Peter Paul Rubens

Sir Peter Paul Rubens (/ˈruːbənz/;[1] Dutch: [ˈrybə(n)s]; 28 June 1577 – 30 May 1640) was a Flemish artist and diplomat from the Duchy of Brabant in the Southern Netherlands (modern-day Belgium).[2] He is considered the most influential artist of the Flemish Baroque tradition. Rubens's highly charged compositions reference erudite aspects of classical and Christian history. His unique and immensely popular Baroque style emphasized movement, colour, and sensuality, which followed the immediate, dramatic artistic style promoted in the Counter-Reformation. Rubens was a painter producing altarpieces, portraits, landscapes, and history paintings of mythological and allegorical subjects. He was also a prolific designer of cartoons for the Flemish tapestry workshops and of frontispieces for the publishers in Antwerp.

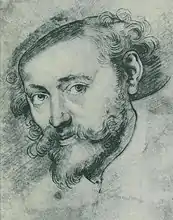

Sir Peter Paul Rubens | |

|---|---|

Self-Portrait, 1623, Royal Collection | |

| Born | 28 June 1577 Siegen, Nassau-Dillenburg, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 30 May 1640 (aged 62) Antwerp, Spanish Netherlands |

| Nationality | Flemish |

| Education | Tobias Verhaecht Adam van Noort Otto van Veen |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, tapestry design, print design |

| Movement | Flemish Baroque |

| Spouse(s) | Isabella Brant

(m. 1609; died 1626)Helena Fourment (m. 1630) |

| Signature | |

| |

In addition to running a large workshop in Antwerp that produced paintings popular with nobility and art collectors throughout Europe, Rubens was a classically educated humanist scholar and diplomat who was knighted by both Philip IV of Spain and Charles I of England. Rubens was a prolific artist. The catalogue of his works by Michael Jaffé lists 1,403 pieces, excluding numerous copies made in his workshop.[3]

His commissioned works were mostly history paintings, which included religious and mythological subjects, and hunt scenes. He painted portraits, especially of friends, and self-portraits, and in later life painted several landscapes. Rubens designed tapestries and prints, as well as his own house. He also oversaw the ephemeral decorations of the royal entry into Antwerp by the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Austria in 1635. He wrote a book with illustrations of the palaces in Genoa, which was published in 1622 as Palazzi di Genova. The book was influential in spreading the Genoese palace style in Northern Europe.[4] Rubens was an avid art collector and had one of the largest collections of art and books in Antwerp. He was also an art dealer and is known to have sold an important number of art objects to George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham.[5]

He was one of the last major artists to make consistent use of wooden panels as a support medium, even for very large works, but he used canvas as well, especially when the work needed to be sent a long distance. For altarpieces he sometimes painted on slate to reduce reflection problems.

Life

Early life

Rubens was born in Siegen to Jan Rubens and Maria Pypelincks. His father, a Calvinist, and mother fled Antwerp for Cologne in 1568, after increased religious turmoil and persecution of Protestants during the rule of the Habsburg Netherlands by the Duke of Alba. Rubens was baptised in Cologne at St Peter's Church.

Jan Rubens became the legal adviser (and lover) of Anna of Saxony, the second wife of William I of Orange, and settled at her court in Siegen in 1570, fathering her daughter Christine who was born in 1571.[6] Following Jan Rubens's imprisonment for the affair, Peter Paul Rubens was born in 1577. The family returned to Cologne the next year. In 1589, two years after his father's death, Rubens moved with his mother Maria Pypelincks to Antwerp, where he was raised as a Catholic.

Religion figured prominently in much of his work, and Rubens later became one of the leading voices of the Catholic Counter-Reformation style of painting[7] (he had said "My passion comes from the heavens, not from earthly musings").

Apprenticeship

In Antwerp, Rubens received a Renaissance humanist education, studying Latin and classical literature. By fourteen he began his artistic apprenticeship with Tobias Verhaeght. Subsequently, he studied under two of the city's leading painters of the time, the late Mannerist artists Adam van Noort and Otto van Veen.[8] Much of his earliest training involved copying earlier artists' works, such as woodcuts by Hans Holbein the Younger and Marcantonio Raimondi's engravings after Raphael. Rubens completed his education in 1598, at which time he entered the Guild of St. Luke as an independent master.[9]

Italy (1600–1608)

In 1600 Rubens traveled to Italy. He stopped first in Venice,[10] where he saw paintings by Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, before settling in Mantua at the court of Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga. The colouring and compositions of Veronese and Tintoretto had an immediate effect on Rubens's painting, and his later, mature style was profoundly influenced by Titian.[11] With financial support from the Duke, Rubens travelled to Rome by way of Florence in 1601. There, he studied classical Greek and Roman art and copied works of the Italian masters. The Hellenistic sculpture Laocoön and His Sons was especially influential on him, as was the art of Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci.[12] He was also influenced by the recent, highly naturalistic paintings by Caravaggio.

