Pauli Murray

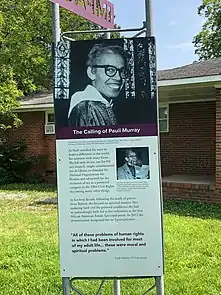

Anna Pauline "Pauli" Murray (November 20, 1910 – July 1, 1985) was an American civil rights activist who became a lawyer, gender equality advocate, Episcopal priest, and author. Drawn to the ministry, in 1977 she became one of the first women—and the first African-American woman—to be ordained as an Episcopal priest.[3][4]

The Reverend Pauli Murray | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Anna Pauline Murray November 20, 1910 |

| Died | July 1, 1985 (aged 74) Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Partner | Renee Barlow (deceased 1973) |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 1 July |

| Venerated in | Episcopal Church (United States) |

| Church | Episcopal Church (United States) |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1976 (deacon) 1977 (priest) |

| Personal details | |

| Denomination | Christianity (Anglican) |

| Academic background | |

| Education | City University of New York, Hunter (BA) Howard University (LLB) University of California, Berkeley (LLM) Yale University (SJD) General Theological Seminary (MDiv) |

| Influences | Mary Daly[1] J. Deotis Roberts[1] Rosemary Radford Ruether[1] Letty M. Russell[1] |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | American studies |

| Institutions | Ghana School of Law Brandeis University |

| Influenced | Patricia Hill Collins Marian Wright Edelman[2] Ruth Bader Ginsburg[2] Eleanor Holmes Norton[2] Eleanor Roosevelt[2] |

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Murray was essentially orphaned, raised mostly by her maternal aunt in Durham, North Carolina. At the age of 16, she moved to New York City to attend Hunter College, and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English in 1933. In 1940, Murray sat in the whites-only section of a Virginia bus with a friend, and they were arrested for violating state segregation laws.[5] This incident, and her subsequent involvement with the socialist Workers' Defense League, led her to pursue her career goal of working as a civil rights lawyer. She enrolled in the law school at Howard University, where she was the only woman in her class.[6] Murray graduated first in her class, but she was denied the chance to do post-graduate work at Harvard University because of her gender. She called such prejudice against women "Jane Crow", alluding to the Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation in the Southern United States. She earned a master's degree in law at University of California, Berkeley, and in 1965 she became the first African American to receive a Doctor of Juridical Science degree from Yale Law School.

As a lawyer, Murray argued for civil rights and women's rights. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Chief Counsel Thurgood Marshall called Murray's 1950 book, States' Laws on Race and Color, the "bible" of the civil rights movement.[4][7] Murray was appointed by President John F. Kennedy to serve on the 1961–1963 Presidential Commission on the Status of Women.[8] In 1966, she was a co-founder of the National Organization for Women. Ruth Bader Ginsburg named Murray as a coauthor of the ACLU brief in the landmark 1971 Supreme Court case Reed v. Reed, in recognition of her pioneering work on gender discrimination. This case articulated the "failure of the courts to recognize sex discrimination for what it is and its common features with other types of arbitrary discrimination."[8] Murray held faculty or administrative positions at the Ghana School of Law, Benedict College, and Brandeis University.

In 1973, Murray left academia for activities associated with the Episcopal Church. She became an ordained priest in 1977, among the first generation of women priests. In addition to her legal and advocacy work, Murray published two well-reviewed autobiographies and a volume of poetry. Her volume of poetry, Dark Testament (1970), was republished in 2018.

Murray struggled in her adult life with issues related to her sexual and gender identity, describing herself as having an "inverted sex instinct". She had a brief, annulled marriage to a man and several deep relationships with women. In her younger years, she occasionally had passed as a teenage boy.[9] A number of scholars, including a 2017 biographer, have retroactively classified Murray as transgender.[4]

Early life

Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on November 20, 1910.[10] Both sides of her family were of mixed racial origins, with ancestors including Black slaves, white slave owners, Native Americans, Irish, and free Black people. The varied features and complexions of her family were described as a "United Nations in miniature".[11] Murray's parents, schoolteacher William H. Murray and nurse Agnes (Fitzgerald) Murray, both identified as Black.[12] In 1914, Agnes died of a cerebral hemorrhage when her daughter was three.[13] After Murray's father began to have emotional problems, some think as a result of typhoid fever, relatives took custody of his children.

