Ozymandias

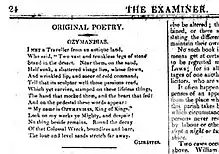

"Ozymandias" (/ˌɒziˈmændiəs/ OZ-ee-MAN-dee-əs)[1] is a sonnet written by the English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822). It was first published in the 11 January 1818 issue of The Examiner[2] of London. The poem was included the following year in Shelley's collection Rosalind and Helen, A Modern Eclogue; with Other Poems,[3] and in a posthumous compilation of his poems published in 1826.[4]

| Ozymandias (Shelley) | |

|---|---|

| by Percy Bysshe Shelley | |

Shelley's "Ozymandias" in The Examiner | |

| First published in | 11 January 1818 |

| Country | England |

| Language | Modern English |

| Form | Sonnet |

| Meter | Loose iambic pentameter |

| Rhyme scheme | ABABACDCEDEFEF |

| Publisher | The Examiner |

| Full text | |

Shelley wrote the poem in friendly competition with his friend and fellow poet Horace Smith (1779–1849), who also wrote a sonnet on the same topic with the same title. The poem explores the fate of history and the ravages of time: even the greatest men and the empires they forge are impermanent, their legacies fated to decay into oblivion.

Origin

In antiquity, Ozymandias was a Greek name for the pharaoh Ramesses II (r. 1279–1213 BC), derived from a part of his throne name, Usermaatre. In 1817, Shelley began writing the poem "Ozymandias", after the British Museum acquired the Younger Memnon, a head-and-torso fragment of a statue of Ramesses II, which dated from the 13th century BC. Earlier, in 1816, the Italian archeologist Giovanni Battista Belzoni had removed the 7.25-short-ton (6.58 t; 6,580 kg) statue fragment from the Ramesseum, the mortuary temple of Ramesses II at Thebes, Egypt. The reputation of the statue fragment preceded its arrival to Western Europe; after his Egyptian expedition in 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte had failed to acquire the Younger Memnon for France.[5] Although the British Museum expected delivery of the antiquity in 1818, the Younger Memnon did not arrive in London until 1821.[6][7] Shelley published his poems before the statue fragment of Ozymandias arrived in Britain,[7] and the view of modern scholarship is that Shelley never saw the statue, although he might have learned about it from news reports, as it was well known even in its previous location near Luxor.[8]

The book Les Ruines, ou méditations sur les révolutions des empires (1791) by Constantin François de Chassebœuf, comte de Volney (1757–1820), first published in an English translation as The Ruins, or a Survey of the Revolutions of Empires (London: Joseph Johnson, 1792) by James Marshall, was an influence on Shelley.[9] Shelley had explored similar themes in his 1813 work Queen Mab. Typically, Shelley published his literary works either anonymously or pseudonymously, under the name "Glirastes", a Graeco-Latin name created by combining the Latin glīs ("dormouse") with the Greek suffix ἐραστής (erastēs, "lover");[10] the Glirastes name referred to his wife, Mary Shelley, whom he nicknamed "dormouse".[11]

Writing, publication and text

Publication history

The banker and political writer Horace Smith spent the Christmas season of 1817–1818 with Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Shelley. At this time, members of the Shelleys' literary circle would sometimes challenge each other to write competing sonnets on a common subject: Shelley, John Keats and Leigh Hunt wrote competing sonnets about the Nile around the same time. Shelley and Smith both chose a passage from the writings of the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus in Bibliotheca historica, which described a massive Egyptian statue and quoted its inscription: "King of Kings Ozymandias am I. If any want to know how great I am and where I lie, let him outdo me in my work." In Shelley's poem, Diodorus becomes "a traveller from an antique land."[12][lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3]

Shelley wrote the poem quickly[13] around Christmas in 1817[14]—either in December that year or early January 1818.[15] The poem was printed in The Examiner,[2] a weekly paper published by Leigh's brother John Hunt in London. Hunt admired Shelley's poetry and many of his other works, such as The Revolt of Islam, were published in The Examiner.[16]

Shelley's poem was published on 11 January 1818 under the pen name "Glirastes".[10] The name meant "lover of dormice", dormouse being his pet name for his spouse.[17] Smith's sonnet of the same name was published several weeks later.[13] Shelley's poem appeared on page 24 in the yearly collection, under Original Poetry. It appeared again in Shelley's 1819 collection Rosalind and Helen, A Modern Eclogue; with Other Poems,[18] which was republished in 1876 under the title "Sonnet. Ozymandias" by Charles and James Ollier[3] and in the 1826 Miscellaneous and Posthumous Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley by William Benbow, both in London.[4]

Text

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desart.[lower-alpha 4] Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

"My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!"

