Blenheim Palace

Blenheim Palace (pronounced /ˈblɛnɪm/ BLEN-im[1]) is a country house in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, England. It is the seat of the Dukes of Marlborough and the only non-royal, non-episcopal country house in England to hold the title of palace. The palace, one of England's largest houses, was built between 1705 and 1722, and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.[2]

The palace is named after the 1704 Battle of Blenheim. It was originally intended to be a reward to John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough for his military triumphs against the French and Bavarians in the War of the Spanish Succession, culminating in the Battle of Blenheim. The land was given as a gift, and construction began in 1705, with some financial support from Queen Anne. The project soon became the subject of political infighting, with the Crown cancelling further financial support in 1712, Marlborough's three-year voluntary exile to the Continent, the fall from influence of his duchess, and lasting damage to the reputation of the architect Sir John Vanbrugh.

Designed in the rare, and short-lived, English Baroque style, architectural appreciation of the palace is as divided today as it was in the 1720s.[3] It is unique in its combined use as a family home, mausoleum and national monument. The palace is notable as the birthplace and ancestral home of Sir Winston Churchill.

Following the palace's completion, it became the home of the Churchill (later Spencer-Churchill) family for the next 300 years, and various members of the family have wrought changes to the interiors, park and gardens. At the end of the 19th century, the palace was saved from ruin by funds gained from the 9th Duke of Marlborough's marriage to American railroad heiress Consuelo Vanderbilt.

Churchills

John Churchill was born in Devon. Although his family had aristocratic relations, it belonged to the minor gentry rather than the upper echelons of 17th-century society. In 1678, Churchill married Sarah Jennings,[4] and in April that year, he was sent by Charles II to The Hague to negotiate a convention on the deployment of the English army in Flanders. The mission ultimately proved abortive. In May, Churchill was appointed to the temporary rank of Brigadier-General of Foot, but the possibility of a continental campaign was eliminated with the Treaty of Nijmegen.[5]

When Churchill returned to England, the Popish Plot resulted in a temporary three-year banishment for James Stuart, Duke of York. The Duke obliged Churchill to attend him, first to The Hague, then in Brussels.[6] For his services during the crisis, Churchill was made Lord Churchill of Eyemouth in the peerage of Scotland in 1682, and the following year appointed colonel of the King's Own Royal Regiment of Dragoons.[7]

On the death of Charles II in 1685, his brother, the Duke of York, became King James II. James had been Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company (today North America's oldest company, established by royal charter in 1670), and with his succession to the throne, Churchill was appointed the company's third ever governor. He had also been affirmed Gentleman of the Bedchamber in April, and admitted to the English peerage as Baron Churchill of Sandridge in the county of Hertfordshire in May. Following the Monmouth Rebellion, Churchill was promoted to Major General and awarded the lucrative colonelcy of the Third Troop of Life Guards.[8]

When William, Prince of Orange, invaded England in November 1688, Churchill, accompanied by some 400 officers and men, rode to join him in Axminster.[9] When the King saw he could not even keep Churchill—for so long his loyal and intimate servant—he fled to France.[10] As part of William III's coronation honours, Churchill was created Earl of Marlborough, sworn to the Privy Council, and made a Gentleman of the King's Bedchamber.[11]

During the War of the Spanish Succession Churchill gained a reputation as a capable military commander, and in 1702 he was elevated to the dukedom of Marlborough. During the war he won a series of victories, including the Battle of Blenheim (1704), the Battle of Ramillies (1706), the Battle of Oudenarde (1708), and the Battle of Malplaquet (1709). For his victory at Blenheim, the Crown bestowed upon Marlborough the tenancy of the royal manor of Hensington (situated on the site of Woodstock) to site the new palace, and Parliament voted a substantial sum of money towards its creation. The rent or petit serjeanty due to the Crown for the land was set at the peppercorn rent or quit-rent of one copy of the French royal flag to be tendered to the Monarch annually on the anniversary of the Battle of Blenheim. This flag is displayed by the Monarch on a 17th-century French writing table in Windsor Castle.[12]

Marlborough's wife was by all accounts a cantankerous woman, though capable of great charm. She had befriended the young Princess Anne and later, when the princess became Queen, the Duchess of Marlborough, as Her Majesty's Mistress of the Robes, exerted great influence over the Queen on both personal and political levels. The relationship between Queen and Duchess later became strained and fraught, and following their final quarrel in 1711, the money for the construction of Blenheim ceased.[13] For political reasons the Marlboroughs went into exile on the Continent until they returned the day after the Queen's death on 1 August 1714.[11]

Site

The estate given by the nation to Marlborough for the new palace was the manor of Woodstock, sometimes called the Palace of Woodstock, which had been a royal demesne, in reality little more than a deer park.[14] Legend has obscured the manor's origins. King Henry I enclosed the park to contain the deer. Henry II housed his mistress Rosamund Clifford (sometimes known as "Fair Rosamund") there in a "bower and labyrinth"; a spring in which she is said to have bathed remains, named after her.[14]

It seems the unostentatious hunting lodge was rebuilt many times, and had an uneventful history until Elizabeth I, before her succession, was imprisoned there by her half-sister Mary I between 1554 and 1555.[14] Elizabeth had been implicated in the Wyatt plot, but her imprisonment at Woodstock was short, and the manor remained in obscurity until bombarded and ruined by Oliver Cromwell's troops during the Civil War.[14]

