Postcard

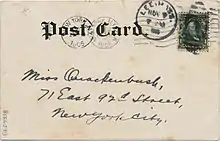

A postcard or post card is a piece of thick paper and/or thin cardboard, typically rectangular, intended for writing and mailing without an envelope. Non-rectangular shapes may also be used but are rare. There are novelty exceptions, such as wooden postcards, copper postcards sold in the Copper Country of the U.S. state of Michigan, and coconut "postcards" from tropical islands.

In some places, one can send a postcard for a lower fee than a letter. Stamp collectors distinguish between postcards (which require a postage stamp) and postal cards (which have the postage pre-printed on them). While a postcard is usually printed and sold by a private company, individual or organization, a postal card is issued by the relevant postal authority (often with pre-printed postage).[1]

Production of postcards blossomed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[2] As an easy and quick way for individuals to communicate, they became extremely popular.[2] The study and collecting of postcards is termed deltiology (from Greek deltion, small writing tablet, and English -logy, the study of).[1]

Historical Overview

1840 to 1864

Cards with messages have been sporadically created and posted by individuals since the beginning of postal services. The earliest known picture postcard was a hand-painted design on card created by the writer Theodore Hook. Hook posted the card, which bears a penny black stamp, to himself in 1840 from Fulham (part of London).[3][4] He probably did so as a practical joke on the postal service, since the image is a caricature of workers in the post office.[4][5] In 2002 the postcard sold for a record £31,750.[4]

In the United States, the custom of sending through the mail, at letter rate, a picture or blank card stock that held a message, began with a card postmarked in December 1848 containing printed advertising.[6] The first commercially produced card was created in 1861 by John P. Charlton of Philadelphia, who patented a private postal card, and sold the rights to Hymen Lipman, whose postcards, complete with a decorated border, were marketed as "Lipman's Postal Card".[1][2] These cards had no images. While the United States government allowed privately printed cards as early as February 1861, they saw little use until 1870, when experiments were done on their commercial viability.[7][2]

First postals and private postcards (ca. 1865 to 1880)

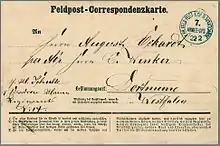

A Prussian postal official, Heinrich von Stephan, first proposed an "open post-sheet" made of stiff paper in 1865.[7][1][8] He proposed that one side would be reserved for a recipient address, and the other for a brief message.[8] His proposal was denied on grounds of being too radical and officials did not believe anyone would willingly give up their privacy.[8] In October 1869, the post office of Austria-Hungary accepted a similar proposal, also without images, and 3 million cards were mailed within the first three months.[1][8] With the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in July 1870, the government of the North German Confederation decided to take the advice of Austrian Emanuel Herrmann and issued postals for soldiers to inexpensively send home from the field.[7][1]

The period from 1870 to 1874 saw a great number of countries begin the issuance of postals. In 1870, the North German Confederation was joined by Baden, Bavaria, Great Britain, Luxembourg and Switzerland.[7][9] The year 1871 saw Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden introduce their own postals.[7][9] Algeria, Chile, France and Russia did so in 1872, and were followed by France, Japan, Romania, Serbia, Spain and the United States between 1873 and 1874.[9][7] Many of these postals included small images on the same side as the postage.[7] Postcards began to be sent internationally after the first Congress of the General Postal Union, which met in Bern, Switzerland in October 1874.[9][10] The Treaty of Bern was ratified in the United States in 1875.[10]

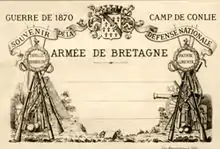

The first known printed picture postcard, with an image on one side, was created in France in 1870 at Camp Conlie by Léon Besnardeau (1829–1914). Conlie was a training camp for soldiers in the Franco-Prussian War. The cards had a lithographed design printed on them containing emblematic images of piles of armaments on either side of a scroll topped by the arms of the Duchy of Brittany and the inscription "War of 1870. Camp Conlie. Souvenir of the National Defence. Army of Brittany" (in French).[11] While these are certainly the first known picture postcards, there was no space for stamps and no evidence that they were ever posted without envelopes.[12]

In Germany, the bookdealer August Schwartz from Oldenburg is regarded as the inventor of the illustrated postcard. On July 16, 1870, he mailed a post correspondence card with an image of a man with a cannon, signaling the looming Franco-Prussian war.[13][14]

In the following year the first known picture postcard in which the image functioned as a souvenir was sent from Vienna.[15] The first advertising card appeared in 1872 in Great Britain and the first German card appeared in 1874. Private advertising cards started appearing in the United States around 1873, and qualified for a special postage rate of one cent.[7] Private cards inspired Lipman's card were also produced concurrently with the U.S. government postal in 1873.[7][1] The backs of these private cards contained the words "Correspondence Card", "Mail Card" or "Souvenir Card" and required two-cent postage if they were written upon.[7][2]

Golden age of postcards (ca. 1890 to 1915)

Cards showing images increased in number during the 1880s. Images of the newly built Eiffel Tower in 1889 and 1890 gave impetus to the postcard, leading to the so-called "golden age" of the picture postcard.[7] This golden age began slightly earlier in Europe than the United States, likely due to a depression in the 1890s.[7] Still, the Chicago World's Fair in 1893 excited many attendees with its line of "Official Souvenir" postals, which popularized the idea of picture postcards.[1][16] The stage was now set for private postcard industry to boom, which it did once the United States government changed the postage rate for private cards from two cents to one in May 1898.[1][16]

Spanning from approximately 1905 to 1915 in the United States, the golden age of postcards stemmed from a combination of social, economic, and governmental factors.[1][16] Demand for postcards increased, government restrictions on production loosened, and technological advances (in photography, printing, and mass production) made the boom possible.[1] In addition, the expansion of Rural Free Delivery allowed mail to be delivered to more American households than ever before.[1] Billions of postcards were mailed during the golden age, including nearly a billion per year in United States from 1905 to 1915, and 7 billion worldwide in 1905.[17][18] Many postcards from this era were in fact never posted but directly acquired by collectors themselves.[19]

