Castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars debate the scope of the word castle, but usually consider it to be the private fortified residence of a lord or noble. This is distinct from a palace, which is not fortified; from a fortress, which was not always a residence for royalty or nobility; from a pleasance which was a walled-in residence for nobility, but not adequately fortified;[lower-alpha 1] and from a fortified settlement, which was a public defence – though there are many similarities among these types of construction. Use of the term has varied over time and has been applied to structures as diverse as hill forts and country houses. Over the approximately 900 years that castles were built, they took on a great many forms with many different features, although some, such as curtain walls, arrowslits, and portcullises, were commonplace.

European-style castles originated in the 9th and 10th centuries, after the fall of the Carolingian Empire resulted in its territory being divided among individual lords and princes. These nobles built castles to control the area immediately surrounding them and the castles were both offensive and defensive structures; they provided a base from which raids could be launched as well as offered protection from enemies. Although their military origins are often emphasised in castle studies, the structures also served as centres of administration and symbols of power. Urban castles were used to control the local populace and important travel routes, and rural castles were often situated near features that were integral to life in the community, such as mills, fertile land, or a water source.

Many northern European castles were originally built from earth and timber, but had their defences replaced later by stone. Early castles often exploited natural defences, lacking features such as towers and arrowslits and relying on a central keep. In the late 12th and early 13th centuries, a scientific approach to castle defence emerged. This led to the proliferation of towers, with an emphasis on flanking fire. Many new castles were polygonal or relied on concentric defence – several stages of defence within each other that could all function at the same time to maximise the castle's firepower. These changes in defence have been attributed to a mixture of castle technology from the Crusades, such as concentric fortification, and inspiration from earlier defences, such as Roman forts. Not all the elements of castle architecture were military in nature, so that devices such as moats evolved from their original purpose of defence into symbols of power. Some grand castles had long winding approaches intended to impress and dominate their landscape.

Although gunpowder was introduced to Europe in the 14th century, it did not significantly affect castle building until the 15th century, when artillery became powerful enough to break through stone walls. While castles continued to be built well into the 16th century, new techniques to deal with improved cannon fire made them uncomfortable and undesirable places to live. As a result, true castles went into decline and were replaced by artillery forts with no role in civil administration, and country houses that were indefensible. From the 18th century onwards, there was a renewed interest in castles with the construction of mock castles, part of a romantic revival of Gothic architecture, but they had no military purpose.

Definition

Etymology

The word castle is derived from the Latin word castellum, which is a diminutive of the word castrum, meaning "fortified place". The Old English castel, Occitan castel or chastel, French château, Spanish castillo, Portuguese castelo, Italian castello, and a number of words in other languages also derive from castellum.[2] The word castle was introduced into English shortly before the Norman Conquest to denote this type of building, which was then new to England.[3]

Defining characteristics

In its simplest terms, the definition of a castle accepted amongst academics is "a private fortified residence".[4] This contrasts with earlier fortifications, such as Anglo-Saxon burhs and walled cities such as Constantinople and Antioch in the Middle East; castles were not communal defences but were built and owned by the local feudal lords, either for themselves or for their monarch.[5] Feudalism was the link between a lord and his vassal where, in return for military service and the expectation of loyalty, the lord would grant the vassal land.[6] In the late 20th century, there was a trend to refine the definition of a castle by including the criterion of feudal ownership, thus tying castles to the medieval period; however, this does not necessarily reflect the terminology used in the medieval period. During the First Crusade (1096–1099), the Frankish armies encountered walled settlements and forts that they indiscriminately referred to as castles, but which would not be considered as such under the modern definition.[4]

Castles served a range of purposes, the most important of which were military, administrative, and domestic. As well as defensive structures, castles were also offensive tools which could be used as a base of operations in enemy territory. Castles were established by Norman invaders of England for both defensive purposes and to pacify the country's inhabitants.[7] As William the Conqueror advanced through England, he fortified key positions to secure the land he had taken. Between 1066 and 1087, he established 36 castles such as Warwick Castle, which he used to guard against rebellion in the English Midlands.[8][9]

Towards the end of the Middle Ages, castles tended to lose their military significance due to the advent of powerful cannons and permanent artillery fortifications;[10] as a result, castles became more important as residences and statements of power.[11] A castle could act as a stronghold and prison but was also a place where a knight or lord could entertain his peers.[12] Over time the aesthetics of the design became more important, as the castle's appearance and size began to reflect the prestige and power of its occupant. Comfortable homes were often fashioned within their fortified walls. Although castles still provided protection from low levels of violence in later periods, eventually they were succeeded by country houses as high status residences.[13]

Terminology

Castle is sometimes used as a catch-all term for all kinds of fortifications and, as a result, has been misapplied in the technical sense. An example of this is Maiden Castle which, despite the name, is an Iron Age hill fort which had a very different origin and purpose.[14]

Although "castle" has not become a generic term for a manor house (like château in French and Schloss in German), many manor houses contain "castle" in their name while having few if any of the architectural characteristics, usually as their owners liked to maintain a link to the past and felt the term "castle" was a masculine expression of their power.[15] In scholarship the castle, as defined above, is generally accepted as a coherent concept, originating in Europe and later spreading to parts of the Middle East, where they were introduced by European Crusaders. This coherent group shared a common origin, dealt with a particular mode of warfare, and exchanged influences.[16]

In different areas of the world, analogous structures shared features of fortification and other defining characteristics associated with the concept of a castle, though they originated in different periods and circumstances and experienced differing evolutions and influences. For example, shiro in Japan, described as castles by historian Stephen Turnbull, underwent "a completely different developmental history, were built in a completely different way and were designed to withstand attacks of a completely different nature".[17] While European castles built from the late 12th and early 13th century onwards were generally stone, shiro were predominantly timber buildings into the 16th century.[18]

By the 16th century, when Japanese and European cultures met, fortification in Europe had moved beyond castles and relied on innovations such as the Italian trace italienne and star forts.[17] Forts in India present a similar case; when they were encountered by the British in the 17th century, castles in Europe had generally fallen out of use militarily. Like shiro, the Indian forts, durga or durg in Sanskrit, shared features with castles in Europe such as acting as a domicile for a lord as well as being fortifications. They too developed differently from the structures known as castles that had their origins in Europe.[19]

Common features

Motte

A motte was an earthen mound with a flat top. It was often artificial, although sometimes it incorporated a pre-existing feature of the landscape. The excavation of earth to make the mound left a ditch around the motte, called a moat (which could be either wet or dry). Although the motte is commonly associated with the bailey to form a motte-and-bailey castle, this was not always the case and there are instances where a motte existed on its own.[20]

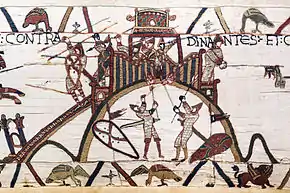

"Motte" refers to the mound alone, but it was often surmounted by a fortified structure, such as a keep, and the flat top would be surrounded by a palisade.[20] It was common for the motte to be reached over a flying bridge (a bridge over the ditch from the counterscarp of the ditch to the edge of the top of the mound), as shown in the Bayeux Tapestry's depiction of Château de Dinan.[21] Sometimes a motte covered an older castle or hall, whose rooms became underground storage areas and prisons beneath a new keep.[22]

Bailey and enceinte

A bailey, also called a ward, was a fortified enclosure. It was a common feature of castles, and most had at least one. The keep on top of the motte was the domicile of the lord in charge of the castle and a bastion of last defence, while the bailey was the home of the rest of the lord's household and gave them protection. The barracks for the garrison, stables, workshops, and storage facilities were often found in the bailey. Water was supplied by a well or cistern. Over time the focus of high status accommodation shifted from the keep to the bailey; this resulted in the creation of another bailey that separated the high status buildings – such as the lord's chambers and the chapel – from the everyday structures such as the workshops and barracks.[23]

