Planetarium

A planetarium (pl. planetariums or planetaria) is a theatre built primarily for presenting educational and entertaining shows about astronomy and the night sky, or for training in celestial navigation.[1][2][3]

(Belgrade Planetarium, Serbia)

(Belgrade Planetarium, Serbia)

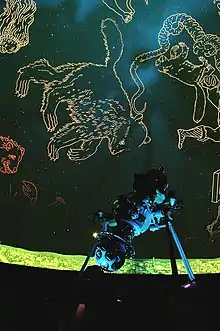

A dominant feature of most planetariums plis the large dome-shaped projection screen onto which scenes of stars, planets, and other celestial objects can be made to appear and move realistically to simulate their motion. The projection can be created in various ways, such as a star ball, slide projector, video, fulldome projector systems, and lasers. Typical systems can be set to simulate the sky at any point in time, past or present, and often to depict the night sky as it would appear from any point of latitude on Earth.

Planetaria range in size from the 37 meter dome in St. Petersburg, Russia (called “Planetarium No 1”) to three-meter inflatable portable domes where attendees sit on the floor. The largest planetarium in the Western Hemisphere is the Jennifer Chalsty Planetarium at Liberty Science Center in New Jersey, its dome measuring 27 meters in diameter. The Birla Planetarium in Kolkata, India is the largest by seating capacity, having 630 seats.[4] In North America, the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City has the greatest number of seats, at 423.

The term planetarium is sometimes used generically to describe other devices which illustrate the Solar System, such as a computer simulation or an orrery. Planetarium software refers to a software application that renders a three-dimensional image of the sky onto a two-dimensional computer screen, or in a virtual reality headset for a 3D representation.[5] The term planetarian is used to describe a member of the professional staff of a planetarium.

History

Early

The ancient Greek polymath Archimedes is attributed with creating a primitive planetarium device that could predict the movements of the Sun and the Moon and the planets. The discovery of the Antikythera mechanism proved that such devices already existed during antiquity, though likely after Archimedes' lifetime. Campanus of Novara described a planetary equatorium in his Theorica Planetarum, and included instructions on how to build one. The Globe of Gottorf built around 1650 had constellations painted on the inside.[6] These devices would today usually be referred to as orreries (named for the Earl of Orrery). In fact, many planetariums today have projection orreries, which project onto the dome the Solar System (including the Sun and planets up to Saturn) in their regular orbital paths.

In 1229, following the conclusion of the Fifth Crusade, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen brought back a tent with scattered holes representing stars or planets. The device was operated internally with a spinnable table that rotated the tent.[7]

The small size of typical 18th century orreries limited their impact, and towards the end of that century a number of educators attempted to create a larger sized version. The efforts of Adam Walker (1730–1821) and his sons are noteworthy in their attempts to fuse theatrical illusions with education. Walker's Eidouranion was the heart of his public lectures or theatrical presentations. Walker's son describes this "Elaborate Machine" as "twenty feet high, and twenty-seven in diameter: it stands vertically before the spectators, and its globes are so large, that they are distinctly seen in the most distant parts of the Theatre. Every Planet and Satellite seems suspended in space, without any support; performing their annual and diurnal revolutions without any apparent cause". Other lecturers promoted their own devices: R E Lloyd advertised his Dioastrodoxon, or Grand Transparent Orrery, and by 1825 William Kitchener was offering his Ouranologia, which was 42 feet (13 m) in diameter. These devices most probably sacrificed astronomical accuracy for crowd-pleasing spectacle and sensational and awe-provoking imagery.

The oldest, still working planetarium can be found in the Dutch town Franeker. It was built by Eise Eisinga (1744–1828) in the living room of his house. It took Eisinga seven years to build his planetarium, which was completed in 1781.[8]

In 1905 Oskar von Miller (1855–1934) of the Deutsches Museum in Munich commissioned updated versions of a geared orrery and planetarium from M Sendtner, and later worked with Franz Meyer, chief engineer at the Carl Zeiss optical works in Jena, on the largest mechanical planetarium ever constructed, capable of displaying both heliocentric and geocentric motion. This was displayed at the Deutsches Museum in 1924, construction work having been interrupted by the war. The planets travelled along overhead rails, powered by electric motors: the orbit of Saturn was 11.25 m in diameter. 180 stars were projected onto the wall by electric bulbs.