Three-year-old Pauli Murray was sent to Durham, North Carolina, to live with her mother's family.[14] There, she was raised by her maternal aunts, Sarah (Sallie) Fitzgerald and Pauline Fitzgerald Dame (both teachers), as well as her maternal grandparents, Robert and Cornelia (Smith) Fitzgerald.[15] She attended St. Titus Episcopal Church with her mother's family, as had her mother before Murray was born.[16] When she was twelve, her father was committed to the Crownsville State Hospital for the Negro Insane, where he received no meaningful treatment. Pauli had wanted to rescue him, but in 1923 (when she was thirteen), he was bludgeoned to death by a white guard with a baseball bat.[4]

Murray lived in Durham until the age of 16, at which point she moved to New York to finish high school and prepare for college.[17] There she lived with the family of her cousin Maude. The family was passing for white in their white neighborhood. Murray's presence discomfited Maude's neighbors, however, as Murray was more visibly of partial African descent.[18] She graduated with her second high school diploma and honors from Richmond Hill High School in 1927, and enrolled at Hunter College for two years.[19]

Murray married William Roy Wynn, known as Billy Wynn, in secret on November 30, 1930, but soon came to regret the decision.[20] The historian Rosalind Rosenberg wrote:

Their honeymoon weekend, spent in a "cheap West Side Hotel", was a disaster, an experience that she later attributed to their youth and poverty. The truth was more complicated. As Pauli explained in notes to herself a few years later, she had felt repelled by the act of sexual intercourse. Part of her had wanted to be a "normal" woman, but another part resisted. "Why is it when men try to make love to me, something in me fights?" she wondered.[21]

Murray and Wynn only spent a few months together before both leaving town.[21] They did not see one another again before Murray contacted him to have their marriage annulled on March 26, 1949.[22]

Inspired to attend Columbia University by a favorite teacher, Murray was turned away from applying because the university did not admit women, and she did not have the funds to attend its women's coordinate college, Barnard College.[23] Instead she attended Hunter College, a free women's college of City University of New York, where she was one of the few students of color.[24] Murray was encouraged in her writing by one of her English instructors, from whom she earned an "A" for an essay about her maternal grandfather. This became the basis of her later memoir Proud Shoes (1956), about her mother's family. Murray published an article and several poems in the college paper. She graduated in 1933 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English.[23]

Murray further continued her education in New York City at Jay Lovestone's New Workers School on West 33rd Street, taking, in Rosenberg's words, "night classes with Lovestone and others ... including Marxist Philosophy, Historical Materialism, Marxian Economics, and Problems of Communist Organization."[25]

Jobs were difficult to find during the Great Depression. Murray took a job selling subscriptions to Opportunity, an academic journal of the National Urban League, a civil rights organization based in New York City. Poor health forced her to resign, and her doctor recommended that Murray seek a healthier environment.[26]

Murray took a position at Camp Tera, a "She-She-She" conservation camp. Established at the urging of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, these federally-funded camps paralleled the all-male Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps formed under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal to provide employment to young adults while improving national infrastructure.[27][28] During her three months at the camp, Murray's health recovered. She also met Eleanor Roosevelt. Later they had correspondence that affected both of them. Murray clashed with the camp's director, however. The director had found a Marxist book from a Hunter College course among Murray's belongings, and questioned Murray's attitude during the First Lady's visit. The camp director also disapproved of Murray's cross-racial relationship with Peg Holmes, a white counselor.[29] Murray and Holmes left the camp in February 1935, and began traveling the country by walking, hitchhiking, and hopping freight trains.[30]

Murray later worked for the Young Women's Christian Association.[31]

1938-1945: Early activism and law school

Murray applied to PhD program in sociology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill in 1938, but was rejected because of her race.[32] All schools and other public facilities in the state were segregated by state law, as was the case across the South.[23] The case was broadly publicized in both white and black newspapers. Murray wrote to officials ranging from the university president to President Roosevelt, releasing their responses to the media in an attempt to embarrass them into action. The NAACP initially was interested in the case, but later declined to represent her in court, perhaps fearing that her long residence in New York state weakened her case.[33] NAACP leader Roy Wilkins opposed representing her because Murray had already released her correspondence, which he considered "not diplomatic".[34] Concerns about her sexuality also may have played a role in the decision;[35] Murray often wore pants rather than the customary skirts of women and was open about her relationships with women.[36]

In early 1940, Murray was walking the streets in Rhode Island, distraught after "the disappearance of a woman friend". She was taken into custody by police.[37][lower-alpha 1] She was transferred to Bellevue Hospital in New York City for psychiatric treatment.[37] In March, Murray left the hospital with Adelene McBean, her roommate and girlfriend,[38] and took a bus to Durham to visit her aunts.

In Petersburg, Virginia, the two women moved out of broken seats in the black (and back) section of the bus, where state segregation laws mandated they sit, and into the white section. Inspired by a conversation they had been having about Gandhian civil disobedience, the two women refused to return to the rear even after the police were called. They were arrested and jailed.[39] Murray and McBean initially were defended by the NAACP, but when the pair were convicted only of disorderly conduct rather than violating segregation laws, the organization ceased to represent them.[40] The Workers' Defense League (WDL), a socialist labor rights organization that also was beginning to take civil rights cases, paid her fine. A few months later the WDL hired Murray for its administrative committee.[41]

