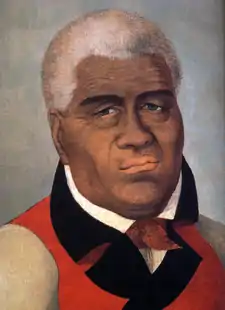

Kamehameha I

Kamehameha I (Hawaiian pronunciation: [kəmehəˈmɛhə]; Kalani Paiʻea Wohi o Kaleikini Kealiʻikui Kamehameha o ʻIolani i Kaiwikapu kauʻi Ka Liholiho Kūnuiākea; c. 1758? – May 8 or 14, 1819), also known as Kamehameha the Great,[1] was the conqueror and first ruler of the Kingdom of Hawaii. The state of Hawaii gave a statue of him to the National Statuary Hall Collection in Washington, D.C. as one of two statues it is entitled to install there.

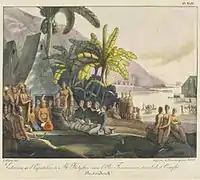

| Kamehameha I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Contemporaneous portrait of Kamehameha | |||||

| King of the Hawaiian Islands | |||||

| Reign | July 1782 – May 8, 1819 | ||||

| Successor | Kamehameha II | ||||

| Born | c. 1758 Kapakai, Kokoiki, Moʻokini Heiau, Kohala, Hawaiʻi Island | ||||

| Died | May 14, 1819 (aged 60-61) Kamakahonu, Kailua-Kona, Kona, Hawaiʻi island | ||||

| Burial | unknown, probably in a hidden location on the island of Hawaiʻi | ||||

| Spouses | (Partial list)

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Kamehameha | ||||

| Father | Keōua | ||||

| Mother | Kekuʻiapoiwa II | ||||

Birth and childhood

Paternity and family history

Kamehameha (known as Paiea at birth),[2] was born to Kekuʻiapoiwa II, the niece of Alapainui, the usurping ruler of Hawaii Island who had killed the two legitimate heirs of Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku during civil war. By most accounts he was born in Ainakea, Kohala, Hawaii.[3] His father was Keōua Kalanikupuapa'ikalaninui;[4][5] however, Native Hawaiian historian Samuel Kamakau says that Maui monarch Kahekili II had hānai adopted (traditional, informal adoption) Kamehameha at birth, as was the custom of the time. Kamakau believes this is why Kahekili II is often referred to as Kamehameha's father.[6] The author also says that Kameʻeiamoku told Kamehameha I that he was the son of Kahekili II, saying, "I have something to tell you: Ka-hekili was your father, you were not Keoua's son. Here are the tokens that you are the son of Ka-hekili."[7]

King Kalakaua wrote that these rumors are scandals and should be dismissed as the offspring of hatred and jealousies of later years.[8] Regardless of the rumors, Kamehameha was a descendant of Keawe through his mother Kekuʻiapoiwa II; Keōua acknowledged him as his son and he is recognized as such by all the sovereigns[9] and most genealogists.[10]

Accounts of Kamehameha I's birth vary, but sources place his birth between 1736 and 1761,[11] with historian Ralph Simpson Kuykendall believing it to be between 1748 and 1761.[12] An early source is thought to imply a 1758 dating because that date matched a visit from Halley's Comet, and would make him close to the age that Francisco de Paula Marín estimated he was.[11] This dating, however, does not accord with the details of many well-known accounts of his life, such as his fighting as a warrior with his uncle, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, or his being of age to father his first children by that time. The 1758 dating also places his birth after the death of his father.[13]

