Rain (Beatles song)

"Rain" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles, released on 30 May 1966 as the B-side of their "Paperback Writer" single. Both songs were recorded during the sessions for Revolver, although neither appear on that album. "Rain" was written by John Lennon and credited to the Lennon–McCartney partnership. He described its meaning as "about people moaning about the weather all the time".[3]

| "Rain" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

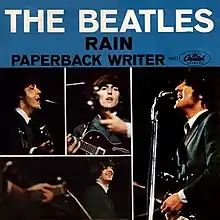

US picture sleeve (reverse) | ||||

| Single by the Beatles | ||||

| A-side | "Paperback Writer" | |||

| Released | 30 May 1966 | |||

| Recorded | 14 & 16 April 1966 | |||

| Studio | EMI, London | |||

| Genre | Psychedelic rock[1][2] | |||

| Length | 2:59 | |||

| Label |

| |||

| Songwriter(s) | Lennon–McCartney | |||

| Producer(s) | George Martin | |||

| The Beatles UK singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| The Beatles US singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Promotional film | ||||

| "Rain" on YouTube | ||||

The song's recording contains a slowed-down rhythm track, a droning bass line and backwards vocals. Its release marked the first time that reversed sounds appeared in a pop song, although the Beatles used the same technique on the Revolver track "Tomorrow Never Knows", recorded days earlier.[4] Ringo Starr considers "Rain" his best recorded drum performance. Three promotional films were created for the song, and they are considered among the early precursors of music videos.

Background and inspiration

Commenting on "Rain", John Lennon said it addressed "People moaning because ... they don't like the weather".[5] Another interpretation is that the song's "rain" and "sun" are phenomena experienced during a benign LSD trip.[6] Lennon had sung of the importance of mind over matter in the Beatles' 1963 song "There's a Place"; with "Rain", he furthered this idea through the influence of hallucinogenic drugs.[7] Author Nicholas Schaffner recognises it as the first Beatles song to portray the material world as an illusion, a theme Lennon and George Harrison explored at length during the band's psychedelic period.[8]

In an early-1970s article on the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership, "Rain" was one of the songs Lennon said he wrote alone.[9] According to Paul McCartney's recollection in his 1997 authorised biography Many Years from Now, the pair collaborated on it, and the song's authorship was "70–30 to John".[10] In what Beatles biographer Steve Turner deems an oversimplification that ignores the philosophical aspect, McCartney recalled: "Songs have traditionally treated rain as a bad thing and what we got on to was that it's no bad thing. There's no greater feeling than the rain dripping down your back."[11]

Composition

According to musicologist Alan Pollack, although the Beatles recording has "no sitars or other ethnic 'world music' instruments", "Rain" strongly evokes the style of Indian classical music through its "droning harmony and the, at times florid tune".[12] Ethnomusicologist David Reck recognises the song as "a more subtle absorption of Orientalism" in comparison with "Tomorrow Never Knows" and "Love You To", but one nevertheless possessing an Indian sound through Harrison's distorted lead guitar, Ringo Starr's drumming, and the use of reverse tape effects.[13][nb 1] Lennon's singing also draws on the flat timbre and ornamentation, in the form of gamaka, of Hindustani vocal music.[14]

Set in the key of G major (the final mix pitches it about a quarter of a semitone below this, while the backing track was taped much faster, in A sharp), the song begins with what Pollack calls "a ra-ta-tat half-measure's fanfare of solo snare drums", followed by a guitar intro of the first chord. The verses are nine measures long, and the song is in 4

4 time. Each verse is based on the G, C and D chords (I, IV, and V). The refrain contains only I and IV chords, and is twelve measures long (the repetition of a six-measure pattern). The first two measures are the G chord. The third and fourth measures are the C chord in the so-called 6

4 (second) inversion. The fifth and sixth measures return to the G chord. Pollack says the refrain seems slower than the verse, though it is at the same tempo, an illusion achieved by "the change of beat for the first four measures from its erstwhile bounce to something more plodding and regular".[12]

