Repurchase agreement

A repurchase agreement, also known as a repo, RP, or sale and repurchase agreement, is a form of short-term borrowing, mainly in government securities. The dealer sells the underlying security to investors and, by agreement between the two parties, buys them back shortly afterwards, usually the following day, at a slightly higher price.

| Part of a series on |

| Finance |

|---|

|

|

The repo market is an important source of funds for large financial institutions in the non-depository banking sector, which has grown to rival the traditional depository banking sector in size. Large institutional investors such as money market mutual funds lend money to financial institutions such as investment banks, either in exchange for (or secured by) collateral, such as Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities held by the borrower financial institutions. An estimated $1 trillion per day in collateral value is transacted in the U.S. repo markets.[1][2]

In 2007–2008, a run on the repo market, in which funding for investment banks was either unavailable or at very high interest rates, was a key aspect of the subprime mortgage crisis that led to the Great Recession.[3] During September 2019, the U.S. Federal Reserve intervened in the role of investor to provide funds in the repo markets, when overnight lending rates jumped due to a series of technical factors that had limited the supply of funds available.[1][4][2]

Structure and other terminology

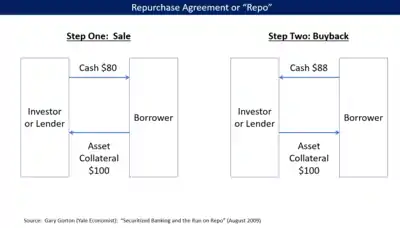

In a repo, the investor/lender provides cash to a borrower, with the loan secured by the collateral of the borrower, typically bonds. In the event the borrower defaults, the investor/lender gets the collateral. Investors are typically financial entities such as money market mutual funds, while borrowers are non-depository financial institutions such as investment banks and hedge funds. The investor/lender charges an interest rate called the "repo rate," lending $X and receiving back a greater amount $Y. Further, the investor/lender may demand collateral of greater value than the amount that they lend. This difference is the "haircut." These concepts are illustrated in the diagram and in the equations section. When investors perceive greater risks, they may charge higher repo rates and demand greater haircuts. A third party may be involved to facilitate the transaction; in this case, the transaction is referred to as a "tri-party repo."[3]

Specifically, in a repo the security-buying party B acts as a lender of cash, whereas the seller A is acting as a borrower of cash, using the security as collateral; in a reverse repo, security purchaser (A) is the lender of cash and (B) is the borrower of cash.[5] A repo is economically similar to a secured loan, with the buyer (effectively the lender or investor) receiving securities for collateral to protect himself against default by the seller. The party who initially sells the securities is effectively the borrower. Many types of institutional investors engage in repo transactions, including mutual funds and hedge funds.[6] Almost any security may be employed in a repo, though highly liquid securities are preferred as they are more easily disposed of in the event of a default and, more importantly, they can be easily obtained in the open market where the buyer has created a short position in the repo security by a reverse repo and market sale; by the same token, non liquid securities are discouraged.

Treasury or Government bills, corporate and Treasury/Government bonds, and stocks may all be used as "collateral" in a repo transaction. Unlike a secured loan, however, legal title to the securities passes from the seller to the buyer. Coupons (interest payable to the owner of the securities) falling due while the repo buyer owns the securities are, in fact, usually passed directly onto the repo seller. This might seem counter-intuitive, as the legal ownership of the collateral rests with the buyer during the repo agreement. The agreement might instead provide that the buyer receives the coupon, with the cash payable on repurchase being adjusted to compensate, though this is more typical of sell/buybacks.

Although the transaction is similar to a loan, and its economic effect is similar to a loan, the terminology differs from that applying to loans: the seller legally repurchases the securities from the buyer at the end of the loan term. However, a key aspect of repos is that they are legally recognised as a single transaction (important in the event of counterparty insolvency) and not as a disposal and a repurchase for tax purposes. By structuring the transaction as a sale, a repo provides significant protections to lenders from the normal operation of U.S. bankruptcy laws, such as the automatic stay and avoidance provisions.