Despite years of incredible success, economic and government forces would ultimately spell the end of the golden age. The peak came sometime between 1907 and 1910 for the United States.[1][2] In 1909, American publishers successfully lobbied to place tariffs on high quality German imports with the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act.[1] The effects of tariffs really started to make a large impact, and escalating hostilities in Europe made it difficult to import cards and ink into the United States.[1] The fad may have also simply run its natural course.[1] The war disrupted production efforts in Europe, although postcard production did not entirely stop.[20] Cards were still useful for propaganda, and for boosting troop morale.[17][20][21]

Post-World War I (1918 to present)

.jpg.webp)

After the war, the production of postcards continued, albeit in different styles than before. Demand for postcards decreased, especially as telephone usage grew.[1] There was still a need for postcards, which would be dubbed the "poor man's telephone".[22] As tastes changed, publishers began focusing on scenic views, humor, and fashion.[20] "White border" cards, which existed prior to the war, were produced in greater numbers from roughly 1915 to 1930 in the United States.[1][2] They required less ink and had lower production standards than fine German cards.[20] These were later replaced by "linen" postcards in the 1930s and 1940s, which used a printing process popularized by Curt Teich.[1][2] Finally, the modern era of Photochrom (often shortened simply to "chrome") postcards began in 1939, and gained momentum around 1950.[2] These glossy, colorful postcards are what we most commonly encounter today.[2] Postcard sales dropped to around 25% of 1990s levels,[23] with the growing popularity of social media around 2007, resulting in closure of long-established printers such as J Salmon Ltd in 2017.[24]

Country specifics

India

In July 1879, the Post Office of India introduced a quarter anna postcard that could be posted from one place to another within British India. This was the cheapest form of post provided to the Indian people to date and proved a huge success. The establishment of a large postal system spanning India resulted in unprecedented postal access: a message on a postcard could be sent from one part of the country to another part (often to a physical address without a nearby post office) without additional postage affixed. This was followed in April 1880 by postcards meant specifically for government use and by reply postcards in 1890.[25]: 423–424 The postcard facility continues to this date in independent India.

Japan

Official postcards were introduced in December 1873, shortly after stamps were introduced to Japan.[26][27] Return postcards were introduced in 1885, sealed postcards in 1900, and private postcards were allowed from 1900.[26]

In Japan, official postcards have one side dedicated exclusively to the address, and the other side for the content, though commemorative picture postcards and private picture postcards also exist. In Japan today, two particular idiosyncratic postcard customs exist: New Year's Day postcards (年賀状, nengajō) and return postcards (往復はがき, ōfuku-hagaki). New Year's Day postcards serve as greeting cards, similar to Western Christmas cards, while return postcards function similarly to a self-addressed stamped envelope, allowing one to receive a reply without burdening the addressee with postage fees. Return postcards consist of a single double-size sheet, and cost double the price of a usual postcard – one addresses and writes one half as a usual postcard, writes one's own address on the return card, leaving the other side blank for the reply, then folds and sends. Return postcards are most frequently encountered by non-Japanese in the context of making reservations at certain locations that only accept reservations by return postcard, notably at Saihō-ji (moss temple). For overseas purposes, an international reply coupon is used instead.

Russia

In the State Standard of the Russian Federation "GOST 51507-99. Postal cards. Technical requirements. Methods of Control" (2000)[28] gives the following definition:

Post Card is a standard rectangular form of a paper for public postings. According to the same state standards, cards are classified according to the type and kind.

Depending on whether or not the image on the card printing postage stamp cards are divided into two types:

- marked;

- unmarked.

Depending on whether or not the card illustrations, cards are divided into two types:

- illustrated;

- simple, that is non-illustrated.

Cards, depending on the location of illustrations divided into:

- Vector card at the location on the front side;

- on the reverse side.

Depending on the walking area cards subdivided into:

- cards for shipment within the Russian Federation (internal post);

- cards for shipment outside of the Russian Federation (international postage).

History

In Britain, postcards without images were issued by the Post Office in 1870, and were printed with a stamp as part of the design, which was included in the price of purchase. These cards came in two sizes. The larger size was found to be slightly too large for ease of handling, and was soon withdrawn in favour of cards 13mm (1⁄2 inch) shorter.[29] 75 million of these cards were sent within Britain during 1870.[8]

In 1973 the British Post Office introduced a new type of card, PHQ Cards, popular with collectors, especially when they have the appropriate stamp affixed and a first day of issue postmark obtained.

Seaside postcards

In 1894, British publishers were given permission by the Royal Mail to manufacture and distribute picture postcards, which could be sent through the post. It was originally thought that the first UK postcards were produced by printing firm Stewarts of Edinburgh but later research, published in Picture Postcard Monthly in 1991, has shown that the first UK picture card was published by ETW Dennis of Scarborough.[30] Two postmarked examples of the September 1894 ETW Dennis card have survived but no cards of Stewarts dated 1894 have been found.[31] Early postcards were pictures of landmarks, scenic views, photographs or drawings of celebrities and so on. With steam locomotives providing fast and affordable travel, the seaside became a popular tourist destination, and generated its own souvenir-industry.

In the early 1930s, cartoon-style saucy postcards became widespread, and at the peak of their popularity the sale of saucy postcards reached 16 million a year. They were often bawdy in nature, making use of innuendo and double entendres, and traditionally featured stereotypical characters such as vicars, large ladies, and put-upon husbands, in the same vein as the Carry On films.

In the early 1950s, the newly elected Conservative government were concerned at the apparent deterioration of morals in the UK and decided on a crackdown on these postcards. The main target of their campaign was the postcard artist Donald McGill. In the more liberal 1960s, the saucy postcard was revived and later came to be considered, by some, as an art form.[32]

Original postcards are now highly sought after, and rare examples can command high prices at auction. The best-known saucy seaside postcards were produced by the publishing company Bamforths of Holmfirth, West Yorkshire.