With the WDL, Murray became active in the case of Odell Waller, a black Virginia sharecropper sentenced to death for killing his white landlord, Oscar Davis, during an argument. The WDL argued that Davis had cheated Waller in a settlement and as their argument grew more heated, Waller had shot Davis in legitimate fear of his life.[42] Murray toured the country raising funds for Waller's appeal.[43] She wrote to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt on Waller's behalf.[44] Roosevelt in turn wrote to Virginia Governor Colgate Darden, asking him to guarantee that the trial was fair; she later persuaded the president to privately request Darden to commute the death sentence.[45] Through this correspondence, Murray and Eleanor Roosevelt began a friendship that would last until the latter's death two decades later.[46] Despite the efforts of the WDL and the Roosevelts, however, the governor did not commute Waller's sentence. Waller was executed on July 2, 1942.[47]

Howard and Berkeley

Murray's trial on charges stemming from the bus incident and her experience with the Waller case inspired a career in civil rights law.[48] In 1941, she began attending Howard University law school. Murray was the only woman in her law school class, and she became aware of sexism at the school, which she labeled "Jane Crow"—alluding to Jim Crow, the system of racial discriminatory state laws oppressing African Americans.[49] On Murray's first day of class, one professor, William Robert Ming, remarked that he did not know why women went to law school. She was infuriated.[50]

In 1942, while still in law school, Murray joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). That year she published an article, "Negro Youth's Dilemma", that challenged segregation in the US military, which continued during the Second World War. She also participated in sit-ins challenging several Washington, DC, restaurants with discriminatory seating policies. These activities preceded the more widespread sit-ins during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.[31]

Murray was elected chief justice of the Howard Court of Peers, the highest student position at Howard, and in 1944 she graduated first in her class.[51] Traditionally, Howard's top graduate received a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship for graduate work at Harvard University, but Harvard Law did not accept women at that time. Murray was thus rejected, despite a letter of support from sitting President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[31] Murray wrote in response, "I would gladly change my sex to meet your requirements, but since the way to such change has not been revealed to me, I have no recourse but to appeal to you to change your minds. Are you to tell me that one is as difficult as the other?"[52]

Excluded from Harvard, Murray undertook post-graduate work at the School of Law at the University of California, Berkeley.[31] Her master's degree thesis was entitled "The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment", which argued that "the right to work is an inalienable right". It was published in Berkeley Law's flagship California Law Review.[53]

Professional career

After passing the California bar exam in 1945, Murray was hired as the state's first black deputy attorney general in January of the following year.[54] That year, the National Council of Negro Women named her its "Woman of the Year" and Mademoiselle magazine did the same in 1947.[7] Murray was the first Black woman hired as an associate attorney at the Paul, Weiss law firm in New York City, working there from 1956 to 1960. Murray was the firm's second Black associate after Bill Coleman. She first met Ruth Bader Ginsburg at Paul, Weiss, when Ginsburg was briefly a summer associate there.[55]

Activism against racial and sex discrimination

Murray was an outspoken activist at the forefront of the civil rights movement, alongside such leaders as Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. She coined the term Jane Crow, which demonstrated Murray's belief that Jim Crow laws also negatively affected African-American women. She was determined to work with other activists to put a halt to both racism and sexism. Murray's speech, "Jim Crow and Jane Crow", delivered in Washington, DC, in 1964, sheds light on the long struggle of African-American women for racial equality and their later fight for equality among the sexes. As she put it, "Not only have they stood ... with Negro men in every phase of the battle, but they have also continued to stand when their men were destroyed by it." The black women decided to "...continue ... [standing] ..." for their freedom and liberty even when "...their men ..." began to experience exhaustion from a long struggle for civil rights. These women were unafraid to stand up for what they believed in and refused to back down from the long and tedious "battle". Murray continued her praise for black women when she stated that "...one cannot help asking: would the Negro struggle have come this far without the indomitable determination of its women?" The "Negro struggle" was able to progress partly because of "...the indomitable determination of its women."[56]

In 1950, Murray published States' Laws on Race and Color, an examination and critique of state segregation laws throughout the nation. She drew on psychological and sociological evidence as well as legal, an innovative discussion technique for which she had previously been criticized by Howard professors. Murray argued for civil rights lawyers to challenge state segregation laws as unconstitutional directly, rather than trying to prove the inequality of so-called "separate but equal" facilities, as was argued in some challenges.[31] Thurgood Marshall, then NAACP chief counsel and a future supreme court justice, called Murray's book the "bible" of the civil rights movement.[7] Her approach was influential to the NAACP arguments in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), by which they drew from psychological studies assessing the effects of segregation on students in school. The US Supreme Court ruled that segregated public schools were unconstitutional.

