Opal

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silica (SiO2·nH2O); its water content may range from 3 to 21% by weight, but is usually between 6 and 10%. Due to its amorphous property, it is classified as a mineraloid, unlike crystalline forms of silica, which are considered minerals. It is deposited at a relatively low temperature and may occur in the fissures of almost any kind of rock, being most commonly found with limonite, sandstone, rhyolite, marl, and basalt.

| Opal | |

|---|---|

A rich seam of iridescent opal encased in matrix | |

| General | |

| Category | Mineraloid |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Hydrated silica. SiO2·nH2O |

| IMA symbol | Opl[1] |

| Crystal system | Amorphous[2] |

| Identification | |

| Color | Colorless, white, yellow, red, orange, green, brown, black, blue, pink |

| Crystal habit | Irregular veins, in masses, in nodules |

| Cleavage | None[2] |

| Fracture | Conchoidal to uneven[2] |

| Mohs scale hardness | 5.5–6[2] |

| Luster | Subvitreous to waxy[2] |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | opaque, translucent, transparent |

| Specific gravity | 2.15+0.08 −0.90[2] |

| Density | 2.09 g/cm3 |

| Polish luster | Vitreous to resinous[2] |

| Optical properties | Single refractive, often anomalous double refractive due to strain[2] |

| Refractive index | 1.450+0.020 −0.080 Mexican opal may read as low as 1.37, but typically reads 1.42–1.43[2] |

| Birefringence | none[2] |

| Pleochroism | None[2] |

| Ultraviolet fluorescence | black or white body color: inert to white to moderate light blue, green, or yellow in long and short wave, may also phosphoresce, common opal: inert to strong green or yellowish green in long and short wave, may phosphoresce; fire opal: inert to moderate greenish brown in long and short wave, may phosphoresce[2] |

| Absorption spectra | green stones: 660 nm, 470 nm cutoff[2] |

| Diagnostic features | darkening upon heating |

| Solubility | hot salt water, bases, methanol, humic acid, hydrofluoric acid |

| References | [3][4] |

The name opal is believed to be derived from the Sanskrit word upala (उपल), which means 'jewel', and later the Greek derivative opállios (ὀπάλλιος), which means 'to see a change in color'.

There are two broad classes of opal: precious and common. Precious opal displays play-of-color (iridescence); common opal does not.[5] Play-of-color is defined as "a pseudo chromatic optical effect resulting in flashes of colored light from certain minerals, as they are turned in white light."[6] The internal structure of precious opal causes it to diffract light, resulting in play-of-color. Depending on the conditions in which it formed, opal may be transparent, translucent, or opaque, and the background color may be white, black, or nearly any color of the visual spectrum. Black opal is considered the rarest, while white, gray, and green opals are the most common.

Precious opal

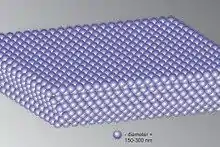

Precious opal shows a variable interplay of internal colors, and though it is a mineraloid, it has an internal structure. At microscopic scales, precious opal is composed of silica spheres some 150–300 nanometres (5.9×10−6–1.18×10−5 in) in diameter in a hexagonal or cubic close-packed lattice. It was shown by J. V. Sanders in the mid-1960s[7][8] that these ordered silica spheres produce the internal colors by causing the interference and diffraction of light passing through the microstructure of the opal.[9] The regularity of the sizes and the packing of these spheres is a prime determinant of the quality of precious opal. Where the distance between the regularly packed planes of spheres is around half the wavelength of a component of visible light, the light of that wavelength may be subject to diffraction from the grating created by the stacked planes. The colors that are observed are determined by the spacing between the planes and the orientation of planes with respect to the incident light. The process can be described by Bragg's law of diffraction.

Visible light cannot pass through large thicknesses of the opal. This is the basis of the optical band gap in a photonic crystal. The notion that opals are photonic crystals for visible light was expressed in 1995 by Vasily Astratov's group.[10] In addition, microfractures may be filled with secondary silica and form thin lamellae inside the opal during its formation. The term Opalescence is commonly used to describe this unique and beautiful phenomenon, which in gemology is termed play of color. In gemology, opalescence is applied to the hazy-milky-turbid sheen of common or potch opal which does not show a play of color. Opalescence is a form of adularescence.