Despite the decline in popularity of postcards that are overtly "saucy", postcards continue to be a significant economic and cultural aspect of British seaside tourism. Sold by newsagents and street vendors, as well as by specialist souvenir shops, modern seaside postcards often feature multiple depictions of the resort in unusually favourable weather conditions. John Hinde used saturated colour and meticulously planned his photographs, which made his postcards of the later twentieth century become collected and admired as kitsch. Such cards are also respected as important documents of social history, and have been influential on the work of Martin Parr.

Postcard eras

.tif.jpg.webp)

There are several common motifs present in American postcard design, most shaped by production practices and laws in place at the time of production. These have been identified by deltiologists and grouped together into what are commonly referred to as eras or periods which describe a postcard's style or method of production. While features of these eras, such as a divided back, are present in other countries as well, the dates of production may differ. For example, "divided back" postcards were introduced to Great Britain in 1902, five years before the United States.[33] The golden age of postcards is commonly defined in the United States as starting around 1905, peaking between 1907 and 1910, and ending by World War I.[19][1][34] Listed here are eras of production for specific types of postcards, as typically defined by deltiologists. Most of the dates are not fixed dates, but approximate points in time as there was a lot of overlap in production.[2] These will be further elaborated upon in the following sections.

- Pioneer, 1870–1898[2]

- Alternate start dates include 1873 (first government postal issued)[35] and 1893 (World's Columbian Exposition)[36][37]

- Private Mailing Card‚ 1898–1901[2][36]

- Undivided Back‚ 1901–1907[2][35]

- Divided Back‚ 1907–1915[2][36][35]

- White Border‚ 1915–1930[2][36][35]

- Linen‚ 1930–1945[2][36][35]

- Photochrom(e)‚ 1939–present[2][36][35]

Others styles of postcards have fairly established dates of production as well. These are not typically referred to as eras, as they were never the predominant type at any given time.

Pioneer era

Under an act passed by the U.S. Congress on February 27, 1861, privately printed cards (which weighed one ounce or less) were allowed to be sent as mail.[2] John P. Charlton copyrighted the first postcard in America that same year.[2] The rights to this card were later sold to Hymen L. Lipman, who began reissuing the cards under his name in 1870.[2] The U.S. Postmaster General John Creswell recommended to the U.S. Congress one-cent postal cards in November 1870.[1] Legislation was passed on June 8, 1872, which allowed the government to produce postal cards.[2]

By law, only government-issued postcards were allowed to say "Postal Card".[2] Privately printed postcards were still allowed but they were more expensive to mail (two-cent postage versus one-cent for government cards).[2] Backs of these private cards typically contained the words "Correspondence Card", "Mail Card" or "Souvenir Card".[7][2] The Morgan Envelope Factory of Springfield, Massachusetts, claims to have produced the first American postcard in 1873.[50][51]

Political hold-ups including concerns by future President James Garfield (the Representative), delayed issuance of the official government postal.[1] Finally, it was issued in May 1873, and first went on sale in Springfield, Massachusetts on May 12 of that year.[1][2] According to The New York Times, postal clerks in the city sold 200,000 cards within 2.5 hours on May 14.[1] Nationwide, 31 million postal cards were sold by the end of June 1873, and more than 64 million by the end of September.[1] The numbers only continued to grow through 1910.[1]

World's fairs

There were many world's fairs and expositions held across the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The first to be depicted in an early advertising postcard was the Interstate Industrial Exposition that took place in Chicago in 1873.[52] As that exposition card was not intended to be a souvenir, the first postcard to be printed explicitly as a souvenir in the United States was created for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, also in Chicago.[52][16][9] There were 120 different images of the exposition printed on government postals by private distributors.[7] Among the most popular, was Charles W. Goldsmith's set of ten postcard designs (in full color) showing the exposition buildings.[7][53] Governmental postal cards, and private souvenir cards featuring buildings and exposition grounds remained popular staples of future expositions.[1][16]

One large mix-up occurred at the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta.[1] All of the postcards there were printed on plain card stock, so most people assumed they were government-issued postals requiring one cent for postage instead of two.[1] The incident made the headlines.[1]

Golden age of postcards

The U.S. Congress passed an act on May 19, 1898 which allowed private printers and publishers to officially produce postcards, and for them to be posted at the same rate as government-produced postals (one-cent, previously two).[2][54] Until this time, privately printed cards bore the terms "Correspondence Card", "Mail Card" or "Souvenir Card".[7][2] The act now required private cards to state "Private Mailing Card, Authorized by Act of Congress of May 19, 1898".[2] Hence, deltiologists have referred to this as the "Private Mailing Card Act".

This prohibition on verbiage was rescinded on December 24, 1901, by the Postmaster-General, who issued Post Office Order No. 1447.[2] It allowed private postcards to use the term "Post Card" on their backs.[2] The order also shortened the requirement and allowed private publishers to omit the citation to the 1898 act.[2] Still, correspondents could only write on the front of the postcard, the back was reserved for the recipient's address.[2] This has become known as the "undivided back" era of postcards.[2]

The Universal Postal Congress decreed that government-issued postcards in the United States could contain messages on the address side beginning March 1, 1907.[2] In line with these changes, the United States Congress passed an act on March 1, 1907, which extended this to privately produced cards.[2][52] These laws were further tweaked by orders of the U.S. Postmaster-General that same year.[2] This ushered in the "divided back" era of postcards, which lasted until World War I.[2] On these cards the back is divided into two sections: the left section is used for the message and the right for the address.[2]

Thus began the "golden age" of American postcards, which roughly spanned from 1905 to the First World War.[1] Others define the "Golden Age" as aligning more closely with the "divided back" era.[2] Regardless, it peaked between 1907 and 1910, and started to decline with the introduction of tariffs on German-printed postcards in 1909.[55][1][2][16] The postcard craze between 1907 and 1910 was particularly popular among rural and small-town women in Northern U.S. states.[34] Many social, economic, and governmental factors combined to create the postcard boom.[1] Demand for postcards increased, government restrictions on production loosened, and technological advances (in photography, printing, and mass production) made it possible.[1][16] In addition, the expansion of Rural Free Delivery allowed mail to be delivered to more American households than ever before.[1] Other factors included shifts in artistic taste among the public, and the development of a sale and distribution network of jobbers and importers—connecting Main Street America with German printers.[16] Billions of postcards were posted during the golden age, with nearly 700 million postcards mailed during the year ending June 30, 1908 alone.[16]