Kamakau published an account in the Ka Nupepa Kuokoa in 1867 placing the date of Kamehameha's birth around 1736.[12] He wrote, "It was during the time of the warfare among the chiefs of [the island of] Hawaii which followed the death of Keawe, chief over the whole island (Ke-awe-i-kekahi-aliʻi-o-ka-moku) that Kamehameha I was born". However, his general dating has been challenged as twenty years too early, related to disputes over Kamakau's inaccuracy of dating compared to accounts of foreign visitors.[14] Regardless, Abraham Fornander wrote in his book, An Account of the Polynesian Race: Its Origins and Migrations: "when Kamehameha died in 1819 he was past eighty years old. His birth would thus fall between 1736 and 1740, probably nearer the former than the latter".[15] A Brief History of the Hawaiian People by William De Witt Alexander lists the birth date in the "Chronological Table of Events of Hawaiian History" as 1736.[16] In 1888 the Kamakau account was challenged by Samuel C. Damon in the missionary publication; The Friend, deferring to a 1753 dating that was the first mentioned by James Jackson Jarves. But the Kamakau dating was widely accepted due to support from Abraham Fornander.[12]

Concealment and childhood

At the time of Kamehameha's birth, Keōua and his half-brother Kalaniʻōpuʻu were serving Alapaʻinui, ruler of the island of Hawaii. Alapaʻinui had brought the brothers to his court after defeating both their fathers in the civil war that followed the death of Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku. Keōua died while Kamehameha was young, so Kamehameha was raised in the court of his uncle, Kalaniʻōpuʻu.[17] The traditional mele chant of Keaka, wife of Alapainui, indicates that Kamehameha was born in the month of ikuwā (winter) or around November.[18] Alapai had given the child, Kamehameha, to his wife, Keaka, and her sister, Hākau, to care for after the ruler discovered the infant had survived.[19][20]

On February 10, 1911, the Kamakau version was challenged by the oral history of the Kaha family, as published in newspaper articles also appearing in the Kuoko. After Kamakau's history was published again, to a larger English reading public in 1911 Hawaii, the Kaha version of these events was published by Kamaka Stillman, who had objected to the Nupepa article.[21]

Unification of the islands

Hawaii Island

Kamehameha was raised in the royal court of his uncle Kalaniʻōpuʻu. He achieved prominence in 1782, upon Kalaniʻōpuʻu's death. While the kingship was inherited by Kīwalaʻō, Kalaniʻōpuʻu's son, Kamehameha was given a prominent religious position as guardian of the Hawaiian god of war, Kūkāʻilimoku. He was also given control of the district of Waipiʻo Valley. The two cousins' relationship was strained after Kamehameha made a dedication to the gods instead of allowing Kīwalaʻō to do that. Kamehameha accepted the allegiance of a group of chiefs from the Kona district.

The other story took place after the prophecy was passed along by the high priests and high chiefs. When Kamehameha was able to lift the Naha Stone, he was considered the fulfiller of the prophecy. Other ruling chiefs, Keawe Mauhili, the Mahoe (twins) Keoua, and other chiefs rejected the prophecy of Ka Poukahi. The high chiefs of Kauai supported Kiwala`o even after learning about the prophecy.

The five Kona chiefs supporting Kamehameha were Keʻeaumoku Pāpaʻiahiahi (Kamehameha's father-in-law/grand uncle), Keaweaheulu Kaluaʻāpana (Kamehameha's uncle), Kekūhaupiʻo (Kamehameha's warrior teacher), and Kameʻeiamoku and Kamanawa (twin uncles of Kamehameha). They defended Kamehameha as the unifier Ka Na`i aupuni. High Chiefs Keawe Mauhili and Keeaumoku were by genealogy the next in line for ali`i nui. Both chose the younger nephews Kīwalaʻō and Kamehameha over themselves. Kīwalaʻō was soon defeated in the first key conflict, the Battle of Mokuʻōhai. Kamehameha and his chiefs took over Konohiki responsibilities and sacred obligations of the districts of Kohala, Kona, and Hāmākua on Hawaiʻi island.[22]

The prophecy included far more than Hawaiʻi island. It went across and beyond the Pacific Islands to the semi-continent of Aotearoa (New Zealand). He was supported by his most political wife Kaʻahumanu and father, High Chief Keeaumoku. Senior counselor to Kamehameha, she became one of Hawaiʻi's most powerful figures. Kamehameha and his council of chiefs planned to unite the rest of the Hawaiian Islands. Allies came from British and American traders, who sold guns and ammunition to Kamehameha. Another major factor in Kamehameha's continued success was the support of Kauai chief Ka`iana and Captain Brown, who used to be with Kaeo okalani. He guaranteed Kamehameha unlimited gunpowder from China and gave him the formula for gunpowder: sulfur, saltpeter, and charcoal, all of which are abundant in the islands. Two westerners who lived on Hawaiʻi island, Isaac Davis and John Young, married native Hawaiian women and assisted Kamehameha.[23]

