Rings of Uranus

The rings of Uranus are intermediate in complexity between the more extensive set around Saturn and the simpler systems around Jupiter and Neptune. The rings of Uranus were discovered on March 10, 1977, by James L. Elliot, Edward W. Dunham, and Jessica Mink. William Herschel had also reported observing rings in 1789; modern astronomers are divided on whether he could have seen them, as they are very dark and faint.[1]

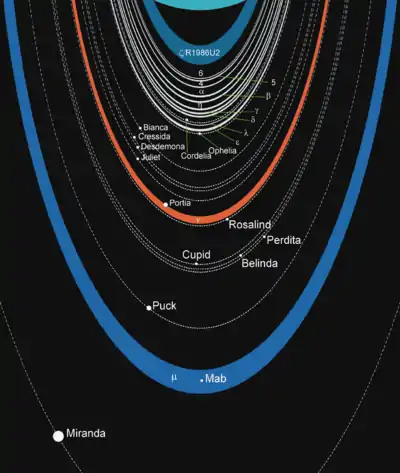

By 1977, nine distinct rings were identified. Two additional rings were discovered in 1986 in images taken by the Voyager 2 spacecraft, and two outer rings were found in 2003–2005 in Hubble Space Telescope photos. In the order of increasing distance from the planet the 13 known rings are designated 1986U2R/ζ, 6, 5, 4, α, β, η, γ, δ, λ, ε, ν and μ. Their radii range from about 38,000 km for the 1986U2R/ζ ring to about 98,000 km for the μ ring. Additional faint dust bands and incomplete arcs may exist between the main rings. The rings are extremely dark—the Bond albedo of the rings' particles does not exceed 2%. They are probably composed of water ice with the addition of some dark radiation-processed organics.

The majority of Uranus's rings are opaque and only a few kilometres wide. The ring system contains little dust overall; it consists mostly of large bodies 20 cm to 20 m in diameter. Some rings are optically thin: the broad and faint 1986U2R/ζ, μ and ν rings are made of small dust particles, while the narrow and faint λ ring also contains larger bodies. The relative lack of dust in the ring system may be due to aerodynamic drag from the extended Uranian exosphere.

The rings of Uranus are thought to be relatively young, and not more than 600 million years old. The Uranian ring system probably originated from the collisional fragmentation of several moons that once existed around the planet. After colliding, the moons probably broke up into many particles, which survived as narrow and optically dense rings only in strictly confined zones of maximum stability.

The mechanism that confines the narrow rings is not well understood. Initially it was assumed that every narrow ring had a pair of nearby shepherd moons corralling it into shape. In 1986 'Voyager 2' discovered only one such shepherd pair (Cordelia and Ophelia) around the brightest ring (ε), though the faint ν would later be discovered shepherded between Portia and Rosalind.[2]

Discovery

The first mention of a Uranian ring system comes from William Herschel's notes detailing his observations of Uranus in the 18th century, which include the following passage: "February 22, 1789: A ring was suspected".[1] Herschel drew a small diagram of the ring and noted that it was "a little inclined to the red". The Keck Telescope in Hawaii has since confirmed this to be the case, at least for the ν ring.[3] Herschel's notes were published in a Royal Society journal in 1797. In the two centuries between 1797 and 1977 the rings are rarely mentioned, if at all. This casts serious doubt on whether Herschel could have seen anything of the sort while hundreds of other astronomers saw nothing. It has been claimed that Herschel gave accurate descriptions of the ε ring's size relative to Uranus, its changes as Uranus travelled around the Sun, and its color.[4]

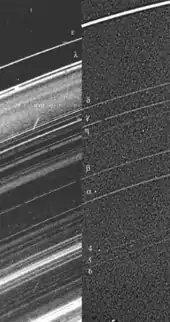

The definitive discovery of the Uranian rings was made by astronomers James L. Elliot, Edward W. Dunham, and Jessica Mink on March 10, 1977, using the Kuiper Airborne Observatory, and was serendipitous. They planned to use the occultation of the star SAO 158687 by Uranus to study the planet's atmosphere. When their observations were analysed, they found that the star disappeared briefly from view five times both before and after it was eclipsed by the planet. They deduced that a system of narrow rings was present.[5][6] The five occultation events they observed were denoted by the Greek letters α, β, γ, δ and ε in their papers.[5] These designations have been used as the rings' names since then. Later they found four additional rings: one between the β and γ rings and three inside the α ring.[7] The former was named the η ring. The latter were dubbed rings 4, 5 and 6—according to the numbering of the occultation events in one paper.[8] Uranus's ring system was the second to be discovered in the Solar System, after that of Saturn.[9]