After four verses and two refrains, a short solo for guitar and drums is played, with complete silence for one beat. Following this, the music returns accompanied by a portion of singing for which the recording is reversed.[12]

Allan Kozinn describes McCartney's bass as "an ingenious counterpoint that takes him all over the fretboard ... while Lennon and McCartney harmonize in fourths on a melody with a slightly Middle Eastern tinge, McCartney first points up the song's droning character by hammering on a high G (approached with a quick slide from the F natural just below it), playing it steadily on the beat for twenty successive beats."[15]

Recording

The Beatles began recording "Rain" at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios) in London on 14 April 1966, in the same session as "Paperback Writer". They completed the track on 16 April, with a series of overdubs before mixing on the same day.[16] At that time, the band were enthusiastic about experimenting in the studio to achieve new sounds and effects.[17][18] These experiments were showcased on their seventh album, Revolver.[19] Geoff Emerick, who was the engineer for both sessions, described one technique he used to alter the sonic texture of the recording by taping the backing track "faster than normal". When played back, slightly slower than the usual speed, "the music had a radically different tonal quality."[20] The opposite technique was used to alter the tone of Lennon's lead vocal: it was recorded with the tape machine slowed down, making Lennon's voice sound higher when played back.[21]

Lennon played a 1965 Gretsch Nashville, McCartney a 1964 Rickenbacker 4001S bass, Harrison a 1964 Gibson SG, and Starr used Ludwig drums.[22][23] To boost the bass signal, Emerick recorded McCartney's amplifier via a loudspeaker, which EMI technical engineer Ken Townsend had reconfigured to serve as a microphone.[24] Although this technique was used only on the two songs selected for the standalone single,[25] an enhanced bass sound was a characteristic of much of Revolver.[26]

The increased volume of the bass guitar contravened EMI regulations, which were born out of concern that the powerful sound would cause a record buyer's stylus to jump.[27] The "Paperback Writer" / "Rain" single was therefore the first release to use a device invented by the maintenance department at EMI called Automatic Transient Overload Control (ATOC).[28] The new device allowed the record to be cut at a louder volume than any other single up to that time.[20]

Backwards sounds

The coda of "Rain" includes backwards vocals,[29] which Lennon later stated was the first use of this technique on a record.[30][nb 2] Edited together from Lennon's vocal track, the backwards portion consists of him singing the word "sunshine", then a drawn-out "rain" taken from one of the choruses,[32] and finally the song's opening line, "If the rain comes they run and hide their heads".[23] In author Robert Rodriguez's description, accompanied by the backing vocalists singing the song title on another track, Lennon's vocal "evoked the sound of a blissed-out zealot speaking in tongues in a trancelike state".[33]

Both Lennon and producer George Martin claimed credit for the idea.[26][34] Lennon said in 1966:

After we'd done the session on that particular song – it ended at about four or five in the morning – I went home with a tape to see what else you could do with it. And I was sort of very stoned and tired, you know, not knowing what I was doing, and I just happened to put it on my own tape recorder and it came out backwards. And I liked it better. So that's how it happened.[35][36]

Harrison confirmed Lennon's creative accident,[37] as did Emerick,[20] but Martin told Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn in 1987:

I was always playing around with tapes and I thought it might be fun to do something extra with John's voice. So I lifted a bit of his main vocal off the four-track, put it on another spool, turned it around and then slid it back and forth until it fitted. John was out at the time but when he came back he was amazed.[16]

Lennon repeated his version of events in a 1968 interview with Jonathan Cott of Rolling Stone.[38][nb 3] In a 1980 interview, Lennon recalled:

I got home from the studio and I was stoned out of my mind on marijuana and, as I usually do, I listened to what I'd recorded that day. Somehow I got it on backwards and I sat there, transfixed, with the earphones on, with a big hash joint. I ran in the next day and said, "I know what to do with it, I know ... Listen to this!" So I made them all play it backwards. The fade is me actually singing backwards with the guitars going backwards. [Singing backwards] Sharethsmnowthsmeaness ... [Laughter] That one was the gift of God, of Ja, actually, the god of marijuana, right? So Ja gave me that one.[39]