While this was being constructed, von Miller was also working at the Zeiss factory with German astronomer Max Wolf, director of the Landessternwarte Heidelberg-Königstuhl observatory of the University of Heidelberg, on a new and novel design, inspired by Wallace W. Atwood's work at the Chicago Academy of Sciences and by the ideas of Walther Bauersfeld and Rudolf Straubel[9] at Zeiss. The result was a planetarium design which would generate all the necessary movements of the stars and planets inside the optical projector, and would be mounted centrally in a room, projecting images onto the white surface of a hemisphere. In August 1923, the first (Model I) Zeiss planetarium projected images of the night sky onto the white plaster lining of a 16 m hemispherical concrete dome, erected on the roof of the Zeiss works. The first official public showing was at the Deutsches Museum in Munich on October 21, 1923.[10]

After World War II

When Germany was divided into East and West Germany after the war, the Zeiss firm was also split. Part remained in its traditional headquarters at Jena, in East Germany, and part migrated to West Germany. The designer of the first planetariums for Zeiss, Walther Bauersfeld, also migrated to West Germany with the other members of the Zeiss management team. There he remained on the Zeiss West management team until his death in 1959.

The West German firm resumed making large planetariums in 1954, and the East German firm started making small planetariums a few years later. Meanwhile, the lack of planetarium manufacturers had led to several attempts at construction of unique models, such as one built by the California Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, which operated 1952–2003. The Korkosz brothers built a large projector for the Boston Museum of Science, which was unique in being the first (and for a very long time only) planetarium to project the planet Uranus. Most planetariums ignore Uranus as being at best marginally visible to the naked eye.

A great boost to the popularity of the planetarium worldwide was provided by the Space Race of the 1950s and 60s when fears that the United States might miss out on the opportunities of the new frontier in space stimulated a massive program to install over 1,200 planetariums in U.S. high schools.

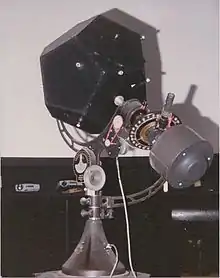

Armand Spitz recognized that there was a viable market for small inexpensive planetaria. His first model, the Spitz A, was designed to project stars from a dodecahedron, thus reducing machining expenses in creating a globe.[11] Planets were not mechanized, but could be shifted by hand. Several models followed with various upgraded capabilities, until the A3P, which projected well over a thousand stars, had motorized motions for latitude change, daily motion, and annual motion for Sun, Moon (including phases), and planets. This model was installed in hundreds of high schools, colleges, and even small museums from 1964 to the 1980s.

Japan entered the planetarium manufacturing business in the 1960s, with Goto and Minolta both successfully marketing a number of different models. Goto was particularly successful when the Japanese Ministry of Education put one of their smallest models, the E-3 or E-5 (the numbers refer to the metric diameter of the dome) in every elementary school in Japan.

Phillip Stern, as former lecturer at New York City's Hayden Planetarium, had the idea of creating a small planetarium which could be programmed. His Apollo model was introduced in 1967 with a plastic program board, recorded lecture, and film strip. Unable to pay for this himself, Stern became the head of the planetarium division of Viewlex, a mid-size audio-visual firm on Long Island. About thirty canned programs were created for various grade levels and the public, while operators could create their own or run the planetarium live. Purchasers of the Apollo were given their choice of two canned shows, and could purchase more. A few hundred were sold, but in the late 1970s Viewlex went bankrupt for reasons unrelated to the planetarium business.

During the 1970s, the OmniMax movie system (now known as IMAX Dome) was conceived to operate on planetarium screens. More recently, some planetariums have re-branded themselves as dome theaters, with broader offerings including wide-screen or "wraparound" films, fulldome video, and laser shows that combine music with laser-drawn patterns.

Learning Technologies Inc. in Massachusetts offered the first easily portable planetarium in 1977. Philip Sadler designed this patented system which projected stars, constellation figures from many mythologies, celestial coordinate systems, and much else, from removable cylinders (Viewlex and others followed with their own portable versions).

When Germany reunified in 1989, the two Zeiss firms did likewise, and expanded their offerings to cover many different size domes.

Computerized planetaria

In 1983, Evans & Sutherland installed the first digital planetarium projector displaying computer graphics (Hansen planetarium, Salt Lake City, Utah)—the Digistar I projector used a vector graphics system to display starfields as well as line art. This gives the operator great flexibility in showing not only the modern night sky as visible from Earth, but as visible from points far distant in space and time. The newest generations of planetarium projectors, beginning with Digistar 3, offer fulldome video technology. This allows for the projection of any image.

