Medical test

A medical test is a medical procedure performed to detect, diagnose, or monitor diseases, disease processes, susceptibility, or to determine a course of treatment. Medical tests such as, physical and visual exams, diagnostic imaging, genetic testing, chemical and cellular analysis, relating to clinical chemistry and molecular diagnostics, are typically performed in a medical setting.

| Medical test | |

|---|---|

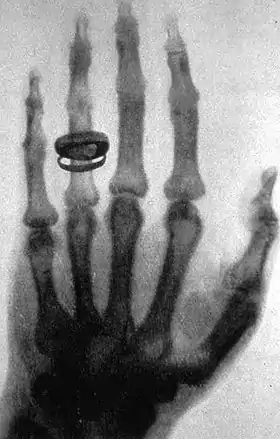

X-ray of a hand. X-rays are a common medical test. | |

| MeSH | D019937 |

Types of tests

By purpose

Medical tests can be classified by their purposes, the most common of which are diagnosis, screening and evaluation.

Diagnostic

A diagnostic test is a procedure performed to confirm or determine the presence of disease in an individual suspected of having a disease, usually following the report of symptoms, or based on other medical test results.[1][2] This includes posthumous diagnosis. Examples of such tests are:

- Using nuclear medicine to examine a patient suspected of having a lymphoma.

- Measuring the blood sugar in a person suspected of having diabetes mellitus after periods of increased urination.

- Taking a complete blood count of an individual experiencing a high fever to check for a bacterial infection.[1]

- Monitoring electrocardiogram readings on a patient with chest pain to diagnose or determine any heart irregularities.[3]

Screening

Screening refers to a medical test or series of tests used to detect or predict the presence of disease in at-risk individuals within a defined group such as a population, family, or workforce.[4][5] Screenings may be performed to monitor disease prevalence, manage epidemiology, aid in prevention, or strictly for statistical purposes.[6]

Examples of screenings include measuring the level of TSH in the blood of a newborn infant as part of newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism,[7] checking for Lung cancer in non-smoking individuals who are exposed to second-hand smoke in an unregulated working environment, and Pap smear screening for prevention or early detection of cervical cancer.

Monitoring

Some medical tests are used to monitor the progress of, or response to medical treatment.

By method

Most test methods can be classified into one of the following broad groups:

- Patient observations, which may be photographed or recorded

- Questions asked when taking an individual's medical history

- Tests performed in a physical examination

- Radiologic tests, in which, for example, x-rays are used to form an image of a body target. These tests often involve administration of a contrast agent.

- In vivo diagnostics which test in the body, such as:

- In vitro diagnostics which test a sample of tissue or bodily fluids,[9][10] such as:

- Liquid biopsy

- Microbiological culturing, which determines the presence or absence of microbes in a sample from the body, and usually targeted at detecting pathogenic bacteria.

- Genetic testing

- Blood sugar level[11]

- Liver function testing[12]

- Calcium testing[12]

- Testing for electrolytes in the blood, such as sodium, potassium, creatinine, and urea[13]

By sample location

In vitro tests can be classified according to the location of the sample being tested, including:

- Blood tests

- Urine tests, including naked eye exam of the urine

- Stool tests, including naked eye exam of the feces

- Sputum (phlegm), including naked eye exam of the sputum

Accuracy and precision

- Accuracy of a laboratory test is its correspondence with the true value. Accuracy is maximized by calibrating laboratory equipment with reference material and by participating in external quality control programs.

- Precision of a test is its reproducibility when it is repeated on the same sample. An imprecise test yields widely varying results on repeated measurement. Precision is monitored in laboratory by using control material.

Detection and quantification

Tests performed in a physical examination are usually aimed at detecting a symptom or sign, and in these cases, a test that detects a symptom or sign is designated a positive test, and a test that indicated absence of a symptom or sign is designated a negative test, as further detailed in a separate section below.A quantification of a target substance, a cell type or another specific entity is a common output of, for example, most blood tests. This is not only answering if a target entity is present or absent, but also how much is present. In blood tests, the quantification is relatively well specified, such as given in mass concentration, while most other tests may be quantifications as well although less specified, such as a sign of being "very pale" rather than "slightly pale". Similarly, radiologic images are technically quantifications of radiologic opacity of tissues.

