Pied-Noir

The Pieds-Noirs (French: [pje nwaʁ]; French for 'Black Feet'; sg. Pied-Noir), are the people of French and other European descent who were born in Algeria during the period of French rule from 1830 to 1962, the vast majority of whom departed for mainland France as soon as Algeria gained independence or in the months following.[3][4]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1959: 1.4 million[1] (13% of the population of Algeria) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Algiers, Oran, Constantine | |

| Languages | |

| French, Spanish, Catalan, Occitan, Maghrebi Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Christianity (Roman Catholicism, Protestantism) Minority: Judaism |

From the French invasion on 18 June 1830 until its independence, Algeria was administratively part of France; its European population were simply called Algerians or colons (colonists), whereas the Muslim people of Algeria were called Arabs, Muslims or Indigenous. The term "pied-noir" began to be commonly used shortly before the end of the Algerian War in 1962. As of the last census in French-ruled Algeria, taken on 1 June 1960, there were 1,050,000 non-Muslim civilians (mostly Catholic, but including 130,000 Algerian Jews) in Algeria, 10 per cent of the population.[5]

During the Algerian War the Pieds-Noirs overwhelmingly supported colonial French rule in Algeria and were opposed to Algerian nationalist groups such as the Front de libération nationale (English: National Liberation Front) (FLN) and Mouvement national algérien (English: Algerian National Movement) (MNA). The roots of the conflict lay in political and economic inequalities perceived as an "alienation" from the French rule as well as a demand for a leading position for the Berber, Arab and Islamic cultures and rules existing before the French conquest. The conflict contributed to the fall of the French Fourth Republic and the exodus of European and Jewish Algerians to France.[4][6]

After Algeria became independent in 1962, about 800,000 Pieds-Noirs of French nationality were evacuated to mainland France, while about 200,000 remained in Algeria. Of the latter, there were still about 100,000 in 1965 and about 50,000 by the end of the 1960s.[7]

Those who moved to France suffered ostracism from the left for their perceived exploitation of native Muslims, while others blamed them for the war and thus for the political turmoil surrounding the collapse of the Fourth Republic.[4] In popular culture, the community is often represented as feeling removed from French culture while longing for Algeria.[4][6] Thus, the recent history of the Pieds-Noirs has been characterized by a sense of twofold alienation, on the one hand from the land of their birth and on the other from their adopted homeland. Though the term rapatriés d'Algérie implies that prior to Algeria they once lived in France, most Pieds-Noirs were born in Algeria.

Etymology

There are competing theories about the origin of the term "pied-noir". According to the Oxford English Dictionary, it refers to "a person of European origin living in Algeria during the period of French rule, especially a French person expatriated after Algeria was granted independence in 1962."[3] The Le Robert dictionary states that in 1901 the word indicated a sailor working barefoot in the coal room of a ship, who would find his feet blackened by the soot and dust. Since, in the Mediterranean, this was often an Algerian native, the term was used pejoratively for Algerians until 1955 when it first began referring to "French born in Algeria" according to some sources.[8][9] The Oxford English Dictionary claims this usage originated from mainland French as a negative nickname.[3]

There is also a theory that the term comes from the black boots of French soldiers compared to the barefoot Algerians.[10] Other theories focus on new settlers dirtying their clothing by working in swampy areas, wearing black boots when on horseback, or trampling grapes to make wine.[11]

History

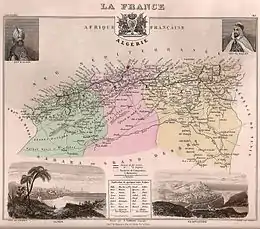

French conquest and settlement

European settlement of Algeria began during the 1830s, after France had commenced the process of conquest with the military seizure of the city of Algiers in 1830. The invasion was instigated when the Dey of Algiers struck the French consul with a fly-swatter in 1827, although economic reasons are also cited. In 1830 the government of King Charles X blockaded Algeria and an armada sailed to Algiers, followed by a land expedition. A troop of 34,000 soldiers landed on 18 June 1830, at Sidi Ferruch, 27 kilometres (17 mi) west of Algiers. Following a three-week campaign, the Hussein Dey capitulated on 5 July 1830 and was exiled.[12][13][14]

