Port of Los Angeles

The Port of Los Angeles is a seaport managed by the Los Angeles Harbor Department, a unit of the City of Los Angeles. It occupies 7,500 acres (3,000 ha) of land and water with 43 miles (69 km) of waterfront and adjoins the separate Port of Long Beach. Promoted as "America's Port", the port is located in San Pedro Bay in the San Pedro and Wilmington neighborhoods of Los Angeles, approximately 20 miles (32 km) south of downtown.

| Port of Los Angeles | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Port of Los Angeles In 2008 | |

| |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| Location | Los Angeles, California |

| Coordinates | 33°43′48″N 118°15′45″W[1] |

| UN/LOCODE | US LAX |

| Details | |

| Opened | December 9, 1907 |

| Size of harbor | 3,200 acres (13 km2) |

| Land area | 4,300 acres (17 km2) |

| Size | 7,500 acres (30 km2) |

| Draft depth | −53 ft (−16 m) |

| President | Jaime L. Lee |

| Vice President | Edward Renwick |

| Commissioners | Diane L. Middleton Lucia Moreno-Linares Anthony Pirozzi Jr.[2] |

| Executive Director | Gene Seroka[3] |

| Statistics | |

| Vessel arrivals | 1,867 (CY 2019) |

| Annual cargo tonnage | 178 million metric revenue tons (FY 2019) |

| Annual container volume | 9.3 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU) (CY 2019) |

| Value of cargo | $276 billion (CY 2019) |

| Passenger traffic | 650,010 passengers (CY 2019) |

| Annual revenue | $506 million (FY 2019) |

| Website portoflosangeles | |

The cargo coming into the port represents approximately 20% of all cargo coming into the United States.[4] The port's channel depth is 53 feet (16 m). The port has 25 cargo terminals, 82 container cranes, 8 container terminals, and 113 miles (182 km) of on-dock rail. The port's top imports were furniture, automobile parts, apparel, footwear, and electronics. In 2019, the port's top exports were wastepaper, pet and animal feed, scrap metal and soybeans.[5] As of a report from the port released 2020, its top three trading partners were China (including Hong Kong), Japan, and Vietnam.[6] As of 2022, the port, together with the adjoining Port of Long Beach, are considered the least efficient ports on the planet.[7][8]

History

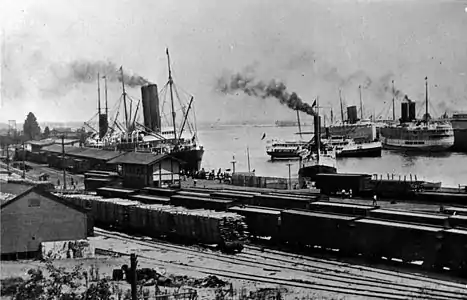

The L.A. Harbor, 1899

The L.A. Harbor, 1899 Port of Los Angeles, 1913

Port of Los Angeles, 1913

In 1542, Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo discovered the "Bay of Smokes."[9] The south-facing San Pedro Bay was originally a shallow mudflat, too soft to support a wharf. Visiting ships had two choices: stay far out at anchor and have their goods and passengers ferried to shore, or beach themselves. That sticky process is described in Two Years Before the Mast by Richard Henry Dana Jr., who was a crew member on an 1834 voyage that visited San Pedro Bay. Phineas Banning greatly improved shipping when he dredged the channel to Wilmington in 1871 to a depth of 10 feet (3.0 m). The port handled 50,000 tons of shipping that year. Banning owned a stagecoach line with routes connecting San Pedro to Salt Lake City, Utah, and Yuma, Arizona, and in 1868 he built a railroad to connect San Pedro Bay to Los Angeles, the first in the area.[10]

After Banning's death in 1885, his sons pursued their interests in promoting the port, which handled 500,000 tons of shipping in that year. The Southern Pacific Railroad and Collis P. Huntington wanted to create Port Los Angeles at Santa Monica and built the Long Wharf there in 1893. However, the Los Angeles Times publisher Harrison Gray Otis and U.S. Senator Stephen White pushed for federal support of the Port of Los Angeles at San Pedro Bay. The Free Harbor Fight was settled when San Pedro was endorsed in 1897 by a commission headed by Rear Admiral John C. Walker (who later went on to become the chair of the Isthmian Canal Commission in 1904). With U.S. government support, breakwater construction began in 1899, and the area was annexed to Los Angeles in 1909. The Los Angeles Board of Harbor Commissioners was founded in 1907.

