Rabies virus

Rabies virus, scientific name Rabies lyssavirus, is a neurotropic virus that causes rabies in humans and animals. Rabies transmission can occur through the saliva of animals and less commonly through contact with human saliva. Rabies lyssavirus, like many rhabdoviruses, has an extremely wide host range. In the wild it has been found infecting many mammalian species, while in the laboratory it has been found that birds can be infected, as well as cell cultures from mammals, birds, reptiles and insects.[2] Rabies is reported in more than 150 countries on all continents, with the exclusion of Antarctica.[3] The main burden of disease is reported in Asia and Africa, but some cases have been reported also in Europe in the past 10 years, especially in returning travellers.[4]

| Rabies lyssavirus | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

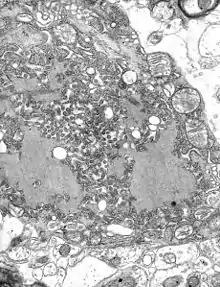

| Colorized transmission electron micrograph showing the rabies virus (in red) infecting cultured cells | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Monjiviricetes |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Rhabdoviridae |

| Genus: | Lyssavirus |

| Species: | Rabies lyssavirus |

| Member viruses | |

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Rabies lyssavirus has a cylindrical morphology and is a member of the Lyssavirus genus of the Rhabdoviridae family. These viruses are enveloped and have a single stranded RNA genome with negative-sense. The genetic information is packaged as a ribonucleoprotein complex in which RNA is tightly bound by the viral nucleoprotein. The RNA genome of the virus encodes five genes whose order is highly conserved. These genes code for nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), glycoprotein (G) and the viral RNA polymerase (L).[5] The complete genome sequences range from 11,615 to 11,966 nt in length.[6]

All transcription and replication events take place in the cytoplasm inside a specialized “virus factory”, the Negri body (named after Adelchi Negri[7]). These are 2–10 µm in diameter and are typical for a rabies infection and thus have been used as definite histological proof of such infection.[8]

Structure

Rhabdoviruses have helical symmetry, so their infectious particles are approximately cylindrical in shape. They are characterized by an extremely broad host spectrum ranging from plants to insects and mammals; human-infecting viruses more commonly have icosahedral symmetry and take shapes approximating regular polyhedra.

The rabies genome encodes five proteins: nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), glycoprotein (G) and polymerase (L). All rhabdoviruses have two major structural components: a helical ribonucleoprotein core (RNP) and a surrounding envelope. In the RNP, genomic RNA is tightly encased by the nucleoprotein. Two other viral proteins, the phosphoprotein and the large protein (L-protein or polymerase) are associated with the RNP. The glycoprotein forms approximately 400 trimeric spikes which are tightly arranged on the surface of the virus. The M protein is associated both with the envelope and the RNP and may be the central protein of rhabdovirus assembly.[9]

Rabies lyssavirus has a bullet-like shape with a length of about 180 nm and a cross-sectional diameter of about 75 nm. One end is rounded or conical and the other end is planar or concave. The lipoprotein envelope carries knob-like spikes composed of Glycoprotein G. Spikes do not cover the planar end of the virion (virus particle). Beneath the envelope is the membrane or matrix (M) protein layer which may be invaginated at the planar end. The core of the virion consists of helically arranged ribonucleoprotein.

Genome organization

The rhabdovirus virion is an enveloped, rod- or bullet-shaped structure containing five protein species. The nucleoprotein (N) coats the RNA at the rate of one monomer of protein to nine nucleotides, forming a nucleocapsid with helical symmetry. Associated with the nucleocapsid are copies of P (phosphoprotein) and L (large) protein. The L protein is well named, its gene taking up about half of the genome. Its large size is justified by the fact that it is a multifunctional protein. The M (matrix) protein forms a layer between the nucleocapsid and the envelope, and trimers of G (glycoprotein) form spikes that protrude from the envelope. The genomes of all rhabdoviruses encode these five proteins, and in the case of Rabies Lyssavirus they are all of them.[10]

| Symbol | Name | UniProt | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Nucleoprotein | P16285 | Coats the RNA. |

| P | Phosphoprotein | P16286 | L cofactor and various regulatory functions. Has many isoforms from multiple initiation. |

| M | Matrix | P16287 | Keeps nucleoprotein condensed. Important for assembly; has roles in regulation. |

| G | Glycoprotein | P16288 | Spike. Uses muscular nAChR, NCAM, and p75NTR as receptors. |

| L | Large structural protein | P16289 | RNA replicase of the Mononegavirales type. |

Life cycle

After receptor binding, Rabies lyssavirus enters its host cells through the endosomal transport pathway. Inside the endosome, the low pH value induces the membrane fusion process, thus enabling the viral genome to reach the cytosol. Both processes, receptor binding and membrane fusion, are catalyzed by the glycoprotein G which plays a critical role in pathogenesis (mutant virus without G proteins cannot propagate).[5]