For gemstone use, most opal is cut and polished to form a cabochon. "Natural" opal refers to polished stones consisting wholly of precious opal. Opals too thin to produce a "Natural" opal may be combined with other materials to form "composite" gems. An opal doublet consists of a relatively thin layer of precious opal, backed by a layer of dark-colored material, most commonly ironstone, dark or black common opal (potch), onyx, or obsidian. The darker backing emphasizes the play of color and results in a more attractive display than a lighter potch. An opal triplet is similar to a doublet but has a third layer, a domed cap of clear quartz or plastic on the top. The cap takes a high polish and acts as a protective layer for the opal. The top layer also acts as a magnifier, to emphasize the play of color of the opal beneath, which is often an inferior specimen or an extremely thin section of precious opal. Triplet opals tend to have a more artificial appearance and are not classed as precious gemstones, but rather "composite" gemstones. Jewelry applications of precious opal can be somewhat limited by opal's sensitivity to heat due primarily to its relatively high water content and predisposition to scratching.[11] Combined with modern techniques of polishing, a doublet opal can produce a similar effect to Natural black or boulder opal at a fraction of the price. Doublet opal also has the added benefit of having genuine opal as the top visible and touchable layer, unlike triplet opals.

Common opal

Besides the gemstone varieties that show a play of color, the other kinds of common opal include the milk opal, milky bluish to greenish (which can sometimes be of gemstone quality); resin opal, which is honey-yellow with a resinous luster; wood opal, which is caused by the replacement of the organic material in wood with opal;[12] menilite, which is brown or grey; hyalite, a colorless glass-clear opal sometimes called Muller's glass; geyserite, also called siliceous sinter, deposited around hot springs or geysers; and diatomaceous earth, the accumulations of diatom shells or tests. Common opal often displays a hazy-milky-turbid sheen from within the stone. In gemology, this optical effect is strictly defined as opalescence which is a form of adularescence.

Other varieties of opal

Fire opal is a transparent to translucent opal, with warm body colors of yellow to orange to red. Although it does not usually show any play of color, occasionally a stone will exhibit bright green flashes. The most famous source of fire opals is the state of Querétaro in Mexico; these opals are commonly called Mexican fire opals. Fire opals that do not show a play of color are sometimes referred to as jelly opals. Mexican opals are sometimes cut in their rhyolitic host material if it is hard enough to allow cutting and polishing. This type of Mexican opal is referred to as a Cantera opal. Another type of opal from Mexico, referred to as Mexican water opal, is a colorless opal that exhibits either a bluish or golden internal sheen.[14]

Girasol opal is a term sometimes mistakenly and improperly used to refer to fire opals, as well as a type of transparent to semitransparent type milky quartz from Madagascar which displays an asterism, or star effect when cut properly. However, the true girasol opal[14] is a type of hyalite opal that exhibits a bluish glow or sheen that follows the light source around. It is not a play of color as seen in precious opal, but rather an effect from microscopic inclusions. It is also sometimes referred to as water opal, too, when it is from Mexico. The two most notable locations of this type of opal are Oregon and Mexico.

Peruvian opal (also called blue opal) is a semi-opaque to opaque blue-green stone found in Peru, which is often cut to include the matrix in the more opaque stones. It does not display a play of color. Blue opal also comes from Oregon and Idaho in the Owyhee region, as well as from Nevada around the Virgin Valley.[15]

Opal is also formed by diatoms. Diatoms are a form of algae that, when they die, often form layers at the bottoms of lakes, bays, or oceans. Their cell walls are made up of hydrated silicon dioxide which gives them structural coloration and therefore the appearance of tiny opals when viewed under a microscope. These cell walls or "tests" form the “grains” for the diatomaceous earth. This sedimentary rock is white, opaque, and chalky in texture.[16] Diatomite has multiple industrial uses such as filtering or adsorbing since it has a fine particle size and very porous nature, and gardening to increase water absorption.