From the late 12th century there was a trend for knights to move out of the small houses they had previously occupied within the bailey to live in fortified houses in the countryside.[24] Although often associated with the motte-and-bailey type of castle, baileys could also be found as independent defensive structures. These simple fortifications were called ringworks.[25] The enceinte was the castle's main defensive enclosure, and the terms "bailey" and "enceinte" are linked. A castle could have several baileys but only one enceinte. Castles with no keep, which relied on their outer defences for protection, are sometimes called enceinte castles;[26] these were the earliest form of castles, before the keep was introduced in the 10th century.[27]

Keep

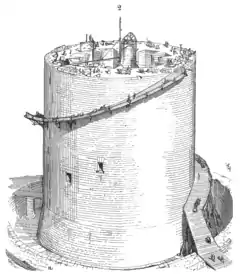

A keep was a great tower and usually the most strongly defended point of a castle before the introduction of concentric defence. "Keep" was not a term used in the medieval period – the term was applied from the 16th century onwards – instead "donjon" was used to refer to great towers,[28] or turris in Latin. In motte-and-bailey castles, the keep was on top of the motte.[20] "Dungeon" is a corrupted form of "donjon" and means a dark, unwelcoming prison.[29] Although often the strongest part of a castle and a last place of refuge if the outer defences fell, the keep was not left empty in case of attack but was used as a residence by the lord who owned the castle, or his guests or representatives.[30]

At first this was usual only in England, when after the Norman Conquest of 1066 the "conquerors lived for a long time in a constant state of alert";[31] elsewhere the lord's wife presided over a separate residence (domus, aula or mansio in Latin) close to the keep, and the donjon was a barracks and headquarters. Gradually, the two functions merged into the same building, and the highest residential storeys had large windows; as a result for many structures, it is difficult to find an appropriate term.[32] The massive internal spaces seen in many surviving donjons can be misleading; they would have been divided into several rooms by light partitions, as in a modern office building. Even in some large castles the great hall was separated only by a partition from the lord's "chamber", his bedroom and to some extent his office.[33]

Curtain wall

Curtain walls were defensive walls enclosing a bailey. They had to be high enough to make scaling the walls with ladders difficult and thick enough to withstand bombardment from siege engines which, from the 15th century onwards, included gunpowder artillery. A typical wall could be 3 m (10 ft) thick and 12 m (39 ft) tall, although sizes varied greatly between castles. To protect them from undermining, curtain walls were sometimes given a stone skirt around their bases. Walkways along the tops of the curtain walls allowed defenders to rain missiles on enemies below, and battlements gave them further protection. Curtain walls were studded with towers to allow enfilading fire along the wall.[34] Arrowslits in the walls did not become common in Europe until the 13th century, for fear that they might compromise the wall's strength.[35]

Gatehouse

The entrance was often the weakest part in a circuit of defences. To overcome this, the gatehouse was developed, allowing those inside the castle to control the flow of traffic. In earth and timber castles, the gateway was usually the first feature to be rebuilt in stone. The front of the gateway was a blind spot and to overcome this, projecting towers were added on each side of the gate in a style similar to that developed by the Romans.[36] The gatehouse contained a series of defences to make a direct assault more difficult than battering down a simple gate. Typically, there were one or more portcullises – a wooden grille reinforced with metal to block a passage – and arrowslits to allow defenders to harry the enemy. The passage through the gatehouse was lengthened to increase the amount of time an assailant had to spend under fire in a confined space and unable to retaliate.[37]

It is a popular myth that so-called murder holes – openings in the ceiling of the gateway passage – were used to pour boiling oil or molten lead on attackers; the price of oil and lead and the distance of the gatehouse from fires meant that this was impractical.[38] This method was, however, a common practice in the MENA region and the Mediterranean castles and fortifications where such resources were abundant.[39][40] They were most likely used to drop objects on attackers, or to allow water to be poured on fires to extinguish them.[38] Provision was made in the upper storey of the gatehouse for accommodation so the gate was never left undefended, although this arrangement later evolved to become more comfortable at the expense of defence.[41]

During the 13th and 14th centuries the barbican was developed.[42] This consisted of a rampart, ditch, and possibly a tower, in front of the gatehouse[43] which could be used to further protect the entrance. The purpose of a barbican was not just to provide another line of defence but also to dictate the only approach to the gate.[44]

Moat

A moat was a ditch surrounding a castle – or dividing one part of a castle from another – and could be either dry or filled with water. Its purpose often had a defensive purpose, preventing siege towers from reaching walls making mining harder, but could also be ornamental.[45][46][47] Water moats were found in low-lying areas and were usually crossed by a drawbridge, although these were often replaced by stone bridges.[45] The site of the 13th-century Caerphilly Castle in Wales covers over 30 acres (12 ha) and the water defences, created by flooding the valley to the south of the castle, are some of the largest in Western Europe.[48]

Battlements

Battlements were most often found surmounting curtain walls and the tops of gatehouses, and comprised several elements: crenellations, hoardings, machicolations, and loopholes. Crenellation is the collective name for alternating crenels and merlons: gaps and solid blocks on top of a wall. Hoardings were wooden constructs that projected beyond the wall, allowing defenders to shoot at, or drop objects on, attackers at the base of the wall without having to lean perilously over the crenellations, thereby exposing themselves to retaliatory fire. Machicolations were stone projections on top of a wall with openings that allowed objects to be dropped on an enemy at the base of the wall in a similar fashion to hoardings.[49]

Arrowslits

Arrowslits, also commonly called loopholes, were narrow vertical openings in defensive walls which allowed arrows or crossbow bolts to be fired on attackers. The narrow slits were intended to protect the defender by providing a very small target, but the size of the opening could also impede the defender if it was too small. A smaller horizontal opening could be added to give an archer a better view for aiming.[50] Sometimes a sally port was included; this could allow the garrison to leave the castle and engage besieging forces.[51] It was usual for the latrines to empty down the external walls of a castle and into the surrounding ditch.[52]

Postern

A postern is a secondary door or gate in a concealed location, usually in a fortification such as a city wall.[53]

Great hall

The great hall was a large, decorated room where a lord received his guests. The hall represented the prestige, authority, and richness of the lord. Events such as feasts, banquets, social or ceremonial gatherings, meetings of the military council, and judicial trials were held in the great hall. Sometimes the great hall existed as a separate building, in that case, it was called a hall-house.[54]

History

Antecedents

Historian Charles Coulson states that the accumulation of wealth and resources, such as food, led to the need for defensive structures. The earliest fortifications originated in the Fertile Crescent, the Indus Valley, Europe, Egypt, and China where settlements were protected by large walls. In Northern Europe hill forts were first developed in the Bronze Age, which then proliferated across Europe in the Iron Age. Hillforts in Britain typically used earthworks rather than stone as a building material.[58] Many earthworks survive today, along with evidence of palisades to accompany the ditches. In central and western Europe, oppida emerged in the 2nd century BC; these were densely inhabited fortified settlements, such as the oppidum of Manching.[59] Some oppida walls were built on a massive scale, utilising stone, wood, iron and earth in their construction.[60][61] The Romans encountered fortified settlements such as hill forts and oppida when expanding their territory into northern Europe.[59] Their defences were often effective, and were only overcome by the extensive use of siege engines and other siege warfare techniques, such as at the Battle of Alesia. The Romans' own fortifications (castra) varied from simple temporary earthworks thrown up by armies on the move, to elaborate permanent stone constructions, notably the milecastles of Hadrian's Wall. Roman forts were generally rectangular with rounded corners – a "playing-card shape".[62]

In the medieval period, castles were influenced by earlier forms of elite architecture, contributing to regional variations. Importantly, while castles had military aspects, they contained a recognisable household structure within their walls, reflecting the multi-functional use of these buildings.[63]

Origins (9th and 10th centuries)

The subject of the emergence of castles in Europe is a complex matter which has led to considerable debate. Discussions have typically attributed the rise of the castle to a reaction to attacks by Magyars, Muslims, and Vikings and a need for private defence.[64] The breakdown of the Carolingian Empire led to the privatisation of government, and local lords assumed responsibility for the economy and justice.[65] However, while castles proliferated in the 9th and 10th centuries the link between periods of insecurity and building fortifications is not always straightforward. Some high concentrations of castles occur in secure places, while some border regions had relatively few castles.[66]

