Rock hyrax

The rock hyrax (/ˈhaɪ.ræks/; Procavia capensis), also called dassie, Cape hyrax, rock rabbit, and (in the King James Bible) coney, is a medium-sized terrestrial mammal native to Africa and the Middle East. Commonly referred to in South Africa as the dassie (IPA: [dasiː]; Afrikaans: klipdassie),[3] it is one of the five living species of the order Hyracoidea, and the only one in the genus Procavia.[1] Rock hyraxes weigh 4–5 kg (8.8–11.0 lb) and have short ears and tails.[3]

| Rock hyrax[1] | |

|---|---|

_2.jpg.webp) | |

| At Erongo, Namibia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Hyracoidea |

| Family: | Procaviidae |

| Genus: | Procavia |

| Species: | P. capensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Procavia capensis (Pallas, 1766) | |

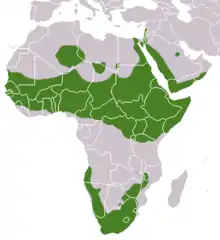

| |

range | |

Rock hyraxes are found at elevations up to 4,200 m (13,800 ft) above sea level[4] in habitats with rock crevices, allowing them to escape from predators.[4][5] They are the only extant terrestrial afrotherians in the Middle East.[note 1] Hyraxes typically live in groups of 10–80 animals, and forage as a group. They have been reported to use sentries to warn of the approach of predators. Having incomplete thermoregulation, they are most active in the morning and evening, although their activity pattern varies substantially with season and climate.

Over most of its range, the rock hyrax is not endangered, and in some areas is considered a minor pest. In Ethiopia, Israel, and Jordan, it is a reservoir of the leishmaniasis parasite.

Along with other hyrax species and the sirenians, this species is the most closely related to the elephant.[6] An unrelated, convergently evolved mammal of similar habits and appearance is the rock cavy of Brazil.

Characteristics

Rock hyraxes are squat and heavily built, with adults reaching a length of 50 cm (20 in) and weighing around 4 kg (8.8 lb), with a slight sexual dimorphism, males being about 10% heavier than females. Their fur is thick and grey-brown, although this varies strongly between different environments, from dark brown in wetter habitats, to light gray in desert-living individuals.[7] Hyrax size (as measured by skull length and humerus diameter) is correlated to precipitation, probably because of the effect on preferred hyrax forage.[8]

Prominent in and apparently unique to hyraxes is the dorsal gland, which excretes an odour used for social communication and territorial marking. The gland is most clearly visible in dominant males.[9]

The rock hyrax has a pointed head, short neck, and rounded ears. It has long, black whiskers on its muzzle.[10] The rock hyrax has a prominent pair of long, pointed tusk-like upper incisors, which are reminiscent of the elephant, to which the hyrax is distantly related. The fore feet are plantigrade, and the hind feet are semidigitigrade. The soles of the feet have large, soft pads that are kept moist with sweat-like secretions. In males, the testes are permanently abdominal, another anatomical feature that hyraxes share with elephants and sirenians.[9]

Thermoregulation in rock hyraxes has been subject to much research, as their body temperature varies with a diurnal rhythm. Animals kept in constant environmental conditions also display such variation,[9] and this internal mechanism may be related to water balance regulation.[11]

Skull of a rock hyrax

Skull of a rock hyrax The dorsal gland visible as a patch of fur with lighter colour

The dorsal gland visible as a patch of fur with lighter colour The characteristic foot pads

The characteristic foot pads The rock hyrax is a stoutly built, rotund animal.

The rock hyrax is a stoutly built, rotund animal. The unusual incisors

The unusual incisors Rock hyrax from Mt Kenya

Rock hyrax from Mt Kenya Dassie near Cape Town

Dassie near Cape Town Rock hyrax

Rock hyrax

Distribution and geographic variation

The rock hyrax occurs widely across sub-Saharan Africa in disjunct northern and southern populations; it is absent from the Congo Basin and Madagascar. The distribution encompasses southern Algeria, Libya, Egypt, and the Middle East, with populations in Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and the Arabian Peninsula.[2] The northern subspecies was introduced to Jebel Hafeet, which is on the border of Oman and the United Arab Emirates.[12]