History

Opal was rare and very valuable in antiquity. In Europe, it was a gem prized by royalty.[17][18] Until the opening of vast deposits in Australia in the 19th century the only known source was Červenica beyond the Roman frontier in Slovakia.[19] Opal is the national gemstone of Australia.[20]

Sources

The primary sources of opal are Australia and Ethiopia, but because of inconsistent and widely varying accountings of their respective levels of extraction, it is difficult to accurately state what proportion of the global supply of opal comes from either country. Australian opal has been cited as accounting for 95–97% of the world's supply of precious opal,[22][23] with the state of South Australia accounting for 80% of the world's supply.[24] In 2012, Ethiopian opal production was estimated to be 14,000 kg (31,000 lb) by the United States Geological Survey.[25] USGS data from the same period (2012), reveals Australian opal production to be $41 million.[26] Because of the units of measurement, it is not possible to directly compare Australian and Ethiopian opal production, but these data and others suggest that the traditional percentages given for Australian opal production may be overstated.[27] Yet, the validity of data in the USGS report appears to conflict with that of Laurs et al. and Mesfin, who estimated the 2012 Ethiopian opal output (from Wegal Tena) to be only 750 kg (1,650 lb).

Australia

The town of Coober Pedy in South Australia is a major source of opal. The world's largest and most valuable gem opal "Olympic Australis" was found in August 1956 at the "Eight Mile" opal field in Coober Pedy. It weighs 17,000 carats (3.4 kg; 7.5 lb) and is 11 inches (280 mm) long, with a height of 4+3⁄4 in (120 mm) and a width of 4+1⁄2 in (110 mm).[28]

The Mintabie Opal Field in South Australia located about 250 km (160 mi) northwest of Coober Pedy has also produced large quantities of crystal opal and the rarer black opal. Over the years, it has been sold overseas incorrectly as Coober Pedy opal. The black opal is said to be some of the best examples found in Australia.

Andamooka in South Australia is also a major producer of matrix opal, crystal opal, and black opal. Another Australian town, Lightning Ridge in New South Wales, is the main source of black opal, opal containing a predominantly dark background (dark gray to blue-black displaying the play of color), collected from the Griman Creek Formation.[29] Boulder opal consists of concretions and fracture fillings in a dark siliceous ironstone matrix. It is found sporadically in western Queensland, from Kynuna in the north, to Yowah and Koroit in the south.[30] Its largest quantities are found around Jundah and Quilpie in South West Queensland. Australia also has opalized fossil remains, including dinosaur bones in New South Wales[31] and South Australia,[32] and marine creatures in South Australia.[33]

Ethiopia

It has been reported that Northern African opal was used to make tools as early as 4000 BC. The first published report of gem opal from Ethiopia appeared in 1994, with the discovery of precious opal in the Menz Gishe District, North Shewa Province.[34] The opal, found mostly in the form of nodules, was of volcanic origin and was found predominantly within weathered layers of rhyolite.[35] This Shewa Province opal was mostly dark brown in color and had a tendency to crack. These qualities made it unpopular in the gem trade. In 2008, a new opal deposit was found approximately 180 km north of Shewa Province, near the town of Wegel Tena, in Ethiopia's Wollo Province. The Wollo Province opal was different from the previous Ethiopian opal finds in that it more closely resembled the sedimentary opals of Australia and Brazil, with a light background and often vivid play-of-color.[36] Wollo Province opal, more commonly referred to as "Welo" or "Wello" opal, has become the dominant Ethiopian opal in the gem trade.[37]

