Pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus Pinus (/ˈpiːnuːs/)[1] of the family Pinaceae. Pinus is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden accepts 187 species names of pines as current, together with more synonyms.[2] The American Conifer Society (ACS) and the Royal Horticultural Society accept 121 species. Pines are commonly found in the Northern Hemisphere. Pine may also refer to the lumber derived from pine trees; it is one of the more extensively used types of lumber. The pine family is the largest conifer family and there are currently 818 named cultivars (or trinomials) recognized by the ACS.[3]

| Pine Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Korean red pine (Pinus densiflora), North Korea | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Gymnosperms |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pinoideae |

| Genus: | Pinus L. |

| Type species | |

| Pinus sylvestris | |

| Subgenera | |

See List of Pinus species for complete taxonomy to species level. See list of pines by region for list of species by geographic distribution. | |

| |

| Range of Pinus | |

Description

Pine trees are evergreen, coniferous resinous trees (or, rarely, shrubs) growing 3–80 metres (10–260 feet) tall, with the majority of species reaching 15–45 m (50–150 ft) tall.[4] The smallest are Siberian dwarf pine and Potosi pinyon, and the tallest is an 81.8 m (268 ft) tall ponderosa pine located in southern Oregon's Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest.[4]

Pines are long lived and typically reach ages of 100–1,000 years, some even more. The longest-lived is the Great Basin bristlecone pine (P. longaeva). One individual of this species, dubbed "Methuselah", is one of the world's oldest living organisms at around 4,800 years old. This tree can be found in the White Mountains of California.[5] An older tree, now cut down, was dated at 4,900 years old.[6][7] It was discovered in a grove beneath Wheeler Peak and it is now known as "Prometheus" after the Greek immortal.[7]

The spiral growth of branches, needles, and cones scales may be arranged in Fibonacci number ratios.[8][9] The new spring shoots are sometimes called "candles"; they are covered in brown or whitish bud scales and point upward at first, then later turn green and spread outward. These "candles" offer foresters a means to evaluate fertility of the soil and vigour of the trees.

Roots of an old pine in Ystad (2020)

Roots of an old pine in Ystad (2020) Ancient Pinus longaeva, California, US

Ancient Pinus longaeva, California, US A large eastern white pine (P. strobus) in Southern Ontario, Canada

A large eastern white pine (P. strobus) in Southern Ontario, Canada A Khasi pine in Benguet, Philippines

A Khasi pine in Benguet, Philippines Crooked Forest in Nowe Czarnowo, Poland

Crooked Forest in Nowe Czarnowo, Poland Pine forest in Vagamon, southern Western Ghats, Kerala (India)

Pine forest in Vagamon, southern Western Ghats, Kerala (India) Huangshan pine (Pinus hwangshanensis), Anhui, China

Huangshan pine (Pinus hwangshanensis), Anhui, China Illustration of needles, cones, and seeds of Scots pine (P. sylvestris)

Illustration of needles, cones, and seeds of Scots pine (P. sylvestris) Flowering young pine cones

Flowering young pine cones A growing female cone of a Scots pine on a mountain in Perry County, Pennsylvania

A growing female cone of a Scots pine on a mountain in Perry County, Pennsylvania.jpg.webp) A fully grown and freshly fallen female pine cone (P. strobus)

A fully grown and freshly fallen female pine cone (P. strobus) Seeds of the Korean pine (P. koraiensis)

Seeds of the Korean pine (P. koraiensis) A controlled burn in a European black pine (P. nigra) woodland, Portugal

A controlled burn in a European black pine (P. nigra) woodland, Portugal

Bark

The bark of most pines is thick and scaly, but some species have thin, flaky bark.[10] The branches are produced in regular "pseudo whorls", actually a very tight spiral but appearing like a ring of branches arising from the same point. Many pines are uninodal, producing just one such whorl of branches each year, from buds at the tip of the year's new shoot, but others are multinodal, producing two or more whorls of branches per year.

Foliage

Pines have four types of leaf:

- Seed leaves (cotyledons) on seedlings are borne in a whorl of 4–24.

- Juvenile leaves, which follow immediately on seedlings and young plants, are 2–6 centimetres (3⁄4–2+1⁄4 inches) long, single, green or often blue-green, and arranged spirally on the shoot. These are produced for six months to five years, rarely longer.

- Scale leaves, similar to bud scales, are small, brown and not photosynthetic, and arranged spirally like the juvenile leaves.