_postcard_to_Arthur_Oscar_Freudenberg_(1891-1968)_on_August_26%252C_1911.jpg.webp)

The decline began with the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909, which was mostly lobbied for by American publishers who did not wish to compete with German publishers.[16][1] By some estimates, the new tariffs on postcards were an increase of 300 percent.[56] Many distributors imported large quantities of German-produced cards before the tariffs took effect, causing a glut in the market.[55][16] German publishers began moving production to the United States shortly after the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act to keep selling to the American market.[57] Ultimately, the tariffs contributed to the end of the "golden age" as publishing quality decreased (American technology lagged behind German), and as public interest in collecting waned.[16][2] The National Postcard Association was formed to combat unfair practices, low prices, and an excessive amount of unsalable postcards.[16] Effects of the tariffs were reinforced by the British naval blockade of German merchant ships at the outbreak of World War I in 1914.[20] Postcard manufacturers called off their annual conventions that year, and many shifted to greeting card production.[16] The war cut off the importation of fine German-produced cards as well as dyes used for ink—which were largely produced by the German Empire.[20][58] Production of some postcards would continue during the war, to support propaganda efforts and troop morale.[20]

Post-World War I

In response to the war-time shortages of ink, and the restrictions placed on importation, American publishers began producing larger quantities of postcards which featured a white border on the edges.[20] Although these were seen occasionally prior to the war, this design change allowed publishers to save ink and lowered the precision threshold for cutting the cards.[20] The "white border" era would last from about 1913 to 1930.[20] During this period, public tastes had changed and publishers began focusing more on scenic views, humor, fashion, and surrealism.[20]

Mid-century "linen" postcards were produced in great quantity from 1930 to 1945, although they continued to be produced more than a decade after the introduction of Photochrom cards.[2] Despite the name, "linen" postcards were not produced on a linen fabric, but used newer printing processes that used an inexpensive card stock with a high rag content, and were then finished with a pattern which resembled linen.[2] The face of the cards is distinguished by a textured cloth appearance which makes them easily recognizable. The reverse of the card is smooth, like earlier postcards. The rag content in the card stock allowed a much more colorful and vibrant image to be printed than the earlier "white border" style. Due to the inexpensive production and bright realistic images they became popular.

One of the better known "linen-era" postcard manufacturers was Curt Teich and Company, who first produced the immensely popular "large letter linen" postcards (among many others). The card design featured a large letter spelling of a state or place with smaller photos inside the letters. The design can still be found in many places today. Other manufacturers include Tichnor and Company, Haynes, Stanley Piltz, E.C. Kropp, and the Asheville Postcard Company. Cards printed by Curt Teich and Company typically included production numbers in the stamp box, which can be used for dating.[59]

By the late 1920s new colorants had been developed that were very enticing to the printing industry. Though they were best used as dyes to show off their brightness, this proved to be problematic. Where traditional pigment based inks would lie on a paper's surface, these thinner watery dyes had a tendency to be absorbed into a paper's fibers, where it lost its advantage of higher color density, leaving behind a dull blurry finish. To experience the rich colors of dyes light must be able to pass through them to excite their electrons. A partial solution was to combine these dyes with petroleum distillates, leading to faster drying heatset inks. But it was Curt Teich who finally solved the problem by embossing paper with a linen texture before printing. The embossing created more surface area, which allowed the new heatset inks to dry even faster. The quicker drying time allowed these dyes to remain on the paper's surface, thus retaining their superior strength, which give Linens their telltale bright colors. In addition to printing with the usual CYMK colors, a lighter blue was sometimes used to give the images extra punch. Higher speed presses could also accommodate this method, leading to its widespread use. Although first introduced in 1931, their growing popularity was interrupted by the outbreak of war. They were not to be printed in numbers again until the later 1940s, when the war effort ceased consuming most of the country's resources. Even though the images on linen cards were based on photographs, they contained much handwork of the artists who brought them into production. There is of course nothing new in this; what it notable is that they were to be the last postcards to show any touch of the human hand on them. In their last days, many were published to look more like photo-based chrome cards that began to dominate the market. Textured papers for postcards had been manufactured ever since the turn of the century. But since this procedure was not then a necessary step in aiding card production, its added cost kept the process limited to a handful of publishers. Its original use most likely came from attempts to simulate the texture of canvas, thus relating the postcard to a painted work of fine art.[60]

World War II to present

The last and current postcard era, which began about 1939, is the "chrome" era, a shortened version of Photochrom (without the 'e' in American English; with in British English).[2] However these types of cards did not begin to dominate until about 1950 (partially due to war shortages during WWII).[2] The images on these cards are generally based on colored photographs, and are readily identified by the glossy appearance given by the paper's coating. "These still photographs made the invisible visible, the unnoticed noticed, the complex simple and the simple complex. The power of the still photograph forms symbolic structures and make the image a reality", as Elizabeth Edwards wrote in her book, The Tourist Image: Myths and Myth Making in Tourism.[61]

Standards

The United States Postal Service defines a postcard as: rectangular, at least 3+1⁄2 inches (88.9 mm) high × 5 inches (127 mm) long × 0.007 inches (0.178 mm) thick and no more than 4+1⁄4 inches (108 mm) high × 6 inches (152.4 mm) long × 0.016 inches (0.406 mm) thick.[62] However, some postcards have deviated from this (for example, shaped postcards).

Controversies

Legalities and censorship

The initial appearance of picture postcards (and the enthusiasm with which the new medium was embraced) raised some legal issues. Picture postcards allowed and encouraged many individuals to send images across national borders, and the legal availability of a postcard image in one country did not guarantee that the card would be considered "proper" in the destination country, or in the intermediate countries that the card would have to pass through. Some countries might refuse to handle postcards containing sexual references (in seaside postcards) or images of full or partial nudity (for instance, in images of classical statuary or paintings). For example, the United States Postal Service would only allow the delivery of postcards showing a back view of naked men from Britain if their posteriors were covered with a black bar.[63] Early postcards often showcased photography of nude women. Illegal to produce in the United States, these were commonly known as French postcards, due to the large number of them produced in France. Other countries objected to the inappropriate use of religious imagery. The Ottoman Empire banned the sale or importation of some materials relating to the Islamic prophet Muhammad in 1900. Affected postcards that were successfully sent through the Ottoman Empire before this date (and are postmarked accordingly) have a high rarity value and are considered valuable by collectors.