In 1961, US President John F. Kennedy appointed Murray to the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. She prepared a memo entitled "A Proposal to Reexamine the Applicability of the Fourteenth Amendment to State Laws and Practices Which Discriminate on the Basis of Sex Per Se", which argued that the Fourteenth Amendment forbade sex discrimination as well as racial discrimination.[31]

In 1963, she became one of the first to criticize the sexism of the civil rights movement, in her speech "The Negro Woman in the Quest for Equality".[57] In a letter to civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph, she criticized the fact that in the 1963 March on Washington no women were invited to make one of the major speeches or to be part of its delegation of leaders who went to the White House, among other grievances. She wrote:

I have been increasingly perturbed over the blatant disparity between the major role which Negro women have played and are playing in the crucial grassroots levels of our struggle and the minor role of leadership they have been assigned in the national policy-making decisions. It is indefensible to call a national march on Washington and send out a call which contains the name of not a single woman leader.[58]

In 1964, Murray wrote an influential legal memorandum in support of the National Women's Party's successful effort (led by Alice Paul) to add "sex" as a protected category in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[59] In 1965, Murray published her landmark article (coauthored by Mary Eastwood), "Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII", in the George Washington Law Review. The article discussed Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as it applied to women, and drew comparisons between discriminatory laws against women and Jim Crow laws.[60] The memo was shared with every member of Congress and Lady Bird Johnson, then First Lady, who brought it to President Lyndon B. Johnson's attention.[55]

In 1966, she was a cofounder of the National Organization for Women (NOW), which she hoped could act as an NAACP for women's rights.[31] In March of that year, Murray wrote to Commissioner Richard Alton Graham that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission was not fulfilling its duty in upholding the gendered portion of its mission, leaving only half the black population protected.[61] Later in 1966, she and Dorothy Kenyon of the ACLU successfully argued White v. Crook, a case in which a three-judge court of the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama ruled that women have an equal right to serve on juries.[62] When future Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then with the ACLU, wrote her brief for Reed v. Reed, the 1971 Supreme Court case that extended the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause to women for the first time, she added Murray and Kenyon as coauthors in recognition of her debt to their work.[8]

Academia

Murray lived in Ghana from 1960 to 1961, serving on the faculty of the Ghana School of Law.[31] She returned to the US and studied at Yale Law School, in 1965 becoming the first African American to receive a Doctor of Juridical Science degree from the school.[63] Her dissertation was titled, "Roots of the Racial Crisis: Prologue to Policy".[64]

Murray served as vice president of Benedict College from 1967 to 1968. She left Benedict to become a professor at Brandeis University.[7] She taught at Brandeis from 1968 to 1973, receiving tenure in 1971 as a full professor in American studies and appointed as Louis Stulberg Chair in Law and Politics.[65] In addition to teaching law, Murray introduced classes on African-American studies and women's studies, both firsts for the university. Murray later wrote that her time at Brandeis was "the most exciting, tormenting, satisfying, embattled, frustrated, and at times triumphant period of my secular career".[66]

Priesthood

Increasingly inspired by her connections with other women in the Episcopal Church, Murray, then more than sixty years old, left Brandeis to attend General Theological Seminary, where she received a Master of Divinity in 1976 with her thesis, "Black Theology and Feminist Theology: A Comparative Review", spending the final year and a half of her course at Virginia Theological Seminary.[67][68][69][31] She was ordained to the diaconate in 1976[70] and, after three years of study, in 1977 she became the first African-American woman ordained as an Episcopal priest and was among the first generation of Episcopal women priests.[17] That year she celebrated her first Eucharist by invitation and preached her first sermon at Chapel of the Cross. That was the first time a woman celebrated the Eucharist at an Episcopal church in North Carolina. In 1978, she preached in her home town of Durham, North Carolina, on Mother's Day at St. Philip's Episcopal Church, where her mother and grandparents had attended in the 19th century. She announced her mission of reconciliation.[16] For the next seven years, Murray worked in a parish in Washington, DC, focusing particularly on ministry to the sick.[31]

Death and legacy

On July 1, 1985, Pauli Murray died of pancreatic cancer in the house she owned with lifelong friend Maida Springer Kemp in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[7][71]

In 2012, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church voted to honor Murray as one of its Holy Women, Holy Men,[72] to be commemorated on July 1, the anniversary of her death, along with fellow writer Harriet Beecher Stowe.[73] Bishop Michael Curry of the Diocese of North Carolina said this recognition honors "people whose lives have exemplified what it means to follow in the footsteps of Jesus and make a difference in the world."[74]

In 2015, the National Trust for Historic Preservation designated the childhood home of Murray (on Carroll Street in Durham, North Carolina's West End neighborhood) as a National Treasure.[75]

In April 2016, Yale University announced that it had selected Murray as the namesake of one of two new residential colleges (Pauli Murray College) to be completed in 2017; the other was to be named after Benjamin Franklin.[76]

In December 2016, the Pauli Murray Family Home was designated as a National Historic Landmark by the US Department of Interior.[77]

In 2018, Murray was chosen by the National Women's History Project as one of its honorees for Women's History Month in the United States.[78]

Also in 2018, Murray was made a permanent part of the Episcopal Church's calendar of saints (she is commemorated on July 1). Thurgood Marshall and Florence Li Tim-Oi were also added permanently to the calendar.[79]

In January 2021, a biographical documentary entitled My Name Is Pauli Murray premiered at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival.[80][81]