.jpg.webp)

Rubens later made a copy of Caravaggio's Entombment of Christ and recommended his patron, the Duke of Mantua, to purchase The Death of the Virgin (Louvre).[13] After his return to Antwerp he was instrumental in the acquisition of The Madonna of the Rosary (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) for the St. Paul's Church in Antwerp.[14] During this first stay in Rome, Rubens completed his first altarpiece commission, St. Helena with the True Cross for the Roman church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme.

Rubens travelled to Spain on a diplomatic mission in 1603, delivering gifts from the Gonzagas to the court of Philip III.[15] While there, he studied the extensive collections of Raphael and Titian that had been collected by Philip II.[16] He also painted an equestrian portrait of the Duke of Lerma during his stay (Prado, Madrid) that demonstrates the influence of works like Titian's Charles V at Mühlberg (1548; Prado, Madrid). This journey marked the first of many during his career that combined art and diplomacy.

He returned to Italy in 1604, where he remained for the next four years, first in Mantua and then in Genoa and Rome. In Genoa, Rubens painted numerous portraits, such as the Marchesa Brigida Spinola-Doria (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), and the portrait of Maria di Antonio Serra Pallavicini, in a style that influenced later paintings by Anthony van Dyck, Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough.[17]

He illustrated books, which was published in 1622 as Palazzi di Genova. From 1606 to 1608, he was mostly in Rome when he received, with the assistance of Cardinal Jacopo Serra (the brother of Maria Pallavicini), his most important commission to date for the High Altar of the city's most fashionable new church, Santa Maria in Vallicella also known as the Chiesa Nuova.

The subject was to be St. Gregory the Great and important local saints adoring an icon of the Virgin and Child. The first version, a single canvas (now at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Grenoble), was immediately replaced by a second version on three slate panels that permits the actual miraculous holy image of the "Santa Maria in Vallicella" to be revealed on important feast days by a removable copper cover, also painted by the artist.[18]

Rubens's experiences in Italy continued to influence his work. He continued to write many of his letters and correspondences in Italian, signed his name as "Pietro Paolo Rubens", and spoke longingly of returning to the peninsula—a hope that never materialized.[19]

Antwerp (1609–1621)

Upon hearing of his mother's illness in 1608, Rubens planned his departure from Italy for Antwerp. However, she died before he arrived home. His return coincided with a period of renewed prosperity in the city with the signing of the Treaty of Antwerp in April 1609, which initiated the Twelve Years' Truce. In September 1609 Rubens was appointed as court painter by Albert VII, Archduke of Austria, and Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain, sovereigns of the Low Countries.

He received special permission to base his studio in Antwerp instead of at their court in Brussels, and to also work for other clients. He remained close to the Archduchess Isabella until her death in 1633, and was called upon not only as a painter but also as an ambassador and diplomat. Rubens further cemented his ties to the city when, on 3 October 1609, he married Isabella Brant, the daughter of a leading Antwerp citizen and humanist, Jan Brant.

In 1610 Rubens moved into a new house and studio that he designed. Now the Rubenshuis Museum, the Italian-influenced villa in the centre of Antwerp accommodated his workshop, where he and his apprentices made most of the paintings, and his personal art collection and library, both among the most extensive in Antwerp. During this time he built up a studio with numerous students and assistants. His most famous pupil was the young Anthony van Dyck, who soon became the leading Flemish portraitist and collaborated frequently with Rubens. He also often collaborated with the many specialists active in the city, including the animal painter Frans Snyders, who contributed the eagle to Prometheus Bound (c. 1611–12, completed by 1618), and his good friend the flower-painter Jan Brueghel the Elder.

Another house was built by Rubens to the north of Antwerp in the polder village of Doel, "Hooghuis" (1613/1643), perhaps as an investment. The "High House" was built next to the village church.

Altarpieces such as The Raising of the Cross (1610) and The Descent from the Cross (1611–1614) for the Cathedral of Our Lady were particularly important in establishing Rubens as Flanders' leading painter shortly after his return. The Raising of the Cross, for example, demonstrates the artist's synthesis of Tintoretto's Crucifixion for the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice, Michelangelo's dynamic figures, and Rubens's own personal style. This painting has been held as a prime example of Baroque religious art.[20]

Rubens used the production of prints and book title-pages, especially for his friend Balthasar Moretus, the owner of the large Plantin-Moretus publishing house, to extend his fame throughout Europe during this part of his career. In 1618, Rubens embarked upon a printmaking enterprise by soliciting an unusual triple privilege (an early form of copyright) to protect his designs in France, the Southern Netherlands, and United Provinces.[21] He enlisted Lucas Vorsterman to engrave a number of his notable religious and mythological paintings, to which Rubens appended personal and professional dedications to noteworthy individuals in the Southern Netherlands, United Provinces, England, France, and Spain.[21] With the exception of a few etchings, Rubens left the printmaking to specialists, who included Lucas Vorsterman, Paulus Pontius and Willem Panneels.[22] He recruited a number of engravers trained by Christoffel Jegher, whom he carefully schooled in the more vigorous style he wanted. Rubens also designed the last significant woodcuts before the 19th-century revival in the technique.[23]