Especially in the taking of a medical history, there is no clear limit between a detecting or quantifying test versus rather descriptive information of an individual. For example, questions regarding the occupation or social life of an individual may be regarded as tests that can be regarded as positive or negative for the presence of various risk factors, or they may be regarded as "merely" descriptive, although the latter may be at least as clinically important.

Positive or negative

The result of a test aimed at detection of an entity may be positive or negative: this has nothing to do with a bad prognosis, but rather means that the test worked or not, and a certain parameter that was evaluated was present or not. For example, a negative screening test for breast cancer means that no sign of breast cancer could be found (which is in fact very positive for the patient).

The classification of tests into either positive or negative gives a binary classification, with resultant ability to perform bayesian probability and performance metrics of tests, including calculations of sensitivity and specificity.

Continuous values

Tests whose results are of continuous values, such as most blood values, can be interpreted as they are, or they can be converted to a binary ones by defining a cutoff value, with test results being designated as positive or negative depending on whether the resultant value is higher or lower than the cutoff.

Interpretation

In the finding of a pathognomonic sign or symptom it is almost certain that the target condition is present, and in the absence of finding a sine qua non sign or symptom it is almost certain that the target condition is absent. In reality, however, the subjective probability of the presence of a condition is never exactly 100% or 0%, so tests are rather aimed at estimating a post-test probability of a condition or other entity.

Most diagnostic tests basically use a reference group to establish performance data such as predictive values, likelihood ratios and relative risks, which are then used to interpret the post-test probability for an individual.

In monitoring tests of an individual, the test results from previous tests on that individual may be used as a reference to interpret subsequent tests.

Risks

Some medical testing procedures have associated health risks, and even require general anesthesia, such as the mediastinoscopy.[14] Other tests, such as the blood test or pap smear have little to no direct risks.[15] Medical tests may also have indirect risks, such as the stress of testing, and riskier tests may be required as follow-up for a (potentially) false positive test result. Consult the health care provider (including physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) prescribing any test for further information.

Indications

Each test has its own indications and contraindications. An indication is a valid medical reason to perform the test. A contraindication is a valid medical reason not to perform the test. For example, a basic cholesterol test may be indicated (medically appropriate) for a middle-aged person. However, if the same test was performed on that person very recently, then the existence of the previous test is a contraindication for the test (a medically valid reason to not perform it).

Information bias is the cognitive bias that causes healthcare providers to order tests that produce information that they do not realistically expect or intend to use for the purpose of making a medical decision. Medical tests are indicated when the information they produce will be used. For example, a screening mammogram is not indicated (not medically appropriate) for a woman who is dying, because even if breast cancer is found, she will die before any cancer treatment could begin.

In a simplified fashion, how much a test is indicated for an individual depends largely on its net benefit for that individual. Tests are chosen when the expected benefit is greater than the expected harm. The net benefit may roughly be estimated by:

, where:

- bn is the net benefit of performing a test

- Λp is the absolute difference between pre- and posttest probability of conditions (such as diseases) that the test is expected to achieve. A major factor for such an absolute difference is the power of the test itself, such as can be described in terms of, for example, sensitivity and specificity or likelihood ratio. Another factor is the pre-test probability, with a lower pre-test probability resulting in a lower absolute difference, with the consequence that even very powerful tests achieve a low absolute difference for very unlikely conditions in an individual (such as rare diseases in the absence of any other indicating sign), but on the other hand, that even tests with low power can make a great difference for highly suspected conditions. The probabilities in this sense may also need to be considered in context of conditions that are not primary targets of the test, such as profile-relative probabilities in a differential diagnostic procedure.

- ri is the rate of how much probability differences are expected to result in changes in interventions (such as a change from "no treatment" to "administration of low-dose medical treatment"). For example, if the only expected effect of a medical test is to make one disease more likely compared to another, but the two diseases have the same treatment (or neither can be treated), then, this factor is very low and the test is probably without value for the individual in this aspect.

- bi is the benefit of changes in interventions for the individual

- hi is the harm of changes in interventions for the individual, such as side effects of medical treatment

- ht is the harm caused by the test itself.