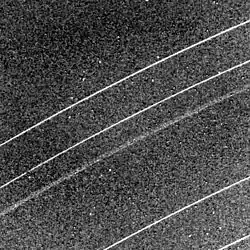

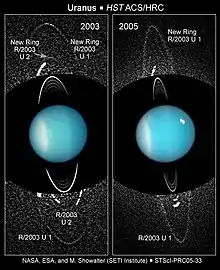

The rings were directly imaged when the Voyager 2 spacecraft flew through the Uranian system in 1986.[10] Two more faint rings were revealed, bringing the total to eleven.[10] The Hubble Space Telescope detected an additional pair of previously unseen rings in 2003–2005, bringing the total number known to 13. The discovery of these outer rings doubled the known radius of the ring system.[11] Hubble also imaged two small satellites for the first time, one of which, Mab, shares its orbit with the outermost newly discovered μ ring.[12]

General properties

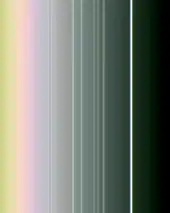

As currently understood, the ring system of Uranus comprises thirteen distinct rings. In order of increasing distance from the planet they are: 1986U2R/ζ, 6, 5, 4, α, β, η, γ, δ, λ, ε, ν, μ rings.[11] They can be divided into three groups: nine narrow main rings (6, 5, 4, α, β, η, γ, δ, ε),[9] two dusty rings (1986U2R/ζ, λ)[13] and two outer rings (ν, μ).[11][14] The rings of Uranus consist mainly of macroscopic particles and little dust,[15] although dust is known to be present in 1986U2R/ζ, η, δ, λ, ν and μ rings.[11][13] In addition to these well-known rings, there may be numerous optically thin dust bands and faint rings between them.[16] These faint rings and dust bands may exist only temporarily or consist of a number of separate arcs, which are sometimes detected during occultations.[16] Some of them became visible during a series of ring plane-crossing events in 2007.[17] A number of dust bands between the rings were observed in forward-scattering[lower-alpha 1] geometry by Voyager 2.[10] All rings of Uranus show azimuthal brightness variations.[10]

The rings are made of an extremely dark material. The geometric albedo of the ring particles does not exceed 5–6%, while the Bond albedo is even lower—about 2%.[15][18] The rings particles demonstrate a steep opposition surge—an increase of the albedo when the phase angle is close to zero.[15] This means that their albedo is much lower when they are observed slightly off the opposition.[lower-alpha 2] The rings are slightly red in the ultraviolet and visible parts of the spectrum and grey in near-infrared.[19] They exhibit no identifiable spectral features. The chemical composition of the ring particles is not known. They cannot be made of pure water ice like the rings of Saturn because they are too dark, darker than the inner moons of Uranus.[19] This indicates that they are probably composed of a mixture of the ice and a dark material. The nature of this material is not clear, but it may be organic compounds considerably darkened by the charged particle irradiation from the Uranian magnetosphere. The rings' particles may consist of a heavily processed material which was initially similar to that of the inner moons.[19]

As a whole, the ring system of Uranus is unlike either the faint dusty rings of Jupiter or the broad and complex rings of Saturn, some of which are composed of very bright material—water ice.[9] There are similarities with some parts of the latter ring system; the Saturnian F ring and the Uranian ε ring are both narrow, relatively dark and are shepherded by a pair of moons.[9] The newly discovered outer ν and μ rings of Uranus are similar to the outer G and E rings of Saturn.[20] Narrow ringlets existing in the broad Saturnian rings also resemble the narrow rings of Uranus.[9] In addition, dust bands observed between the main rings of Uranus may be similar to the rings of Jupiter.[13] In contrast, the Neptunian ring system is quite similar to that of Uranus, although it is less complex, darker and contains more dust; the Neptunian rings are also positioned further from the planet.[13]

Narrow main rings

ε ring

The ε ring is the brightest and densest part of the Uranian ring system, and is responsible for about two-thirds of the light reflected by the rings.[10][19] While it is the most eccentric of the Uranian rings, it has negligible orbital inclination.[21] The ring's eccentricity causes its brightness to vary over the course of its orbit. The radially integrated brightness of the ε ring is highest near apoapsis and lowest near periapsis.[22] The maximum/minimum brightness ratio is about 2.5–3.0.[15] These variations are connected with the variations of the ring width, which is 19.7 km at the periapsis and 96.4 km at the apoapsis.[22] As the ring becomes wider, the amount of shadowing between particles decreases and more of them come into view, leading to higher integrated brightness.[18] The width variations were measured directly from Voyager 2 images, as the ε ring was one of only two rings resolved by Voyager's cameras.[10] Such behavior indicates that the ring is not optically thin. Indeed, occultation observations conducted from the ground and the spacecraft showed that its normal optical depth[lower-alpha 3] varies between 0.5 and 2.5,[22][23] being highest near the periapsis. The equivalent depth[lower-alpha 4] of the ε ring is around 47 km and is invariant around the orbit.[22]