Olowalu Massacre

In 1789, Simon Metcalfe captained the fur trading vessel the Eleanora while his son, Thomas Humphrey Metcalfe, captained the ship Fair American along the Northwest Coast. They were to rendezvous in what was then known as the Sandwich Islands. Fair American was held up when it was captured by the Spanish and then quickly released in San Blas. The Eleanora arrived in 1790, where it was greeted by chief Kameʻeiamoku. The chief did something that the captain took offense to, and Metcalfe struck the chief with a rope's end. Sometime later, while docked in Honuaula, Maui, a small boat tied to the ship was stolen by native townspeople with a crewman inside. When Metcalfe discovered where the boat was taken, he sailed directly to the village of Olowalu. There he confirmed the boat had been broken apart and the man killed. He had already fired muskets into the previous village where he was anchored, killing some residents. Metcalfe now took aim at Olowalu. He had all cannons moved to one side of the ship and began his trading call out to the locals. Hundreds of people came out to the beach to trade and canoes were launched. When they were within firing range, the ship fired on the Hawaiians, killing over 100. Six weeks later, Fair American was stuck near the Kona coast of Hawaii where chief Kameʻeiamoku was living, near Kaʻūpūlehu. He had decided to attack the next foreign ship to avenge the strike by the elder Metcalfe. He canoed out to the ship with his men, where he killed Metcalfe's son and all but one (Isaac Davis) of the five crewmen. Kamehameha took Davis into protection and took possession of the ship. Eleanora was at that time anchored at Kealakekua Bay, where the ship's boatswain had gone ashore and been captured by Kamehameha's forces because Kamehameha believed Metcalfe was planning more revenge. Eleanora waited several days before sailing off, apparently without knowledge of what had happened to Fair American or Metcalfe's son. Davis and Eleanora's boatswain, John Young, tried to escape, but were treated as chiefs, given wives and settled in Hawaii.[24]

Invasion of Maui

In 1790 Kamehameha's army invaded Maui with the assistance of John Young and Isaac Davis. Using cannons from the Fair American, they defeated Maui's army at the bloody Battle of Kepaniwai while the aliʻi Kahekili II was on Oahu.[25]

Death of Keōua Kuahuula

In 1790 Kamehameha advanced against the district of Puna deposing Chief Keawemaʻuhili. At his home in Kaʻū, where he was exiled, Keōua Kūʻahuʻula took advantage of Kamehameha's absence in Maui and began an uprising. When Kamehameha returned, Keōua escaped to the Kīlauea volcano, which erupted. Many warriors died from the poisonous gas emitted from the volcano.[25]

When the Puʻukoholā Heiau was completed in 1791, Kamehameha invited Keōua to meet with him. Keōua may have been dispirited by his recent losses. He may have mutilated himself before landing so as to render himself an inappropriate sacrificial victim. As he stepped on shore, one of Kamehameha's chiefs threw a spear at him. By some accounts, he dodged it but was then cut down by musket fire. Caught by surprise, Keōua's bodyguards were killed. With Keōua dead, and his supporters captured or slain, Kamehameha became King of Hawaiʻi island.[26]