Virgin Valley, Nevada

The Virgin Valley[38] opal fields of Humboldt County in northern Nevada produce a wide variety of precious black, crystal, white, fire, and lemon opal. The black fire opal is the official gemstone of Nevada. Most of the precious opal is partial wood replacement. The precious opal is hosted and found in situ within a subsurface horizon or zone of bentonite, which is considered a "lode" deposit. Opals which have weathered out of the in situ deposits are alluvial and considered placer deposits. Miocene-age opalised teeth, bones, fish, and a snake head have been found. Some of the opal has high water content and may desiccate and crack when dried. The largest producing mines of Virgin Valley have been the famous Rainbow Ridge,[39] Royal Peacock,[40] Bonanza,[41] Opal Queen,[42] and WRT Stonetree/Black Beauty[43] mines. The largest unpolished black opal in the Smithsonian Institution, known as the "Roebling opal",[44] came out of the tunneled portion of the Rainbow Ridge Mine in 1917, and weighs 2,585 carats (517.0 g; 18.24 oz). The largest polished black opal in the Smithsonian Institution comes from the Royal Peacock opal mine in the Virgin Valley, weighing 160 carats (32 g; 1.1 oz), known as the "Black Peacock".[45]

Mexico

Opal occurs in significant quantity and variety in central Mexico, where mining and production first originated in the state of Querétaro. In this region the opal deposits are located mainly in the mountain ranges of three municipalities: Colón, Tequisquiapan and Ezequiel Montes. During the 1960s through to the mid-1970s, the Querétaro mines were heavily mined. Today's opal miners report that it was much easier to find quality opals with a lot of fire and play of color back then, whereas today the gem-quality opals are very hard to come by and command hundreds of US dollars or more. They gave an orangey opaque lustre, which is called the "Mexican fire opal".

The oldest mine in Querétaro is Santa Maria del Iris. This mine was opened around 1870 and has been reopened at least 28 times since. At the moment there are about 100 mines in the regions around Querétaro, but most of them are now closed. The best quality of opals came from the mine Santa Maria del Iris, followed by La Hacienda la Esperanza, Fuentezuelas, La Carbonera, and La Trinidad. Important deposits in the state of Jalisco were not discovered until the late 1950s.

In 1957, Alfonso Ramirez (of Querétaro) accidentally discovered the first opal mine in Jalisco: La Unica, located on the outer area of the volcano of Tequila, near the Huitzicilapan farm in Magdalena. By 1960 there were around 500 known opal mines in this region alone. Other regions of the country that also produce opals (of lesser quality) are Guerrero, which produces an opaque opal similar to the opals from Australia (some of these opals are carefully treated with heat to improve their colors so high-quality opals from this area may be suspect). There are also some small opal mines in Morelos, Durango, Chihuahua, Baja California, Guanajuato, Puebla, Michoacán, and Estado de México.

Other locations

Another source of white base opal or creamy opal in the United States is Spencer, Idaho.[46] A high percentage of the opal found there occurs in thin layers.

Other significant deposits of precious opal around the world can be found in the Czech Republic, Canada, Slovakia, Hungary, Turkey, Indonesia, Brazil (in Pedro II, Piauí[47]), Honduras (more precisely in Erandique), Guatemala and Nicaragua.

In late 2008, NASA announced it had discovered opal deposits on Mars.[48]

Synthetic opal

Opals of all varieties have been synthesized experimentally and commercially. The discovery of the ordered sphere structure of precious opal led to its synthesis by Pierre Gilson in 1974.[9] The resulting material is distinguishable from natural opal by its regularity; under magnification, the patches of color are seen to be arranged in a "lizard skin" or "chicken wire" pattern. Furthermore, synthetic opals do not fluoresce under ultraviolet light. Synthetics are also generally lower in density and are often highly porous.

Opals which have been created in a laboratory are often termed "lab-created opals", which, while classifiable as man-made and synthetic, are very different from their resin-based counterparts which are also considered man-made and synthetic. The term "synthetic" implies that a stone has been created to be chemically and structurally indistinguishable from a genuine one, and genuine opal contains no resins or polymers. The finest modern lab-created opals do not exhibit the lizard skin or columnar patterning of earlier lab-created varieties, and their patterns are non-directional. They can still be distinguished from genuine opals, however, by their lack of inclusions and the absence of any surrounding non-opal matrix. While many genuine opals are cut and polished without a matrix, the presence of irregularities in their play-of-color continues to mark them as distinct from even the best lab-created synthetics.