Regardless of who is credited for the technique, "from that point on", Emerick wrote, "almost every overdub we did on Revolver had to be tried backwards as well as forwards."[5][nb 4]

Release and reception

"Rain" was released as the B-side to "Paperback Writer" in the United States on 30 May 1966 (as Capitol 5651)[41] and in the UK on 10 June.[21][42] It was the Beatles' first UK single since the "Day Tripper" / "We Can Work It Out" double A-side in December 1965.[21][43] The new record showed profound changes in the Beatles' image, after the band had spent 1966 largely out of the public eye.[44] Music journalist Jon Savage describes the two tracks as "saturated in clanging guitar and Indian textures", and each reflective of a different side of "the psychedelic coin".[45][nb 5] In author Shawn Levy's description, as a prelude to Revolver, the single offered the first clue of the Beatles' transformation into "the world's first household psychedelics, avatars of something wilder and more revolutionary than anything pop culture had ever delivered before".[46] Cash Box described the song as a "soulful, medium-paced, effectively-rendered blueser."[47]

In the United States, the song peaked at number 23 on the Billboard Hot 100 on 9 July 1966,[48] and remained in that position the following week.[49] The "Paperback Writer" single reached number 1 in the UK and the US,[50] as well as Australia and West Germany.[51]

Rolling Stone ranked "Rain" 469th in its list of "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time" in 2010 and 463rd in 2004.[52] On a similar list compiled by the New York radio station Q104.3, the song appeared at number 382.[53] Both Ian MacDonald and Rolling Stone described Starr's drumming on the track as "superb",[54][55] while Richie Unterberger of AllMusic praises his "creative drum breaks".[56] In 1984, Starr said: "I think it's the best out of all the records I've ever made. 'Rain' blows me away … I know me and I know my playing … and then there's 'Rain'."[57] In his article on the band's singles, Alexis Petridis of The Guardian describes the song as "simultaneously thunderous and dreamy psych", and "perhaps the best Beatles B-side of all".[58] "Rain" was ranked 20th in Mojo's list of "The 101 Greatest Beatles Songs", compiled in 2006 by a panel of critics and musicians. The magazine's editors credited it with launching a "countercultural downpour".[59]

Music critic Jim DeRogatis describes the track as "the Beatles' first great psychedelic rock song".[60] Music historian Simon Philo recognises its release as marking "the birth of British psychedelic rock", as well as a forerunner to the unprecedented studio exploration and Indian aesthetic of "Tomorrow Never Knows" and "Love You To", respectively.[61] It has been noted for its slowed-down rhythm track and backwards vocals, anticipating the studio experimentation of "Tomorrow Never Knows" and other songs on Revolver, which was released in August 1966.[16][22] Musicologist Walter Everett cites its closing section as an example of how the Beatles pioneered the "fade-out–fade-in coda", a device used again by them on "Strawberry Fields Forever" and "Helter Skelter", and by Led Zeppelin on "Thank You".[62] From its introduction in "Rain", the Hindustani gamaka vocal ornamentation was adopted by several bands in the late 1960s, including the Moody Blues (on "The Sun Set"), the Hollies ("King Midas in Reverse") and Crosby, Stills & Nash ("Guinnevere").[63]

"Rain" was first mixed in stereo in December 1969[64] for its inclusion on the US compilation album Hey Jude early the following year.[65] The track subsequently appeared on Rarities in the UK[23] and the Past Masters, Volume Two CD.[66][67]

Promotional films

The Beatles created three promotional films for "Rain",[68] following on from their first attempts with the medium for their December 1965 single.[69][70] Authors Mark Hertsgaard and Bob Spitz both recognise the 1966 promos for "Paperback Writer" and "Rain" as the first examples of music videos.[71][72][nb 6] In the case of "Rain", it marked a rare instance where the Beatles prepared a clip for a B-side, later examples being "Revolution" and "Don't Let Me Down".[74]