The next step after its entry is the transcription of the viral genome by the P-L polymerase (P is an essential cofactor for the L polymerase) in order to make new viral protein. The viral polymerase can only recognize ribonucleoprotein and cannot use free RNA as template. Transcription is regulated by cis-acting sequences on the virus genome and by protein M which is not only essential for virus budding but also regulates the fraction of mRNA production to replication. Later in infection, the activity of the polymerase switches to replication in order to produce full-length positive-strand RNA copies. These complementary RNAs are used as templates to make new negative-strand RNA genomes. They are packaged together with protein N to form ribonucleoprotein which then can form new viruses.[8]

Infection

In September 1931, Joseph Lennox Pawan of Trinidad found Negri bodies in the brain of a bat with unusual habits. In 1932, Pawan first discovered that infected vampire bats could transmit rabies to humans and other animals.[11][12][13]

From the wound of entry, Rabies lyssavirus travels quickly along the neural pathways of the peripheral nervous system. The retrograde axonal transport of Rabies lyssavirus to the central nervous system (CNS) is the key step of pathogenesis during natural infection. The exact molecular mechanism of this transport is unknown although binding of the P protein from Rabies lyssavirus to the dynein light chain protein DYNLL1 has been shown.[14] P also acts as an interferon antagonist, thus decreasing the immune response of the host.

From the CNS, the virus further spreads to other organs. The salivary glands located in the tissues of the mouth and cheeks receive high concentrations of the virus, thus allowing it to be further transmitted due to projectile salivation. Fatality can occur from two days to five years from the time of initial infection.[15] This however depends largely on the species of animal acting as a reservoir. Most infected mammals die within weeks, while strains of a species such as the African yellow mongoose (Cynictis penicillata) might survive an infection asymptomatically for years.[16]

Signs and symptoms

The first symptoms of rabies may be very similar to those of the flu, including general weakness or discomfort, fever, or headache. These symptoms may last for days. There may be also discomfort or a prickling or itching sensation at the site of bite, progressing within days to symptoms of cerebral dysfunction, anxiety, confusion, agitation. As the disease progresses, the person may experience delirium, abnormal behavior, hallucinations, and insomnia. Rabies lyssavirus may also be inactive in its host's body and become active after a long period of time.[17]

Antigenicity

Upon viral entry into the body and also after vaccination, the body produces virus neutralizing antibodies which bind and inactivate the virus. Specific regions of the G protein have been shown to be most antigenic in leading to the production of virus neutralizing antibodies. These antigenic sites, or epitopes, are categorized into regions I–IV and minor site a. Previous work has demonstrated that antigenic sites II and III are most commonly targeted by natural neutralizing antibodies.[18] Additionally, a monoclonal antibody with neutralizing functionality has been demonstrated to target antigenic site I.[19] Other proteins, such as the nucleoprotein, have been shown to be unable to elicit production of virus neutralizing antibodies.[20] The epitopes which bind neutralizing antibodies are both linear and conformational.[21]

Evolution

All extant rabies viruses appear to have evolved within the last 1500 years.[22] There are seven genotypes of Rabies lyssavirus. In Eurasia cases are due to three of these—genotype 1 (classical rabies) and to a lesser extent genotypes 5 and 6 (European bat lyssaviruses type-1 and -2).[23] Genotype 1 evolved in Europe in the 17th century and spread to Asia, Africa and the Americas as a result of European exploration and colonization.

Bat rabies in North America appears to have been present since 1281 AD (95% confidence interval: 906–1577 AD).[24]

The rabies virus appears to have undergone an evolutionary shift in hosts from Chiroptera (bats) to a species of Carnivora (i.e. raccoon or skunk) as a result of an homologous recombination event that occurred hundreds of years ago.[25] This recombination event altered the gene that encodes the virus glycoprotein that is necessary for receptor recognition and binding.

Application

Rabies lyssavirus is used in research for viral neuronal tracing to establish synaptic connections and directionality of synaptic transmission.[26]

See also

- Cryptic bat rabies

- Rabies vaccine

- Duck embryo vaccine

- Arctic rabies virus

- Bat-borne virus

References

- Walker, Peter (15 June 2015). "mplementation of taxon-wide non-Latinized binomial species names in the family Rhabdoviridae" (PDF). International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Retrieved 11 February 2019.

Rabies virus Rabies lyssavirus rabies virus (RABV)[M13215]

- Carter, John; Saunders, Venetia (2007). Virology: Principles and Applications. Wiley. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-470-02386-0.

- "Rabies". www.who.int. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- Riccardi, Niccolò; Giacomelli, Andrea; Antonello, Roberta Maria; Gobbi, Federico; Angheben, Andrea (June 2021). "Rabies in Europe: An epidemiological and clinical update". European Journal of Internal Medicine. 88: 15–20. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2021.04.010. PMID 33934971.