Other research in macroporous structures have yielded highly ordered materials that have similar optical properties to opals and have been used in cosmetics.[49] Synthetic opals are also deeply investigated in photonics for sensing and light management purposes.[50][51]

Local atomic structure of opals

The lattice of spheres of opal that cause interference with light is several hundred times larger than the fundamental structure of crystalline silica. As a mineraloid, no unit cell describes the structure of opal. Nevertheless, opals can be roughly divided into those that show no signs of crystalline order (amorphous opal) and those that show signs of the beginning of crystalline order, commonly termed cryptocrystalline or microcrystalline opal.[52] Dehydration experiments and infrared spectroscopy have shown that most of the H2O in the formula of SiO2·nH2O of opals is present in the familiar form of clusters of molecular water. Isolated water molecules, and silanols, structures such as SiOH, generally form a lesser proportion of the total and can reside near the surface or in defects inside the opal.

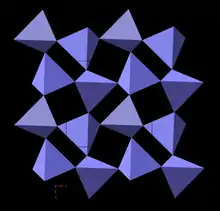

The structure of low-pressure polymorphs of anhydrous silica consists of frameworks of fully corner bonded tetrahedra of SiO4. The higher temperature polymorphs of silica cristobalite and tridymite are frequently the first to crystallize from amorphous anhydrous silica, and the local structures of microcrystalline opals also appear to be closer to that of cristobalite and tridymite than to quartz. The structures of tridymite and cristobalite are closely related and can be described as hexagonal and cubic close-packed layers. It is therefore possible to have intermediate structures in which the layers are not regularly stacked.

Microcrystalline opal

Microcrystalline opal or Opal-CT has been interpreted as consisting of clusters of stacked cristobalite and tridymite over very short length scales. The spheres of opal in microcrystalline opal are themselves made up of tiny nanocrystalline blades of cristobalite and tridymite. Microcrystalline opal has occasionally been further subdivided in the literature. Water content may be as high as 10 wt%.[53] Opal-CT, also called lussatine or lussatite, is interpreted as consisting of localized order of α-cristobalite with a lot of stacking disorder. Typical water content is about 1.5 wt%.

Noncrystalline opal

Two broad categories of noncrystalline opals, sometimes just referred to as "opal-A" ("A" stands for "amorphous"),[54] have been proposed. The first of these is opal-AG consisting of aggregated spheres of silica, with water filling the space in between. Precious opal and potch opal are generally varieties of this, the difference being in the regularity of the sizes of the spheres and their packing. The second "opal-A" is opal-AN or water-containing amorphous silica-glass. Hyalite is another name for this.

Noncrystalline silica in siliceous sediments is reported to gradually transform to opal-CT and then opal-C as a result of diagenesis, due to the increasing overburden pressure in sedimentary rocks, as some of the stacking disorder is removed.[55]

Opal surface chemical groups

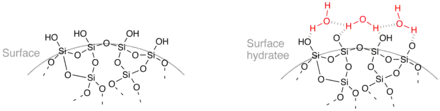

The surface of opal in contact with water is covered by siloxane bonds (≡Si–O–Si≡) and silanol groups (≡Si–OH). This makes the opal surface very hydrophilic and capable of forming numerous hydrogen bonds.

Etymology

The word 'opal' is adapted from the Latin term opalus. The origin of this word in turn is a matter of debate, but most modern references suggest it is adapted from the Sanskrit word úpala.[56]

References to the gem are made by Pliny the Elder. It is suggested to have been adapted from Ops, the wife of Saturn, and goddess of fertility. The portion of Saturnalia devoted to Ops was "Opalia", similar to opalus.

Another common claim that the term is adapted from the Ancient Greek word, opallios. This word has two meanings, one is related to "seeing" and forms the basis of the English words like "opaque"; the other is "other" as in "alias" and "alter". It is claimed that opalus combined these uses, meaning "to see a change in color". However, historians have noted the first appearances of opallios do not occur until after the Romans had taken over the Greek states in 180 BC and they had previously used the term paederos.[56]

However, the argument for the Sanskrit origin is strong. The term first appears in Roman references around 250 BC, at a time when the opal was valued above all other gems. The opals were supplied by traders from the Bosporus, who claimed the gems were being supplied from India. Before this, the stone was referred to by a variety of names, but these fell from use after 250 BC.

