Palmyra Atoll

Palmyra Atoll (/pælˈmaɪrə/), also referred to as Palmyra Island, is one of the Northern Line Islands (southeast of Kingman Reef and north of Kiribati). It is located almost due south of the Hawaiian Islands, roughly one-third of the way between Hawaii and American Samoa. North America is about 3,300 miles (5,300 kilometers) northeast and New Zealand the same distance southwest, placing the atoll at the approximate center of the Pacific Ocean. The land area is 4.6 sq mi (12 km2), with about 9 miles (14 km) of sea-facing coastline and reef. There is one boat anchorage known as West Lagoon, accessible from the sea by a narrow artificial channel.

Palmyra Atoll | |

|---|---|

| Territory of Palmyra Island | |

Palmyra Atoll visitor access map | |

.svg.png.webp) Location of Palmyra Atoll in the Pacific Ocean | |

| Sovereign state | United States |

| Annexed by the United States | June 14, 1900 |

| Named for | U.S. trading ship Palmyra |

| Government | National Wildlife Refuge |

• Administered by | United States Fish and Wildlife Service |

• Superintendent | Laura Beauregard, Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument |

| Area | |

• Land | 11.9 km2 (4.6 sq mi) |

• Water | 0 km2 (0 sq mi) |

| Dimensions | |

• Length | 4.7 km (2.9 mi) |

• Width | 6.8 km (4.2 mi) |

| Elevation | 7 ft (2.1 m) |

| Highest elevation (Sand Island) | 30 ft (10 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 4–20 staff and scientists |

| Currency | United States dollar (US$) (USD) |

| Time zone | UTC−11:00 (SST) |

| ISO 3166 code |

|

| Internet TLD | .us |

IUCN category Ia (strict nature reserve) | |

| Designated | 2001 |

| Official name | Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge |

| Designated | April 1, 2011 |

| Reference no. | 1971[1] |

It is the second-to-northernmost of the Line Islands, and one of three American islands in the archipelago, along with Jarvis Island and Kingman Reef. Palmyra Atoll is part of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, the world's largest marine protected area. The atoll is composed of submerged sand flats along with dry land and reefs. It consists of three lagoons separated by coral reefs. The western reef terrace is one of the biggest shelf-reefs, with dimensions of 2 by 3 miles (3.2 by 4.8 km). Over 150 species of coral inhabit Palmyra Atoll, double the number recorded in Hawaii.[2]

Palmyra Atoll has no permanent population. It is administered as an incorporated unorganized territory, presently the only one of its kind, by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior. The territory hosts a variable transient population of 4–25 staff and scientists employed by various departments of the U.S. government and by The Nature Conservancy,[3] as well as a rotating mix of Palmyra Atoll Research Consortium[4] scholars. Submerged portions of the atoll are administered by the Department of the Interior's Office of Insular Affairs.[5]

Geography

The atoll consists of an extensive reef, three shallow lagoons, and a number of sand and reef-rock islets and bars covered with vegetation—mostly coconut palms, scaevola, and tall pisonia trees.

Many of the islets are connected. Sand Island and the two Home Islets in the west; Quail, Whippoorwill, and Bunker Islands in the north; and Eastern, Fern, Bird and Barren Islands in the east are not. The largest island is Cooper Island in the north, followed by Kaula Island in the south. The northern arch of islets is formed by Strawn Island, Cooper Island (or Cooper-Meng Island since the original Cooper and Meng Islands were joined in 1940), Aviation Island, Quail Island, Whippoorwill Island, Bunker Island, followed in the east by Eastern Island, Papala Island and Pelican Island, and in the south by Bird Island, Holei Island, Engineer Island, Tanager Island, Marine Island, Kaula Island, Paradise Island, the Home Islets, and Sand Island (clockwise).

Palmyra Atoll is in the Samoa Time Zone (UTC−11:00), the same time zone as American Samoa, Midway Atoll, Kingman Reef and Jarvis Island.

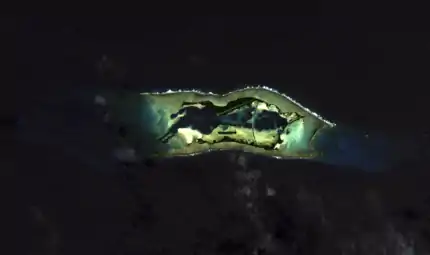

Palmyra Atoll, 2010 satellite image

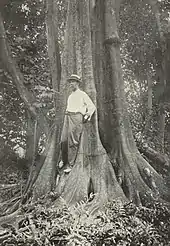

Palmyra Atoll, 2010 satellite image.jpg.webp) Coconut palms on Strawn Island at Palmyra Atoll

Coconut palms on Strawn Island at Palmyra Atoll

Incorporated in the United States

In The Insular Cases, the Supreme Court held incorporated territories to be integral parts of the United States, as opposed to mere possessions. The incorporated Palmyra Atoll is the southernmost point of the incorporated United States, with its southernmost shore at 5°52'15" N latitude. U.S.-controlled territories such as American Samoa (and the southernmost place, Rose Atoll) are farther south, but they are not incorporated territories.[6][7]

Climate

Average annual rainfall is approximately 175 in (4,400 mm) per year. Temperatures average 85 °F (29 °C) year round. The atoll has nearly the highest oceanicity index (i.e. degree to which its climate is affected by the sea) and one of the lowest diurnal and annual temperature variation of any place on earth. Nauru has more consistent nighttime temperatures with every month recording 77 °F (25 C) average, as well as more evenly spread precipitation.

| Climate data for Palmyra Atoll | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28.9 (84.0) |

28.3 (83.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

29.4 (85.0) |

29.4 (85.0) |

29.4 (85.0) |

29.4 (85.0) |

29.4 (85.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.4 (85.0) |

29.4 (85.0) |

29.4 (85.0) |

29.3 (84.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.7 (80.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.7 (80.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.7 (80.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.7 (80.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.9 (80.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 24.4 (76.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.4 (76.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.4 (76.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.4 (76.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 340 (13.3) |

