Nestorius

Nestorius (/ˌnɛsˈtɔːriəs/; in Ancient Greek: Νεστόριος; c. 386 – c. 451) was the Archbishop of Constantinople from 10 April 428 to August 431. A Christian theologian, several of his teachings in the fields of Christology and Mariology were seen as controversial and caused major disputes. He was condemned and deposed from his see by the Council of Ephesus, the third Ecumenical Council, in 431.[1]

Mar Nestorius | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Nestorius | |

| Archbishop of Constantinople | |

| Born | c. 386 Germanicia, Province of Syria, Roman Empire (now Kahramanmaraş, Turkey) |

| Died | c. 451 (aged 64 or 65) Great Oasis of Hibis (al-Khargah), Egypt |

| Venerated in | Assyrian Church of the East Chaldean Syrian Church Ancient Church of the East |

| Feast | October 25,Fifth Friday Of Denha along with Mar Theodore of Mopsuestia and Mar Diodore of Tarsus |

| Controversy | Christology, Theotokos |

His teachings included rejection of the title Theotokos (Mother of God), used for Mary, mother of Jesus, which indicated his preference for the concept of a loose prosopic union of two natures (divine and human) of Christ, over the concept of their full hypostatic union. That brought him into conflict with Cyril of Alexandria and other prominent churchmen of the time, who accused him of heresy.[2]

Nestorius sought to defend himself at the Council of Ephesus in 431, but instead found himself formally condemned for heresy by a majority of the bishops and was subsequently removed from his see. On his own request, he retired to his former monastery, in or near Antioch. In 435, Theodosius II sent him into exile in Upper Egypt, where he lived on until about 451, strenuously defending his views. His last major defender within the Roman Empire, Theodoret of Cyrrhus, finally agreed to anathematize him in 451 during the Council of Chalcedon.

From then on, he had no defenders within the empire, but the Church of the East never accepted his condemnation. That led later to western Christians giving the name Nestorian Church to the Church of the East where his teachings were deemed Orthodox and in line with its own teachings. Nestorius is revered as among three "Greek Teachers" of the Church (in addition to Diodorus of Tarsus and Theodore of Mopsuestia). The Church of the East's Eucharistic Service, which is known to be among the oldest in the world, incorporates prayers attributed to Nestorius himself.

The Second Council of Constantinople of AD 553 confirmed the validity of the condemnation of Nestorius, refuting the letter of Ibas of Edessa which claimed that Nestorius was condemned without due inquiry.[2]

The discovery, translation and publication of his Bazaar of Heracleides at the beginning of the 20th century have led to a reassessment of his theology in western scholarship. It is now generally agreed that his ideas were not far from those that eventually emerged as orthodox, but the orthodoxy of his formulation of the doctrine of Christ is still controversial.

Life

Sources place the birth of Nestorius in either 381 or 386 in the city of Germanicia in the Province of Syria, Roman Empire (now Kahramanmaraş in Turkey).[3]

He received his clerical training as a pupil of Theodore of Mopsuestia in Antioch. He was living as a priest and monk in the monastery of Euprepius near the walls, and he gained a reputation for his sermons that led to his enthronement by Theodosius II, as Patriarch of Constantinople, following the 428 death of Sisinnius I.

Nestorian controversy

Shortly after his arrival in Constantinople, Nestorius became involved in the disputes of two theological factions, which differed in their Christology. Nestorius tried to find a middle ground between those that emphasized the fact that in Christ, God had been born as a man and insisted on calling the Virgin Mary Theotokos (Greek: Θεοτόκος, "God-bearer") and those that rejected that title because God, as an eternal being, could not have been born. Nestorius suggested the title Christotokos (Χριστοτόκος, "Christ-bearer"), but he did not find acceptance on either side.

"Nestorianism" refers to the doctrine that there are two distinct hypostases in the Incarnate Christ, the one Divine and the other human. The teaching of all churches that accept the Council of Ephesus is that in the Incarnate Christ is a single hypostasis, God and man at once. That doctrine is known as the Hypostatic union.

Nestorius's opponents charged him with detaching Christ's divinity and humanity into two persons existing in one body, thereby denying the reality of the Incarnation. It is not clear whether Nestorius actually taught that.

Eusebius, a layman who later became the bishop of the neighbouring Dorylaeum, was the first to accuse Nestorius of heresy,[4] but the most forceful opponent of Nestorius was Patriarch Cyril of Alexandria. This naturally caused great excitement at Constantinople, especially among the clergy, who were clearly not well disposed to Nestorius, the stranger from Antioch.[4]

Cyril appealed to Pope Celestine I to make a decision, and Celestine delegated to Cyril the job of excommunicating Nestorius if he did not change his teachings within 10 days.