- Needles, the adult leaves, are green (photosynthetic) and bundled in clusters called fascicles. The needles can number from one to seven per fascicle, but generally number from two to five. Each fascicle is produced from a small bud on a dwarf shoot in the axil of a scale leaf. These bud scales often remain on the fascicle as a basal sheath. The needles persist for 1.5–40 years, depending on species. If a shoot's growing tip is damaged (e.g. eaten by an animal), the needle fascicles just below the damage will generate a stem-producing bud, which can then replace the lost growth tip.

Cones

Pines are monoecious, having the male and female cones on the same tree.[11]: 205 The male cones are small, typically 1–5 cm long, and only present for a short period (usually in spring, though autumn in a few pines), falling as soon as they have shed their pollen. The female cones take 1.5–3 years (depending on species) to mature after pollination, with actual fertilization delayed one year. At maturity the female cones are 3–60 cm long. Each cone has numerous spirally arranged scales, with two seeds on each fertile scale; the scales at the base and tip of the cone are small and sterile, without seeds.

The seeds are mostly small and winged, and are anemophilous (wind-dispersed), but some are larger and have only a vestigial wing, and are bird-dispersed. Female cones are woody and sometimes armed to protect developing seeds from foragers. At maturity, the cones usually open to release the seeds. In some of the bird-dispersed species, for example whitebark pine,[12] the seeds are only released by the bird breaking the cones open. In others, the seeds are stored in closed cones for many years until an environmental cue triggers the cones to open, releasing the seeds. This is called serotiny. The most common form of serotiny is pyriscence, in which a resin binds the cones shut until melted by a forest fire, for example in P. rigida.

Taxonomy

Pines are gymnosperms. The genus is divided into two subgenera based on the number of fibrovascular bundles in the needle. The subgenera can be distinguished by cone, seed, and leaf characters:

- Pinus subg. Pinus, the yellow, or hard pine group, generally with harder wood and two or three needles per fascicle.[13] The subgenus is also named diploxylon, on account of its two fibrovascular bundles.

- Pinus subg. Strobus, the white, or soft pine group. Its members usually have softer wood and five needles per fascicle.[13] The subgenus is also named haploxylon, on account of its one fibrovascular bundle.

Phylogenetic evidence indicates that both subgenera have a very ancient divergence from one another, having diverged during the late Jurassic.[14] Each subgenus is further divided into sections and subsections.

Many of the smaller groups of Pinus are composed of closely related species with recent divergence and history of hybridization. This results in low morphological and genetic differences. This, coupled with low sampling and underdeveloped genetic techniques, has made taxonomy difficult to determine.[15] Recent research using large genetic datasets has clarified these relationships into the groupings we recognize today.

Etymology

The modern English name "pine" derives from Latin pinus, which some have traced to the Indo-European base *pīt- ‘resin’ (source of English pituitary).[16] Before the 19th century, pines were often referred to as firs (from Old Norse fura, by way of Middle English firre). In some European languages, Germanic cognates of the Old Norse name are still in use for pines — in Danish fyr, in Norwegian fura/fure/furu, Swedish fura/furu, Dutch vuren, and German Föhre — but in modern English, fir is now restricted to fir (Abies) and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga).

Phylogeny

Pinus is the largest genus of the Pinaceae, the pine family, which first appeared in the Jurassic period.[17] Based on recent Transcriptome analysis, Pinus is most closely related to the genus Cathaya, which in turn is closely related to spruces. These genera, with firs and larches, form the pinoid clade of the Pinaceae.[18] Pines first appeared during the Early Cretaceous, with the oldest verified fossil of the genus is Pinus yorkshirensis from the Hauterivian-Barremian boundary (131–129 million years ago) from the Speeton Clay, England.[19]

The evolutionary history of the genus Pinus has been complicated by hybridization. Pines are prone to inter-specific breeding. Wind pollination, long life spans, overlapping generations, large population size, and weak reproductive isolation make breeding across species more likely.[20] As the pines have diversified, gene transfer between different species has created a complex history of genetic relatedness.

The following cladogram shows the phylogenetic relationships between the pine species as described in 2021.[21]

| Pinus |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Distribution and habitat

Pines are native to the Northern Hemisphere, and to a few parts from the tropics to temperate regions in the Southern Hemisphere. Most regions of the Northern Hemisphere host some native species of pines. One species (Sumatran pine) crosses the equator in Sumatra to 2°S. In North America, various species occur in regions at latitudes from as far north as 66°N to as far south as 12°N.

