Red River (1948 film)

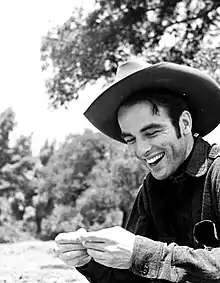

Red River is a 1948 American Western film, directed and produced by Howard Hawks and starring John Wayne and Montgomery Clift. It gives a fictional account of the first cattle drive from Texas to Kansas along the Chisholm Trail. The dramatic tension stems from a growing feud over the management of the drive between the Texas rancher who initiated it (Wayne) and his adopted adult son (Clift).

| Red River | |

|---|---|

_poster.jpg.webp) Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Howard Hawks |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Chisholm Trail 1946 The Saturday Evening Post by Borden Chase |

| Produced by | Howard Hawks |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Russell Harlan |

| Edited by | Christian Nyby |

| Music by | Dimitri Tiomkin |

Production company | Monterey Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date | August 26, 1948[1] |

Running time | 133 minutes (Pre-release) 127 minutes (Theatrical) |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

|

| Budget | $2.7 million[2] |

| Box office | $4,506,825 (U.S. and Canada rentals)[3][4] |

The film's supporting cast features Walter Brennan, Joanne Dru, Coleen Gray, Harry Carey, John Ireland, Hank Worden, Noah Beery Jr., Harry Carey Jr. and Paul Fix. Borden Chase and Charles Schnee wrote the screenplay based on Chase's original story (which was first serialized in The Saturday Evening Post in 1946 as "Blazing Guns on the Chisholm Trail").

Upon its release, Red River was both a commercial and a critical success and was nominated for two Academy Awards.[5] In 1990, Red River was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[6][7] Red River was selected by the American Film Institute as the fifth-greatest Western of all time in the AFI's 10 Top 10 list in 2008.

Plot

Thomas Dunson wants to start a cattle ranch in Texas. Shortly after he begins his journey to Texas with his trail hand Nadine Groot, Dunson learns that his love interest Fen was killed in an Indian attack. He had told Fen to stay behind with the California-bound wagon train, with the understanding that he would send for her later.

That night, Dunson and Groot fend off an attack by Indians. On the wrist of one, Dunson finds a bracelet he had been left by his late mother, which he had given to Fen as he left the train. The next day, an orphaned boy named Matthew Garth (played as a boy by Mickey Kuhn) wanders into Dunson and Groot's camp. He is the sole survivor of the wagon train, and Dunson adopts him.

Dunson, Groot, and Matt enter Texas by crossing the Red River. They settle in deep South Texas near the Rio Grande. Dunson names his new spread the Red River D, after his chosen cattle brand for his herd. He promises to add M (for Matt) to the brand, once Matt has earned it.

Fourteen years pass, and Dunson has a fully operational cattle ranch, but he is broke as a result of widespread poverty in the southern United States following the Civil War. He decides to drive his massive herd hundreds of miles north to the railhead at Sedalia, Missouri, where he believes they will fetch a good price. After Dunson hires men to help, including professional gunman Cherry Valance, the northward drive starts.

Along the way, they encounter many troubles. One of the men, Bunk Kenneally, raises a maudlin ruckus in one of the wagons, triggering a stampede. This leads to the death of Dan Latimer. When Dunson attempts to whip Bunk as punishment for causing the stampede, the latter draws his gun. Matt shoots and wounds Bunk, probably saving his life because Dunson certainly would have shot to kill. Bunk is fired and sent home. Dunson tells Matt that he is weak because he did not kill his man.

Continuing with the drive, Valance relates that the railroad has reached Abilene, Kansas, which is much closer than Sedalia. When Dunson confirms that Valance had not actually seen the railroad, he ignores the rumor in favor of continuing to Missouri.