Sexuality and gender identity

Murray struggled with her sexual and gender identity through much of her life. Her marriage as a teenager ended almost immediately with the realization that "when men try to make love to me, something in me fights".[82] Although acknowledging the term "homosexual" in describing others, Murray preferred to describe herself as having an "inverted sex instinct" that caused her to behave as a man would when attracted to women. She wanted a "monogamous married life", but one in which she was the man.[83] The majority of her relationships were with women whom she described as "extremely feminine and heterosexual". In her younger years, Murray often was devastated by the end of these relationships, to the extent that she was hospitalized for psychiatric treatment twice, in 1937 and in 1940.[9]

Murray wore her hair short and preferred pants to skirts; due to her slight build, there was a time in her life when she was often able to pass as a teenage boy.[82] In her twenties, she shortened her name from Pauline to the more androgynous Pauli.[84] At the time of her arrest for the bus segregation protest in 1940, she gave her name as "Oliver" to the arresting officers.[85] Murray pursued hormone treatments in the 1940s to correct what she saw as a personal imbalance[37] and even requested abdominal surgery to test if she had "submerged" male sex organs.[86]

Writing about Murray's understanding of her sex, Rosalind Rosenberg, author of Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray, categorized Murray as a transgender man. When asked about her understanding of Murray's gender in a 2017 interview with the African American Intellectual History Society, Rosenberg states: "[During Pauli's life,] the term transgender did not exist and there was no social movement to support or help make sense of the trans experience. Murray's papers helped me to understand how her struggle with gender identity shaped her life as a civil rights pioneer, legal scholar, and feminist."[87] In an interview with HuffPost Queer Voices, Brittney Cooper agreed on the matter: "Murray preferred androgynous dress, had a short hairstyle and may have identified as a transgender male today, but she lacked the language to do so at the time."[85] While she lived openly in lesbian relationships for a time, her career, her Communist politics, and respectability politics shut down her options.[88][89]

Relationships

It has been said that Murray had just two significant romantic relationships in her life, both with white women. The first, in 1934, was brief. The second was with Irene "Renee" Barlow, an office manager at Paul, Weiss, where Murray worked as an associate attorney from 1956 to 1960. Murray's relationship with Barlow lasted nearly two decades. Barlow has been described by Murray's biographer as Pauli's "life partner", although the pair never lived in the same house and only occasionally lived in the same city. Due to Murray destroying Barlow's letters, a lot of the story is unknowable. However, while Barlow does not make an appearance in Murray's memoir, when Barlow was dying of a brain tumor, in 1973, she describes Pauli as "my closest friend".[90]

Pronouns

In an essay titled "Pauli Murray and the Pronominal Problem", transgender scholar-activist Naomi Simmons-Thorne lends support behind the emerging view of Murray as an early transgender figure in U.S. history.[91] In her essay, she calls upon historians and scholars to complement this growing interpretation through the use of masculine pronouns to reflect Murray's masculine perception of self. Simmons-Thorne is not the first academic to draw attention to the issue of Murray's pronouns, however. Historian Simon D. Elin Fisher has also challenged the historical and textual practices of assigning Murray female pronouns through their pronominal use of "s/he" in some of their writings.[92] Simmons-Thorne, however, makes exclusive use of "he-him-his" pronouns in reference to Murray. She conceives of the practice as one of many "de-essentialist" trans historiographical methods capable of "interrupt[ing] the logic of biological determinism" and "the constraints of cissexism operating historically."[91] Her view is a radical departure from biographers and scholars like Rosenberg, and conventional practices more broadly, which generally refer to Murray through the use of "she-her-hers" pronouns.[87]

Memoirs and poetry

In addition to her legal work, Murray wrote two volumes of autobiography and a collection of poetry. Her first autobiographical book, Proud Shoes (1956), traces her family's complicated racial origins, particularly focusing on her maternal grandparents, Robert and Cornelia Fitzgerald. Cornelia was the daughter of a slave who had been raped by her white owner and his brother. Born into slavery, the mixed-race girl was raised by her owner's sister and educated. Robert was a free black man from Pennsylvania, also of mixed racial ancestry; he moved to the South to teach during the Reconstruction Era. Newspapers, including The New York Times, gave the book very positive reviews. The New York Herald Tribune stated that Proud Shoes is "a personal memoir, it is history, it is biography, and it is also a story that, at its best, is dramatic enough to satisfy the demands of fiction. It is written in anger, but without hatred; in affection, but without pathos and tears; and in humor that never becomes extravagant."[93]

Murray published a collection of her poetry, Dark Testament and Other Poems, in 1970. The title poem, "Dark Testament", originally appeared in the winter 1944–45 issue of Lillian Smith and Paula Snelling's South Today. The volume contains what critic Christina G. Bucher calls a number of "conflicted love poems", as well as those exploring economic and racial injustice. The poem "Ruth" is included in the 1992 anthology Daughters of Africa.[94] Dark Testament has received little critical attention, and as of 2007, was out of print.[86] It was republished in 2018, following publication of a new biography about Murray in 2017.[4]