When the park was being re-landscaped as a setting for the Palace, the 1st Duchess wanted the historic ruins demolished, while Vanbrugh, an early conservationist, wanted them restored and made into a landscape feature. The Duchess, as so often in her disputes with her architect, won the day and the remains of the manor were swept away.[14]

Architect

The architect selected for the ambitious project was a controversial one. The Duchess was known to favour Sir Christopher Wren, famous for St Paul's Cathedral and many other national buildings. The Duke however, following a chance meeting at a playhouse, is said to have commissioned Sir John Vanbrugh there and then. Vanbrugh, a popular dramatist, was an untrained architect, who usually worked in conjunction with the trained and practical Nicholas Hawksmoor. The duo had recently completed the first stages of the Baroque Castle Howard. This huge Yorkshire mansion was one of England's first houses in the flamboyant European Baroque style. The success of Castle Howard led Marlborough to commission something similar at Woodstock.[15]

Blenheim, however, was not to provide Vanbrugh with the architectural plaudits he imagined it would. The fight over funding led to accusations of extravagance and impracticality of design, many of these charges levelled by the Whig factions in power. He found no defender in the Duchess of Marlborough. Having been foiled in her wish to employ Wren,[16] she levelled criticism at Vanbrugh on every level, from design to taste. In part their problems arose from what was demanded of the architect. The nation (which was then assumed, by both architect and owners, to be paying the bills) wanted a monument, but the Duchess wanted not only a fitting tribute to her husband but also a comfortable home, two requirements that were not compatible in 18th-century architecture. Finally, in the early days of the building the Duke was frequently away on his military campaigns, and it was left to the Duchess to negotiate with Vanbrugh. More aware than her husband of the precarious state of the financial aid they were receiving, she criticised Vanbrugh's grandiose ideas for their extravagance.[17]

Following their final altercation, Vanbrugh was banned from the site. In 1719, whilst the Duchess was away, Vanbrugh viewed the palace in secret. However, when Vanbrugh's wife visited the completed Blenheim as a member of the viewing public in 1725, the Duchess refused to allow her even to enter the park.[18]

Vanbrugh's severe massed Baroque used at Blenheim never truly caught the public imagination, and was quickly superseded by the revival of the Palladian style. Vanbrugh's reputation was irreparably damaged, and he received no further truly great public commissions. For his final design, Seaton Delaval Hall in Northumberland, which was hailed as his masterpiece, he used a refined version of the Baroque employed at Blenheim. He died shortly before its completion.[18]

Funding the construction

The precise responsibility for the funding of the new palace has always been a debatable subject, unresolved to this day. The palace as a reward was mooted within months of the Battle of Blenheim, at a time when Marlborough was still to gain many further victories on behalf of the country. That a grateful nation led by Queen Anne wished and intended to give their national hero a suitable home is beyond doubt, but the exact size and nature of that house is questionable. A warrant dated 1705, signed by the parliamentary treasurer the Earl of Godolphin, appointed Vanbrugh as architect and outlined his remit. Unfortunately for the Churchills, nowhere did this warrant mention Queen or Crown.[19]

The Duke of Marlborough contributed £60,000 to the initial cost when work commenced in 1705, which, supplemented by Parliament, should have built a monumental house. Parliament voted funds for the building of Blenheim, but no exact sum was mentioned nor provision for inflation or over-budget expenses. Almost from the outset, funds were spasmodic. Queen Anne paid some of them, but with growing reluctance and lapses, following her frequent altercations with the Duchess. After their final argument in 1712, all state money ceased and work came to a halt. £220,000 had already been spent and £45,000 was owing to workmen. The Marlboroughs were forced into exile on the continent, and did not return until after the Queen's death in 1714.[11]

On their return the Duke and Duchess came back into favour at court. The 64-year-old Duke now decided to complete the project at his own expense. In 1716 work resumed, but the project relied completely upon the limited means of the Duke himself. Harmony on the building site was short-lived, as in 1717 the Duke suffered a severe stroke, and the thrifty Duchess took control. The Duchess blamed Vanbrugh entirely for the growing costs and extravagance of the palace, the design of which she had never liked. Following a meeting with the Duchess, Vanbrugh left the building site in a rage, insisting that the new masons, carpenters and craftsmen, brought in by the Duchess, were inferior to those he had employed. The master craftsmen he had patronised, however, such as Grinling Gibbons, refused to work for the lower rates paid by the Marlboroughs. The craftsmen brought in by the Duchess, under the guidance of furniture designer James Moore, and Vanbrugh's assistant architect Hawksmoor, completed the work in perfect imitation of the greater masters.[19]

"Under the auspices of a munificent sovereign this house was built for John Duke of Marlborough, and his Duchess Sarah, by Sir J Vanbrugh between the years 1705 and 1722, and the Royal Manor of Woodstock, together with a grant of £240,000 towards the building of Blenheim, was given by Her Majesty Queen Anne and confirmed by act of Parliament . . . to the said John Duke of Marlborough and to all his issue male and female lineally descending."