Dunson's tyrannical leadership style begins to affect the men, with his shooting three drovers who try to quit the drive. After Dunson announces he intends to lynch two men who stole supplies, tried to desert, and were captured by Valance, Matt rebels. With the support of the cowhands, he takes control of the herd in order to drive it along the Chisholm Trail to the hoped-for railhead in Abilene. Valance and Buster become his right-hand men. Dunson curses Matt and promises to kill him when they next meet. The drive turns toward Abilene, leaving Dunson behind.

On the way to Abilene, Matt and his men repel an Indian attack on a wagon train made up of gamblers and dance hall girls. One of the people they save is Tess Millay, who falls in love with Matt. They spend a night together, and he gives her Dunson's mother's bracelet. Eager to beat Dunson to Abilene, he leaves early in the morning, the same way Dunson had left his lady love with the wagon train 14 years before.

Later, Tess encounters Dunson, who has followed Matt's trail and now sees her wearing his mother's bracelet. Weary and emotional, he tells Tess what he wants most of all is a son. She offers to bear him one if he will abandon his pursuit of Matt. Dunson sees in her the anguish that Fen had expressed when he left her, and decides to resume the chase with Tess accompanying him.

When Matt reaches Abilene, he finds the town has been awaiting the arrival of such a herd to buy. He accepts an offer for the cattle and meets Tess again. The next morning, Dunson arrives in Abilene with his posse. Dunson and Matt begin a fistfight, which Tess interrupts, demanding that they realize the love that they share. Making peace, Dunson advises Matt to marry Tess and tells him that when they get back to the ranch, he will incorporate an M into the brand, telling Matt that he had earned it.

Cast

- John Wayne as Thomas Dunson

- Montgomery Clift as Matthew "Matt" Garth

- Walter Brennan as Nadine Groot

- Joanne Dru as Tess Millay

- Coleen Gray as Fen

- Harry Carey as Mr. Melville, representative of the Greenwood Trading Company[8]

- John Ireland as Cherry Valance

- Noah Beery Jr. as Buster McGee (Dunson Wrangler)

- Harry Carey Jr. as Dan Latimer (Dunson Wrangler)

- Chief Yowlachie as Two Jaw Quo (Dunson Wrangler)

- Paul Fix as Teeler Yacey (Dunson Wrangler)

- Hank Worden as Sims Reeves (Dunson Wrangler)

- Ray Hyke as Walt Jergens (Dunson Wrangler)

- Wally Wales as Old Leather (Dunson Wrangler)

- Mickey Kuhn as Young Matt

- Robert M. Lopez as an Indian

- Uncredited

- Shelley Winters as Dance Hall Girl in Wagon Train

- Dan White as Laredo (Dunson Wrangler)

- Tom Tyler as Quitter (Dunson Wrangler)

- Ray Spiker as Wagon Train Member

- Glenn Strange as Naylor (Dunson Wrangler)

- Chief Sky Eagle as Indian Chief

- Ivan Parry as Bunk Kenneally (Dunson Wrangler)

- Lee Phelps as Gambler

- William Self as Sutter (Wounded Wrangler)

- Carl Sepulveda as Cowhand (Dunson Wrangler)

- Pierce Lyden as Colonel's Trail Boss

- Harry Cording as Gambler

- George Lloyd as Rider with Melville

- Frank Meredith as Train Engineer

- John Merton as Settler

- Jack Montgomery as Drover at Meeting

- Paul Fierro as Fernandez (Dunson Wrangler)

- Richard Farnsworth as Dunston Rider

- Lane Chandler as Colonel, the wagon master of the pre-Civil War wagon train

- Davison Clark as Mr. Meeker, one of Dunson's fellow ranchers

- Guy Wilkerson as Pete (Dunson Wrangler)

Production

Red River was filmed in 1946, copyrighted in 1947, but not released until September 30, 1948. Footage from Red River was later incorporated into the opening montage of Wayne's last film, The Shootist, to illustrate the backstory of Wayne's character. The film was nominated for Academy Awards for Best Film Editing (Christian Nyby) and Best Writing, Motion Picture Story (Borden Chase). John Ford, who worked with Wayne on many films such as Stagecoach, The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, was so impressed with Wayne's performance that he is reported to have said, "I didn't know the big son of a bitch could act!"[9]

The film was shot in black and white rather than color, because director Howard Hawks found Technicolor technology to be too "garish" for the realistic style desired.[10] Second unit director Arthur Rosson was given credit in the opening title crawl as co-director. He shot parts of the cattle drive and some action sequences.[11] The film's ending differed from that of the original story. In Chase's original Saturday Evening Post story, published in 1946 as "Blazing Guns on the Chisholm Trail", Valance shoots Dunson dead in Abilene and Matt takes his body back to Texas to be buried on the ranch.

