Poetics (Aristotle)

Aristotle's Poetics (Greek: Περὶ ποιητικῆς Peri poietikês; Latin: De Poetica;[1] c. 335 BC[2]) is the earliest surviving work of Greek dramatic theory and first extant philosophical treatise to focus on literary theory.[3] In this text Aristotle offers an account of ποιητική, which refers to poetry and more literally "the poetic art," deriving from the term for "poet; author; maker," ποιητής. Aristotle divides the art of poetry into verse drama (to include comedy, tragedy, and the satyr play), lyric poetry, and epic. The genres all share the function of mimesis, or imitation of life, but differ in three ways that Aristotle describes:

- Differences in music rhythm, harmony, meter and melody.

- Difference of goodness in the characters.

- Difference in how the narrative is presented: telling a story or acting it out.

| Part of a series on the |

| Corpus Aristotelicum |

|---|

|

| Logic (Organon) |

|

| Natural philosophy (physics) |

|

| Metaphysics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Other links |

|

|

[*]: Generally agreed to be spurious [†]: Authenticity disputed |

The surviving book of Poetics is primarily concerned with drama, and the analysis of tragedy constitutes the core of the discussion.[4][5]

Although the text is universally acknowledged in the Western critical tradition, "almost every detail about [t]his seminal work has aroused divergent opinions".[6] Among scholarly debates on the Poetics, the three most prominent have concerned the meanings of catharsis and hamartia (these being the best known), and the question why Aristotle appears to contradict himself between chapters 13 and 14.[7][8]

Background

Aristotle's work on aesthetics consists of the Poetics, Politics (Bk VIII) and Rhetoric.[9][10] The Poetics was lost to the Western world for a long time. The text was restored to the West in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance only through a Latin translation of an Arabic version written by Averroes.[11] The accurate Greek-Latin translation made by William of Moerbeke in 1278 was virtually ignored.[12] At some point during antiquity, the original text of the Poetics was divided in two, each "book" written on a separate roll of papyrus.[13] Only the first part – that which focuses on tragedy and epic (as a quasi-dramatic art, given its definition in Ch 23) – survives. The lost second part addressed comedy.[13][14] Some scholars speculate that the Tractatus coislinianus summarises the contents of the lost second book.[15]

Overview

The table of contents page of the Poetics found in Modern Library's Basic Works of Aristotle (2001) identifies five basic parts within it.[16]

- A. Preliminary discourse on tragedy, epic poetry, and comedy, as the chief forms of imitative poetry.

- B. Definition of a tragedy, and the rules for its construction. Definition and analysis into qualitative parts.

- C. Rules for the construction of a tragedy: Tragic pleasure, or catharsis experienced by fear and pity should be produced in the spectator. The characters must be four things: good, appropriate, realistic, and consistent. Discovery must occur within the plot. Narratives, stories, structures and poetics overlap. It is important for the poet to visualize all of the scenes when creating the plot. The poet should incorporate complication and dénouement within the story, as well as combine all of the elements of tragedy. The poet must express thought through the characters' words and actions, while paying close attention to diction and how a character's spoken words express a specific idea. Aristotle believed that all of these different elements had to be present in order for the poetry to be well-done.

- D. Possible criticisms of an epic or tragedy, and the answers to them.

- E. Tragedy as artistically superior to epic poetry: Tragedy has everything that the epic has, even the epic meter being admissible. The reality of presentation is felt in the play as read, as well as in the play as acted. The tragic imitation requires less time for the attainment of its end. If it has more concentrated effect, it is more pleasurable than one with a large admixture of time to dilute it. There is less unity in the imitation of the epic poets (plurality of actions) and this is proved by the fact that an epic poem can supply enough material for several tragedies.