In the 1830s the French controlled only the northern part of the country.[13] Entering the Oran region, they faced resistance from Emir Abd al-Kader, a leader of a Sufi Brotherhood.[15][16] In 1839 Abd al-Kader began a seven-year war by declaring jihad against the French. The French signed two peace treaties with Al-Kader, but they were broken because of a miscommunication between the military and the government in Paris. In response to the breaking of the second treaty, Abd al-Kader drove the French to the coast. In reply, a force of nearly 100,000 troops marched to the Algerian countryside and forced Abd al-Kader's surrender in 1847.[15]

In 1848 Algeria was divided into three departments (Alger, Oran and Constantine), thus becoming part of France.[14][15]

The French modeled their colonial system on their predecessors, the Ottomans, by co-opting local tribes. In 1843 the colonists began supervising through bureaux arabes[12][17] operated by military officials with authority over particular domains.[17] This system lasted until the 1880s and the rise of the French Third Republic, when colonisation intensified.[5] Large-scale regrouping of lands began when land-speculation companies took advantage of government policy that allowed massive sale of native property. By the 20th century Europeans held 1,700,000 hectares; by 1940, 2,700,000 hectares, about 35 to 40 percent;[12] and by 1962 it was 2,726,700 hectares representing 27 percent of the arable land of Algeria.[18] Settlers came from all over the western Mediterranean region, particularly Italy, France, Spain and Malta.[4]

Relationship to mainland France and Muslim Algeria

The Pied-Noir relationship with France and Algeria was marked by alienation. The settlers considered themselves French,[19] but many of the Pieds-Noirs had a tenuous connection to mainland France, which 28 percent of them had never visited. The settlers encompassed a range of socioeconomic strata, ranging from peasants to large landowners, the latter of whom were referred to as grands colons.[19][20]

In Algeria, the Muslims were not considered French and did not share the same political or economic benefits.[19] For example, the indigenous population did not own most of the settlements, farms, or businesses, although they numbered nearly nine million (versus roughly one million Pieds-Noirs) at independence. Politically, the Muslim Algerians had no representation in the French National Assembly until 1945 and wielded limited influence in local governance.[21] To obtain citizenship, they were required to renounce their Muslim identity. Since this would constitute apostasy, only about 2,500 Muslims acquired citizenship before 1930.[20][21] The settlers' politically and economically dominant position worsened relations between the two groups.

The Pied-Noir population as part of the total Algerian population

From roughly the last half of the 19th century until independence, the Pieds-Noirs accounted for approximately 10% of the total Algerian population. Although they constituted a numerical minority, they were undoubtedly the prime political and economic force of the region.

In 1959, the Pieds-Noirs numbered 1,025,000, and accounted for 10.4% of the total population of Algeria, a percentage gradually diminishing since the peak of 15.2% in 1926. However, some areas of Algeria had high concentrations of Pieds-Noirs, such as the regions of Bône (now Annaba), Algiers, and above all the area from Oran to Sidi-Bel-Abbès.[22] Oran had been under European rule since the 16th century (1509); the population in the Oran metropolitan area was 49.3% European and Jewish in 1959.

In the Algiers metropolitan area, Europeans and Jewish people accounted for 35.7% of the population. In the metropolitan area of Bône they accounted for 40.5% of the population. The département of Oran, a rich European-developed agricultural land of 16,520 km2 (6,378 sq. miles) stretching between the cities of Oran and Sidi-Bel-Abbès, and including them, was the area of highest Pied-Noir density outside of the cities, with the Pieds-Noirs accounting for 33.6% of the population of the département in 1959.

| Year | Algerian Population | Pied Noir population |

|---|---|---|

| 1830 | 1,500,000 | 14,000 (in 1836) |

| 1851 | 2,554,100 | 100,000 (in 1847) |

| 1960 | 10,853,000 | 1,111,000 (in 1959) |

| 1965 | 11,923,000 | 100,000 (in 1965) |

Sephardic Jewish community

Jews were present in North Africa and Iberia for centuries, some since the time when "Phoenicians and Hebrews, engaged in maritime commerce, founded Hippo Regius (current Annaba), Tipasa, Caesarea (current Cherchel), and Icosium (current Algiers)".[27] According to oral tradition they arrived from Judea after the First Jewish-Roman War (66–73 AD), while it is known historically that many Sephardi Jews came following the Spanish Reconquista.[28] In 1870, Justice Minister Adolphe Crémieux wrote a proposal, décret Crémieux, giving French citizenship to Algerian Jews. This advancement was resisted by part of the larger Pied-Noir community and in 1897 a wave of anti-Semitic riots occurred in Algeria. During World War II the décret Crémieux was abolished under the Vichy regime, and Jews were barred from professional jobs between 1940 and 1943.[27] Citizenship was restored in 1943, after the Free French took control over Algeria in the wake of Operation Torch. Thus, the Jews of Algeria eventually came to be considered part of the Pied-Noir community,[28] and many fled the country to France in 1962, alongside most other Pieds-Noirs, after the Algerian War.[29]