220 (8.5) |

250 (9.8) |

190 (7.3) |

310 (12.1) |

420 (16.6) |

430 (17.1) |

510 (20.1) |

280 (10.9) |

250 (10.0) |

360 (14.3) |

520 (20.3) |

4,080 (160.3) |

| Average rainy days | 14.5 | 12.3 | 15.3 | 11.8 | 17.2 | 17.9 | 20.2 | 19.8 | 13.6 | 14.3 | 14.5 | 16.5 | 187.9 |

| Source: Weatherbase.com[8] | |||||||||||||

Official names

Although Palmyra is a coral atoll with several islets, not a single island, it has been called Palmyra Island since the first visit in 1802.[9] More recently it is for some purposes called Palmyra Atoll. The name of the federal territory retained by Congress since 1959 is Palmyra Island,[10] but the official name of the National Wildlife Refuge within the territory is Palmyra Atoll, as is the corresponding division of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.[11] Formal deeds, leases and federal orders for land there call it Palmyra Island.[12] Further, the islets on the atoll are also named island, such as Kaula Island, Cooper Island, and others.[13]

Political status

Palmyra is an incorporated territory of the United States (the only such territory since 1959), meaning that it is subject to all provisions of the U.S. Constitution and is permanently under American sovereignty. Palmyra remains an unorganized territory. No Act of Congress since Hawaii statehood in 1959 has specified how Palmyra is to be governed. Palmyra has no permanent residents. In 2004 accommodations were built to support a small number of temporary inhabitants.

The only relevant federal law gives the president the authority to administer Palmyra as directed, or via the United States District Court for the District of Hawaii (Hawaii Omnibus Act, Pub. L. 86–624, July 12, 1960, 74 Stat. 411).[10]

The issue of governance is generally a moot point since no permanent population lives there. Cooper Island and ten other land parcels in this atoll are owned by The Nature Conservancy, Inc. (TNC), which manages them as a nature reserve. The southwesternmost islets, including Home, are owned by descendants of former Palmyra owner Henry Ernest Cooper and others. The rest of Palmyra is federal land and waters under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[14] Since Palmyra has no state or local government, it is administered directly from Honolulu by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, except for some submerged tracts administered by the Office of Insular Affairs, both in the U.S. Department of the Interior. For all other purposes, Palmyra is counted as one of the U.S. minor outlying islands. They are outside of the customs territory of the United States and have no customs duties.[15][16]

Palmyra land was registered in Hawaii Land Court in 1912.[17] In 1959, the rest of the federal Territory of Hawaii, excluding Palmyra, became the state of Hawaii. Hawaii Land Court became a state court and lost jurisdiction over Palmyra land. Instead, Palmyra land documents are filed or recorded in federal court in Honolulu.[12]

Economy

The only current economic activity on Palmyra is paid ecotourism visits by TNC donors. Most of the roads and causeways there were built during World War II. Most of these are now unserviceable and overgrown, and most causeways and many of the filled areas between islets have washed-away gaps. A 2,000-yard-long (1,800 m) unpaved airstrip on Cooper Island (Palmyra (Cooper) Airport, ICAO code PLPA) was built for the Palmyra Island Naval Air Station before and during World War II.

A construction program in 2004 erected 16 two-person bungalows, a galley/dining area, several maintenance and storage facilities, and a communal block of toilets and showers for the temporary residents. Fresh water is collected from the roof of a 100,000 gallon above-ground concrete cistern in the center of the island. The communal buildings of the area on the southwestern coast of Cooper Island (the only occupied area of the atoll) consist of about a half dozen buildings next to a World War II-era steel ripple wharf, a former seaplane ramp now used as a boat launch ramp, and a more recently built floating dock.

Airport

Palmyra (Cooper) Airport (ICAO: PLPA, FAA LID: P16) is an unattended airport on Palmyra Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. It is a private-use facility, originally built during World War II and now owned by The Nature Conservancy. It has one runway (6/24) measuring 5,000 ft × 150 ft (1,524 m × 46 m).[18] When built the airport was called Palmyra Atoll Airfield, and later Palmyra Island Naval Air Station as it was a former Naval airfield on the Palmyra Atoll in the Line Islands of the Central Pacific Area. The name for the airport comes from Henry Ernest Cooper, Sr. (1857–1929) who owned Palmyra from 1911 to 1922.[19]

Preliminary surveys were made by the U.S. Navy in 1938 for an airfield at this location. The first Navy group to begin construction sailed from Honolulu on November 14, 1939. The runway was made from crushed coral and expanded during World War II. During World War II, the U.S. Naval Construction Battalion dredged a channel so that ships could enter the protected lagoons, and bulldozed coral rubble into a long, unpaved landing strip for refueling transpacific supply planes at the airbase. On January 16, 1942, six Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers from Hawaii were stationed at the airbase, Commanded by Lt. Col. Walter C. Sweeney Jr. as part of Hawaiian Air Force's Task Group 8. Marine Corps VMF-211 pilots also used the airfield.[20] During World War II, two other runways were built and used, one on Meng island and one on Sand Island. Both of these runways are now overgrown with plants and returning to jungle. The U.S. Air Force maintained the main airfield until 1961.[21][22]

The airstrip still exists today but can only be used after prior permission has been obtained or in case of emergency.[23]