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.— Percy Shelley, "Ozymandias", 1819 edition[18]

Analysis and interpretation

Shelley's "Ozymandias" is a sonnet, written in loose iambic pentameter, but with an atypical rhyme scheme[20] (ABABACDC EDEFEF) which violates the rule that there should be no connection in rhyme between the octave and the sestet.

Two themes of the "Ozymandias" poems are the inevitable decline of rulers and their pretensions to greatness.[21]

The rhyme scheme reflects the interlocking stories of poem's four narrative voices, which are its "I", the "traveller" (an exemplar of the sort of travel literature author whose works Shelley would have encountered), the statue's "architect", and the statue's subject himself.[22] The "I met a traveller who […]" framing of the poem is an instance of the "once upon a time" storytelling device.[20]

Scholars such as professors Nora Crook and Newman White have viewed the work as critical of Shelley's contemporaries George IV, with the statue's legs a coded reference to the then Prince Regent's gout and possible sexually-transmitted diseases, and Napoleon Bonaparte.[23][24] That the poem is connected to Napoleon is indeed the 21st century accepted reading.[25]

Byron scholar Peter Cochran asserted the poem to be "a lesson to tyrants", listing Napeoleon, George IV, Metternich, Tsar Alexander, Emperor Francis, and Castlereagh.[26][27] Jalal Uddin Khan connects it, in addition, to Muammar Gaddafi's statement that he was Africa's "king of kings".[28] That it connects in people's minds to rulers who post-date Shelley is illustrated by incidents such as the one CNN journalist who reported the aerial bombing of Iraq in 1991 signing off the report with the final three lines of the poem.[26]

Other real historic persons to have referred to themselves in such terms include Ashurbanipal who had "I am a hero; I am gigantic; I am colossal; I am magnificent." carved in stone, and Menli I Giray who styled himself "Sovereign of Two Continents and Khan of Khans of the Two Seas".[29]

The tragic fall of powerful men is a theme common in literature, from Giovanni Boccaccio's De Casibus Virorum Illustrium through John Lydgate's The Fall of Princes to Geoffrey Chaucer's The Monk's Tale.[30] Modern scholarship is that Byron's Childe Harold Canto 3, which was about the fall of Napoleon and whose manuscript Shelley had himself transported to Byron's publisher John Murray, was also a prompt for the poem.[31]

Like Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Kubla Khan and Shelley's own Alastor, the poem can be viewed in the context of a wave of Orientalism prevalent in Western Europe, helped along by such events as Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1798 and the accompanying Description of Egypt.[32] The imagery of the statue's harsh but commanding bearing is evocative of the Byronic hero, and professor Hadley J. Mozer has gone further in suggesting that Shelley was describing Byron's own 1814 portrait by George Henry Harlow.[33][34]

Reception and impact

The poem has been cited as Shelley's "best-known poem"[35] and is generally considered one of his best works,[36] though it is sometimes considered uncharacteristic of his poetry.[37] An article in Alif cited "Ozymandias" as "one of the greatest and most famous poems in the English language".[38] Stephens considered that the Ozymandias Shelley created dramatically altered the opinion of Europeans on the king.[39] Donald P. Ryan wrote that "Ozymandias" "stands above" numerous other poems written about ancient Egypt, particularly its fall and described the sonnet as "a short, insightful commentary on the fall of power".[40]

"Ozymandias" has been included in many poetry anthologies,[36][41] particularly school textbooks,[42] where it is often included because of its perceived simplicity and the relative ease with which it can be memorized.[37] Several poets, including Richard Watson Gilder and John B. Rosenman, have written poems titled "Ozymandias" in response to Shelley's work.[40]

The poem has impacted numerous other works, including Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë.[43] It has been translated into several languages, notably Russian, where Shelley was an influential figure.[44]

In the AMC drama Breaking Bad, the 14th episode of season 5 is titled "Ozymandias." The episode's title alludes to the collapse of protagonist Walter White's drug empire.[45] The media company Ozy was named after the poem,[46] as is the superhero Ozymandias in the comic book series Watchmen.[47]

Notes

- See footnote 10 at the following source, for reference to the Loeb Classical Library translation of this inscription, by C.H. Oldfather: http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poems/ozymandias, accessed 12 April 2014.