A follow-up volume to Proud Shoes, her memoir Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage, was published posthumously in 1987. Song focused on Murray's own life, particularly her struggles with both gender and racial discrimination. It received the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, the Christopher Award, and the Lillian Smith Book Award.[95]

Works by Murray

Law

- Murray, Pauli (Editor) (1952) States' Laws on Race and Color (Studies in the Legal History of the South), Athens: University of Georgia Press, Reprint edition, 2016. ISBN 9-780-8203-5063-9

- Murray, Pauli and Rubin, Leslie. The Constitution and Government of Ghana, London: Sweet & Maxwell, 1964. ISBN 978-0421041806, OCLC 491764185

Poetry

- Dark Testament and Other Poems, Connecticut: Silvermine Publishers, 1970. ISBN 978-0-87321-016-4

Autobiographies

- Proud Shoes: The Story Of An American Family, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956. ISBN 0-8070-7209-5.

- Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage, New York: Harper & Row, 1987. ISBN 0-06-015704-6. Reissued as Pauli Murray: The Autobiography of a Black Activist, Feminist, Lawyer, Priest and Poet, University of Tennessee Press, 1989. ISBN 0-87049-596-8

Notes

- Kenneth W. Mack states that the woman friend in question was likely Peg Holmes.[37]

References

- Pinn 1999, p. 29.

- Mack, Kenneth W. (February 29, 2016). "Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt's Beloved Radical". Boston Review. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- "Dr. Pauli Murray, Episcopalian Priest". The New York Times. July 4, 1985. p. 12. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Schulz, Kathryn (April 17, 2017). "The Many Lives of Pauli Murray". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- Cain, Brooke; Quillin, Martha (February 19, 2021). "10 NC Black History Lessons You Likely Weren't Taught in School (but Should Have Been)". Raleigh News & Observer. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- "Jane Crow & the Story of Pauli Murray". National Museum of African American History and Culture. March 24, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- Ahmed 2006.

- Kerber, Linda K. (August 1, 1993). "Judge Ginsburg's Gift". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- Mack 2012, p. 214.

- Sanchez 2003, p. 134.

- Hightower-Langston 2002, p. 160; Mack 2012, pp. 208–209.

- Bell-Scott 2016, p. 8; Mack 2012, p. 208; Sanchez 2003, p. 134.

- Rosenberg 2017, p. 15.

- Bell-Scott 2016, p. 8.

- Bell-Scott 2016, pp. 8–9; Mack 2012, p. 209; Murray 1999, p. xv.

- "The Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray and the Episcopal Church". Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- Bucher 2007, p. 441.

- Mack 2012, p. 209.

- Bell-Scott 2016, p. 10.

- Rosenberg 2017, pp. 37–38.

- Rosenberg 2017, p. 38.

- Bell-Scott 2016, p. 192; Rosenberg 2017, p. 38.

- McNeil, Genna Rae. "Interview with Pauli Murray, February 13, 1976. Interview G-0044. Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007)". Documenting the American South. Archived from the original on January 10, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- Hightower-Langston 2002, p. 160.

- Rosenberg 2017, pp. 54–55.

- Murray, Pauli; Bell-Scott, Patricia (May 8, 2018). "9". Song in a Weary Throat: Memoir of an American Pilgrimage. Boni & Liveright. ISBN 9781631494598.

- "She-She-She Camps". Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- Mack 2012, p. 213.

- Bell-Scott 2016, p. 18.

- Mack 2012, pp. 213–214.

- Atwell 2002.

- "Pauli Murray Hall: UNC's Departments of History, Political Science, and Sociology and the Curriculum on Peace, War, and Defense Begin the Renaming of Hamilton Hall". University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. July 28, 2020. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- Mack 2012, pp. 217–219.

- Mack 2012, p. 218.

- Mack 2012, pp. 218–219.

- Mack 2012, pp. 214–216.

- Mack 2012, p. 216.

- Mack 2012, p. 217.

- Mack 2012, pp. 221–222.

- Mack 2012, p. 225.

- Sherman 1992, p. 38.

- Sherman 1992, p. 39.

- Atwell 2002; Sherman 1992, p. 40.

- Sherman 1992, p. 42.

- Goodwin 1994, p. 352.

- Goodwin 1994, p. 354; Sherman 1992, p. 42.

- Sherman 1992, p. 164.

- Mack 2012, p. 226.

- Guy-Sheftall 1995, p. 185.

- Hightower-Langston 2002, p. 160; Mack 2012, p. 229.

- Rosenberg 2017, pp. 4, 118.

- Keller & Keller 2001, p. 58.

- Azaransky 2011, p. 36.

- Ahmed 2006; Atwell 2002.

- Rosenbaum, Leah. "Meet the Forgotten Woman Who Forever Changed the Lives of LGBTQ+ Workers". Forbes. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- Lerner 1973, pp. 592–599.

- Collier-Thomas 2010, p. 493.

- Cole & Guy-Sheftall 2009, p. 89.