Aristotle also draws a famous distinction between the tragic mode of poetry and the type of history writing practiced among the Greeks. Whereas history deals with things that took place in the past, tragedy concerns itself with what might occur, or could be imagined to happen. History deals with particulars, whose relation to one another is marked by contingency, accident or chance. Contrariwise, poetic narratives are determined objects, unified by a plot whose logic binds up the constituent elements by necessity and probability. In this sense, he concluded, such poetry was more philosophical than history in so far as it approximates to a knowledge of universals.[17]

Synopsis

Aristotle distinguishes between the genres of "poetry" in three ways:

- Matter

- language, rhythm, and melody, for Aristotle, make up the matter of poetic creation. Where the epic poem makes use of language alone, the playing of the lyre involves rhythm and melody. Some poetic forms include a blending of all materials; for example, Greek tragic drama included a singing chorus, and so music and language were all part of the performance. These points also convey the standard view. Recent work, though, argues that translating rhuthmos here as "rhythm" is absurd: melody already has its own inherent musical rhythm, and the Greek can mean what Plato says it means in Laws II, 665a: "(the name of) ordered body movement," or dance. This correctly conveys what dramatic musical creation, the topic of the Poetics, in ancient Greece had: music, dance, and language. Also, the musical instrument cited in Ch 1 is not the lyre but the kithara, which was played in the drama while the kithara-player was dancing (in the chorus), even if that meant just walking in an appropriate way. Moreover, epic might have had only literary exponents, but as Plato's Ion and Aristotle's Ch 26 of the Poetics help prove, for Plato and Aristotle at least some epic rhapsodes used all three means of mimesis: language, dance (as pantomimic gesture), and music (if only by chanting the words).[18]

- Subjects

- Also "agents" in some translations. Aristotle differentiates between tragedy and comedy throughout the work by distinguishing between the nature of the human characters that populate either form. Aristotle finds that tragedy deals with serious, important, and virtuous people. Comedy, on the other hand, treats of less virtuous people and focuses on human "weaknesses and foibles".[19] Aristotle introduces here the influential tripartite division of characters in superior (βελτίονας) to the audience, inferior (χείρονας), or at the same level (τοιούτους).[20][21][22]

- Method

- One may imitate the agents through use of a narrator throughout, or only occasionally (using direct speech in parts and a narrator in parts, as Homer does), or only through direct speech (without a narrator), using actors to speak the lines directly. This latter is the method of tragedy (and comedy): without use of any narrator.

Having examined briefly the field of "poetry" in general, Aristotle proceeds to his definition of tragedy:

Tragedy is a representation of a serious, complete action which has magnitude, in embellished speech, with each of its elements [used] separately in the [various] parts [of the play] and [represented] by people acting and not by narration, accomplishing by means of pity and terror the catharsis of such emotions.

By "embellished speech", I mean that which has rhythm and melody, i.e. song. By "with its elements separately", I mean that some [parts of it] are accomplished only by means of spoken verses, and others again by means of song (1449b25-30).[23]

He then identifies the "parts" of tragedy:

- plot (mythos)

- Refers to the "organization of incidents". It should imitate an action evoking pity and fear. The plot involves a change from bad towards good, or good towards bad. Complex plots have reversals and recognitions. These and suffering (or violence) are used to evoke the tragic emotions. The most tragic plot pushes a good character towards undeserved misfortune because of a mistake (hamartia). Plots revolving around such a mistake are more tragic than plots with two sides and an opposite outcome for the good and the bad. Violent situations are most tragic if they are between friends and family. Threats can be resolved (best last) by being done in knowledge, done in ignorance and then discovered, almost be done in ignorance but be discovered in the last moment.

- Actions should follow logically from the situation created by what has happened before, and from the character of the agent. This goes for recognitions and reversals as well, as even surprises are more satisfying to the audience if they afterwards are seen as a plausible or necessary consequence.

- Character is the moral or ethical character of the agents. It is revealed when the agent makes moral choices. In a perfect tragedy, the character will support the plot, which means personal motivations and traits will somehow connect parts of the cause-and-effect chain of actions producing pity and fear.

- Main character should be:

- good—Aristotle explains that audiences do not like, for example, villains "making fortune from misery" in the end. It might happen though, and might make the play interesting. Nevertheless, the moral is at stake here and morals are important to make people happy (people can, for example, see tragedy because they want to release their anger).

- appropriate—if a character is supposed to be wise, it is unlikely he is young (supposing wisdom is gained with age).

- consistent—if a person is a soldier, he is unlikely to be scared of blood (if this soldier is scared of blood it must be explained and play some role in the story to avoid confusing the audience); it is also "good" if a character doesn't change opinion "that much" if the play is not "driven" by who characters are, but by what they do (audience is confused in case of unexpected shifts in behaviour [and its reasons and morals] of characters).