Alternate versions

During the production and while the film was still being shot, Hawks was not satisfied with the editing and asked Christian Nyby to take over cutting duties. Nyby worked for about a year on the project. After production, the pre-release version was 133 minutes and included book-style transitions. This version was briefly available for television in the 1970s, but was believed to be lost. It was rediscovered after a long search as a Cinémathèque Française 35 mm print, and released by the Criterion Collection.[12]

Before the film could be released, Howard Hughes sued Hawks, claiming that the climactic scene between Dunson and Matt was too similar to the film The Outlaw (1943), which both Hawks and Hughes had worked on.[13] Hughes prepared a new 127-minute cut, which replaced the book inserts with spoken narration by Walter Brennan.[14] Nyby salvaged the film by editing in some reaction shots, which resulted in the original theatrical version.[14] This version was lost, and the 133-minute pre-release version was seen on television broadcasts and home video releases. The original theatrical cut was reassembled by Janus Films (in co-operation with UA parent company MGM) for their Criterion Collection Blu-ray/DVD release on May 27, 2014.[12]

Film historian Peter Bogdanovich interviewed Hawks in 1972, and was led to believe that the narrated theatrical version was the director's preferred cut.[14] This view was upheld by Geoffrey O'Brien in his 2014 essay for the Criterion release.[13] Contrarily, some, including film historian Gerald Mast, argue that Hawks preferred the 133-minute version.[15] Mast points out that this is told from an objective third-person point of view, while the shorter cut has Brennan's character narrating scenes he could not have witnessed.[14] Filmmaker/historian Michael Schlesinger, in his essay on the film for the Library of Congress' National Film Registry, argues that when Bogdanovich interviewed Hawks, the director "was 76 and in declining health", when he was prone to telling tall tales. Schlesinger also points out that Hughes's shortened version was prepared for overseas distribution because it is easier to replace narration than printed text.[14]

Soundtrack

The song "Settle Down", by Dimitri Tiomkin (music) and Frederick Herbert (lyric), heard over the credits and at various places throughout the film score, was later adapted by Tiomkin, with a new lyric by Paul Francis Webster, as "My Rifle, My Pony, and Me" in the 1959 film Rio Bravo for an onscreen duet by Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson as John Wayne and Walter Brennan look on.[16]

Reception

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times gave the film a mostly positive review, praising the main cast for "several fine performances" and Hawks' direction for "credible substance and detail." He only found a "big let-down" in the Indian wagon train attack scene, lamenting that the film had "run smack into 'Hollywood' in the form of a glamorized female, played by Joanne Dru."[17] Variety called it "a spectacle of sweeping grandeur" with "a first rate script," adding, "John Wayne has his best assignment to date and he makes the most of it."[18] John McCarten of The New Yorker found the film "full of fine Western shots," with the main cast's performances "all first-rate."[19] Harrison's Reports called the film "an epic of such sweep and magnitude that it deserves to take its place as one of the finest pictures of its type ever to come out of Hollywood."[20]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes the film holds an approval rating of 100% rating, based on 29 reviews, with an average rating of 8.80/10.[21]

Roger Ebert considered it one of the greatest Western films of all time.[22]

This movie was the last movie shown in the 1971 motion picture The Last Picture Show.

In 1990, Red River was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Red River was selected by the American Film Institute as the 5th greatest Western of all time in the AFI's 10 Top 10 list in 2008.