History

Discovery

The first known sighting of Palmyra came in 1798 aboard the American sealing ship Betsy, on a voyage to Asia, according to the memoir of Captain Edmund Fanning of Stonington, Connecticut.[24] Fanning wrote that he had awakened three times during the night before, and after the third time took it as a premonition, ordering Betsy to heave to for the rest of the night. The next morning, Betsy resumed sailing, but only about a nautical mile further on, he believed that he sighted the reef later known as Palmyra Island. Had the ship continued on her course at night, it might have been wrecked.[25] Captain Fanning's claim to have discovered Palmyra itself has been challenged, on the view that he had only reached Kingman Reef 34 miles (55 kilometers) away and could not possibly have seen Palmyra from that distance.[26] On page 3, the Baltimore newspaper The Telegraphe and Daily Advertiser of July 29, 1803, appears to quote directly from Fanning's journal: "We supposed that we saw land from the masthead to the southward of the shoal (Kingman Reef) but it was so hazy we were not certain." This would stand in conflict with Fanning's book of 1833, in which he, while referring to Kingman Reef, wrote "I went aloft, and with the aid of the glass could plainly see the land over it, far in the south."[27]

On November 7, 1802, the ship Palmyra, under Captain Cornelius Sowle (sometimes spelled "Sawle"), was shipwrecked on the reef, which took the vessel's name.[28] Lacking a navigable boat passage through the reef from the sea, it had never been inhabited. A lack of archaeological surveys on the atoll leave the question of habitation prior to European contact open. As a result, no marae, basalt artifacts or evidence of Polynesian, Micronesian or other pre-European native settlements before 1802 have been reported on Palmyra.[29] At the time of his discovery, Captain Sowle wrote:

There are no inhabitants on the island, nor was any fresh water found; but cocoanuts [sic] of a very large size, are in great abundance; and fish of various kinds and in large shoals surround the land.[30][9]

Esperanza treasure

During the 19th and 20th centuries, stories circulated in the Pacific of a large treasure of gold, silver and precious stones (sometimes described as Inca treasures) that had been looted in the Viceroyalty of Peru.[31] A crew loaded it in secret onto the ship Esperanza in Callao harbor, Peru, and embarked into the Pacific Ocean on January 1, 1816, bound for the Spanish West Indies.

According to a survivor, seaman James Hines, the Esperanza was caught in a storm that dismasted and damaged the ship, after which it was attacked and boarded by pirates, who loaded the treasure and surviving crew onto their own ship. The Esperanza sank, and the pirates and their captives sailed west across the Pacific bound for Macao.

After 43 days, the pirates' ship met a storm, lost course, and struck the coral reef surrounding Palmyra Island, breaking the mast. The 90 men aboard were able to pull the ship closer to land, but it was not serviceable. They offloaded the treasure to the island, distributed some, and buried the rest. They repaired part of their boat and most of the crew shipped away, not to be heard from again. The remaining ten men spent most of a year on Palmyra living on dwindling stores and local food. They spent three months building a small escape boat, upon which six men left Palmyra. Of these, four were washed overboard in a storm and the other two were rescued by an American whaler bound for San Francisco. One died en route. The survivor, James Hines, was put in a hospital, but he died 30 days later.

Before Hines died, he wrote letters describing the affair and the location of the treasure, which originally included 1.5 million Spanish gold pesos and an equal value in silver (possibly consisting of precolumbian artworks). Around 1903, over 95 years later, the letters were allegedly deposited for safekeeping with Capt. William R. Foster, the harbormaster of Honolulu, by a sailor who was bound for the Solomon Islands but never returned. After holding the letters for 20 years in an iron chest, Foster revealed them to a reporter, who published the details.[32] A conflicting variant of the story was published by Capt. F. D. Walker of Honolulu in 1903[33] and in 1914.[34] In 1997, William A. Warren filed a federal salvage claim for a ship sunk off the atoll that he claimed had treasure from the Esperanza, but he abandoned his claim after legal objection from the Fullard-Leos, who owned most of Palmyra.[35]

The legend of the Esperanza and Santa Rosa (a ship rumored to have recovered the Esperanza treasure and sailed back to Honolulu) inspired a Jack London story called "The Proud Goat of Aloysius Pankburn", which was published as part of London's David Grief stories in the Saturday Evening Post.[36][37]

American visits

The atoll was visited by the USS Porpoise in 1842 as part of the United States Exploring Expedition, led by Charles Wilkes. This marked the first visit to Palmyra by a scientific expedition. Various live samples of native plants and animals were collected. In his 23rd volume recording the findings of the USXX, Wilkes wrote of Palmyra, mentioning some unspecified inhabitants at that time:

This island is inhabited ... It is to be regretted that all these detached islands should not be visited by our national vessels, and friendly intercourse kept up with them. The benefit and assistance that any shipwrecked mariners might derive from their rude inhabitants, would repay the time, trouble, and expense such visits would occasion.[38]

In 1859, Palmyra Atoll was claimed for the United States both by Alfred Benson and by Dr. Gerrit P. Judd of the brig Josephine, in accordance with the Guano Islands Act of 1856, but no guano was there to be mined, so the claims were abandoned.[39]

Annexation by the Kingdom of Hawaii (1862)

On February 26, 1862, King Kamehameha IV of Hawaii commissioned Captain Zenas Bent and Johnson Beswick Wilkinson, both Hawaiian citizens, to take possession of the atoll. On April 15, 1862, it was formally annexed to the Kingdom of Hawaii, while Bent and Wilkinson became joint owners.[40]

Over the next century, ownership passed through various hands. Bent sold his rights to Wilkinson on December 25, 1862. Palmyra later passed to Kalama Wilkinson (Johnson's widow). In 1885, it was divided among her four heirs,[41] two of whom sold their rights to William Luther Wilcox who, in turn, sold them to the Pacific Navigation Company. In 1897, this company was liquidated, and its interests were sold first to William Ansel Kinney, and then to Fred Wundenberg, all of Honolulu.[42] On June 12, 1911, Wundenberg's widow sold his two-thirds undivided interest in Palmyra as a tenant in common to Judge Henry Ernest Cooper (1857–1929).[43]

A further Wilkinson heir left her share to her son William Ringer, Sr., who also bought his great-uncle's share, giving Ringer a one-third undivided share as a tenant in common.[44]