A reverse repo is a repo with the roles of A and B exchanged.

The following table summarizes the terminology:

| Repo | Reverse repo | |

|---|---|---|

| Participant | Borrower Seller Cash receiver |

Lender Buyer Cash provider |

| Near leg | Sells securities | Buys securities |

| Far leg | Buys securities | Sells securities |

History

In the United States, repos have been used from as early as 1917 when wartime taxes made older forms of lending less attractive. At first, repos were used just by the Federal Reserve to lend to other banks, but the practice soon spread to other market participants. The use of repos expanded in the 1920s, fell away through the Great Depression and WWII, then expanded once again in the 1950s, enjoying rapid growth in the 1970s and 1980s in part due to computer technology.[7]

According to Yale economist Gary Gorton, repo evolved to provide large non-depository financial institutions with a method of secured lending analogous to the depository insurance provided by the government in traditional banking, with the collateral acting as the guarantee for the investor.[3]

In 1982, the failure of Drysdale Government Securities led to a loss of $285 million for Chase Manhattan Bank. This resulted in a change in how accrued interest is used in calculating the value of the repo securities. In the same year, the failure of Lombard-Wall, Inc. resulted in a change in the federal bankruptcy laws pertaining to repos.[8][9] The failure of ESM Government Securities in 1985 led to the closing of Home State Savings Bank in Ohio and a run on other banks insured by the private-insurance Ohio Deposit Guarantee Fund. The failure of these and other firms led to the enactment of the Government Securities Act of 1986.[10]

In 2007–2008, a run on the repo market, in which funding for investment banks was either unavailable or at very high interest rates, was a key aspect of the subprime mortgage crisis that led to the Great Recession.[3]

In July 2011, concerns arose among bankers and the financial press that if the 2011 U.S. debt ceiling crisis led to a default, it could cause considerable disruption to the repo market. This was because treasuries are the most commonly used collateral in the US repo market, and as a default would have downgraded the value of treasuries, it could have resulted in repo borrowers having to post far more collateral. [11]

During September 2019, the U.S. Federal Reserve intervened in the role of investor to provide funds in the repo markets, when overnight lending rates jumped due to a series of technical factors that had limited the supply of funds available.[1]

Market size

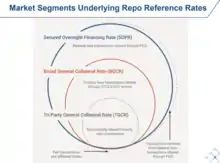

The New York Times reported in September 2019 that an estimated $1 trillion per day in collateral value is transacted in the U.S. repo markets.[1] The Federal Reserve Bank of New York reports daily repo collateral volume for different types of repo arrangements. As of 24 October 2019, volumes were: secured overnight financing rate (SOFR) $1,086 billion; broad general collateral rate (BGCR) $453 billion, and tri-party general collateral rate (TGCR) $425 billion.[2] These figures however, are not additive, as the latter 2 are merely components of the former, SOFR.[12]

The Federal Reserve and the European Repo and Collateral Council (a body of the International Capital Market Association) have tried to estimate the size of their respective repo markets. At the end of 2004, the US repo market reached US$5 trillion. Especially in the US and to a lesser degree in Europe, the repo market contracted in 2008 as a result of the financial crisis. But, by mid-2010, the market had largely recovered and, at least in Europe, had grown to exceed its pre-crisis peak.[13]

Repo expressed as mathematical formula

A repurchase agreement is a transaction concluded on a deal date tD between two parties A and B:

- (i) A will on the near date sell a specified security S at an agreed price PN to B

- (ii) A will on the far date tF (after tN) re-purchase S from B at a price PF which is already pre-agreed on the deal date.

If positive interest rates are assumed, the repurchase price PF can be expected to be greater than the original sale price PN.

The (time-adjusted) difference is called the repo rate, which is the annualized interest rate of the transaction. can be interpreted as the interest rate for the period between near date and far date.

Ambiguity in the usage of the term repo

The term repo has given rise to a lot of misunderstanding: there are two types of transactions with identical cash flows:

- (i) a sell-and-buy-back as well as,

- (ii) a collateralized borrowing.