Pines may be found in a very large variety of environments, ranging from semi-arid desert to rainforests, from sea level up to 5,200 m (17,100 ft), from the coldest to the hottest environments on Earth. They often occur in mountainous areas with favorable soils and at least some water.[22]

Various species have been introduced to temperate and subtropical regions of both hemispheres, where they are grown as timber or cultivated as ornamental plants in parks and gardens. A number of such introduced species have become naturalized, and some species are considered invasive in some areas[23] and threaten native ecosystems.

Ecology

Pines grow well in acid soils, some also on calcareous soils; most require good soil drainage, preferring sandy soils, but a few (e.g. lodgepole pine) can tolerate poorly drained wet soils. A few are able to sprout after forest fires (e.g. Canary Island pine). Some species of pines (e.g. bishop pine) need fire to regenerate, and their populations slowly decline under fire suppression regimens.

Pine trees are beneficial to the environment since they can remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Although several studies have indicated that after the establishment of pine plantations in grasslands, there is an alteration of carbon pools including a decrease of the soil organic carbon pool.[24]

Several species are adapted to extreme conditions imposed by elevation and latitude (e.g. Siberian dwarf pine, mountain pine, whitebark pine, and the bristlecone pines). The pinyon pines and a number of others, notably Turkish pine and gray pine, are particularly well adapted to growth in hot, dry semidesert climates.[25]

Pine pollen may play an important role in the functioning of detrital food webs.[26] Nutrients from pollen aid detritivores in development, growth, and maturation, and may enable fungi to decompose nutritionally scarce litter.[26] Pine pollen is also involved in moving plant matter between terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.[26]

Wildlife

Pine needles serve as food for various Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) species. Several species of pine are attacked by nematodes, causing pine wilt disease, which can kill some quickly. Some of these Lepidoptera species, many of them moths, specialize in feeding on only one or sometimes several species of pine. Beside that many species of birds and mammals shelter in pine habitat or feed on pine nuts.

The seeds are commonly eaten by birds, such as grouse, crossbills, jays, nuthatches, siskins, and woodpeckers, and by squirrels. Some birds, notably the spotted nutcracker, Clark's nutcracker, and pinyon jay, are of importance in distributing pine seeds to new areas. Pine needles are sometimes eaten by the Symphytan species pine sawfly, and goats.[27]

Uses

.jpg.webp) A picture portraying the turpentine industry

A picture portraying the turpentine industry Forchem tall oil refinery in Rauma, Finland

Forchem tall oil refinery in Rauma, Finland Pine needle baskets

Pine needle baskets Logging Pinus ponderosa, Arizona, US

Logging Pinus ponderosa, Arizona, US Pinus sylvestris prepared for transport, Hungary

Pinus sylvestris prepared for transport, Hungary Tongue and groove flooring of solid German pine

Tongue and groove flooring of solid German pine Chinese ink stick

Chinese ink stick

Lumber and construction

Pines are among the most commercially important tree species valued for their timber and wood pulp throughout the world.[28][29] In temperate and tropical regions, they are fast-growing softwoods that grow in relatively dense stands, their acidic decaying needles inhibiting the sprouting of competing hardwoods. Commercial pines are grown in plantations for timber that is denser and therefore more durable than spruce (Picea). Pine wood is widely used in high-value carpentry items such as furniture, window frames, panelling, floors, and roofing, and the resin of some species is an important source of turpentine.

Because pine wood has no insect- or decay-resistant qualities after logging, in its untreated state it is generally recommended for indoor construction purposes only (indoor drywall framing, for example). For outside use, pine needs to be treated with copper azole, chromated copper arsenate or other suitable chemical preservative.[30]

Ornamental uses

Many pine species make attractive ornamental plantings for parks and larger gardens with a variety of dwarf cultivars being suitable for smaller spaces. Pines are also commercially grown and harvested for Christmas trees. Pine cones, the largest and most durable of all conifer cones, are craft favorites. Pine boughs, appreciated especially in wintertime for their pleasant smell and greenery, are popularly cut for decorations.[31] Pine needles are also used for making decorative articles such as baskets, trays, pots, etc., and during the U.S. Civil War, the needles of the longleaf pine "Georgia pine" were widely employed in this.[32] This originally Native American skill is now being replicated across the world. Pine needle handicrafts are made in the US, Canada, Mexico, Nicaragua, and India. Pine needles are also versatile and have been used by Latvian designer Tamara Orjola to create different biodegradable products including paper, furniture, textiles and dye.[33]