It is likely that the castle evolved from the practice of fortifying a lordly home. The greatest threat to a lord's home or hall was fire as it was usually a wooden structure. To protect against this, and keep other threats at bay, there were several courses of action available: create encircling earthworks to keep an enemy at a distance; build the hall in stone; or raise it up on an artificial mound, known as a motte, to present an obstacle to attackers.[67] While the concept of ditches, ramparts, and stone walls as defensive measures is ancient, raising a motte is a medieval innovation.[68]

A bank and ditch enclosure was a simple form of defence, and when found without an associated motte is called a ringwork; when the site was in use for a prolonged period, it was sometimes replaced by a more complex structure or enhanced by the addition of a stone curtain wall.[69] Building the hall in stone did not necessarily make it immune to fire as it still had windows and a wooden door. This led to the elevation of windows to the second storey – to make it harder to throw objects in – and to move the entrance from ground level to the second storey. These features are seen in many surviving castle keeps, which were the more sophisticated version of halls.[70] Castles were not just defensive sites but also enhanced a lord's control over his lands. They allowed the garrison to control the surrounding area,[71] and formed a centre of administration, providing the lord with a place to hold court.[72]

Building a castle sometimes required the permission of the king or other high authority. In 864 the King of West Francia, Charles the Bald, prohibited the construction of castella without his permission and ordered them all to be destroyed. This is perhaps the earliest reference to castles, though military historian R. Allen Brown points out that the word castella may have applied to any fortification at the time.[73]

In some countries the monarch had little control over lords, or required the construction of new castles to aid in securing the land so was unconcerned about granting permission – as was the case in England in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest and the Holy Land during the Crusades. Switzerland is an extreme case of there being no state control over who built castles, and as a result there were 4,000 in the country.[74] There are very few castles dated with certainty from the mid-9th century. Converted into a donjon around 950, Château de Doué-la-Fontaine in France is the oldest standing castle in Europe.[75]

11th century

From 1000 onwards, references to castles in texts such as charters increased greatly. Historians have interpreted this as evidence of a sudden increase in the number of castles in Europe around this time; this has been supported by archaeological investigation which has dated the construction of castle sites through the examination of ceramics.[76] The increase in Italy began in the 950s, with numbers of castles increasing by a factor of three to five every 50 years, whereas in other parts of Europe such as France and Spain the growth was slower. In 950 Provence was home to 12 castles, by 1000 this figure had risen to 30, and by 1030 it was over 100.[77] Although the increase was slower in Spain, the 1020s saw a particular growth in the number of castles in the region, particularly in contested border areas between Christian and Muslim lands.[78]

Despite the common period in which castles rose to prominence in Europe, their form and design varied from region to region. In the early 11th century, the motte and keep – an artificial mound with a palisade and tower on top – was the most common form of castle in Europe, everywhere except Scandinavia.[77] While Britain, France, and Italy shared a tradition of timber construction that was continued in castle architecture, Spain more commonly used stone or mud-brick as the main building material.[79]

The Muslim invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in the 8th century introduced a style of building developed in North Africa reliant on tapial, pebbles in cement, where timber was in short supply.[80] Although stone construction would later become common elsewhere, from the 11th century onwards it was the primary building material for Christian castles in Spain,[81] while at the same time timber was still the dominant building material in north-west Europe.[78]

Historians have interpreted the widespread presence of castles across Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries as evidence that warfare was common, and usually between local lords.[83] Castles were introduced into England shortly before the Norman Conquest in 1066.[84] Before the 12th century castles were as uncommon in Denmark as they had been in England before the Norman Conquest. The introduction of castles to Denmark was a reaction to attacks from Wendish pirates, and they were usually intended as coastal defences.[74] The motte and bailey remained the dominant form of castle in England, Wales, and Ireland well into the 12th century.[85] At the same time, castle architecture in mainland Europe became more sophisticated.[86]

The donjon[87] was at the centre of this change in castle architecture in the 12th century. Central towers proliferated, and typically had a square plan, with walls 3 to 4 m (9.8 to 13.1 ft) thick. Their decoration emulated Romanesque architecture, and sometimes incorporated double windows similar to those found in church bell towers. Donjons, which were the residence of the lord of the castle, evolved to become more spacious. The design emphasis of donjons changed to reflect a shift from functional to decorative requirements, imposing a symbol of lordly power upon the landscape. This sometimes led to compromising defence for the sake of display.[86]

Innovation and scientific design (12th century)

Until the 12th century, stone-built and earth and timber castles were contemporary,[88] but by the late 12th century the number of castles being built went into decline. This has been partly attributed to the higher cost of stone-built fortifications, and the obsolescence of timber and earthwork sites, which meant it was preferable to build in more durable stone.[89] Although superseded by their stone successors, timber and earthwork castles were by no means useless.[90] This is evidenced by the continual maintenance of timber castles over long periods, sometimes several centuries; Owain Glyndŵr's 11th-century timber castle at Sycharth was still in use by the start of the 15th century, its structure having been maintained for four centuries.[91][92]

At the same time there was a change in castle architecture. Until the late 12th century castles generally had few towers; a gateway with few defensive features such as arrowslits or a portcullis; a great keep or donjon, usually square and without arrowslits; and the shape would have been dictated by the lay of the land (the result was often irregular or curvilinear structures). The design of castles was not uniform, but these were features that could be found in a typical castle in the mid-12th century.[93] By the end of the 12th century or the early 13th century, a newly constructed castle could be expected to be polygonal in shape, with towers at the corners to provide enfilading fire for the walls. The towers would have protruded from the walls and featured arrowslits on each level to allow archers to target anyone nearing or at the curtain wall.[94]

These later castles did not always have a keep, but this may have been because the more complex design of the castle as a whole drove up costs and the keep was sacrificed to save money. The larger towers provided space for habitation to make up for the loss of the donjon. Where keeps did exist, they were no longer square but polygonal or cylindrical. Gateways were more strongly defended, with the entrance to the castle usually between two half-round towers which were connected by a passage above the gateway – although there was great variety in the styles of gateway and entrances – and one or more portcullis.[94]

A peculiar feature of Muslim castles in the Iberian Peninsula was the use of detached towers, called Albarrana towers, around the perimeter as can be seen at the Alcazaba of Badajoz. Probably developed in the 12th century, the towers provided flanking fire. They were connected to the castle by removable wooden bridges, so if the towers were captured the rest of the castle was not accessible.[95]

When seeking to explain this change in the complexity and style of castles, antiquarians found their answer in the Crusades. It seemed that the Crusaders had learned much about fortification from their conflicts with the Saracens and exposure to Byzantine architecture. There were legends such as that of Lalys – an architect from Palestine who reputedly went to Wales after the Crusades and greatly enhanced the castles in the south of the country – and it was assumed that great architects such as James of Saint George originated in the East. In the mid-20th century this view was cast into doubt. Legends were discredited, and in the case of James of Saint George it was proven that he came from Saint-Georges-d'Espéranche, in France. If the innovations in fortification had derived from the East, it would have been expected for their influence to be seen from 1100 onwards, immediately after the Christians were victorious in the First Crusade (1096–1099), rather than nearly 100 years later.[97] Remains of Roman structures in Western Europe were still standing in many places, some of which had flanking round-towers and entrances between two flanking towers.