- See section/verse 1.47.4 at the following presentation of the 1933 version of the Loeb Classics translation, which also matches the translation appearing here: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/1C*.html, accessed 12 April 2014.

- For the original Greek, see: Diodorus Siculus. "1.47.4". Bibliotheca Historica (in Greek). Vol. 1–2. Immanel Bekker. Ludwig Dindorf. Friedrich Vogel. In aedibus B. G. Teubneri. At the Perseus Project.

- Desart was "the regularly accepted spelling of the 18th century".[19]

See also

References

- Wells 1990, p. 508.

- Glirastes 1818, p. 24.

- Reprinted in Shelley, Percy Bysshe (1876). Rosalind and Helen – Edited, with notes by H. Buxton Forman, and printed for private distribution. London: Hollinger. p. 72.

- Shelley 1826, p. 100.

- "Ancient Egypt. Statue of Ramesses II, the 'younger Memnon'. The British Museum. Retrieved 12 April 2021".

- British Museum. Colossal bust of Ramesses II, 'The Younger Memnon'. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- Chaney 2006, p. 49.

- Khan 2015, pp. 66, 77.

- Curran.

- Carter 2018.

- Everest & Matthews 2014, p. 307.

- Siculus, Diodorus. Bibliotheca Historica. 1.47.4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Stephens 2009, p. 156.

- "King of Kings". The Economist. 18 December 2013. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- Mozer 2010, p. 728.

- Graham 1925.

- "Romantic Interests: "Ozymandias" and a Runaway Dormouse | The New York Public Library". Nypl.org. 6 July 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe (1819). Rosalind and Helen, a modern eclogue; with other poems. London. p. 92.

- "desert". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Khan 2015, p. 67.

- "MacEachen, Dougald B. CliffsNotes on Shelley's Poems. 18 July 2011". Cliffsnotes.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- Khan 2015, pp. 64, 67, 72.

- Khan 2015, pp. 64, 87.

- Crook & Guiton 1986, p. 99.

- Khan 2015, p. 73.

- Khan 2015, p. 68.

- Cochran 2009, p. 364.

- Khan 2015, pp. 64, 68.

- Khan 2015, p. 69.

- Khan 2015, pp. 69–70.

- Khan 2015, p. 78.

- Khan 2015, pp. 71–72, 88–89.

- Khan 2015, p. 79.

- Mozer 2010.

- "King of Kings". The Economist. 18 December 2013. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- Brown 1998, p. 51.

- Everest 1992, p. 25.

- Rodenbeck 2004, p. 121.

- Stephens 2009, p. 161.

- Ryan, Donald P. (2005). "The Pharaoh and the Poet". Kmt. 16 (4): 76–83. ISSN 1053-0827.

- Bequette, M. K. (1977). "Shelley and Smith: Two Sonnets on Ozymandias". Keats-Shelley Journal. 26: 29–31. ISSN 0453-4387. JSTOR 30212799.

- Pfister 1994, p. 149.

- Regis, Amber K. (2 April 2020). "Interpreting Emily: Ekphrasis and Allusion in Charlotte Brontë's 'Editor's Preface' to Wuthering Heights". Brontë Studies. 45 (2): 168–182. doi:10.1080/14748932.2020.1715052. ISSN 1474-8932. S2CID 216431793.

- Wells, David N. (2013). "Shelley in the Transition to Russian Symbolism: Three Versions of 'Ozymandias'". The Modern Language Review. 108 (4): 1221–1236. doi:10.5699/modelangrevi.108.4.1221. ISSN 0026-7937. JSTOR 10.5699/modelangrevi.108.4.1221.

- Hoffman-Schwartz, Daniel (July 2015). "On Breaking Bad / 'Ozymandias'". Oxford Literary Review. 37 (1): 163–165. doi:10.3366/olr.2015.0157. ISSN 0305-1498.

- Smith, Ben; Robertson, Katie (1 October 2021). "Ozy Media, Once a Darling of Investors, Shuts Down in a Swift Unraveling". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- Kaveney, Roz (2008). Superheroes!: Capes and Crusaders in Comics and Films. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-84511-569-2.

Bibliography

- Khan, Jalal Uddin (2015). "Narrating Shelley's Ozymandias: A Case of the Cultural Hybridity of the Eastern Other". Readings in Oriental Literature: Arabian, Indian, and Islamic. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781443875165.

