percent of the Iraq Levies' 1st Parachute Company was Kurdish. The Parachute Company was attached to the Royal Marine Commando and was active in Albania, Italy, Greece, and Cyprus.[96][97]

Kurds participated in the Soviet occupation of northern Iraq in 1941,[98] creating the Persian Corridor, a vital supply line for the USSR. This led to the short-lived formation of the Kurdish Republic of Mahabad.

Despite the fact they were a tiny minority in the Soviet Union, Kurds played a significant role in the Soviet war effort. On 1 October 1941, Samand Siabandov was awarded the honour Hero of the Soviet Union. Kurds served at Smolensk, Sevastopol, Leningrad, and Stalingrad. Kurds took part in the partisan movement behind German lines. Karaseva received both the Hero of the Soviet Union medal and the medal Partisan of the Fatherland War (First Degree) for organising partisans to fight against the Germans in Volhynia Oblast in Ukraine. Kurds took part in the advance into Hungary and the invasion of Japanese-held Manchuria.[98][99]

Post-WWII

Turkey

.jpg.webp)

About half of all Kurds live in Turkey. According to the CIA Factbook they account for 18 percent of the Turkish population.[100] They are predominantly distributed in the southeastern corner of the country.[101]

The best available estimate of the number of persons in Turkey speaking the Kurdish language is about five million (1980). About 3,950,000 others speak Northern Kurdish (Kurmanji) (1980).[102] While population increase suggests that the number of speakers has grown, it is also true that the ban on the use of the language in Turkey was only lifted in 1991 and still exists in most official settings (including schools), and that many fewer ethnic Kurds live in the countryside where the language has traditionally been used. The number of speakers is clearly less than the 15 million or so persons who identify themselves as ethnic Kurds.

From 1915 to 1918, Kurds struggled to end Ottoman rule over their region. They were encouraged by Woodrow Wilson's support for non-Turkish nationalities of the empire and submitted their claim for independence to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.[103] The Treaty of Sèvres stipulated the creation of an autonomous Kurdish state in 1920, but the subsequent Treaty of Lausanne (1923) failed to mention Kurds. After the Sheikh Said rebellion was suppressed in 1925, Kemal Atatürk established a Reform Council for the East (Turkish: Şark İslahat Encümeni)[104] which prepared the Report for Reform in the East (Turkish: Şark İslahat Raporu) which encouraged the creation of Inspectorates-Generals (Turkish: Umumi Müfettişlikler, UMs), in the areas comprising a majority Kurdish population.[105] Following there were established three regional Inspectorates Generals comprising the Kurdish provinces, the Inspectorates General were ruled with Martial Law and Kurdish notables in the areas were meant to be resettled to the west of Turkey. The Inspectorates Generals were disestablished in 1952.[106]

During the relatively open government of the 1950s, Kurds gained political office and started working within the framework of the Turkish Republic to further their interests but this move towards integration was halted with the 1960 Turkish coup d'état.[87] The 1970s saw an evolution in Kurdish nationalism as Marxist political thought influenced a new generation of Kurdish nationalists opposed to the local feudal authorities who had been a traditional source of opposition to authority, eventually they would form the militant separatist PKK, or Kurdistan Workers Party in English.

Following these events, Turkey officially denied the existence of the Kurds or an other distinct ethnic groups and any expression by the Kurds of their ethnic identity was harshly repressed. Until 1991, the use of the Kurdish language – although widespread – was illegal. As a result of reforms inspired by the EU, music, radio and television broadcasts in Kurdish are now allowed albeit with severe time restrictions (for example, radio broadcasts can be no longer than sixty minutes per day nor can they constitute more than five hours per week while television broadcasts are subject to even greater restrictions). Additionally, education in Kurdish is now permitted though only in private institutions.

As late as 1994, however, Leyla Zana, the first female Kurdish representative in Grand National Assembly of Turkey, was charged with making "separatist speeches" and sentenced to 15 years in prison. At her inauguration as an MP, she reportedly identified herself as a Kurd. Amnesty International reported that "[s]he took the oath of loyalty in Turkish, as required by law, then added in Kurdish, 'I shall struggle so that the Kurdish and Turkish peoples may live together in a democratic framework.' In response to this, calls for her arrest blaming her of being a "Separatist" and "Terrorist" were heard in the Turkish parliament.[107]

The Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan (PKK), also known as KADEK and Kongra-Gel is Kurdish militant organization which has waged an armed struggle against the Turkish state for cultural and political rights and self-determination for the Kurds. Turkey's military allies the US, the EU, and NATO see the PKK as a terrorist organization.

From 1984 to 1999, the PKK and the Turkish military engaged in open war, and much of the countryside in the southeast was depopulated, with Kurdish civilians moving to local defensible centers such as Diyarbakır, Van, and Şırnak, as well as to the cities of western Turkey and even to western Europe. The causes of the depopulation included PKK atrocities against Kurdish clans who they could not control, the poverty of the southeast, and the Turkish state's military operations.[108] Human Rights Watch has documented many instances where the Turkish military forcibly destroyed houses and villages. An estimated 3,000 Kurdish villages in Turkey were virtually wiped off the map, representing the displacement of more than 378,000 people.[109][110][111][112]

Nelson Mandela refused to accept the Atatürk Peace Award in 1992 because of the oppression of the Kurds,[113] but later accepted the award in 1999.[114]