The geometric thickness of the ε ring is not precisely known, although the ring is certainly very thin—by some estimates as thin as 150 m.[16] Despite such infinitesimal thickness, it consists of several layers of particles. The ε ring is a rather crowded place with a filling factor near the apoapsis estimated by different sources at from 0.008 to 0.06.[22] The mean size of the ring particles is 0.2–20.0 m,[16] and the mean separation is around 4.5 times their radius.[22] The ring is almost devoid of dust, possibly due to the aerodynamic drag from Uranus's extended atmospheric corona.[3] Due to its razor-thin nature the ε ring is invisible when viewed edge-on. This happened in 2007 when a ring plane-crossing was observed.[17]

The Voyager 2 spacecraft observed a strange signal from the ε ring during the radio occultation experiment.[23] The signal looked like a strong enhancement of the forward-scattering at the wavelength 3.6 cm near ring's apoapsis. Such strong scattering requires the existence of a coherent structure. That the ε ring does have such a fine structure has been confirmed by many occultation observations.[16] The ε ring seems to consist of a number of narrow and optically dense ringlets, some of which may have incomplete arcs.[16]

The ε ring is known to have interior and exterior shepherd moons—Cordelia and Ophelia, respectively.[24] The inner edge of the ring is in 24:25 resonance with Cordelia, and the outer edge is in 14:13 resonance with Ophelia.[24] The masses of the moons need to be at least three times the mass of the ring to confine it effectively.[9] The mass of the ε ring is estimated to be about 1016 kg.[9][24]

δ ring

The δ ring is circular and slightly inclined.[21] It shows significant unexplained azimuthal variations in normal optical depth and width.[16] One possible explanation is that the ring has an azimuthal wave-like structure, excited by a small moonlet just inside it.[25] The sharp outer edge of the δ ring is in 23:22 resonance with Cordelia.[26] The δ ring consists of two components: a narrow optically dense component and a broad inward shoulder with low optical depth.[16] The width of the narrow component is 4.1–6.1 km and the equivalent depth is about 2.2 km, which corresponds to a normal optical depth of about 0.3–0.6.[22] The ring's broad component is about 10–12 km wide and its equivalent depth is close to 0.3 km, indicating a low normal optical depth of 3 × 10−2.[22][27] This is known only from occultation data because Voyager 2's imaging experiment failed to resolve the δ ring.[10][27] When observed in forward-scattering geometry by Voyager 2, the δ ring appeared relatively bright, which is compatible with the presence of dust in its broad component.[10] The broad component is geometrically thicker than the narrow component. This is supported by the observations of a ring plane-crossing event in 2007, when the δ ring remained visible, which is consistent with the behavior of a simultaneously geometrically thick and optically thin ring.[17]

γ ring

The γ ring is narrow, optically dense and slightly eccentric. Its orbital inclination is almost zero.[21] The width of the ring varies in the range 3.6–4.7 km, although equivalent optical depth is constant at 3.3 km.[22] The normal optical depth of the γ ring is 0.7–0.9. During a ring plane-crossing event in 2007 the γ ring disappeared, which means it is geometrically thin like the ε ring[16] and devoid of dust.[17] The width and normal optical depth of the γ ring show significant azimuthal variations.[16] The mechanism of confinement of such a narrow ring is not known, but it has been noticed that the sharp inner edge of the γ ring is in a 6:5 resonance with Ophelia.[26][28]

η ring

The η ring has zero orbital eccentricity and inclination.[21] Like the δ ring, it consists of two components: a narrow optically dense component and a broad outward shoulder with low optical depth.[10] The width of the narrow component is 1.9–2.7 km and the equivalent depth is about 0.42 km, which corresponds to the normal optical depth of about 0.16–0.25.[22] The broad component is about 40 km wide and its equivalent depth is close to 0.85 km, indicating a low normal optical depth of 2 × 10−2.[22] It was resolved in Voyager 2 images.[10] In forward-scattered light, the η ring looked bright, which indicated the presence of a considerable amount of dust in this ring, probably in the broad component.[10] The broad component is much thicker (geometrically) than the narrow one. This conclusion is supported by the observations of a ring plane-crossing event in 2007, when the η ring demonstrated increased brightness, becoming the second brightest feature in the ring system.[17] This is consistent with the behavior of a geometrically thick but simultaneously optically thin ring.[17] Like the majority of other rings, the η ring shows significant azimuthal variations in the normal optical depth and width. The narrow component even vanishes in some places.[16]

α and β rings

After the ε ring, the α and β rings are the brightest of Uranus's rings.[15] Like the ε ring, they exhibit regular variations in brightness and width.[15] They are brightest and widest 30° from the apoapsis and dimmest and narrowest 30° from the periapsis.[10][29] The α and β rings have sizable orbital eccentricity and non-negligible inclination.[21] The widths of these rings are 4.8–10 km and 6.1–11.4 km, respectively.[22] The equivalent optical depths are 3.29 km and 2.14 km, resulting in normal optical depths of 0.3–0.7 and 0.2–0.35, respectively.[22] During a ring plane-crossing event in 2007 the rings disappeared, which means they are geometrically thin like the ε ring and devoid of dust.[17] The same event revealed a thick and optically thin dust band just outside the β ring, which was also observed earlier by Voyager 2.[10] The masses of the α and β rings are estimated to be about 5 × 1015 kg (each)—half the mass of the ε ring.[30]