—Plaque above the East gate of Blenheim Palace

Following the Duke's death in 1722, completion of the palace and its park became the Duchess's driving ambition. Vanbrugh's assistant Hawksmoor was recalled and in 1723 designed the "Arch of Triumph", based on the Arch of Titus, at the entrance to the park from Woodstock. Hawksmoor also completed the interior design of the library, the ceilings of many of the state rooms and other details in numerous other minor rooms, and various outbuildings.[20]

Cutting rates of pay to workmen, and using lower-quality materials in unobtrusive places, the widowed Duchess completed the great house as a tribute to her late husband. The final date of completion is not known, but as late as 1735 the Duchess was haggling with Rysbrack over the cost of Queen Anne's statue placed in the library. In 1732 the Duchess wrote "The Chappel is finish'd and more than half the Tomb there ready to set up".[21]

Design and architecture

Vanbrugh planned Blenheim in perspective; that is, to be best viewed from a distance. As the site covers some seven acres (28,000 m2) this is also a necessity.[22]

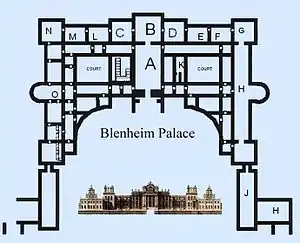

The plan of the palace's principal block (or corps de logis) is a rectangle (see plan) pierced by two courtyards; these serve as little more than light wells. Contained behind the southern facade are the principal state apartments; on the east side are the suites of private apartments of the Duke and Duchess, and on the west along the entire length of the piano nobile is given a long gallery originally conceived as a picture gallery, but is now the library. The corps de logis is flanked by two further service blocks around square courtyards (not shown in the plan). The east court contains the kitchens, laundry, and other domestic offices, the west court adjacent to the chapel the stables and indoor riding school. The three blocks together form the "Great Court" designed to overpower the visitor arriving at the palace. Pilasters and pillars abound, while from the roofs, themselves resembling those of a small town, great statues in the Renaissance manner of St Peter's in Rome gaze down on the visitor below, who is rendered inconsequential. Other assorted statuary in the guise of martial trophies decorate the roofs, most notably Britannia standing atop the entrance pediment in front of two reclining chained French captives sculpted in the style of Michelangelo,[23] and the English lion devouring the French cock, on the lower roofs. Many of these are by such masters as Grinling Gibbons.[24]

In the design of great 18th-century houses comfort and convenience were subservient to magnificence, and this is certainly the case at Blenheim. This magnificence over creature comfort is heightened as the architect's brief was to create not only a home but also a national monument to reflect the power and civilisation of the nation. To create this monumental effect, Vanbrugh chose to design in a severe Baroque style, using great masses of stone to imitate strength and create shadow as decoration.[25]

The solid and huge entrance portico on the north front resembles more the entrance to a pantheon than a family home. Vanbrugh also liked to employ what he called his "castle air", which he achieved by placing a low tower at each corner of the central block and crowning the towers with vast belvederes of massed stone, decorated with curious finials (disguising the chimneys). Coincidentally these towers, which hint at the pylons of an Egyptian temple, further add to the heroic pantheonesque atmosphere of the building.[26]

There are two approaches to the palace's grand entrance, one from the long straight drive through wrought iron gates directly into the Great Court; the other, equally if not more impressive, betrays Vanbrugh's true vision: the palace as a bastion or citadel, the true monument and home to a great warrior. Piercing the windowless, city-like curtain wall of the east court is the great East Gate, a monumental triumphal arch, more Egyptian in design than Roman. An optical illusion was created by tapering its walls to create an impression of even greater height. Confounding those who accuse Vanbrugh of impracticality, this gate is also the palace's water tower. Through the arch of the gate one views across the courtyard a second equally massive gate, that beneath the clock tower,[27] through which one glimpses the Great Court.[28]

.jpg.webp)

This view of the Duke as an omnipotent being is also reflected in the interior design of the palace, and indeed its axis to certain features in the park. It was planned that when the Duke dined in state in his place of honour in the great saloon, he would be the climax of a great procession of architectural mass aggrandising him rather like a proscenium. The line of celebration and honour of his victorious life began with the great column of victory surmounted by his statue and detailing his triumphs, and the next point on the great axis, planted with trees in the position of troops, was the epic Roman style bridge. The approach continues through the great portico into the hall, its ceiling painted by James Thornhill with the Duke's apotheosis, then on under a great triumphal arch, through the huge marble door-case with the Duke's marble effigy above it (bearing the ducal plaudit "Nor could Augustus better calm mankind"), and into the painted saloon, the most highly decorated room in the palace, where the Duke was to have sat enthroned.[29]

The Duke was to have sat with his back to the great 30-tonne marble bust of his vanquished foe Louis XIV, positioned high above the south portico. Here the defeated King was humiliatingly forced to look down on the great parterre and spoils of his conqueror (rather in the same way as severed heads were displayed generations earlier). The Duke did not live long enough to see this majestic tribute realised, and sit enthroned in this architectural vision. The Duke and Duchess moved into their apartments on the eastern side of the palace, but the entirety was not completed until after the Duke's death.[30]

The palace has been Grade I listed on the National Heritage List for England since August 1957.[31]

Palace chapel

The palace chapel, as a consequence of the Duke's death, now obtained even greater importance. The design was altered by the Marlboroughs' friend the Earl of Godolphin, who placed the high altar in defiance of religious convention against the west wall, thus allowing the dominating feature to be the Duke's gargantuan tomb and sarcophagus. Commissioned by the Duchess in 1730, it was designed by William Kent, and statues of the Duke and Duchess depicted as Caesar and Caesarina adorn the great sarcophagus. In bas relief at the base of the tomb, the Duchess ordered to be depicted the surrender of Marshal Tallard. However, the theme throughout the palace of honouring the Duke did not reach its apotheosis until the dowager duchess's death in 1744. Then, the Duke's coffin was returned to Blenheim from its temporary resting place, Westminster Abbey, and husband and wife were interred together and the tomb erected and completed.[32] Now Blenheim had indeed become a pantheon and mausoleum. Successive Dukes and their wives are also interred in the vault beneath the chapel. Other members of family are interred in St. Martin's parish churchyard at Bladon, a short distance from the palace.[33]