Marie de' Medici Cycle and diplomatic missions (1621–1630)

In 1621, the Queen Mother of France, Marie de' Medici, commissioned Rubens to paint two large allegorical cycles celebrating her life and the life of her late husband, Henry IV, for the Luxembourg Palace in Paris. The Marie de' Medici cycle (now in the Louvre) was installed in 1625, and although he began work on the second series it was never completed.[24] Marie was exiled from France in 1630 by her son, Louis XIII, and died in 1642 in the same house in Cologne where Rubens had lived as a child.[25]

.jpg.webp)

After the end of the Twelve Years' Truce in 1621, the Spanish Habsburg rulers entrusted Rubens with a number of diplomatic missions.[26] While in Paris in 1622 to discuss the Marie de' Medici cycle, Rubens engaged in clandestine information gathering activities, which at the time was an important task of diplomats. He relied on his friendship with Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc to get information on political developments in France.[27] Between 1627 and 1630, Rubens's diplomatic career was particularly active, and he moved between the courts of Spain and England in an attempt to bring peace between the Spanish Netherlands and the United Provinces. He also made several trips to the northern Netherlands as both an artist and a diplomat.

At the courts he sometimes encountered the attitude that courtiers should not use their hands in any art or trade, but he was also received as a gentleman by many. Rubens was raised by Philip IV of Spain to the nobility in 1624 and knighted by Charles I of England in 1630. Philip IV confirmed Rubens's status as a knight a few months later.[28] Rubens was awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree from Cambridge University in 1629.[29]

Rubens was in Madrid for eight months in 1628–1629. In addition to diplomatic negotiations, he executed several important works for Philip IV and private patrons. He also began a renewed study of Titian's paintings, copying numerous works including the Madrid Fall of Man (1628–29).[30] During this stay, he befriended the court painter Diego Velázquez and the two planned to travel to Italy together the following year. Rubens, however, returned to Antwerp and Velázquez made the journey without him.[31]

His stay in Antwerp was brief, and he soon travelled on to London where he remained until April 1630. An important work from this period is the Allegory of Peace and War (1629; National Gallery, London).[32] It illustrates the artist's lively concern for peace, and was given to Charles I as a gift.

While Rubens's international reputation with collectors and nobility abroad continued to grow during this decade, he and his workshop also continued to paint monumental paintings for local patrons in Antwerp. The Assumption of the Virgin Mary (1625–6) for the Cathedral of Antwerp is one prominent example.

Last decade (1630–1640)

Rubens's last decade was spent in and around Antwerp. Major works for foreign patrons still occupied him, such as the ceiling paintings for the Banqueting House at Inigo Jones's Palace of Whitehall, but he also explored more personal artistic directions.

In 1630, four years after the death of his first wife Isabella, the 53-year-old painter married his first wife's niece, the 16-year-old Hélène Fourment. Hélène inspired the voluptuous figures in many of his paintings from the 1630s, including The Feast of Venus (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), The Three Graces and The Judgement of Paris (both Prado, Madrid). In the latter painting, which was made for the Spanish court, the artist's young wife was recognized by viewers in the figure of Venus. In an intimate portrait of her, Hélène Fourment in a Fur Wrap, also known as Het Pelsken, Rubens's wife is even partially modelled after classical sculptures of the Venus Pudica, such as the Medici Venus.

In 1635, Rubens bought an estate outside Antwerp, the Steen, where he spent much of his time. Landscapes, such as his Château de Steen with Hunter (National Gallery, London) and Farmers Returning from the Fields (Pitti Gallery, Florence), reflect the more personal nature of many of his later works. He also drew upon the Netherlandish traditions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder for inspiration in later works like Flemish Kermis (c. 1630; Louvre, Paris).

Death

Rubens died from heart failure as a result of his chronic gout on 30 May 1640. He was interred in the Saint James' Church in Antwerp. A burial chapel for the artist and his family was built in the church. Construction on the chapel started in 1642 and was completed in 1650 when Cornelis van Mildert (the son of Rubens's friend, the sculptor Johannes van Mildert) delivered the altarstone. The chapel is a marble altar portico with two columns framing the altarpiece of the Virgin and child with saints painted by Rubens himself. The painting expresses the basic tenets of the Counter Reformation through the figures of the Virgin and saints. In the upper niche of the retable is a marble statue depicting the Virgin as the Mater Dolorosa whose heart is pierced by a sword, which was likely sculpted by Lucas Faydherbe, a pupil of Rubens. The remains of Rubens's second wife Helena Fourment and two of her children (one of which fathered by Rubens) were later also laid to rest in the chapel. Over the coming centuries about 80 descendants from the Rubens family were interred in the chapel.[33]

At the request of canon van Parijs, Rubens's epitaph, written in Latin by his friend Gaspar Gevartius, was chiselled on the chapel floor. In the tradition of the Renaissance, Rubens is compared in the epitaph to Apelles, the most famous painter of Greek Antiquity.[34][35]