- Freeman, Jo (March 1991). "How 'Sex' Got into Title VII: Persistent Opportunism as a Maker of Public Policy". Law and Inequality. 9 (2): 163–184.

- Anderson 2004, pp. 101–102.

- Hartmann 2002.

- "White v. Crook". Justia. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- Ahmed 2006; Azaransky 2011, p. 59.

- Simon, Amanda (April 28, 2016). "New Residential College at Yale to Be Named after Former Ford Fellow". Ford Foundation. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- Antler 2002, pp. 78, 80.

- Antler 2002.

- Armentrout, Don S.; Slocum, Robert Boak (January 2000). "An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church – Murray, Pauli". Episcopal Church. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- "Pauli Murray's Spiritual Journey". Emmanuel Episcopal Church. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- Boodman, Sandra G. (February 14, 1977). "The Poet as Lawyer and Priest". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- Rosenberg 2017, p. 371.

- "Papers of Pauli Murray, 1827–1985: A Finding Aid". Harvard Library. Archived from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Holy Women, Holy Men: Celebrating the Saints – Additional Commemorations (PDF). New York: Church Publishing. September 2013. p. 5.

- "News Coverage – Read about the July Celebration of Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray at St. Titus' Episcopal Church". Pauli Murray Project. July 1, 2013. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- Johnston, Flo (July 13, 2012). "Durham's Pauli Murray to Be Named Episcopal Saint". The News & Observer. Raleigh, North Carolina. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- Wise, Jim (March 26, 2015). "Durham's Pauli Murray Home Named 'National Treasure'". The News & Observer. Raleigh, North Carolina. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- Remnick, Noah (April 27, 2016). "Defying Protests, Yale Will Keep Name of a White Supremacist on a College". The New York Times. p. A19. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Vaughan, Dawn Baumgartner (June 13, 2017). "Pauli Murray's Landmark House to Become More Accessible". The Harold-Sun. Durham, North Carolina: The McClatchy Company. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Lord, Debbie (February 24, 2018). "National Women's History Month: What Is It, When Did It Begin, Who Is Being Honored This Year?". KIRO 7. Seattle, Washington: Cox Media Group. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Frances, Mary (July 13, 2018). "Convention makes Thurgood Marshall, Pauli Murray, Florence Li Tim-Oi Permanent Saints of the Church". Episcopal News Service. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- Dry, Jude (February 2, 2021). "'My Name Is Pauli Murray' Review: Trailblazing Civil Rights Disruptor Gets Overdue Tribute". IndieWire. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- Kennedy, Lisa (February 2, 2021). "'My Name Is Pauli Murray' Review: 'RBG' Directors Honor Another Civil Rights Leader". Variety. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- Mack 2012, p. 211.

- Mack 2012, pp. 214–215.

- Mack 2012, p. 212.

- Gebreyes, Rahel (February 10, 2015). "How 'Respectablity Politics' Muted the Legacy of Black LGBT Activist Pauli Murray". The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Bucher 2007, p. 442.

- Collins, Alyssa (October 16, 2017). "The Life of Pauli Murray: An Interview with Rosalind Rosenberg". Black Perspectives. African American Intellectual History Society.

- Cooper, Brittney (February 18, 2015). "Black, Queer, Feminist, Erased from History: Meet the Most Important Legal Scholar You've Likely Never Heard Of". Salon. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- Gebreyes, Rahel (February 10, 2015). "The Ahead-of-Her-Time Black LGBT Activist You Need to Know About". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- Schulz, Kathryn (April 10, 2017). "The Civil-Rights Luminary You've Never Heard Of". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- Simmons-Thorne, Naomi (May 30, 2019). "Pauli Murray and the Pronominal Problem: A De-Essentialist Trans Historiography". The Activist History Review.

- Fisher 2016.

- Bucher 2007, pp. 441–442.

- Busby, Margaret, ed. (1992). Daughters of Africa. p. 227.

- Ahmed 2006; Bucher 2007, p. 442.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, Siraj (2006). "Murray, Pauli". Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2013 – via HighBeam Research.

- Anderson, Terry H. (2004). The Pursuit of Fairness: A History of Affirmative Action. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518245-3.

- Antler, Joyce (2002). "Pauli Murray: The Brandeis Years". Journal of Women's History. 14 (2): 78–82. doi:10.1353/jowh.2002.0034. ISSN 1527-2036. S2CID 144692960.

- Atwell, Mary Welek (2002). "Murray, Pauli (1910–1985)". Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Gale Research. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2013 – via HighBeam Research.

- Azaransky, Sarah (2011). The Dream Is Freedom: Pauli Murray and American Democratic Faith. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199744817.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-974481-7.

- Bell-Scott, Patricia (2016). The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-44652-1.

- Bucher, Christina G. (2007). "Pauli Murray (1910–1985)". In Williams Page, Yolanda (ed.). Encyclopedia of African American Women Writers. Vol. 2. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 441–443. ISBN 978-0-313-34124-3.