Interior

.jpg.webp)

The internal layout of the rooms of the central block at Blenheim was defined by the court etiquette of the day. State apartments were designed as an axis of rooms of increasing importance and public use, leading to the chief room. The larger houses, like Blenheim, had two sets of state apartments each mirroring each other. The grandest and most public and important was the central saloon ("B" in the plan) which served as the communal state dining room. To either side of the saloon are suites of state apartments, decreasing in importance but increasing in privacy: the first room ("C") would have been an audience chamber for receiving important guests, the next room ("L") a private withdrawing room, the next room ("M") would have been the bedroom of the occupier of the suite, thus the most private. One of the small rooms between the bedroom and the internal courtyard was intended as a dressing room. This arrangement is reflected on the other side of the saloon. The state apartments were intended for use by only the most important guests such as a visiting sovereign. On the left (east) side of the plan on either side of the bow room (marked "O") can be seen a smaller but nearly identical layout of rooms, which were the suites of the Duke and Duchess themselves. Thus, the bow room corresponds exactly to the saloon in terms of its importance to the two smaller suites.[34]

Blenheim Palace was the birthplace of the 1st Duke's famous descendant, Winston Churchill, whose life and times are commemorated by a permanent exhibition in the suite of rooms in which he was born (marked "K" on the plan). Blenheim Palace was designed with all its principal and secondary rooms on the piano nobile, thus there is no great staircase of state: anyone worthy of such state would have no cause to leave the piano nobile. Insofar as Blenheim does have a grand staircase, it is the series of steps in the Great Court which lead to the North Portico. There are staircases of various sizes and grandeur in the central block, but none are designed on the same scale of magnificence as the palace. James Thornhill painted the ceiling of the hall in 1716. It depicts Marlborough kneeling to Britannia and proffering a map of the Battle of Blenheim. The hall is 67 ft (20 m) high, and remarkable chiefly for its size and for its stone carvings by Gibbons, yet in spite of its immense size it is merely a vast anteroom to the saloon.[34]

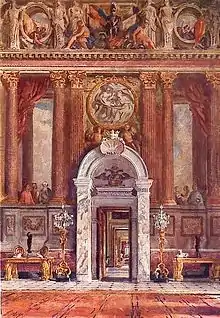

The saloon was also to have been painted by Thornhill, but the Duchess suspected him of overcharging, so the commission was given to Louis Laguerre. This room is an example of three-dimensional painting, or trompe l'œil, "trick-the-eye", a fashionable painting technique at the time. The Peace Treaty of Utrecht was about to be signed, so all the elements in the painting represent the coming of peace. The domed ceiling is an allegorical representation of Peace: John Churchill is in the chariot, he holds a zigzag thunderbolt of war, and the woman who holds back his arm represents Peace. The walls depict all the nations of the world who have come together peacefully. Laguerre also included a self-portrait placing himself next to Dean Jones, chaplain to the 1st Duke, another enemy of the Duchess, although she tolerated him in the household because he could play a good hand at cards. To the right of the doorway leading into the first stateroom, Laguerre included the French spies, said to have big ears and eyes because they may still be spying. Of the four marble door-cases in the room displaying the Duke's crest as a prince of the Holy Roman Empire, only one is by Gibbons, the other three were copied indistinguishably by the Duchess's cheaper craftsmen.[34]

The third remarkable room is the long library designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor in 1722–1725, (H), 183 ft (56 m) long, which was intended as a picture gallery. The ceiling has saucer domes, which were to have been painted by Thornhill, had the Duchess not upset him. The palace, and in particular this room, was furnished with the many valuable artefacts the Duke had been given, or sequestered as the spoils of war, including a fine art collection. Here in the library, rewriting history in her own indomitable style, the Duchess set up a larger than life statue of Queen Anne, its base recording their friendship.[34]

From the northern end of the library—in which is housed the largest pipe organ in private ownership in Europe, built by England's great organ builder Henry Willis & Sons—access is obtained to the raised colonnade which leads to the chapel (H). The chapel is perfectly balanced on the eastern side of the palace by the vaulted kitchen. This symmetrical balancing and equal weight given to both spiritual and physical nourishment would no doubt have appealed to Vanbrugh's renowned sense of humour, if not the Duchess'. The distance of the kitchen from even the private dining room ("O" on the plan) was obviously of no consideration, hot food being of less importance than to avoid having to inhale the odour of cooking and proximity of servants.[34]

Pipe organs

The Long Library organ was built in 1891 by the famous London firm of Henry Willis & Sons at a cost of £3,669.[35] It replaced a previous organ built in 1888 by Isaac Abbott of Leeds, which was removed to St Swithun's church, Hither Green.[36] Originally erected in the central bay, with its back to the water terraces, the Norwich firm of Norman & Beard moved it to the northwestern end of the library in 1902 and made a few tonal additions and, the following year, cleaned it.[35] No further changes were made until 1930, when the Willis firm lowered the pitch to modern concert pitch: a Welte automatic player was added in 1931, with 70 rolls cut by Marcel Dupré, Joseph Bonnet, Alfred Hollins, Edwin Lemare and Harry Goss-Custard also being supplied.[35] This remained in use for some time: the Duke of the time is said to have frequently sat at the organ bench and pretended to play the organ to his guests and they would applaud at the end. This practice is said to have been halted abruptly when the player started before the Duke had reached the organ. This famous instrument is regularly maintained and is played by visiting organists throughout the year, but its condition is declining: a fundraising campaign has been launched for its complete restoration.[37]