The castle builders of Western Europe were aware of and influenced by Roman design; late Roman coastal forts on the English "Saxon Shore" were reused and in Spain the wall around the city of Ávila imitated Roman architecture when it was built in 1091.[97] Historian Smail in Crusading warfare argued that the case for the influence of Eastern fortification on the West has been overstated, and that Crusaders of the 12th century in fact learned very little about scientific design from Byzantine and Saracen defences.[98] A well-sited castle that made use of natural defences and had strong ditches and walls had no need for a scientific design. An example of this approach is Kerak. Although there were no scientific elements to its design, it was almost impregnable, and in 1187 Saladin chose to lay siege to the castle and starve out its garrison rather than risk an assault.[98]

During the late 11th and 12th centuries in what is now south-central Turkey the Hospitallers, Teutonic Knights and Templars established themselves in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, where they discovered an extensive network of sophisticated fortifications which had a profound impact on the architecture of Crusader castles. Most of the Armenian military sites in Cilicia are characterized by: multiple bailey walls laid with irregular plans to follow the sinuosities of the outcrops; rounded and especially horseshoe-shaped towers; finely-cut often rusticated ashlar facing stones with intricate poured cores; concealed postern gates and complex bent entrances with slot machicolations; embrasured loopholes for archers; barrel, pointed or groined vaults over undercrofts, gates and chapels; and cisterns with elaborate scarped drains.[99] Civilian settlement are often found in the immediate proximity of these fortifications.[100] After the First Crusade, Crusaders who did not return to their homes in Europe helped found the Crusader states of the Principality of Antioch, the County of Edessa, the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the County of Tripoli. The castles they founded to secure their acquisitions were designed mostly by Syrian master-masons. Their design was very similar to that of a Roman fort or Byzantine tetrapyrgia which were square in plan and had square towers at each corner that did not project much beyond the curtain wall. The keep of these Crusader castles would have had a square plan and generally be undecorated.[101]

While castles were used to hold a site and control movement of armies, in the Holy Land some key strategic positions were left unfortified.[102] Castle architecture in the East became more complex around the late 12th and early 13th centuries after the stalemate of the Third Crusade (1189–1192). Both Christians and Muslims created fortifications, and the character of each was different. Saphadin, the 13th-century ruler of the Saracens, created structures with large rectangular towers that influenced Muslim architecture and were copied again and again, however they had little influence on Crusader castles.[103]

13th to 15th centuries

In the early 13th century, Crusader castles were mostly built by Military Orders including the Knights Hospitaller, Knights Templar, and Teutonic Knights. The orders were responsible for the foundation of sites such as Krak des Chevaliers, Margat, and Belvoir. Design varied not just between orders, but between individual castles, though it was common for those founded in this period to have concentric defences.[105]

The concept, which originated in castles such as Krak des Chevaliers, was to remove the reliance on a central strongpoint and to emphasise the defence of the curtain walls. There would be multiple rings of defensive walls, one inside the other, with the inner ring rising above the outer so that its field of fire was not completely obscured. If assailants made it past the first line of defence they would be caught in the killing ground between the inner and outer walls and have to assault the second wall.[106]

Concentric castles were widely copied across Europe, for instance when Edward I of England – who had himself been on Crusade – built castles in Wales in the late 13th century, four of the eight he founded had a concentric design.[105][106] Not all the features of the Crusader castles from the 13th century were emulated in Europe. For instance, it was common in Crusader castles to have the main gate in the side of a tower and for there to be two turns in the passageway, lengthening the time it took for someone to reach the outer enclosure. It is rare for this bent entrance to be found in Europe.[105]

One of the effects of the Livonian Crusade in the Baltic was the introduction of stone and brick fortifications. Although there were hundreds of wooden castles in Prussia and Livonia, the use of bricks and mortar was unknown in the region before the Crusaders. Until the 13th century and start of the 14th centuries, their design was heterogeneous, however this period saw the emergence of a standard plan in the region: a square plan, with four wings around a central courtyard.[107] It was common for castles in the East to have arrowslits in the curtain wall at multiple levels; contemporary builders in Europe were wary of this as they believed it weakened the wall. Arrowslits did not compromise the wall's strength, but it was not until Edward I's programme of castle building that they were widely adopted in Europe.[35]

The Crusades also led to the introduction of machicolations into Western architecture. Until the 13th century, the tops of towers had been surrounded by wooden galleries, allowing defenders to drop objects on assailants below. Although machicolations performed the same purpose as the wooden galleries, they were probably an Eastern invention rather than an evolution of the wooden form. Machicolations were used in the East long before the arrival of the Crusaders, and perhaps as early as the first half of the 8th century in Syria.[108]

The greatest period of castle building in Spain was in the 11th to 13th centuries, and they were most commonly found in the disputed borders between Christian and Muslim lands. Conflict and interaction between the two groups led to an exchange of architectural ideas, and Spanish Christians adopted the use of detached towers. The Spanish Reconquista, driving the Muslims out of the Iberian Peninsula, was complete in 1492.[95]

Although France has been described as "the heartland of medieval architecture", the English were at the forefront of castle architecture in the 12th century. French historian François Gebelin wrote: "The great revival in military architecture was led, as one would naturally expect, by the powerful kings and princes of the time; by the sons of William the Conqueror and their descendants, the Plantagenets, when they became dukes of Normandy. These were the men who built all the most typical twelfth-century fortified castles remaining today".[110] Despite this, by the beginning of the 15th century, the rate of castle construction in England and Wales went into decline. The new castles were generally of a lighter build than earlier structures and presented few innovations, although strong sites were still created such as that of Raglan in Wales. At the same time, French castle architecture came to the fore and led the way in the field of medieval fortifications. Across Europe – particularly the Baltic, Germany, and Scotland – castles were built well into the 16th century.[111]

Advent of gunpowder

Artillery powered by gunpowder was introduced to Europe in the 1320s and spread quickly. Handguns, which were initially unpredictable and inaccurate weapons, were not recorded until the 1380s.[112] Castles were adapted to allow small artillery pieces – averaging between 19.6 and 22 kg (43 and 49 lb) – to fire from towers. These guns were too heavy for a man to carry and fire, but if he supported the butt end and rested the muzzle on the edge of the gun port he could fire the weapon. The gun ports developed in this period show a unique feature, that of a horizontal timber across the opening. A hook on the end of the gun could be latched over the timber so the gunner did not have to take the full recoil of the weapon. This adaptation is found across Europe, and although the timber rarely survives, there is an intact example at Castle Doornenburg in the Netherlands. Gunports were keyhole shaped, with a circular hole at the bottom for the weapon and a narrow slit on top to allow the gunner to aim.[113]

This form is very common in castles adapted for guns, found in Egypt, Italy, Scotland, and Spain, and elsewhere in between. Other types of port, though less common, were horizontal slits – allowing only lateral movement – and large square openings, which allowed greater movement.[113] The use of guns for defence gave rise to artillery castles, such as that of Château de Ham in France. Defences against guns were not developed until a later stage.[114] Ham is an example of the trend for new castles to dispense with earlier features such as machicolations, tall towers, and crenellations.[115]

Bigger guns were developed, and in the 15th century became an alternative to siege engines such as the trebuchet. The benefits of large guns over trebuchets – the most effective siege engine of the Middle Ages before the advent of gunpowder – were those of a greater range and power. In an effort to make them more effective, guns were made ever bigger, although this hampered their ability to reach remote castles. By the 1450s guns were the preferred siege weapon, and their effectiveness was demonstrated by Mehmed II at the Fall of Constantinople.[116]

The response towards more effective cannons was to build thicker walls and to prefer round towers, as the curving sides were more likely to deflect a shot than a flat surface. While this sufficed for new castles, pre-existing structures had to find a way to cope with being battered by cannon. An earthen bank could be piled behind a castle's curtain wall to absorb some of the shock of impact.[117]

Often, castles constructed before the age of gunpowder were incapable of using guns as their wall-walks were too narrow. A solution to this was to pull down the top of a tower and to fill the lower part with the rubble to provide a surface for the guns to fire from. Lowering the defences in this way had the effect of making them easier to scale with ladders. A more popular alternative defence, which avoided damaging the castle, was to establish bulwarks beyond the castle's defences. These could be built from earth or stone and were used to mount weapons.[118]

Bastions and star forts (16th century)