Lynchings

In 1873, the Comstock Act was passed in the United States, which banned the publication of "obscene matter as well as its circulation in the mails".[64] In 1908, §3893 was added to the Comstock Act, stating that the ban included material "tending to incite arson, murder, or assassination".[64] Although this act did not explicitly ban lynching photographs or postcards, it banned the explicit racist texts and poems inscribed on certain prints. According to some, these texts were deemed "more incriminating" and caused their removal from the mail instead of the photograph itself because the text made "too explicit what was always implicit in lynchings".[64] Some towns imposed "self-censorship" on lynching photographs, but section 3893 was the first step towards a national censorship.[64] Despite the amendment, the distribution of lynching photographs and postcards continued. Though they were not sold openly, the censorship was bypassed when people sent the material in envelopes or mail wrappers.[65]

World War I

Censorship played an important role in the First World War.[66] Each country involved utilized some form of censorship. This was a way to sustain an atmosphere of ignorance and give propaganda a chance to succeed.[66] In response to the war, the United States Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917 and Sedition Act of 1918. These gave broad powers to the government to censor the press through the use of fines, and later any criticism of the government, army, or sale of war bonds.[66] The Espionage Act laid the groundwork for the establishment of a Central Censorship Board which oversaw censorship of communications including cable and mail.[66]

Postal control was eventually introduced in all of the armies, to find the disclosure of military secrets and test the morale of soldiers.[66] In Allied countries, civilians were also subjected to censorship.[66] French censorship was modest and more targeted compared to the sweeping efforts made by the British and Americans.[66] In Great Britain, all mail was sent to censorship offices in London or Liverpool.[66] The United States sent mail to several centralized post offices as directed by the Central Censorship Board.[66] American censors would only open mail related to Spain, Latin America or Asia—as their British allies were handling other countries.[66] In one week alone, the San Antonio post office processed more than 75,000 letters, of which they controlled 77 percent (and held 20 percent for the following week).[66]

Soldiers on the front developed strategies to circumvent censors.[67] Some would go on "home leave" and take messages with them to post from a remote location.[67] Those writing postcards in the field knew they were being censored, and deliberately held back controversial content and personal matters.[67] Those writing home had a few options including free, government-issued field postcards, cheap, picture postcards, and embroidered cards meant as keepsakes.[68] Unfortunately, censors often disapproved of picture postcards.[68] In one case, French censors reviewed 23,000 letters and destroyed only 156 (although 149 of those were illustrated postcards).[68] Censors in all warring countries also filtered out propaganda that disparaged the enemy or approved of atrocities.[66] For example, German censors prevented postcards with hostile slogans such as "Jeder Stoß ein Franzos" ("Every hit a Frenchman") among others.[66]

Historical value

Postcards document the natural landscape as well as the built environment—buildings, gardens, parks, cemeteries, and tourist sites. They provide snapshots of societies at a time when few newspapers carried images.[16] Postcards provided a way for the general public to keep in touch with their friends and family, and required little writing.[16] Anytime there was a major event, a postcard photographer was there to document it (including celebrations, disasters, political movements, and even wars).[16] Commemorating popular humor, entertainment, fashion, and many other aspects of daily life, they also shed light on transportation, sports, work, religion, and advertising.[16] Cards were sent to convey news of death and birth, store purchases, and employment.[16]

As a primary source, postcards are incredibly important to the types of historical research conducted by historians, historic preservationists, and genealogists alike. They give insight into both the physical world, and the social world of the time. During their heyday postcards revolutionized communication, similar to social media of today.[8] For those studying communication, they highlight the adoption of media, its adaptation, and its ultimate discarding.[8] Postcards have been used to study topics as diverse as theatre, racial attitudes, and war.[69][18][70]

Digital collections

Libraries, archives, and museums have extensive collections of picture postcards; many of the postcards in these collections are digitized[71] Efforts are continuously being made by professionals in these fields to digitize these materials to make them more widely accessible to the public. For those interested, there are already several large collections viewable online. Some large digital collections of postcards include:

- OldNYC (New York Public Library)

- Digital Collections (New York Public Library)

- These collections include the Detroit Publishing Company, holiday postcards, WWI postcards, and more.

- Curt Teich Postcard Archives Digital Collection (Newberry Library)

- The Pendergast Years (Kansas City Public Library)

- Northwest Historical Postcards Collection (University of Idaho)

- Kansas City, Kansas Postcard Collection (Kansas City, Kansas Public Library)

- Ernest G. Best postcard collection of merchant vessels, naval vessels and sailing vessels, 1900–1940. State Library of New South Wales, PXE 722/Items 1–4961.

Collecting

It is likely that postcard collecting first began as soon as postcards were mailed. One could argue that actual collecting began with the acquisition of souvenir postcards from the world's fairs, which were produced specifically with the collector (souvenir hunter) in mind.[16] Later, during the golden age of postcards, collecting became a mainstream craze.[16] The frenzy of purchasing, mailing, and collecting postcards was often referred to as "postcarditis", with up to half purchased by collectors.[72][19] Clubs such as The Jolly Jokers, The Society for the Promulgation of Post Cards, and the Post Card Union sprang up to facilitate postcard exchanges, each having thousands of members.[17] Postcard albums were commonly seen in Victorian parlors, and had a place of prominence in many middle and upper class households.[16]

Today, postcard collecting is still a popular and widespread hobby. The value of a postcard is mainly determined by the image illustrated on it. Other important factors for collectors can be countries, issuers, and authors. Online catalogs can be found on collector websites and clubs.[73] These catalogs provide detailed information about each postcard alongside their picture. In addition, these websites include collection management tools, trading platforms, and forums to assist with discussions between collectors. The oldest continuously run club in the United States is the Metropolitan Postcard Club of New York City, founded in 1946.[74]

Glossary of terminology

Most of the terms on this list were devised by modern collectors to describe cards in their possession. For the most part, these terms were not used contemporaneously by publishers or others in the industry.