The organ in the chapel was built circa 1853 by Robert Postill of York:[38] it is notable as a rare unaltered example of this fine builder's work, speaking boldly and clearly into a generous acoustic.[38]

Park and gardens

%252C_pl._1_-_BL.jpg.webp)

Blenheim sits in the centre of a large undulating park, a classic example of the English landscape garden movement and style. When Vanbrugh first cast his eyes over it in 1704 he immediately conceived a typically grandiose plan: through the park trickled the small River Glyme, and Vanbrugh envisaged this marshy brook traversed by the "finest bridge in Europe". Thus, ignoring the second opinion offered by Sir Christopher Wren, the marsh was channelled into three small canal-like streams and across it rose a bridge of huge proportions, so huge it was reported to contain some 30-odd rooms. While the bridge was indeed an amazing wonder, in this setting it appeared incongruous, causing Alexander Pope to comment: "the minnows, as under this vast arch they pass, murmur, 'how like whales we look, thanks to your Grace.'"[39]

Horace Walpole saw it in 1760, shortly before Capability Brown's improvements: "the bridge, like the beggars at the old duchess's gate, begs for a drop of water and is refused."[40] Another of Vanbrugh's schemes was the great parterre, nearly half a mile long and as wide as the south front. Also in the park, completed after the 1st Duke's death, is the Column of Victory. It is 134 ft (41 m) high and terminates a great avenue of elms leading to the palace, which were planted in the positions of Marlborough's troops at the Battle of Blenheim. Vanbrugh had wanted an obelisk to mark the site of the former royal manor, and the trysts of Henry II which had taken place there, causing the 1st Duchess to remark, "If there were obelisks to bee made of all what our Kings have done of that sort, the countrey would bee stuffed with very odd things" (sic). The obelisk was never realised.[41]

.jpg.webp)

Following the 1st Duke's death the Duchess concentrated most of her considerable energies on the completion of the palace itself, and the park remained relatively unchanged until the arrival of Capability Brown in 1764. The 4th Duke employed Brown who immediately began an English landscape garden scheme to naturalise and enhance the landscape, with tree planting, and man-made undulations. However, the feature with which he is forever associated is the lake, a huge stretch of water created by damming the River Glyme and ornamented by a series of cascades where the river flows in and out. The lake was narrowed at the point of Vanbrugh's grand bridge, but the three small canal-like streams trickling underneath it were completely absorbed by one river-like stretch. Brown's great achievement at this point was to actually flood and submerge beneath the water level the lower stories and rooms of the bridge itself, thus reducing its incongruous height and achieving what is regarded by many as the epitome of an English landscape. Brown also grassed over the great parterre and the Great Court. The latter was re-paved by Duchêne in the early 20th century. The 5th Duke was responsible for several other garden follies and novelties.[42]

Sir William Chambers, assisted by John Yenn, was responsible for the small summerhouse known as "The Temple of Diana" down by the lake, where in 1908 Winston Churchill proposed to his future wife.[43]

The extensive landscaped park, woodlands and formal gardens of Blenheim are Grade I listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[44] Blenheim Park is a Site of Special Scientific Interest.[45]

Failing fortunes

...as we passed through the entrance archway and the lovely scenery burst upon me, Randolph said with pardonable pride: This is the finest view in England

Lady Randolph Churchill

On the death of the 1st Duke in 1722, as both his sons were dead, he was succeeded by his daughter Henrietta. This was an unusual succession and required a special Act of Parliament,[46] as only sons can usually succeed to an English dukedom. When Henrietta died, the title passed to Marlborough's grandson Charles Spencer, Earl of Sunderland, whose mother was Marlborough's second daughter Anne.[47]

The 1st Duke, as a soldier, was not a rich man and what fortune he possessed was mostly used for finishing the palace. In comparison with other British ducal families, the Marlboroughs were not very wealthy. Yet they existed quite comfortably until the time of the 5th Duke of Marlborough (1766–1840), a spendthrift who considerably depleted the family's remaining fortune. He was eventually forced to sell other family estates, but Blenheim was safe from him as it was entailed. This did not prevent him selling the Marlboroughs' Boccaccio for a mere £875 and his own library in over 4000 lots. On his death in 1840, his profligacy left the estate and family with financial problems.[48]

By the 1870s, the Marlboroughs were in severe financial trouble and in 1875 the 7th Duke sold the Marriage of Cupid and Psyche, together with the famed Marlborough gems, at auction for £10,000. However this was not enough to save the family. In 1880, the 7th Duke was forced to petition Parliament to break the protective entail on the Palace and its contents. This was achieved under the Blenheim Settled Estates Act 1880 and the door was now open for wholesale dispersal of Blenheim and its contents.[49][50][51] The first victim was the great Sunderland Library which was sold in 1882, including such volumes as The Epistles of Horace, printed at Caen in 1480, and the works of Josephus, printed at Verona in 1648. The 18,000 volumes raised almost £60,000. The sales continued to denude the palace: Raphael's Ansidei Madonna was sold for £70,000; Van Dyck's Equestrian Portrait of Charles I realised £17,500; and finally the "pièce de résistance" of the collection, Peter Paul Rubens' Rubens, His Wife Helena Fourment, and Their Son Peter Paul, and Their Son Frans (1633–1678), which had been given by the city of Brussels to the 1st Duke in 1704, was also sold, and is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.[52][53]