In 1912 the Southern Pacific Railroad completed its first major wharf at the port. During the 1920s, the port surpassed San Francisco as the West Coast's busiest seaport. In the early 1930s, a massive expansion of the port was undertaken with the construction of a breakwater three miles out and over two miles in length. In addition to the construction of this outer breakwater, an inner breakwater was built off Terminal Island with docks for seagoing ships and smaller docks built at Long Beach.[11] It was this improved harbor that hosted the sailing events for the 1932 Summer Olympics.[12]

During World War II, the port was primarily used for shipbuilding, employing more than 90,000 people. In 1959, Matson Navigation Company's Hawaiian Merchant delivered 20 containers to the port, beginning the port's shift to containerization.[13] The opening of the Vincent Thomas Bridge in 1963 greatly improved access to Terminal Island and allowed increased traffic and further expansion of the port. In 1985, the port handled one million containers in a year for the first time.[9] During the 2002 West Coast port labor lockout, the port had a large backlog of ships waiting to be unloaded at any given time. Many analysts believe that the port's traffic may have exceeded its physical capacity as well as the capacity of local freeway and railroad systems. The chronic congestion at the port caused ripple effects throughout the American economy, such as disrupting just-in-time inventory practices at many companies. In 2000, the Pier 400 Dredging and Landfill Program, the largest such project in America, was completed.[9] By 2013, more than half a million containers were moving through the Port every month.[14]

Port district

The port district is an independent, self-supporting department of the government of the City of Los Angeles. The port is under the control of a five-member Board of Harbor Commissioners appointed by the mayor and approved by the city council, and is administered by an executive director. The port maintains an AA bond rating,[15] the highest rating attainable for self-funded ports.

As of 2016, the port had about a dozen pilots, including two chiefs. Pilots have specialized knowledge of the harbor and San Pedro Bay. They meet the ships waiting to enter the harbor and provide advice as the vessel is steered through the congested waterway to the dock.[16]

For public safety protection inside the port and of its businesses, the Port of Los Angeles utilizes the Los Angeles Port Police for police service, the Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD) to provide fire and EMS services, the U.S. Coast Guard for waterway security, Homeland Security to protect federal land at the port, the Los Angeles County Lifeguards to provide lifeguard services for open waters outside of the harbor, while Los Angeles City Recreation & Parks Department lifeguards patrol the inner Cabrillo Beach.

Shipping

The port's container volume was 9.3 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU) in calendar year 2019, a 5.5% increase over 2016's record-breaking year of 8.8 million TEU. It's the most cargo moved annually by a Western Hemisphere port. The port is the busiest port in the United States by container volume, the 19th-busiest container port in the world, and the 10th-busiest worldwide when combined with the neighboring Port of Long Beach. The port is also the number-one freight gateway in the United States when ranked by the value of shipments passing through it.[17] The port's top trading partners in 2019 were:

- China/Hong Kong ($128 billion)

- Japan ($89 billion)

- Vietnam ($21 billion)

- South Korea ($15 billion)

- Taiwan ($15 billion)

The most-imported types of goods in the 2019 calendar year were, in order: furniture (579,405), automobile parts (340,546), apparel (312,655), and electronic products (209,622).

The port is served by the Pacific Harbor Line (PHL) railroad. From the PHL, intermodal railroad cars go north to Los Angeles via the Alameda Corridor.

In 2011, no American port could handle ships of the PS-class Emma Mærsk and the future Maersk Triple E class size,[18] the latter of which needs cranes reaching 23 rows.[19] In 2012, the port and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers deepened the port's main navigational channel to 53 feet (16 m), which is deep enough to accommodate the draft of the world's biggest container ships.[20][21] However, Maersk had no plans in 2014 to bring those ships to America.[22]

Los Angeles and Long Beach ports are some of the least efficient in the world, according to a ranking by the World Bank and IHS Markit.[7][8]

Cruise ship terminal

The World Cruise Center, located in the San Pedro District beneath the Vincent Thomas Bridge, has three passenger ship berths[23] transporting over 1 million passengers annually, making it the largest cruise ship terminal on the West Coast of the United States. It is linked to the waterfront attractions USS Iowa Museum and Los Angeles Maritime Museum by a pedestrian promenade, as well as the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium and other San Pedro attractions by the Waterfront Red Car trolley/shuttle.