Farming

When grown for sawing timber, pine plantations can be harvested after 25 years, with some stands being allowed to grow up to 50 (as the wood value increases more quickly as the trees age). Imperfect trees (such as those with bent trunks or forks, smaller trees, or diseased trees) are removed in a "thinning" operation every 5–10 years. Thinning allows the best trees to grow much faster, because it prevents weaker trees from competing for sunlight, water, and nutrients. Young trees removed during thinning are used for pulpwood or are left in the forest, while most older ones are good enough for saw timber.[34]

A 30-year-old commercial pine tree grown in good conditions in Arkansas will be about 0.3 m (1 ft) in diameter and about 20 m (66 ft) high. After 50 years, the same tree will be about 0.5 m (1+1⁄2 ft) in diameter and 25 m (82 ft) high, and its wood will be worth about seven times as much as the 30-year-old tree. This however depends on the region, species and silvicultural techniques. In New Zealand, a plantation's maximum value is reached after around 28 years with height being as high as 30 m (98 ft) and diameter 0.5 m (1+1⁄2 ft), with maximum wood production after around 35 years (again depending on factors such as site, stocking and genetics). Trees are normally planted 3–4 m apart, or about 1,000 per hectare (100,000 per square kilometre).[35][36][37][38]

Food and nutrients

The seeds (pine nuts) are generally edible; the young male cones can be cooked and eaten, as can the bark of young twigs.[39] Some species have large pine nuts, which are harvested and sold for cooking and baking. They are an essential ingredient of pesto alla genovese.

The soft, moist, white inner bark (cambium) beneath the woody outer bark is edible and very high in vitamins A and C.[3] It can be eaten raw in slices as a snack or dried and ground up into a powder for use as an ersatz flour or thickener in stews, soups, and other foods, such as bark bread.[40] Adirondack Indians got their name from the Mohawk Indian word atirú:taks, meaning "tree eaters".[40]

A tea is made by steeping young, green pine needles in boiling water (known as tallstrunt in Sweden).[40] In eastern Asia, pine and other conifers are accepted among consumers as a beverage product, and used in teas, as well as wine.[41] In Greece, the wine retsina is flavoured with Aleppo pine resin.

Pine needles from Pinus densiflora were found to contain 30.54 milligram/gram of proanthocyanidins when extracted with hot water.[42] Comparative to ethanol extraction resulting in 30.11 mg/g, simply extracting in hot water is preferable.

In traditional Chinese medicine, pine resin is used for burns, wounds and dermal complaints.[43]

Culture

Pines have been a frequently mentioned tree throughout history, including in literature, paintings and other art, and in religious texts.

Literature

Writers of various nationalities and ethnicities have written of pines. Among them, John Muir,[44] Dora Sigerson Shorter,[45] Eugene Field,[46] Bai Juyi,[47] Theodore Winthrop,[48] and Rev. George Allan D.D.[49]

Art

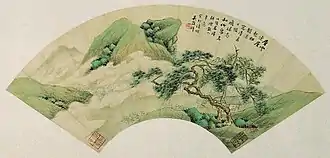

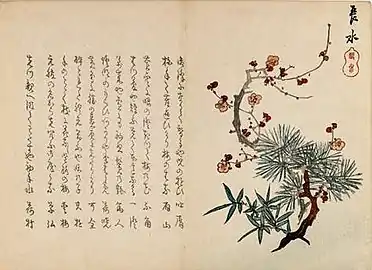

Chosui Yabu's inscribed woodcut of Three Auspicious Friends (The Three Friends of Winter) in the Brooklyn Museum (c. 1860)

Chosui Yabu's inscribed woodcut of Three Auspicious Friends (The Three Friends of Winter) in the Brooklyn Museum (c. 1860)_(16982300531).jpg.webp) Under the Pines, Evening, Claude Monet (1888) (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

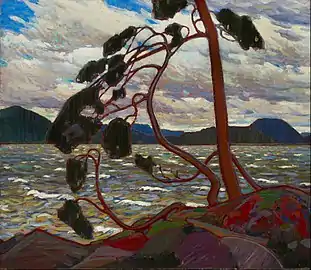

Under the Pines, Evening, Claude Monet (1888) (Philadelphia Museum of Art) The West Wind (1917), Canadian painter Tom Thomson's iconic portrait of red pines in Algonquin Park, Ontario

The West Wind (1917), Canadian painter Tom Thomson's iconic portrait of red pines in Algonquin Park, Ontario

Pines are often featured in art, whether painting and fine art,[50] drawing,[51] photography, or folk art.