Work

Feminist interpretation

His biblical and mythological nudes are especially well-known. Painted in the Baroque tradition of depicting women as soft-bodied, passive, and to the modern eye highly sexualized beings; his nudes emphasize the concepts of fertility, desire, physical beauty, temptation, and virtue. Skillfully rendered, these paintings of nude women are thought by feminists to have been created to sexually appeal to his largely male audience of patrons,[36] although the female nude as an example of beauty has been a traditional motif in European art for centuries. Additionally, Rubens was quite fond of painting full-figured women, giving rise to terms like 'Rubensian' or 'Rubenesque' (sometimes 'Rubensesque'). His large-scale cycle representing Marie de Medicis focuses on several classic female archetypes like the virgin, consort, wife, widow, and diplomatic regent.[37] The inclusion of this iconography in his female portraits, along with his art depicting noblewomen of the day, serve to elevate his female portrait sitters to the status and importance of his male portrait sitters.[37]

Rubens's depiction of males is equally stylized, replete with meaning, and quite the opposite of his female subjects. His male nudes represent highly athletic and large mythical or biblical men. Unlike his female nudes, most of his male nudes are depicted partially nude, with sashes, armour, or shadows shielding them from being completely unclothed. These men are twisting, reaching, bending, and grasping: all of which portrays his male subjects engaged in a great deal of physical, sometimes aggressive, action. The concepts Rubens artistically represents illustrate the male as powerful, capable, forceful and compelling. The allegorical and symbolic subjects he painted reference the classic masculine tropes of athleticism, high achievement, valour in war, and civil authority.[38] Male archetypes readily found in Rubens's paintings include the hero, husband, father, civic leader, king, and the battle weary.

Rubens was a great admirer of Leonardo da Vinci's work. Using an engraving done 50 years after Leonardo started his project on the Battle of Anghiari, Rubens did a masterly drawing of the Battle which is now in the Louvre in Paris. "The idea that an ancient copy of a lost artwork can be as important as the original is familiar to scholars," says Salvatore Settis, archaeologist and art historian.

Workshop

Paintings from Rubens's workshop can be divided into three categories: those he painted by himself, those he painted in part (mainly hands and faces), and copies supervised from his drawings or oil sketches. He had, as was usual at the time, a large workshop with many apprentices and students. It has not always been possible to identify who were Rubens's pupils and assistants since as a court painter Rubens was not required to register his pupils with the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke. About 20 pupils or assistants of Rubens have been identified, with various levels of evidence to include them as such. It is also not clear from surviving records whether a particular person was a pupil or assistant in Rubens's workshop or was an artist who was an independent master collaborating on specific works with Rubens. The unknown Jacob Moerman was registered as his pupil while Willem Panneels and Justus van Egmont were registered in the Guild's records as Rubens's assistants. Anthony van Dyck worked in Rubens's workshop after training with Hendrick van Balen in Antwerp. Other artists linked to the Rubens's workshop as pupils, assistants or collaborators are Abraham van Diepenbeeck, Lucas Faydherbe, Lucas Franchoys the Younger, Nicolaas van der Horst, Frans Luycx, Peter van Mol, Deodat del Monte, Cornelis Schut, Erasmus Quellinus the Younger, Pieter Soutman, David Teniers the Elder, Frans Wouters, Jan Thomas van Ieperen, Theodoor van Thulden and Victor Wolfvoet (II).[39]

He also often sub-contracted elements such as animals, landscapes or still-lifes in large compositions to specialists such as animal painters Frans Snyders and Paul de Vos, or other artists such as Jacob Jordaens. One of his most frequent collaborators was Jan Brueghel the Younger.

Art market

At a Sotheby's auction on 10 July 2002, Rubens's painting Massacre of the Innocents, rediscovered not long before, sold for £49.5 million (US$76.2 million) to Lord Thomson. At the end of 2013 this remained the record auction price for an Old Master painting. At a Christie's auction in 2012, Portrait of a Commander sold for £9.1 million (US$13.5 million) despite a dispute over the authenticity so that Sotheby's refused to auction it as a Rubens.[40]

Selected exhibitions

- 1936 Rubens and His Times, Paris.

- 1997 The Century of Rubens in French Collections, Paris.

- 2004 Rubens, Palais de Beaux-Arts, Lille.

- 2005 Peter Paul Rubens: The Drawings, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- 2015 Rubens and His Legacy, The Royal Academy, London.

- 2017 Rubens: The Power of Transformation, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

- 2019 Early Rubens, Art Gallery of Ontario Toronto, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.[41]

Lost works

Lost works by Rubens include:

- The Crucifixion, painted for the Church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, Rome, was imported to England in 1811. It was auctioned in 1812 and again in 1820 and 1821 but was lost at sea sometime after 1821.[42]

- Equestrian Portrait of the Archduke Albert

- Susannah and the Elders is now known only from engraving from 1620 by Lucas Vosterman.

- Satyr, Nymph, Putti and Leopards is now known only from engraving.

- Judith Beheading Holofernes c. 1609 known only through the 1610 engraving by Cornelis Galle the Elder.