Technology

Domes

- Examples of planetarium domes

The dome of the Vilnius University Planetarium.

The dome of the Vilnius University Planetarium. The dome of the Athens Planetarium.

The dome of the Athens Planetarium. The Hamburg Planetarium

The Hamburg Planetarium The Large Zeiss Planetarium in Berlin, 1987.

The Large Zeiss Planetarium in Berlin, 1987. Inside of the Planetarium located in the Science Factory (Vitenfabrikken) in Sandnes, Norway.

Inside of the Planetarium located in the Science Factory (Vitenfabrikken) in Sandnes, Norway. Dome of the Planetarium Science Center of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina

Dome of the Planetarium Science Center of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina A small inflatable portable planetarium dome.

A small inflatable portable planetarium dome. GM-II starfield projector at Priyadarshini Planetarium, Trivandrum, India

GM-II starfield projector at Priyadarshini Planetarium, Trivandrum, India Priyadarshini Planetarium, Trivandrum, India

Priyadarshini Planetarium, Trivandrum, India Tycho Brahe Planetarium, Copenhagen, Denmark

Tycho Brahe Planetarium, Copenhagen, Denmark

Planetarium domes range in size from 3 to 35 m in diameter, accommodating from 1 to 500 people. They can be permanent or portable, depending on the application.

- Portable inflatable domes can be inflated in minutes. Such domes are often used for touring planetariums visiting, for example, schools and community centres.

- Temporary structures using glass-reinforced plastic (GRP) segments bolted together and mounted on a frame are possible. As they may take some hours to construct, they are more suitable for applications such as exhibition stands, where a dome will stay up for a period of at least several days.

- Negative-pressure inflated domes are suitable in some semi-permanent situations. They use a fan to extract air from behind the dome surface, allowing atmospheric pressure to push it into the correct shape.

- Smaller permanent domes are frequently constructed from glass reinforced plastic. This is inexpensive but, as the projection surface reflects sound as well as light, the acoustics inside this type of dome can detract from its utility. Such a solid dome also presents issues connected with heating and ventilation in a large-audience planetarium, as air cannot pass through it.

- Older planetarium domes were built using traditional construction materials and surfaced with plaster. This method is relatively expensive and suffers the same acoustic and ventilation issues as GRP.

- Most modern domes are built from thin aluminium sections with ribs providing a supporting structure behind.[13] The use of aluminium makes it easy to perforate the dome with thousands of tiny holes. This reduces the reflectivity of sound back to the audience (providing better acoustic characteristics), lets a sound system project through the dome from behind (offering sound that seems to come from appropriate directions related to a show), and allows air circulation through the projection surface for climate control.

The realism of the viewing experience in a planetarium depends significantly on the dynamic range of the image, i.e., the contrast between dark and light. This can be a challenge in any domed projection environment, because a bright image projected on one side of the dome will tend to reflect light across to the opposite side, "lifting" the black level there and so making the whole image look less realistic. Since traditional planetarium shows consisted mainly of small points of light (i.e., stars) on a black background, this was not a significant issue, but it became an issue as digital projection systems started to fill large portions of the dome with bright objects (e.g., large images of the sun in context). For this reason, modern planetarium domes are often not painted white but rather a mid grey colour, reducing reflection to perhaps 35-50%. This increases the perceived level of contrast.

A major challenge in dome construction is to make seams as invisible as possible. Painting a dome after installation is a major task, and if done properly, the seams can be made almost to disappear.

Traditionally, planetarium domes were mounted horizontally, matching the natural horizon of the real night sky. However, because that configuration requires highly inclined chairs for comfortable viewing "straight up", increasingly domes are being built tilted from the horizontal by between 5 and 30 degrees to provide greater comfort. Tilted domes tend to create a favoured "sweet spot" for optimum viewing, centrally about a third of the way up the dome from the lowest point. Tilted domes generally have seating arranged stadium-style in straight, tiered rows; horizontal domes usually have seats in circular rows, arranged in concentric (facing center) or epicentric (facing front) arrays.

planetaria occasionally include controls such as buttons or joysticks in the arm rests of seats to allow audience feedback that influences the show in real time.

Often around the edge of the dome (the "cove") are:

- Silhouette models of geography or buildings like those in the area round the planetarium building.

- Lighting to simulate the effect of twilight or urban light pollution.

- In one planetarium the horizon decor included a small model of a UFO flying.