Religious texts

Pine trees, as well as other conifers, are mentioned in some verses of the Bible, depending on the translation. In the Book of Nehemiah 8:15, the King James Version gives the following translation:[52]

"And that they should publish and proclaim in all their cities, and in Jerusalem, saying, Go forth unto the mount, and fetch olive branches, and pine branches [emphasis added], and myrtle branches, and palm branches, and branches of thick trees, to make booths, as it is written."

However, the term here in Hebrew (עץ שמן) means "oil tree" and it is not clear what kind of tree is meant. Pines are also mentioned in some translations of Isaiah 60:13, such as the King James:

"The glory of Lebanon shall come unto thee, the fir tree, the pine tree, and the box together, to beautify the place of my sanctuary; and I will make the place of my feet glorious."

Again, it is not clear what tree is meant (תדהר in Hebrew), and other translations use "pine" for the word translated as "box" by the King James (תאשור in Hebrew).

Some botanical authorities believe that the Hebrew word "ברוש" (bərōsh), which is used many times in the Bible, designates P. halepensis, or in Hosea 14:8[53] which refers to fruit, Pinus pinea, the stone pine. [54] The word used in modern Hebrew for pine is "אֹ֖רֶן" (oren), which occurs only in Isaiah 44:14,[55] but two manuscripts have "ארז" (cedar), a much more common word.[56]

Chinese culture

The pine is a motif in Chinese art and literature, which sometimes combines painting and poetry in the same work. Some of the main symbolic attributes of pines in Chinese art and literature are longevity and steadfastness: the pine retains its green needles through all the seasons. Sometimes the pine and cypress are paired. At other times the pine, plum, and bamboo are considered as the "Three Friends of Winter".[57] Many Chinese art works and/or literature (some involving pines) have been done using paper, brush, and Chinese ink: interestingly enough, one of the main ingredients for Chinese ink has been pine soot.

See also

- El Pino (The Pine Tree)

- Pine barrens

- Pine-cypress forest

- Pine Tree Flag

- Tree of Peace

References

- Sunset Western Garden Book. 1995. pp. 606–607. ISBN 978-0-376-03851-7.

- "Pinus (L.)". World Flora Online. The World Flora Online Consortium. 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- "Pinus / pine | Conifer Genus". American Conifer Society. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Fattig P (23 January 2011). "Tallest of the tall". Mail Tribune. Medford, Oregon. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Ryan M, Richardson DM (December 1999). "The Complete Pine". BioScience. 49 (12): 1023–1024. doi:10.2307/1313736. JSTOR 1313736.

- Miranda, Carolina A. (28 February 2015). "Follow-up: More tales of the Prometheus tree and how it died". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Eveleth, Rose (15 November 2012). "How One Man Accidentally Killed the Oldest Tree Ever". Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Zeng, Lanling; Wang, Guozhao (2009). "Modeling golden section in plants". Progress in Natural Science. 19 (2): 255–260. doi:10.1016/j.pnsc.2008.07.004.

The ratio between two pine needles is 0.618 [...] the angle between the two neighbors is about 135° and the angle between the main stem and each branch is close to 34.4° which is the golden section of 90°

- Bracewell, Ronald; Rawlings, John. "Pinus (Pine) Notes". Trees of Stanford. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- V.I. Porter. (2018). Mystique Melodies. Dorrance Publishing.

- Judd, WS; Campbell, CS; Kellogg, EA; Stevens, PF; Donoghue, MJ (2002). Plant systematics, a phylogenetic approach (2 ed.). Sinauer Associates, Sunderland MA, USA. ISBN 0-87893-403-0.

- Tomback DF (June 1982). "Dispersal of Whitebark Pine seeds by Clark's Nutcracker: a mutualism hypothesis". The Journal of Animal Ecology. 51 (2): 451–467. doi:10.2307/3976. JSTOR 3976.