The shade of their pelts varies individually and regionally.[13] In particular, the dorsal patches (present in both sexes) of the central populations are very variable, ranging from yellow to black, or flecked. In outlying populations, these are more constant in colour, black in P. c. capensis, cream in P. c. welwitschii, and orange in P. c. ruficeps.[13] A larger, longer-haired population is abundant in the moraines in the alpine zone of Mount Kenya.[14][15]

The subspecies, which are sometimes elevated to full species, are:[13]

- P. c. capensis (Pallas, 1766) – Cape rock hyrax, native to South Africa and Namibia

- P. c. habessinicus (Hemprich and Ehrenberg, 1832) – Ethiopian rock hyrax, native to northeastern Africa and Arabia

- P. c. johnstoni Thomas, 1894 – black-necked rock hyrax, native to central and East Africa

- P. c. ruficeps (Hemprich and Ehrenberg, 1832) – red-headed rock hyrax, native to the southern Sahara

- P. c. welwitschii (Gray, 1868) – Kaokoveld rock hyrax, native to the Kaokoveld of Namibia

Ecology and behavior

Rock hyraxes build dwelling holes in any type of rock with suitable cavities, such as sedimentary rocks and soil.[16] In Mount Kenya, rock hyraxes live in colonies comprising an adult male, several adult females, and immatures. They are active during the day, and sometimes during moonlit nights.[17] The dominant male defends and watches over the group. The male also marks his territory.

In Africa, hyraxes are preyed on by leopards, Egyptian cobras, puff adders, rock pythons, caracals, wild dogs, hawks, and owls.[18] Verreaux's eagle in particular is a specialist hunter of hyraxes.[19][20] In Israel, the rock hyrax is reportedly rarely preyed upon by terrestrial predators, as their system of sentries and reliable refuges provide considerable protection. Hyrax remains are almost absent from the droppings of wolves in the Judean Desert.[21]

Feeding and foraging

Hyraxes feed on a wide variety of plant species, including Lobelia[17] and broad-leafed plants.[22] They also have been reported to eat insects and grubs.[10] They forage for food up to about 50 m from their refuge, usually feeding as a group and with one or more acting as sentries from a prominent lookout position. On the approach of danger, the sentries give an alarm call, and the animals quickly retreat to their refuge.[23]

They are able to go for many days without water due to the moisture they obtain through their food, but quickly dehydrate under direct sunlight.[24] Despite their seemingly clumsy build, they are able to climb trees (although not as readily as Heterohyrax), and readily enter residential gardens to feed on the leaves of citrus and other trees.

The rock hyrax also makes a loud, grunting sound while moving its jaws as if chewing, and this behaviour may be a sign of aggression. Some authors have proposed that observation of this behavior by ancient Israelites gave rise to the misconception given in Leviticus 11:4–8 that the hyrax chews the cud,[25] but the hyrax is not a ruminant.[9]

Reproduction

Rock hyraxes give birth to two to four young after a gestation period of 6–7 months (long, for their size). The young are well developed at birth with fully opened eyes and complete pelage. Young can ingest solid food after two weeks and are weaned at 10 weeks. After 16 months, they become sexually mature, they reach adult size at 3 years, and they typically live about 10 years.[9] During seasonal changes, the weight of the male reproductive organs (testes, seminal vesicles) changes due to sexual activity. Between May and January in Cape Province, South Africa, the males are inactive sexually. From February onward, the weight of these organs increases dramatically and the males are able to copulate.[26]

Group structure

Hyraxes that live in more "egalitarian" groups, in which social associations are spread more evenly among group members, survive longer.[27] In addition, hyraxes are the first nonhuman species in which structural balance was described. They follow "the friend of my friend is my friend" rule, and avoid unbalanced social configurations.[28] The balance of social interactions within a group is positively correlated to individual longevity, meaning that "it is not the number or strength of associations that an adult individual has (i.e. centrality) that is important, but the overall configuration of social relationships within the group."[29] The reason for such a balanced group configuration, rather than one that is centrally dominated by a few individual hyraxes, was suggested to have to do with the fact that information flow to all members is important in a fragmented habitat as that of the hyrax, making a dominance hierarchy a liability for the survival of the group at large.[29]