Iraq

Kurds make up around 17% of Iraq's population. They are the majority in at least three provinces in Northern Iraq which are known as Iraqi Kurdistan. There are around 300,000 Kurds living in the Iraqi capital Baghdad, 50,000 in the city of Mosul and around 100,000 Kurds living elsewhere in Southern Iraq.[115] Kurds led by Mustafa Barzani were engaged in heavy fighting against successive Iraqi regimes from 1960 to 1975. In March 1970, Iraq announced a peace plan providing for Kurdish autonomy. The plan was to be implemented in four years.[116] However, at the same time, the Iraqi regime started an Arabization program in the oil rich regions of Kirkuk and Khanaqin.[117] The peace agreement did not last long, and in 1974, the Iraqi government began a new offensive against the Kurds. Moreover, in March 1975, Iraq and Iran signed the Algiers Accord, according to which Iran cut supplies to Iraqi Kurds. Iraq started another wave of Arabization by moving Arabs to the oil fields in northern Iraq, particularly those around Kirkuk.[118] Between 1975 and 1978, 200,000 Kurds were deported to other parts of Iraq.[119]

During the Iran–Iraq War in the 1980s, the regime implemented anti-Kurdish policies and a de facto civil war broke out. Iraq was widely condemned by the international community, but was never seriously punished for oppressive measures such as the mass murder of hundreds of thousands of civilians, the wholesale destruction of thousands of villages and the deportation of thousands of Kurds to southern and central Iraq. The campaign of Iraqi government against Kurds in 1988 was called Anfal ("Spoils of War"). The Anfal attacks led to destruction of two thousand villages and death of between 50 and 100,000 Kurds.[120]

After the Kurdish uprising in 1991 (Kurdish: Raperîn) led by the PUK and KDP, Iraqi troops recaptured the Kurdish areas and hundreds of thousand of Kurds fled to the borders. To alleviate the situation, a "safe haven" was established by the Security Council. The autonomous Kurdish area was mainly controlled by the rival parties KDP and PUK. The Kurdish population welcomed the American troops in 2003 by holding celebrations and dancing in the streets.[121][122][123][124] The area controlled by peshmerga was expanded, and Kurds now have effective control in Kirkuk and parts of Mosul. By the beginning of 2006, the two Kurdish areas were merged into one unified region. A series of referendums were scheduled to be held in 2007, to determine the final borders of the Kurdish region.

In early June 2010, following a visit to Turkey by one of the PKK leaders, the PKK announced an end to the cease fire,[125] followed by an air attack on several border villages and rebel positions by the Turkish air force.[Note 20]

On 11 July 2014 KRG forces seized control of the Bai Hassan and Kirkuk oilfields, prompting a condemnation from Baghdad and a threat of "dire consequences", if the oilfields were not relinquished back to Iraq's control.[127] The 2017 Kurdistan Region independence referendum took place on September 25, with 92.73% voting in favor of independence. This triggered a military operation in which the Iraqi government retook control of Kirkuk and surrounding areas, and forced the KRG to annul the referendum.

Iran

The Kurdish region of Iran has been a part of the country since ancient times. Nearly all of Kurdistan was part of the Iranian Empire until its western part was lost during the wars against the Ottoman Empire.[128] Following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, at the Paris Conferences in 1919, Tehran demanded various territories including Turkish Kurdistan, Mosul, and even Diyarbakır, but these demands were quickly rejected by Western powers.[129] Instead, the Kurdish area was divided by modern Turkey, Syria and Iraq.[130] Today, the Kurds inhabit mostly North-Western Iran but also parts of Khorasan, and constitute approximately 7–10%[131] of Iran's overall population (6.5–7.9 million), compared to 10.6% (2 million) in 1956 or 8% (800,000) in 1850.[132]

Unlike in other Kurdish-populated countries, there are very strong ethno-linguistical, historical and cultural ties between Kurds and others as Iranian peoples.[131] Some of modern Iranian dynasties like Safavids and Zands are considered to be partly of Kurdish origin. Kurdish literature in all of its forms (Kurmanji, Sorani and Gorani) has been developed within historical Iranian boundaries under strong influence of Persian language.[130] Due to Kurds sharing a common history, very close cultural and linguistic links as well as common origins with the rest of Iran, this is seen as a reason why Kurdish leaders in Iran do not want a separate Kurdish state.[131][133][134]

The government of Iran has always been implacably opposed to any sign of independence for the Iranian Kurds.[131] During and shortly after the First World War, the government of Iran was ineffective and had very little control over events in the country and several Kurdish tribal chiefs gained local political power, and established large confederations.[133] In the same time, a wave of nationalism from the disintegrating Ottoman Empire has partly influenced some Kurdish chiefs in border region, and they posed as Kurdish nationalist leaders.[133] Prior to this, identity in both countries largely relied upon religion i.e. Shia Islam in the particular case of Iran.[134][135] In 19th century Iran, Shia–Sunni animosity and describing Sunni Kurds as Ottoman fifth column was quite frequent.[136]

During the late 1910s and early 1920s, tribal revolt led by Kurdish chieftain Simko Shikak swept across Iranian Kurdistan. Although elements of Kurdish nationalism were present in the movement, historians agree they were hardly articulate enough to justify a claim that recognition of Kurdish identity was a major issue in Simko's movement, and he had to rely heavily on conventional tribal motives.[133] Government forces and non-Kurds were not the only ones to have allegedly been attacked, the Kurdish population was also robbed and assaulted.[133][137] The fighters do not appear to have felt any sense of unity or solidarity with fellow Kurds.[133] Kurdish insurgency and seasonal migrations in the late 1920s, along with long-running tensions between Tehran and Ankara, resulted in border clashes and even military penetrations in both Iranian and Turkish territory.[129] Two regional powers have used Kurdish tribes as tool for own political benefits: Turkey has provided military help and refuge for anti-Iranian Turcophone Shikak rebels in 1918–1922,[138] while Iran did the same during Ararat rebellion against Turkey in 1930. The Iranian government's forced detribalization and sedentarization in the 1920s and 1930s resulted in many tribal revolts in Iranian regions such as Azerbaijan, Luristan and Kurdistan.[139] In particular case of the Kurds, these policies partly contributed to developing revolts among some tribes.[133]