- Burton Verne Barnes; Warren Herbert Wagner (January 2004). Michigan Trees: A Guide to the Trees of the Great Lakes Region. University of Michigan Press. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-0-472-08921-5. Archived from the original on 2016-05-11.

- Stull, Gregory W.; Qu, Xiao-Jian; Parins-Fukuchi, Caroline; Yang, Ying-Ying; Yang, Jun-Bo; Yang, Zhi-Yun; Hu, Yi; Ma, Hong; Soltis, Pamela S.; Soltis, Douglas E.; Li, De-Zhu (July 19, 2021). "Gene duplications and phylogenomic conflict underlie major pulses of phenotypic evolution in gymnosperms". Nature Plants. 7 (8): 1015–1025. doi:10.1038/s41477-021-00964-4. ISSN 2055-0278. PMID 34282286. S2CID 236141481.

- Flores-Rentería L, Wegier A, Ortega Del Vecchyo D, Ortíz-Medrano A, Piñero D, Whipple AV, et al. (December 2013). "Genetic, morphological, geographical and ecological approaches reveal phylogenetic relationships in complex groups, an example of recently diverged pinyon pine species (Subsection Cembroides)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 69 (3): 940–9. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2013.06.010. PMID 23831459.

- "Where Are You From? - Credo Reference". credoreference.com.

- Ran JH, Shen TT, Wu H, Gong X, Wang XQ (December 2018). "Phylogeny and evolutionary history of Pinaceae updated by transcriptomic analysis". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 129: 106–116. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2018.08.011. PMID 30153503. S2CID 52110440.

- Stull, Gregory W.; Qu, Xiao-Jian; Parins-Fukuchi, Caroline; Yang, Ying-Ying; Yang, Jun-Bo; Yang, Zhi-Yun; Hu, Yi; Ma, Hong; Soltis, Pamela S.; Soltis, Douglas E.; Li, De-Zhu (July 19, 2021). "Gene duplications and phylogenomic conflict underlie major pulses of phenotypic evolution in gymnosperms". Nature Plants. 7 (8): 1015–1025. doi:10.1038/s41477-021-00964-4. ISSN 2055-0278. PMID 34282286. S2CID 236141481.

- Patricia E. Ryberg; Gar W. Rothwell; Ruth A. Stockey; Jason Hilton; Gene Mapes; James B. Riding (2012). "Reconsidering Relationships among Stem and Crown Group Pinaceae: Oldest Record of the Genus Pinus from the Early Cretaceous of Yorkshire, United Kingdom". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 173 (8): 917–932. doi:10.1086/667228. S2CID 85402168.

- Hernández-León S, Gernandt DS, Pérez de la Rosa JA, Jardón-Barbolla L (2013-07-30). "Phylogenetic relationships and species delimitation in pinus section trifoliae inferrred from plastid DNA". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e70501. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...870501H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070501. PMC 3728320. PMID 23936218.

- Jin WT, Gernandt DS, Wehenkel C, Xia XM, Wei XX, Wang XQ (May 2021), "Phylogenomic and ecological analyses reveal the spatiotemporal evolution of global pines", PNAS, 118 (20): e2022302118, Bibcode:2021PNAS..11822302J, doi:10.1073/pnas.2022302118, PMC 8157994, PMID 33941644

- "Pine Trees". Basic Biology. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- "Pinus ssp. (tree), General Impact". Global Invasive Species Database. Invasive Species Specialist Group. 13 March 2006. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- Weber, M. (2021). Impacts of pine plantations on carbon stocks of páramo sites in southern Ecuador. Carbon Balance and Management., 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13021-021-00168-5

- "Pinus sabiniana Dougl". www.srs.fs.usda.gov. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- Filipiak M (2016-01-01). "Pollen Stoichiometry May Influence Detrital Terrestrial and Aquatic Food Webs". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4: 138. doi:10.3389/fevo.2016.00138.

- "Pine Sawflies". Penn State Extension. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- "Choosing a Timber Species - Timber Frame HQ". Timber Frame HQ. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- "Trees for pulp" (PDF). Paper.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-18. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- "Timber treatment". weathertight.org.nz. 2010-10-18. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- "5 Ways to Decorate with Pine Boughs". Home Decorating Trends - Homedit. 2012-12-04. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- McAfee MJ (1911). The pine-needle basket book. The Library of Congress. New York : Pine-Needle Pub. Co.