Vocalisations

Captive rock hyraxes make more than 20 different noises and vocal signals.[17] The most familiar one is a high trill, given in response to perceived danger.[10] Rock hyrax calls can provide important biological information, such as size, age, social status, body weight, condition, and hormonal state of the caller, as determined by measuring their call length, patterns, complexity, and frequency.[30] More recently, researchers have found rich syntactic structure and geographical variations in the calls of rock hyraxes, a first in the vocalization of mammalian taxa other than primates, cetaceans, and bats.[31] Higher-ranked males tend to sing more often, and the energetic cost of singing is relatively low.[32] A recent study found that snorts, a rare aspect of male hyrax songs, play an important signalling role as well, with increasing snort harshness being associated with "the progression of inner excitement or aggression". It is also positively associated with the singing animal's social status and testosterone levels.[33] Singing has also been shown to be a marker of an individual hyrax's unique identity, where identity is expressed by unique vocal signatures "that are not condition dependent and are stable over years in singers that did not alter their spatial position."[34]

Resting

The rock hyrax spends roughly 95% of its time resting.[9] During this time, it can often be seen basking in the sun, which sometimes involves "heaping", where several animals pile on top of each other. This is thought to be an element of its complex thermoregulation.[35]

Dispersal

Male hyraxes have been categorised into four classes: territorial, peripheral, early dispersers, and late dispersers. The territorial males are dominant. Peripheral males are more solitary and sometimes take over a group when the dominant male is missing. Early-dispersing males are juveniles that leave the birth site around 16 to 24 months of age. Late dispersers are also juvenile males, but they leave the birth site much later, around 30 or more months of age.[36]

Names

The species is known as klipdas in Afrikaans (etymology: cliff + badger), while most people just call them "dassies" (the plural of dassie) or "rock rabbits" in South Africa. The Swahili names for them are pimbi, pelele, and wibari, though the latter two names are nowadays reserved for the tree hyraxes.[37] This species has many subspecies, many of which are also known as rock or Cape hyrax, although the former usually refers to African varieties.

In Arabic, the rock hyrax is called الوبر الصخري (Alwabr alsakhri) or طبسون (tabsoun). In Hebrew, the rock hyrax is called שפן סלע (shafan sela), meaning rock shafan, where the meaning of shafan is obscure, but is colloquially used as a synonym for rabbit in modern Hebrew.[25] According to Gerald Durrell, local people in Bafut, Cameroon, call the rock hyrax the n'eer.[38]

Naturopathic use

Rock hyraxes produce large quantities of hyraceum, a sticky mass of dung and urine that has been employed as a South African folk remedy in the treatment of several medical disorders, including epilepsy and convulsions.[39] Hyraceum is now being used by perfumers, who tincture it in alcohol to yield a natural animal musk.[40]

In culture

The rock hyrax is classified as treif (not kosher; unclean) according to kashrut – Jewish food hygiene rules – due to statements in the Old Testament in Leviticus 11:5: "And the coney, because he cheweth the cud, but divideth not the hoof; he is unclean unto you".[41] Hyraxes are also mentioned in Proverbs 30:26 as one of a number of remarkable animals for being small but exceedingly wise, in this case because "the conies are a people not mighty, yet they make their homes in the cliffs".[42]

In Joy Adamson's books and the film Born Free, a rock hyrax called Pati-Pati was her companion for six years before Elsa and her siblings came along; Pati-Pati reportedly took the role of nanny and watched over them with great care.[43]

The 2013 animated film Khumba features a number of rock hyraxes that sacrifice one of their own to a white Verreaux's eagle.

Gallery

Rock hyrax can reach a length of 50 cm (20 in) and weigh around 4 kg (8.8 lb).

Rock hyrax can reach a length of 50 cm (20 in) and weigh around 4 kg (8.8 lb). Basking on Table Mountain, South Africa

Basking on Table Mountain, South Africa Klipdassie in Betty's Bay Betty's_Bay, South Africa

Klipdassie in Betty's Bay Betty's_Bay, South Africa A colony of hyraxes in northern Israel

A colony of hyraxes in northern Israel Rock hyrax in the botanical garden of Pretoria, South Africa

Rock hyrax in the botanical garden of Pretoria, South Africa Collar-tagged rock hyrax, Ein Gedi, Israel