Rings 6, 5 and 4

Rings 6, 5 and 4 are the innermost and dimmest of Uranus's narrow rings.[15] They are the most inclined rings, and their orbital eccentricities are the largest excluding the ε ring.[21] In fact, their inclinations (0.06°, 0.05° and 0.03°) were large enough for Voyager 2 to observe their elevations above the Uranian equatorial plane, which were 24–46 km.[10] Rings 6, 5 and 4 are also the narrowest rings of Uranus, measuring 1.6–2.2 km, 1.9–4.9 km and 2.4–4.4 km wide, respectively.[10][22] Their equivalent depths are 0.41 km, 0.91 and 0.71 km resulting in normal optical depth 0.18–0.25, 0.18–0.48 and 0.16–0.3.[22] They were not visible during a ring plane-crossing event in 2007 due to their narrowness and lack of dust.[17]

Dusty rings

λ ring

The λ ring was one of two rings discovered by Voyager 2 in 1986.[21] It is a narrow, faint ring located just inside the ε ring, between it and the shepherd moon Cordelia.[10] This moon clears a dark lane just inside the λ ring. When viewed in back-scattered light,[lower-alpha 5] the λ ring is extremely narrow—about 1–2 km—and has the equivalent optical depth 0.1–0.2 km at the wavelength 2.2 μm.[3] The normal optical depth is 0.1–0.2.[10][27] The optical depth of the λ ring shows strong wavelength dependence, which is atypical for the Uranian ring system. The equivalent depth is as high as 0.36 km in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum, which explains why λ ring was initially detected only in UV stellar occultations by Voyager 2.[27] The detection during a stellar occultation at the wavelength 2.2 μm was only announced in 1996.[3]

The appearance of the λ ring changed dramatically when it was observed in forward-scattered light in 1986.[10] In this geometry the ring became the brightest feature of the Uranian ring system, outshining the ε ring.[13] This observation, together with the wavelength dependence of the optical depth, indicates that the λ ring contains significant amount of micrometre-sized dust.[13] The normal optical depth of this dust is 10−4–10−3.[15] Observations in 2007 by the Keck telescope during the ring plane-crossing event confirmed this conclusion, because the λ ring became one of the brightest features in the Uranian ring system.[17]

Detailed analysis of the Voyager 2 images revealed azimuthal variations in the brightness of the λ ring.[15] The variations appear to be periodic, resembling a standing wave. The origin of this fine structure in the λ ring remains a mystery.[13]

1986U2R/ζ ring

In 1986 Voyager 2 detected a broad and faint sheet of material inward of ring 6.[10] This ring was given the temporary designation 1986U2R. It had a normal optical depth of 10−3 or less and was extremely faint. It was visible only in a single Voyager 2 image.[10] The ring was located between 37,000 and 39,500 km from the centre of Uranus, or only about 12,000 km above the clouds.[3] It was not observed again until 2003–2004, when the Keck telescope found a broad and faint sheet of material just inside ring 6. This ring was dubbed the ζ ring.[3] The position of the recovered ζ ring differs significantly from that observed in 1986. Now it is situated between 37,850 and 41,350 km from the centre of the planet. There is an inward gradually fading extension reaching to at least 32,600 km,[3] or possibly even to 27,000 km—to the atmosphere of Uranus. These extensions are labelled as the ζc and ζcc rings respectively.[31]

The ζ ring was observed again during the ring plane-crossing event in 2007 when it became the brightest feature of the ring system, outshining all other rings combined.[17] The equivalent optical depth of this ring is near 1 km (0.6 km for the inward extension), while the normal optical depth is again less than 10−3.[3] Rather different appearances of the 1986U2R and ζ rings may be caused by different viewing geometries: back-scattering geometry in 2003–2007 and side-scattering geometry in 1986.[3][17] Changes during the past 20 years in the distribution of dust, which is thought to predominate in the ring, cannot be ruled out.[17]

Other dust bands

In addition to the 1986U2R/ζ and λ rings, there are other extremely faint dust bands in the Uranian ring system.[10] They are invisible during occultations because they have negligible optical depth, though they are bright in forward-scattered light.[13] Voyager 2's images of forward-scattered light revealed the existence of bright dust bands between the λ and δ rings, between the η and β rings, and between the α ring and ring 4.[10] Many of these bands were detected again in 2003–2004 by the Keck Telescope and during the 2007 ring-plane crossing event in backscattered light, but their precise locations and relative brightnesses were different from during the Voyager observations.[3][17] The normal optical depth of the dust bands is about 10−5 or less. The dust particle size distribution is thought to obey a power law with the index p = 2.5 ± 0.5.[15]