Nestorius had arranged with the emperor in the summer of 430 for the assembling of a council. He now hastened it, and the summons had been issued to patriarchs and metropolitans on 19 November, before the pope's sentence, delivered through Cyril of Alexandria, and was served on Nestorius.[4]

Emperor Theodosius II convoked a general church council, at Ephesus, itself a special seat for the veneration of Mary, where the Theotokos formula was popular. The Emperor and his wife supported Nestorius, but Pope Celestine supported Cyril.

Cyril took charge of the First Council of Ephesus in 431, opening debate before the long-overdue contingent of Eastern bishops from Antioch arrived. The council deposed Nestorius and declared him a heretic.

In Nestorius' own words,

When the followers of Cyril saw the vehemence of the emperor... they roused up a disturbance and discord among the people with an outcry, as though the emperor were opposed to God; they rose up against the nobles and the chiefs who acquiesced not in what had been done by them and they were running hither and thither. And... they took with them those who had been separated and removed from the monasteries by reason of their lives and their strange manners and had for this reason been expelled, and all who were of heretical sects and were possessed with fanaticism and with hatred against me. And one passion was in them all, Jews and pagans and all the sects, and they were busying themselves that they should accept without examination the things which were done without examination against me; and at the same time all of them, even those that had participated with me at table and in prayer and in thought, were agreed... against me and vowing vows one with another against me.... In nothing were they divided.

While the council was in progress, John I of Antioch and the eastern bishops arrived and were furious to hear that Nestorius had already been condemned. They convened their own synod, at which Cyril was deposed. Both sides then appealed to the emperor.

Initially, the imperial government ordered both Nestorius and Cyril to be deposed and exiled. Nestorius was made to return to his monastery at Antioch, and Maximian was consecrated Archbishop of Constantinople in his place. Cyril was eventually allowed to return after bribing various courtiers.[5]

Later events

In the following months, 17 bishops who supported Nestorius's doctrine were removed from their sees. Eventually, John I of Antioch was obliged to abandon Nestorius, in March 433. On August 3, 435, Theodosius II issued an imperial edict that exiled Nestorius from the monastery in Antioch in which he had been staying to a monastery in the Great Oasis of Hibis (al-Khargah), in Egypt, securely within the diocese of Cyril. The monastery suffered attacks by desert bandits, and Nestorius was injured in one such raid. Nestorius seems to have survived there until at least 450 (given the evidence of The Book of Heraclides).[6] Nestorius died shortly after the Council of Chalcedon in 451, in Thebaid, Egypt.

Writings

Very few of Nestorius' writings survive. There are several letters preserved in the records of the Council of Ephesus, and fragments of a few others. About 30 sermons are extant, mostly in fragmentary form. The only complete treatise is the lengthy defence of his theological position, The Bazaar of Heraclides, written in exile at the Oasis, which survives in Syriac translation. It must have been written no earlier than 450, as he knows of the death of the Emperor Theodosius II (29 July 450).[7] There is an English translation of this work,[8] but it was criticized as inaccurate, as well as the older French translation.[9] Further scholarly analyses have shown that several early interpolations have been made in the text, sometime in the second half of the 5th century.[10]

Bazaar of Heracleides

In 1895, a 16th-century book manuscript containing a copy of a text written by Nestorius was discovered by American missionaries in the library of the Nestorian patriarch in the mountains at Qudshanis, Hakkari. This book had suffered damage during Muslim conquests, but was substantially intact, and copies were taken secretly. The Syriac translation had the title of the Bazaar of Heracleides.[11] The original 16th-century manuscript was destroyed in 1915 during the Turkish massacres of Assyrian Christians. Edition of this work is primarily to be attributed to the German scholar, Friedrich Loofs, of Halle University.

In the Bazaar, written about 450, Nestorius denies the heresy for which he was condemned and instead affirms of Christ "the same one is twofold"—an expression that some consider similar to the formulation of the Council of Chalcedon. Nestorius' earlier surviving writings, however, including his letter written in response to Cyril's charges against him, contain material that has been interpreted by some to imply that at that time he held that Christ had two persons. Others view this material as merely emphasising the distinction between how the pre-incarnate Logos is the Son of God and how the incarnate Emmanuel, including his physical body, is truly called the Son of God.[8]

Legacy

Though Nestorius had been condemned by the church, there was a faction loyal to him and his teachings. Following the Nestorian Schism and the relocation of many Nestorian Christians to Persia, Nestorian thought became ingrained in the native Christian community, known as the Church of the East, to the extent that it was often known as the "Nestorian Church".