- Works destroyed in the bombardment of Brussels included:

- Madonna of the Rosary painted for the Royal Chapel of the Dominican Church

- Virgin Adorned with Flowers by Saint Anne, 1610 painted for the Church of the Carmelite Friars

- Saint Job Triptych, 1613, painted for Saint Nicholas Church

- Cambyses Appointing Otanes Judge, Judgment of Solomon, and Last Judgment, all for the Magistrates' Hall

- In the Coudenberg Palace fire there were several works by Rubens destroyed, like Nativity (1731), Adoration of the Magi and Pentecost.[43]

- The paintings Neptune and Amphitrite, Vision of Saint Hubert and Diana and Nymphs Surprised by Satyrs was destroyed in the Friedrichshain flak tower fire in 1945.[44]

- The painting The Abduction of Proserpine was destroyed in the fire at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire, 5 February 1861.[45]

- The painting Crucifixion with Mary, St. John, Magdalen, 1643 was destroyed in the English Civil War by Parliamentarians in the Queen's Chapel, Somerset House, London, 1643[46]

- The painting Equestrian Portrait of Philip IV of Spain was destroyed in the fire at Royal Alcázar of Madrid fire in 1734. A copy is in the Uffizi Gallery.

- The Continence of Scipio was destroyed in a fire in the Western Exchange, Old Bond Street, London, March 1836[47]

- The painting The Lion Hunt was removed by Napoleon's agents from Schloss Schleissheim, near Munich, 1800 and was destroyed later in a fire at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux.[48]

- An alleged Rubens painting Portrait of a Girl reported to have been in the collection of Alexander Dumas was reported lost in a fire.[49]

- The painting Equestrian Portrait of the Duke of Buckingham (1625) and the ceiling painting The Duke of Buckingham Triumphing over Envy and Anger (circa 1625), both later owned by the Earl of Jersey at Osterley Park, were destroyed in a fire at the Le Gallais depository in St Helier, Jersey, on 30 September 1949.[50]

- Portrait of Philip IV of Spain from 1628 was destroyed in the incendiary attack at the Kunsthaus Zürich in 1985.[51]

- Portrait of George Villiers, c. 1625. This painting that had been deemed lost for nearly 400 years was rediscovered in 2017 in Pollok House, Glasgow, Scotland. Conservation treatment carried out by Simon Rollo Gillespie helped to demonstrate that the work was not a later copy by a lesser artist but was the original by the hand of the master himself.[52][53][54]

Works

- Early paintings

.jpg.webp) Equestrian portrait of the Duke of Lerma, 1603, Prado Museum

Equestrian portrait of the Duke of Lerma, 1603, Prado Museum.jpg.webp) The Judgement of Paris, c. 1606 Museo del Prado

The Judgement of Paris, c. 1606 Museo del Prado.JPG.webp) Portrait of a Young Woman with a Rosary, 1609–10, oil on wood, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

Portrait of a Young Woman with a Rosary, 1609–10, oil on wood, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum Venus at the Mirror, 1613–14

Venus at the Mirror, 1613–14 Diana Returning from Hunt, 1615, oil on canvas, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

Diana Returning from Hunt, 1615, oil on canvas, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus, c. 1617, oil on canvas, Alte Pinakothek

The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus, c. 1617, oil on canvas, Alte Pinakothek

- Historical portraits

Portrait of Marchesa Brigida Spinola-Doria, 1606

Portrait of Marchesa Brigida Spinola-Doria, 1606.jpg.webp) Portrait of King Philip IV of Spain, c. 1628–29

Portrait of King Philip IV of Spain, c. 1628–29 Portrait of Elisabeth of France. 1628, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Portrait of Elisabeth of France. 1628, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna Portrait of Ambrogio Spinola, c. 1627, National Gallery in Prague

Portrait of Ambrogio Spinola, c. 1627, National Gallery in Prague Portrait of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, c. 1617–1628, Pollok House

Portrait of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, c. 1617–1628, Pollok House Sketch for Equestrian Portrait of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 1625, Kimbell Art Museum

Sketch for Equestrian Portrait of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 1625, Kimbell Art Museum Portrait of King Władysław IV Vasa of Poland, 1620s, Wawel Royal Castle National Art Collection

Portrait of King Władysław IV Vasa of Poland, 1620s, Wawel Royal Castle National Art Collection

- Landscapes

Landscape with the Ruins of Mount Palatine in Rome, 1615

Landscape with the Ruins of Mount Palatine in Rome, 1615 Miracle of Saint Hubert, painted together with Jan Bruegel, 1617

Miracle of Saint Hubert, painted together with Jan Bruegel, 1617 Landscape with Milkmaids and Cattle, 1618

Landscape with Milkmaids and Cattle, 1618 The Château Het Steen with Hunter, c. 1635–1638, National Gallery, London

The Château Het Steen with Hunter, c. 1635–1638, National Gallery, London

- Mythological

Venus, Cupid, Bacchus and Ceres, 1612

Venus, Cupid, Bacchus and Ceres, 1612 Jupiter and Callisto, 1613, Museumslandschaft of Hesse in Kassel