Meanwhile, in 1889, Commander Nichols of HMS Cormorant claimed Palmyra for the United Kingdom, unaware of the prior claim made by Hawaii.[45]

Part of the U.S. Territory of Hawaii (1900–1959)

In 1898, the United States by the Newlands Resolution annexed the Republic of Hawaii, formerly the Provisional Government of Hawaii, and Palmyra with it. An Act of Congress made all of Hawaii, including Palmyra, into an "incorporated territory" of the United States at that time. (Act of April 30, 1900, ch. 339, §§ 4–5.) On June 14, 1900, Palmyra became part of the new U.S. Territory of Hawaii.[40]

With the imminent opening of the Panama Canal, Palmyra became strategically important. Britain had established a submarine cable station for the All Red Line on nearby Fanning Island.[46] The U.S. Navy sent USS West Virginia to Palmyra, where on February 21, 1912, American sovereignty was formally reaffirmed.[40]

William Ringer, Sr. died in 1909, survived by his wife and three minor daughters. In 1912, Henry Ernest Cooper bought the daughters' inherited rights from their legal guardian and petitioned to register Torrens title to all of Palmyra for himself. After a challenge in court, Cooper's ownership of the atoll was held by the Supreme Court of Hawaii to be subject to rights sold by Ringer's widow to Henry Maui and Joseph Clarke. Maui's and Clarke's interests, noted by the US Supreme Court in 1947, were divided one-third to Bella Jones of Honolulu in 1912[47] and the rest passed to their heirs.[44]

Cooper visited the island in July 1913 with scientists Charles Montague Cooke, Jr., and Joseph F. Rock, who wrote a scientific description of the atoll. Botanist Rock discovered unusual coconut palms in 1913, which palms expert Odoardo Beccari identified as Cocos nucifera palmyrensis (Becc.), the coconut type with the largest, longest and most triangular (in cross-section) fruits in the world, existing only at Palmyra. (The apparently closest Cocos nucifera relative occurs only in the distant Nicobar Islands in the Indian Ocean.)[13] The "mammoth coconuts" were put on display in Honolulu in 1914 along with paintings of Palmyra by Hawaiian artist D. Howard Hitchcock,[48] who had accompanied Cooper to the island.[49]

In September 1921, as part of a national push to better document the coastal and outlying areas owned by the United States, a small naval detachment was sent to Palmyra to conduct the first aerial surveys of the atoll. The events of that trip were recorded by a naval Pharmacist Mate, M. L. Steele, who wrote:

During our visit the weather was delightful. The detachment remained at these islands two days and they were perfect for flying, affording an opportunity to take wonderful aerial pictures. The commanding officer and the aviators made a number of flights and the official photographer was in his element.

At the time, Palmyra was occupied by three Americans: Colonel William Meng, his wife, and Edwin Benner, Jr.[50] While there, the USS Eagle Boat 40, which had transported aircraft and photographic equipment to the islands, made a very rare exception to naval regulation and took aboard the wife, Mrs. Meng, to return her to Honolulu for medical aid as she was not handling the isolation and trying physical conditions of Palmyra well.[51]

On August 19, 1922, Cooper sold his interest in the atoll except two minor islets to Leslie and Ellen Fullard-Leo for $15,000 (equivalent to $242,833 in 2021). They established the Palmyra Copra Company to harvest the coconuts growing on the atoll. Their three sons, including actor Leslie Vincent, continued as the owners afterwards, subject to a period of military administration and construction by the Navy before and during World War II from 1939 through 1945. In 2000, The Nature Conservancy acquired the majority of Palmyra Atoll from the Fullard-Leo family for $30 million (equivalent to $47,205,797 in 2021).[52]

U.S. Navy occupation (1939–1959)

A number of memoirs, reports and unofficial documents in the decades since World War II, have stated Palmyra was placed under naval jurisdiction in 1934, as part of Executive Order 6935.[53] However, Palmyra is not mentioned in this order, in any capacity. The first official mention of Palmyra under Naval Jurisdiction comes from a 1939 letter from the US Attorney General, mentioned in a 1997 Insular Areas report, concluding "Palmyra was U.S. public land and that the Fullard-Leo claim was invalid. S. Rep. No. 83-886 at 37."[54] Soon after this determination, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8616, officially, "Placing Palmyra Island, Territory of Hawaii, Under the Control and Jurisdiction of the Secretary of the Navy".[55]

Starting in 1937, the Fullard-Leo family began attempts to lease Palmyra to the U.S. Navy. During negotiations, the government filed a quiet title action against the Fullard-Leos and Henry Ernest Cooper's six surviving children, claiming property at Palmyra had never been privately owned under the Kingdom of Hawaii or later. The case reached the US Supreme Court. The Insular Areas report goes on to state, "While the suit was pending during World War II, the Navy occupied Palmyra and built a runway and several buildings." The Fullard-Leos and Coopers finally won their case in United States v. Fullard-Leo et al., 331 U.S. 256 (1947), which quieted good land title against the federal government in favor of private landowners. The opinion acknowledged certain of Henry Maui's and Joseph Clarke's interests (331 U.S. 256 at 278) but their heirs and their successor Mrs. Bella Jones were not made parties to the case.[56]As of 2007, descendants of Henry Cooper still owned two small Home islets in the southwestern tip that were not sold in 1922.[40]

In July 1938, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes wrote a letter to President Roosevelt, imploring him not to turn Palmyra over to the US Navy for use as a military base. Quoting his letter, he writes,

... the Navy Department has plans for the acquisition and development of the island as an air base. Our representatives have studied conditions at Palmyra and other islands in the south Pacific, and they report that use of this small land area as an air base for Navy Department purposes would undoubtedly destroy much, if not all, that makes the island one of our most scientifically and scenically unique possessions.