Around 1500, the innovation of the angled bastion was developed in Italy.[119] With developments such as these, Italy pioneered permanent artillery fortifications, which took over from the defensive role of castles. From this evolved star forts, also known as trace italienne.[10] The elite responsible for castle construction had to choose between the new type that could withstand cannon fire and the earlier, more elaborate style. The first was ugly and uncomfortable and the latter was less secure, although it did offer greater aesthetic appeal and value as a status symbol. The second choice proved to be more popular as it became apparent that there was little point in trying to make the site genuinely defensible in the face of cannon.[120] For a variety of reasons, not least of which is that many castles have no recorded history, there is no firm number of castles built in the medieval period. However, it has been estimated that between 75,000 and 100,000 were built in western Europe;[121] of these around 1,700 were in England and Wales[122] and around 14,000 in German-speaking areas.[123]

Some true castles were built in the Americas by the Spanish and French colonies. The first stage of Spanish fort construction has been termed the "castle period", which lasted from 1492 until the end of the 16th century.[124] Starting with Fortaleza Ozama, "these castles were essentially European medieval castles transposed to America".[125] Among other defensive structures (including forts and citadels), castles were also built in New France towards the end of the 17th century.[126] In Montreal the artillery was not as developed as on the battle-fields of Europe, some of the region's outlying forts were built like the fortified manor houses of France. Fort Longueuil, built from 1695 to 1698 by a baronial family, has been described as "the most medieval-looking fort built in Canada".[127] The manor house and stables were within a fortified bailey, with a tall round turret in each corner. The "most substantial castle-like fort" near Montréal was Fort Senneville, built in 1692 with square towers connected by thick stone walls, as well as a fortified windmill.[128] Stone forts such as these served as defensive residences, as well as imposing structures to prevent Iroquois incursions.[129]

Although castle construction faded towards the end of the 16th century, castles did not necessarily all fall out of use. Some retained a role in local administration and became law courts, while others are still handed down in aristocratic families as hereditary seats. A particularly famous example of this is Windsor Castle in England which was founded in the 11th century and is home to the monarch of the United Kingdom.[130] In other cases they still had a role in defence. Tower houses, which are closely related to castles and include pele towers, were defended towers that were permanent residences built in the 14th to 17th centuries. Especially common in Ireland and Scotland, they could be up to five storeys high and succeeded common enclosure castles and were built by a greater social range of people. While unlikely to provide as much protection as a more complex castle, they offered security against raiders and other small threats.[131][132]

Later use and revival castles

According to archaeologists Oliver Creighton and Robert Higham, "the great country houses of the seventeenth to twentieth centuries were, in a social sense, the castles of their day".[133] Though there was a trend for the elite to move from castles into country houses in the 17th century, castles were not completely useless. In later conflicts, such as the English Civil War (1641–1651), many castles were refortified, although subsequently slighted to prevent them from being used again.[134] Some country residences, which were not meant to be fortified, were given a castle appearance to scare away potential invaders such as adding turrets and using small windows. An example of this is the 16th century Bubaqra Castle in Bubaqra, Malta, which was modified in the 18th century.[135]

Revival or mock castles became popular as a manifestation of a Romantic interest in the Middle Ages and chivalry, and as part of the broader Gothic Revival in architecture. Examples of these castles include Chapultepec in Mexico,[136] Neuschwanstein in Germany,[137] and Edwin Lutyens' Castle Drogo (1911–1930) – the last flicker of this movement in the British Isles.[138] While churches and cathedrals in a Gothic style could faithfully imitate medieval examples, new country houses built in a "castle style" differed internally from their medieval predecessors. This was because to be faithful to medieval design would have left the houses cold and dark by contemporary standards.[139]

Artificial ruins, built to resemble remnants of historic edifices, were also a hallmark of the period. They were usually built as centre pieces in aristocratic planned landscapes. Follies were similar, although they differed from artificial ruins in that they were not part of a planned landscape, but rather seemed to have no reason for being built. Both drew on elements of castle architecture such as castellation and towers, but served no military purpose and were solely for display.[140] A toy castle is used as a common children attraction in playing fields and fun parks, such as the castle of the Playmobil FunPark in Ħal Far, Malta.[141][142]

Construction

Once the site of a castle had been selected – whether a strategic position or one intended to dominate the landscape as a mark of power – the building material had to be selected. An earth and timber castle was cheaper and easier to erect than one built from stone. The costs involved in construction are not well-recorded, and most surviving records relate to royal castles.[143] A castle with earthen ramparts, a motte, timber defences and buildings could have been constructed by an unskilled workforce. The source of man-power was probably from the local lordship, and the tenants would already have the necessary skills of felling trees, digging, and working timber necessary for an earth and timber castle. Possibly coerced into working for their lord, the construction of an earth and timber castle would not have been a drain on a client's funds. In terms of time, it has been estimated that an average sized motte – 5 m (16 ft) high and 15 m (49 ft) wide at the summit – would have taken 50 people about 40 working days. An exceptionally expensive motte and bailey was that of Clones in Ireland, built in 1211 for UK£20. The high cost, relative to other castles of its type, was because labourers had to be imported.[143]

The cost of building a castle varied according to factors such as their complexity and transport costs for material. It is certain that stone castles cost a great deal more than those built from earth and timber. Even a very small tower, such as Peveril Castle, would have cost around UK£200. In the middle were castles such as Orford, which was built in the late 12th century for UK£1,400, and at the upper end were those such as Dover, which cost about UK£7,000 between 1181 and 1191.[144] Spending on the scale of the vast castles such as Château Gaillard (an estimated UK£15,000 to UK£20,000 between 1196 and 1198) was easily supported by The Crown, but for lords of smaller areas, castle building was a very serious and costly undertaking. It was usual for a stone castle to take the best part of a decade to finish. The cost of a large castle built over this time (anywhere from UK£1,000 to UK£10,000) would take the income from several manors, severely impacting a lord's finances.[145] Costs in the late 13th century were of a similar order, with castles such as Beaumaris and Rhuddlan costing UK£14,500 and UK£9,000 respectively. Edward I's campaign of castle-building in Wales cost UK£80,000 between 1277 and 1304, and UK£95,000 between 1277 and 1329.[146] Renowned designer Master James of Saint George, responsible for the construction of Beaumaris, explained the cost:

In case you should wonder where so much money could go in a week, we would have you know that we have needed – and shall continue to need 400 masons, both cutters and layers, together with 2,000 less-skilled workmen, 100 carts, 60 wagons, and 30 boats bringing stone and sea coal; 200 quarrymen; 30 smiths; and carpenters for putting in the joists and floor boards and other necessary jobs. All this takes no account of the garrison ... nor of purchases of material. Of which there will have to be a great quantity ... The men's pay has been and still is very much in arrears, and we are having the greatest difficulty in keeping them because they have simply nothing to live on.

— [147]

Not only were stone castles expensive to build in the first place, but their maintenance was a constant drain. They contained a lot of timber, which was often unseasoned and as a result needed careful upkeep. For example, it is documented that in the late 12th century repairs at castles such as Exeter and Gloucester cost between UK£20 and UK£50 annually.[148]

Medieval machines and inventions, such as the treadwheel crane, became indispensable during construction, and techniques of building wooden scaffolding were improved upon from Antiquity.[149] When building in stone a prominent concern of medieval builders was to have quarries close at hand. There are examples of some castles where stone was quarried on site, such as Chinon, Château de Coucy and Château Gaillard.[150] When it was built in 992 in France the stone tower at Château de Langeais was 16 metres (52 ft) high, 17.5 metres (57 ft) wide, and 10 metres (33 ft) long with walls averaging 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in). The walls contain 1,200 cubic metres (42,000 cu ft) of stone and have a total surface (both inside and out) of 1,600 square metres (17,000 sq ft). The tower is estimated to have taken 83,000 average working days to complete, most of which was unskilled labour.[151]