As a response to growing Pan-Turkism and Pan-Arabism in region which were seen as potential threats to the territorial integrity of Iran, Pan-Iranist ideology has been developed in the early 1920s.[135] Some of such groups and journals openly advocated Iranian support to the Kurdish opposition against Turkey.[140] Pahlavi dynasty has endorsed Iranian ethnic nationalism[135] which allegedly seen the Kurds as integral part of the Iranian nation.[134] Mohammad Reza Pahlavi has supposedly praised the Kurds himself as "pure Iranians" or "one of the most noble Iranian peoples".[141] Another significant ideology during this period was Marxism which arose among Kurds under influence of the USSR. It culminated in the Iran crisis of 1946 which included a bold attempt KDP-I and communist groups to try to gain autonomy[142] to establish the Soviet puppet government[143][144][145] called Republic of Mahabad. It arose along with Azerbaijan People's Government, another Soviet puppet state.[131][146] The state itself encompassed a very small territory, including Mahabad and the adjacent cities, unable to incorporate the southern Iranian Kurdistan which fell inside the Anglo-American zone, and unable to attract the tribes outside Mahabad itself to the nationalist cause.[131] As a result, when the Soviets withdrew from Iran in December 1946, government forces were able to enter Mahabad unopposed when the tribes betrayed the republic.[131]

Several Marxist insurgencies continued for decades (1967, 1979, 1989–96) led by KDP-I and Komalah, but those two organization have never advocated a Kurdish country as did the PKK in Turkey.[133][147][148][149] Still, many dissident leaders, among others Qazi Muhammad and Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou, were executed or assassinated.[131] During Iran–Iraq War, Tehran has provided support for Iraqi-based Kurdish groups like KDP or PUK, along with asylum for 1,400,000 Iraqi refugees, mostly Kurds. Although Kurdish Marxist groups have been marginalized in Iran since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, in 2004 new insurrection has been started by PJAK, separatist organization affiliated with the Turkey-based PKK[150] and designated as terrorist by Iran, Turkey and the United States.[150] Some analysts claim that the PJAK does not pose any serious threat to the government of Iran.[151] Cease-fire has been established in September 2011 following the Iranian offensive on PJAK bases, but several clashes between PJAK and IRGC took place after it.[152] Since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, accusations of discrimination by Western organizations and of foreign involvement by the Iranian side have become very frequent.[152]

Kurds have been well integrated in Iranian political life during the reign of various governments.[133] Kurdish liberal political Karim Sanjabi has served as minister of education under Mohammad Mossadegh in 1952.[141] During the reign of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi some members of parliament and high army officers were Kurds, and there was even a Kurdish Cabinet Minister.[133] During Pahlavi reign Kurds allegedly received many favours from the authorities, for instance to keep their land after the land reforms of 1962.[133] In the early 2000s, the supposed presence of thirty Kurdish deputies in the 290-strong parliament has allegedly shown that Kurds have a say in Iranian politics.[153] Some of influential Kurdish politicians during recent years include former first vice president Mohammad Reza Rahimi and Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, Mayor of Tehran and second-placed presidential candidate in 2013. Kurdish language is today used more than at any other time since the Revolution, including in several newspapers and among schoolchildren.[153] Large numbers of Kurds in Iran show no interest in Kurdish nationalism,[131] especially Shia Kurds, and even vigorously reject the idea of autonomy, preferring direct rule from Tehran.[131][147] Iranian national identity is questioned only in the peripheral Kurdish Sunni regions.[154]

Syria

Kurds and other Non-Arabs account for ten percent of Syria's population, a total of around 1.9 million people.[155] This makes them the largest ethnic minority in the country. They are mostly concentrated in the northeast and the north, but there are also significant Kurdish populations in Aleppo and Damascus. Kurds often speak Kurdish in public, unless all those present do not. Kurdish human rights activists are mistreated and persecuted.[156] No political parties are allowed for any group, Kurdish or otherwise.

Techniques used to suppress the ethnic identity of Kurds in Syria include various bans on the use of the Kurdish language, refusal to register children with Kurdish names, the replacement of Kurdish place names with new names in Arabic, the prohibition of businesses that do not have Arabic names, the prohibition of Kurdish private schools, and the prohibition of books and other materials written in Kurdish.[157][158] Having been denied the right to Syrian nationality, around 300,000 Kurds have been deprived of any social rights, in violation of international law.[159][160] As a consequence, these Kurds are in effect trapped within Syria.[157] In February 2006, however, sources reported that Syria was now planning to grant these Kurds citizenship.[160]

On 12 March 2004, beginning at a stadium in Qamishli (a city in northeastern Syria where many Kurds live), clashes between Kurds and Syrians broke out and continued over a number of days. At least thirty people were killed and more than 160 injured. The unrest spread to other Kurdish inhabited towns along the northern border with Turkey, and then to Damascus and Aleppo.[161][162]

Armenia

Between the 1920s and 1990s, Armenia was a part of the Soviet Union, within which Kurds, like other ethnic groups, had the status of a protected minority. Armenian Kurds were permitted their own state-sponsored newspaper, radio broadcasts and cultural events. During the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, many non-Yazidis and Kurds were forced to leave their homes. Following the end of the Soviet Union, Kurds in Armenia were stripped of their cultural privileges and most fled to Russia or Western Europe.[163] Recently introduced Electoral System of the Armenian National Assembly reserves one seat in the parliament to the representative of the Kurdish minority.[164]