Traditionally, planetariums needed many incandescent lamps around the cove of the dome to help audience entry and exit, to simulate sunrise and sunset, and to provide working light for dome cleaning. More recently, solid-state LED lighting has become available that significantly decreases power consumption and reduces the maintenance requirement as lamps no longer have to be changed on a regular basis.

The world's largest mechanical planetarium is located in Monico, Wisconsin. The Kovac Planetarium. It is 22 feet in diameter and weighs two tons. The globe is made of wood and is driven with a variable speed motor controller. This is the largest mechanical planetarium in the world, larger than the Atwood Globe in Chicago (15 feet in diameter) and one third the size of the Hayden.

Some new planetariums now feature a glass floor, which allows spectators to stand near the center of a sphere surrounded by projected images in all directions, giving the impression of floating in outer space. For example, a small planetarium at AHHAA in Tartu, Estonia features such an installation, with special projectors for images below the feet of the audience, as well as above their heads.[14]

Traditional electromechanical/optical projectors

Traditional planetarium projection apparatus use a hollow ball with a light inside, and a pinhole for each star, hence the name "star ball". With some of the brightest stars (e.g. Sirius, Canopus, Vega), the hole must be so big to let enough light through that there must be a small lens in the hole to focus the light to a sharp point on the dome. In later and modern planetarium star balls, the individual bright stars often have individual projectors, shaped like small hand-held torches, with focusing lenses for individual bright stars. Contact breakers prevent the projectors from projecting below the "horizon".

The star ball is usually mounted so it can rotate as a whole to simulate the Earth's daily rotation, and to change the simulated latitude on Earth. There is also usually a means of rotating to produce the effect of precession of the equinoxes. Often, one such ball is attached at its south ecliptic pole. In that case, the view cannot go so far south that any of the resulting blank area at the south is projected on the dome. Some star projectors have two balls at opposite ends of the projector like a dumbbell. In that case all stars can be shown and the view can go to either pole or anywhere between. But care must be taken that the projection fields of the two balls match where they meet or overlap.

Smaller planetarium projectors include a set of fixed stars, Sun, Moon, and planets, and various nebulae. Larger projectors also include comets and a far greater selection of stars. Additional projectors can be added to show twilight around the outside of the screen (complete with city or country scenes) as well as the Milky Way. Others add coordinate lines and constellations, photographic slides, laser displays, and other images.

Each planet is projected by a sharply focused spotlight that makes a spot of light on the dome. Planet projectors must have gearing to move their positioning and thereby simulate the planets' movements. These can be of these types:-

- Copernican. The axis represents the Sun. The rotating piece that represents each planet carries a light that must be arranged and guided to swivel so it always faces towards the rotating piece that represents the Earth. This presents mechanical problems including:

- The planet lights must be powered by wires, which have to bend about as the planets rotate, and repeatedly bending copper wire tends to cause wire breakage through metal fatigue.

- When a planet is at opposition to the Earth, its light is liable to be blocked by the mechanism's central axle. (If the planet mechanism is set 180° rotated from reality, the lights are carried by the Earth and shine towards each planet, and the blocking risk happens at conjunction with Earth.)

- Ptolemaic. Here the central axis represents the Earth. Each planet light is on a mount which rotates only about the central axis, and is aimed by a guide which is steered by a deferent and an epicycle (or whatever the planetarium maker calls them). Here Ptolemy's number values must be revised to remove the daily rotation, which in a planetarium is catered for otherwise. (In one planetarium, this needed Ptolemaic-type orbital constants for Uranus, which was unknown to Ptolemy.)

- Computer-controlled. Here all the planet lights are on mounts which rotate only about the central axis, and are aimed by a computer.

Despite offering a good viewer experience, traditional star ball projectors suffer several inherent limitations. From a practical point of view, the low light levels require several minutes for the audience to "dark adapt" its eyesight. "Star ball" projection is limited in education terms by its inability to move beyond an earth-bound view of the night sky. Finally, in most traditional projectors the various overlaid projection systems are incapable of proper occultation. This means that a planet image projected on top of a star field (for example) will still show the stars shining through the planet image, degrading the quality of the viewing experience. For related reasons, some planetariums show stars below the horizon projecting on the walls below the dome or on the floor, or (with a bright star or a planet) shining in the eyes of someone in the audience.

However, the new breed of Optical-Mechanical projectors using fiber-optic technology to display the stars show a much more realistic view of the sky.