- Solanki S (2018-12-17). "5 radical material innovations that will shape tomorrow". CNN Style. Retrieved 2018-12-17.

- "The Pine Plantation Rotation" (PDF). Forests NSW. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-08. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Frank A. Roth II, Extension Forester. "Thinning to improve pine timber" (PDF). University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "NZ Farm Forestry - Radiata pine silviculture in Chile". www.nzffa.org.nz. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- "NZ Farm Forestry - NZFFA guide sheet No. 1: An Introduction to Growing Radiata Pine". www.nzffa.org.nz. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- Manley, Bruce (2020-07-01). "Impact on profitability, risk, optimum rotation age and afforestation of changing the New Zealand emissions trading scheme to an averaging approach". Forest Policy and Economics. 116: 102205. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102205. ISSN 1389-9341. S2CID 219518345.

- The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants. United States Department of the Army. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. 2009. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-60239-692-0. OCLC 277203364.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Angier, Bradford (1974). Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books. pp. 166–167. ISBN 0-8117-0616-8. OCLC 799792.

- Zeng WC, Jia LR, Zhang Y, Cen JQ, Chen X, Gao H, Feng S, Huang YN (March 2011). "Antibrowning and antimicrobial activities of the water-soluble extract from pine needles of Cedrus deodara". Journal of Food Science. 76 (2): C318–23. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.02023.x. PMID 21535752.

- Park YS, Jeon MH, Hwang HJ, Park MR, Lee SH, Kim SG, Kim M (August 2011). "Antioxidant activity and analysis of proanthocyanidins from pine (Pinus densiflora) needles". Nutrition Research and Practice. 5 (4): 281–7. doi:10.4162/nrp.2011.5.4.281. PMC 3180677. PMID 21994521.

- Ulukanli Z, Karabörklü S, Bozok F, Ates B, Erdogan S, Cenet M, Karaaslan MG (December 2014). "Chemical composition, antimicrobial, insecticidal, phytotoxic and antioxidant activities of Mediterranean Pinus brutia and Pinus pinea resin essential oils". Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines. 12 (12): 901–10. doi:10.1016/s1875-5364(14)60133-3. PMID 25556061.

- Muir J. The Yosemite.

- Shorter DS. The Secret.

- Field, Eugene. Poems of Childhood/Norse Lullaby.

- Bai Juyi "The Pine Trees in the Courtyard"

- Winthrop T. Life in the Open Air.

- The Book of Scottish Song.

- Pissarro C (1903). "Work by Camille Pissarro". Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Britton NL, Brown A (1913). "Pinus strobus L". Illustrated flora of the northern states and Canada. Vol. 1. USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- "NEHEMIAH 8:15 KJV". www.kingjamesbibleonline.org. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- "Hosea 14:8".

- Wycliffe Bible Dictionary. entry Plants: Fir: Hendrickson Publishers. 1975.

- "Isaiah 44:14".

- Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia ad loc.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (2003 [1986 (German version 1983)]), A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00228-1, sub "Pine".

Bibliography

- Farjon A (2005). Pines (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-13916-8.

- Little Jr EL, Critchfield WB (1969). Subdivisions of the Genus Pinus (Pines). Misc. Publ. 1144 (Superintendent of Documents Number: A 1.38:1144) (Report). US Department of Agriculture.

- Richardson DM, ed. (1998). Ecology and Biogeography of Pinus. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 530. ISBN 0-521-55176-5.

- Sulavik SB (2007). Adirondack; Of Indians and Mountains, 1535-1838. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press. pp. 244 pages. ISBN 978-1-930098-79-4.

- Mirov NT (1967). The Genus Pinus. New York, NY: Ronald Press.

- "Classification of pines". The Lovett Pinetum Charitable Foundation.

- Mirov NT, Stanley RG (1959). "The Pine Tree". Annual Review of Plant Physiology. 10: 223–238. doi:10.1146/annurev.pp.10.060159.001255.

- Philips R (1979). Trees of North America and Europe. New York, NY: Random House, Inc. ISBN 0-394-50259-0.

- Earle, Christopher J., ed. (2018). "Pinus". The Gymnosperm Database.

External links

- 40 Species of Pine Trees You Can Grow by The Spruce

- Jepson eFlora, The Jepson Herbarium, University of California, Berkeley, covers Californian species

- Pinus in Flora of North America

- Pinus in the USDA Plants Database