- 3D Postcard

- Postcards with artwork that appears in 3D. This can be done with different techniques, such as lenticular printing or hologram.

- Advertising Postcard

- Specialist marketing companies in many countries produce and distribute advertising postcards which are available for free. These are normally offered on wire rack displays in plazas, coffee shops and other commercial locations, usually not intended to be mailed.

- Appliqué

- A postcard that has some form of cloth, metal or other embellishment attached to it.

- Art Déco

- Artistic style of the 1920s, recognizable by its symmetrical designs and straight lines.

- Art Nouveau

- Artistic style of the turn of the century, characterized by flowing lines and flowery symbols, yet often depicting impressionist more than representational art.

- Artist Signed

- Postcards with artwork that has the artist's signature, and the art is often unique for postcards.

- Bas Relief

- Postcards with a heavily raised surface, giving a papier-mâché appearance.

- Big Letter

- A postcard that shows the name of a place in very big letters that do not have pictures inside each letter (see also Large Letter).

- Composites

- A number of individual cards, that when placed together in a group, form a larger picture. Also called "installment" cards.

- Court Card

- The official size for British postcards between 1894–1899, measuring 115 mm × 89 mm (4.5 in × 3.5 in).

- Divided Back

- Postcards with a back divided into two sections, one for the message, the other for the address. British cards were first divided in 1902 and American cards in 1907.[33]

- Early

- Any card issued before the divided back was introduced (pre-1907).

- Embossed

- Postcards with a raised surface.

Exaggeration

Postcards featuring impossibly large animals and crops, created using trick photography and other methods.

- Folded

- Postcards that are folded, so that they have at least 4 pages. Most folded cards need to be mailed inside an envelope, but there are some that can be mailed directly.

- Hand-tinted

- Black-and-white images were tinted by hand using watercolors and stencils.

- Hold-to-Light

- Also referred to as 'HTL', postcards often of a night time scene with cut out areas to show the light.

- Intermediate Size

- The link between Court Cards and Standard Size, measuring 130 mm × 80 mm (5.1 in × 3.1 in).

- Kaleidoscope

- Postcards with a rotating wheel that reveals a myriad of colours and patterns when turned.

.jpg.webp)

- Large Letter

- A postcard that has the name of a place shown as a series of very large letters, inside of each of which is a picture of that locale (see also Big Letter).

- Maximum Card

- Postcards with a postage stamp placed on the picture side of the card and tied by the cancellation, usually the first day of issue.

- Midget Postcard

- Novelty cards of the size 90 mm × 70 mm (3.54 in × 2.76 in).

- Novelty

- Any postcard that deviates from the norm. These include cards which do something (such as mechanical postcards) or which have articles attached to them.[75] They could also be printed in an unusual size or shape, or made of strange materials (including leather, wood, metal, silk, or coconut).[75]

- Oilette

- A trade name used by Raphael Tuck & Sons for postcards reproduced from original painting.

- Postcard Folder

- A set of picture postcards, printed on light-weight paper, which fold out accordion-style from an outer envelope (folder). These typically contain more than 5 cards.

- Postcardese

- The style of writing used on postcards; short sentences, jumping from one subject to another.

- QSL Card

- Postcards that confirms a successful reception of a radio signal on amateur radio.

- Real Photographic

- "Real photo postcards", as collectors have dubbed them, are often abbreviated as "RP" or "RPPC". Most of these were produced in small batches from an original negative by an individual or a local store.[37] They are not printed.

- Reward Card

- Cards that were given away to school children for good work.

- Special Property Card

- Postcards that are made of a material other than cardboard or contains something made not of cardboard.

- Standard Size

- Introduced in Britain in November 1899, measuring 140 mm × 89 mm (5.5 in × 3.5 in).

- Topographical

- Postcards showing street scenes and general views. Judges Postcards produced many British topographical views.

- Undivided Back

- Postcards with a plain back where all of this space was used for the address. This is usually in reference to early cards, although undivided were still in common use up until 1907.

- Vignette

- Usually found on "undivided back" cards, consisting of a design that does not occupy the whole of the picture side. Vignettes may be anything from a small sketch in one corner of the card, to a design cover three quarters of the card. The purpose is to leave some space for the message to be written, as the entire reverse of the card could only be used for the address.

- Write-Away

- A card with the opening line of a sentence, which the sender would then complete. Often found on early comic cards.

Gallery

Entry of the Great Mosque of Kairouan, postcard from 1900

Entry of the Great Mosque of Kairouan, postcard from 1900 Fortress in Vyborg, postcard from 1917

Fortress in Vyborg, postcard from 1917

Hawaiian Aloha nui Postcard c. 1908

Hawaiian Aloha nui Postcard c. 1908 German postcard with inscription "This beer belongs to my master!"

German postcard with inscription "This beer belongs to my master!" Gruss aus-type postcard, published by the Munich based German printing house Purger & Co.

Gruss aus-type postcard, published by the Munich based German printing house Purger & Co.

See also

- Advertising postcard

- Frances Brundage

- Ellen Clapsaddle

- Deltiology

- e-card

- Francis Frith

- Greeting card

- Esther Howland

- Illustrated stamped envelope

- Judges Postcards

- Mail Art

- Paper sizes

- PHQ Cards

- Postal card

- Postcardware

- Postcrossing

- Postino

- PostSecret

- QSL card

- Real photo postcard

- F. G. O. Stuart

- James Valentine

- Comité des Étudiants Américains de l'École des Beaux-Arts Paris

References

- United States Postal Service (September 2014). "Stamped Cards and Postcards" (PDF). United States Postal Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-08-26. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- "Postcard History | Smithsonian Institution Archives". 2018-11-23. Archived from the original on 2018-11-23. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- "Oldest picture postcard". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Oldest postcard sells for £31,750". BBC News. 2002-03-08. Retrieved 2012-06-16.