The letter was unsuccessful, and plans for the base proceeded.[57]

On February 14, 1941, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8682 to create naval defenses areas in the central Pacific territories. The proclamation established "Palmyra Island Naval Defensive Sea Area" which encompassed the territorial waters between the extreme high-water marks and the three-mile marine boundaries surrounding the atoll. "Palmyra Island Naval Airspace Reservation" was also established to restrict access to the airspace over the area. Only U.S. government ships and aircraft were permitted to enter the naval defense areas at Palmyra Atoll unless authorized by the Secretary of the Navy.

The Navy took over the atoll for use as the Palmyra Island Naval Air Station on August 15, 1941. From November 1939 through 1947, the atoll had resident Federal Government representatives, the island commanders. The atoll was shelled by a Japanese submarine in 1941, with no significant damage or injuries. The government made extensive alterations to the land forms. It blasted and dredged a ship channel from the open sea into the West Lagoon, which had been completely enclosed by islands and reef and was non-navigable until the channel reached the lagoon on May 15, 1941. It joined islands with causeway roads, built new islands and extended existing islands with dredged coral spoil, including the main runway on Cooper Island, an emergency landing strip called Sand Island joined by a causeway to Home Island, and two artificial runway islands that were not completed. These alterations blocked the water flow through the atoll and are believed to have severely harmed the natural ecology of the lagoons.[58]

During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy submarine I-75 bombarded the naval air station on December 24, 1941.[59][60] Opening fire at 04:55 Greenwich Civil Time, she fired twelve 120-millimeter (4.7 in) rounds from her deck gun, targeting the atoll's radio station, and hit the United States Army Corps of Engineers dredge Sacramento, which was anchored in the lagoon, with one shell.[60] A 5-inch (127 mm) coastal artillery battery on the atoll returned fire, forcing I-75 to submerge and withdraw.[60]

In the lobby of the "Transient Hotel" (built by the Seabees, and used by airmen on their way to the Pacific Theater front), a mural was hung depicting a quiet island scene. It was painted by Academy Award-nominated art director William Glasgow, who served in the Army from 1943 to 1945, though it is unclear when he painted it and how it ended up on Palmyra.[61]

After World War II, much of the Naval Air Station was demolished, with some of the materials piled up and burned on the atoll, dumped into the lagoon, or in the case of unexploded ordnance on some islets, left in place.[62]

U.S. Territory of Palmyra Island (1959–present)

When Hawaii was admitted to the United States in 1959, Palmyra was explicitly separated from the new state,[63] remaining a federal incorporated territory, to be administered by the secretary of the interior[40] under a presidential executive order.[64]

In 1962, the Department of Defense used Palmyra as an observation site during several high-altitude nuclear weapons tests high above Johnston Atoll. A group of about ten men supported the observation posts during this series of tests, while about 40 people carried out the observations.[65]

Alby Mangels, the Australian adventurer and documentary filmmaker of World Safari, visited the atoll during his six-year trip in the 1970s.[66]

In early 1979, the US government began exploring the idea of storing nuclear waste on remote Pacific islands, like Palmyra. Those who knew the island and the region saw no benefit to this idea, commenting on the devastating effects a leak of these storage tanks would create.[67] By 1982 a formal proposal had been written which "analyzes the proposal to store spent nuclear fuel on Palmyra Island, a US territory nearly a thousand miles south of Hawaii. The proposal has military, political, social, and technical implications."[68] The idea was abandoned soon after the proposal, and no such storage facilities were built.

Sea Wind murder

In 1974, Palmyra was the site of a murder, and possible double murder, of a wealthy San Diego couple, Malcolm "Mac" Graham and his wife, Eleanor "Muff" Graham.[69] The mysterious deaths, including the murder conviction of Duane ("Buck") Walker (a.k.a. Wesley G. Walker) for Eleanor Graham's murder, and the acquittal of his girlfriend, Stephanie Stearns, made headlines worldwide, and became the subject of a true crime book, And the Sea Will Tell, written by Bruce Henderson and Vincent Bugliosi, Stearns's defense attorney. The book led to a CBS television miniseries of the same name, starring James Brolin, Rachel Ward, Deidre Hall, and Hart Bochner; Richard Crenna played lawyer Bugliosi. The story was retold in The FBI Files.

Walker and Stearns were arrested in Honolulu in 1974 after returning from Palmyra aboard Sea Wind, the yacht stolen from the Grahams. Because no bodies were found at the time, Walker and Stearns were convicted only for the theft of the yacht. Six years later, a partially-buried, corroded chest was found in a lagoon at Palmyra, containing Eleanor Graham's remains. Walker and Stearns were arrested in Arizona for murder, and Walker was convicted in 1985. Stearns was acquitted in 1986 after her defense argued that Walker had committed the murders without Stearns's knowledge. Because no body or other evidence of Malcolm Graham's death has been discovered, his murder was never formally alleged.

Walker served 22 years in the United States Penitentiary, Victorville, California before receiving parole in 2007. He wrote an 895-page book about his experiences, and life on Palmyra Island, in which he denied killing Eleanor Graham. It states they had sexual relations, her husband Malcolm Graham caught them and shot at them in anger, inadvertently killing her. The two men had a gunfight the next day, and Malcolm Graham consequently died from a rifle wound.

Walker accused author Vincent Bugliosi – Stearns' lawyer – of vainglory and exploiting class prejudice against him, and wrote that his own lawyer Earle Partington was incompetent. Walker did not implicate Stearns in any killing.[70] Walker died in a nursing home, on April 26, 2010, following a stroke.[69]

Sovereignty challenges (1997–1999)

In the late 1990s, Rachel Lahela Kekoa Bolt, a native Hawaiian heir of Henry Maui, and some of her descendants filed federal lawsuits claiming her inherited interest in Palmyra and challenging the legality of the Newlands Resolution that annexed Hawaii. The lawsuits challenged American sovereignty over both the State of Hawaii and the United States Territory of Palmyra Island.[71][72] On similar grounds they intervened in a federal marine salvage claim for a sunken treasure ship at Palmyra.[35] The cases were dismissed on procedural grounds before trial.