The sole difference is that in (i) the asset is sold (and later re-purchased), whereas in (ii) the asset is instead pledged as a collateral for a loan: in the sell-and-buy-back transaction, the ownership and possession of S are transferred at tN from a A to B and in tF transferred back from B to A; conversely, in the collateralized borrowing, only the possession is temporarily transferred to B whereas the ownership remains with A.

Maturities of repos

There are two types of repo maturities: term, and open repo.

Term refers to a repo with a specified end date: although repos are typically short-term (a few days), it is not unusual to see repos with a maturity as long as two years.

Open has no end date which has been fixed at conclusion. Depending on the contract, the maturity is either set until the next business day and the repo matures unless one party renews it for a variable number of business days. Alternatively it has no maturity date – but one or both parties have the option to terminate the transaction within a pre-agreed time frame.

Types

Repo transactions occur in three forms: specified delivery, tri-party, and held in custody (wherein the "selling" party holds the security during the term of the repo). The third form (hold-in-custody) is quite rare, particularly in developing markets, primarily due to the risk that the seller will become insolvent prior to maturation of the repo and the buyer will be unable to recover the securities that were posted as collateral to secure the transaction. The first form—specified delivery—requires the delivery of a prespecified bond at the onset, and at maturity of the contractual period. Tri-party is essentially a basket form of transaction and allows for a wider range of instruments in the basket or pool. In a tri-party repo transaction, a third party clearing agent or bank is interposed between the "seller" and the "buyer". The third party maintains control of the securities that are the subject of the agreement and processes the payments from the "seller" to the "buyer."

Due bill/hold in-custody repo / bilateral repo

In a due bill repo, the collateral pledged by the (cash) borrower is not actually delivered to the cash lender. Rather, it is placed in an internal account ("held in custody") by the borrower, for the lender, throughout the duration of the trade. This has become less common as the repo market has grown, particularly owing to the creation of centralized counterparties. Due to the high risk to the cash lender, these are generally only transacted with large, financially stable institutions.

Tri-party repo

The distinguishing feature of a tri-party repo is that a custodian bank or international clearing organization, the tri-party agent, acts as an intermediary between the two parties to the repo. The tri-party agent is responsible for the administration of the transaction, including collateral allocation, marking to market, and substitution of collateral. In the US, the two principal tri-party agents are The Bank of New York Mellon and JP Morgan Chase, whilst in Europe the principal tri-party agents are Euroclear and Clearstream with SIX offering services in the Swiss market. The size of the US tri-party repo market peaked in 2008 before the worst effects of the crisis at approximately $2.8 trillion and by mid-2010 was about $1.6 trillion.[13]

As tri-party agents administer the equivalent of hundreds of billions of USD of global collateral, they have the scale to subscribe to multiple data feeds to maximise the universe of coverage. As part of a tri-party agreement the three parties to the agreement, the tri-party agent, the repo buyer (the Collateral Taker/Cash Provider, "CAP") and the repo seller (Cash Borrower/Collateral Provider, "COP") agree to a collateral management service agreement which includes an "eligible collateral profile".

It is this "eligible collateral profile" that enables the repo buyer to define their risk appetite in respect of the collateral that they are prepared to hold against their cash. For example, a more risk averse repo buyer may wish to only hold "on-the-run" government bonds as collateral. In the event of a liquidation event of the repo seller the collateral is highly liquid thus enabling the repo buyer to sell the collateral quickly. A less risk averse repo buyer may be prepared to take non investment grade bonds or equities as collateral, which may be less liquid and may suffer a higher price volatility in the event of a repo seller default, making it more difficult for the repo buyer to sell the collateral and recover their cash. The tri-party agents are able to offer sophisticated collateral eligibility filters which allow the repo buyer to create these "eligible collateral profiles" which can systemically generate collateral pools which reflect the buyer's risk appetite.[14]

Collateral eligibility criteria could include asset type, issuer, currency, domicile, credit rating, maturity, index, issue size, average daily traded volume, etc. Both the lender (repo buyer) and borrower (repo seller) of cash enter into these transactions to avoid the administrative burden of bi-lateral repos. In addition, because the collateral is being held by an agent, counterparty risk is reduced. A tri-party repo may be seen as the outgrowth of the 'due bill repo. A due bill repo is a repo in which the collateral is retained by the Cash borrower and not delivered to the cash provider. There is an increased element of risk when compared to the tri-party repo as collateral on a due bill repo is held within a client custody account at the Cash Borrower rather than a collateral account at a neutral third party.