Collar-tagged rock hyrax, Ein Gedi, Israel Animated skull, Namibia

Animated skull, Namibia Rock hyrax, Katzrin, Golan Heights

Rock hyrax, Katzrin, Golan Heights Rock hyrax, running, Ein Gedi

Rock hyrax, running, Ein Gedi Rock hyrax (dassie) at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa

Rock hyrax (dassie) at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa%252C_South_Africa.jpg.webp) Dassie with young in Hermanus, South Africa

Dassie with young in Hermanus, South Africa Rock hyrax showing incisors and tongue, at Ein Gedi, Israel

Rock hyrax showing incisors and tongue, at Ein Gedi, Israel

See also

Mammals portal

Mammals portal

Notes

- The marine dugong is also present in the area.

References

- Shoshani, J. (2005). "Order Hyracoidea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Butynski, T.; Hoeck, H.; Koren, L. & de Jong, Y.A. (2015). "Procavia capensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T41766A21285876. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T41766A21285876.en. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- "Hyrax". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- George A. Feldhamer; Lee C. Drickamer; Stephen H. Vessey; Joseph F. Merritt; Carey Krajewski (2007). Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, Ecology. JHU Press. p. 376. ISBN 9780801886959.

- Adrienne Gear (2008). Nonfiction Reading Power: Teaching Students how to Think While They Read All Kinds of Information. Pembroke Publishers Limited. p. 105. ISBN 9781551382296.

- Jane B. Reece; Noel Meyers; Lisa A. Urry; Michael L. Cain; Steven A. Wasserman; Peter V. Minorsky (2015). Campbell Biology Australian and New Zealand Edition. Pearson Higher Education AU. p. 470. ISBN 9781486012299.

- Bothma, J.d.P. (1966). "Color Variation in Hyracoidea from Southern Africa". Journal of Mammalogy. 47 (4): 687–693. doi:10.2307/1377897. JSTOR 1377897.

- Klein, R.G.; CruzUribe (1996). "Size variation in the rock hyrax (Procavia capensis) and late Quaternary climatic change in South Africa". Quaternary Research. 46 (2): 193–207. Bibcode:1996QuRes..46..193K. doi:10.1006/qres.1996.0059. S2CID 140669754.

- Olds, N.; Shoshani, J. (1982). "Procavia capensis" (PDF). Mammalian Species (171): 1–7. doi:10.2307/3503802. JSTOR 3503802. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-10-30.

- "The Living Desert - Rock Hyrax". Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- Meltzer, A. (1973) Heat balance and water economy of the rock hyrax (Procavia capensis syriaca Schreber 1784). Unpubl. Ph.D. dissert., Tel-Aviv Univ., Israel, 135 pp.

- Edmonds, J.-A.; Budd, K. J.; Al Midfa, A. & Gross, C. (2006). "Status of the Arabian Leopard in United Arab Emirates" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 1): 33–39.

- Kingdon, Jonathan (2015). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals (2 ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 296–297. ISBN 9781472921352.

- Coe, Malcolm James. (1967). The ecology of the Alpine zone of Mount Kenya. Dr. W. Junk. OCLC 559542.

- Lonely Planet Publications (Firm), issuing body. (June 2018). Kenya. ISBN 9781787019003. OCLC 1046678247.

- Sale, J. B. (1966). "The habitat of the rock hyrax". Journal of the East African Natural History Society. 25: 205–214.

- Young, T. P., & Matthew, R. E. (1993). Alpine vertebrates of Mount Kenya, with particular notes on the rock hyrax. East Africa Natural History Society.

- Turner, M. I. M.; Watson, R. M. (1965). "An introductory study on the ecology of hyrax (Dendrohyrax brucei and Procavia johnstoni) in the Serengeti National Park". African Journal of Ecology. 3: 49–60. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1965.tb00737.x.

- Estes, R. D. (1999). The Safari Companion. Chelsea Green Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-890132-44-6.

- Unwin, M. (2003). Southern African Wildlife. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-060-2.

- Margolis, E. (2008). "Dietary composition of the wolf Canis lupus in the Ein Gedi area according to analysis of their droppings (in Hebrew)". Proceedings of the 45th Meeting of the Israel Zoological Society.

- "Nature Niche-The Rock Hyrax(Procavia capensis)". Archived from the original on 2009-03-24. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- Kotler, B. P.; Brown, J. S.; Knight, M. H. (1999). "Habitat and patch use by hyraxes: there's no place like home?". Ecology Letters. 2 (2): 82–88. doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.1999.22053.x.