Historical superstitions

In the Middle Ages, opal was considered a stone that could provide great luck because it was believed to possess all the virtues of each gemstone whose color was represented in the color spectrum of the opal.[57] It was also said to grant invisibility if wrapped in a fresh bay leaf and held in the hand.[57][58] As a result, the opal was seen as the patron gemstone for thieves during the medieval period.[59] Following the publication of Sir Walter Scott's Anne of Geierstein in 1829, opal acquired a less auspicious reputation. In Scott's novel, the Baroness of Arnheim wears an opal talisman with supernatural powers. When a drop of holy water falls on the talisman, the opal turns into a colorless stone and the Baroness dies soon thereafter. Due to the popularity of Scott's novel, people began to associate opals with bad luck and death.[57] Within a year of the publishing of Scott's novel in April 1829, the sale of opals in Europe dropped by 50%, and remained low for the next 20 years or so.[60]

Even as recently as the beginning of the 20th century, it was believed that when a Russian saw an opal among other goods offered for sale, he or she should not buy anything more, as the opal was believed to embody the evil eye.[57]

Opal is considered the birthstone for people born in October.[61]

Examples

- The Olympic Australis, the world's largest and most valuable gem opal, found in Coober Pedy[62][63]

- The Andamooka Opal, presented to Queen Elizabeth II, also known as the Queen's Opal

- The Addyman Plesiosaur from Andamooka, "the finest known opalised skeleton on Earth"[33]

- The Burning of Troy, the now-lost opal presented to Joséphine de Beauharnais by Napoleon I of France and the first named opal[64]

- The Flame Queen Opal

- The Halley's Comet Opal, the world's largest uncut black opal

- Although the clock faces above the information stand in Grand Central Terminal in New York City are often said to be opal, they are in fact opalescent glass

- The Roebling Opal, Smithsonian Institution[65]

- The Galaxy Opal, listed as the "World's Largest Polished Opal" in the 1992 Guinness Book of Records[66]

- The Rainbow Virgin, "the finest crystal opal specimen ever unearthed"[67][68][69]

- The Sea of Opal, the largest black opal in the world [70]

- The Fire of Australia, assumed to be "the finest uncut opal in existence"[69][71]

- Beverly the Bug, the first known example of an opal with an insect inclusion

See also

- Biogenic silica

- Cacholong

- Foil opal

- Labradorite

- Opalite

- Optical phenomena – Observable events that result from the interaction of light and matter

- Uncut Gems (2019 film)

References

- Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- Gemological Institute of America, GIA Gem Reference Guide 1995, ISBN 0-87311-019-6

- "Opal". Webmineral. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- "Opal". Mindat.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- "Opal Description". Gemological Institute of America. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- "Glossary: Play of Color". Mindat. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Sanders, J. V. (1964). "Colour of precious opal". Nature. 204 (496): 1151–1153. Bibcode:1964Natur.204.1151S. doi:10.1038/2041151a0. S2CID 4169953.

- Sanders, J. V. (1968). "Diffraction of light by opals". Acta Crystallographica A. 24 (4): 427–434. Bibcode:1968AcCrA..24..427S. doi:10.1107/S0567739468000860.

- Klein, Cornelis; Hurlbut, Cornelius S. (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20th ed.). ISBN 978-0-471-80580-9.

- Astratov, V. N.; Bogomolov, V. N.; Kaplyanskii, A. A.; Prokofiev, A. V.; Samoilovich, L. A.; Samoilovich, S. M.; Vlasov, Yu. A. (1995). "Optical spectroscopy of opal matrices with CdS embedded in its pores: Quantum confinement and photonic band gap effects". Il Nuovo Cimento D. 17 (11–12): 1349–1354. Bibcode:1995NCimD..17.1349A. doi:10.1007/bf02457208. S2CID 121167426.