The films were directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg, who had worked with the band on the television programme Ready Steady Go![75] One shows the Beatles walking and singing in the gardens and conservatory of Chiswick House in west London, and was filmed on 20 May.[76][77] The other two clips feature the band performing on a sound stage at EMI Studios on 19 May; one was filmed in colour for The Ed Sullivan Show and the other in black and white for broadcast in the UK.[76][78] McCartney was injured in a moped accident on 26 December 1965,[79] six months before the filming of "Rain", and close-ups in the film reveal a chipped tooth.[80] McCartney's appearance in the film played a role in the "Paul is dead" rumours from 1969.[23] The band also promoted the single with a rare TV appearance,[81] miming to both songs on the BBC show Top of the Pops on 16 June.[82][83]

The Beatles' Anthology documentary video includes an edit combining the Chiswick House promo for "Rain" with shots from the two black-and-white EMI clips and unused colour footage from the 20 May filming.[84] The new edit also employs rhythmic fast cuts.[85] Unterberger writes that this creates an impression that the 1966 promos were more technically complex, fast-paced and innovative than was the case. For example, the backwards film effects are 1990s creations. Such effects were actually first deployed in the "Strawberry Fields Forever" promotional film of January 1967.[86]

Covers, samples and media references

Dan Ar Braz covered "Rain" on his 1979 album The Earth's Lament, and later performed it with Fairport Convention at the Cropredy Festival in 1997.[87] Polyrock covered the song on their second album Changing Hearts (1981). Todd Rundgren has also covered the song,[23] as has the late Dan Fogelberg, who reprised it as part of his own cover of "Rhythm of the Rain". Shonen Knife covered the song on their 1991 album 712. Aloe Blacc sings it as Boris the Frog in the eponymous Beat Bugs episode 3b.

Andy Partridge of XTC has said that "Rain" was an inspiration on his 1980 song "Towers of London".[88] In his commentary with Mojo's selection of the best Beatles songs, Partridge recalled that on the night after Lennon was murdered in December 1980, the band played a gig at Liverpool, where they incorporated "Rain" in the coda to "Towers of London"; Partridge added, "I felt torn apart and had tears rolling down my face."[59] U2 played the song in whole or in part throughout many of their tours, usually during outdoor concerts when it has started to rain.[89] Pearl Jam improvised "Rain" into their song "Jeremy" during their 1992 Pinkpop Festival show and played it in full at the 2012 Isle of Wight Festival. Kula Shaker covered the song live at Reading Festival in 1996. The Grateful Dead played it twenty times throughout the early 1990s. Shoegaze band Chapterhouse covered the song for on their 1990 EP Sunburst.

The Beatles tribute act Rain derives their name from the song.[90] Oasis first named themselves the Rain after the Beatles track.[23] In music critic Chris Ingham's view, Oasis went on to add "a dash of Slade" to "Rain" and "base their entire style on it".[26]

Personnel

According to Ian MacDonald:[22]

- John Lennon – lead and backing vocals, rhythm guitar

- Paul McCartney – backing vocals, bass

- George Harrison – backing vocals, lead guitar

- Ringo Starr – drums, tambourine

Charts

| Chart (1966) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Belgium (Ultratop 50 Wallonia)[91] | 12 |

| US Billboard Hot 100[92] | 23 |

| US Cash Box Top 100[93] | 31 |

Notes

- Pollack likens the sound of the guitar to both an Indian tambura and "pipes".[12]

- The hit novelty song "They're Coming to Take Me Away, Ha-Haaa!", where side B is side A played backwards, was released in late July 1966.[31]

- Lennon told Cott: "I got home about five in the morning, stoned out of me head ... I staggered up to me tape recorder and put it on [the wrong way 'round], and I was in a trance in the earphones, what is it, what is it ... I really wanted the whole song backwards ... so we tagged it onto the end.[38]