Whole loan repo

A whole loan repo is a form of repo where the transaction is collateralized by a loan or other form of obligation (e.g., mortgage receivables) rather than a security.

Equity repo

The underlying security for many repo transactions is in the form of government or corporate bonds. Equity repos are simply repos on equity securities such as common (or ordinary) shares. Some complications can arise because of greater complexity in the tax rules for dividends as opposed to coupons.

Sell/buybacks and buy/sell backs

A sell/buyback is the spot sale and a forward repurchase of a security. It is two distinct outright cash market trades, one for forward settlement. The forward price is set relative to the spot price to yield a market rate of return. The basic motivation of sell/buybacks is generally the same as for a classic repo (i.e., attempting to benefit from the lower financing rates generally available for collateralized as opposed to non-secured borrowing). The economics of the transaction are also similar, with the interest on the cash borrowed through the sell/buyback being implicit in the difference between the sale price and the purchase price.

There are a number of differences between the two structures. A repo is technically a single transaction whereas a sell/buyback is a pair of transactions (a sell and a buy). A sell/buyback does not require any special legal documentation while a repo generally requires a master agreement to be in place between the buyer and seller (typically the SIFMA/ICMA commissioned Global Master Repo Agreement (GMRA)). For this reason, there is an associated increase in risk compared to repo. Should the counterparty default, the lack of agreement may lessen legal standing in retrieving collateral. Any coupon payment on the underlying security during the life of the sell/buyback will generally be passed back to the buyer of the security by adjusting the cash paid at the termination of the sell/buyback. In a repo, the coupon will be passed on immediately to the seller of the security.

A buy/sell back is the equivalent of a "reverse repo".

Securities lending

In securities lending, the purpose is to temporarily obtain the security for other purposes, such as covering short positions or for use in complex financial structures. Securities are generally lent out for a fee and securities lending trades are governed by different types of legal agreements than repos.

Repos have traditionally been used as a form of collateralized loan and have been treated as such for tax purposes. Modern Repo agreements, however, often allow the cash lender to sell the security provided as collateral and substitute an identical security at repurchase.[15] In this way, the cash lender acts as a security borrower and the Repo agreement can be used to take a short position in the security very much like a security loan might be used.[16]

Reverse repo

A reverse repo is simply the same repurchase agreement from the buyer's viewpoint, not the seller's. Hence, the seller executing the transaction would describe it as a "repo", while the buyer in the same transaction would describe it a "reverse repo". So "repo" and "reverse repo" are exactly the same kind of transaction, just being described from opposite viewpoints. The term "reverse repo and sale" is commonly used to describe the creation of a short position in a debt instrument where the buyer in the repo transaction immediately sells the security provided by the seller on the open market. On the settlement date of the repo, the buyer acquires the relevant security on the open market and delivers it to the seller. In such a short transaction, the buyer is wagering that the relevant security will decline in value between the date of the repo and the settlement date.

Uses

For the buyer, a repo is an opportunity to invest cash for a customized period of time (other investments typically limit tenures). It is short-term and safer as a secured investment since the investor receives collateral. Market liquidity for repos is good, and rates are competitive for investors. Money Funds are large buyers of Repurchase Agreements.

For traders in trading firms, repos are used to finance long positions (in the securities they post as collateral), obtain access to cheaper funding costs for long positions in other speculative investments, and cover short positions in securities (via a "reverse repo and sale").