- Cochran, Peter (2009). "'Another bugbear to you and the world': Byron and Shelley". "Romanticism" – and Byron. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781443808125.

- Crook, Nora; Guiton, Derek (1986). "Elephantiasis". Shelley's Venomed Melody. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521320849.

- Mozer, Hadley J. (2010). "'Ozymandias', or De Casibus Lord Byron: Literary Celebrity on the Rocks". European Romantic Review. 21 (6): 727–749. doi:10.1080/10509585.2010.514494. S2CID 143662539.

- Rodenbeck, John (2004). "Travelers from an Antique Land: Shelley's Inspiration for "Ozymandias"". Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics (24): 121–148. doi:10.2307/4047422. ISSN 1110-8673. JSTOR 4047422.

- Everest, Kelvin; Matthews, Geoffrey (23 June 2014). The Poems of Shelley: Volume Two: 1817–1819. Routledge. ISBN 9781317901075 – via Google Books.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe (1826). "Ozymandias". Miscellaneous and Posthumous Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley. London: W. Benbow.

- Stephens, Walter (2009). "Ozymandias: Or, Writing, Lost Libraries, and Wonder". MLN. 124 (5): S155–S168. ISSN 0026-7910. JSTOR 40606230.

- Chaney, Edward (2006). "Egypt in England and America: The Cultural Memorials of Religion, Royalty and Revolution". In Ascari, Maurizio; Corrado, Adriana (eds.). Sites of Exchange: European Crossroads and Faultlines. Internationale Forschungen zur Allgemeinen und Vergleichenden Literaturwissenschaft. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi. pp. 39–74. ISBN 9042020156.

- Glirastes (1818). Original Poetry. Ozymandias. The Examiner, A Sunday Paper, on politics, domestic economy and theatricals for the year 1818. London: John Hunt. p. 24.

- Carter, Charles (6 July 2018). "Romantic Interests: "Ozymandias" and a Runaway Dormouse". The New York Public Library. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- Graham, Walter (1925). "Shelley's Debt to Leigh Hunt and the Examiner". PMLA. 40 (1): 185–192. doi:10.2307/457275. JSTOR 457275. S2CID 163481698.

- Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. "Ruins of Empire". In Curran, Stuart (ed.). Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (Pennsylvania Electronic ed.).

- Brown, James (January 1998). "'Ozymandias': The Riddle of the Sands". The Keats-Shelley Review. 12 (1): 51–75. doi:10.1179/ksr.1998.12.1.51. ISSN 0952-4142.

- Pfister, Manfred, ed. (1994). Teachable poems from Sting to Shelley (PDF). Heidelberg: C. Winter. ISBN 3-8253-0252-0. OCLC 37456509.

- Wells, John C. (1990). "Ozymandias". Longman pronunciation dictionary. Harrow: Longman. p. 508. ISBN 0-582-05383-8.

Further reading

- Rodenbeck, John (2004). "Travelers from an Antique Land: Shelley's Inspiration for 'Ozymandias'". Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, no. 24 ("Archeology of Literature: Tracing the Old in the New"), 2004, pp. 121–148.

- Johnstone Parr (1957). "Shelley's 'Ozymandias'". Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. VI (1957).

- Waith, Eugene M. (1995). "Ozymandias: Shelley, Horace Smith, and Denon". Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 44, (1995), pp. 22–28.

- Richmond, H. M. (1962). "Ozymandias and the Travelers". Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 11, (Winter, 1962), pp. 65–71.

- Bequette, M. K. (1977). "Shelley and Smith: Two Sonnets on Ozymandias". Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 26, (1977), pp. 29–31.

- Freedman, William (1986). "Postponement and Perspectives in Shelley's 'Ozymandias'". Studies in Romanticism, Vol. 25, No. 1 (Spring, 1986), pp. 63–73.

- Edgecombe, R. S. (2000). "Displaced Christian Images in Shelley's 'Ozymandias'". Keats Shelley Review, 14 (2000), 95–99.

- Sng, Zachary (1998). "The Construction of Lyric Subjectivity in Shelley's 'Ozymandias'". Studies in Romanticism, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Summer, 1998), pp. 217–233.

External links

- Audiorecording of "Ozymandias" by the BBC.

- Ozymandias Summary, Themes, and Analysis

- Ozymandias – Annotated text + analyses aligned to Common Core Standards

Ozymandias public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Ozymandias public domain audiobook at LibriVox- "Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822), "Ozymandias"". Representative Poetry Online. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

(text of poem with notes)

- The poem, set to music