Maui and Oʻahu

In 1795, Kamehameha set sail with an armada of 960 war canoes and 10,000 soldiers. He quickly secured the lightly defended islands of Maui and Molokaʻi at the Battle of Kawela. He moved on to the island of Oʻahu, landing his troops at Waiʻalae and Waikīkī. Kamehameha did not know that one of his commanders, a high-ranking aliʻi named Kaʻiana, had defected to Kalanikūpule. Kaʻiana assisted in cutting notches into the Nuʻuanu Pali mountain ridge; these notches, like those on a castle turret, were to serve as gunports for Kalanikūpule's cannon.[27] In a series of skirmishes, Kamehameha's forces pushed Kalanikūpule's men back until they were cornered on the Pali Lookout. While Kamehameha moved on the Pali, his troops took heavy fire from the cannon. He assigned two divisions of his best warriors to climb to the Pali to attack the cannons from behind; they surprised Kalanikūpule's gunners and took control. With the loss of their guns, Kalanikūpule's troops fell into disarray and were cornered by Kamehameha's still-organized troops. A fierce battle at Nuʻuanu ensued, with Kamehameha's forces forming an enclosing wall. Using traditional Hawaiian spears, as well as muskets and cannon, they killed most of Kalanikūpule's forces. Over 400 men were forced over the Pali's cliff, a drop of 1,000 feet. Kaʻiana was killed during the action; Kalanikūpule was later captured and sacrificed to Kūkāʻilimoku.[28]

In April 1810, Kamehameha I negotiated the peaceful unification of the islands with Kauaʻi. His court genealogist and high priest Kalaikuʻahulu was instrumental in the monarch's decision not to kill Kaumualiʻi, the ruler of that island, when he was the single member of the aliʻi council to agree with Kamehameha's own reluctance to do so.[29] The other aliʻi continued with the plan to poison Kaumualiʻi when Isaac Davis warned him, making the ruler cut his trip short and return to Kauaʻi, leaving Davis to be poisoned by the aliʻi instead.[30]

Aliʻi nui of the Hawaiian Islands

As ruler, Kamehameha took steps to ensure the islands remained a united realm after his death. He unified the legal system. He used the products collected in taxes to promote trade with Europe and the United States.

The origins of the Law of the Splintered Paddle are derived from before the unification of the Island of Hawaiʻi. In 1782 during a raid, Kamehameha caught his foot in a rock. Two local fishermen, fearful of the great warrior, hit Kamehameha hard on the head with a large paddle, which broke the paddle. Kamehameha was stunned and left for dead, allowing the fisherman and his companion to escape. Twelve years later, the same fishermen were brought before Kamehameha for punishment. The king instead blamed himself for attacking innocent people, gave the fishermen gifts of land and set them free. He declared the new law, "Let every elderly person, woman, and child lie by the roadside in safety."[31]

Young and Davis became advisors to Kamehameha and provided him with advanced weapons that helped in combat. Kamehameha was also a religious king and the holder of the war god Kukaʻ ilimoku. The explorer George Vancouver noted that Kamehameha worshiped his gods and wooden images in a heiau, but originally wanted to bring England's religion, Christianity, to Hawaiʻi. Missionaries were not sent from Great Britain because Kamehameha told Vancouver that the gods he worshiped were his gods with mana, and that through these gods, Kamehameha had become supreme ruler over all of the islands. Witnessing Kamehameha's devotion, Vancouver decided against sending missionaries from England.[32]

Later life

After about 1812, Kamehameha spent his time at Kamakahonu, a compound he built in Kailua-Kona.[33] As was the custom of the time, he had several wives and many children, though he outlived about half of them.

Final resting place

When Kamehameha died on May 8 or 14, 1819,[34][35][36] his body was hidden by his trusted friends, Hoapili and Hoʻolulu, in the ancient custom called hūnākele (literally, "to hide in secret"). The mana, or power of a person, was considered to be sacred. As per the ancient custom, his body was buried in a hidden location because of his mana. His final resting place remains unknown. At one point in his reign, Kamehameha III asked that Hoapili show him where his father's bones were buried, but on the way there Hoapili knew that they were being followed, so he turned around.[37]