- Martin reaffirmed his own account in an interview with Steve Turner, saying, "I can tell you – I created that." According to Turner, Martin cited experiments he had made with tape manipulation before working with the Beatles, such as the 1962 BBC Radiophonic Workshop single "Time Beat".[40]

- Savage describes McCartney's "Paperback Writer" as a "tricksy, fast, Swinging London satire", in contrast to the "deeper and darker" "Rain" and its evocation of "an enlightened or narcotic acceptance".[45]

- Referring to these clips, along with others the Beatles made during the mid 1960s, Harrison stated in The Beatles Anthology, "So I suppose, in a way, we invented MTV."[73]

References

- Williams, Stereo (5 August 2016). "The Beatles' 'Revolver' Turns 50: A Psychedelic Masterpiece That Rewrote the Rules of Rock". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "The 50 Best Beatles songs". Time Out London. 24 May 2018. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- The Beatles 2000, p. 212.

- Reising & LeBlanc 2009, pp. 94, 95.

- Rolling Stone staff (19 September 2011). "100 Greatest Beatles Songs: 88. 'Rain'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- MacDonald 2005, pp. 196–97.

- Turner 1999, p. 102.

- Schaffner 1978, pp. 54–55.

- "Lennon–McCartney Songalog: Who Wrote What". Hit Parader. Winter 1977 [April 1972]. pp. 38–41. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- Miles 1997, p. 280.

- Turner 2016, p. 154.

- Pollack, Alan W. (12 December 1993). "Notes on 'Paperback Writer' and 'Rain'". Soundscapes. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Reck 2016, pp. 66–67.

- Reck 2016, p. 67.

- Allan Kozinn (1995). The Beatles. London: Phaidon. p. 143.

- Lewisohn 2005, p. 74.

- Gould 2007, pp. 328–29.

- Winn 2009, p. 11.

- Lewisohn 2005, pp. 70, 74.

- Emerick 2006, p. 117.

- Lewisohn 2005, p. 83.

- MacDonald 2005, p. 196.

- Fontenot, Robert (2007). "'Rain' – The history of this classic Beatles song". oldies.about.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Hertsgaard 1996, p. 180.

- Rodriguez 2012, p. 119.

- Ingham 2006, p. 191.

- Turner 2016, p. 155.

- Rodriguez 2012, pp. 115–16, 119.

- Rodriguez 2012, p. 120.

- Sheff 2010, p. 197.

- Savage 2015, pp. 543, 559.

- Turner 2016, p. 156.

- Rodriguez 2012, p. 121.

- Miles 2001, p. 233.

- "Revolver". beatlesinterviews.org. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- Gilliland 1969, show 37, track 4.

- Rodriguez 2012, pp. 120–21.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 55.

- Sheff 2010, p. 198.

- Turner 2016, pp. 155–56.

- Miles 2001, p. 232.

- Castleman & Podrazik 1976, pp. 53–54.

- Turner 2016, p. 150.

- Gould 2007, p. 325.

- Savage 2015, p. 138.

- Levy 2002, pp. 240–41.

- "CashBox Record Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. 4 June 1966. p. 8. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- "The Hot 100: July 9th 1966". billboard.com. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 349.

- Schaffner 1978, p. 69.

- Turner 1999, p. 101.

- Rolling Stone staff (11 December 2003). "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time (2004): 469. The Beatles, 'Rain'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- "The Top 1,043 Classic Rock Songs of All Time: Dirty Dozenth Edition". Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- MacDonald 2005, p. 198.

- Rolling Stone 2004a.

- Unterberger 2007.

- Sheffield, Rob (14 April 2010). "Ringo's Greatest Hit". rollingstone.com. Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Petridis, Alex (26 September 2019). "The Beatles' Singles – Ranked!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- Alexander, Phil; et al. (July 2006). "The 101 Greatest Beatles Songs". Mojo. p. 80.

- DeRogatis 2003, p. 43.

- Philo 2015, pp. 111–12.

- Everett 2009, p. 154.

- Everett 1999, p. 44.

- Everett 1999, p. 45.

- Winn 2009, pp. 11–12.

- Lewisohn 2005, p. 201.