- Dr. Joel Arem; Donald Clark, CSM IMG (23 June 2015). "Opal Value, Price, and Jewelry". Gemsociety.org. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Gribble, C. D. (1988). "Tektosilicates (framework silicates)". Rutley's Elements of Mineralogy (27th ed.). London: Unwin Hyman. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-04-549011-0.

- Downing, Paul B. (1992). Opal Identification and Value. pp. 55–61.

- Swisher, James; Anthony, Edna B. "Let's Talk Gemstones: Opal". Archived from the original on 7 November 2011.

- "Opal – Nevada Mining Association". www.nevadamining.org. 19 December 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "diatomite - The Mineral and Gemstone Kingdom". www.minerals.net. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "The central stone on the thirteenth-century crown of the Holy Roman Emperor was an opal said to be the color of pure white snow, sparkling with splashes of bright red wine: it was called "the Orphanus," perhaps because there was no other stone like it.24 And on New Year’s Day 1584,25 Queen Elizabeth I was delighted to receive an opal parure—a full set of matching jewelry—from one of her favorite courtiers, Sir Christopher Hatton." Finlay, Victoria. Jewels: A Secret History (Kindle Locations 2145-2148). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

- "All of these early stones were almost certainly from the ancient mines of Slovakia—the same source as Nonius’ precious stone and the Holy Roman Emperor’s red-and-white one. The mines were worked until the late nineteenth century..." Finlay, Victoria. Jewels: A Secret History (Kindle Locations 2163-2165). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

- Finlay, Victoria. Jewels: A Secret History (Kindle Location 1871). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

- "Australian National Gemstone". Australian Government, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- "Yowah Nut: Yowah Nut mineral information and data". Mindat.org. 20 February 2011. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- "Gemstone". It's an Honour. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 29 January 2011.

- "Rapaport Magazine – A Designer Stone". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- "Opal – South Australia's Gemstone". Government of South Australia. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- Yager, Thomas R. (1 December 2013), "The Mineral Industry of Ethiopia", United States Geological Survey, 2012 Minerals Yearbook (PDF), pp. 17.1–17.5, archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2014

- Tse, Pui-Kwan (1 December 2013), "The Mineral Industry of Australia", United States Geological Survey, 2012 Minerals Yearbook (PDF), pp. 3.1–3.27, archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2014, retrieved 20 September 2014

- "Rapaport Magazine – Ethiopian Opal". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- Cram, Len (2006). A history of South Australian opal, 1840–2005. Lightning Ridge, NSW. ISBN 978-0975721407.

- Osborne, Zoe; Kitanov, Alex (17 July 2022). "The black-opal hunters of outback Australia". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- "Queensland opal". Archived from the original on 13 October 2007.

- First dinosaur named in NSW in nearly a century after chance discovery ABC News, 5 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Rare dinosaur fossil discovered on internet after disappearing for decades ABC News, 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Opal Fossils". South Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Barot, N. (1994). "New precious opal deposit found in Ethiopia". ICA Gazette.

- Johnson, Mary L.; Kammerling, Robert C.; DeGhionno, Dino G.; Koivula, John I. (Summer 1996). "Opal from Shewa Province, Ethiopia". Gems & Gemology. 32 (2): 112–120. doi:10.5741/GEMS.32.2.112.

- Rondeau, Benjamin (Summer 2010). "Play-of-color from Wegel Tena, Wollo Province, Ethiopia". Gems & Gemology. doi:10.5741/GEMS.46.2.90.

- Gashaw, Yidneka (8 April 2012). "Opal Trade Transforms North Wollo". Addis Fortune. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014.

- "Virgin Valley District, Humboldt Co., Nevada". mindat.org. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012.

- "Rainbow Ridge Mine". mindat.org. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012.

- "Royal Peacock Group Mines, Virgin Valley District, Humboldt Co., Nevada". mindat.org. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012.

- "Bonanza Opal Workings (Virgin Opal), Virgin Valley District, Humboldt Co., Nevada". mindat.org. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012.

- "Opal Queen group, Virgin Valley District, Humboldt Co., Nevada". mindat.org. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012.

- "Stonetree Opal Mine, WRT Stonetree group, Virgin Valley District, Humboldt Co., Nevada". mindat.org. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012.