Many countries had both timber and stone castles,[152] however Denmark had few quarries and as a result most of its castles are earth and timber affairs, or later on built from brick.[153] Brick-built structures were not necessarily weaker than their stone-built counterparts. Brick castles are less common in England than stone or earth and timber constructions, and often it was chosen for its aesthetic appeal or because it was fashionable, encouraged by the brick architecture of the Low Countries. For example, when Tattershall Castle in England was built between 1430 and 1450, there was plenty of stone available nearby, but the owner, Lord Cromwell, chose to use brick. About 700,000 bricks were used to build the castle, which has been described as "the finest piece of medieval brick-work in England".[154] Most Spanish castles were built from stone, whereas castles in Eastern Europe were usually of timber construction.[155]

On the Construction of the Castle of Safed, written in the early 1260s, describes the construction of a new castle at Safed. It is "one of the fullest" medieval accounts of a castle's construction.[156]

Social centre

Due to the lord's presence in a castle, it was a centre of administration from where he controlled his lands. He relied on the support of those below him, as without the support of his more powerful tenants a lord could expect his power to be undermined. Successful lords regularly held court with those immediately below them on the social scale, but absentees could expect to find their influence weakened. Larger lordships could be vast, and it would be impractical for a lord to visit all his properties regularly, so deputies were appointed. This especially applied to royalty, who sometimes owned land in different countries.[159]

To allow the lord to concentrate on his duties regarding administration, he had a household of servants to take care of chores such as providing food. The household was run by a chamberlain, while a treasurer took care of the estate's written records. Royal households took essentially the same form as baronial households, although on a much larger scale and the positions were more prestigious.[160] An important role of the household servants was the preparation of food; the castle kitchens would have been a busy place when the castle was occupied, called on to provide large meals.[161] Without the presence of a lord's household, usually because he was staying elsewhere, a castle would have been a quiet place with few residents, focused on maintaining the castle.[162]

As social centres castles were important places for display. Builders took the opportunity to draw on symbolism, through the use of motifs, to evoke a sense of chivalry that was aspired to in the Middle Ages amongst the elite. Later structures of the Romantic Revival would draw on elements of castle architecture such as battlements for the same purpose. Castles have been compared with cathedrals as objects of architectural pride, and some castles incorporated gardens as ornamental features.[163] The right to crenellate, when granted by a monarch – though it was not always necessary – was important not just as it allowed a lord to defend his property but because crenellations and other accoutrements associated with castles were prestigious through their use by the elite.[164] Licences to crenellate were also proof of a relationship with or favour from the monarch, who was the one responsible for granting permission.[165]

Courtly love was the eroticisation of love between the nobility. Emphasis was placed on restraint between lovers. Though sometimes expressed through chivalric events such as tournaments, where knights would fight wearing a token from their lady, it could also be private and conducted in secret. The legend of Tristan and Iseult is one example of stories of courtly love told in the Middle Ages.[166] It was an ideal of love between two people not married to each other, although the man might be married to someone else. It was not uncommon or ignoble for a lord to be adulterous – Henry I of England had over 20 bastards for instance – but for a lady to be promiscuous was seen as dishonourable.[167]

The purpose of marriage between the medieval elites was to secure land. Girls were married in their teens, but boys did not marry until they came of age.[168] There is a popular conception that women played a peripheral role in the medieval castle household, and that it was dominated by the lord himself. This derives from the image of the castle as a martial institution, but most castles in England, France, Ireland, and Scotland were never involved in conflicts or sieges, so the domestic life is a neglected facet.[169] The lady was given a dower of her husband's estates – usually about a third – which was hers for life, and her husband would inherit on her death. It was her duty to administer them directly, as the lord administered his own land.[170] Despite generally being excluded from military service, a woman could be in charge of a castle, either on behalf of her husband or if she was widowed. Because of their influence within the medieval household, women influenced construction and design, sometimes through direct patronage; historian Charles Coulson emphasises the role of women in applying "a refined aristocratic taste" to castles due to their long term residence.[171]

Locations and landscapes

The positioning of castles was influenced by the available terrain. Whereas hill castles such as Marksburg were common in Germany, where 66 per cent of all known medieval were highland area while 34 per cent were on low-lying land,[173] they formed a minority of sites in England.[172] Because of the range of functions they had to fulfil, castles were built in a variety of locations. Multiple factors were considered when choosing a site, balancing between the need for a defendable position with other considerations such as proximity to resources. For instance many castles are located near Roman roads, which remained important transport routes in the Middle Ages, or could lead to the alteration or creation of new road systems in the area. Where available it was common to exploit pre-existing defences such as building with a Roman fort or the ramparts of an Iron Age hillfort. A prominent site that overlooked the surrounding area and offered some natural defences may also have been chosen because its visibility made it a symbol of power.[174] Urban castles were particularly important in controlling centres of population and production, especially with an invading force, for instance in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of England in the 11th century the majority of royal castles were built in or near towns.[175]

_jeste_lepe.jpg.webp)

As castles were not simply military buildings but centres of administration and symbols of power, they had a significant impact on the surrounding landscape. Placed by a frequently-used road or river, the toll castle ensured that a lord would get his due toll money from merchants. Rural castles were often associated with mills and field systems due to their role in managing the lord's estate,[176] which gave them greater influence over resources.[177] Others were adjacent to or in royal forests or deer parks and were important in their upkeep. Fish ponds were a luxury of the lordly elite, and many were found next to castles. Not only were they practical in that they ensured a water supply and fresh fish, but they were a status symbol as they were expensive to build and maintain.[178]

Although sometimes the construction of a castle led to the destruction of a village, such as at Eaton Socon in England, it was more common for the villages nearby to have grown as a result of the presence of a castle. Sometimes planned towns or villages were created around a castle.[176] The benefits of castle building on settlements was not confined to Europe. When the 13th-century Safad Castle was founded in Galilee in the Holy Land, the 260 villages benefitted from the inhabitants' newfound ability to move freely.[179] When built, a castle could result in the restructuring of the local landscape, with roads moved for the convenience of the lord.[180] Settlements could also grow naturally around a castle, rather than being planned, due to the benefits of proximity to an economic centre in a rural landscape and the safety given by the defences. Not all such settlements survived, as once the castle lost its importance – perhaps succeeded by a manor house as the centre of administration – the benefits of living next to a castle vanished and the settlement depopulated.[181]

During and shortly after the Norman Conquest of England, castles were inserted into important pre-existing towns to control and subdue the populace. They were usually located near any existing town defences, such as Roman walls, although this sometimes resulted in the demolition of structures occupying the desired site. In Lincoln, 166 houses were destroyed to clear space for the castle, and in York agricultural land was flooded to create a moat for the castle. As the military importance of urban castles waned from their early origins, they became more important as centres of administration, and their financial and judicial roles.[182] When the Normans invaded Ireland, Scotland, and Wales in the 11th and 12th centuries, settlement in those countries was predominantly non-urban, and the foundation of towns was often linked with the creation of a castle.[183]

The location of castles in relation to high status features, such as fish ponds, was a statement of power and control of resources. Also often found near a castle, sometimes within its defences, was the parish church.[186] This signified a close relationship between feudal lords and the Church, one of the most important institutions of medieval society.[187] Even elements of castle architecture that have usually been interpreted as military could be used for display. The water features of Kenilworth Castle in England – comprising a moat and several satellite ponds – forced anyone approaching a water castle entrance to take a very indirect route, walking around the defences before the final approach towards the gateway.[188] Another example is that of the 14th-century Bodiam Castle, also in England; although it appears to be a state of the art, advanced castle it is in a site of little strategic importance, and the moat was shallow and more likely intended to make the site appear impressive than as a defence against mining. The approach was long and took the viewer around the castle, ensuring they got a good look before entering. Moreover, the gunports were impractical and unlikely to have been effective.[189]

Warfare

As a static structure, castles could often be avoided. Their immediate area of influence was about 400 metres (1,300 ft) and their weapons had a short range even early in the age of artillery. However, leaving an enemy behind would allow them to interfere with communications and make raids. Garrisons were expensive and as a result often small unless the castle was important.[191] Cost also meant that in peacetime garrisons were smaller, and small castles were manned by perhaps a couple of watchmen and gate-guards. Even in war, garrisons were not necessarily large as too many people in a defending force would strain supplies and impair the castle's ability to withstand a long siege. In 1403, a force of 37 archers successfully defended Caernarfon Castle against two assaults by Owain Glyndŵr's allies during a long siege, demonstrating that a small force could be effective.[192]