- African Wildlife Foundation: Hyrax

- Slifkin, N. (2004). "Shafan — The Hyrax" (PDF). The camel, the hare & the hyrax: a study of the laws of animals with one kosher sign in light of modern zoology. Southfield, MI; Nanuet, NY: Zoo Torah in association with Targum, Feldheim. pp. 99–135. ISBN 978-1-56871-312-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-06-16.

- Glover, T.D.; Millar, R.P. (1970). "Seasonal Changes in the Reproductive Tract of the Male Rock Hyrax". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 23 (3): 497–499. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0230496.

- Barocas, A.; Ilany, A.; Koren, L.; Kam, M.; Geffen, E. (2011). "Variance in Centrality within Rock Hyrax Social Networks Predicts Adult Longevity". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e22375. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622375B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022375. PMC 3144894. PMID 21818314.

- Ilany, A.; Barocas, A.; Koren, L.; Kam, M.; Geffen, E. (2013). "Structural balance in the social networks of a wild mammal". Animal Behaviour. 85 (6): 1397–1405. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.03.032. S2CID 28628927.

- Barocas, Adi; Ilany, Amiyaal; Koren, Lee; Kam, Michael; Geffen, Eli (2011-07-27). "Variance in Centrality within Rock Hyrax Social Networks Predicts Adult Longevity". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e22375. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622375B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022375. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3144894. PMID 21818314.

- Koren, L.; Geffen, E. (2009). "Complex call in male rock hyrax (Procavia capensis): a multi-information distributing channel". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 63 (4): 581–590. doi:10.1007/s00265-008-0693-2. S2CID 23659460.

- Kershenbaum, A.; Ilany, A.; Blaustein, L.; Geffen E. (2012). "Syntactic structure and geographical dialects in the songs of male rock hyraxes". Proceedings of the Royal Society. B (1740): 1–8. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0322. PMC 3385477. PMID 22513862.

- Ilany, A.; Barocas, A.; Kam, M.; Ilany, T.; Geffen, E. (2013). "The energy cost of singing in wild rock hyrax males: evidence for an index signal". Animal Behaviour. 85 (5): 995–1001. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.02.023. S2CID 43767291.

- Weissman, Yishai A.; Demartsev, Vlad; Ilany, Amiyaal; Barocas, Adi; Bar-Ziv, Einat; Koren, Lee; Geffen, Eli (2020-08-01). "A crescendo in the inner structure of snorts: a reflection of increasing arousal in rock hyrax songs?". Animal Behaviour. 166: 163–170. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2020.06.010. ISSN 0003-3472. S2CID 220499081.

- Koren, Lee; Geffen, Eli (2011-04-01). "Individual identity is communicated through multiple pathways in male rock hyrax (Procavia capensis) songs". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 65 (4): 675–684. doi:10.1007/s00265-010-1069-y. ISSN 1432-0762. S2CID 40657166.

- "The Creature Feature: 10 Fun Facts About the Rock Hyrax (Or, Are You Ready to Rock Hyrax?)". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- "Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens: Things to See and do". Archived from the original on 2009-07-09. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Durrell, G. (1954). The Bafut Beagles. Rupert Hart-Davies.

- Olsen, A., Prinsloo, L. C., Scott, L., Jägera, A, K. (2008) "Hyraceum, the fossilized metabolic product of rock hyraxes (Procavia capensis), shows GABA-benzodiazepine receptor affinity". South African Journal of Science 103.

- Profumo, Dominique Dubrana aka AbdesSalaam Attar for La Via del. "Hyraceum - Perfumetherapy - Procavia Capensis - 100% Natural Perfumes Made in Italy". www.profumo.it. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- Leviticus 11:4–5; Deuteronomy 14:7

- Prov 30:26, KJB

- Adamson, J. (1961). Elsa – The Story Of A Lioness, London: Collins & Harvill Press. P. 3.

External links

- Animal Diversity : Procavia capensis

- View the hyrax genome on Ensembl

- Cute dassie on Table Mountain

- View the proCap1 genome assembly in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- More information and photos of rock hyraxes in Mt Kenya

.jpg.webp)