- "Roebling Opal". National Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012.

- "Opal". Lapidary Journal: 1522, 1542. March 1971.

- "If you've ever wanted an opal -- it's time to visit Spencer | East Idaho News". East Idaho News. 6 August 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- "Boi Morto Mine, Pedro II, Piauí, Brazil". Mindat.org. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- "NASA probe finds opals in Martian crevices". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 19 January 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- "Macroporous Structures, Metal Oxides, Highly Ordered". Office for Technology Commercialization, Technology Marketing Site. University of Minnesota. 25 June 2010. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- Lova, Paola; Congiu, Simone; Sparnacci, Katia; Angelini, Angelo; Boarino, Luca; Laus, Michele; Stasio, Francesco Di; Comoretto, Davide (8 April 2020). "Core–shell silica–rhodamine B nanosphere for synthetic opals: from fluorescence spectral redistribution to sensing". RSC Advances. 10 (25): 14958–14964. Bibcode:2020RSCAd..1014958L. doi:10.1039/D0RA02245D. ISSN 2046-2069. PMC 9052040. PMID 35497145.

- Tétreault, N.; Míguez, H.; Ozin, G. A. (2004). "Silicon Inverse Opal—A Platform for Photonic Bandgap Research". Advanced Materials. 16 (16): 1471–1476. doi:10.1002/adma.200400618. ISSN 1521-4095. S2CID 137194866.

- Graetsch, H. (1994). Heaney, P. J.; Prewitt, Connecticut; Gibbs, G. V. (eds.). "Structural characteristics of opaline and microcrystalline silica minerals. Silica, physical behavior, geochemistry and materials applications". Reviews in Mineralogy. 29.

- Opal-CT on Midat

- Wilson, M.J. (2014). "The structure of opal-CT revisited". Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 405: 68. Bibcode:2014JNCS..405...68W. doi:10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2014.08.052. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- Cady, S. L.; Wenk, H.-R.; Downing, K. H. (1996). "HRTEM of microcrystalline opal in chert and porcelanite from the Monterey Formation, California" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 81 (11–12): 1380–1395. Bibcode:1996AmMin..81.1380C. doi:10.2138/am-1996-11-1211. S2CID 53527412. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2011.

- Eckert, Allan W. (1997). The World of Opals. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 56–57. ISBN 9780471133971. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016.

- Fernie, William Thomas (1907). Precious Stones for Curative Wear. Bristol: John Wright & Co. pp. 248–249.

- Dunwich, Gerina (1996). Wicca Candle Magick. pp. 84–85.

- "Opal Symbolism and Legends". International Gem Society. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- Eckert, Allan W. (1997). "A Chronological History and Mythology of Opals". The World of Opals. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 53–118.

- Goldberg-Gist, Arlene (2003). "What's that Stuff? Opal". Chemical & Engineering News. 81 (4). doi:10.1021/cen-v081n004.p058.

- Leechman, F; The opal book, University of California Press, 1961

- opalsdownunder.com.au

- Eckert, Allan W. (1997). The World of Opals. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 67, 126. ISBN 978-0-471-13397-1.

- "The Dynamic Earth". National Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- Guinness, Medd (October 1992). "The Guinness Book of Records 1993. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-85112-978-5. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016.

- "Million-dollar opal Rainbow Virgin to go on display at SA exhibition celebrating centenary". ABC News. 2 August 2015. Archived from the original on 17 December 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- "Opals media releases". South Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- "$4 million worth of the South Australian Museum's opal collection for display in Qatar". South Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 17 December 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- "Largest black opal in the world". 25 October 2016. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- "World's finest piece of uncut opal finds new home at the South Australian Museum". South Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

External links

- Farlang opal Hist. References Localities, anecdotes by Theophrastus, Isaac Newton, Georg Agricola etc.

- ICA's Opal Page: International Colored Stone Association

- Opal Fossils from the South Australian Museum Archived 13 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 19 October 2016.

- Opal Mineral data and specimen images Mineralogy Database

- Opalworld Australian Opal Fields – Map of precious opal deposits