In addition to separate dust bands the system of Uranian rings appears to be immersed into wide and faint sheet of dust with the normal optical depth not exceeding 10−3.[31]

Outer ring system

In 2003–2005, the Hubble Space Telescope detected a pair of previously unknown rings, now called the outer ring system, which brought the number of known Uranian rings to 13.[11] These rings were subsequently named the μ and ν rings.[14] The μ ring is the outermost of the pair, and is twice the distance from the planet as the bright η ring.[11] The outer rings differ from the inner narrow rings in a number of respects. They are broad, 17,000 and 3,800 km wide, respectively, and very faint. Their peak normal optical depths are 8.5 × 10−6 and 5.4 × 10−6, respectively. The resulting equivalent optical depths are 0.14 km and 0.012 km. The rings have triangular radial brightness profiles.[11]

The peak brightness of the μ ring lies almost exactly on the orbit of the small Uranian moon Mab, which is probably the source of the ring’s particles.[11][12] The ν ring is positioned between Portia and Rosalind and does not contain any moons inside it.[11] A reanalysis of the Voyager 2 images of forward-scattered light clearly reveals the μ and ν rings. In this geometry the rings are much brighter, which indicates that they contain much micrometer-sized dust.[11] The outer rings of Uranus may be similar to the G and E rings of Saturn as E ring is extremely broad and receives dust from Enceladus.[11][12]

The μ ring may consist entirely of dust, without any large particles at all. This hypothesis is supported by observations performed by the Keck telescope, which failed to detect the μ ring in the near infrared at 2.2 μm, but detected the ν ring.[20] This failure means that the μ ring is blue in color, which in turn indicates that very small (submicrometer) dust predominates within it.[20] The dust may be made of water ice.[32] In contrast, the ν ring is slightly red in color.[20][33]

Dynamics and origin

An outstanding problem concerning the physics governing the narrow Uranian rings is their confinement. Without some mechanism to hold their particles together, the rings would quickly spread out radially.[9] The lifetime of the Uranian rings without such a mechanism cannot be more than 1 million years.[9] The most widely cited model for such confinement, proposed initially by Goldreich and Tremaine,[34] is that a pair of nearby moons, outer and inner shepherds, interact gravitationally with a ring and act like sinks and donors, respectively, for excessive and insufficient angular momentum (or equivalently, energy). The shepherds thus keep ring particles in place, but gradually move away from the ring themselves.[9] To be effective, the masses of the shepherds should exceed the mass of the ring by at least a factor of two to three. This mechanism is known to be at work in the case of the ε ring, where Cordelia and Ophelia serve as shepherds.[26] Cordelia is also the outer shepherd of the δ ring, and Ophelia is the outer shepherd of the γ ring.[26] No moon larger than 10 km is known in the vicinity of other rings.[10] The current distance of Cordelia and Ophelia from the ε ring can be used to estimate the ring’s age. The calculations show that the ε ring cannot be older than 600 million years.[9][24]

Since the rings of Uranus appear to be young, they must be continuously renewed by the collisional fragmentation of larger bodies.[9] The estimates show that the lifetime against collisional disruption of a moon with the size like that of Puck is a few billion years. The lifetime of a smaller satellite is much shorter.[9] Therefore, all current inner moons and rings can be products of disruption of several Puck-sized satellites during the last four and half billion years.[24] Every such disruption would have started a collisional cascade that quickly ground almost all large bodies into much smaller particles, including dust.[9] Eventually the majority of mass was lost, and particles survived only in positions that were stabilized by mutual resonances and shepherding. The end product of such a disruptive evolution would be a system of narrow rings. A few moonlets must still be embedded within the rings at present. The maximum size of such moonlets is probably around 10 km.[24]

The origin of the dust bands is less problematic. The dust has a very short lifetime, 100–1000 years, and should be continuously replenished by collisions between larger ring particles, moonlets and meteoroids from outside the Uranian system.[13][24] The belts of the parent moonlets and particles are themselves invisible due to their low optical depth, while the dust reveals itself in forward-scattered light.[24] The narrow main rings and the moonlet belts that create dust bands are expected to differ in particle size distribution. The main rings have more centimeter to meter-sized bodies. Such a distribution increases the surface area of the material in the rings, leading to high optical density in back-scattered light.[24] In contrast, the dust bands have relatively few large particles, which results in low optical depth.[24]

Exploration

The rings were thoroughly investigated by the Voyager 2 spacecraft in January 1986.[21] Two new faint rings—λ and 1986U2R—were discovered bringing the total number then known to eleven. Rings were studied by analyzing results of radio,[23] ultraviolet[27] and optical occultations.[16] Voyager 2 observed the rings in different geometries relative to the sun, producing images with back-scattered, forward-scattered and side-scattered light.[10] Analysis of these images allowed derivation of the complete phase function, geometrical and Bond albedo of ring particles.[15] Two rings—ε and η—were resolved in the images revealing a complicated fine structure.[10] Analysis of Voyager's images also led to discovery of eleven inner moons of Uranus, including the two shepherd moons of the ε ring—Cordelia and Ophelia.[10]