Some additional factors that influence a decision whether a medical test should be performed or not included: cost of the test, availability of additional tests, potential interference with subsequent test (such as an abdominal palpation potentially inducing intestinal activity whose sounds interfere with a subsequent abdominal auscultation), time taken for the test or other practical or administrative aspects. The possible benefits of a diagnostic test may also be weighed against the costs of unnecessary tests and resulting unnecessary follow-up and possibly even unnecessary treatment of incidental findings.[16]

In some cases, tests being performed are expected to have no benefit for the individual being tested. Instead, the results may be useful for the establishment of statistics in order to improve health care for other individuals. Patients may give informed consent to undergo medical tests that will benefit other people.

Patient expectations

In addition to considerations of the nature of medical testing noted above, other realities can lead to misconceptions and unjustified expectations among patients. These include: Different labs have different normal reference ranges; slightly different values will result from repeating a test; "normal" is defined by a spectrum along a bell curve resulting from the testing of a population, not by "rational, science-based, physiological principles"; sometimes tests are used in the hope of turning something up to give the doctor a clue as to the nature of a given condition; and imaging tests are subject to fallible human interpretation and can show "incidentalomas", most of which "are benign, will never cause symptoms, and do not require further evaluation," although clinicians are developing guidelines for deciding when to pursue diagnoses of incidentalomas.[17]

Standard for the reporting and assessment

The QUADAS-2 revision is available.[18]

See also

- Blood culture

- Chemical test

- Gold standard (test)

- Medical sign

- Molecular diagnostics

- Nailbed assessment

- Test panel

- Point-of-care testing

- EU IVD Regulation

References

- Al-Gwaiz LA, Babay HH (2007). "The diagnostic value of absolute neutrophil count, band count and morphological changes of neutrophils in predicting bacterial infections". Med Princ Pract. 16 (5): 344–347. doi:10.1159/000104806. PMID 17709921.

- Harvard.edu Archived 2014-12-23 at the Wayback Machine

Guide to Diagnostic Tests from Harvard Health - "Harvard.edu". Archived from the original on 2017-06-18. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- Ratcliffe JM, Halperin WE, Frazier TM, Sundin DS, Delaney L, Hornung RW (1986). "The prevalence of screening: a report from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and the Health National Occupational Hazard Survey". Journal of Occupational Medicine. 28 (10): 906–912. doi:10.1097/00043764-198610000-00003. PMID 3021937. Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- Osha.gov Archived 2020-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

US Dept. of Labor - Occupational Safety and Health Admin. - Murthy LI, Halperin WE (1995). "Medical Screening and Biological Monitoring: A guide to the literature for physicians". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 37 (2): 170–184. doi:10.1097/00043764-199502000-00016. PMID 7655958. S2CID 24916505. Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- Moltz KC, Postellon DC (1994). "Congenital hypothyroidism and mental development". Comprehensive Therapy. 20 (6): 342–346. PMID 8062543.

- OSA | Design of a high-sensor count fibre optic manometry catheter for in-vivo colonic diagnostics

- "Directive 98/79/CE on in vitro diagnostic medical devices". Archived from the original on 2021-10-21. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

- "In Vitro Diagnostic (IVD) tests". European Diagnostic Manufacturers Association. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009.

- "Glucose Tests". Lab Tests Online UK. 14 November 2019. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Liver Function Tests". Lab Tests Online UK. 10 January 2020. Archived from the original on 5 December 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Electrolytes and Anion Gap". Lab Tests Online UK. 9 October 2019. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Mediastinoscopy". Harvard Health. Harvard.edu. October 2016. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- Diagnostic Tests > Pap Smear, Harvard University, archived from the original on June 8, 2007

- Jarvik J, Hollingworth W, Martin B, Emerson S, Gray D, Overman S, Robinson D, Staiger T, Wessbecher F, Sullivan S, Kreuter W, Deyo R (2003). "Rapid magnetic resonance imaging vs radiographs for patients with low back pain: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 289 (21): 2810–8. doi:10.1001/jama.289.21.2810. PMID 12783911.

- Hall, Harriet (2019). "Too Many Medical Tests". Skeptical Inquirer. 43 (3): 25–27.

- Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM, et al. (QUADAS-2 Group) (October 2011). "QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies". Annals of Internal Medicine. 155 (8): 529–36. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. PMID 22007046.

Further reading

- World Health Organization (2019). First WHO Model List of Essential In Vitro Diagnostics. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/311567. ISBN 978-92-4-121026-3. ISSN 0512-3054. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 1017. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.