In addition to using repo as a funding vehicle, repo traders "make markets". These traders have been traditionally known as "matched-book repo traders". The concept of a matched-book trade follows closely to that of a broker who takes both sides of an active trade, essentially having no market risk, only credit risk. Elementary matched-book traders engage in both the repo and a reverse repo within a short period of time, capturing the profits from the bid/ask spread between the reverse repo and repo rates. Currently, matched-book repo traders employ other profit strategies, such as non-matched maturities, collateral swaps, and liquidity management.

United States Federal Reserve use of repos

When transacted by the Federal Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve in open market operations, repurchase agreements add reserves to the banking system and then after a specified period of time withdraw them; reverse repos initially drain reserves and later add them back. This tool can also be used to stabilize interest rates, and the Federal Reserve has used it to adjust the federal funds rate to match the target rate.[17]

Under a repurchase agreement, the Federal Reserve (Fed) buys U.S. Treasury securities, U.S. agency securities, or mortgage-backed securities from a primary dealer who agrees to buy them back within typically one to seven days; a reverse repo is the opposite. Thus, the Fed describes these transactions from the counterparty's viewpoint rather than from their own viewpoint.

If the Federal Reserve is one of the transacting parties, the RP is called a "system repo", but if they are trading on behalf of a customer (e.g., a foreign central bank), it is called a "customer repo". Until 2003, the Fed did not use the term "reverse repo"—which it believed implied that it was borrowing money (counter to its charter)—but used the term "matched sale" instead.

Reserve Bank of India's use of repos

In India, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) uses repo and reverse repo to increase or decrease money supply in the economy. The rate at which the RBI lends to commercial banks is called the repo rate. In case of inflation, the RBI may increase the repo rate, thus discouraging banks to borrow and reducing the money supply in the economy.[18] As of September 2020, the RBI repo rate is set at 4.00% and the reverse repo rate at 3.35%.[19]

Lehman Brothers' use of repos as a mis-classified sale

The investment bank Lehman Brothers used repos nicknamed "repo 105" and "repo 108" as a creative accounting strategy to bolster their profitability reports for a few days during reporting season, and mis-classified the repos as true sales. New York attorney general Andrew Cuomo alleged that this practice was fraudulent and happened under the watch of accounting firm Ernst & Young. Charges have been filed against E&Y, with the allegations stating that the firm approved the practice of using repos for "the surreptitious removal of tens of billions of dollars of securities from Lehman’s balance sheet in order to create a false impression of Lehman’s liquidity, thereby defrauding the investing public".[20]

In the Lehman Brothers case, repos were used as Tobashi schemes to temporarily conceal significant losses by intentionally timed, half-completed trades during the reporting season. This mis-use of repos is similar to the swaps by Goldman Sachs in the "Greek Debt Mask"[21] which were used as a Tobashi scheme to legally circumvent the Maastricht Treaty deficit rules for active European Union members and allowed Greece to "hide" more than 2.3 billion Euros of debt.[22]

Risks

While classic repos are generally credit-risk mitigated instruments, there are residual credit risks. Though it is essentially a collateralized transaction, the seller may fail to repurchase the securities sold, at the maturity date. In other words, the repo seller defaults on their obligation. Consequently, the buyer may keep the security, and liquidate the security to recover the cash lent. The security, however, may have lost value since the outset of the transaction, as the security is subject to market movements. To mitigate this risk, repos often are over-collateralized as well as being subject to daily mark-to-market margining (i.e., if the collateral falls in value, a margin call can be triggered asking the borrower to post extra securities). Conversely, if the value of the security rises there is a credit risk for the borrower in that the creditor may not sell them back. If this is considered to be a risk, then the borrower may negotiate a repo which is under-collateralized.[7]

Credit risk associated with repo is subject to many factors: term of repo, liquidity of security, the strength of the counterparties involved, etc.

Certain forms of repo transactions came into focus within the financial press due to the technicalities of settlements following the collapse of Refco in 2005. Occasionally, a party involved in a repo transaction may not have a specific bond at the end of the repo contract. This may cause a string of failures from one party to the next, for as long as different parties have transacted for the same underlying instrument. The focus of the media attention centers on attempts to mitigate these failures.