Family

Kamehameha had many wives. The exact number is debated because documents that recorded the names of his wives were destroyed. Bingham lists 21, but earlier research from Mary Kawena Pukui counted 26.[38] In Kamehameha's Children Today authors Ahlo, Johnson and Walker list 30 wives: 18 who bore children, and 12 who did not. They state the total number of children to be 35: 17 sons and 18 daughters.[39] While he had many wives and children, his children through his highest-ranking wife, Keōpūolani, succeeded him to the throne.[40] In Ho`omana: Understanding the Sacred and Spiritual, Chun stated that Keōpūolani supported Kaʻahumanu's ending of the Kapu system as the best way to ensure that Kamehameha's children and grandchildren would rule the kingdom.[41]

|

Family tree based on Abraham Fornander's "An Account of the Polynesian Race" and other works from the author, Queen Liliuokalani's "Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen", Samuel Mānaiakalani Kamakau's "Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii" and other works by the author, John Papa ʻĪʻī's "Fragments of Hawaiian History", Edith Kawelohea McKinzie's "Hawaiian Genealogies: Extracted from Hawaiian Language Newspapers, Vol. I & II", Kanalu G. Terry Young's "Rethinking the Native Hawaiian Past", Charles Ahlo, Jerry Walker, and Rubellite Kawena Johnson's "Kamehameha's Children Today", The Hawaiian Historical Society Reports, the genealogies of the Hawaiian Royal families in Kingdom of Hawaii probate, the works of Sheldon Dibble and David Malo as well as the Hawaii State Archive genealogy books.

|

Citations

- A 19th-century Italian biographer calls him King Tammeamea and his son Rio-Rio (Kamehameha II).Dizionario biografico universale, Volume 5, by Felice Scifoni, Publisher Davide Passagli, Florence (1849); page 249.

- Noles, Jim (2009). "50". A Pocketful of History: Four Hundred Years of America.

- Alexander 1912, p. 7.

- Liliʻuokalani & Forbes 2013, p. 3.

- Pratt 1920, p. 9.

- Kamakau 1992, p. 68.

- Kamakau 1992, p. 188.

- Hawaii), David Kalakaua (King of (1888). The Legends and Myths of Hawaii: The Fables and Folk-lore of a Strange People. C.L. Webster. p. 386.

- "Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen". digital.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- Dibble 1843, p. 54.

- Morrison 2003, p. 67.

- Kuykendall 1965, p. 429.

- Tregaskis 1973, p. xxi.

- Kamakau 1992, p. 66.

- Fornander & Stokes 1880, p. 136.

- Alexander 1912, p. 331.

- Kanahele 1986, p. 10.

- TRUSTEES 1937, p. 15.

- ʻĪʻī 1983, p. 4.

- Taylor 1922, p. 79.

- Alexander 1912, pp. 6–8.

- Desha & Frazier 2000, pp. 1–138.

- Archer 2018, p. 78.

- Kuykendall 1965, p. 24.

- "Kamehameha the Great". National Park Service.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Gowen 1919, p. 207-208, 210.

- "Pali notches". Outdoor Project. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Gowen 1919, p. 250.

- ʻĪʻī 1983, p. 81.

- ʻĪʻī 1983, p. 83.

- The Law of the Splintered Paddle: Kānāwai Māmalahoe. (PDF). hawaii.edu

- Kamakau 1992, pp. 180–181.

- Gowen 1919, p. 306.

- Mookini 1998, pp. 1–24.

- Gast 1973, p. 24.

- Klieger 1998, p. 24.

- Potter, Kasdon & Rayson 2003, p. 35.

- Van Dyke 2008, p. 360.

- Ahlo, Walker & Johnson 2000, pp. 2–80.

- Vowell 2011, p. 32.

- Chun 2007, p. 13.

References

- Ahlo, Charles; Walker, Jerry; Johnson, Rubellite Kawena Kenney (2000). Kamehameha's Children Today. Native Books Inc. ISBN 9780996780308. OCLC 950432478.

- Alexander, W.D. (1912). "Birth of Kamehameha I". Annual Report of the Hawaiian Historical Society. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. ASIN B01N6XLV7T. hdl:10524/11853.

- Archer, Seth (2018). Sharks upon the Land: Colonialism, Indigenous Health, and Culture in Hawai'i, 1778–1855. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-80064-5. OCLC 1037875231.