Digital projectors

An increasing number of planetariums are using digital technology to replace the entire system of interlinked projectors traditionally employed around a star ball to address some of their limitations. Digital planetarium manufacturers claim reduced maintenance costs and increased reliability from such systems compared with traditional "star balls" on the grounds that they employ few moving parts and do not generally require synchronisation of movement across the dome between several separate systems. Some planetariums mix both traditional opto-mechanical projection and digital technologies on the same dome.

In a fully digital planetarium, the dome image is generated by a computer and then projected onto the dome using a variety of technologies including cathode ray tube, LCD, DLP, or laser projectors. Sometimes a single projector mounted near the centre of the dome is employed with a fisheye lens to spread the light over the whole dome surface, while in other configurations several projectors around the horizon of the dome are arranged to blend together seamlessly.

Digital projection systems all work by creating the image of the night sky as a large array of pixels. Generally speaking, the more pixels a system can display, the better the viewing experience. While the first generation of digital projectors were unable to generate enough pixels to match the image quality of the best traditional "star ball" projectors, high-end systems now offer a resolution that approaches the limit of human visual acuity.

LCD projectors have fundamental limits on their ability to project true black as well as light, which has tended to limit their use in planetaria. LCOS and modified LCOS projectors have improved on LCD contrast ratios while also eliminating the “screen door” effect of small gaps between LCD pixels. “Dark chip” DLP projectors improve on the standard DLP design and can offer relatively inexpensive solution with bright images, but the black level requires physical baffling of the projectors. As the technology matures and reduces in price, laser projection looks promising for dome projection as it offers bright images, large dynamic range and a very wide color space.

Show content

Worldwide, most planetariums provide shows to the general public. Traditionally, shows for these audiences with themes such as "What's in the sky tonight?", or shows which pick up on topical issues such as a religious festival (often the Christmas star) linked to the night sky, have been popular. Live format is preferred by many venues as a live speaker or presenter can answer questions raised by the audience.

Since the early 1990s, fully featured 3-D digital planetariums have added an extra degree of freedom to a presenter giving a show because they allow simulation of the view from any point in space, not only the Earth-bound view which we are most familiar with. This new virtual reality capability to travel through the universe provides important educational benefits because it vividly conveys that space has depth, helping audiences to leave behind the ancient misconception that the stars are stuck on the inside of a giant celestial sphere and instead to understand the true layout of the Solar System and beyond. For example, a planetarium can now 'fly' the audience towards one of the familiar constellations such as Orion, revealing that the stars which appear to make up a co-ordinated shape from our earth-bound viewpoint are at vastly different distances from Earth and so not connected, except in human imagination and mythology. For especially visual or spatially aware people, this experience can be more educationally beneficial than other demonstrations.

See also

- Antikythera mechanism

- Armillary sphere

- Astrarium

- Astrolabe

- Astronomical clock

- Fulldome video

- List of observatory software

- List of planetariums

- Observatory

- Orrery

- Planetarium projector

- Prague Orloj

- Torquetum

- Star atlas

- Space-themed music

References

- King, Henry C. "Geared to the Stars; the evolution of planetariums, orreries, and astronomical clocks" University of Toronto Press, 1978

- Directory of Planetariums, 2005, International Planetarium Society

- Catalog of New York Planetariums, 1982

- "Birla Planetarium ready to welcome visitors after 28-month break - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- "PlanetariumVR".

- Marche, Jordan (2005). Theaters of Time and Space: American Planetaria, 1930-1970. Rutgers: Rutgers University Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780813537665. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- "History of Planetariums". commons.bcit.ca. Retrieved 2022-10-27.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Eise Eisinga Planetarium". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2022-10-27.

- Engber, Daniel (24 February 2014). "Under the Dome: The tragic, untold story of the world's first planetarium". Slate. The Slate Group. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- Chartrand, Mark (September 1973). "A Fifty Year Anniversary of a Two Thousand Year Dream (The History of the Planetarium)". The Planetarian. Vol. 2, no. 3. International Planetarium Society. ISSN 0090-3213. Archived from the original on 2009-04-20. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- Ley, Willy (February 1965). "Forerunners of the Planetarium". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 87–98.

- "- Bhasani Novo Theatre". www.mosict.gov.bd. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- "ESOblog: How to Install a Planetarium A conversation with engineer Max Rößner about his work on the ESO Supernova". www.eso.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- Aru, Margus (March–June 2012). "Under One Dome: AHHAA Science Centre Planetarium" (PDF). Planetarian: Journal of the International Planetarium Society. 41 (2): 37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-10-02. Retrieved 2017-06-02.