These sums of money, vast by the standards of the day, failed to cover the debts and the maintenance of the great palace remained beyond the Marlboroughs' resources. These had always been small in relation to their ducal rank and the size of their house. The British agricultural depression, which started in the 1870s, added to the family's problems. When the 9th Duke inherited in 1892, the land was generating dwindling income.[54]

9th Duke of Marlborough

Charles, 9th Duke of Marlborough (1871–1934) can be credited with saving both the palace and the family. Inheriting the near-bankrupt dukedom in 1892, he was forced to find a quick and drastic solution to the problems. Prevented by the strict social dictates of late 19th-century society from earning money, he was left with one solution: he had to marry into money. In November 1896 he coldly and openly without love married the American railroad heiress Consuelo Vanderbilt.[55][56]

The marriage was celebrated following lengthy negotiations with her divorced parents: her mother, Alva Vanderbilt, was desperate to see her daughter a duchess, and the bride's father, William Vanderbilt, paid for the privilege. The final price was $2,500,000 ($81.4 million today) in 50,000 shares of the capital stock of the Beech Creek Railway Company with a minimum 4% dividend guaranteed by the New York Central Railroad Company. The couple were given a further annual income each of $100,000 for life.[55][56]

The teenage Consuelo had been locked in her room by her mother until she agreed to the marriage. The marriage settlement was actually signed in the vestry of St. Thomas Episcopal Church, New York, immediately after the wedding vows had been made. In the carriage leaving the church, Marlborough told Consuelo he loved another woman, and would never return to America, as he "despised anything that was not British".[55][56]

The replenishing of Blenheim began on the honeymoon itself, with the replacement of the Marlborough gems. Tapestries, paintings and furniture were bought in Europe to fill the depleted palace. On their return the Duke began an exhaustive restoration and redecoration of the palace. The state rooms to the west of the saloon were redecorated with gilt boiseries in imitation of Versailles. Vanbrugh's subtle rivalry to Louis XIV's great palace was now completely undermined, as the interiors became mere pastiches of those of the greater palace.[32]

While this redecoration may not have been without fault (and the Duke later regretted it), other improvements were better received. Another problem caused by the redecoration was that the state and principal bedrooms were now moved upstairs, thus rendering the state rooms an enfilade of rather similar and meaningless drawing rooms. On the west terrace the French landscape architect Achille Duchêne was employed to create a water garden. On a second terrace below this were placed two great fountains in the style of Bernini, scaled models of those in the Piazza Navona which had been presented to the 1st Duke.[32]

Blenheim was once again a place of wonder and prestige. However, Consuelo was far from happy; she records many of her problems in her cynical and often less than candid biography The Glitter and the Gold. In 1906 she shocked society and left her husband. They divorced in 1921. She married a Frenchman, Jacques Balsan in 1921. She died in 1964, having lived to see her son become Duke of Marlborough. She frequently returned to Blenheim, the house she had hated and yet saved, albeit as the unwilling sacrifice.[32]

After his divorce the Duke married again, to a former friend of Consuelo, Gladys Deacon, another American. This eccentric lady was of an artistic disposition, and a painting of her eyes remains on the ceiling of the great north portico (see secondary lead image). A lower terrace was decorated with sphinxes modelled on Gladys and executed by W. Ward Willis in 1930. Before her marriage, while staying with the Marlboroughs, she caused a diplomatic incident by encouraging the young Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany to form an attachment.[32]

The prince had given her an heirloom ring, which the combined diplomatic services of two empires were charged to recover. After her marriage, Gladys was in the habit of dining with the Duke with a revolver by the side of her plate. Tiring of her, the Duke was temporarily forced to close Blenheim, and turn off the utilities to drive her out. They subsequently separated but did not divorce. The Duke died in 1934. His widow died in 1977.[32]

The 9th Duke was succeeded by his and Consuelo Vanderbilt's eldest son: John, 10th Duke of Marlborough (1897–1972), who after eleven years as a widower, remarried at the age of 74, to (Frances) Laura Charteris, formerly the wife of the 2nd Viscount Long and the 3rd Earl of Dudley, and granddaughter of the 11th Earl of Wemyss. The marriage was short-lived, however; the Duke died just six weeks later, on 11 March 1972. The bereaved Duchess complained of "the gloom and inhospitality of Blenheim" after his death, and soon moved out. In her autobiography, Laughter from a Cloud (1980), she referred to Blenheim Palace as "The Dump". She died in London in 1990.[32]

Second World War

During the war the 10th Duke welcomed the boys from Malvern College as evacuees. In September 1940 Security Service (MI5) was allowed to use the palace as its base until the end of the war.[57][58]

The palace today

The palace remains the home of the Dukes of Marlborough, the present incumbent of the title being Charles James (Jamie) Spencer-Churchill, 12th Duke of Marlborough. Charles James succeeded to the Dukedom upon his father's death on 16 October 2014.[59]

As of October 2016, the Marlboroughs still have to tender a copy of the French royal flag to the Monarch on the anniversary of the Battle of Blenheim as rent for the land that Blenheim Palace stands on.[60]

The palace, park, and gardens are open to the public on payment of an entry fee (maximum £32, as of September 2022).[61] Several tourist entertainment attractions separate from the palace are the Formal and Walled Gardens, Marlborough Maze and the Butterfly House. The palace is linked to the Walled Garden by a miniature railway, the Blenheim Park Railway.[62]