National Wildlife Refuge and National Monument

In December 2000, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) bought most of Palmyra Atoll from the three Fullard-Leo brothers[40] for coral reef conservation and research. In 2003, a scientific study was published about fossilized coral that was washing up on Palmyra. This fossilized coral was examined for evidence of the behavior of the effect of El Niño on the tropical Pacific Ocean over the past 1,000 years.[73]

On January 18, 2001, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt issued Secretary's Order No. 3224 designating Palmyra's tidal lands, submerged lands and surrounding waters out to 12 nautical miles (22 km) from the water's edge as a National Wildlife Refuge. Subsequently, the Department of the Interior published a regulation providing for the management of the refuge. 66 Fed. Reg. 7660-01 (January 24, 2001). The pertinent part of the regulation states:

We will close the refuge to commercial fishing but will permit a low level of compatible recreational fishing for bonefishing and deep water sportfishing under programs that we will carefully manage to ensure compatibility with refuge purposes. ... Management actions will include protection of the refuge waters and wildlife from commercial fishing activities.

In March 2003, TNC conveyed 416 acres (1.68 km2) of the emergent land of Palmyra to the United States to be included in the refuge. In 2005, it added 28 acres to the conveyance. TNC and Henry Ernest Cooper's descendants kept their remaining private land tracts.

The conveyance to TNC from the Fullard-Leos in 2000 was subject to a preexisting commercial fishing licence. Then in 2001 the Secretary of the Interior banned commercial fishing near Palmyra but allowed sport fishing, as quoted above. In January 2007, the commercial fishing licensees sued the United States in the Court of Federal Claims alleging that, under the Takings Clause, the Interior Department regulation had "directly confiscated, taken, and rendered wholly and completely worthless" their purported property interests. The United States filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit, and the court granted the motion.[74] On April 9, 2009, the court's decision was affirmed by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.[75]

In November 2005, TNC established a new research station on Palmyra to study global warming, coral reefs, invasive species and other environmental concerns.[76]

The Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, comprising Palmyra Atoll, Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, and Kingman Reef, was established on January 6, 2009, by proclamation of President George W. Bush. This national monument extends 50 nautical miles (93 kilometers) offshore and is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service[11] and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.[77]

Conservation and restoration

In 2011, Fish and Wildlife Service, TNC and Island Conservation began an extensive program to eradicate the horde of non-native rats that had arrived on Palmyra during World War II. As many as 30,000 rats once roamed the atoll, eating the eggs of native seabirds and destroying the seedlings of one of the largest remaining Pacific stands of pisonia grandis trees. The rats were eliminated in 2012; however, fifty-one animal samples representing 15 species of birds, fish, reptiles and invertebrates were collected for residue analysis during systematic searches or as nontarget mortalities. Brodifacoum residues (the toxicant employed during the project) were detected in most (84.3%) of the samples analyzed with unknown long-term and sublethal effects.[78][79][80] One side effect was the demise of the island's population of Asian tiger mosquitoes. This was claimed to be the first time that killing off one unwanted species resulted in the removal of a second unwanted species. The other mosquito species on the island, Culex quinquefasciatus, has a preference for feeding on birds and was not affected by the elimination of rats.[81][82]

Post-rat-eradication monitoring documented a notable recruitment event for pisonia grandis, a dominant tree species that is important throughout the Pacific region.[83] However, by five years post-eradication, a 13-fold increase in recruitment of the range-expanding coconut palm Cocos nucifera was found.[84]

Beginning in 2019, TNC worked in partnership with Island Conservation and the Fish and Wildlife Service to restore the native rainforest at Palmyra Atoll by removing dominant C. nucifera coconut palms, which the conservancy says are the result of former copra plantations and military activity. Other trees provide habitat for 11 seabird species, and the conservancy wrote that their re-establishment across the atoll would encourage coral growth and might lessen the local impact of a rise in sea-level. As of December 2019, half a million coconut sprouts had been removed, and tracking begun of the ecosystem's response.[85]

Palmyra Atoll's location in the Pacific Ocean, where the southern and northern currents meet, litters its beaches with trash and debris. Plastic mooring buoys and plastic bottles are plentiful.[86]

Tourism

Tourists are allowed to visit Palmyra Atoll (unlike most of the U.S. minor outlying islands, which are closed to the public). Palmyra Atoll is difficult to access, and few visit. Visitors must obtain prior approval from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or The Nature Conservancy.[87] A statement by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is as follows:

"Public access to Palmyra Atoll is self-limiting due to the very high expense of traveling to such a remote destination. The Nature Conservancy owns and operates the only airplane runway on Palmyra, and by boat it's a 5–7 day sailing trip from Honolulu. There are four ways the public may gain access to the refuge: (1) Working for, contracting with, or volunteering for The Nature Conservancy or Fish and Wildlife Service; (2) Conducting scientific research via Fish and Wildlife Service Special Use Permits; (3) Invitation through The Nature Conservancy sponsored donor trip; (4) Visitation by private recreational sailboat or motorboat."[87]

Amateur radio (DX) visitors

Since the 1940s, Palmyra's most consistent visitors have been members of distance expedition (DX) teams, as the atoll is a popular spot for these amateur radio operators. To date, more than 25 expeditions have arrived. Once on the islands, the hams set up radios and antennas and make as many two-way radio contacts with other hams as possible. Former N. California DX Club president Richard Malcolm Crouch became a Palmyra landowner.[88]

In June 1974 the KP6PA DXpedition team helped rescue a couple whose ship had run aground on the reefs. The man, Buck Walker, was later convicted of homicide in the much publicized Sea Wind murder case.[89] Two members of the 1980 team were injured severely enough to need an airlift back to Honolulu. The first incident resulted from injuries sustained in a plane crash as their pilot underestimated wind conditions and the poor state of the landing strip. The second injury, to a surgeon, happened when he fell and cut his hands on broken glass. The surgeon then sued the atoll's owners, as he was no longer able to practice surgery, and the atoll was closed to visitors for most of the 1980s while cleanup activities were undertaken.[90]

See also

- List of Guano Island claims

References

- "Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- Rauzon, Mark J. (2016). Isles of Amnesia: The History, Geography, and Restoration of America's Forgotten Pacific Islands. University of Hawai'i Press, Latitude 20. Pages 85–86. ISBN 9780824846794.