Algerian War

For more than a century France maintained colonial rule in Algerian territory. This allowed exceptions to republican law, including Sharia laws applied by Islamic customary courts to Muslim women which gave women certain rights to property and inheritance that they did not have under French law.[27] Discontent among the Muslim Algerians grew after the World Wars, in which the Algerians sustained many casualties.[27] Algerian nationalists began efforts aimed at furthering equality by listing complaints in the Manifesto of the Algerian People, which requested equal representation under the state and access to citizenship, but no equality for all citizens to preserve Islamic precepts. The French response was to grant citizenship to 60,000 "meritorious" Muslims.[13] During a reform effort in 1947, the French laws were changed to give the former French subjects with the legal status of "indigenes" full French legal citizenship. The French created an Algerian Assembly, a form of bicameral legislature, with limited powers, and two chambers, one for those who were French citizens before 1947, and another for all the others who had only just become French citizens; but gave the equal numbers of members in each chamber meant that one group's votes had seven times more weight than the other group's.[20] Paramilitary groups such as the National Liberation Front (Front de Libération nationale, FLN) appeared, claiming an Arab-Islamic brotherhood and state.[27] This led to the outbreak of a war for independence, the Algerian War, in 1954.

From the first armed operations of November 1954, Pied-Noir civilians had always been targets for the FLN, either by assassination; bombing bars and cinemas; mass massacres; torture; and rapes in farms.[30] At the onset of the war, the Pieds-Noirs believed the French military would be able to overcome opposition. In May 1958 a demonstration for French Algeria, led by Pieds-Noirs but including many Muslims, occupied an Algerian government building. Plots to overthrow the Fourth Republic, some including metropolitan French politicians and generals, had been swirling in Algeria for some time.[31] General Jacques Massu controlled the riot by forming a 'Committee of Public Safety' demanding that his acquaintance Charles de Gaulle be named president of the French Fourth Republic, to prevent the "abandonment of Algeria". This eventually led to the fall of the Republic.[19] In response, the French Parliament voted 329 to 224 to place de Gaulle in power.[19] Once de Gaulle assumed leadership, he attempted peace by visiting Algeria within three days of his appointment, proclaiming "French Algeria!"; but in September 1959 he planned a referendum for Algerian self-determination that passed overwhelmingly.[19] Many French political and military leaders in Algeria viewed this as a betrayal and formed the Organisation armée secrète (OAS) that had much support among Pieds-Noirs. This paramilitary group began attacking officials representing de Gaulle's authority, Muslims, and de Gaulle himself.[19] The OAS was also accused of murders and bombings which nullified any remaining reconciliation opportunities between the communities,[32] while Pieds-Noirs themselves never believed such reconciliation possible as their community was targeted from the start.[30]

The opposition culminated in the Algiers putsch of 1961, led by retired generals. After its failure, on 18 March 1962, de Gaulle and the FLN signed a cease-fire agreement, the Évian Accords, and held a referendum. In July, Algerians voted 5,975,581 to 16,534 to become independent from France.[20] This triggered a massacre of Pieds-Noirs in Oran by a suburban Muslim population. European people were shot, raped, lynched and brought to Petit-Lac slaughterhouse where they were tortured and executed.[33]

Exodus

The exodus began once it became clear that Algeria would become independent.[8] In Algiers, it was reported that by May 1961 the Pieds-Noirs' morale had sunk because of violence and allegations that the entire community of French nationals had been responsible for "terrorism, torture, colonial racism, and ongoing violence in general" and because the group felt "rejected by the nation as Pieds-Noirs ".[8] These factors, the Oran Massacre, and the referendum for independence caused the Pied-Noir exodus to begin in earnest.[4][6][8]