Public access investments

The LA Waterfront is a visitor-serving destination in the city of Los Angeles, funded and maintained by the Port of Los Angeles.[24] In 2009, the Los Angeles Harbor Commission approved the San Pedro Waterfront and Wilmington Waterfront development programs, under the LA Waterfront umbrella. The LA Waterfront consists of a series of waterfront development and community enhancement projects covering more than 400 acres (160 ha) of existing Port of Los Angeles property in both San Pedro and Wilmington. With miles of public promenade and walking paths, acres of open space and scenic views, the LA Waterfront attracts thousands of visitors annually. Remodel and reconstruction was approved by the Los Angeles City Council. Development is set to be completed in 2020. Construction is expected to begin in 2017 at a partial project cost of $90 million, paid by the developer. The San Pedro Public Market is expected to open in 2020, with demolition beginning as early as November 2016.[25]

The Waterfront Red Car is a currently non-operational heritage trolley line for public transit along the waterfront in San Pedro.[26] Prior to its closure in 2015, it used vintage and restored Pacific Electric Red Cars to connect the World Cruise Center, Downtown San Pedro, Ports O' Call Village, and the San Pedro Marina.[26][27][28]

Environment

Oceangoing ships visiting ports are a large source of nitrogen oxides in Southern California. Heavy-duty diesel trucks, that are also part of the freight-moving port complexes, emit exhaust with nitrogen oxides and particulate matter.[29] The California Air Resources Board is working on reducing these sources of pollution that produce the nation's most polluted air smog and kill more than 3,500 Southern Californians each year.[30] In 2021, the South Coast Air Quality Management District required warehouses in the port which do not cut emissions of carbon and pollutants to pay fees.[31][32]

The port installed the first Alternative Maritime Power (AMP) berth in 2004 and can provide up to 40 MW of grid power to two cruise ships simultaneously at both 6.6 kV and 11 kV, as well as three container terminals, reducing pollution from ship engines.[33]

In an effort to buffer the nearby community of Wilmington from the port, in June 2011 the Wilmington Waterfront Park was opened.[34][35]

Clean Air Action Program

The $2.8 million San Pedro Bay Ports Clean Air Action Program (CAAP) initiative was implemented by the Board of Harbor Commissioners in October 2002 for terminal and ship operations programs targeted at reducing polluting emissions from vessels and cargo handling equipment . To accelerate implementation of emission reductions through the use of new and cleaner-burning equipment, the port has allocated more than $52 million in additional funding for the CAAP through 2008.

As of May, 2016, the Port of Los Angeles has already surpassed its initial 2023 emission goals 8 years ahead of predicted time frame. The dramatic success to reduce emissions has seen a decrease in diesel particulate matter reduce 72%, sulfur oxides by 93%, and nitrogen oxide by 22% so far. The CAAP program was updated to 3.0 after this environmental successes of the initiatives. With the recent ramification of environment goals the updates will look to reduce the emissions through efficient supply chain optimization. There has also been recent developments to increase port technologies advancement to promote the development of efficient and green port technologies. The CAAP also looks to be the lead role caretaker of fostering and improving the wildlife and ecosystem of the port.[36]

See also

- List of ports in the United States

- Port of Long Beach

- Kenneth Hahn, youngest pilot in the history of the Port

- SS Sansinena Berth 46 incident

- SS Lane Victory a working museum ship

- USS Iowa Museum (the former USS Iowa), a World War II era battleship that permanently docked at Berth 87 since June 2012 as a museum ship.

- Port of Los Angeles Long Wharf Santa Monica

- Todd Pacific Shipyards, Los Angeles Division, a Port of Los Angeles shipyard from 1917 to 1989.

- United States container ports

References

- "Port of Los Angeles". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- "Board Members | Commission | Port of Los Angeles". www.portoflosangeles.org.