- "consistently inconsistent"—if a character always behaves foolishly it is strange if he suddenly becomes intelligent. In this case it would be good to explain such change, otherwise the audience may be confused. If character changes opinion a lot it should be clear he is a character who has this trait, not a real life person – this is also to avoid confusion.

- thought (dianoia)—spoken (usually) reasoning of human characters can explain the characters or story background.

- diction (lexis) Lexis is better translated according to some as "speech" or "language." Otherwise, the relevant necessary condition stemming from logos in the definition (language) has no followup: mythos (plot) could be done by dancers or pantomime artists, given Chs 1, 2 and 4, if the actions are structured (on stage, as drama was usually done), just like plot for us can be given in film or in a story-ballet with no words.

- Refers to the quality of speech in tragedy. Speeches should reflect character, the moral qualities of those on the stage. The expression of the meaning of the words.

- melody (melos) "Melos" can also mean "music-dance" as some musicologists recognize, especially given that its primary meaning in ancient Greek is "limb" (an arm or a leg). This is arguably more sensible because then Aristotle is conveying what the chorus actually did.[24]

- The Chorus too should be regarded as one of the actors. It should be an integral part of the whole, and share in the action. Should be contributed to the unity of the plot. It is a very real factor in the pleasure of the drama.

- spectacle (opsis)

- Refers to the visual apparatus of the play, including set, costumes and props (anything you can see). Aristotle calls spectacle the "least artistic" element of tragedy, and the "least connected with the work of the poet (playwright). For example: if the play has "beautiful" costumes and "bad" acting and "bad" story, there is "something wrong" with it. Even though that "beauty" may save the play it is "not a nice thing".

He offers the earliest-surviving explanation for the origins of tragedy and comedy:

Anyway, arising from an improvisatory beginning (both tragedy and comedy—tragedy from the leaders of the dithyramb, and comedy from the leaders of the phallic processions which even now continue as a custom in many of our cities) [...] (1449a10-13)[25]

Influence

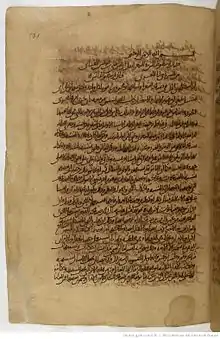

The Arabic version of Aristotle's Poetics that influenced the Middle Ages was translated from a Greek manuscript dated to some time prior to the year 700. This manuscript, translated from Greek to Syriac, is independent of the currently-accepted 11th-century source designated Paris 1741.[lower-alpha 1] The Syriac-language source used for the Arabic translations departed widely in vocabulary from the original Poetics and it initiated a misinterpretation of Aristotelian thought that continued through the Middle Ages.[26]

The scholars who published significant commentaries on Aristotle's Poetics included Avicenna, Al-Farabi and Averroes.[27] Many of these interpretations sought to use Aristotelian theory to impose morality on the Arabic poetic tradition.[28] In particular, Averroes added a moral dimension to the Poetics by interpreting tragedy as the art of praise and comedy as the art of blame.[12] Averroes' interpretation of the Poetics was accepted by the West, where it reflected the "prevailing notions of poetry" into the 16th century.[12]

Giorgio Valla's 1498 Latin translation of Aristotle's text (the first to be published) was included with the 1508 Aldine printing of the Greek original as part of an anthology of Rhetores graeci. By the early decades of the sixteenth century, vernacular versions of Aristotle's Poetics appeared, culminating in Lodovico Castelvetro's Italian editions of 1570 and 1576.[29] Italian culture produced the great Renaissance commentators on Aristotle's Poetics, and in the baroque period it was Emanuele Tesauro who, with his Cannocchiale aristotelico, re-presented to the world of post-Galilean physics Aristotle's poetic theories as the sole key to approaching the human sciences.[30]

Recent scholarship has challenged whether Aristotle focuses on literary theory per se (given that not one poem exists in the treatise) or whether he focuses instead on dramatic musical theory that only has language as one of the elements.[31]

The lost second book of Aristotle's Poetics is a core plot element (and the “MacGuffin”) in Umberto Eco's novel The Name of the Rose.

Core terms

- Mimesis or "imitation", "representation," or "expression," given that, e.g., music is a form of mimesis, and often there is no music in the real world to be "imitated" or "represented."