- Sterling, Eleanor (July 28, 2010). "In the Middle of Nowhere, Snooping on Sea Turtles". New York Times. Scientist at Work blog. Retrieved September 28, 2010.

- Unattributed. "The Consortium". palmyraresearch.org. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- Per U.S. Code Title 48: Territories and Insular Possessions

- "Rose Atoll Marine National Monument". Noaa.gov. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- "American Samoa". American Samoa | Culture, History, & People. Britannica.com. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- "Climate: Palmyra Atoll". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- "Report". The Naval Chronicle. Vol. XII. 1804. pp. 464–465. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- "Public Law 86–624" (PDF). July 12, 1960. p. 424 (14). Retrieved January 5, 2014.

shall be exercised in such manner and through such agency or agencies as the President of the United States may direct or authorize.

- "Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument". fws.gov. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- Secretary of the Interior Order No. 2862, Palmyra Island Land Recordation, March 19, 1962, F. R. Doc. 62-2736.

- Joseph F. Rock (April 1916). "Palmyra Island with a Description of its Flora". Bulletin Number 4. College of Hawaii.

- "Australia – Oceania :: United States Pacific Island Wildlife Refuges — The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- 19 CFR 101.1

- 19 CFR 7.2

- In the Matter of the Application of Henry E. Cooper to Register and Confirm Title to Palmyra Island, Application No. 223, Hawaii Court of Land Registration (1912).

- FAA Airport Form 5010 for P16 PDF, effective 2007-08-30

- "Palmyra Atoll". Office of Insular Affairs web site. United States Department of Interior. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- "VMFA-211 history". 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1982) [1969]. Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II (PDF) (reprint ed.). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-405-12194-6. LCCN 70605402. OCLC 72556.

- Freeman, Paul. "Abandoned and Little-Known Airfields: Western Pacific Islands". airfields-freeman.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- Airnav.com – PLPA / Palmyra Atoll Airfield, page retrieved 21 November 2013.

- Edmund Fanning (1924). Voyages and Discoveries in the South Seas 1792–1832. Salem, Massachusetts: Marine Research Society. pp. 163–167.

- Thomas, H.F., "Premonition of Danger" in "Connecticut Circle". Fate, March 1953; see also Gaddis, Vincent H. Invisible Horizons Ace Books, Inc., 1965.

- H. E. Maude (1961). "Post-Spanish discoveries in the central Pacific". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 70 (1): 67. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- Dehner, Steve (April 2019). "The Armchair Navigator I".

- Howay, F.W. (October 1933). "Captain Cornelius Sowle on the Pacific Ocean". The Washington Historical Quarterly. University of Washington. 24 (4): 243–249. JSTOR 40475540.

- Brainard, Russell E.; et al. (2019). "Coral Reef Ecosystem Monitoring Report for the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument 2000–2017, Chapter 2: Palmyra Atoll" (PDF). PIFSC Special Publication. Washington, D.C.: NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Admin., U.S. Dept. of Commerce. p. 11. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- Capt. Sawle, Palmyra (September 6, 1806). "Letter to the Editor". Aurora for the Country. Philadelphia.

- Chadwick, Alex (2001). "The Treasured Islands of Palmyra". NationalGeographic.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- Connor, Martin (April 14, 1923). "Priceless Treasures of the Incas May Be Buried on Island in Palmyras". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- Walker, Capt. F. D. (July 6, 1903). "Honolulu Man Knows Where Much Silver has been Buried". Daily Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- Walker, Capt. F. D. (1914). "Pirates' Buried Bullion May Be Found on Palmyra". New York Sun. New York. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- William A. Warren v. Unidentified Wrecked Vessel, Case No. CV96-00018SPK (D.C. Hawaii 1998).

- London, Jack (June 24, 1911). "The Proud Goat of Aloysius Pankburn". Saturday Evening Post. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "Judge Cooper Off for Pirates' Treasure Isle of Palmyra". Honolulu Star Advertiser. June 29, 1911. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "United States Exploring Expedition Vol XXIII: Hydrography". 1842. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- Rauzon, Mark J. (2016). Isles of Amnesia: The History, Geography, and Restoration of America's Forgotten Pacific Islands. University of Hawai'i Press, Latitude 20. Page 88. ISBN 9780824846794.

- "Department of the Interior, Office of Insular Affairs". Archived from the original on October 31, 2007. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- Estate of Kalama, Probate (Circuit Court, Honolulu 1878–1885).

- "Palmyra Island". The Evening Bulletin. Honolulu. August 14, 1897. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- United States v. Fullard Leo et al., 66 F.Supp. 774 (1940).

- "Contest Cooper's Claim to Palmyra". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. May 3, 1912. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- "Has Prior Claim: Palmyra Claimed by Kamehameha". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. August 13, 1897. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- "Palmyra Title May Now be Tested: Sale of Fanning Brings the Little Hawaiian-Owned Group into Prominence". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. January 16, 1912. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- Application No. 223 of Henry E. Cooper, Document No. 468, Hawaii Court of Land Registration (1912).

- "Personal Mention". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu. May 28, 1914. p. 4. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- "Judge Cooper Is Enthusiastic; In Regard Palmyra". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu. April 23, 1914. p. 4. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- Morris, Penrose Clibborn (1933). "How the Territory of Hawaii Grew and What Domain It Covers," Forty-Second Annual Report of the Hawaiian Historical Society for the Year 1933, p. 25. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- M.L. Steele (January 1922). "The Palmyra Islands". Hospital Corps Quarterly. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- "Palmyra: A Colorful History". The Nature Conservancy. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "Executive Order 6935". U.S. Government. December 29, 1934.