- Cole, Johnnetta Betsch; Guy-Sheftall, Beverly (2009). Gender Talk: The Struggle For Women's Equality in African American Communities. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-307-52768-4.

- Collier-Thomas, Bettye (2010). Jesus, Jobs, and Justice: African American Women and Religion. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-1-4000-4420-7. OL 24547298M.

- Fisher, Simon D. Elin (2016). "Pauli Murray's Peter Panic: Perspectives from the Margins of Gender and Race in Jim Crow America". Transgender Studies Quarterly. 3 (1–2): 95–103. doi:10.1215/23289252-3334259. ISSN 2328-9260. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns (1994). No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-80448-4.

- Guy-Sheftall, Beverly (1995). Words of Fire: An Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought. New York: The New Press. ISBN 978-1-56584-256-4.

- Hartmann, Susan (2002). "Pauli Murray and the Juncture of Women's Liberation and Black Liberation". Journal of Women's History. 14 (2): 74–77. doi:10.1353/jowh.2002.0044. ISSN 1527-2036. S2CID 144549099.

- Hightower-Langston, Donna (2002). A to Z of American Women Leaders and Activists. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-1-4381-0792-9.

- Keller, Morton; Keller, Phyllis (2001). Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America's University. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514457-4.

- Lerner, Gerda (1973). Black Women in White America (2nd ed.). New York: Random House.

- Mack, Kenneth W. (2012). Representing the Race: The Creation of the Civil Rights Lawyer. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04687-0.

- Murray, Pauli (1999) [1956]. Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-7209-7.

- Pinn, Anthony B. (1999). "Religion and 'America's Problem Child': Notes on Pauli Murray's Theological Development". Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. 15 (1): 21–39. ISSN 1553-3913. JSTOR 25002350.

- Rosenberg, Rosalind (2017). Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-065645-4.

- Sanchez, Brenna (2003). "Murray, Pauli 1910–1985". In Henderson, Ashyia N. (ed.). Contemporary Black Biography. Vol. 38. Detroit, Michigan: Gale (published 2007). pp. 134–137. ISBN 978-1-4144-3566-4. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2013 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- Sherman, Richard B. (1992). The Case of Odell Waller and Virginia Justice, 1940–1942. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-733-9.

Further reading

Books

- Cooper, Brittney C. (2017). Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09954-0.

- Drury, Maureen M. (2012). "Love, Ambition, and 'Invisible Footnotes' in the Life and Writings of Pauli Murray". In McGlotten, Shaka; Davis, Dána-Ain (eds.). Black Genders and Sexualities. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 69–84. doi:10.1057/9781137077950_5. ISBN 978-1-137-07795-0. S2CID 143453655.

- Hardison, Ayesha K. (2014). Writing through Jane Crow: Race and Gender Politics in African American Literature. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press. pp. i–vi. ISBN 978-0-8139-3592-8. JSTOR j.ctt6wrn9t.1.

- Kujawa-Holbrook, Sheryl A., ed. (2002). "Anna Pauline 'Pauli' Murray (1911–1985)". Freedom Is a Dream: A Documentary History of Women in The Episcopal Church. New York: Church Publishing. pp. 272–279.

- Pinn, Anthony B., ed. (2006). Pauli Murray: Selected Sermons and Writings. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books. ISBN 978-0-87049-596-0.

- Scott, Anne Firor, ed. (2006). Pauli Murray and Caroline Ware: Forty Years of Letters in Black and White. University of North Carolina Press. doi:10.5149/9780807876732_scott. ISBN 978-0-8078-3055-0. JSTOR 10.5149/9780807876732_scott.

Articles

- Crosby, Emilye (May 12, 2021). "Pauli Murray: A Personal and Political Life". The Sixties. 14: 104–106. doi:10.1080/17541328.2021.1923160. S2CID 235812349.

- Garrett, Brianne; Rosenbaum, Leah (June 26, 2020). "Meet the Forgotten Woman Who Forever Changed the Lives of LGBTQ+ Workers". Forbes. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Lau, Barbara (April 17, 2017). "Defying Convention: The Life and Legacy of Pauli Murray" (PDF). The LGBT Bar. Retrieved February 20, 2021. (Five-page PDF with bibliography of books and articles by and about Murray)

- Shulz, Kathryn (April 17, 2017). "The Many Lives of Pauli Murray". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

External links

- National Organization for Women: Finding Pauli Murray, Excellent links to Murray resources. Printable PDF.

- Oral History Interview with Pauli Murray from Oral Histories of the American South at UNC-Chapel Hill, NC

- Pauli Murray Award by Orange County, NC

- Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice in Durham, NC

- Pauli Murray College at Yale University, New Haven, CT

- Pauli Murray Papers at Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

- Pauli Murray poetry (after bio) at the Poetry Foundation, Chicago, IL

- The Pioneering Pauli Murray: Lawyer, Activist, Scholar and Priest, National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, DC

- The Reverend Pauli Murray, 1910–1985, Archives of the Episcopal Church