The number of Pieds-Noirs who fled Algeria totalled more than 800,000 between 1962 and 1964.[32] Many Pieds-Noirs left only with what they could carry in a suitcase.[6][32] Adding to the confusion, the de Gaulle government ordered the French Navy not to help with transportation of French citizens.[20] By September 1962, cities such as Oran, Bône, and Sidi Bel Abbès were half-empty. All administration-, police-, school-, justice-, and commercial activities stopped within three months after many Pieds-Noirs were told to choose either "la valise ou le cercueil" (the suitcase or the coffin).[27] 200,000 Pieds-Noirs chose to remain, but they gradually left through the following decades; by the 1980s only a few thousand Pieds-Noirs remained in Algeria.[7][19]

Along with the exodus of the Pieds-Noirs, occurred the flight of the Muslim harki auxiliaries who had fought on the French side during the Algerian War. Of approximately 250,000 Muslim loyalists only about 90,000, including dependents, were able to escape to France; and of those who remained many thousands were killed by lynch mobs or executed as traitors by the FLN. In contrast to the treatment of the European Pieds-Noirs, little effort was made by the French government to extend protection to the harkis or to arrange their organised evacuation.[34]

Flight to mainland France

The Government of France claimed that it had not anticipated that such a massive number would leave; it believed that perhaps 300,000 might choose to depart temporarily and that a large portion would return to Algeria.[8] The administration had set aside funds for absorption of those it called repatriates to partly reimburse them for property losses.[20] The administration avoided acknowledging the true numbers of refugees to avoid upsetting its Algeria policies.[20] Consequently, few plans were made for their return, and, psychologically at least, many of the Pieds-Noirs were alienated from both Algeria and France.[4]

Many Pieds-Noirs settled in continental France, while others migrated to New Caledonia,[35] Australia,[35] Spain,[36] Israel,[37] Argentina,[38][39] Italy, the United States and Canada. In France, many relocated to the south, which offered a climate similar to North Africa. The influx of new citizens bolstered the local economies; however, the newcomers also competed for jobs, which caused resentment.[6][20] One unintended consequence with significant and ongoing political effects was the resentment caused by the state resettlement programme for Pieds-Noirs in rural Corsica, which triggered a cultural and political nationalist movement.[40] In some ways, the Pieds-Noirs were able to integrate well into the French community, in particular relative to their harki Muslim counterparts.[41] Their resettlement was made easier by the economic boom of the 1960s. However, the ease of assimilation depended on socioeconomic class. Integration was easier for the upper classes, many of whom found the transformation less stressful than the lower classes, whose only capital had been left in Algeria when they fled. Many were surprised at often being treated as an "underclass or outsider-group" with difficulties in gaining advancement in their careers. Also, many Pieds-Noirs contended that the money allocated by the government to assist in relocation and reimbursement was insufficient regarding their loss.[6][20]

Thus, the repatriated Pieds-Noirs frequently felt "disaffected" from French society. They also suffered from a sense of alienation stemming from the French government's changed position towards Algeria. Until independence, Algeria was legally a part of France; after independence many felt that they had been betrayed and were now portrayed as an "embarrassment" to their country or to blame for the war.[6][42] Most Pied-Noirs felt a powerful sense of loss and a longing for their lost homeland in Algeria.[43] The American author Claire Messud remembered seeing her pied-noir father, a lapsed Catholic crying while watching Pope John Paul II deliver a Mass on his TV. When asked why, Messud père replied: "Because when I last heard the mass in Latin, I thought I had a religion, and I thought I had a country."[43] Messud noted that the novelist Albert Camus, himself a pied-noir, had often written of his love for the sea-shores and mountains of Algeria, declaring Algeria was a place that was a part of his soul, feelings she noted mirrored those of other pied-noirs for whom Algeria was the only home they had ever known.[43]

Flags

Flag proposed by Jean-Paul Gavino[44]

Flag proposed by Jean-Paul Gavino[44].svg.png.webp) Tricolore flag with two black feet[45]

Tricolore flag with two black feet[45] Flag of the USDIFRA using pied-noir symbolism

Flag of the USDIFRA using pied-noir symbolism État Pied-Noir flag to the claim sovereignty and nationhood.

État Pied-Noir flag to the claim sovereignty and nationhood.