- Hubris or Hybris, "pride"

- Nemesis or, "retribution"

- Hamartia or "miscalculation" (understood in Romanticism as "tragic flaw")

- Anagnorisis or "recognition", "identification"

- Peripeteia or "reversal"

- Catharsis or, variously, "purgation", "purification", "clarification"

- Mythos or "plot," defined in Ch 6 explicitly as the "structure of actions."

- Ethos or "character"

- Dianoia or "thought", "theme"

- Lexis or "diction", "speech"

- Melos, or "melody"; also "music-dance" (melos meaning primarily "limb")

- Opsis or "spectacle"

Editions – commentaries – translations

- Aristotle's Treatise on Poetry, transl. with notes by Th. Twining, I-II, London 21812

- Aristotelis De arte poetica liber, tertiis curis recognovit et adnotatione critica auxit I. Vahlen, Lipsiae 31885

- Aristotle on the Art of Poetry. A revised Text with Critical Introduction, Translation and Commentary by I. Bywater, Oxford 1909

- Aristoteles: Περὶ ποιητικῆς, mit Einleitung, Text und adnotatio critica, exegetischem Kommentar [...] von A. Gudeman, Berlin/Leipzig 1934

- Ἀριστοτέλους Περὶ ποιητικῆς, μετάφρασις ὑπὸ Σ. Μενάρδου, Εἰσαγωγή, κείμενον καὶ ἑρμηνεία ὑπὸ Ἰ. Συκουτρῆ, (Ἀκαδ. Ἀθηνῶν, Ἑλληνική Βιβλιοθήκη 2), Ἀθῆναι 1937

- Aristotele: Poetica, introduzione, testo e commento di A. Rostagni, Torino 21945

- Aristotle's Poetics: The Argument, by G. F. Else, Harvard 1957

- Aristotelis De arte poetica liber, recognovit brevique adnotatione critica instruxit R. Kassel, Oxonii 1965

- Aristotle: Poetics, Introduction, Commentary and Appendixes by D. W. Lucas, Oxford 1968

- Aristotle: Poetics, with Tractatus Coislinianus, reconstruction of Poetics II, and the Fragments of the On the Poets, transl. by R. Janko, Indianapolis/Cambridge 1987

- Aristotle: Poetics, edited and translated by St. Halliwell, (Loeb Classical Library), Harvard 1995

- Aristote: Poétique, trad. J. Hardy, Gallimard, collection tel, Paris, 1996.

- Aristotle: Poetics, translated with an introduction and notes by M. Heath, (Penguin) London 1996

- Aristoteles: Poetik, (Werke in deutscher Übersetzung 5) übers. von A. Schmitt, Darmstadt 2008

- Aristotle: Poetics, editio maior of the Greek text with historical introductions and philological commentaries by L. Tarán and D. Goutas, (Mnemosyne Supplements 338) Leiden/Boston 2012

Other English translations

- Thomas Twining, 1789

- Samuel Henry Butcher, 1902: full text

- Ingram Bywater, 1909: full text

- William Hamilton Fyfe, 1926: full text

- L. J. Potts, 1953

- G. M. A. Grube, 1958

- Gerald F. Else, 1967 (University of Michigan Press)

- Leon Golden and O.B. Hardison, 1968 (Florida State UP)

- Richard Janko, 1987

- Stephen Halliwell, 1987

- Hippocrates G. Apostle, 1990

- Stephen Halliwell, 1995 (Loeb Classical Library)

- Malcolm Heath, 1996 (Penguin Classics)

- George Whalley, 1997 (posthumous, McGill-Queen's University Press)

- Seth Benardete and Michael Davis, 2002 (St. Augustine's Press)

- Joe Sachs, 2006 (Focus Publishing)

- Anthony Kenny, 2013 (Oxford World's Classics)

- Rune Myrland, 2018 (Storyknot)

Notes

- A digital reproduction of Paris 1741 is available on the website of Bibliothèque nationale de France (National Library of France): https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55005722s . The Poetics begins on page 184r

References

- Aristotelis Opera by August Immanuel Bekker (1837).

- Dukore (1974, 31).

- Janko (1987, ix).

- Aristotle Poetics 1447a13 (1987, 1).

- Battin, M. Pabst (1974). "Aristotle's Definition of Tragedy in the Poetics". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 33 (2): 155–170. doi:10.2307/429084. ISSN 0021-8529. JSTOR 429084.

- Carlson (1993, 16).