Republic of Azerbaijan

In 1920, two Kurdish-inhabited areas of Jewanshir (capital Kalbajar) and eastern Zangazur (capital Lachin) were combined to form the Kurdistan Okrug (or "Red Kurdistan"). The period of existence of the Kurdish administration was brief and did not last beyond 1929. Kurds subsequently faced many repressive measures, including deportations. As a result of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, many Kurdish areas have been destroyed and more than 150,000 Kurds have been deported by the Armenian forces since 1988.[163]

Kurds In Jordan, Syria, Egypt and Lebanon

The Kurdish leader Saladin along with his uncles Ameer Adil and Ameer Sherko, were joined by Kurdish fighters from the cities of Tigrit, Mosul, Erbil and Sharazur in a drive towards 'Sham' (today's Syria and Lebanon) in order to protect Islamic lands against crusader attack. The Kurdish King and his uncles ruled north Iraq, Jordan, Syria and Egypt for a short period.[Note 21][Note 22][168] Salah El Din in Syria, Ameer Sherko in Egypt and Ameer Adil in Jordan, with family members ruling most of the cities of today's Iraq. The Kurds built many monumental castles in the lands which they ruled, especially in what was called 'Kurdistan of Syria' and in Damuscus, the capital of Syria. A tall building, called 'Qalha', is still standing, in the mid south-west quarter of Damascus. The Ayubian dynasty continued there for many years, all from Kurdish descent.

Genetics

Although the Kurds came under the successive dominion of various conquerors, including the Armenians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Ottoman Turks, Sassanid Persians, and Achaemenid Persians[169] they may have remained relatively unmixed by the influx of invaders, because of their protected and inhospitable mountainous homeland.[170]

Similarity to Europeans and peoples of the Caucasus

A study by Richards and colleagues of mitochondrial DNA in the Near East found that Kurds, Azerbaijanis, Ossetians and Armenians show a high incidence of mtDNA U5 lineages, which are common among Europeans, although rare elsewhere in the Near East. The sample of Kurds in this study came from northwest Iran and northeast Iraq, where Kurds usually predominate.[171]

A geographically broad study of the Southwest and Central Asian Corridor found that populations located west of the Indus Valley mainly harbor mtDNAs of Western Eurasian origin.[172]

When Ivan Nasidze and his colleagues examined both mitochondrial and Y chromosome DNA, they found Kurdish groups most similar genetically to other West Asian groups, and most distant from Central Asian groups, for both mtDNA and the Y chromosome. However, Kurdish groups show a closer relationship with European groups than with Caucasian groups based on mtDNA, but the opposite based on the Y chromosome, indicating some differences in their maternal and paternal histories.[173]

Similarity to Azerbaijanis of Iran

According to DRB1, DQA1 and DQB1 allele frequencies showed a strong genetic tie between Kurds and Azerbaijanis of Iran. According to the current results, present-day Kurds and Azerbaijanis of Iran seem to belong to a common genetic pool.[174]

Similarity to Georgian people

David Comas and colleagues found that mitochondrial sequence pools in Georgians and Kurds are very similar, despite their different linguistic and prehistoric backgrounds. Both populations present mtDNA lineages that clearly belong to the Western Eurasian gene pool.[175]

Similarity to Jewish people

In 2001 Nebel et al. compared three Jewish and three non-Jewish groups from the Middle East: Ashkenazim, Sephardim, and Kurdish Jews from Israel; Muslim Arabs from Israel and the Palestinian Authority Area; Bedouin from the Negev; and Muslim Kurds. They concluded that Kurdish and Sephardi Jews were indistinguishable from one another, whereas both differed slightly, yet noticeably, from Ashkenazi Jews. Nebel et al. had earlier (2000) found a large genetic relationship between Jews and Palestinian Arabs, but in this study found an even higher relationship of Jews with Iraqi Kurds. They conclude that the common genetic background shared by Jews and other Middle Eastern groups predates the division of Middle Easterners into different ethnic groups.[176]

Nebel et al. (2001) also found that the Cohen modal haplotype, considered the most definitive Jewish haplotype, was found among 10.1% of Kurdish Jews, 7.6% of Ashkenazim, 6.4% of Sephardim, 2.1% of Palestinian Arabs, and 1.1% of Kurds. The Cohen modal haplotype and the most frequent Kurdish haplotype were the same on five markers (out of six) and very close on the other marker. The most frequent Kurdish haplotype was shared by 9.5% of Kurds, 2.6% of Sephardim, 2.0% of Kurdish Jews, 1.4% of Palestinian Arabs, and 1.3% of Ashkenazim. The general conclusion is that these similarities result mostly from the sharing of ancient genetic patterns, and not from more recent admixture between the groups.[176]

See also

- History of Iraqi Kurdistan

- List of Kurdish dynasties and countries

- Timeline of Kurdish uprisings

Explanatory notes

- Books from the early Islamic era, including those containing legends like the Shahnameh and the Middle Persian Kar-Namag i Ardashir i Pabagan and other early Islamic sources provide early attestation of the term kurd in the sense of "Iranian nomads". A. The term Kurd in the Middle Persian documents simply means nomad and tent-dweller and could be attributed to any Iranian ethnic group having similar characteristics.[4] G. "It is clear that kurt in all the contexts has a distinct social sense, "nomad, tent-dweller". "The Pahlavi materials clearly show that kurd in pre-Islamic Iran was a social label, still a long way off from becoming an ethnonym or a term denoting a distinct group of people"[5]