The Song of the Africans

The Pied-Noir community has adopted, as both an unofficial anthem and as a symbol of its identity, Captain Félix Boyer's 1943 version of "Le Chant des Africains" (lit. "The Song of the Africans").[46] This was a 1915 Infanterie de Marine marching song, originally titled "C'est nous les Marocains" (lit. "We are the Moroccans") and dedicated to Colonel Van Hecke, commander of a World War I cavalry unit: the 7e régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique ("7th African Light Cavalry Regiment"). Boyer's song was adopted during World War II by the Free French First Army that was drawn from units of the Army of Africa and included many Pieds-Noirs. The music and words were later utilized by the Pieds-Noirs to proclaim their allegiance to France. (listen to the Chant des Africains)

The "Song of the Africans" was banned from use as official military music in 1962 at the end of the Algerian War until August 1969, when the French Minister of Veterans Affairs (Ministre des Anciens Combattants) at the time, Henri Duvillard, lifted the prohibition.[47]

Notable Pieds-Noirs

- Louis Althusser, philosopher

- Jacques Attali, economist, writer

- Paul Belmondo, sculptor, father of the actor Jean-Paul Belmondo

- Patrick Bokanowski, filmmaker

- Patrick Bruel, singer

- Albert Camus, Nobel Prize winning author and philosopher

- Claude Cohen-Tannoudji, Nobel laureate

- Étienne Daho, singer

- Jacques Derrida, philosopher

- Annie Fratellini, circus clown

- Tony Gatlif, filmmaker

- Marlène Jobert, actress and author

- Alphonse Juin, Marshal of France

- Marcel Cerdan, boxer

- Jean-François Larios, footballer

- Enrico Macias, singer

- Jean Pélégri, author

- Emmanuel Roblès, author

- Yves Saint Laurent, fashion designer

See also

- Arab-Berber

- Kouloughlis

- Turco-Tunisians

- European Tunisians

- Italian Tunisians

- Etat Pied-Noir

- French people

- White Africans of European ancestry

- Processo Revolucionário Em Curso

- List of French possessions and colonies

Further reading

- Eldridge, Claire; Kalter, Christoph; Taylor, Becky (2022). "Migrations of Decolonization, Welfare, and the Unevenness of Citizenship in the UK, France and Portugal". Past & Present.

References

- De Azevedo, Raimondo Cagiano (1994) Migration and development co-operation.. Council of Europe. p. 25. ISBN 92-871-2611-9.

- Le vote pied-noir 50 ans après les accords d'Evian Archived 2015-11-20 at the Wayback Machine, Sciences Po, January 2012

- "pied-noir". Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Edition. Vol. XI. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press. 1989. pp. 799. ISBN 978-0-19-861223-0.

- Naylor, Phillip Chiviges (2000). France and Algeria: A History of Decolonization and Transformation. University Press of Florida. pp. 9–23, 14. ISBN 978-0-8130-3096-8.

- Cook, Bernard A. (2001). Europe since 1945: an encyclopedia. New York: Garland. pp. 398. ISBN 978-0-8153-4057-7.

- Smith, Andrea L. (2006). Colonial Memory And Postcolonial Europe: Maltese Settlers in Algeria And France. Indiana University Press. pp. 4–37, 180. ISBN 978-0-253-21856-8.

- "Pieds-noirs": ceux qui ont choisi de rester, La Dépêche du Midi, March 2012

- Shepard, Todd (2006). The Invention of Decolonization: The Algerian War And the Remaking of France. Cornell University Press. pp. 213–240. ISBN 978-0-8014-4360-2.

- "pied-noir". Dictionnaire Historique de la langue française. Vol. 2. Paris, France: Dictionnaires le Robert. March 2000. pp. 2728–9. ISBN 978-2-85036-532-4.

- "Pieds-noirs (histoire)" [Black feet (history)]. Microsoft Encarta Online (in French). 2008. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009.

- "Francparler.com - Voyons en détails..." 12 October 2005. Archived from the original on 12 October 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Lapidus, Ira Marvin (2002). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 585–600. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

- Country Studies Program; formerly the Army Handbook (2006). "Country Profile: Algeria" (PDF). Library of Congress, Federal Research Division. The Library of Congress. p. 3. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- Milton-Edwards, Beverley (2006). Contemporary Politics in the Middle East. Polity. pp. 28. ISBN 978-0-7456-3593-4.

french colonization of algeria.

- Churchill, Charles Henry (1867). The Life of Abdel Kader, Ex-sultan of the Arabs of Algeria. Chapman and Hall. pp. 270.

surrender of abdel al kader.

- Stone, Martin (1997). The Agony of Algeria. Columbia University Press. pp. 31–37. ISBN 978-0-231-10911-6.

french invasion of algeria.