- Arifa Akbar, "Oldest picture postcard in the world snapped up for £31,750", The Independent, 9 March 2002.

- "Pre History of the Postcard 1848–1872". Metropolitan Postcard Club of New York City.

- Petrulis, Alan. "MetroPostcard History of Postcards 1873–1897". www.metropostcard.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- Cure, Monica (2013-06-22). "Tweeting by mail: The postcard's stormy birth". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- "Chicago Postcard Museum – How to Age a Postcard". www.chicagopostcardmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- "Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America 1776–1949 Compiled under the direction of Charles I. Bevans LL.B." avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- The New York Times, September 21, 1904.

- "Histoire de la Carte Postale, Cartopole, Baud" (in French). Cartolis.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2012-06-16.

- Dagmar Breitenbach: Instagram, 19th-century style: The first German postcard In: Deutsche Welle, July 16, 2020, Retrieved 2021-02-07.

- Helmfried Luers: The First Picture Postcard In: The Postcard Album #21, Retrieved 2021-02-07.

- Frank Staff, The Picture Postcard & Its Origins, New York: F.A. Praeger, p.51.

- Bassett, Fred (2018-12-13). "Postcard Collection – Essay, Appendix C: New York State Library". Archived from the original on 2018-12-13. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- Petrulis, Alan. "The Peak and Decline of the Golden Age 1907–1913". www.metropostcard.com.

- Baldwin, Brooke (1988). "On the Verso: Postcard Messages as a Key to Popular Prejudices". Journal of Popular Culture. 22 (3): 15–28. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1988.2203_15.x.

- Petrulis, Alan. "MetroPostcard History of Postcards". www.metropostcard.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- Petrulis, Alan. "MetroPostcard History of Postcards 1914–1945". www.metropostcard.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- Frank Jacob and Mark D. Van Ells, A Postcard View of Hell: One Doughboy's Souvenir Album of the First World War. Wilmington, DE: Vernon Press, 2019.

- Gendreau, Bianca: Putting Pen to Paper, Special Delivery: Canada's Postal Heritage, ed. Francine Brousseau, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Fredericton 2000, pp. 27–29

- Settembre, Jeanette (30 Sep 2017). "Postcards are becoming extinct and 5 other industries millennials are killing". MarketWatch. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Postcards on the edge as Britain's oldest publishers signs off". The Guardian. 2017-09-25. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- The Imperial Gazetteer of India. (1908). Vol 3 (Economic), p. 424

- "PostcardGuide Japan/Konnichiwa!". www.photojpn.org.

- PostcardGuide Japan, April 2, 1997

- "ГОСТ Р 51507-99 – НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЕ СТАНДАРТЫ". protect.gost.ru.

- Willoughby, Martin (1992). A History of Postcards. London England: Bracken Books. p. 160. ISBN 1858911621.

- Sept and Dec 1991 Picture Postcard Monthly

- PPC Annual 2015

- Nick Collins (5 August 2010). "Bawdy seaside postcards on display". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- Petrulis, Alan. "Post Card undivided". www.metropostcard.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- Gifford, Daniel (2013) American Holiday Postcards 1905–1915: Imagery and Context. McFarland Press. ISBN 0786478179.

- "Chicago Postcard Museum – Postcard Era History". www.chicagopostcardmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- Ellison, Todd (2006-08-07). "Tips for determining when a U.S. postcard was published". www.fortlewis.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- Palmer, Richard. "Postcard Craze Engulfs the Great Lakes". Inland Seas. 50 (1): 39–45.

- "Leather Postcards". Flickr. 25 March 2017. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

Sending and receiving postcards between 1907 and 1915 were the equivalent to the text-messaging communication phenomenon of today. A particular genre from the early 1900 to 1909 was the novelty postcard produced on leather, more commonly referred to as leather postcards. Although leather postcards became quite popular, they were banned for postal use by the United States Postal Service in 1909. Thus, leather postcards postmarked after 1909 tend to be very rare – though not unseen.

- Aizenberg, Salo (2013). Hatemail: Anti-Semitism on Picture Postcards. The Jewish Publication Society. p. 121. ISBN 978-0827609495.

Leather postcards were novelty items popular in the United States from around 1900 to 1909, when they were banned by the post office due to the difficulty of processing the leather in sorting machines. Leather postcards were produced both by commercial publishers and by individuals who purchased the raw leather and used burning kits to create the image.

- Tribune-Herald, Terri Jo Ryan Special to the. "Brazos Past: Leather postcards from early 20th century present unique slices of life". WacoTrib.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

These leather postcards were a fad from about 1900 until 1909, when they were banned by the U.S. Postal Service because of the damage they inflicted on sorting machinery.

- "Short-lived frenzy over leather postcards – Auction Finds". 8 August 2016. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- "[Untitled]". The Goldfield News (Goldfield, Nevada). 1904-07-29. p. 1.

J. W. Halterman received a burnt leather souvenir postal card from his wife Wednesday, on which was the picture of a bear chasing a man up a tree and the inscription, "no time to write from Colorado." He immediately took an ordinary postal, drew a picture of a man chasing a bear up a tree, wrote at the side "no time to write from Nevada" and sent it on to his wife.

- "[Untitled]". The Winfield Daily Free Press (Winfield, Kansas). 1904-09-27. p. 8.

"Doc" Johnson has honored the Free Press with a leather post card from Colorado.

- "[Untitled]". Tri-City Evening Star (Davenport, Iowa). 1904-10-01. p. 8.

Justice L. E. Roddewig this morning received a leather postal card from a Davenport friend visiting in Omaha. The card is certainly a novelty.

- "A Postal Card of Leather". Sterling Evening Gazette (Sterling, Illinois). 1904-10-12. p. 2.

Scott Williams has begun the making of a new article of pyrography which is sure to prove exceptionally popular. It is a lweather post card, to be used as a souvenir of Sterling, upon the back of which is a photograph of Sterling scenery or buildings and suitable inscriptions done with the red hot point. The card is attractive and there is no doubt that Mr. Williams will secure many orders.

- "[Untitled]". The Miami News (Miami, Florida). 1904-10-13. p. 5.