Jupiter and Callisto, 1613, Museumslandschaft of Hesse in Kassel%253B_Peter_Paul_Rubens.jpg.webp) Pythagoras Advocating Vegetarianism, 1618–1630, by Rubens and Frans Snyders, inspired by Pythagoras's speech in Ovid's Metamorphoses, Royal Collection

Pythagoras Advocating Vegetarianism, 1618–1630, by Rubens and Frans Snyders, inspired by Pythagoras's speech in Ovid's Metamorphoses, Royal Collection.jpg.webp) Perseus and Andromeda, c. 1622, Hermitage Museum

Perseus and Andromeda, c. 1622, Hermitage Museum Ermit and sleeping Angelica, 1628

Ermit and sleeping Angelica, 1628 Perseus Liberating Andromeda, 1639–40, Museo del Prado

Perseus Liberating Andromeda, 1639–40, Museo del Prado_Peace_and_War_(1629).jpg.webp) Minerva Protecting Peace from Mars, 1629–1630, The National Gallery, London

Minerva Protecting Peace from Mars, 1629–1630, The National Gallery, London_-_P.P._Rubens.jpg.webp) Bacchanalia scene with nymphs and satyrs (detail of The feast of Venus Verticordia, 1635–36) Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna

Bacchanalia scene with nymphs and satyrs (detail of The feast of Venus Verticordia, 1635–36) Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna The Three Graces, 1635, Prado

The Three Graces, 1635, Prado.jpg.webp) Diana and her Nymphs surprised by the Fauns, c. 1639–40, Prado Museum

Diana and her Nymphs surprised by the Fauns, c. 1639–40, Prado Museum Venus and Adonis, 1635–1638, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Venus and Adonis, 1635–1638, Metropolitan Museum of Art_01.jpg.webp) King Ixion fooled by Juno, whom he wanted to seduce (Louvre Museum)

King Ixion fooled by Juno, whom he wanted to seduce (Louvre Museum) The Birth of the Milky Way, c. 1637, Prado Museum

The Birth of the Milky Way, c. 1637, Prado Museum

- Helena Fourment and related pictures

Rubens with Hélène Fourment and their son Peter Paul, 1639, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rubens with Hélène Fourment and their son Peter Paul, 1639, Metropolitan Museum of Art_-_Alte_Pinakothek_-_Munich_-_Germany_2017.jpg.webp) Helena Fourment in Wedding Dress, detail, the artist's second wife, c. 1630, Alte Pinakothek

Helena Fourment in Wedding Dress, detail, the artist's second wife, c. 1630, Alte Pinakothek Bathsheba at the Fountain, 1635

Bathsheba at the Fountain, 1635 Pastoral Scene, 1636

Pastoral Scene, 1636

Drawings

The Night, 1601–1603, black chalk and gouache on paper (after Michelangelo), Louvre-Lens

The Night, 1601–1603, black chalk and gouache on paper (after Michelangelo), Louvre-Lens Man in Korean Costume, c. 1617, black chalk with touches of red chalk, J. Paul Getty Museum

Man in Korean Costume, c. 1617, black chalk with touches of red chalk, J. Paul Getty Museum Peter Paul Rubens (possibly his self-portrait), c. 1620s

Peter Paul Rubens (possibly his self-portrait), c. 1620s Young Woman with Folded Hands, c. 1629–30, red and black chalk, heightened with white, Boijmans Van Beuningen

Young Woman with Folded Hands, c. 1629–30, red and black chalk, heightened with white, Boijmans Van Beuningen Study of Three Women (Psyche and her sisters), c. 1635, sanguine and ink on paper, Warsaw University Library

Study of Three Women (Psyche and her sisters), c. 1635, sanguine and ink on paper, Warsaw University Library Study for a St. Mary Magdalen, date unknown, British Museum

Study for a St. Mary Magdalen, date unknown, British Museum

- Biblical Scenes

Susanna and the elders, 1609–1610, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando

Susanna and the elders, 1609–1610, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando Jan Brueghel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens, The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man, Mauritshuis, The Hague

Jan Brueghel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens, The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man, Mauritshuis, The Hague Lot and his daughters, c. 1613–14

Lot and his daughters, c. 1613–14 The Holy Trinity, Kunstmuseum Basel

The Holy Trinity, Kunstmuseum Basel Christ Triumphant over Sin and Death, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg

Christ Triumphant over Sin and Death, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg

Notes

- "Rubens". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Weststeijn, T. (2008). The Visible world: Samuel van Hoogstraten's art theory and the legitimation of painting in the Dutch Golden Age. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978 90 8964 027 7.

- Nico Van Hout, Functies van doodverf met bijzondere aandacht voor de onderschildering en andere onderliggende stadia in het werk van P. P. Rubens, PHD thesis Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 2005. (in Dutch).

- Giulio Girondi, Frans Geffels, Rubens and the Palazzi di Genova, pp. 183–199.