In 2008, attention was drawn to a form known as repo 105 following the Lehman collapse, as it was alleged that repo 105s had been used as an accounting trick to hide Lehman's worsening financial health. Another controversial form of repurchase order is the "internal repo" which first came to prominence in 2005. In 2011, it was suggested that repos used to finance risky trades in sovereign European bonds may have been the mechanism by which MF Global put at risk some several hundred million dollars of client funds, before its bankruptcy in October 2011. Much of the collateral for the repos is understood to have been obtained by the rehypothecation of other collateral belonging to the clients.[23][24]

During September 2019, the U.S. Federal Reserve intervened in the role of investor to provide funds in the repo markets, when overnight lending rates jumped due to a series of technical factors that had limited the supply of funds available.[1][4]

See also

- Collateral management

- Currency swap

- Discount window

- Dollar roll

- Federal funds

- Implied repo rate

- Margin (finance)

- Money market

- Official bank rate

- Total return swap

Notes and references

- Matt Phillips (18 September 2019). "Wall Street is Buzzing About Repo Rates". The New York Times.

- "Treasury Repo Reference Rates". Federal Reserve. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Gary Gorton (August 2009). "Securitized banking and the run on repo". NBER. doi:10.3386/w15223. S2CID 198184332. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Statement Regarding Monetary Policy Implementation". Federal Reserve. 11 October 2019.

- Chen, James (28 December 2020). "Reverse Repurchase Agreement". STOCK TRADING STOCK TRADING STRATEGY & EDUCATION. Investopedia. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- Lemke, Lins, Hoenig & Rube, Hedge Funds and Other Private Funds: Regulation and Compliance, §6:38 (Thomson West, 2016 ed.)

- Kenneth D. Garbade (1 May 2006). "The Evolution of Repo Contracting Conventions in the 1980s" (PDF). New York Fed. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- Wall St. Securities Firm Files For Bankruptcy New York Times 13 August 1982

- The Evolution of Repo Contracting Conventions in the 1980s FRBNY Economic Policy Review; May 2006

- "The Government Securities Market: In the Wake of ESM Santa Clara Law Review January 1, 1987".

- Darrell Duffie and Anil K Kashyap (27 July 2011). "US default would spell turmoil for the repo market". Financial Times. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Sherman, Scott (26 June 2019). "Reference Rate Production Update ARRC Meeting" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Gillian Tett (23 September 2010). "Repo needs a backstop to avoid future crises". The Financial Times. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- In other words, if the lender seeks a high rate of return they can accept securities with a relatively high risk of falling in value and so enjoy a higher repo rate, whereas if they are risk averse they can select securities which are expected to rise or at least not fall in value.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "primebrokerage.net". ww12.primebrokerage.net.

- John Hussman. "Hardly a Bailout" Hussman Funds, 13 August 2007. Accessed 3 September 2010.

- "Definition of 'Repo Rate'". The Economic Times. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- Das, Saikat. "RBI unlikely to change repo rate this week". The Economic Times. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- "E&Y sued over Lehmans audit". Accountancy Age. 21 December 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Balzli, Beat (8 February 2010). "Greek Debt Crisis: How Goldman Sachs Helped Greece to Mask its True Debt". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- "Goldman Sachs details 2001 Greek derivative trades". Reuters. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- AZAM AHMED and BEN PROTESS (3 November 2011). "As Regulators Pressed Changes, Corzine Pushed Back, and Won". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "Rehypothecation revisited". ftseglobalmarket.com. 19 March 2013. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- McCormick, Liz Capo; Alexandra Harris (11 September 2019). "Decade After Repos Hastened Lehman's Fall, the Coast Isn't Clear". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

External links

- Baklanova, Viktoria; Copeland, Adam; McCaughrin, Rebecca (September 2015), "Reference Guide to U.S. Repo and Securities Lending Markets" (PDF), Staff Reports, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, no. 740

- Repurchase and Reverse Repurchase Transactions – Fedpoints – Federal Reserve Bank of New York

- Explanation of the Federal Reserve repurchase agreements actions of August 10, 2007

- Statement Regarding Counterparties for Reverse Repurchase Agreements March 8, 2010