"Red River D" belt buckles

To commemorate their work on the film, director Howard Hawks had special Western belt buckles made up for certain members of the cast and crew of Red River. The solid silver belt buckles had a twisted silver wire rope edge, the Dunson brand in gold in the center, the words “Red River” in gold wire in the upper left and lower right corners, the initials of the recipients in the lower left corner, and the date "1946" in cut gold numerals in the upper right corner. Hawks gave full-sized (men's) buckles to John Wayne, his son David Hawks, Montgomery Clift, Walter Brennan, assistant director Arthur Rosson, cinematographer Russell Harlan, and John Ireland. Joanna Dru and Hawks' daughter Barbara were given smaller (ladies') versions of the buckle. According to David Hawks, other men's and women's buckles were distributed, but he can only confirm the family members and members of the cast and production team listed above received Red River D buckles.

Wayne and Hawks exchanged buckles as a token of their mutual respect. Wayne wore the Red River D belt buckle with the initials "HWH" in nine other movies including North to Alaska, Circus World, Hatari! Rio Bravo, El Dorado, McLintock!, and Rio Lobo.

In 1981, John Wayne's son Michael sent the buckle to a silversmith in order to have duplicates made for all of Wayne's children. While in the silversmith's care, it was stolen and has not been seen since. Red River D buckles, made by a number of sources, are among the most popular and sought after icons of John Wayne fans.[23]

See also

- Cimarron – 1931 film mentioned on poster

- The Covered Wagon – 1923 film mentioned on poster

- Han shot first

References

- "Red River". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- Thomas F. Brady. "Hollywood Deals: Prospects Brighten for United Artists – Budget Runs Wild and Other Matters", New York Times 1 Feb 1948, p. X5.

- Andreychuk, Ed (1997). The Golden Corral: A Roundup of Magnificent Western Films. McFarland & Company Inc. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-7864-0393-4.

- Cohn, Lawrence (October 15, 1990). "All Time Film Rental Champs". Variety. p. M-180. ISSN 0042-2738.

- Red River (1948) – Awards

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Gamarekian, Barbara (October 19, 1990). "Library of Congress Adds 25 Titles to National Film Registry". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- Grant, Barry Keith (2007). Film Genre: From Iconography to Ideology. London: Wallflower. p. 67. ISBN 978-1904764793.

- Nixon, Rob. "Pop Culture 101; Red River". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved October 7, 2022.

- French, Philip (October 27, 2013). "Red River". The Guardian. eISSN 1756-3224. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- Nixon, Rob. "Trivia & Fun Facts About Red River". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved October 7, 2022.

- Red River commemorative booklet, 2014, p. 27. Included as part of the Criterion Edition release.

- O'Brien, Geoffrey (May 27, 2014). "Red River: The Longest Drive". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Schlesinger, Michael. "Red River" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Mast, Gerald (1982). Howard Hawks, Storyteller. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503091-5. OCLC 8114578.

- Morris, Joan (October 29, 2010). "Joan's World: Missing lyrics from 'Red River' classic". The Mercury News. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- Crowther, Bosley (October 1, 1948). "The Screen in Review". The New York Times: 31.

- "Red River". Variety: 12. July 14, 1948.

- McCarten, John (October 9, 1948). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 111.

- "'Red River' with John Wayne, Montgomery Clift, Walter Brennan and Joanne Dru". Harrison's Reports: 114. July 17, 1948.

- "Red River". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- Ebert, Roger (March 1, 1998). "Great Movie; Red River". rogerebert.com. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- "History of the Red River D Buckle".

Further reading

- Eagan, Daniel (2010). "Red River essay" in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, London: A & C Black. ISBN 0826429777, pp. 417–19.

- Pippin, Robert B. (2010). Hollywood Westerns and American Myth: The Importance of Howard Hawks and John Ford for Political Philosophy. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14577-9.

External links

- Red River at IMDb

- Red River at AllMovie

- Red River at the TCM Movie Database

- Red River at the American Film Institute Catalog

- "Red River". on Lux Radio Theatre: March 7, 1949. 14 Mb download.