- Joost vander Auwera, Arnout Balis, Rubens: A Genius at Work : the Works of Peter Paul Rubens in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium Reconsidered, Lannoo Uitgeverij, 2007, p. 33.

- H. C. Erik Midelfort, "Mad Princes of Renaissance Germany", page 58, University of Virginia Press, 22 January 1996. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Belkin (1998): 11–18.

- Held (1983): 14–35.

- Belkin (1998): 22–38.

- Noyes, Ruth S. (2017). Peter Paul Rubens and the Counter-Reformation Crisis of the Beati moderni. Routledge. ISBN 9781351613200.

- Belkin (1998): 42; 57.

- Belkin (1998): 52–57

- Belkin (1998): 59.

- Sirjacobs, Raymond. Antwerpen Sint-Pauluskerk: Rubens En De Mysteries Van De Rozenkrans = Rubens Et Les Mystères Du Rosaire = Rubens and the Mysteries of the Rosary, Antwerpen: Sint-Paulusvrienden, 2004

- Rosen, Mark (2008). "The Medici Grand Duchy and Rubens' First Trip to Spain". Oud Holland (Vol. 121, No. 2/3): 147–152. doi:10.1163/187501708787335857.

- Belkin (1998): 71–73

- Belkin (1998): 75.

- Jaffé (1977): 85–99; Belting (1994): 484–90, 554–56.

- Belkin (1998): 95.

- Martin (1977): 109.

- Hottle, Andrew D. (2004). "Commerce and Connections: Peter Paul Rubens and the Dedicated Print". Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek. 55: 54–85. doi:10.1163/22145966-90000105.

- Pauw-De Veen (1977): 243–251.

- A Hyatt Mayor, Prints and People, Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, no.427–32, ISBN 0-691-00326-2

- Belkin (1998): 175; 192; Held (1975): 218–233, esp. pp. 222–225.

- Belkin (1998): 173–175.

- Belkin (1998): 199–228.

- Auwers: p. 25.

- Auwers: p. 32.

- Belkin (1998): 339–340

- Belkin (1998): 210–218.

- Belkin (1998): 217–218.

- "Minerva protects Pax from Mars ('Peace and War')". The National Gallery. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- Jeffrey Muller, St. Jacob's Antwerp Art and Counter Reformation in Rubens's Parish Church, BRILL, 2016, pp. 359-364

- Antwerpen – Parochiekerken; 1. Afdeeling, Volume 1

- Full text of the epitaph reads as follows: "D.O.M./PETRVS PAVLVS RVBENIVS eques/IOANNIS, huius urbis senatoris/flfius steini Toparcha:/qui inter cæteras quibus ad miraculum/excelluit doctrinæ historiæ priscæ/omniumq. bonarum artiu. et elegantiaru. dotes/ non sui tantum sæculi,/ sed et omnes ævi/ Appeles dicit meruit:/atque ad Regum Principumq. Virorum amicitias/gradum sibi fecit:/a. PHILIPPO IV. Hispaniarum Indiarumq. Rege / inter Sanctioris Concilli scribas Adscitus,/ et ad CAROLVM Magmnæ Brittaniæ Regem/Anno M.DC.XXIX. delegatus,/pacis inter eosdem principes mox initæ/fundamenta filiciter posuit./ Obiit anno sal. M.DC.XL.XXX. May ætatis LXIV. Hoc momumenteum a Clarissimo GEVARTIO/olim PETRO PAVLO RVBENIO consecratum/ a Posteris huc usque neglectum,/ Rubeniana stirpe Masculina jam inde extincta/ hoc anno M.DCC.LV. Poni Curavit./ R.D. JOANNES BAPT. JACOBVS DE PARYS. Hujus insignis Eccelsiæ Canonicus/ ex matre et avia Rubenia nepos./ R.I.P." ("In honor of the good and all-powerful God. Peter Paul Rubens, knight, son of Jan, alderman of this city and Lord of Steen, who, apart from his other talents, through which he excelled miraculously in the knowledge of (old) history and of all (useful) noble and beautiful arts, also deserved the glorious name of Apelles, of his time as of all centuries, and who gained the friendship of kings and princes, was elevated to the dignity of writer of the Secret Council; and was sent by Philip IV, King of Spain and India, as his envoy to Charles, King of Great Britain, in 1629, (fortunately) laid the foundations for peace, which was soon made between the two monarchs. He died in the year of the Lord 1640, 30 May, at the age of 64. May he rest in peace")

- "Sally Markowitz, Review of The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality by Lynda Nead] The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism Vol. 53, No. 2 (Spring, 1995), pp. 216-218". JSTOR 431556.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Cohen, Sarah R. (2003). "Rubens's France: Gender and Personification in the Marie de Médicis Cycle". The Art Bulletin. 85 (3): 490–522. doi:10.2307/3177384. JSTOR 3177384.