- Choris, Louis (1822). Voyage pittoresque autour du monde. Paris : F. Didot. ISBN 9780665171024. OCLC 11888260.

- Chun, Malcolm Naea (2007). Ho'omana: Understanding the Sacred and Spiritual. Curriculum Research & Development Group, University of Hawaii. ISBN 978-1-58351-047-6.

- Desha, Stephen; Frazier, Frances N. (2000). Kamehameha and His Warrior Kekūhaupiʻo. Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 978-0873360562. OCLC 44114603.

- Dibble, Sheldon (1843), History of the Sandwich Islands, Honolulu: Press of the Mission Siminary, ASIN B06XWQZFY3, OCLC 616786480

- Fornander, Abraham; Stokes, John F.G. (1880). An Account of the Polynesian Race: Its Origins and Migrations, and the Ancient History of the Hawaiian people up to the time of Kamehameha I. Vol. II. Trubner And Co., Ludgate Hill. ISBN 978-1-330-05721-6. OCLC 4888555.

- Gowen, Herbert Henry (1919). The Napoleon of the Pacific: Kamehameha the Great. Fleming H. Revell Company . ISBN 978-1371128616.

- Gast, Ross H. (1973). Don Francisco De Paula Marin: The Letters and Journals of Francisco De Paula Marin. Hawaiian Historical Society. ISBN 978-0824802202. OCLC 477674224.

- ʻĪʻī, John Papa (1983). Fragments of Hawaiian History (2 ed.). Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-910240-31-4. OCLC 6849173.

- Kamakau, Samuel (1992) [1961]. Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii (Revised ed.). Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 0-87336-014-1.

- Kanahele, George H. (1986), Pauahi: The Kamehameha Legacy, Kalihi: Kamehameha Schools Press, ISBN 978-0873360050

- Klieger, P. Christiaan (1998). Moku'ula: Maui's sacred island. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 1-58178-002-8.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1965), The Hawaiian Kingdom, 1778–1854, Foundation and Transformation, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0870224317, OCLC 47008868

- Liliʻuokalani, Queen; Forbes, David W. (2013). Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen Liliʻuokalani (annotated ed.). Hui Hānai. ISBN 9780988727823. OCLC 869268731.

- Morrison, Susan (2003). Kamehameha: The Warrior King of Hawai'i. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824827007.

- Mookini, Esther T. (1998). "Keopuolani: Sacred Wife, Queen Mother, 1778–1823" (PDF). The Hawaiian Journal of History. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. 32. ASIN B002T9NQT2. hdl:10524/569.

- Potter, Norris Whitfield; Kasdon, Lawrence M.; Rayson, Ann (2003). History of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Bess Press. ISBN 978-1-57306-150-6. OCLC 131810736.

- Pratt, Elizabeth Kekaaniauokalani Kalaninuiohilaukapu (1920). History of Keoua Kalanikupuapa-i-nui: Father of Hawaii Kings, and His Descendants, with Notes on Kamehameha I, First King of All Hawaii. T. H. OCLC 616786469.

- Taylor, Albert Pierce (1922). Under Hawaiian Skies. Advertiser Pub. Co. ISBN 9781296352646. OCLC 479709.

- Tregaskis, Richard (1973). The warrior king: Hawaii's Kamehameha the Great. Macmillan. ISBN 9780026198509. OCLC 745361.

- TRUSTEES, Hue-M. (1937). "APPENDIX B REPORT TO THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY BY ITS TRUSTEES CONCERNING THE BIRTH DATE OF KAMEHAMEHA I AND KAMEHAMEHA DAY CELEBRATIONS". Annual Report of the Hawaiian Historical Society. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. hdl:10524/69.

- Van Dyke, Jon M. (2008). Who Owns the Crown Lands of Hawaii?. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824832117. OCLC 263706655.

- Vowell, Sarah (2011). Unfamiliar Fishes. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-48645-0. OCLC 865337344.

Further reading

- Levathes, Louise E. (November 1983). "Kamehameha – Hawaii's Warrior King". National Geographic. Vol. 164, no. 5. pp. 558–599. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.