- "The ethnic label "Kurd" is first encountered in Arabic sources from the first centuries of the Islamic era; it seemed to refer to a specific variety of pastoral nomadism, and possibly to a set of political units, rather than to a linguistic group: once or twice, "Arabic Kurds" are mentioned. By the 10th century, the term appears to denote nomadic and/or transhumant groups speaking an Iranian language and mainly inhabiting the mountainous areas to the South of Lake Van and Lake Urmia, with some offshoots in the Caucasus.... If there was a Kurdish-speaking subjected peasantry at that time, the term was not yet used to include them."[6]

- "Evidently, the most reasonable explanation of this ethnonym must be sought for in its possible connections with the Cyrtii (Cyrtaei) of the Classical authors."[14]

- The development of the Kurdish language as a separate dialect group within Northwest Iranian seems to follow a similar time-frame; linguistic innovations characteristic of the Kurdish group date to the New Iranian period (10th century onward). Texts that are identifiably Kurdish first appear in the 16th century. See Paul (2008): "Any attempt to study or describe the history of the Kurdish (Kd.) language(s) faces the problem that, from Old and Middle Iranian times, no predecessors of the Kurdish language are yet known; the extant Kurdish texts may be traced back to no earlier than the 16th century CE. [...] The following sound changes do not—from the available evidence—occur before the NIr. period. The change of postvocalic *-m > -v/-w (N-/C-Kd.) is one of the most characteristic features of Kurdish (e.g., in Kd. nāv/nāw “name”). It occurs also in a small number of other WIr. idioms like Vafsī and in certain N- Balōči dialects"[15]

- "The term Kurd in the middle ages was applied to all nomads of Iranian origin"[16]

- "If we take a leap forward to the Arab conquest we find that the name Kurd has taken a new meaning becoming practically synonymous with 'nomad', if nothing more pejorative"[17]

- "We thus find that about the period of the Arab conquest a single ethnic term Kurd (plur. Akrād ) was beginning to be applied to an amalgamation of Iranian or iranicised tribes."[18]

- "The Kurds mentioned in the classical and medieval sources were bona fide ethnic Kurds, and the forbearers of the modern Kurds and/or those who have acquired separate ethnic identities in the southern Zagros since the end of the medieval period."[19]

- Paul (2008) writes about the problem of attaining a coherent definition of "Kurdish language" within the Northwestern Iranian dialect continuum.[15] "There is no unambiguous evolution of Kurdish from Middle Iranian, as "from Old and Middle Iranian times, no predecessors of the Kurdish language are yet known; the extant Kurdish texts may be traced back to no earlier than the 16th century CE." Paul further states: "Linguistics itself, or dialectology, does not provide any general or straightforward definition of at which point a language becomes a dialect (or vice versa). To attain a fuller understanding of the difficulties and questions that are raised by the issue of the 'Kurdish language', it is therefore necessary to consider also non-linguistic factors."[15]

- "The Kurds are undoubtedly of heterogeneous origins. Many people lived in what is now Kurdistan during the past millennia and almost all of the [sic?] them have disappeared as ethnic or linguistic groups.", p. 117: "It is certainly not true that all tribes in Kurdistan have a common origin."[21]

- "The Kurds, an Iranian people of the Near East, live at the junction of more or less laicised Turkey". Excerpt 2: "The classification of the Kurds among the Iranian nations is based mainly on linguistic and historical data and does not prejudice the fact there is a complexity of ethnical elements incorporated in them" Excerpt 3: "We thus find that about the period of the Arab conquest a single ethnic term Kurd (plur. Akrād ) was beginning to be applied to an amalgamation of Iranian or iranicised tribes. Among the latter, some were autochthonous (the Ḳardū; the Tmorik̲h̲/Ṭamurāyē in the district of which Alḳī = Elk was the capital; the Χοθα̑ίται [= al-Ḵh̲uwayt̲h̲iyya] in the canton of Ḵh̲oyt of Sāsūn, the Orṭāyē [= al-Arṭān] in the bend of the Euphrates); some were Semites (cf. the popular genealogies of the Kurd tribes) and some probably Armenian (it is said that the Mamakān tribe is of Mamikonian origin)." Excerpt 4: "In the 20th century, the existence of an Iranian non-Kurdish element among the Kurds has been definitely established (the Gūrān-Zāzā group)."[22]

- Dandamaev considers Carduchi (who were from the upper Tigris near the Assyrian and Median borders) less likely than Cyrtians as ancestors of modern Kurds: "It has repeatedly been argued that the Carduchi were the ancestors of the Kurds, but the Cyrtii (Kurtioi) mentioned by Polybius, Livy, and Strabo (see MacKenzie, pp. 68–69) are more likely candidates."[26] However, according to McDowall, the term Cyrtii was first applied to Seleucid or Parthian mercenary slingers from Zagros, and it is not clear if it denoted a coherent linguistic or ethnic group.[29]

- "It is true that during their revolutionary phase (1447–1501), Safavi guides had played on their descent from the family of the Prophet. The hagiography of the founder of the Safavi order, Shaykh Safi al-Din Safvat al-Safa written by Ibn Bazzaz in 1350-was tampered with during this very phase. An initial stage of revisions saw the transformation of Safavi identity as Sunni Kurds into Arab blood descendants of Muhammad."[54][55]

- "But the origins of the family of Shaykh Safi al-Din go back not to the Hijaz but to Kurdistan, from where, seven generations before him, Firuz Shah Zarin-kulah had migrated to Adharbayjan."[57]

- "The Safavid family's base of power sprang from a Sufi order, and the name of the order came from its founder Shaykh Safi al-Din. The Shaykh's family had been resident in Azerbaijan since Saljuk times and then in Ardabil, and was probably Kurdish in origin."[58]