- Winn 2009, p. 12.

- Unterberger 2006, p. 319.

- Ingham 2006, pp. 164–65.

- Rodriguez 2012, pp. 159–60.

- Hertsgaard 1996, p. 8.

- Spitz 2005, pp. 609–10.

- The Beatles 2000, p. 214.

- Unterberger 2006, p. 318.

- Miles 2001, p. 231.

- Neaverson 2009.

- Turner 2016, p. 183.

- Winn 2009, p. 20.

- Miles 2001, p. 221.

- Rodriguez 2012, pp. 161–62.

- Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 257.

- Savage 2015, pp. 317–18.

- Everett 1999, p. 68.

- Winn 2009, p. 21.

- Unterberger 2006, p. 320.

- Unterberger 2006, p. 322.

- Sleger.

- Bernhardt, Todd (16 December 2007). "Andy and Dave discuss 'Towers of London'". Chalkhills. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- U2gigs.com 2010.

- Isherwood, Charles. "Another Long and Winding Detour," Archived 9 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine New York Times (26 OCT. 2010).

- "The Beatles – Rain" (in French). Ultratop 50. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- "The Beatles Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- "Cash Box Top 100 Singles: June 25, 1966". Cashbox. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

Sources

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-2684-6. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Castleman, Harry; Podrazik, Walter J. (1976). All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25680-8.

- DeRogatis, Jim (2003). Turn on Your Mind: Four Decades of Great Psychedelic Rock. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-0-634-05548-5.

- Emerick, Geoff; Massey, Howard (2006). Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-59240-179-6.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512941-0. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Everett, Walter (2009). The Foundations of Rock: From "Blue Suede Shoes" to "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes". New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531024-5.

- Gilliland, John (1969). "The Rubberization of Soul: The great pop music renaissance" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America. London: Piatkus. ISBN 978-0-7499-2988-6. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Hertsgaard, Mark (1996). A Day in the Life: The Music and Artistry of the Beatles. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-33891-9.

- Ingham, Chris (2006). The Rough Guide to the Beatles. London: Rough Guides/Penguin. ISBN 978-1-84836-525-4.

- Levy, Shawn (2002). Ready, Steady, Go!: Swinging London and the Invention of Cool. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-1-84115-226-4.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2005) [1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 978-0-7537-2545-0.

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (2nd rev. ed.). London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-1-84413-828-9.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now. New York, NY: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-5248-0.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- Neaverson, Bob (2009). "Beatles Videography". Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- Philo, Simon (2015). British Invasion: The Crosscurrents of Musical Influence. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-8626-1. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- "Rain". Rolling Stone. 9 December 2004a. Archived from the original on 28 December 2006.

- "Rain". U2gigs.com. 2010. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- Reck, David (2016) [2008]. "The Beatles and Indian Music". In Julien, Olivier (ed.). Sgt. Pepper and the Beatles: It Was Forty Years Ago Today. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7546-6708-7.

- Reising, Russell; LeBlanc, Jim (2009). "Magical Mystery Tours, and Other Trips: Yellow submarines, newspaper taxis, and the Beatles' psychedelic years". In Womack, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68976-2.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2012). Revolver: How the Beatles Reimagined Rock 'n' Roll. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61713-009-0. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- "The RS 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. 9 December 2004b. Archived from the original on 25 October 2006. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Savage, Jon (2015). 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-27763-6.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Sheff, David (2010) [1981]. All We Are Saying: The Last Major Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. New York, NY: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4299-5808-0.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. New York, NY: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-80352-6.

- Turner, Steve (1999). A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song. New York, NY: Carlton/HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-273698-1.

- Turner, Steve (2016). Beatles '66: The Revolutionary Year. New York, NY: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-247558-9.

- Unterberger, Richie (2006). The Unreleased Beatles: Music & Film. San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-892-6.

- Unterberger, Richie (2007). "Review of "Rain"". Allmusic. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- Sleger, Dave. "The Cropredy Box Review". Allmusic. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Winn, John C. (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.