Lord Edward Spencer-Churchill, the brother of the current Duke, wished to feature a contemporary art programme within the historic setting of the palace where he spent his childhood. He founded Blenheim Art Foundation (BAF), a non-profit organisation, to present large-scale contemporary art exhibitions.[63] BAF launched on 1 October 2014 with the UK's largest ever exhibition by Ai Weiwei.[64] The foundation was conceived to give a vast number of people access to innovative contemporary artists working in the context of this historic palace.[65]

In September 2019, on the occasion of the opening of Maurizio Cattelan's show "Victory is not an option", the palace was the scene of a robbery: unknown thieves entered the palace at night time, just after the opening of the show, and stole a golden toilet, valued at $5 million, which had been installed by the artist in one of the bathrooms.[66]

The public have free access to about five miles (8 km) of public rights of way through the Great Park area of the grounds, which are accessible from Old Woodstock and from the Oxfordshire Way, and which are close to the Column of Victory.[67]

See also

- Blenheim Palace in film and media

- List of Baroque residences

- Noble Households – book with Blenheim Palace inventory of 1740

Footnotes

- "Blenheim". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- "Blenheim Palace". World Heritage sites. UNESCO. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- Voltaire wrote of Blenheim: "If only the apartments were as large as the walls are thick, this mansion would be convenient enough." Joseph Addison, Alexander Pope, and Robert Adam (normally an admirer of Vanbrugh's) also all criticised the design.

- Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 129

- Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, 10

- Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 92.

- Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 164

- Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 126

- Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, 240

- Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, 194

- Stephen, Leslie (1887). "Churchill, John (1650–1722)". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 10. pp. 315–341.

- "Writing table". The Royal Collection. The Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Field, p. 229, 251–5, 265, 344

- Pipe, Simon (23 October 2007). "Woodstock's lost royal palace". BBC Oxford. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- Masset, Claire (2 February 2015). "The imaginative genius of Sir John Vanbrugh, architect of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard". Discover Britain. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- When the Duchess came to build Marlborough House, her London home, in 1706, she employed Sir Christopher Wren. She later dismissed him too, because she felt that the contractors took advantage of him. She personally supervised the completion of the house. See Marlborough House Archived 26 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- Colvin, p. 850

- Seccombe, Thomas (1899). "Vanbrugh, John". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 58.

- Baggs, A. P.; Blair, W. J.; Chance, Eleanor; Colvin, Christina; Cooper, Janet; Day, C. J.; Selwyn, Nesta; Townley, S. C. (1990). "Blenheim: Blenheim Palace". In Crossley, Alan; Elrington, C. R. (eds.). A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 12, Wootton Hundred (South) Including Woodstock. British History Online. London. pp. 448–460. ISBN 978-0-19-722774-9. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Green, p. 39

- Green, p. 39

- "Inside Blenheim Palace, a dwelling fit for a duke". Globe and Mail. 28 September 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- The arms of the Duke of Marlborough with the statue of Britannia above Compare with figures on Tomb of Giuliano de Medici, New Sacristy, San Lorenzo, Florence (Category:Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici); figures above Moses and the Brazen Serpent, Sistine Chapel ceiling (File:Michelangelo Buonarroti 024.jpg); Monument of the Four Moors, of Ferdinando I de Medici, Leghorn by Pietro Tacco (File:Livorno, Monumento dei quattro mori a Ferdinando II (1626) - Foto Giovanni Dall'Orto, 13-4-2006 01.jpg); Coin of Marcus Aurelius, RIC III 1188, White Mountain Collection (File:Marcus Aurelius Dupondius 177 2020304.jpg)

- "Blenheim Palace 12342". Country Life Picture Gallery. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "Blenheim Palace". Patrick Baty. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Games, p. 334

- This clock tower, completed in 1710 at a cost of £1,435, was despised by the 1st Duchess, who referred to it as "A great thing where the Clock is, and which is Called a Tower of great Ornament (sic)".

- "Clock Tower, Blenheim Palace". Getty Images. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Mavor, p. 23

- Holmes: Marlborough: England's Fragile Genius, p. 477

- Historic England, "Blenheim Palace (1052912)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 16 October 2017

- Henrietta Spencer-Churchill

- Vanderbilt Balsan.

- "Blenheim Palace: Floorplans" (PDF). Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "The National Pipe Organ Register – Blenheim Palace: the Long Library". www.npor.org.uk.

- "The National Pipe Organ Register – Blenheim Palace: the Long Library, Abbott organ". www.npor.org.uk.

- "Blenheim Palace Organ Appeal". Archived from the original on 16 January 2013.

- "The National Pipe Organ Register – Blenheim Palace: Blenheim Palace Chapel". www.npor.org.uk.

- Bingham, p. 201

- Walpole to George Montagu, 19 July 1760. Walpole was not pleased with "Vanbrugh's quarries", with the inscriptions glorifying Marlborough "and all the old flock chairs, wainscot tables, and gowns and petticoats of queen Anne, that old Sarah could crowd among blocks of marble. It looks like the palace of an auctioneer, that has been chosen king of Poland."

- "Blenheim Part II Vision and egos". Record of a Baffled Spirit. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "Oxfordshire". Fabulous Follies. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "On the trail of Winston Churchill at Blenheim and beyond". The Telegraph. 23 January 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Historic England, "Blenheim Palace (1000434)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 16 October 2017

- "Designated Sites View: Blenheim Park". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- "2nd Duchess of Marlborough". Blenheimpalaceeducation.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1898). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 53. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Soames, Mary (1987). The Profligate Duke: George Spencer Churchill, Fifth Duke of Marlborough, and His Duchess. Harper-Collins. ISBN 978-0002163767.