- The Safavid order had been founded by Shaykh Safi al-Din (1252–1334), a man of uncertain but probably Kurdish origin[59]

-

- "The Safawid was originally a Sufi order whose founder, Shaykh Safi al-Din (1252–1334) was a Sunni Sufi master from a Kurdish family in north-west Iran"[60]

- the Turcophone Safavid family of Ardabil in Azerbaijan, probably of Turkicized Iranian (perhaps Kurdish), origin[61]

- "From the evidence available at the present time, it is certain that the Safavid family was of indigenous Iranian stock, and not of Turkish ancestry as it is sometimes claimed. It is probable that the family originated in Persian Kurdistan, and later moved to Azerbaijan, where they adopted the Azari form of Turkish spoken there, and eventually settled in the small town of Ardabil sometimes during the eleventh century.[62]

- Quote from the Kurdish rebel website: "On 20 May at 14:00–19:45 part of Medya Defense area; Şehit Beritan, Şekif, Lelikan, Gundê Cennetê, Helikopter Hill and Xinerê area was air attacked were made by Turkish military aircraft. Result of this attacked four of our friends has reached the martyr. As soon as we have solid information about our friends identity we will let the public know."[126]

- A number of contemporary sources make note of this. The biographer Ibn Khallikan writes, "Historians agree in stating that [Saladin's] father and family belonged to Duwin [Dvin]....They were Kurds and belonged to the Rawādiya (sic), which is a branch of the great tribe al-Hadāniya"[165] The medieval historian Ibn Athir relates a passage from another commander: "... both you and Saladin are Kurds and you will not let power pass into the hands of the Turks"[166]

- "Saladin was a Kurd from Tikrit."[167]

References

- Izady, Mehrdad R. (1992). The Kurds: A Concise Handbook. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8448-1727-9.

- Shoup, John A. (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598843637.

- Nezan, Kendal. A Brief Survey of the History of the Kurds. Kurdish Institute of Paris.

- Safrastian, Kurds and Kurdistan, The Harvill Press, 1948, pp. 16, 31.

- Asatrian, Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds, Iran and the Caucasus, Vol. 13, pp. 1–58, 2009.

- Martin van Bruinessen, "The ethnic identity of the Kurds", in: Ethnic groups in the Republic of Turkey, compiled and edited by Peter Alford Andrews with Rüdiger Benninghaus [=Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients, Reihe B, Nr.60]. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwich Reichert, 1989, pp. 613–21. Archived 15 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Driver, G. R. "The Name Kurd and Its Philological Connexions": 401.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hakan Ozoglu, Kurdish notables and the Ottoman State, 2004, SUNY Press, 186 pp., ISBN 0-7914-5993-4 (See p. 23)

- G. S. Reynolds, "A Reflection on Two Qurʾānic Words (Iblīs and Jūdī), with Attention to the Theories of A. Mingana", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 124, No. 4 (October –December , 2004), pp. 675–689. (see pp. 683, 684 & 687)

- Ilya Gershevitch, William Bayne Fisher, The Cambridge History of Iran: The Median and Achamenian Periods, 964 pp., Cambridge University Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2, (see footnote of p. 257)

- Revue des études arméniennes, vol. 21, 1988–1989, p. 281, By Société des études armeniennes, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Published by Imprimerie nationale, P. Geuthner, 1989.

- Mark Marciak Sophene, Gordyene, and Adiabene: Three Regna Minora of Northern Mesopotamia Between East and West, 2017. pp. 220-221

- Victoria Arekelova, Garnik S. Asatryan Prolegomena To The Study Of The Kurds, Iran and The Caucasus, 2009 pp. 82

- G. Asatrian, Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds, Iran and the Caucasus, Vol. 13, pp. 1–58, 2009

- Ludwig Paul "History of the Kurdish Language", Encyclopedia Iranica (2008)

- Wladimir Ivanon, The Gabrdi dialect spoken by the Zoroastrians of Persia, Published by G. Bardim 1940. pg 42)

- David N. Mackenzie, "The Origin of Kurdish", Transactions of the Philological Society, 1961, pp 68–86.

- "Kurds" in Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2007. Brill Online. accessed 2007.

- Izady, Mehrdad (1992). The Kurds: A Concise Handbook. The Kurds: A Concise History And Fact Book. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-8448-1727-9.

- Izady, Mehrdad R (1992). The Kurds: A concise handbook. Taylor & Francis. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8448-1727-9.

- M. Van Bruinessen, Agha, Shaikh and State, 373 pp., Zed Books, 1992. p. 122:

- "Excerpt 1: Bois, Th.; Minorsky, V.; Bois, Th.; Bois, Th.; MacKenzie, D. N.; Bois, Th. "Kurds, Kurdistan". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C. E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W. P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2009. Brill Online". Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- Thomas Bois, The Kurds, 159 pp., 1966. (see p. 10)

- Prokhorov, Aleksandr Mikhaĭlovich (1973). Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Macmillan.

- The Encyclopedia Americana. Americana Corporation. 1972. ISBN 978-0-7172-0103-7.

- Encyclopedia Iranica, "Carduchi" by M. Dandamayev

- Schmitz, Leonhard (1859). A Manual of Ancient Geography: With a Map Showing the Retreat of the 10,000 Greeks Under Xenophon. Blanchard and Lea.