Early on, manning a castle was a feudal duty of vassals to their magnates, and magnates to their kings, however this was later replaced with paid forces.[192][193] A garrison was usually commanded by a constable whose peacetime role would have been looking after the castle in the owner's absence. Under him would have been knights who by benefit of their military training would have acted as a type of officer class. Below them were archers and bowmen, whose role was to prevent the enemy reaching the walls as can be seen by the positioning of arrowslits.[194]

If it was necessary to seize control of a castle an army could either launch an assault or lay siege. It was more efficient to starve the garrison out than to assault it, particularly for the most heavily defended sites. Without relief from an external source, the defenders would eventually submit. Sieges could last weeks, months, and in rare cases years if the supplies of food and water were plentiful. A long siege could slow down the army, allowing help to come or for the enemy to prepare a larger force for later.[195] Such an approach was not confined to castles, but was also applied to the fortified towns of the day.[196] On occasion, siege castles would be built to defend the besiegers from a sudden sally and would have been abandoned after the siege ended one way or another.[197]

If forced to assault a castle, there were many options available to the attackers. For wooden structures, such as early motte-and-baileys, fire was a real threat and attempts would be made to set them alight as can be seen in the Bayeux Tapestry.[198] Projectile weapons had been used since antiquity and the mangonel and petraria – from Eastern and Roman origins respectively – were the main two that were used into the Middle Ages. The trebuchet, which probably evolved from the petraria in the 13th century, was the most effective siege weapon before the development of cannons. These weapons were vulnerable to fire from the castle as they had a short range and were large machines. Conversely, weapons such as trebuchets could be fired from within the castle due to the high trajectory of its projectile, and would be protected from direct fire by the curtain walls.[199]

Ballistas or springalds were siege engines that worked on the same principles as crossbows. With their origins in Ancient Greece, tension was used to project a bolt or javelin. Missiles fired from these engines had a lower trajectory than trebuchets or mangonels and were more accurate. They were more commonly used against the garrison rather than the buildings of a castle.[200] Eventually cannons developed to the point where they were more powerful and had a greater range than the trebuchet, and became the main weapon in siege warfare.[116]

Walls could be undermined by a sap. A mine leading to the wall would be dug and once the target had been reached, the wooden supports preventing the tunnel from collapsing would be burned. It would cave in and bring down the structure above.[201] Building a castle on a rock outcrop or surrounding it with a wide, deep moat helped prevent this. A counter-mine could be dug towards the besiegers' tunnel; assuming the two converged, this would result in underground hand-to-hand combat. Mining was so effective that during the siege of Margat in 1285 when the garrison were informed a sap was being dug they surrendered.[202] Battering rams were also used, usually in the form of a tree trunk given an iron cap. They were used to force open the castle gates, although they were sometimes used against walls with less effect.[203]

As an alternative to the time-consuming task of creating a breach, an escalade could be attempted to capture the walls with fighting along the walkways behind the battlements.[204] In this instance, attackers would be vulnerable to arrowfire.[205] A safer option for those assaulting a castle was to use a siege tower, sometimes called a belfry. Once ditches around a castle were partially filled in, these wooden, movable towers could be pushed against the curtain wall. As well as offering some protection for those inside, a siege tower could overlook the interior of a castle, giving bowmen an advantageous position from which to unleash missiles.[204]

See also

- Alcázar

- Burgstall

- Cave castle

- Concentric castle

- Fortified house

- Hill castle

- Hillside castle

- Island castle

- Lowland castle

- Ridge castle

- Spur castle

- Toll castle

- Water castle

Castle features:

- Arrowslit

- Battlement

- Drawbar (defense)

- Drawbridge

- Dungeon

- Hoarding

- Keep

- Medieval fortification

- Murder hole

Similar structures:

- African castles

- Dzong architecture

- Forts in India

- Fortified church

- Gusuku

- Japanese castle

- Tower house

Footnotes

- A 'pleasance' is a style of walled-in royal or noble residence, used by some nobility in the late medieval period. In particular, a 'pleasance' necessarily had extensive, elaborate gardens; these are sometimes called by the modern descriptive phrase "stately pleasure gardens". They were built in northern Europe after gunpowder and cannon had obsoleted the early medieval military castles. In general, a 'pleasance' was intentionally built to resemble a militarily-functional castle, so that it could serve as what one could call "landscape propaganda" – a reminder to those viewing it from the outside of the superior power and status of the resident nobility which had been dispatched from castle garrisons in the prior generation(s). And a 'pleasance' was built to resemble those remembered castles, even though to reduce expense, the walls were not adequate as fortifications, as-built;[1] with the possible exception of those (if any) made by remodelling obsolete, formerly functional castles.

References

- Tregruk (recorded television program). Time Team. Tregruk settlement, Llangybi village, town of Pontypool, Monmouth shire, UK: Channel 4. 2013-03-11 [2010-10-10]. season 17, episode 8. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 2021-08-14 – via YouTube.

- Creighton & Higham 2003, p. 6, chpt 1

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 32

- Coulson 2003, p. 16

- Liddiard 2005, pp. 15–17

- Herlihy 1970, p. xvii–xviii

- Friar 2003, p. 47

- Liddiard 2005, p. 18

- Stephens 1969, pp. 452–475

- Duffy 1979, pp. 23–25

- Liddiard 2005, pp. 2, 6–7

- Cathcart King 1983, pp. xvi–xvii

- Liddiard 2005, p. 2

- Creighton & Higham 2003, pp. 6–7

- Thompson 1987, pp. 1–2, 158–159

- Allen Brown 1976, pp. 2–6

- Turnbull 2003, p. 5

- Turnbull 2003, p. 4

- Nossov 2006, p. 8

- Friar 2003, p. 214

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 55–56

- Barthélemy 1988, p. 397

- Friar 2003, p. 22

- Barthélemy 1988, pp. 408–410, 412–414

- Friar 2003, pp. 214, 216

- Friar 2003, p. 105

- Barthélemy 1988, p. 399

- Friar 2003, p. 163

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 188

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 190

- Barthélemy 1988, p. 402

- Barthélemy 1988, pp. 402–406

- Barthélemy 1988, pp. 416–422

- Friar 2003, p. 86

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 84

- Friar 2003, pp. 124–125

- Friar 2003, pp. 126, 232

- McNeill 1992, pp. 98–99

- Jaccarini, C. J. (2002). "Il-Muxrabija, wirt l-Iżlam fil-Gżejjer Maltin" (PDF). L-Imnara (in Maltese). Rivista tal-Għaqda Maltija tal-Folklor. 7 (1): 19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2016.

- Azzopardi, Joe (April 2012). "A Survey of the Maltese Muxrabijiet" (PDF). Vigilo. Valletta: Din l-Art Ħelwa (41): 26–33. ISSN 1026-132X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2015.

- Allen Brown 1976, p. 64

- Friar 2003, p. 25

- McNeill 1992, p. 101

- Allen Brown 1976, p. 68

- Friar 2003, p. 208

- Liddiard 2005, p. 10.

- Taylor 2000, pp. 40–41.

- Friar 2003, pp. 210–211

- Friar 2003, p. 32

- Friar 2003, pp. 180–182

- Friar 2003, p. 254

- Johnson 2002, p. 20

- The Medieval castle. St. Cloud, Minn: North Star Press of St. Cloud. 1991. p. 17. ISBN 9780816620036. Archived from the original on 25 November 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- Lepage 2002, p. 123.

- Seka Brkljača (1996). Urbano biće Bosne i Hercegovine (in Serbo-Croatian). Sarajevo: Međunarodni centar za mir, Institut za istoriju. p. 27. Archived from the original on 25 November 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- "The natural and architectural ensemble of Stolac". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- Zammit, Vincent (1984). "Maltese Fortifications". Civilization. Ħamrun: PEG Ltd. 1: 22–25. See also Fortifications of Malta#Ancient and Medieval fortifications (pre-1530)

- Coulson 2003, p. 15.