- Amselle, Jean-Loup (2003). Affirmative exclusion: cultural pluralism and the rule of custom in France. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. pp. 65–100. ISBN 978-0-8014-8747-7.

- Les réformes agraires en Algérie - Lazhar Baci - Institut National Agronomique, Département d'Economie Rurale, Alger (Algérie)

- Grenville, J. A. S. (2005). A History of the World from the 20th to the 21st Century. Routledge. pp. 520–30. ISBN 978-0-415-28955-9.

- Kacowicz, Arie Marcelo; Pawel Lutomski (2007). Population Resettlement in International Conflicts: A Comparative Study. Lexington Books. pp. 30–70. ISBN 978-0-7391-1607-4.

- Kantowicz, Edward R. (2000). Coming apart, coming together. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans. pp. 207. ISBN 978-0-8028-4456-9.

- Albert Habib Hourani, Malise Ruthven (2002). "A history of the Arab peoples". Harvard University Press. p.323. ISBN 0-674-01017-5

- "ALGERIA: population growth of the whole country". Populstat.info. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Timelines : History of Algeria". Zum.de. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- The Agony of Algeria By Martin Stone published by Columbia University Press, 1997. ISBN 0231109113, page 32 (source for pieds-noir population in 1836 and 1847).

- "Pied-Noir". Encyclopedia of the Orient. Archived from the original on 2021-01-15. Retrieved 2015-07-18.

- Stora, Benjamin (2005). Algeria, 1830-2000: A Short History. Cornell University Press. pp. 12, 77. ISBN 978-0-8014-8916-7.

- Goodman, Martin; Cohen, Jeremy; Sorkin, David Jan (2005). The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 330–40. ISBN 978-0-19-928032-2.

- Grobman, Alex (1983). Genocide: Critical Issues of the Holocaust. Behrman House, Inc. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-940646-38-4.

- Courrières, Yves (1968). La Guerre d'Algerie. Fayard. p. 208. ISBN 978-2-213-61121-1.

- Bromberger, Merry and Serge (1959). Les 13 Complots du 13 Mai. Paris: Fayard.

- Meredith, Martin (27 June 2006). The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence. PublicAffairs. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-58648-398-2.

- Monneret, Jean (2006). Oran, 5 juillet 1962. Michalon. ISBN 978-2-84186-308-2.

- Horne, Alistair (1977). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962. The Viking Press. pp. 533 and 537. ISBN 978-0-670-61964-1.

- "French migration to South Australia (1955-1971): What Alien Registration documents can tell us". Vol. 2, Issue 2, August 2005. Flinders University Languages. Archived from the original on 2008-02-28. Retrieved 2007-12-25.

- Sempere Souvannavong, Juan David (11 January 2018). "Les pieds-noirs à Alicante". Revue Européenne de Migrations Internationales. 17 (3): 173–198. doi:10.3406/remi.2001.1800. hdl:10045/57388. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Vidéo: l'alyah des juifs d'Algérie - JSS News - Israël - Diplomatie - Géopolitique". 27 July 2010. Archived from the original on 27 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Verdo, Geneviève (2002). "L'exil, la mémoire et l'intégration culturelle : les Pieds-Noirs d'Argentine, des Argentins avant la lettre?". Matériaux Pour l'Histoire de Notre Temps. 67: 113–118. doi:10.3406/mat.2002.402404 – via Persée.

- "Les pieds noirs d'Argentine". Institut national de l'audiovisuel. 1964.

- Ramsay, pp. 39-40.

- Alba, Richard; Silberman, Roxane (December 2002). "Decolonization Immigrations and the Social Origins of the Second Generation: The Case of North Africans in France". International Migration Review. 36 (4): 1169–1193. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2002.tb00122.x. S2CID 145811837.

- Dine, Philip (1994). Images of the Algerian War: French Fiction and Film, 1954-1992. Oxford University Press. pp. 189–99. ISBN 978-0-19-815875-2.

- Messud, Claire (7 November 2013). "Camus & Algeria: The Moral Question". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- "fotw".

- "fotw".

- "Les Africains". nice.algerianiste.free.fr. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- John Franklin. "Mémoire Vive". Magazine du C.D.H.A. No. 32, 4th trimester 2005. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

Sources

- Ramsay, R. (1983) The Corsican Time-Bomb, Manchester University Press: Manchester. ISBN 0-7190-0893-X.