- Ilya Gershevitch, William Bayne Fisher, The Cambridge History of Iran: The Median and Achamenian Periods, 964 pp., Cambridge University Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2, (see footnote of p. 257)

- David McDowall, A modern history of the Kurds, 515 pp., I.B. Tauris, 2004, ISBN 978-1-85043-416-0 (see p. 9)

- David N. Mackenzie, "The Origin of Kurdish", Transactions of Philological Society, 1961

- P. Tedesco (1921: 255)

- Professor Garnik Asatrian (Yerevan University) (2009). "Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds", Iran and the Caucasus, Vol. 13, pp. 1–58, 2009.

- "HAZĀRASPIDS". www.iranicaonline.org. Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

HAZĀRASPIDS, a local dynasty of Kurdish origin which ruled in the Zagros mountains region of southwestern Persia,...

- "Who Are the Kurds?". Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- http://www.bakhawan.com/dotkurd/nebez/Inglizi/TheKurds.pdf, p. 55

- Bozarslan, Hamit; Gunes, Cengiz; Yadirgi, Veli, eds. (22 April 2021). The Cambridge History of the Kurds (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108623711. ISBN 978-1-108-62371-1. S2CID 243594800.

- Hancock, Lee (2004). Saladin and the Kingdom of Jerusalem: The Muslims Recapture the Holy Land in AD 1187. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8239-4217-6.

- James, B. Saladin et les Kurdes: Perceptions d’un Groupe au Temps des Croisades. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2006.

- James, B. Saladin et les Kurdes: Perceptions d’un Groupe au Temps des Croisades. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2006. P. 52.

- Van Renterghem, Vanessa, "Invisibles ou absents? Questions sur la présence kurde à Baghdad aux Ve-VIe/XIe-XIIe Siècles," Etudes Kurdes 10, (2009): 21–52.

- Le Strange, Guy. (1905) The Lands of the Eastern Caliphate. Cambridge: London. P. 12.

- ARCHITECTURAL IDENTITY IN CONTEMPORARY CAIRO. Azbakiyya, the Lake, the Garden, or the Forgotten Place.

- Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society

- Cohen, Amnon; Lewis, Bernard (1978). Population and Revenue in the Towns of Palestine in the Sixteenth Century. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09375-X.

- Haldimann, Marc-André; Humbert, Jean-Baptiste (2007). Gaza: à la croisée des civilisations: contexte archéologique et historique. CHAMAN Edition. ISBN 978-2-9700435-5-3.

- Teller, Matthew (2022). Nine Quarters of Jerusalem. Profile Books. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-78283-904-0.

Bikur Holim Street, named for the Bikur Holim Jewish hospital that operated here from 1864 to 1947. But the Arabic on the same signs names the alley as Tariq Haret al-Sharaf ('Sharaf Quarter Road') […] Mujir ad-Din records that before Haret al-Sharaf the same neighbourhood was known as the Kurdish quarter.

- Adar Arnon, “The Quarters of Jerusalem in the Ottoman Period,” Middle Eastern Studies 28, no. 1 (January 1992): 1–65

- Nimrod Luz. The Mamluk City in the Middle East: History, Culture, and the Urban Landscape. 2014. P. 93

- Nimrod Luz. The Mamluk City in the Middle East: History, Culture, and the Urban Landscape. 2014. P. 135

- Heinz Halm, Shi'a Islam, translated by Janet Watson. New Material translated by Marian Hill, 2nd edition, Columbia University Press, p. 75

- Ira Marvin Lapidus. A History of Islamic Societies, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 233

- Tapper, Richard, Frontier Nomads of Iran. A political and social history of the Shahsevan. Cambridge, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997. pp 39.

- Izady, Mehrdad, The Kurds: A Concise Handbook. Taylor & Francis, Inc., Washington, D.C. 1992. pp 50

- E. Yarshater, Encyclopædia Iranica, "The Iranian Language of Azerbaijan"

- Kathryn Babayan, Mystics, Monarchs and Messiahs: Cultural Landscapes of Early Modern Iran, Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press, 2002. pg 143

- Emeri van Donzel, Islamic Desk Reference compiled from the Encyclopedia of Islam, E.J. Brill, 1994, pp 381

- Farhad Daftary, Intellectual Traditions in Islam, I.B.Tauris, 2000. pp 147

- Gene Ralph Garthwaite, The Persians, Blackwell Publishing, 2004. pg 159 : Chapter on Safavids.

- Elton L. Daniel, The History of Iran, Greenwood Press, 2000. pg 83

- Muhammad Kamal, Mulla Sadra's Transcendent Philosophy, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006. pg 24

- John R. Perry, "Turkic-Iranian contacts", Encyclopædia Iranica, 24 January 2006.

- Roger M. Savory. "Safavids" in Peter Burke, Irfan Habib, Halil Inalci: History of Humanity-Scientific and Cultural Development: From the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century, Taylor & Francis. 1999. Excerpt from pg 259

- "The Creation of the Ṣafawí Power to 930/1524. Sháh Isma'íl and His Ancestors". The Literary History of Persia. p. 37. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2006.

- Matthee, Rudolph (Rudi). "Unwalled Cities and Restless Nomads: Firearms and Artillery in Safavid Iran".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Covel, Michael. "Khorasan: People of the Mountains in the Land of the Sun".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - JOHN R. PERRY; A. Shapur Shahbazi, Erich Kettenhofen. "DEPORTATIONS". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- John Perry, Forced Migration in Iran During the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Iranian Studies, VIII-4, 1975.

- Mehrdad R. Izady. "Deportations & Forced Resettlements". The Kurds: A Concise Handbook. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2006.

- Dawrizhetsʻi, Aṛakʻel (2005). The History of Vardapet Aṛakʻel of Tabriz. Mazda Publishers. p. 77. ISBN 9781568591827.