- Finke S, Conzelmann KK (August 2005). "Replication strategies of rabies virus". Virus Res. 111 (2): 120–131. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2005.04.004. PMID 15885837.

- "Rabies complete genome". NCBI Nucleotide Database. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- synd/2491 at Who Named It?

- Albertini AA, Schoehn G, Weissenhorn W, Ruigrok RW (January 2008). "Structural aspects of rabies virus replication". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65 (2): 282–294. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7298-1. PMID 17938861. S2CID 9433653.

- CDC Rabies virus Structure 26 May 2016

- Carter & Saunders 2007, p. 177

- Pawan, J. L. (1936). "Transmission of the Paralytic Rabies in Trinidad of the Vampire Bat: Desmodus rotundus murinus Wagner, 1840". Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 30: 137–156. doi:10.1080/00034983.1936.11684921. ISSN 0003-4983.

- Pawan, J. L. (1936). "Rabies in the vampire bat of Trinidad, with special reference to the clinical course and the latency of infection". Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 30: 101–129. doi:10.1080/00034983.1936.11684921. ISSN 0003-4983.

- Waterman, James A. (1965). "The History of the Outbreak of Paralytic Rabies in Trinidad Transmitted by Bats to Human beings and Lower animals from 1925". Caribbean Medical Journal. 26 (1–4): 164–9. ISSN 0374-7042.

- Raux H, Flamand A, Blondel D (November 2000). "Interaction of the rabies virus P protein with the LC8 dynein light chain". J. Virol. 74 (21): 10212–6. doi:10.1128/JVI.74.21.10212-10216.2000. PMC 102061. PMID 11024151.

- "Rabies". University of Northern British Columbia. Archived from the original on 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- Taylor PJ (December 1993). "A systematic and population genetic approach to the rabies problem in the yellow mongoose (Cynictis penicillata)". Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 60 (4): 379–87. PMID 7777324.

- CDC. What are the signs and symptoms of rabies?. February 15, 2012. https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/symptoms/

- Benmansour A (1991). "Antigenicity of rabies virus glycoprotein". Journal of Virology. 65 (8): 4198–4203. doi:10.1128/JVI.65.8.4198-4203.1991. PMC 248855. PMID 1712859.

- Marissen, WE.; Kramer, RA.; Rice, A.; Weldon, WC.; Niezgoda, M.; Faber, M.; Slootstra, JW.; Meloen, RH.; et al. (Apr 2005). "Novel rabies virus-neutralizing epitope recognized by human monoclonal antibody: fine mapping and escape mutant analysis". J Virol. 79 (8): 4672–8. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.8.4672-4678.2005. PMC 1069557. PMID 15795253.

- Wiktor, TJ.; György, E.; Schlumberger, D.; Sokol, F.; Koprowski, H. (Jan 1973). "Antigenic properties of rabies virus components". J Immunol. 110 (1): 269–76. PMID 4568184.

- Bakker, AB.; Marissen, WE.; Kramer, RA.; Rice, AB.; Weldon, WC.; Niezgoda, M.; Hanlon, CA.; Thijsse, S.; et al. (Jul 2005). "Novel human monoclonal antibody combination effectively neutralizing natural rabies virus variants and individual in vitro escape mutants". J Virol. 79 (14): 9062–8. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.14.9062-9068.2005. PMC 1168753. PMID 15994800.

- Nadin-Davis, Susan A.; Real, Leslie A. (2011). "Molecular Phylogenetics of the Lyssaviruses—Insights from a Coalescent Approach". Advances in Virus Research. 79: 203–238. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-387040-7.00011-1. ISBN 9780123870407. PMID 21601049.

- McElhinney, L. M.; Marston, D. A.; Stankov, S; Tu, C.; Black, C.; Johnson, N.; Jiang, Y.; Tordo, N.; Müller, T.; Fooks, A. R. (2008). "Molecular epidemiology of lyssaviruses in Eurasia". Dev Biol (Basel). 131: 125–131. PMID 18634471.

- Kuzmina, N. A.; Kuzmin, I. V.; Ellison, J. A.; Taylor, S. T.; Bergman, D. L.; Dew, B.; Rupprecht, C. E. (2013). "A reassessment of the evolutionary timescale of bat rabies viruses based upon glycoprotein gene sequences". Virus Genes. 47 (2): 305–310. doi:10.1007/s11262-013-0952-9. PMC 7088765. PMID 238396.

- Ding NZ, Xu DS, Sun YY, He HB, He CQ. A permanent host shift of rabies virus from Chiroptera to Carnivora associated with recombination. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-016-0028-x.

- Ginger, M.; Haberl M.; Conzelmann K.-K.; Schwarz M.; Frick A. (2013). "Revealing the secrets of neuronal circuits with recombinant rabies virus technology". Front. Neural Circuits. 7: 2. doi:10.3389/fncir.2013.00002. PMC 3553424. PMID 23355811.