- Purcell, p. 251

- Until the 1880s, the Law of Entail severely restricted the ability of an individual to sell inherited property, including books. The restriction could only be circumvented by resort to, expensive, private civil legislation, as was the Blenheim Settled Estates Act 1880. The Settled Land Act 1882 made the provisions contained in the Blenheim Act more easily and widely available.

- Klett, Jo; Hodgson, John. "Catalogue of the Sunderland Library". University of Manchester Library via Jisc. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- "Rubens, His Wife Helena Fourment (1614–1673), and Their Son Frans (1633–1678)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- "Rubens, His Wife Helena Fourment (1614–1673)". Metropolitan Museum. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- "Revised Management Plan" (PDF). Blenheim Palace. 2017. p. 26. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Tintner (2015), p. 144

- Cooper (2014), pp. 128–130

- "MI5 In World War II – MI5 – The Security Service". www.mi5.gov.uk.

- Andrew, Christopher (2009). The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5. Allen Lane. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-713-99885-6.

- Raynor, G. "Former drug addict and ex-convict Jamie Blandford becomes 12th Duke of Marlborough after father dies". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- "Interesting Facts About Blenheim Palace". #GetOutside. Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Tickets & Booking". The Blenheim Palace Heritage Foundation Charity. 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- "Visit and Explore". The Blenheim Palace Heritage Foundation Charity. 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Westall, Mark (23 July 2015). "Lawrence Weiner American artist and founding figure of Conceptual Art to be next artist at Blenheim Art Foundation". FAD Magazine. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- Kennedy, Maev (28 August 2014). "Ai Weiwei prepares for Blenheim Palace show but must keep his distance". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- "Lawrence Weiner. Within a Realm of Distance". 27 July 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- "$5 million solid gold toilet stolen in "surreal" Blenheim Palace heist". De Zeen. 16 September 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- See Ordnance Survey maps via map sources: 51.852°N 1.372°W

References

- Bingham, Jane (2015). The Cotswolds: A Cultural History. Signal Books. ISBN 978-1909930223.

- Colvin, Howard (2007). A biographical dictionary of British architects 1600–1840 (4th ed.). New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12508-5.

- Cooper, Dana (2014), Informal Ambassadors: American Women, Transatlantic Marriages, and Anglo-American Relations, 1865–1945., The Kent State University Press, ISBN 9781612778365 – via Project MUSE

- Cropplestone, Trewin (1963). World Architecture. London: Hamlyn.

- Dal Lago, Adalbert (1966). Ville Antiche. Milan: Fratelli Fabbri Editori.

- Downes, Kerry (1979). Hawksmoor. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Downes, Kerry (1987). Sir John Vanbrugh: A Biography. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 9780283994975.

- Field, Ophelia (2002). The Favourite: Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-76808-8.

- Games, Stephen (2014). Pevsner: The Complete Broadcast Talks: Architecture and Art on Radio and Television, 1945-1977. Routledge. ISBN 978-1409461975.

- Girouard, Mark (1978). Life in the English Country House. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300022735.

- Green, David Brontë (1982) [1950]. Blenheim Palace, Woodstock, Oxfordshire. Oxford: Alden Press.

- Halliday, F. E. (1967). An Illustrated Cultural History of England. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Harlin, Robert (1969). Historic Houses. London: Condé Nast Publications.

- Mavor, William Fordyce (2010) [1787]. Blenheim, a poem. Gale Ecco. ISBN 978-1170457344.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Sherwood, Jennifer (1974). The Buildings of England: Oxfordshire. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 459–475. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.

- Purcell, Mark (2019). The Country House Library. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-24868-5.

- Spencer-Churchill, The Lady Henrietta (2013). Blenheim and the Churchill Family – A personal portrait of one of the most important buildings in Europe. CICO Books. ISBN 978-1782490593.

- Tintner, Adeline R. (2015). Edith Wharton in Context: Essays on Intertextuality. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-5840-2.

- Turner, Roger (1999). Capability Brown and the Eighteenth century English Landscape (2nd ed.). Chichester: Phillimore.

- Vanderbilt, Arthur II (1989). Fortune's Children: The fall of the house of Vanderbilt. London: Michael Joseph.

- Vanderbilt Balsan, Consuelo (2012) [1953]. The Glitter and the Gold: The American Duchess-In Her Own Words. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1250017185.

- Watkin, David (1979). English Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson.

Further reading

- Conniff, Richard (February 2001). "The House that John Built". Smithsonian Journeys. Archived from the original on 2 October 2002.

- Cornforth, John (2004). Early Georgian Interiors. New Haven, Conn.; London: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, pp. 275–9 ISBN 978-0-30-010330-4 OCLC 938151474

- Murdoch, Tessa (ed.) (2006). Noble Households: Eighteenth-Century Inventories of Great English Houses. A Tribute to John Cornforth. Cambridge: John Adamson, pp. 273–83 ISBN 978-0-9524322-5-8 OCLC 78044620

- Wallechinsky, David; Wallace, Irving (1981). "Excesses of the Rich and Wealthy: The Vanderbilts". The People's Almanac.

External links

- Official website

- Churchill by Oswald Birley - UK Parliament Living Heritage

- Blenheim Art Foundation

- Blenheim Palace at Cotswolds Website

- "Blenheim Palace, Blenheim, Oxfordshire Gallery". Historic England Archive.

- "Blenheim Palace (Blenheim House) (Blenheim Castle) (Woodstock Manor)". The DiCamillo Companion.