- DIMDIM Archived 11 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Eskandar Beg Monshi (1979). History of Shah Abbas the Great History of Shah Abbas the Great. Mazda. ISBN 978-0-89158-296-0.

- O. Dzh. Dzhalilov, Kurdski geroicheski epos "Zlatoruki Khan" (The Kurdish heroic epic "Gold-hand Khan"), Moscow, 1967, pp. 5–26, 37–39, 206.

- Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh, The Image Of An Ottoman City: Imperial Architecture And Urban Experience In Aleppo In The 16th And 17th Centuries, BRILL, 2004, ISBN 9789004124547, p. 123

- Bruce Masters, The Arabs of the Ottoman Empire, 1516–1918: A Social and Cultural History, Cambridge University Press, 2013, ISBN 1107067790, p. 38

- H. J. Kissling, B. Spuler, N. Barbour, J. S. Trimingham, H. Braun, H. Hartel,The Last Great Muslim Empires, Vol. III, BRILL, 1997, ISBN 9789004021044, p. 70

- Caroline Finkel, Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire, Basic Books, 2007, ISBN 9780465008506, p. 179

- James J. Reid, Rozhîkî Revolt, 1065/1655, Journal of Kurdish Studies, Vol. 3, pp. 13–40, 2000.

- James J. Reid, Batak 1876: a massacre and its significance, Journal of Genocide Research, 2(3), pp. 375–409, 2000.

- Meiselas, Susan (1998). Kurdistan: in the Shadow of History. Random House. ISBN 9780679423898.

- Shields, Sarah D. (22 June 2000). Mosul before Iraq: Like Bees Making Five-Sided Cells. SUNY Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7914-4488-7.

- Taylor, Gordon (1 May 2007). Fever and Thirst: An American Doctor Among the Tribes of Kurdistan, 1835-1844. Chicago Review Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-89733-657-4.

- W. G. Elphinston, "The Kurdish Question", Journal of International Affairs, Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1946, p. 93

- "Ozgur Politika". Archived from the original on 21 January 2004. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- C. Dahlman, The Political Geography of Kurdistan, Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2002, p. 278

- Bloxham, Donald (2007). The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0199226887.

- McDowall, David (1997). A Modern History of the Kurds. London: I.B.Tauris. p. 2. ISBN 1-86064-185-7.

- Laçiner, Bal; Bal, Ihsan (2004). "The Ideological And Historical Roots Of Kurdist Movements In Turkey: Ethnicity Demography, Politics". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 10 (3): 473–504. doi:10.1080/13537110490518282. S2CID 144607707. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- Natali, Denise (2004). "Ottoman Kurds and emergent Kurdish nationalism". Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies. 13 (3): 383–387. doi:10.1080/1066992042000300701. S2CID 220375529.

- TBMM Gizli Celse Zabıtları Vol. 3 p. 551, Ankara, 1985

- Mehmet Emin Zeki, Kürdistan Tarihi p. 20, Ankara, 1992

- Garo Sasuni, Kürt Ulusal Hareketleri ve 15. Yüzyıldan Günümüze Kürt-Ermeni İlişkileri p. 331, Istanbul, 1992

- C. Dahlman, The Political Geography of Kurdistan, Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2002, p. 279

- "(McDowall - A Modern History of the Kurds, page 492)"

- Kurdish Culture and Society: An Annotated Bibliography - P. 22. by Lokman I. Meho, Kelly L. Maglaughlin

- O'Grady, Siobhán (10 October 2019). "Actually, President Trump, some Kurds did fight in World War II". Washington Post.

- "Assyrian RAF Levies". Assyrian RAF Levies.

- Hawramy, Fazel (13 October 2019). "Kurdish WWII veterans: Trump wasn't born when we fought the Nazis". Rudaw. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- J. Otto Pohl (October 2017). "Kurds in the USSR, 1917-1956". Kurdish Studies. pp. 39–40.

- Fortin, Jacey (10 October 2019). "Trump Says the Kurds "Didn't Help" at Normandy. Here's the History". New York Times.

- "CIA World Factbook". Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- "The cultural situation of the Kurds" Archived 24 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine A report by Lord Russell-Johnston, Council of Europe, July 2006

- "Ethnologue census of languages in Asian portion of Turkey". Archived from the original on 18 October 2011.

- Arin, Kubilay Yado, "Turkey and the Kurds – From War to Reconciliation?" UC Berkeley Center for Right Wing Studies Working Paper Series, 26 March 2015.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor; Göçek, Fatma Müge; Gocek, Fatma Muge; Naimark, Norman M.; Naimark, Robert and Florence McDonnell Professor of East European Studies Norman M. (23 February 2011). A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-539374-3.

- Üngör, Umut. "Young Turk social engineering : mass violence and the nation state in eastern Turkey, 1913- 1950" (PDF). University of Amsterdam. p. 247. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Bayir, Derya (22 April 2016). Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law. Routledge. pp. 139–141. ISBN 978-1-317-09579-8.

- "Leyla Zana, Prisoner of Conscience". New York: Amnesty International USA. Archived from the original on 10 May 2005.

- Radu Michael (2001). "The Rise and Fall of the PKK". Orbis. 45 (1): 47–64. doi:10.1016/s0030-4387(00)00057-0.

- "Turkey: "Still Critical" – Introduction". Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- "Displaced and Disregarded: Turkey's Failing Village Return Program". Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- "Prospects in 2005 for Internally Displaced Kurds in Turkey". Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- HRW Turkey Reports Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

See also: Report D612, October 1994, "Forced Displacement of Ethnic Kurds" (A Human Rights Watch Publication). - Yerilgoz, Yucel. "The Practice of a Century – Kemalism". Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Archived from the original on 9 March 2002.