- Cunliffe 1998, p. 420.

- Fernández-Götz, Manuel (December 2019). "A World of 200 Oppida: Pre-Roman Urbanism in Temperate Europe Oppida". In de Ligt, Luuk; Bintliff, John (eds.). Regional Urban Systems in the Roman World, 150 BCE – 250 CE. Brill. pp. 35–66. ISBN 978-90-04-41436-5.

- Ralston, Ian (1995). "Fortifications and defence". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 9781135632434.

- Ward 2009, p. 7.

- Creighton 2012, pp. 27–29, 45–48

- Allen Brown 1976, pp. 6–8

- Coulson 2003, pp. 18, 24

- Creighton 2012, pp. 44–45

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 35

- Allen Brown 1976, p. 12

- Friar 2003, p. 246

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 35–36

- Allen Brown 1976, p. 9

- Cathcart King 1983, pp. xvi–xx

- Allen Brown 1984, p. 13

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 24–25

- Allen Brown 1976, pp. 8–9

- Aurell 2006, pp. 32–33

- Aurell 2006, p. 33

- Higham & Barker 1992, p. 79

- Higham & Barker 1992, pp. 78–79

- Burton 2007–2008, pp. 229–230

- Vann 2006, p. 222

- Friar 2003, p. 95

- Aurell 2006, p. 34

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 32–34

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 26

- Aurell 2006, pp. 33–34

- Friar 2003, pp. 95–96

- Allen Brown 1976, p. 13

- Allen Brown 1976, pp. 108–109

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 29–30

- Friar 2003, p. 215

- Norris 2004, pp. 122–123

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 77

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 77–78

- Burton 2007–2008, pp. 241–243

- Allen Brown 1976, pp. 64, 67

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 78–79

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 29

- Edwards, Robert W. (1987). The Fortifications of Armenian Cilicia: Dumbarton Oaks Studies XXIII. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. pp. 3–282. ISBN 0-88402-163-7.

- Edwards, Robert W., "Settlements and Toponymy in Armenian Cilicia," Revue des Études Arméniennes 24, 1993, pp.181-204.

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 80

- Cathcart King 1983, pp. xx–xxii

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 81–82

- Crac des Chevaliers and Qal'at Salah El-Din, UNESCO, archived from the original on 2019-12-02, retrieved 2009-10-20

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 83

- Friar 2003, p. 77

- Ekdahl 2006, p. 214

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 84–87

- Cassar, George (2014). "Defending a Mediterranean island outpost of the Spanish Empire – the case of Malta". Sacra Militia (13): 59–68. Archived from the original on 2021-08-31. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- Gebelin 1964, pp. 43, 47, quoted in Cathcart King 1988, p. 91

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 159–160

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 164–165

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 165–167

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 168

- Thompson 1987, pp. 40–41

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 169

- Thompson 1987, p. 38

- Thompson 1987, pp. 38–39

- Thompson 1987, pp. 41–42

- Thompson 1987, p. 42

- Thompson 1987, p. 4

- Cathcart King 1983

- Tillman 1958, p. viii, cited in Thompson 1987, p. 4

- Chartrand & Spedaliere 2006, pp. 4–5

- Chartrand & Spedaliere 2006, p. 4

- Chartrand 2005

- Chartrand 2005, p. 39

- Chartrand 2005, p. 38

- Chartrand 2005, p. 37

- Creighton & Higham 2003, p. 64

- Thompson 1987, p. 22

- Friar 2003, pp. 286–287

- Creighton & Higham 2003, p. 63

- Friar 2003, p. 59

- Guillaumier, Alfie (2005). Bliet u Rhula Maltin. Vol. 2. Klabb Kotba Maltin. p. 1028. ISBN 99932-39-40-2.

- Antecedentes históricos (in Spanish), Museo Nacional de Historia, archived from the original on 2009-11-14, retrieved 2009-11-24

- Buse 2005, p. 32

- Thompson 1987, p. 166

- Thompson 1987, p. 164

- Friar 2003, p. 17

- Kollewe, Julia (30 May 2011). "Playmobil's theme park in Malta has captured children's imagination". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016.

- Gallagher, Mary-Ann (1 March 2007). Top 10 Malta & Gozo. Dorling Kindersley Ltd. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4053-1784-9. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2017 – via Google Books.

- McNeill 1992, pp. 39–40

- McNeill 1992, pp. 41–42

- McNeill 1992, p. 42

- McNeill 1992, pp. 42–43

- McNeill 1992, p. 43

- McNeill 1992, pp. 40–41

- Erlande-Brandenburg 1995, pp. 121–126

- Erlande-Brandenburg 1995, p. 104

- Bachrach 1991, pp. 47–52

- Higham & Barker 1992, p. 78

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 25

- Friar 2003, pp. 38–40

- Higham & Barker 1992, pp. 79, 84–88

- Kennedy 1994, p. 190.

- "Castle of the Teutonic Order in Malbork". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- Emery 2007, p. 139

- McNeill 1992, pp. 16–18

- McNeill 1992, pp. 22–24

- Friar 2003, p. 172

- McNeill 1992, pp. 28–29

- Coulson 1979, pp. 74–76

- Coulson 1979, pp. 84–85

- Liddiard 2005, p. 9

- Schultz 2006, pp. xv–xxi

- Gies & Gies 1974, pp. 87–90

- McNeill 1992, pp. 19–21

- Coulson 2003, p. 382

- McNeill 1992, p. 19

- Coulson 2003, pp. 297–299, 382

- Creighton 2002, p. 64

- Krahe 2002, pp. 21–23

- Creighton 2002, pp. 35–41

- Creighton 2002, p. 36

- Creighton & Higham 2003, pp. 55–56

- Creighton 2002, pp. 181–182

- Creighton 2002, pp. 184–185

- Smail 1973, p. 90

- Creighton 2002, p. 198

- Creighton 2002, pp. 180–181, 217

- Creighton & Higham 2003, pp. 58–59

- Creighton & Higham 2003, pp. 59–63

- "Historia (History)". Hämeen linna [Häme Castle]. Museot ja linnat (Museums and Castles) (Report) (in Finnish). Tervetuloa Suomen kansallismuseoon (National Museum of Finland). Archived from the original on 2020-06-15. Retrieved 2020-06-15 – via Kansallismuseo (National Museum) (www.kansallismuseo.fi).

- Gardberg & Welin 2003, p. 51

- Creighton 2002, p. 221

- Creighton 2002, pp. 110, 131–132

- Creighton 2002, pp. 76–79

- Liddiard 2005, pp. 7–10

- Creighton 2002, pp. 79–80

- Cathcart King 1983, pp. xx–xxiii

- Friar 2003, pp. 123–124

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 15–18

- Allen Brown 1976, pp. 132, 136

- Liddiard 2005, p. 84

- Friar 2003, p. 264

- Friar 2003, p. 263

- Allen Brown 1976, p. 124

- Cathcart King 1988, pp. 125–126, 169

- Allen Brown 1976, pp. 126–127

- Friar 2003, pp. 254, 262

- Allen Brown 1976, p. 130

- Friar 2003, p. 262

- Allen Brown 1976, p. 131

- Cathcart King 1988, p. 127

Bibliography

- Allen Brown, Reginald (1976) [1954]. Allen Brown's English Castles. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-069-8.

- Allen Brown, Reginald (1984). The Architecture of Castles: A Visual Guide. B.T. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-4089-9.

- Aurell, Martin (2006). "Society". In Power, Daniel (ed.). The Short Oxford History of Europe. The Central Middle Ages: Europe 950–1320. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925312-9.

- Bachrach, Bernard S. (1991). "The Cost of Castle Building: The case of the tower at Langeais, 992–994". In Reyerson, Kathryn L.; Powe, Faye (eds.). The Medieval Castle: Romance and reality. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 47–62. ISBN 978-0-8166-2003-6.