The Metropolis is in receipt of a pretty burnt leather souvenir post-card from Mr. E. F. Boss, of Petoskey, Mich., which is dated the 10th, and shows he and family "starting for Miami."

- "Leather Postal Card". Logansport Pharos Tribune (Logansport, Indiana). 1904-10-19. p. 8.

Dr. J. A. Little received a souvenir leather postal card from Dr. A. J. Herrmann who, with his wife and family are sojourning in California, this morning stating that he would be home Sunday. He writes that his wife and children have gained very much in flesh and that they are enjoying the trip immensely. The card was mailed at Los Angeles.

- "Valentine Day Near". Dixon Evening Telegraph (Dixon, Illinois). 1905-02-01. p. 5.

Pretty hearts of wood are prepared and decorated with beautiful Christy or Gibson heads on them. They can be sent through the mail with address on one side just like a post card. These with the leather post card will be very popular this year. There are also the heart shaped handkercief [sic] boxes with appropriate pictures burnt on them. All of these things can also be put in watercolors and this seems to be quite the thing now.

- "[Untitled]". Sterling Daily Standard (Sterling, Illinois). 1905-02-06. p. 8.

Scott Williams says that the leather post card valentines are making a great bit and that his orders for them have caused him to increase the output of them as rapidly as possible. Whole sheep skins are cut into post card size and then pictures burned on them with appropriate wording, or painted in water colors. The Bloomington agency is demanding large quantities and second orders have come from Champaign, Rockford, Dixon and Clinton, Ia. Four artists are at work steadily at the studio.

- "History & Innovation". Bostonhistorycollaborative.org. Retrieved 2012-06-16.

- "Springfield 375 | Springfield's Official 375th Anniversary Celebration Site". Springfield375.org. Archived from the original on 2012-04-05. Retrieved 2012-06-16.

- "The History of Postcards".

- Willoughby, Martin (1992). A History of Postcards. London England: Bracken Books. p. 42. ISBN 1858911621.

- "An Act To amend the postal laws relating to use of postal cards" (PDF). United States Congress Statutes at Large. 20: 358. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-02.

- "Post Card Situation". The American Stationer. 65: 26. 1910-04-23. hdl:2027/nyp.33433090917406.

- "Tariff Bill Comparisons". Geyer's Stationer. 48: 1 & 20. 1909-08-12. hdl:2027/nyp.33433108136940.

- "Post Card Situation: New High Tariff Causes Foreign Manufacturers To Make Plans For American Factories—German Firms Active". Geyer's Stationer. 48: 6. 1909-11-04. hdl:2027/nyp.33433108136940.

- "German Dyes Scarce". Geyer's Stationer. 58: 27. 1915-05-20. hdl:2027/nyp.33433108135934.

- "Guide to Dating Curt Teich Postcards" (PDF). Newberry Library. 2016.

- Linen Cards. Metropolitan Postcard Club of New York City.

- Edwards, Elizabeth (1996). The Tourist Image: Myths and Myth Making in Tourism. West Sussex PO19 1UD, England: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 199–200. ISBN 0-471-96309-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - "USPS – Mail Characteristics – Sizes for Cards". USPS. Archived from the original on 2008-01-20. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- "Naked film postcards returned to sender". BBC News. 30 July 2001. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- Kim, Linda (2012). "A Law of Unintended Consequences: United States Postal Censorship of Lynching Photographs". Visual Resources. Taylor & Francis. 28 (2): 171–193. doi:10.1080/01973762.2012.678812.

- Apel, Dora (2004). Imagery of Lynching: Black Men, White Women, and the Mob. New Brunswick, N.J.; London: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3459-6.

- Demm, Eberhard. "Censorship | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)". International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Archived from the original on 2020-01-20. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- "Circumventing the censorship and "self-censorship"". The World of the Habsburgs. Archived from the original on 2018-12-21. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- Hanna, Martha (2014-10-08). "War Letters: Communication between Front and Home Front | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)". International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Archived from the original on 2019-03-26. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- Farfan, P. (2012). ""The Picture Postcard is a sign of the times": Theatre Postcards and Modernism". Theatre History Studies. 32: 93–119. doi:10.1353/ths.2012.0018. S2CID 192002863.

- Vanderwood, Paul (1988). "Writing History with Picture Postcards". The Journal of San Diego History. 34 (1). Archived from the original on 2016-06-29.

- "Old Postcards: Messages about the Past". Primary Source Bazaar. 24 May 2019.

- "18 August 1906". The American Stationer. Vol. 60. Redman & Kerry. 1906. p. 8.

- "Postcards on Colnect". colnect.com. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- "Metropolitan Postcard Club of New York City". www.metropolitanpostcardclub.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- "Novelty leather postcards". Barr's Postcard News & Ephemera. 2016-11-21.

Novelty postcards include Hold-to-lights, Die-cuts, leather, silk or metal applied, printed on silk, burnt wood, mechanical and on and on. They are just about anything but the flat printed or real photo postcards. One category is postcards made of leather.

External links

- The Postcard Traders association—Represents professionals within the UK postcard industry.

- The International Federation of Postcard Dealers—Represents professional postcard dealers worldwide.

- Japanese Postcard Collecting Research きのう屋日本の絵葉書コレクション

- Bowden Postcard Collection Online. Approximately 24,000 digitized postcards, maintained by the Walter Havighurst Special Collections in the Miami University Libraries.

- abadie.co.uk, currently the only book of classic John Hinde postcards with the senders messages transcribed

- johnhindecollection.com, a website dedicated to John Hinde Postcards

- "Plowman Family Postcard Collection". University of St. Michael's College, John M. Kelly Library. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

The full text of A New Thing in Postage (report on the first cheap postcard used in Austria) at Wikisource

The full text of A New Thing in Postage (report on the first cheap postcard used in Austria) at Wikisource- PostcardTree. 30,000+ digitized and postally used postcards.

- Newberry Postcards at Internet Archive – digital collection of 26,000+ postcards

- National Trust Library Historic Postcard collection at the University of Maryland libraries

- Institute of American Deltiology Postcard collection at the University of Maryland libraries

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)