List of properties

This table summarizes the properties of the planetary ring system of Uranus.

| Ring name | Radius (km)[lower-alpha 6] | Width (km)[lower-alpha 6] | Eq. depth (km)[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 7] | N. Opt. depth[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 8] | Thickness (m)[lower-alpha 9] | Ecc.[lower-alpha 10] | Incl.(°)[lower-alpha 10] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ζcc | 26 840–34 890 | 8 000 | 0.8 | ~ 0.001 | ? | ? | ? | Inward extension of the ζc ring |

| ζc | 34 890–37 850 | 3 000 | 0.6 | ~ 0.01 | ? | ? | ? | Inward extension of the ζ ring |

| 1986U2R | 37 000–39 500 | 2 500 | <2.5 | < 0.01 | ? | ? | ? | Faint dusty ring |

| ζ | 37 850–41 350 | 3 500 | 1 | ~ 0.01 | ? | ? | ? | |

| 6 | 41 837 | 1.6–2.2 | 0.41 | 0.18–0.25 | ? | 0.0010 | 0.062 | |

| 5 | 42 234 | 1.9–4.9 | 0.91 | 0.18–0.48 | ? | 0.0019 | 0.054 | |

| 4 | 42 570 | 2.4–4.4 | 0.71 | 0.16–0.30 | ? | 0.0011 | 0.032 | |

| α | 44 718 | 4.8–10.0 | 3.39 | 0.3–0.7 | ? | 0.0008 | 0.015 | |

| β | 45 661 | 6.1–11.4 | 2.14 | 0.20–0.35 | ? | 0.0040 | 0.005 | |

| η | 47 175 | 1.9–2.7 | 0.42 | 0.16–0.25 | ? | 0 | 0.001 | |

| ηc | 47 176 | 40 | 0.85 | 0.2 | ? | 0 | 0.001 | Outward broad component of the η ring |

| γ | 47 627 | 3.6–4.7 | 3.3 | 0.7–0.9 | 150? | 0.001 | 0.002 | |

| δc | 48 300 | 10–12 | 0.3 | 0.3 | ? | 0 | 0.001 | Inward broad component of the δ ring |

| δ | 48 300 | 4.1–6.1 | 2.2 | 0.3–0.6 | ? | 0 | 0.001 | |

| λ | 50 023 | 1–2 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.2 | ? | 0? | 0? | Faint dusty ring |

| ε | 51 149 | 19.7–96.4 | 47 | 0.5–2.5 | 150? | 0.0079 | 0 | Shepherded by Cordelia and Ophelia |

| ν | 66 100–69 900 | 3 800 | 0.012 | 0.000054 | ? | ? | ? | Between Portia and Rosalind, peak brightness at 67 300 km |

| μ | 86 000–103 000 | 17 000 | 0.14 | 0.000085 | ? | ? | ? | At Mab, peak brightness at 97 700 km |

Notes

- Forward-scattered light is the light scattered at a small angle relative to the solar light (phase angle close to 180°).

- Off opposition means that the angle between the object-sun direction and object-Earth direction is not zero.

- The normal optical depth τ of a ring is the ratio of the total geometrical cross-section of the ring's particles to the square area of the ring. It assumes values from zero to infinity. A light beam passing normally through a ring will be attenuated by the factor e−τ.[15]

- The equivalent depth ED of a ring is defined as an integral of the normal optical depth across the ring. In other words ED=∫τdr, where r is radius.[3]

- Back-scattered light is the light scattered at an angle close to 180° relative to the solar light (phase angle close to 0°).

- The radii of the 6,5,4, α, β, η, γ, δ, λ and ε rings were taken from Esposito et al., 2002.[9] The widths of the 6,5,4, α, β, η, γ, δ and ε rings are from Karkoshka et al., 2001.[22] The radii and widths of the ζ and 1986U2R rings were taken from de Pater et al., 2006.[3] The width of the λ ring is from Holberg et al., 1987.[27] The radii and widths of the μ and ν rings were extracted from Showalter et al., 2006.[11]

- The equivalent depth of the 1986U2R and ζc/ζcc rings is a product of their width and the normal optical depth. The equivalent depths of the 6,5,4, α, β, η, γ, δ and ε rings were taken from Karkoshka et al., 2001.[22] The equivalent depths of the λ and ζ, μ and ν rings are derived using μEW values from de Pater et al., 2006[3] and de Pater et al., 2006b,[20] respectively. The μEW values for these rings were multiplied by the factor 20, which corresponds to the assumed albedo of the ring's particles of 5%.