In modern times, the Assyrian Church of the East, a modern descendant of the historical Church of the East, reveres Nestorius as a saint, but the modern church does not subscribe to the entirety of the Nestorian doctrine, as it has traditionally been understood in the West. Patriarch Mar Dinkha IV repudiated the exonym Nestorian on the occasion of his accession in 1976.[12]

During the process of restoration of the Syro-Malabar Catholic Rite in 1957, Pope Pius XII of Rome requested the restoration of the Anaphorae of Theodore of Mopsuestia and Nestorius. The Syro-Malabar Church had historically made use of the Anaphora of Nestorius until it was forcibly latinized by the Portuguese in the Synod of Diamper in 1599.

Advised by the Oriental Congregation, the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church[13] restored all three Anaphorae in the 2010s:

- Addai and Mar Mari, the Apostles of the East

- Theodore of Mopsuestia

- Nestorius of Constantinople

These three Anaphorae, or quddashas, are among the oldest in Christendom. That of Nestorius is reserved for five days in a liturgical year: Denha (Epiphany), the first Friday after Denha (John the Baptist), the fourth Friday of the Denha (the Greek Fathers), the Thursday of Pes’ha (Maundy Thursday) and the Wednesday of the Ascension of Our Lord. That of Theodore is used from the first Sunday of the Weeks of Annunciation to Oshana Sunday (Palm Sunday). On all the other days that of Addai and Mari is used. The Anaphorae are attributed to Nestorius but purportedly Pseudepigrapha and there remains a question of authorship.[14][15] Even though the attributed Anaphora are used in the Syro-Malabar Church, there is no separate commemoration of Nestorius in the liturgical calendar however, as the East Syriac tradition holds Nestorius to be one of the Three Greek Fathers (along with Diodore of Tarsus and Theodore the Intrepreter), he is by virtue of that fact commemorated among them.[16]

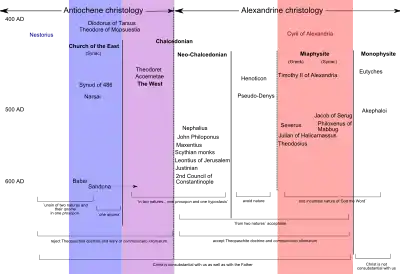

In the Roman Empire, the doctrine of Monophysitism developed in reaction to Nestorianism. The new doctrine asserted that Christ had but one nature, his human nature being absorbed into his divinity. It was condemned at the Council of Chalcedon and was misattributed to the non-Chalcedonian Churches. Today, it is condemned as heresy in the modern Oriental Orthodox churches.

References

- Seleznyov 2010, p. 165–190.

- Meyendorff 1989.

- Louth 2004, p. 348.

- Chapman 1911.

- McEnerney 1987, p. 151.

- Louth 2004, p. 348-349.

- Louth 2004, p. 349.

- Hodgson & Driver 1925.

- Nau, Bedjan & Brière 1910.

- Bevan 2013, p. 31-39.

- "Early Church Fathers - Additional Works in English Translation unavailable elsewhere online".

- Hill 1988, p. 107.

- "The Order of Mar Theodore and Nestorious - English" (PDF).

- Gelston, A. (March 1, 1996). "The origin of the anaphora of Nestorius: Greek or Syriac?". Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 1996;78(3):73-86.

- "3. The Anaphora Of Mar Nestorius". Mar Nestorius and Mar Theodore the Interpreter. Gorgias Press. January 17, 2010. pp. 9–12. doi:10.31826/9781463219710-003. ISBN 9781463219710 – via www.degruyter.com.

- "Syro-Malabar Liturgical Calendar: 2020–2021". Syro-Malabar Major Archiepiscopal Commission for Liturgy.

Sources

- Anastos, Milton V. (1962). "Nestorius Was Orthodox". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 16: 117–140. doi:10.2307/1291160. JSTOR 1291160.

- Bethune-Baker, James F. (1908). Nestorius and His Teaching: A Fresh Examination of the Evidence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107432987.

- Bevan, George A. (2009). "The Last Days of Nestorius in the Syriac Sources". Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies. 7 (2007): 39–54. doi:10.31826/9781463216153-004. ISBN 9781463216153.