- Lopez, Ricardo (11 June 2014) "Gene Seroka named Port of Los Angeles executive director" Los Angeles Times

- Kitroeff, Natalie (April 27, 2016). "Competitors are eating into L.A. ports' dominance". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- "Facts and Figures | Statistics | Port of Los Angeles". www.portoflosangeles.org. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- Port of Los Angeles (2020). "The Port of Los Angeles – Info About the Port". The Port of Los Angeles.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Baertlein, Lisa (October 20, 2021). "California ports, key to U.S. supply chain, among world's least efficient, ranking shows". Reuters. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- Hsu, Andrea (September 11, 2022). "Before the holiday season, workers at America's busiest ports are fighting the robots". NPR.org. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are consistently rated the least efficient in the world. More modern ports in the Middle East and China, where 24/7 operations are the norm, get ships in and out much faster.

- Sowinski, L., Portrait of a Port, World Trade Magazine, February 2007, p. 32

- Estrada, Gilbert (January 24, 2014). "Brief History of the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach". KCET. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- "Big Harbor Three Miles At Sea" Popular Science, December 1931, illustration of harbor and port improvements

- 1932 Summer Olympics official report. pp. 76, 78, 585.

- Cuevas, Antonio (December 9, 2007). "Seaport's Legacy Drives Its Future". Los Angeles Times. pp. U6.

- Chinn, Kay (October 15, 2013). "L.A. Port Numbers Down From Last Year". Los Angeles Business Journal. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- "Fitch Rates Port of Los Angeles Harbor, CA's Rev Bonds 'AA'; Outlook Stable" (Press release). Fitch Ratings. August 13, 2014. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- Dolan, Jack; Pringle, Paul (June 11, 2016). "How one of L.A.'s highest-paying jobs went to the boss' son". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- "Top 25 U.S. Freight Gateways, Ranked by Value of Shipments: 2008". U.S. Department of Transportation. 2009. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- Frank Pope. "Bigger, cleaner, slower – the new giants of the seas" Mirror&Archive The Times, February 22, 2011. Accessed: 6 December 2013.

- "APM Rotterdam retrofitting cranes for more EEE calls". longshoreshippingnews.com. December 2, 2013. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- "ABS Record: Emma Maersk". American Bureau of Shipping. July 23, 2009. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- "Largest container ship will be 16% larger and 20% less CO2and 35% more fuel efficient". Next Big Future. February 21, 2011. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- Karen Robes Meeks. Ports of Long Beach, Los Angeles invest millions to accommodate ships, 2014

- "Cruise Passenger and Ferry Terminals". The Port of Los Angeles. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- "Visit the LA Waterfront at the Port of Los Angeles". www.lawaterfront.org. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- "Public Access Investment Plan" (PDF). portoflosangeles.org. February 11, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- "Attractions | LA Waterfront". www.lawaterfront.org.

- "SanPedro.com: POLA Waterfront Red Car Line - with map". sanpedro.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012.

- "RailwayPreservation.com: Port of LA Waterfront Red Car Line". Archived from the original on February 26, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- Barboza, Tony (January 3, 2020). "Port ships are becoming L.A.'s biggest polluters. Will California force a cleanup?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- Wright, Pam (August 11, 2016). "Thousands Die Each Year In Southern California From Air Pollution, Study Says". Weather.com. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "New rule requires Southern California warehouses to clean up or pay up". Yale Climate Connections. August 18, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "South Coast AQMD Governing Board Adopts Warehouse Indirect Source Rule" (PDF). South Coast Air Quality Management District. May 7, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Philips, Peter. Los Angeles Port Now Providing Shore-Side Power to Three Cruise Lines Pacific Maritime, 1 March 2011. Accessed: 1 October 2011.

- "Wilmington Waterfront Park". Port of Los Angeles. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- Landers, Jay (July 2011). "Los Angeles creates park to provide buffer between port, community". Civil Engineering Magazine: 27–30.

- "02 May Port of Los Angeles: Global Model for Sustainability & Environmental Initiatives". CFR Rinkens. CFR Rinkens. May 2, 2016. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

Further reading

- Vickery, Oliver (1979). Harbor heritage: tales of the harbor area of Los Angeles, California. Mountain View, Calif.: Morgan Press/Farag. ISBN 978-0-89430-036-3.

External links

- Official website

- Panoramic photographs of Los Angeles Harbor, taken in 1908 and 1926, The Bancroft Library

_edit1.jpg.webp)