- "Gender in Art – Dictionary definition of Gender in Art | Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- Balis, A, Rubens and his Studio: Defining the Problem. in Rubens: a Genius at Work. Rubens: a Genius at Work, Warnsveld (Lannoo), 2007, pp. 30-51

- Art historians cast doubt over Earl Spencer's £9m Rubens, The Independent, 11 July 2010

- "Early Rubens".

- Smith, John (1830), A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters: Peter Paul Rubens, Smith

- Joost vander Auwera (2007), Rubens, l'atelier du génie, Lannoo Uitgeverij, p. 14, ISBN 978-90-209-7242-9

- John Smith, A catalogue raisonne of the works of the most eminent (...) (1830), p. 153. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- The Annual Register, Or, A View of the History, Politics, and Literature for the Year ..., J. Dodsley, 1862, p. 18

- Albert J. Loomie, "A Lost Crucifixion by Rubens", The Burlington Magazine Vol. 138, No. 1124 (November 1996). Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- W. Pickering, The Gentleman's Magazine vol. 5 (1836), p. 590.

- Barnes, An examination of Hunting Scenes by Peter Paul Rubens (2009), p.34. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "San Francisco Call 26 January 1908". California Digital Newspaper Collection. University of California, Riverside.

- Sutton, Peter C. (2004), Drawn by the Brush: Oil Sketches by Peter Paul Rubens, Yale University Press, p. 144, ISBN 978-0-300-10626-8

- Goss, Steven (2001), "A Partial Guide to the Tools of Art Vandalism", Cabinet Magazine (3)

- Slawson, Nicola (24 September 2017). "Lost Rubens portrait of James I's 'lover' is rediscovered in Glasgow". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- Latil, Lucas (27 September 2017). "Un Rubens, perdu depuis 400 ans, aurait été retrouvé en Écosse". Le Figaro.

- Xinhua (26 September 2017). "Rubens' long-lost masterpiece exhibited in gallery as copy". China Daily.

Sources

- Auwers, Michael, Pieter Paul Rubens als diplomatiek debutant. Het verhaal van een ambitieus politiek agent in de vroege zeventiende eeuw, in: Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis – 123e jaargang, nummer 1, p. 20–33 (in Dutch)

- Belkin, Kristin Lohse (1998). Rubens. Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-3412-2.

- Belting, Hans (1994). Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-04215-4.

- Evers, Hans Gerhard: Peter Paul Rubens. F. Bruckmann, Munich 1942, 528 pages, 272 images, 4 color plates (Flemish edition at De Sikkel, Antwerp 1946). (Information on the book and download link)

- Evers, Hans Gerhard: Rubens und sein Werk. Neue Forschungen. De Lage Landen, Brussels 1943. 383 pages and plates (information on the book and download link)

- Held, Julius S. (1975) "On the Date and Function of Some Allegorical Sketches by Rubens." In: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. Vol. 38: 218–233.

- Held, Julius S. (1983) "Thoughts on Rubens' Beginnings." In: Ringling Museum of Art Journal: 14–35. ISBN 0-916758-12-5.

- Jaffé, Michael (1977). Rubens and Italy. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1064-9.

- Martin, John Rupert (1977). Baroque. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-430077-3.

- Mayor, A. Hyatt (1971). Prints and People. Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton. ISBN 0-691-00326-2.

- Pauw-De Veen, Lydia de. "Rubens and the graphic arts". In: Connoisseur CXCV/786 (Aug 1977): 243–251.

Further reading

- Alpers, Svetlana. The Making of Rubens. New Haven 1995.

- Heinen, Ulrich, "Rubens zwischen Predigt und Kunst." Weimar 1996.

- Baumstark, Reinhold (1985). Peter Paul Rubens: the Decius Mus cycle. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-394-1.

- Büttner, Nils, Herr P. P. Rubens. Göttingen 2006.

- Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard. An Illustrated Catalogue Raisonne of the Work of Peter Paul Rubens Based on the Material Assembled by the Late Dr. Ludwig Burchard in Twenty-Seven Parts, Edited by the Nationaal Centrum Voor de Plastische Kunsten Van de XVI en de XVII Eeuw.

- Lamster, Mark. Master of Shadows, The Secret Diplomatic Career of Peter Paul Rubens New York, Doubleday, 2009.

- Lilar, Suzanne, Le Couple (1963), Paris, Grasset; Reedited 1970, Bernard Grasset Coll. Diamant, 1972, Livre de Poche; 1982, Brussels, Les Éperonniers, ISBN 2-87132-193-0; Translated as Aspects of Love in Western Society in 1965, by and with a foreword by Jonathan Griffin, New York, McGraw-Hill, LC 65-19851.

- Sauerlander, Willibald. The Catholic Rubens: Saints and Martyrs (Getty Research Institute; 2014); 311 pages; looks at his altarpieces in the context of the Counter-Reformation.

- Schrader, Stephanie, Looking East: Ruben's Encounter with Asia, Getty Publications, Los Angeles, 2013. ISBN 978-1-60606-131-2

- Vlieghe, Hans, Flemish Art and Architecture 1585–1700, Yale University Press, Pelican History of Art, New Haven and London, 1998. ISBN 0-300-07038-1