- John Moles, 'Notes on Aristotle, Poetics 13 and 14,' The Classical Quarterly 1979 Vol. 29, No. 1 1979, pp. 77-94

- Sheila Murnaghan, 'Sucking the Juice without Biting the Rind: Aristotle and Tragic Mimēsis,' New Literary History Autumn 1995 ol. 26, No. 4, pp. 755-773.

- Garver, Eugene (1994). Aristotle's Rhetoric: An Art of Character. p. 3. ISBN 0226284247.

- Haskins, Ekaterina V. (2004). Logos and Power in Isocrates and Aristotle. pp. 31ff. ISBN 1570035261.

- Habib, M.A.R. (2005). A History of Literary Criticism and Theory: From Plato to the Present. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 60. ISBN 0-631-23200-1.

- Kennedy, George Alexander; Norton, Glyn P. (1999). The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 0521300088.

- Janko (1987, xx).

- Watson, Walter (2015-03-23). The Lost Second Book of Aristotle's "Poetics". University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-27411-9.

- Janko (1987, xxi).

- The Basic Works of Aristotle. Ed. Richard McKeon Modern Library (2001) – Poetics. Trans. Ingrid Bywater, pp. 1453–87

- Silvia Carli, Poetry is more philosophical than history: Aristotle on mimesis and form, The Review of Metaphysics, December 2010, Vol. 64, No. 2 pp. 303-336, esp.pp.303-304,312-313.

- Scott (2018)

- Halliwell, Stephen (1986). Aristotle's Poetics. p. 270. ISBN 0226313948.

- Gregory Michael Sifakis (2001) Aristotle on the function of tragic poetry p. 50

- Aristotle, Poetics 1448a, English, original Greek

- Northrop Frye (1957). Anatomy of Criticism.

- Janko (1987, 7). In Butcher's translation, this passage reads: "Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play, in the form of action, not of narrative; through pity and fear effecting the proper catharsis of these emotions."

- Scott 2019

- Janko (1987, 6). This text is available online in an older translation, in which the same passage reads: "At any rate it originated in improvisation—both tragedy itself and comedy. The one tragedy came from the prelude to the dithyramb and the other comedy from the prelude to the phallic songs which still survive as institutions in many cities."

- Hardison, 81.

- Ezzaher, Lahcen E. (2013). "Arabic Rhetoric". In Enos, Theresa (ed.). Encyclopedia of Rhetoric and Composition. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-1135816063.

- Ezzaher 2013, p. 15.

- Minor, Vernon Hyde (2016). Baroque Visual Rhetoric. University of Toronto Press. p. 13. ISBN 1442648791.

- Eco, Umberto (2004). On literature. Harcourt. p. 236. ISBN 9780151008124.

- Destrée (2016); Scott (2018).

Sources

- Belfiore, Elizabeth, S., Tragic Pleasures: Aristotle on Plot and Emotion. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton UP (1992). ISBN 0-691-06899-2

- Bremer, J.M., Hamartia: Tragic Error in the Poetics of Aristotle and the Greek Tragedy, Amsterdam 1969

- Butcher, Samuel H., Aristotle's Theory of Poetry and Fine Art, New York 41911

- Carroll, M., Aristotle's Poetics, c. xxv, Ιn the Light of the Homeric Scholia, Baltimore 1895

- Cave, Terence, Recognitions. A Study in Poetics, Oxford 1988

- Carlson, Marvin, Theories of the Theatre: A Historical and Critical Survey from the Greeks to the Present. Expanded ed. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP (1993). ISBN 978-0-8014-8154-3.

- Destrée, Pierre, "Aristotle on the Power of Music in Tragedy," Greek & Roman Musical Studies, Vol. 4, Issue 2, 2016

- Dukore, Bernard F., Dramatic Theory and Criticism: Greeks to Grotowski. Florence, KY: Heinle & Heinle (1974). ISBN 0-03-091152-4

- Downing, E., "oἷον ψυχή: Αn Εssay on Aristotle's muthos", Classical Antiquity 3 (1984) 164-78

- Else, Gerald F., Plato and Aristotle on Poetry, Chapel Hill/London 1986

- Heath, Malcolm (1989). "Aristotelian Comedy". Classical Quarterly. 39 (1989): 344–354. doi:10.1017/S0009838800037411. S2CID 246879371.