- "US Insular Areas Report". U.S. Government. November 1, 1997. Archived from the original on August 21, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- "Executive Order 8616". U.S. Government. December 19, 1940. Archived from the original on August 21, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- "GAO/OGC-98-5 – U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution". U.S. Government Printing Office. November 7, 1997. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- Ickes, Harold (July 11, 1938). "MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT REGARDING PALMYRA ISLAND". Office of the Secretary of the Interior. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- Collen, J. D.; Garton, D. W.; Gardner, J. P. A. (2000). "Shoreline Changes and Sediment Redistribution at Palmyra Atoll (Equatorial Pacific Ocean): 1874–Present". Journal of Coastal Research. 25:3: 711–722. doi:10.2112/08-1007.1. S2CID 129960273.

- I-175 ijnsubsite.com November 25, 2018 Accessed 6 May 2022

- Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander (June 12, 2010). "IJN Submarine I-175: Tabular Record of Movement". combinedfleet.com. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- 76th Navy CMBU (1945). "Palmyra Island". 76th Naval Construction Battalion Yearbook. p. 4. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017 – via Palmyra Archive.

- "Palmyra Atoll: WWII Naval Air Station Contaminant Impacts on Terrestrial and Marine Ecosystems within the USFWS National Wildlife Refuge". www.cerc.usgs.gov. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "Little Palmyra Atoll Isn't Celebrating". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Daytona Beach. March 14, 1959. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- "ADMINISTRATION OF PALMYRA ISLAND". Executive Order No. 10967 (text). October 10, 1961. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- "6th Weather Squadron During Project Dominic". Palmyra Atoll Digital Archive. 1962. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- "Alby Mangels World Safari visits the Palmyra Atoll". Palmyra Atoll Digital Archive. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- "Palmyra Pushed into the Nuclear Age". The Honolulu Advertiser. 1979. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- "National Policy Implications of Storing Nuclear Waste in the Pacific Region". National Defense University. March 12, 1982. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- Scott, Susan (14 June 2010). "Palmyra's scads of rats rival its crabs and birds". Honolulu Star Advertiser. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Walker, Wesley (2007). Palmyra: the True Story of an Island Tragedy. Incline Village, Nevada: B. & E. Press.

- Painter et al. v. United States et al., Case No. CV96-00685HG (D.C. Hawaii 1998).

- Painter v. United States et al., Case No. 1:98 CV-01737 (D.C. Dist.Col. 1999).

- K. M. Cobb et al., El Niño/Southern Oscillation and Tropic Pacific Climate During the Last Millennium, Nature, Vol. 424, July 17, 2003

- Palmyra Pacific Seafoods, L.L.C. v. United States, 80 Fed. Cl. 228 (U.S. Court of Federal Claims 2008).

- Palmyra Pacific Seafoods, L.L.C. v. United States, 561 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

- "Opening of The Nature Conservancy Research Station on Palmyra Atoll". Hawai'i Post. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "Discovering the Deep: Exploring Remote Pacific MPAs: Background: Conservation and Research Initiatives at Palmyra Atoll and Kingman Reef: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research". oceanexplorer.noaa.gov. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- "Palmyra Atoll Restoration Project". Island Conservation. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Pitt, W.C.; Berentsen, A.R.; Volker, S.F.; Eisemann, J.D. (September 2012). "Palmyra Atoll Rainforest Restoration Project: Monitoring Results for the Application of Broadcast of Brodifacoum 25W: Conservation to Eradicate Rats" (PDF). QA-1875 Final Report. Hilo, Hawaii: USDA, APHIS, W, NWRC. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 3, 2014. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- "Native species expected to rebound on rat-free Palmyra Atoll". Saipan Tribune (Press release). February 7, 2013. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- "Disappearing Mosquitoes Leave Clues About Basic Ecology". Island Conservation. March 1, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- TenBruggencate, Jan (March 14, 2018). "When Rats Were Wiped Out On This Island, So Were The Mosquitoes". Honolulu Civil Beat. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- "Study Shows 5000% Increase in Native Trees on Rat-free Palmyra Atoll". Island Conservation. July 17, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Bosso, Luciano; Wolf, Coral A.; Young, Hillary S.; Zilliacus, Kelly M.; Wegmann, Alexander S.; McKown, Matthew; Holmes, Nick D.; Tershy, Bernie R.; Dirzo, Rodolfo; Kropidlowski, Stefan; Croll, Donald A. (2018). "Invasive rat eradication strongly impacts plant recruitment on a tropical atoll" (PDF). PLOS ONE. 13 (7): e0200743. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1300743W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200743. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6049951. PMID 30016347.

- "Palmyra Resilience". The Nature Conservancy. December 2019. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Smith, Harry (May 12, 2016). "On Assignment: The Last Best Place On Earth" (Video). Dateline NBC. NBC News. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Palmyra Atoll – Plan Your Visit". fws.gov. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Palmyra Atoll – Plan Your Visit". fws.gov. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved January 7, 2019. - Palmyra Island Land Recordation Document No. 93, U.S. District Court for the District of Hawaii, Honolulu, 2015.

- "Muff and Mac Graham Murders: How Did Buck Duane Walker Die? Where is Stephanie Stearns Now?". The Cinemaholic. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- Betty Fullard-Leo (January 1984). "The Perils of Palmyra". Honolulu Magazine. Archived from the original on March 31, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

Further reading

- Vincent Bugliosi and Bruce B. Henderson (1991/1992), And the Sea Will Tell, reprint, New York: Ballantine Books.

External links

- Palmyra Atoll photo gallery by FWS

.svg.png.webp)