- The normal optical depths of all rings except ζ, ζc, ζcc, 1986U2R, μ and ν were calculated as ratios of the equivalent depths to the widths. The normal optical depth of the 1986U2R ring was taken from de Smith et al., 1986.[10] The normal optical depths of the μ and ν rings are peak values from Showalter et al., 2006,[11] while the normal optical depths of ζ, ζc and ζcc rings are from Dunn eta al., 2010.[31]

- The thickness estimates are from Lane et al., 1986.[16]

- The rings' eccentricities and inclinations were taken from Stone et al., 1986 and French et al., 1989.[21][28]

References

- Rincon, Paul (Apr 18, 2007). "Uranus rings 'were seen in 1700s'". BBC News. Retrieved 23 January 2012.(re study by Stuart Eves)

- Filacchione & Ciarniello (2021) "Rings", Encyclopedia of Geology, 2nd edition, INAF-IAPS, Rome

- de Pater, Imke; Gibbard, Seran G.; Hammel, H.B. (2006). "Evolution of the dusty rings of Uranus". Icarus. 180 (1): 186–200. Bibcode:2006Icar..180..186D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.08.011.

- "Did William Herschel Discover The Rings Of Uranus In The 18th Century?". Physorg.com. 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- Elliot, J.L.; Dunham, E; Mink, D. (1977). "The Occultation of SAO – 15 86687 by the Uranian Satellite Belt". International Astronomical Union, Circular No. 3051.

- Elliot, J.L.; Dunham, E.; Mink, D. (1977). "The rings of Uranus". Nature. 267 (5609): 328–330. Bibcode:1977Natur.267..328E. doi:10.1038/267328a0. S2CID 4194104.

- Nicholson, P. D.; Persson, S.E.; Matthews, K.; et al. (1978). "The Rings of Uranus: Results from 10 April 1978 Occultations" (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. 83: 1240–1248. Bibcode:1978AJ.....83.1240N. doi:10.1086/112318.

- Millis, R.L.; Wasserman, L.H. (1978). "The Occultation of BD −15 3969 by the Rings of Uranus". The Astronomical Journal. 83: 993–998. Bibcode:1978AJ.....83..993M. doi:10.1086/112281.

- Esposito, L. W. (2002). "Planetary rings". Reports on Progress in Physics. 65 (12): 1741–1783. Bibcode:2002RPPh...65.1741E. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/65/12/201. S2CID 250909885.

- Smith, B. A.; Soderblom, L. A.; Beebe, A.; Bliss, D.; Boyce, J. M.; Brahic, A.; Briggs, G. A.; Brown, R. H.; Collins, S. A. (4 July 1986). "Voyager 2 in the Uranian System: Imaging Science Results". Science (Submitted manuscript). 233 (4759): 43–64. Bibcode:1986Sci...233...43S. doi:10.1126/science.233.4759.43. PMID 17812889. S2CID 5895824.

- Showalter, Mark R.; Lissauer, Jack J. (2006-02-17). "The Second Ring-Moon System of Uranus: Discovery and Dynamics". Science. 311 (5763): 973–977. Bibcode:2006Sci...311..973S. doi:10.1126/science.1122882. PMID 16373533. S2CID 13240973.

- "NASA's Hubble Discovers New Rings and Moons Around Uranus". Hubblesite. 2005. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- Burns, J.A.; Hamilton, D.P.; Showalter, M.R. (2001). "Dusty Rings and Circumplanetary Dust: Observations and Simple Physics" (PDF). In Grun, E.; Gustafson, B. A. S.; Dermott, S. T.; Fechtig H. (eds.). Interplanetary Dust. Berlin: Springer. pp. 641–725.

- Showalter, Mark R.; Lissauer, J. J.; French, R. G.; et al. (2008). "The Outer Dust Rings of Uranus in the Hubble Space Telescope". AAA/Division of Dynamical Astronomy Meeting #39. 39: 16.02. Bibcode:2008DDA....39.1602S.

- Ockert, M. E.; Cuzzi, J. N.; Porco, C. C.; Johnson, T. V. (1987). "Uranian ring photometry: Results from Voyager 2". Journal of Geophysical Research. 92 (A13): 14, 969–78. Bibcode:1987JGR....9214969O. doi:10.1029/JA092iA13p14969.

- Lane, Arthur L.; Hord, Charles W.; West, Robert A.; et al. (1986). "Photometry from Voyager 2: Initial results from the uranian atmosphere, satellites and rings". Science. 233 (4759): 65–69. Bibcode:1986Sci...233...65L. doi:10.1126/science.233.4759.65. PMID 17812890. S2CID 3108775.

- de Pater, Imke; Hammel, H. B.; Showalter, Mark R.; Van Dam, Marcos A. (2007). "The Dark Side of the Rings of Uranus" (PDF). Science. 317 (5846): 1888–1890. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1888D. doi:10.1126/science.1148103. PMID 17717152. S2CID 23875293. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-03.