- Heath, Malcolm (1991). "The Universality of Poetry in Aristotle's Poetics". Classical Quarterly. 41 (1991): 389–402. doi:10.1017/S0009838800004559.

- Heath, Malcolm (2009). "Cognition in Aristotle's Poetics". Mnemosyne. 62 (2009): 51–75. doi:10.1163/156852508X252876.

- Halliwell, Stephen, Aristotle's Poetics, Chapel Hill 1986.

- Halliwell, Stephen, The Aesthetics of Mimesis. Ancient Texts and Modern Problems, Princeton/Oxford 2002.

- Hardison, O. B., Jr., "Averroes", in Medieval Literary Criticism: Translations and Interpretations. New York: Ungar (1987), 81–88.

- Hiltunen, Ari, Aristotle in Hollywood. Intellect (2001). ISBN 1-84150-060-7.

- Ηöffe, O. (ed.), Aristoteles: Poetik, (Klassiker auslegen, Band 38) Berlin 2009

- Janko, R., Aristotle on Comedy, London 1984

- Jones, John, On Aristotle and Greek Tragedy, London 1971

- Lanza, D. (ed.), La poetica di Aristotele e la sua storia, Pisa 2002

- Leonhardt, J., Phalloslied und Dithyrambos. Aristoteles über den Ursprung des griechischen Dramas. Heidelberg 1991

- Lienhard, K., Entstehung und Geschichte von Aristoteles ‘Poetik’, Zürich 1950

- Lord, C., "Aristotle's History of Poetry", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 104 (1974) 195–228

- Lucas, F. L., Tragedy: Serious Drama in Relation to Aristotle's "Poetics". London: Hogarth (1957). New York: Collier. ISBN 0-389-20141-3. London: Chatto. ISBN 0-7011-1635-8

- Luserke, M. (ed.), Die aristotelische Katharsis. Dokumente ihrer Deutung im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Hildesheim/Zürich/N. York 1991

- Morpurgo- Tagliabue, G., Linguistica e stilistica di Aristotele, Rome 1967

- Rorty, Amélie Oksenberg (ed.), Essays on Aristotle's Poetics, Princeton 1992

- Schütrumpf, E., "Traditional Elements in the Concept of Hamartia in Aristotle's Poetics", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 92 (1989) 137–56

- Scott, Gregory L., Aristotle on Dramatic Musical Composition The Real Role of Literature, Catharsis, Music and Dance in the Poetics (2018b), ISBN 978-0999704936

- Scott, Gregory, "Aristotle on Dramatic Musical Composition," in Ancient Philosophy Volume 39, Issue 1, Spring 2019, 248–252, https://doi.org/10.5840/ancientphil201939117

- Sen, R. K., Mimesis, Calcutta: Syamaprasad College, 2001

- Sen, R. K., Aesthetic Enjoyment: Its Background in Philosophy and Medicine, Calcutta: University of Calcutta, 1966

- Sifakis, Gr. M., Aristotle on the Function of Tragic Poetry, Heraklion 2001. ISBN 960-524-132-3

- Söffing, W., Deskriptive und normative Bestimmungen in der Poetik des Aristoteles, Amsterdam 1981

- Sörbom, G., Mimesis and Art, Uppsala 1966

- Solmsen, F., "The Origins and Methods of Aristotle's Poetics", Classical Quarterly 29 (1935) 192–201

- Tsitsiridis, S., "Mimesis and Understanding. An Interpretation of Aristotle's Poetics 4.1448b4-19", Classical Quarterly 55 (2005) 435–46

- Vahlen, Johannes, Beiträge zu Aristoteles’ Poetik, Leipzig/Berlin 1914

- Vöhler, M. – Seidensticker B. (edd.), Katharsiskonzeptionen vor Aristoteles: zum kulturellen Hintergrund des Tragödiensatzes, Berlin 2007

External links

- librivox.org audio recording

- Project Gutenberg – Poetics (Aristotle)

- Aristotle's Poetics: Perseus Digital Library edition

- Greek text from Hodoi elektronikai

- Critical edition (Oxford Classical Texts) by Ingram Bywater

- Seven parallel translations of Poetics: Russian, English, French

- Aristotle: Poetics entry by Joe Sachs in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Notes of Friedrich Sylburg (1536-1596) in a critical edition (parallel Greek and Latin) available at Google Books

- Analysis and discussion in the BBC's In Our Time series on Radio 4.