- Bevan, George A. (2013). "Interpolations in the Syriac Translation of Nestorius' Liber Heraclidis". Studia Patristica. 68: 31–39.

- Braaten, Carl E. (1963). "Modern Interpretations of Nestorius". Church History. 32 (3): 251–267. doi:10.2307/3162772. JSTOR 3162772. S2CID 162735558.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1996). "The 'Nestorian' Church: A Lamentable Misnomer" (PDF). Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 78 (3): 23–35. doi:10.7227/BJRL.78.3.3.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1999). "The Christology of the Church of the East in the Synods of the Fifth to Early Seventh Centuries: Preliminary Considerations and Materials". Doctrinal Diversity: Varieties of Early Christianity. New York and London: Garland Publishing. pp. 281–298. ISBN 9780815330714.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006). Fire from Heaven: Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754659082.

- Burgess, Stanley M. (1989). The Holy Spirit: Eastern Christian Traditions. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 9780913573815.

- Chapman, John (1911). "Nestorius and Nestorianism". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Chesnut, Roberta C. (1978). "The Two Prosopa in Nestorius' Bazaar of Heracleides". The Journal of Theological Studies. 29 (2): 392–409. doi:10.1093/jts/XXIX.2.392.

- Edwards, Mark (2009). Catholicity and Heresy in the Early Church. Farnham: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754662914.

- González, Justo L. (2005). Essential Theological Terms. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664228101.

- McGuckin, John A. (1994). St. Cyril of Alexandria: The Christological Controversy: Its History, Theology, and Texts. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004312906.

- Grillmeier, Aloys (1975) [1965]. Christ in Christian Tradition: From the Apostolic Age to Chalcedon (451) (2nd revised ed.). Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664223014.

- Hill, Henry, ed. (1988). Light from the East: A Symposium on the Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Churches. Toronto: Anglican Book Centre. ISBN 9780919891906.

- Hodgson, Leonard; Driver, Godfrey R., eds. (1925). Nestorius: The Bazaar of Heracleides. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9781725202399.

- Kuhn, Michael F. (2019). God is One: A Christian Defence of Divine Unity in the Muslim Golden Age. Carlisle: Langham Publishing. ISBN 9781783685776.

- Loon, Hans van (2009). The Dyophysite Christology of Cyril of Alexandria. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9004173224.

- Loofs, Friedrich (1914). Nestorius and his Place in the History of Christian Doctrine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107450769.

- Louth, Andrew (2004). "John Chrysostom to Theodoret of Cyrrhus". The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 342–352. ISBN 9780521460835.

- McEnerney, John I. (1987). St. Cyril of Alexandria Letters 51–110. Washington: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 9780813215143.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial Unity and Christian Divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410563.

- Nau, François; Bedjan, Paul; Brière, Maurice, eds. (1910). Nestorius: Le livre d'Héraclide de Damas. Paris: Letouzey et Ané.

- Norris, Richard A., ed. (1980). The Christological Controversy. Minneapolis: Fortess Press. ISBN 9780800614119.

- Pásztori-Kupán, István (2006). Theodoret of Cyrus. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781134391769.

- Reinink, Gerrit J. (1995). "Edessa Grew Dim and Nisibis Shone Forth: The School of Nisibis at the Transition of the Sixth-Seventh Century". Centres of Learning: Learning and Location in Pre-modern Europe and the Near East. Leiden: Brill. pp. 77–89. ISBN 9004101934.</ref>

- Reinink, Gerrit J. (2009). "Tradition and the Formation of the 'Nestorian' Identity in Sixth- to Seventh-Century Iraq". Church History and Religious Culture. 89 (1–3): 217–250. doi:10.1163/187124109X407916. JSTOR 23932289.

- Seleznyov, Nikolai N. (2010). "Nestorius of Constantinople: Condemnation, Suppression, Veneration: With special reference to the role of his name in East-Syriac Christianity". Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. 62 (3–4): 165–190.

- Wessel, Susan (2004). Cyril of Alexandria and the Nestorian Controversy: The Making of a Saint and of a Heretic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926846-7.

External links

- Nestorius at Orthodoxwiki.org

- Dialogue between the Syrian and Assyrian Churches from the Coptic Church

- The Coptic Church's View Concerning Nestorius

- English translation of the Bazaar of Heracleides.

- Writing of Nestorius

- "The lynching of Nestorius" by Stephen M. Ulrich, concentrates on the political pressures around the Council of Ephesus and analyzes the rediscovered Bazaar of Nestorius.

- The Person and Teachings of Nestorius of Constantinople by Mar Bawai Soro.