- Karkoshka, Erich (1997). "Rings and Satellites of Uranus: Colorful and Not So Dark". Icarus. 125 (2): 348–363. Bibcode:1997Icar..125..348K. doi:10.1006/icar.1996.5631.

- Baines, Kevin H.; Yanamandra-Fisher, Padmavati A.; Lebofsky, Larry A.; et al. (1998). "Near-Infrared Absolute Photometric Imaging of the Uranian System" (PDF). Icarus. 132 (2): 266–284. Bibcode:1998Icar..132..266B. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.5894.

- dePater, Imke; Hammel, Heidi B.; Gibbard, Seran G.; Showalter, Mark R. (2006). "New Dust Belts of Uranus: One Ring, Two Ring, Red Ring, Blue Ring" (PDF). Science. 312 (5770): 92–94. Bibcode:2006Sci...312...92D. doi:10.1126/science.1125110. OSTI 957162. PMID 16601188. S2CID 32250745. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-03.

- Stone, E.C.; Miner, E.D. (1986). "Voyager 2 encounter with the uranian system". Science. 233 (4759): 39–43. Bibcode:1986Sci...233...39S. doi:10.1126/science.233.4759.39. PMID 17812888. S2CID 32861151.

- Karkoshka, Erich (2001). "Photometric Modeling of the Epsilon Ring of Uranus and Its Spacing of Particles". Icarus. 151 (1): 78–83. Bibcode:2001Icar..151...78K. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6598.

- Tyler, J.L.; Sweetnam, D.N.; Anderson, J.D.; et al. (1986). "Voyger 2 Radio Science Observations of the Uranian System: Atmosphere, Rings, and Satellites". Science. 233 (4759): 79–84. Bibcode:1986Sci...233...79T. doi:10.1126/science.233.4759.79. PMID 17812893. S2CID 1374796.

- Esposito, L.W.; Colwell, Joshua E. (1989). "Creation of The Uranus Rings and Dust bands". Nature. 339 (6226): 605–607. Bibcode:1989Natur.339..605E. doi:10.1038/339605a0. S2CID 4270349.

- Horn, L.J.; Lane, A.L.; Yanamandra-Fisher, P. A.; Esposito, L. W. (1988). "Physical properties of Uranian delta ring from a possible density wave". Icarus. 76 (3): 485–492. Bibcode:1988Icar...76..485H. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90016-4.

- Porco, Carolyn, C.; Goldreich, Peter (1987). "Shepherding of the Uranian rings I: Kinematics". The Astronomical Journal. 93: 724–778. Bibcode:1987AJ.....93..724P. doi:10.1086/114354.

- Holberg, J.B.; Nicholson, P. D.; French, R.G.; Elliot, J.L. (1987). "Stellar Occultation probes of the Uranian Rings at 0.1 and 2.2 μm: A comparison of Voyager UVS and Earth based results". The Astronomical Journal. 94: 178–188. Bibcode:1987AJ.....94..178H. doi:10.1086/114462.

- French, Richard D.; Elliot, J.L.; French, Linda M.; et al. (1988). "Uranian Ring Orbits from Earth-based and Voyager Occultation Observations". Icarus. 73 (2): 349–478. Bibcode:1988Icar...73..349F. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90104-2.

- Gibbard, S.G.; De Pater, I.; Hammel, H.B. (2005). "Near-infrared adaptive optics imaging of the satellites and individual rings of Uranus". Icarus. 174 (1): 253–262. Bibcode:2005Icar..174..253G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.09.008.

- Chiang, Eugene I.; Culter, Christopher J. (2003). "Three-Dimensional Dynamics of Narrow Planetary Rings". The Astrophysical Journal. 599 (1): 675–685. arXiv:astro-ph/0309248. Bibcode:2003ApJ...599..675C. doi:10.1086/379151. S2CID 5103017.

- Dunn, D. E.; De Pater, I.; Stam, D. (2010). "Modeling the uranian rings at 2.2μm: Comparison with Keck AO data from July 2004". Icarus. 208 (2): 927–937. Bibcode:2010Icar..208..927D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.03.027.

- Stephen Battersby (2006). "Blue ring of Uranus linked to sparkling ice". NewScientistSpace. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- Sanders, Robert (2006-04-06). "Blue ring discovered around Uranus". UC Berkeley News. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- Goldreich, Peter; Tremaine, Scott (1979). "Towards a theory for the uranian rings". Nature. 277 (5692): 97–99. Bibcode:1979Natur.277...97G. doi:10.1038/277097a0. S2CID 4232962.

External links

- Uranus' Rings by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Uranus Rings Fact Sheet

- Hubble Discovers Giant Rings and New Moons Encircling Uranus – Hubble Space Telescope news release (22 December 2005)

- Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature – Ring and Ring Gap Nomenclature (Uranus), USGS

_-_JPEG_converted.jpg.webp)